Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition (2014)

Part V. Appendixes

Appendix B. Troubleshooting

Whether it’s a car engine or an operating system, anything with several thousand parts can develop the occasional technical hiccup. OS X is far more resilient than its predecessors, but it’s still a complex system with the potential for occasional glitches.

Most freaky little glitches go away if you just try these two steps, one at a time:

§ Quit and restart the wayward program.

§ Log out and log back in again.

It’s the other problems that’ll drive you batty.

Minor Eccentric Behavior

All kinds of glitches may befall you, occasionally, in OS X. A menu doesn’t open when you click it. A program doesn’t open—it just bounces in the Dock a couple of times and then stops. A program freezes.

When a single program is acting up like this, but quitting and restarting it does no good, try the following steps, in the following sequence.

First Resort: Repair Permissions

An amazing number of mysterious glitches arise because the permissions of either that item or something in your System folder—that is, the complex mesh of interconnected Unix permissions—have become muddled.

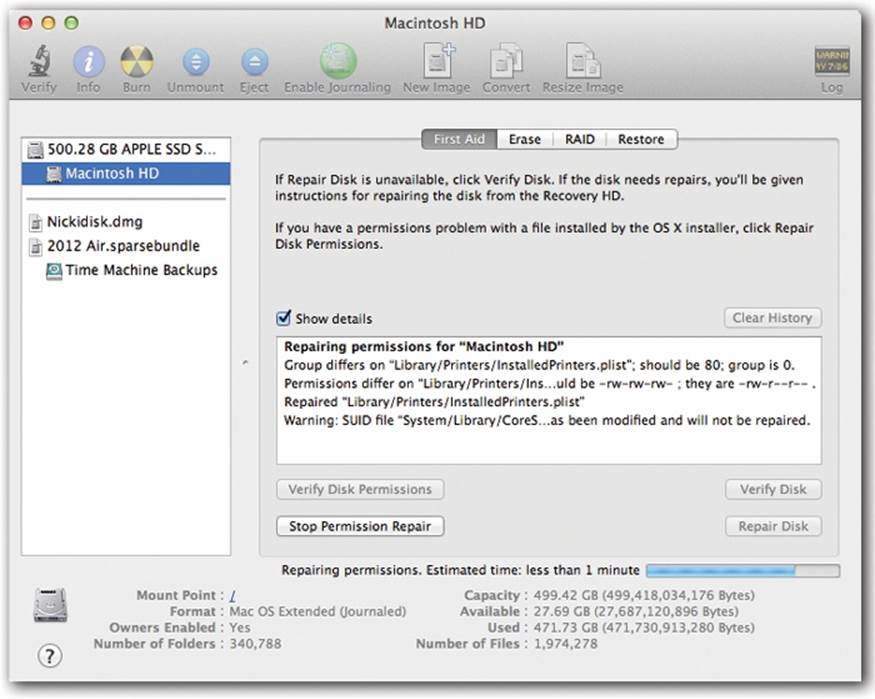

When something doesn’t seem to be working right, therefore, open your Applications→Utilities folder and open Disk Utility. Proceed as shown in Figure B-1.

This is a really, really great trick to know.

Figure B-1. Click your hard drive’s name in the left-side list, click the First Aid tab, click Repair Disk Permissions, and then read an article while the Mac checks out your disk. If the program finds anything amiss, you’ll see messages like these. Among the text, you may recognize some Unix shorthand for read, write, and execute privileges.

Second Resort: Look for an Update

If a program starts acting up immediately after you’ve installed OS X 10.9, chances are good that it has some minor incompatibility. Chances are also good that you’ll find an updated version on the company’s Web site.

Third Resort: Toss the Prefs File

A corrupted preference file can bewilder the program that depends on it.

Before you go on a dumpfest, however, take this simple test: Log in using a different account (perhaps a dummy account that you create just for testing purposes). Run the problem program. Is the problem gone? If so, then the glitch exists only when you are logged in—which means it’s a problem with your copy of the program’s preferences.

Return to your own account. Open your Home→Library→Preferences folder, where you’ll find neatly labeled preference files for all the programs you use. (To open the hidden Library folder, press the Option key as you open the Go menu; choose Library.)

Each preference file ends with the file name suffix .plist. For example, com.apple.finder.plist is the Finder’s preference file, com.apple.dock.plist is the Dock’s, and so on.

