High Performance MySQL (2012)

Chapter 10. Replication

MySQL’s built-in replication is the foundation for building large, high-performance applications on top of MySQL, using the so-called “scale-out” architecture. Replication lets you configure one or more servers as replicas[144] of another server, keeping their data synchronized with the master copy. This is not just useful for high-performance applications—it is also the cornerstone of many strategies for high availability, scalability, disaster recovery, backups, analysis, data warehousing, and many other tasks. In fact, scalability and high availability are related topics, and we’ll be weaving these themes through this chapter and the next two.

In this chapter, we examine all aspects of replication. We begin with an overview of how it works, then look at basic server setup, designing more advanced replication configurations, and managing and optimizing your replicated servers. Although we generally focus a lot on performance in this book, we are equally concerned with correctness and reliability when it comes to replication, so’ll we show you how replication can fail and how to make it work well.

Replication Overview

The basic problem replication solves is keeping one server’s data synchronized with another’s. Many replicas can connect to a single master and stay in sync with it, and a replica can, in turn, act as a master. You can arrange masters and replicas in many different ways.

MySQL supports two kinds of replication: statement-based replication and row-based replication. Statement-based (or “logical”) replication has been available since MySQL 3.23. Row-based replication was added in MySQL 5.1. Both kinds work by recording changes in the master’s binary log[145] and replaying the log on the replica, and both are asynchronous—that is, the replica’s copy of the data isn’t guaranteed to be up-to-date at any given instant. There are no guarantees as to how large the latency on the replica might be. Large queries can make the replica fall seconds, minutes, or even hours behind the master.

MySQL’s replication is mostly backward-compatible. That is, a newer server can usually be a replica of an older server without trouble. However, older versions of the server are often unable to serve as replicas of newer versions: they might not understand new features or SQL syntax the newer server uses, and there might be differences in the file formats replication uses. For example, you can’t replicate from a MySQL 5.1 master to a MySQL 4.0 replica. It’s a good idea to test your replication setup before upgrading from one major or minor version to another, such as from 4.1 to 5.0, or 5.1 to 5.5. Upgrades within a minor version, such as from 5.1.51 to 5.1.58, are usually compatible—read the changelog to find out exactly what changed from version to version.

Replication generally doesn’t add much overhead on the master. It requires binary logging to be enabled on the master, which can have significant overhead, but you need that for proper backups and point-in-time recovery anyway. Aside from binary logging, each attached replica also adds a little load (mostly network I/O) on the master during normal operation. If replicas are reading old binary logs from the master, rather than just following along with the newest events, the overhead can be a lot higher due to the I/O required to read the old logs. This process can also cause some mutex contention that hinders transaction commits. Finally, if you are replicating a very high-throughput workload (say, 5,000 or more transactions per second) to many replicas, the overhead of waking up all the replica threads to send them the events can add up.

Replication is relatively good for scaling reads, which you can direct to a replica, but it’s not a good way to scale writes unless you design it right. Attaching many replicas to a master simply causes the writes to be done many times, once on each replica. The entire system is limited to the number of writes the weakest part can perform.

Replication is also wasteful with more than a few replicas, because it essentially duplicates a lot of data needlessly. For example, a single master with 10 replicas has 11 copies of the same data and duplicates most of the same data in 11 different caches. This is analogous to 11-way RAID 1 at the server level. This is not an economical use of hardware, yet it’s surprisingly common to see this type of replication setup. We discuss ways to alleviate this problem throughout the chapter.

Problems Solved by Replication

Here are some of the more common uses for replication:

Data distribution

MySQL’s replication is usually not very bandwidth-intensive, although, as we’ll see later, the row-based replication introduced in MySQL 5.1 can use much more bandwidth than the more traditional statement-based replication. You can also stop and start it at will. Thus, it’s useful for maintaining a copy of your data in a geographically distant location, such as a different data center. The distant replica can even work with a connection that’s intermittent (intentionally or otherwise). However, if you want your replicas to have very low replication lag, you’ll need a stable, low-latency link.

Load balancing

MySQL replication can help you distribute read queries across several servers, which works very well for read-intensive applications. You can do basic load balancing with a few simple code changes. On a small scale, you can use simplistic approaches such as hardcoded hostnames or round-robin DNS (which points a single hostname to multiple IP addresses). You can also take more sophisticated approaches. Standard load-balancing solutions, such as network load-balancing products, can work well for distributing load among MySQL servers. The Linux Virtual Server (LVS) project also works well. We cover load balancing in Chapter 11.

Backups

Replication is a valuable technique for helping with backups. However, a replica is neither a backup nor a substitute for backups.

High availability and failover

Replication can help avoid making MySQL a single point of failure in your application. A good failover system involving replication can help reduce downtime significantly. We cover failover in Chapter 12.

Testing MySQL upgrades

It’s common practice to set up a replica with an upgraded MySQL version and use it to ensure that your queries work as expected, before upgrading every instance.

How Replication Works

Before we get into the details of setting up replication, let’s look at how MySQL actually replicates data. At a high level, replication is a simple three-part process:

1. The master records changes to its data in its binary log. (These records are called binary log events.)

2. The replica copies the master’s binary log events to its relay log.

3. The replica replays the events in the relay log, applying the changes to its own data.

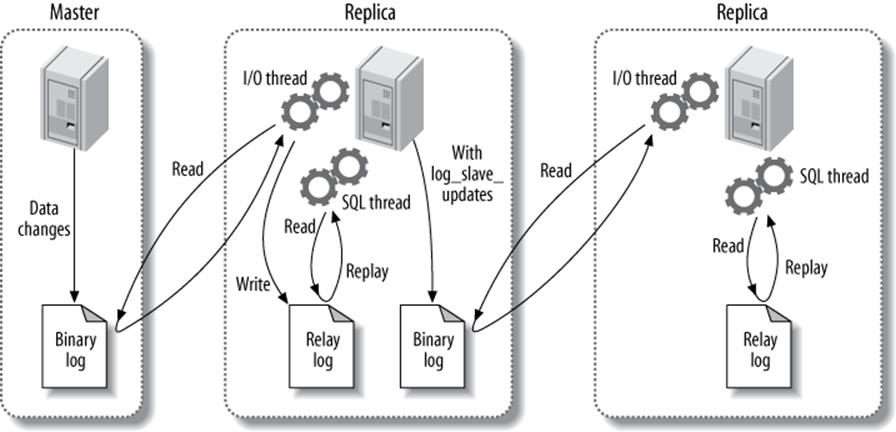

That’s just the overview—each of those steps is quite complex. Figure 10-1 illustrates replication in more detail.