Put the suspect preference file into the Trash, but don’t empty it. The next time you run the recalcitrant program, it will build itself a brand-new preference file that, if you’re lucky, lacks whatever corruption was causing your problems.

If not, quit the program. You can reinstate its original .plist file from the Trash, if you find that helpful as you pursue your troubleshooting agenda.

Remember, however, that you actually have two Preferences folders. In addition to your own Home folder’s stash, there’s a second one in the Library folder in the main hard drive window (which administrators are allowed to trash; this one contains system-wide preferences, like your network configuration).

In any case, the next time you open the sick program or log in, the Mac creates fresh, virginal preference files.

Fourth Resort: Restart

Sometimes you can give OS X or its programs a swift kick by restarting the Mac. It’s an inconvenient step, but not nearly as time-consuming as what comes next. And it can fix problems that cropped up when you started up the computer.

Last Resort: Trash and Reinstall the Program

Sometimes reinstalling the problem program clears up whatever the glitch was.

First, however, throw away all traces of it. Open the Applications folder and drag the program’s icon (or its folder) to the Trash. In most cases, the only remaining pieces to discard are its .plist file (or files) in your Home→Library→Preferences folder, and any scraps bearing the program’s name in your Library→Application Support folder. (You can do a quick Spotlight search to round up any other pieces.)

Then reinstall the program from its original disc or installer—after first checking the company’s Web site to see if there’s an updated version, of course.

Frozen Programs (Force Quitting)

The occasional unresponsive application has become such a part of OS X life that, among the Mac cognoscenti online, the dreaded, endless “please wait” cursor has been given its own acronym: SBOD (Spinning Beachball of Death). When the SBOD strikes, no amount of mouse clicking and keyboard pounding will get you out of the recalcitrant program.

Here are the different ways you can go about force quitting a stuck program (the equivalent of pressing Ctrl-Alt-Delete in Windows), in increasing order of desperation:

§ Force quit the usual way. Choose ![]() →Force Quit to terminate the stuck program, or use one of the other force-quit methods described on Force Quitting Programs.

→Force Quit to terminate the stuck program, or use one of the other force-quit methods described on Force Quitting Programs.

§ Force quit the sneaky way. Some programs, including the Dock, don’t show up at all in the usual Force Quit dialog box. Your next attempt, therefore, should be to open the Activity Monitor program (in Applications→Utilities), which shows everything that’s running. Double-click a program and then, in the resulting dialog box, click Quit to force quit it. (Unix hounds: You can also use the kill command in Terminal.)

§ Force quit remotely. If the Finder itself has locked up, you can’t very well get to Activity Monitor (unless it occurred to you beforehand to stash its icon in your Dock—not a bad idea). At this point, you may have to abort the locked program from another computer across the network, if you’re on one, by using the SSH (secure shell) command.

TIP

If all of this seems like a lot to remember, you can always force restart the Mac. On most Macs, you do that by holding down the power button for 5 seconds. If that doesn’t work, press Control-⌘-power button.

Recovery Mode: Three Emergency Disks

OS X, as you’ve probably heard, no longer comes on a DVD. When your Mac won’t even start up, there’s no DVD to insert as a backup startup disk, as there always was before. That’s a scary place to be; if your hard drive is sick, then everything on it may be inaccessible to you. What you need is an emergency drive that can repair the hard drive and get you back in operation.

Apple is way ahead of you on this one. It offers three simulated repair disks: three ways to supply disk-repair and system software–repair tools in times of crisis.

The Recovery HD

Here’s the sneaky surprise: When you install Mavericks, it automatically creates an invisible hidden “hard drive” (a partition of your main drive that has its own icon) called Recovery HD. It’s a 650-megabyte “drive” that’s generally invisible to you. It’s even invisible to Disk Utility, so even if you erase your hard drive, the Recovery HD is still there to help you.

But if you can’t seem to start up your Mac properly, or if your hard drive is acting a little flaky, you’ll be glad you had this “separate” startup disk. On it, Apple has provided some emergency tools for fixing drive or software glitches, restoring files, browsing the Web, and even reinstalling OS X.

NOTE

The OS X installer creates the Recovery HD partition only if your startup drive is an internal drive. In certain other situations, it won’t create the partition—for example, if you’re installing OS X onto a RAID volume or one with a non-standard Boot Camp partition setup.

You can power up your Mac from the Recovery HD in either of two ways:

§ Hold down ⌘-R as the Mac is starting up. You can let go when you see the Apple logo appear.