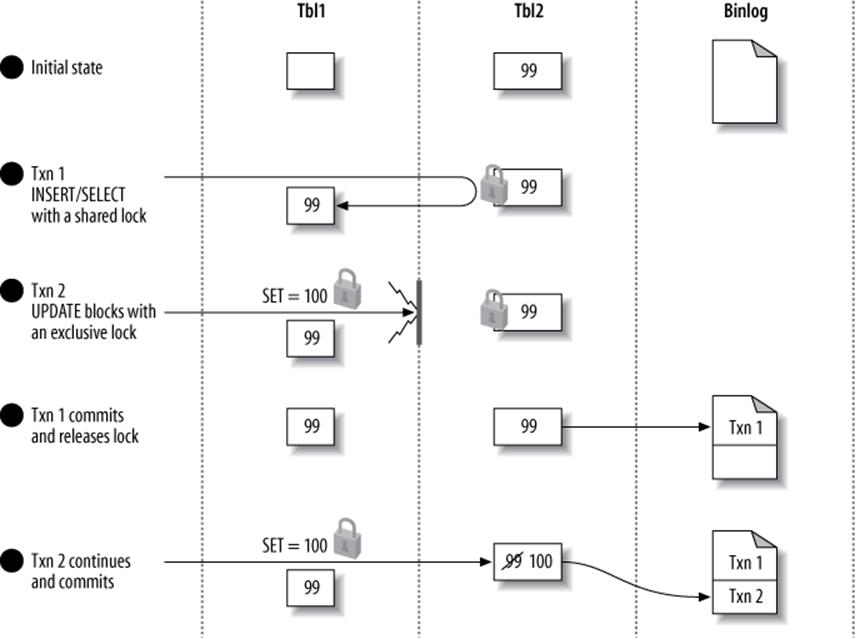

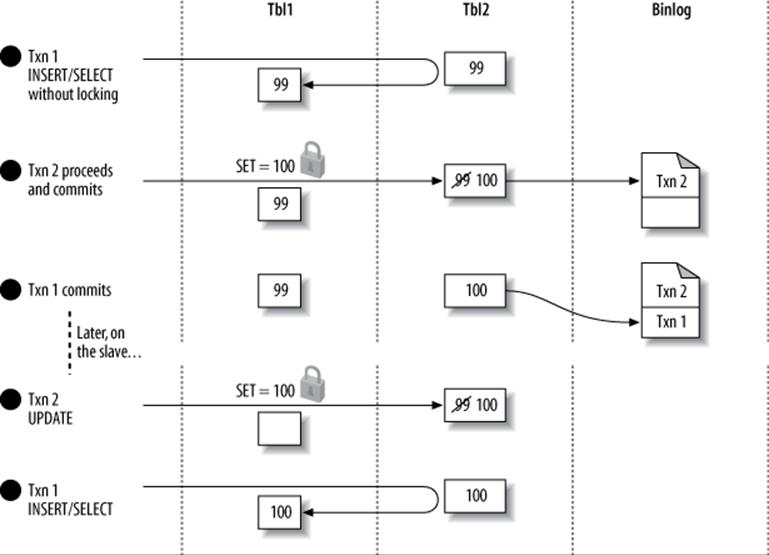

The first part of the process is binary logging on the master (we’ll show you how to set this up a bit later). Just before each transaction that updates data completes on the master, the master records the changes in its binary log. MySQL writes transactions serially in the binary log, even if the statements in the transactions were interleaved during execution. After writing the events to the binary log, the master tells the storage engine(s) to commit the transactions.

![How MySQL replication worksComment [Baron1]: All figures in this chapter need to be edited to replace “slave” with “replica.”](high.files/image031.jpg)

Figure 10-1. How MySQL replication works

The next step is for the replica to copy the master’s binary log to its own hard drive, into the so-called relay log. To begin, it starts a worker thread, called the I/O slave thread. The I/O thread opens an ordinary client connection to the master, then starts a special binlog dump process (there is no corresponding SQL command). The binlog dump process reads events from the master’s binary log. It doesn’t poll for events. If it catches up to the master, it goes to sleep and waits for the master to signal it when there are new events. The I/O thread writes the events to the replica’s relay log.

WARNING

Prior to MySQL 4.0, replication worked quite differently in many ways. For example, MySQL’s first replication functionality didn’t use a relay log, so replication used only two threads, not three. Most people are running more recent versions of the server, so we won’t mention any further details about very old versions of MySQL in this chapter.

The SQL slave thread handles the last part of the process. This thread reads and replays events from the relay log, thus updating the replica’s data to match the master’s. As long as this thread keeps up with the I/O thread, the relay log usually stays in the operating system’s cache, so relay logs have very low overhead. The events the SQL thread executes can optionally go into the replica’s own binary log, which is useful for scenarios we mention later in this chapter.

Figure 10-1 showed only the two replication threads that run on the replica, but there’s also a thread on the master: like any connection to a MySQL server, the connection that the replica opens to the master starts a thread on the master.

This replication architecture decouples the processes of fetching and replaying events on the replica, which allows them to be asynchronous. That is, the I/O thread can work independently of the SQL thread. It also places constraints on the replication process, the most important of which is that replication is serialized on the replica. This means updates that might have run in parallel (in different threads) on the master cannot be parallelized on the replica, because they’re executed in a single thread. As we’ll see later, this is a performance bottleneck for many workloads. There are some solutions to this, but most users are still subject to the single-threaded constraint.

[144] You might see replicas referred to as “slaves.” We avoid this term wherever possible.

[145] If you’re new to the binary log, you can find more information in Chapter 8, the rest of this chapter, and Chapter 15.

Setting Up Replication

Setting up replication is a fairly simple process in MySQL, but there are many variations on the basic steps, depending on the scenario. The most basic scenario is a freshly installed master and replica. At a high level, the process is as follows:

1. Set up replication accounts on each[146] server.

2. Configure the master and replica.

3. Instruct the replica to connect to and replicate from the master.

This assumes that many default settings will suffice, which is true if you’ve just installed the master and replica and they have the same data (the default mysql database). We show you here how to do each step in turn, assuming your servers are called server1 (IP address 192.168.0.1) andserver2 (IP address 192.168.0.2). We then explain how to initialize a replica from a server that’s already up and running and explore the recommended replication configuration.

Creating Replication Accounts

MySQL has a few special privileges that let the replication processes run. The slave I/O thread, which runs on the replica, makes a TCP/IP connection to the master. This means you must create a user account on the master and give it the proper privileges, so the I/O thread can connect as that user and read the master’s binary log. Here’s how to create that user account, which we’ll call repl:

mysql> GRANT REPLICATION SLAVE, REPLICATION CLIENT ON *.*

-> TO repl@'192.168.0.%' IDENTIFIED BY 'p4ssword',;

We create this user account on both the master and the replica. Note that we restricted the user to the local network, because the replication account has the ability to read all changes to the server, which makes it a privileged account. (Even though it has no ability to SELECT or change data, it can still see some of the data in the binary logs.)

NOTE

The replication user actually needs only the REPLICATION SLAVE privilege on the master and doesn’t really need the REPLICATION CLIENT privilege on either server. So why did we grant these privileges on both servers? We’re keeping things simple, actually. There are two reasons:

§ The account you use to monitor and manage replication will need the REPLICATION CLIENT privilege, and it’s easier to use the same account for both purposes (rather than creating a separate user account for this purpose).

§ If you set up the account on the master and then clone the replica from it, the replica will be set up correctly to act as a master, in case you want the replica and master to switch roles.

Configuring the Master and Replica

The next step is to enable a few settings on the master, which we assume is named server1. You need to enable binary logging and specify a server ID. Enter (or verify the presence of) the following lines in the master’s my.cnf file:

log_bin = mysql-bin

server_id = 10

The exact values are up to you. We’re taking the simplest route here, but you can do something more elaborate.

You must explicitly specify a unique server ID. We chose to use 10 instead of 1, because 1 is the default value a server will typically choose when no value is specified. (This is version-dependent; some MySQL versions just won’t work at all.) Therefore, using 1 can easily cause confusion and conflicts with servers that have no explicit server IDs. A common practice is to use the final octet of the server’s IP address, assuming it doesn’t change and is unique (i.e., the servers belong to only one subnet). You should choose some convention that makes sense to you and follow it.

If binary logging wasn’t already specified in the master’s configuration file, you’ll need to restart MySQL. To verify that the binary log file is created on the master, run SHOW MASTER STATUS and check that you get output similar to the following. MySQL will append some digits to the filename, so you won’t see a file with the exact name you specified:

mysql> SHOW MASTER STATUS;

+------------------+----------+--------------+------------------+

| File | Position | Binlog_Do_DB | Binlog_Ignore_DB |

+------------------+----------+--------------+------------------+

| mysql-bin.000001 | 98 | | |

+------------------+----------+--------------+------------------+

1 row in set (0.00 sec)

The replica requires a configuration in its my.cnf file similar to the master, and you’ll also need to restart MySQL on the replica:

log_bin = mysql-bin

server_id = 2

relay_log = /var/lib/mysql/mysql-relay-bin

log_slave_updates = 1

read_only = 1

Several of these options are not technically necessary, and for some we’re just making defaults explicit. In reality, only the server_id parameter is required on a replica, but we enabled log_bin too, and we gave the binary log file an explicit name. By default it is named after the server’s hostname, but that can cause problems if the hostname changes. We are using the same name for the master and replicas to keep things simple, but you can choose differently if you like.

We also added two other optional configuration parameters: relay_log (to specify the location and name of the relay log) and log_slave_updates (to make the replica log the replicated events to its own binary log). The latter option causes extra work for the replicas, but as you’ll see later, we have good reasons for adding these optional settings on every replica.

Some people enable just the binary log and not log_slave_updates, so they can see whether anything, such as a misconfigured application, is modifying data on the replica. If possible, it’s better to use the read_only configuration setting, which prevents anything but specially privileged threads from changing data. (Don’t grant your users more privileges than they need!) However, read_only is often not practical, especially for applications that need to be able to create tables on replicas.

WARNING

Don’t place replication configuration options such as master_host and master_port in the replica’s my.cnf file. This is an old, deprecated way to configure a replica. It can cause problems and has no benefits.

Starting the Replica

The next step is to tell the replica how to connect to the master and begin replaying its binary logs. You should not use the my.cnf file for this; instead, use the CHANGE MASTER TO statement. This statement replaces the corresponding my.cnf settings completely. It also lets you point the replica at a different master in the future, without stopping the server. Here’s the basic statement you’ll need to run on the replica to start replication:

mysql> CHANGE MASTER TO MASTER_HOST='server1',

-> MASTER_USER='repl',

-> MASTER_PASSWORD='p4ssword',

-> MASTER_LOG_FILE='mysql-bin.000001',

-> MASTER_LOG_POS=0;

The MASTER_LOG_POS parameter is set to 0 because this is the beginning of the log. After you run this, you should be able to inspect the output of SHOW SLAVE STATUS and see that the replica’s settings are correct:

mysql> SHOW SLAVE STATUS\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

Slave_IO_State:

Master_Host: server1

Master_User: repl

Master_Port: 3306

Connect_Retry: 60

Master_Log_File: mysql-bin.000001

Read_Master_Log_Pos: 4

Relay_Log_File: mysql-relay-bin.000001

Relay_Log_Pos: 4

Relay_Master_Log_File: mysql-bin.000001

Slave_IO_Running: No

Slave_SQL_Running: No

...omitted...