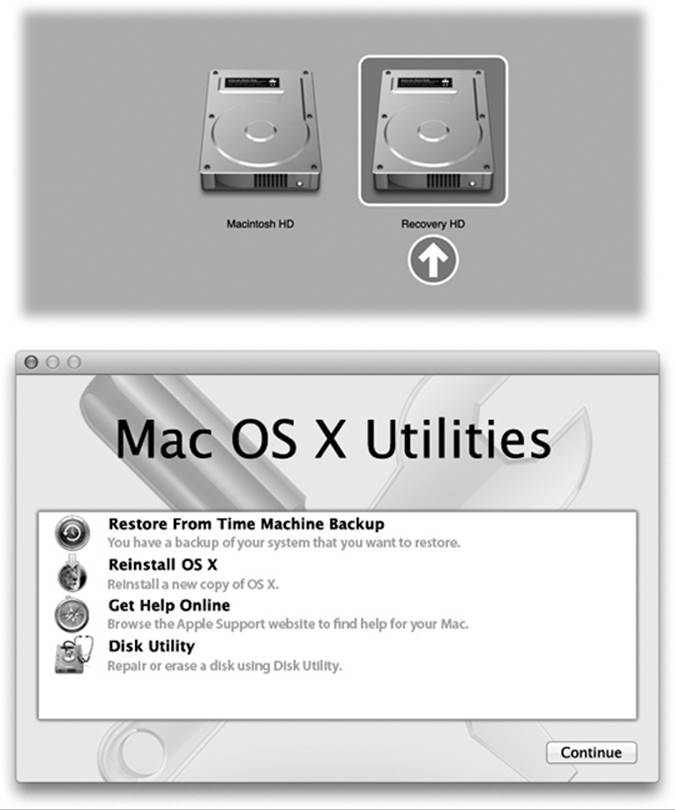

§ Hold down the Option key as the Mac is starting up. When you see the Startup Manager (Figure B-2, top), let go. Click the up-arrow button below the Recovery HD icon.

Either way, you wind up at the Utilities screen shown in Figure B-2, bottom.

Here, Apple has supplied you with four important tools:

§ Restore From Time Machine Backup. If your Mac is really hosed, this is the option you want. It restores your entire software world—programs, data, settings, OS X itself—from the Time Machine backup you carefully set up as you read Chapter 5.

Figure B-2. Top: This simple display of disk icons is known as the Startup Manager. It’s an easy way to specify which disk you want to start up from. Bottom: Here’s the point of the Recovery HD partition: a screen full of emergency utilities that can fix your Mac’s regularly scheduled hard drive. If there’s a pop-up menu at the bottom, it’s for choosing a WiFi hotspot so that you can access the rest of your network. That might be useful when, for example, you want to access your Time Machine backups.

This option completely erases your existing hard drive, so—you know. Be sure.

Once you choose this option, click Continue. You’re now asked to choose the Time Machine drive, then the time-stamped backup you want to restore from, and, finally, the drive or partition you want to wipe out. You get one more warning that you’re about to wipe out the destination drive. When you click Continue, the restoration begins. When it’s all over—usually a couple of hours later—the Mac restarts as though nothing ever happened.

§ Reinstall OS X. You can use this option to install a copy of OS X onto any hard drive—for example, you could reinstall it on your main internal drive.

NOTE

This option will download the actual copy of Mavericks from the Internet—all 5.3 gigabytes of it. In other words, it requires an Internet connection and a lot of patience.

§ Get Help Online. This option opens your Safari Web browser, which presents you with some helpful information about using the Recovery Mode that you’ve fired up. You’re actually online at this point, so you can also visit any other Web site you might find helpful.

Quit Safari when you’re finished browsing; you return to the main OS X Utilities window.

§ Disk Utility. Use this option to open Disk Utility, the Mac’s hard drive diagnostics-and-repair program. You can use it to check, fix, erase, or partition any of your hard drives.

For example, you can repair the main startup disk, which is often the most useful option.

Those four options are the big-ticket items, but don’t miss the menu bar. The commands here let you open the Firmware Password Utility, Network Utility (Network Utility), and Terminal (Saving a report).

Mavericks Internet Recovery

OK, the Recovery HD concept is clever. And most of the time, it’s all you need.

But what if your hard drive is completely hosed? What then, smart guy? You can’t very well boot up from the Recovery HD if it’s sitting on the same dead hard drive.