Seconds_Behind_Master: NULL

The Slave_IO_State, Slave_IO_Running, and Slave_SQL_Running columns show that the replication processes are not running. Astute readers will also notice that the log position is 4 instead of 0. That’s because 0 isn’t really a log position; it just means “at the start of the log file.” MySQL knows that the first event is really at position 4.[147]

To start replication, run the following command:

mysql> START SLAVE;

This command should produce no errors or output. Now inspect SHOW SLAVE STATUS again:

mysql> SHOW SLAVE STATUS\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

Slave_IO_State: Waiting for master to send event

Master_Host: server1

Master_User: repl

Master_Port: 3306

Connect_Retry: 60

Master_Log_File: mysql-bin.000001

Read_Master_Log_Pos: 164

Relay_Log_File: mysql-relay-bin.000001

Relay_Log_Pos: 164

Relay_Master_Log_File: mysql-bin.000001

Slave_IO_Running: Yes

Slave_SQL_Running: Yes

...omitted...

Seconds_Behind_Master: 0

Notice that the slave I/O and SQL threads are both running, and Seconds_Behind_Master is no longer NULL (we’ll examine what Seconds_Behind_Master means later). The I/O thread is waiting for an event from the master, which means it has fetched all of the master’s binary logs. The log positions have incremented, which means some events have been fetched and executed (your results will vary). If you make a change on the master, you should see the various file and position settings increment on the replica. You should also see the changes in the databases on the replica!

You will also be able to see the replication threads in the process list on both the master and the replica. On the master, you should see a connection created by the replica’s I/O thread:

mysql> SHOW PROCESSLIST\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

Id: 55

User: repl

Host: replica1.webcluster_1:54813

db: NULL

Command: Binlog Dump

Time: 610237

State: Has sent all binlog to slave; waiting for binlog to be updated

Info: NULL

On the replica, you should see two threads. One is the I/O thread, and the other is the SQL thread:

mysql> SHOW PROCESSLIST\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

Id: 1

User: system user

Host:

db: NULL

Command: Connect

Time: 611116

State: Waiting for master to send event

Info: NULL

*************************** 2. row ***************************

Id: 2

User: system user

Host:

db: NULL

Command: Connect

Time: 33

State: Has read all relay log; waiting for the slave I/O thread to update it

Info: NULL

The sample output we’ve shown comes from servers that have been running for a long time, which is why the I/O thread’s Time column on the master and the replica has a large value. The SQL thread has been idle for 33 seconds on the replica, which means no events have been replayed for 33 seconds.

These processes will always run under the “system user” user account, but the other column values might vary. For example, when the SQL thread is replaying an event on the replica, the Info column will show the query it is executing.

NOTE

If you just want to experiment with MySQL replication, Giuseppe Maxia’s MySQL Sandbox script (http://mysqlsandbox.net) can quickly start a throwaway installation from a freshly downloaded MySQL tarball. It takes just a few keystrokes and about 15 seconds to get a running master and two running replicas:

$ ./set_replication.pl /path/to/mysql-tarball.tar.gz

Initializing a Replica from Another Server

The previous setup instructions assumed that you started the master and replica with the default initial data after a fresh installation, so you implicitly had the same data on both servers and you knew the master’s binary log coordinates. This is not typically the case. You’ll usually have a master that has been up and running for some time, and you’ll want to synchronize a freshly installed replica with the master, even though it doesn’t have the master’s data.

There are several ways to initialize, or “clone,” a replica from another server. These include copying data from the master, cloning a replica from another replica, and starting a replica from a recent backup. You need three things to synchronize a replica with a master:

§ A snapshot of the master’s data at some point in time.

§ The master’s current log file, and the byte offset within that log at the exact point in time you took the snapshot. We refer to these two values as the log file coordinates, because together they identify a binary log position. You can find the master’s log file coordinates with the SHOW MASTER STATUS command.

§ The master’s binary log files from that time to the present.

Here are some ways to clone a replica from another server:

With a cold copy

One of the most basic ways to start a replica is to shut down the master-to-be and copy its files to the replica (see Appendix C for more on how to copy files efficiently). You can then start the master again, which begins a new binary log, and use CHANGE MASTER TO to start the replica at the beginning of that binary log. The disadvantage of this technique is obvious: you need to shut down the master while you make the copy.

With a warm copy

If you use only MyISAM tables, you can use mysqlhotcopy or rsync to copy files while the server is still running. See Chapter 15 for details.

Using mysqldump

If you use only InnoDB tables, you can use the following command to dump everything from the master, load it all into the replica, and change the replica’s coordinates to the corresponding position in the master’s binary log:

$ mysqldump --single-transaction --all-databases --master-data=1--host=server1 \

| mysql --host=server2

The --single-transaction option causes the dump to read the data as it existed at the beginning of the transaction. If you’re not using transactional tables, you can use the --lock-all-tables option to get a consistent dump of all tables.