Or what if you’ve just installed a brand-new, bigger, or faster hard drive? It doesn’t have OS X on it. It doesn’t have Recovery HD on it. How are you supposed to install Mavericks?

In those situations, recent Mac models—those released in 2011 and later—offer an even cleverer option: Internet Recovery. This mode offers the same exact options that the Utilities screen of Recovery HD would have—but you’re connecting to that software online, over a high-speed Internet connection. You’re literally starting up from Apple’s hard drives, thousands of miles away.

So even if your hard drive is dead as a doornail, you can still repair it, reinstall OS X, and so on.

To fire up Internet Recovery, make sure your computer is in a WiFi hotspot or connected to an Ethernet network. Then hold down ⌘-R as the computer is starting up. You can let go when you see the screen that asks you to choose a WiFi network. Do that, and then enter the password for the network, if necessary.

Now your Mac downloads a disk image containing just enough software to get you to the Utilities screen described in the previous section.

NOTE

Once you’re up and running, you can re-download the copies of iPhoto, iMovie, and GarageBand that came with your Mac. Just open the App Store program, log in with your Apple ID, click Purchases, and click Accept to download those iLife programs. You won’t be charged for them.

Physical Recovery Disks

But what if the hard drive is so sick that you can’t start up from the Recovery HD—and your Mac isn’t new enough to offer the Internet Recovery feature? (Or what if it does offer that feature, but you’d rather repair your Mac a quicker way?)

One solution is to build yourself a bootable OS X flash drive, DVD, or hard drive, as described on Recovery Mode: Three Emergency Disks. Not only is it capable of starting up or reinstalling OS X, but it also has a complete set of recovery tools on board.

But creating a bootable drive takes a lot of steps, and it requires sacrificing an 8-gigabyte (or bigger) flash drive. If you have any flash drive, even a 2-gigabyte one that somebody handed you at a trade show, you can load it up with just the recovery tools, to use in times of trouble. Creating this kind of emergency flash drive is somewhat easier than creating the kind of full-blown reinstallation flash drive described in Appendix A.

NOTE

To create an emergency “disk,” your Mac must have OS X on it already, including the invisible Recovery HD partition. That’s because it relies on the data and software on that partition.

Also, you have to format the flash drive correctly, as described on The Homemade Installer Disk. It’s OK if the flash drive is partitioned; just leave at least 2 gigs for the recovery partition.

To get started, download Apple’s free OS X Recovery Disk Assistant. (It’s available from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com. It may seem to be intended for Mountain Lion, but it still works fine in Mavericks.)

Insert your flash drive into the Mac. Open the OS X Recovery Disk Assistant; click Agree to get through the legalese screen.

Click the name of the flash drive, and then click Continue. You’re warned that this process will erase the flash drive (or its partition), and you’re asked to authenticate yourself with an administrator name and password.

When you click OK, your Mac begins creating the recovery disk. After a minute or so, a message congratulates you, and the newly created drive’s icon appears in the Recovery Disk Assistant program, bearing the name Recovery HD.

To use this emergency disk, hold down the Option key as the Mac starts up. You wind up at the Startup Manager screen shown in Figure B-2, top. From the pop-up menu, choose your WiFi hotspot.

Now click the up-arrow button below the Recovery HD icon. (You may even see two Recovery HD icons—one of them is the USB flash drive, and the other is the invisible partition on your hard drive.) Your Mac is starting up from the flash drive! After a moment, you wind up at the Utilities screen described earlier in this appendix.

NOTE

The recovery flash drive you made will work only on the Mac model you used to make it.

Application Won’t Open

If a program won’t open (if its icon bounces merrily in the Dock for a few seconds, for instance, but then nothing happens), begin by trashing its preference file, as described earlier. If that doesn’t solve it, reinstalling the program, or installing the Mavericks–compatible update for it, usually does.

Startup Problems

Not every problem you encounter is related to running applications. Sometimes trouble strikes before you even get that far. The following are examples.

Kernel Panic

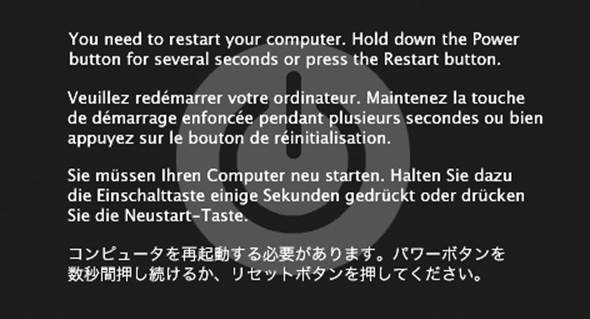

When you see the cheerful, multilingual dialog box shown in Figure B-3 you’ve got yourself a kernel panic—a Unix nervous breakdown.