With a snapshot or backup

As long as you know the corresponding binary log coordinates, you can use a snapshot from the master or a backup to initialize the replica (if you use a backup, this method requires that you’ve kept all of the master’s binary logs since the time of the backup). Just restore the backup or snapshot onto the replica, then use the appropriate binary log coordinates in CHANGE MASTER TO. There’s more detail about this in Chapter 15. You can use LVM snapshots, SAN snapshots, EBS snapshots—any snapshot will do.

With Percona XtraBackup

Percona XtraBackup is an open source hot backup tool we introduced several years ago. It can make backups without blocking the server’s operation, which makes it the cat’s meow for setting up replicas. You can create replicas by cloning the master, or by cloning an existing replica.

We show more details about how to use Percona XtraBackup in Chapter 15, but we’ll mention the relevant bits of functionality here. Just create the backup (either from the master, or from an existing replica), and restore it to the target machine. Then look in the backup for the correct position to start replication:

§ If you took the backup from the new replica’s master, you can start replication from the position mentioned in the xtrabackup_binlog_pos_innodb file.

§ If you took the backup from another replica, you can start replication from the position mentioned in the xtrabackup_slave_info file.

Using InnoDB Hot Backup or MySQL Enterprise Backup, both covered in Chapter 15, is another good way to initialize a replica.

From another replica

You can use any of the snapshot or copy techniques just mentioned to clone one replica from another. However, if you use mysqldump, the --master-data option doesn’t work.

Also, instead of using SHOW MASTER STATUS to get the master’s binary log coordinates, you’ll need to use SHOW SLAVE STATUS to find the position at which the replica was executing on the master when you snapshotted it.

The biggest disadvantage of cloning one replica from another is that if your replica has become out of sync with the master, you’ll be cloning bad data.

WARNING

Don’t use LOAD DATA FROM MASTER or LOAD TABLE FROM MASTER! They are obsolete, slow, and very dangerous. They also work only with MyISAM.

No matter what technique you choose, get comfortable with it, and document or script it. You will probably be doing it more than once, and you need to be able to do it in a pinch if something goes wrong.

Recommended Replication Configuration

There are many replication parameters, and most of them have at least some effect on data safety and performance. We explain later which rules to break and when. In this section, we show a recommended, “safe” replication configuration that minimizes the opportunities for problems.

The most important setting for binary logging on the master is sync_binlog:

sync_binlog=1

This makes MySQL synchronize the binary log’s contents to disk each time it commits a transaction, so you don’t lose log events if there’s a crash. If you disable this option, the server will do a little less work, but binary log entries could be corrupted or missing after a server crash. On a replica that doesn’t need to act as a master, this option creates unnecessary overhead. It applies only to the binary log, not to the relay log.

We also recommend using InnoDB if you can’t tolerate corrupt tables after a crash. MyISAM is fine if table corruption isn’t a big deal, but MyISAM tables are likely to be in an inconsistent state after a replica server crashes. Chances are good that a statement will have been incompletely applied to one or more tables, and the data will be inconsistent even after you’ve repaired the tables.

If you use InnoDB, we strongly recommend setting the following options on the master:

innodb_flush_logs_at_trx_commit=1 # Flush every log write

innodb_support_xa=1 # MySQL 5.0 and newer only

innodb_safe_binlog # MySQL 4.1 only, roughly equivalent to

# innodb_support_xa

These are the default settings in MySQL 5.0 and newer. We also recommend specifying a binary log base name explicitly, to create uniform binary log names on all servers and prevent changes in binary log names if the server’s hostname changes. You might not think that it’s a problem to have binary logs named after the server’s hostname automatically, but our experience is that it causes a lot of trouble when moving data between servers, cloning new replicas, and restoring backups, and in lots of other ways you wouldn’t expect. To avoid this, specify an argument to thelog_bin option, optionally with an absolute path, but certainly with the base name (as shown earlier in this chapter):

log_bin=/var/lib/mysql/mysql-bin # Good; specifies a path and base name

#log_bin # Bad; base name will be server’s hostname

On the replica, we also recommend enabling the following configuration options. We also recommend using an absolute path for the relay log location:

relay_log=/path/to/logs/relay-bin

skip_slave_start

read_only

The relay_log option prevents hostname-based relay log file names, which avoids the same problems we mentioned earlier that can happen on the master, and giving the absolute path to the logs avoids bugs in various versions of MySQL that can cause the relay logs to be created in an unexpected location. The skip_slave_start option will prevent the replica from starting automatically after a crash, which can give you a chance to repair a server if it has problems. If the replica starts automatically after a crash and is in an inconsistent state, it might cause so much additional corruption that you’ll have to throw away its data and start fresh.

The read_only option prevents most users from changing non-temporary tables. The exceptions are the replication SQL thread and threads with the SUPER privilege. This is one of the many reasons you should try to avoid giving your normal accounts the SUPER privilege.

Even if you’ve enabled all the options we’ve suggested, a replica can easily break after a crash, because the relay logs and master.info file aren’t crash-safe. They’re not even flushed to disk by default, and there’s no configuration option to control that behavior until MySQL 5.5. You should enable those options if you’re using MySQL 5.5 and if you don’t mind the performance overhead of the extra fsync() calls:

sync_master_info = 1

sync_relay_log = 1

sync_relay_log_info = 1

If a replica is very far behind its master, the slave I/O thread can write many relay logs. The replication SQL thread will remove them as soon as it finishes replaying them (you can change this with the relay_log_purge option), but if it is running far behind, the I/O thread could actually fill up the disk. The solution to this problem is the relay_log_space_limit configuration variable. If the total size of all the relay logs grows larger than this variable’s size, the I/O thread will stop and wait for the SQL thread to free up some more disk space.

Although this sounds nice, it can actually be a hidden problem. If the replica hasn’t fetched all the relay logs from the master, those logs might be lost forever if the master crashes. And this option has had some bugs in the past, and seems to be uncommonly used, so the risk of bugs is higher when you use it. Unless you’re worried about disk space, it’s probably a good idea to let the replica use as much space as it needs for relay logs. That’s why we haven’t included the relay_log_space_limit setting in our recommended configuration.

[146] This isn’t strictly necessary, but it’s something we recommend; we’ll explain later.

[147] Actually, as you can see in the earlier output from SHOW MASTER STATUS, it’s really at position 98. The master and s/slave/replica/ will work that out together once the s/slave/replica/ connects to the master, which hasn’t yet happened.

Replication Under the Hood

Now that we’ve explained some replication basics, let’s dive deeper into it. Let’s take a look at how replication really works, see what strengths and weaknesses it has as a result, and examine some more advanced replication configuration options.

Statement-Based Replication

MySQL 5.0 and earlier support only statement-based replication (also called logical replication). This is unusual in the database world. Statement-based replication works by recording the query that changed the data on the master. When the replica reads the event from the relay log and executes it, it is reexecuting the actual SQL query that the master executed. This arrangement has both benefits and drawbacks.

The most obvious benefit is that it’s fairly simple to implement. Simply logging and replaying any statement that changes data will, in theory, keep the replica in sync with the master. Another benefit of statement-based replication is that the binary log events tend to be reasonably compact. So, relatively speaking, statement-based replication doesn’t use a lot of bandwidth—a query that updates gigabytes of data might use only a few dozen bytes in the binary log. Also, the mysqlbinlog tool, which we mention throughout the chapter, is most convenient to use with statement-based logging.

In practice, however, statement-based replication is not as simple as it might seem, because many changes on the master can depend on factors besides just the query text. For example, the statements will execute at slightly—or possibly greatly—different times on the master and replica. As a result, MySQL’s binary log format includes more than just the query text; it also transmits several bits of metadata, such as the current timestamp. Even so, there are some statements that MySQL can’t replicate correctly, such as queries that use the CURRENT_USER() function. Stored routines and triggers are also problematic with statement-based replication.

Another issue with statement-based replication is that the modifications must be serializable. This requires more locking—sometimes significantly more. Not all storage engines work with statement-based replication, although those provided with the official MySQL server distribution up to and including MySQL 5.5 do.

You can find a complete list of statement-based replication’s limitations in the MySQL manual’s chapter on replication.

Row-Based Replication

MySQL 5.1 added support for row-based replication, which records the actual data changes in the binary log and is more similar to how most other database products implement replication. This scheme has several advantages and drawbacks of its own. The biggest advantages are that MySQL can replicate every statement correctly, and some statements can be replicated much more efficiently.

NOTE

Row-based logging is not backward-compatible. The mysqlbinlog utility distributed with MySQL 5.1 can read binary logs that contain events logged in row-based format (they are not human-readable, but the MySQL server can interpret them). However, versions of mysqlbinlog from earlier MySQL distributions will fail to recognize such log events and will exit with an error upon encountering them.

MySQL can replicate some changes more efficiently using row-based replication, because the replica doesn’t have to replay the queries that changed the rows on the master. Replaying some queries can be very expensive. For example, here’s a query that summarizes data from a very large table into a smaller table:

mysql> INSERT INTO summary_table(col1, col2, sum_col3)

-> SELECT col1, col2, sum(col3)

-> FROM enormous_table

-> GROUP BY col1, col2;

Imagine that there are only three unique combinations of col1 and col2 in the enormous_table table. This query will scan many rows in the source table but will result in only three rows in the destination table. Replicating this event as a statement will make the replica repeat all that work just to generate a few rows, but replicating it with row-based replication will be trivially cheap on the replica. In this case, row-based replication is much more efficient.