Figure B-3. A kernel panic is almost always related to some piece of add-on hardware. And look at the bright side: At least you get this handsome dialog box. That’s a lot better than the Mac OS X 10.0 and 10.1 effect: random text gibberish superimposing itself on your screen.

(In such situations, user panic might be the more applicable term, but that’s programmers for you.)

If you experience a kernel panic, it’s almost always the result of a hardware glitch—most often a bad memory (RAM) board, but possibly an accelerator card, graphics card, or USB hub that OS X doesn’t like. A poorly seated AirPort card can bring on a kernel panic, too, and so can a bad USB or FireWire cable.

If simply restarting the machine doesn’t help, detach every shred of gear that didn’t come from Apple. Restore these components to the Mac one at a time until you find out which one was causing OS X’s bad hair day. If you’re able to pinpoint the culprit, seek its manufacturer (or its Web site) on a quest for updated drivers, or at least try to find out for sure whether the add-on is compatible with OS X.

TIP

This advice goes for your Macintosh itself. Apple periodically updates the Mac’s own “drivers” in the form of a firmware update. You download these updates from the Support area of Apple’s Web site (if indeed OS X’s own Software Update mechanism doesn’t alert you to their existence).

There’s one other cause for kernel panics, by the way, and that’s moving, renaming, or changing the access permissions for OS X’s essential system files and folders—the Applications or System folder, for example. (See Chapter 15 for more on permissions.) This cause isn’t even worth mentioning, of course, because nobody would be that foolish.

Safe Mode (Safe Boot)

In times of troubleshooting, Windows fans press an F-key to start up in Safe Mode. That’s how you turn off all nonessential system-software nubbins in an effort to get a sick machine at least powered up.

Although not one person in a hundred knows it, OS X offers the same kind of emergency keystroke. It can come in handy when you’ve just installed some new piece of software and find that you can’t even start up the machine, or when one of your fonts is corrupted, or when something you’ve designated as a login item turns out to be gumming up the works. With this trick, you can at least turn on the computer so that you can uninstall the cranky program.

The trick is to press the Shift key as the machine is starting up. Hold it down from the startup chime until you see the words “Safe Boot,” in red lettering, on the login screen.

Welcome to Safe Mode.

What have you accomplished?

§ Checked your hard drive. The Shift-key business makes the startup process seem to take a very long time; as the progress bar suggests, OS X is actually scanning your entire hard drive for problems.

§ Brought up the login screen. When you do a safe boot, you must click your name and enter your password, even if you normally have Automatic Login turned on.

§ Turned off noncritical kernel extensions (drivers). All kinds of software nuggets load during the startup process. Some of them you choose yourself, like icons you add to the Login Items list in the System Preferences→Accounts pane. Others are normally hidden, including a large mass of kernel extensions, which are chunks of software that add various features to the basic operating system. (Kernel extensions live in your System→Library→Extensions folder.)

If you’re experiencing startup crashes, some non-Apple installer may have given you a kernel extension that doesn’t care for OS X 10.9—so in Safe Mode, they’re all turned off.

§ Turned off your fonts. Corrupted fonts are a chronic source of trouble—and because you can’t tell by looking, they’re darned difficult to diagnose. So just to make sure you can at least get into your computer, Safe Mode turns them all off (except the authorized, Apple-sanctioned ones that it actually needs to run, which are in your System→Library→Fonts folder).

§ Trashed your font cache. The font cache is a speed trick. OS X stores the visual information for each of your fonts on the hard drive so the system won’t have to read every single typeface off your hard drive when you open your Font menus or the Font panel.

When these files get scrambled, startup crashes can result. That’s why a Safe Boot moves all these files into the Trash. (You’ll even see them sitting there in the Trash after the startup process is complete, although there’s not much you can do with them except walk around holding your nose and pointing.)

§ Turned off your login items. Safe Mode also prevents any Finder windows from opening and prevents your own handpicked startup items from opening—that is, whatever you’ve asked your Mac to auto-open by adding them to the System Preferences→Accounts→Login Items list.

This, too, is a troubleshooting tactic. If some login item crashes your Mac every time it opens, you can squelch it just long enough to remove it from your Login Items list.

TIP

If you don’t hold down the Shift key until you click the Log In button (after entering your name and password at the login screen), you squelch only your login items but not the fonts and extensions.

Once you reach the desktop, you’ll find a long list of standard features inoperable. You can’t use DVD Player, capture video in iMovie, use a wireless network, or use certain microphones and speakers. (The next time you restart, all this goodness will be restored, assuming you’re no longer clutching the Shift key in a sweaty panic.)

In any case, the beauty of Safe Mode is that it lets you get your Mac going. You have access to your files, so at least the emergency of crashing-on-startup is over. And you can start picking through your fonts and login items to see if you can spot the problem.

Gray Screen During Startup

Confirm that your Mac has the latest firmware, as described earlier. Detach and test all your non-Apple add-ons. Finally, perform a disk check (see below).

Blue Screen During Startup

Most of the troubleshooting steps for this problem (which is usually accompanied by the Spinning Beachball of Death cursor) are the same as those described under Kernel Panic.

Forgotten Password

If you or one of the other people who use your Mac have forgotten the corresponding account password, no worries: Just read the box on The Forgotten-Password Survival Guide.

Fixing the Disk

The beauty of OS X’s design is that the operating system itself is frozen in its perfect, pristine state, impervious to conflicting system extensions, clueless Mac users, and other sources of disaster.

That’s the theory, anyway. But what happens if something goes wrong with the complex software that operates the hard drive itself?

Fortunately, OS X comes with its own disk-repair program. In the familiar Mac universe of icons and menus, it takes the form of a program in Applications→Utilities called Disk Utility. In the barren world of Terminal and the command-line interface, there’s a utility that works just as well but bears a different name: fsck (for file system check).

In any case, running Disk Utility or its alter ego fsck is a powerful and useful troubleshooting tool that can cure all kinds of strange ills, including these problems, among others:

§ Your Mac freezes during startup, either before or after the login screen.

§ The startup process interrupts itself with the appearance of the text-only command line.

§ You get the “applications showing up as folders” problem.

Method 1: Disk Utility

The easiest way to check your disk is to use the Disk Utility program. Use this method if your Mac can, indeed, start up. (See Method 2 if you can’t even get that far.)

Disk Utility can’t fix the disk it’s on (except for permissions repairs, described at the beginning of this appendix). That’s why you have to restart the Mac into Recovery Mode and run Disk Utility from there. The process goes like this:

1. Start up the Mac from the Recovery HD, or a recovery flash drive.

They’re both described earlier in this appendix. You wind up, after some time, at the Utilities screen.

2. Click “Disk Utility: Repair or erase a disk using Disk Utility.”

After a moment, the Disk Utility screen appears.

3. Click the disk or disk partition you want to fix, click the First Aid tab, and then click Repair Disk.

The Mac whirls into action, checking a list of very technical disk-formatting parameters.

If you see the message, “The volume ‘Macintosh HD’ appears to be OK,” that’s meant to be good news. Believe it or not, that cautious statement is as definitive an affirmation as Disk Utility is capable of making about the health of your disk.

Disk Utility may also tell you that the disk is damaged but that it can’t help you. In that case, you need a more heavy-duty disk-repair program like DiskWarrior (www.alsoft.com).

Method 2: fsck at the Console

Techier folk can also boot into the Mac’s raw Unix underlayer to perform some diagnostic (and healing) commands.

Specifically, you can run the Unix program fsck, for which Disk Utility is little more than a pretty faceplate.

NOTE

Even so, Apple recommends that you use Disk Utility if at all possible. Use fsck only if all else fails.

Like any Unix program, fsck runs at the command line. You launch it from the all-text, black Unix screen by typing fsck and pressing Return. (You can also use fsck -f.)

You can’t, however, just run fsck in Terminal. You have to run it when the usual arsenal of graphic-interface programs—like the Finder and its invisible suite of accessory programs—isn’t running.

Single-user mode (⌘-S at startup)

The Terminal program is the best-known form of OS X’s command line, but it’s not the only one. In fact, there are several other ways to get there.

In general, you don’t hear them mentioned except in the context of troubleshooting, because the Terminal program offers many more convenient features for doing the same thing. And because it’s contained in a OS X–style window, Terminal is not as disorienting as the three methods you’re about to read.

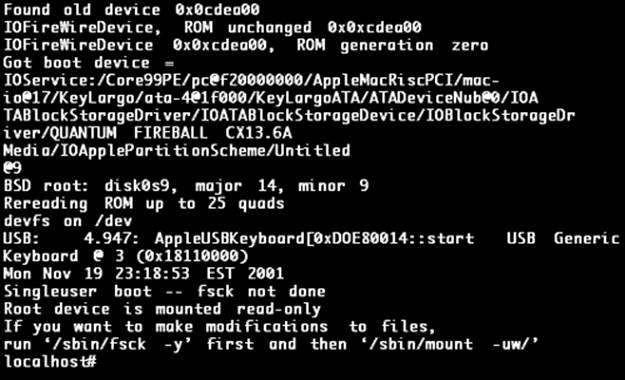

All these techniques take you into console mode, shown in Figure B-4. In console mode, Unix takes over your screen completely, showing white type against black, no windows or icons in sight. Abandon the mouse, all ye who enter here; in console mode, you can’t do anything but type commands.

To get there in times of startup troubleshooting, press ⌘-S while the Mac is starting up. (If you’re stuck at the frozen remnants of a previous startup attempt, you may first have to force restart your Mac; hold down the ![]() button for 5 seconds.)

button for 5 seconds.)

Instead of arriving at the usual desktop, you see technical-looking text scrolling up a black screen as the Mac runs its various startup routines. When it finally stops at the localhost# prompt, you’re ready to type commands. You’re now in what’s called single-user mode, meaning that the Unix multiple-accounts software has yet to load. You won’t be asked to log in.

At the root# prompt, type fsck -y (note the space before the hyphen) and press Return. (The y means “yes,” as in “yes, I want you to fix any problems automatically.”)

Now the file-system check program takes over, running through five sets of tests. When it’s complete, you’ll see one of two messages:

§ The volume Macintosh HD appears to be OK. All is well. Type exit and press Return to proceed to the usual login screen and desktop.

§ File system was modified. A good sign, but just a beginning. You need to run the program again. One fsck pass often repairs only one layer of problems, leaving another to be patched in the next pass. Type fsck -y a second time, a third time, and so on, until you finally arrive at a “disk appears to be OK” message.

Type exit at the prompt and press Return to get back to the familiar world of icons and windows.

Figure B-4. In console mode, your entire screen is a command line interface. Unix jockeys can go to town here. Everyone else can timidly type fsck -y after the localhost:/root # prompt—see this prompt on the very last line?—and hope for the best.

Where to Get Troubleshooting Help

If the basic steps described in this appendix haven’t helped, the universe is crawling with additional help sources. The Apple’s Support Web site is a great resource. But the truth is, you’ll find more answers faster using Google than you ever will using individual help sites. That’s because Google includes all those help sites in its search!

Suppose, for example, that you’ve just installed the 10.9.2 software update, and it’s mysteriously turned all your accounts into Standard ones. You could go to one Web site after another, hunting for a fix, repeating your search—or you could just type mavericks 10.9.2 standard accounts into Google. You’ll get your answers after just a few more seconds of clicking and exploring the results.

Help Online

These Web sites contain nothing but troubleshooting discussions, tools, and help:

§ Apple Discussion Groups (http://discussions.apple.com). The volume and quality of question-and-answer activity here dwarfs any other free source. If you’re polite and concise, you can post questions to the multitudes here and get more replies from them than you’ll know what to do with.

§ Apple’s help site (www.apple.com/support). Apple’s help site includes downloadable manuals, software updates, frequently asked questions, and many other resources.

Its search box is your ticket to the Knowledge Base, a collection of 100,000 technical articles that the Apple technicians themselves consult when answering calls for help.

§ MacFixIt (www.macfixit.com). The world’s one-stop resource for Mac troubleshooting advice; alas, you have to pay to access the good stuff.

Help by Telephone

Finally, consider contacting whoever sold you the component that’s making your life miserable: the printer company, scanner company, software company, or whatever.

If it’s an OS X problem, you can call Apple at 800-275-2273 (that’s 800-APL-CARE). For the first 90 days after your purchase of OS X, the technicians will answer your questions for free.

After that, unless you’ve paid for AppleCare for your Mac (a three-year extended warranty program), Apple will charge you to answer your questions. Fortunately, if the problem turns out to be Apple’s fault, they won’t charge you.