On the other hand, the following event is much cheaper to replicate with statement-based replication:

mysql> UPDATE enormous_table SET col1 = 0;

Using row-based replication for this query would be very expensive because it changes every row: every row would have to be written to the binary log, making the binary log event extremely large. This would place more load on the master during both logging and replication, and the slower logging might reduce concurrency.

Because neither format is perfect for every situation, MySQL can switch between statement-based and row-based replication dynamically. By default, it uses statement-based replication, but when it detects an event that cannot be replicated correctly with a statement, it switches to row-based replication. You can also control the format as needed by setting the binlog_format session variable.

It’s harder to do point-in-time recovery with a binary log that has events in row-based format, but not impossible. A log server can be helpful—more on that later.

Statement-Based or Row-Based: Which Is Better?

We’ve mentioned advantages and disadvantages for both replication formats. Which is better in practice?

In theory, row-based replication is probably better all-around, and in practice it generally works fine for most people. But its implementation is new enough that it hasn’t had years of little special-case behaviors baked in to support all the operational needs of MySQL administrators, and as a result it’s still a nonstarter for some people. Here’s a more complete discussion of the benefits and drawbacks of each format to help you decide which is more suitable for your needs:

Statement-based replication advantages

Logical replication works in more cases when the schema is different on the master and the replica. For example, it can be made to work in more cases where the tables have different but compatible data types, different column orders, and so on. This makes it easier to perform schema changes on a replica and then promote it to master, reducing downtime. Statement-based replication generally permits more operational flexibility.

The replication-applying process in statement-based replication is normal SQL execution, by and large. This means that all changes on the server are taking place through a well-understood mechanism, and it’s easy to inspect and determine what is happening if something isn’t working as expected.

Statement-based replication disadvantages

The list of things that can’t be replicated correctly through statement-based logging is so large that any given installation is likely to run into at least one of them. In particular, there were tons of bugs affecting replication of stored procedures, triggers, and so on in the 5.0 and 5.1 series of the server—so many that the way these are replicated was actually changed around a couple of times in attempts to make it work better. Bottom line: if you’re using triggers or stored procedures, don’t use statement-based replication unless you’re watching like a hawk to make sure you don’t run into problems.

There are also lots of problems with temporary tables, mixtures of storage engines, specific SQL constructs, nondeterministic statements, and so on. These range from annoying to show-stopping.

Row-based replication advantages

There are a lot fewer cases that don’t work in row-based replication. It works correctly with all SQL constructs, with triggers, with stored procedures, and so on. It generally only fails when you’re trying to do something clever such as schema changes on the replica.

It also creates opportunities for reduced locking, because it doesn’t require such strong serialization to be repeatable.

Row-based replication works by logging the data that’s changed, so the binary log is a record of what has actually changed on the master. You don’t have to look at a statement and guess whether it changed any data. Thus, in some ways you actually know more about what’s changed in your server, and you have a better record of the changes. Also, in some cases the row-based binary logs record what the data used to be, so they can potentially be more useful for some kinds of data recovery efforts.

Row-based replication can be less CPU-intensive in many cases, due to the lack of a need to plan and execute queries in the same way that statement-based replication does.

Finally, row-based replication can help you find and solve data inconsistencies more quickly in some cases. For example, statement-based replication won’t fail if you update a row on the master and it doesn’t exist on the replica, but row-based replication will throw an error and stop.

Row-based replication disadvantages

The statement isn’t included in the log event, so it can be tough to figure out what SQL was executed. This is important in many cases, in addition to knowing the row changes. (This will probably be fixed in a future version of MySQL.)

Replication changes are applied on replicas in a completely different manner—it isn’t SQL being executed. In fact, the process of applying row-based changes is pretty much a black box with no visibility into what the server is doing, and it’s not well documented or explained, so when things don’t work right, it can be tough to troubleshoot. As an example, if the replica chooses an inefficient way to find rows to change, you can’t observe that.

If you have multiple levels of replication servers, and all are configured for row-based logging, a statement that you execute while your session-level @@binlog_format variable is set to STATEMENT will be logged as a statement on the server where it originates, but then the first-level replicas might relay the event in row-based format to further replicas in the chain. That is, your desired statement-based logging will get switched back to row-based logging as it propagates through the replication topology.

Row-based logging can’t handle some things that statement-based logging can, such as schema changes on replicas.

Replication will sometimes halt in cases where statement-based replication would continue, such as when the replica is missing a row that’s supposed to be changed. This could be regarded as a good thing. In any case, it is configurable with the slave_exec_mode option.

Many of these disadvantages are being lifted as time passes, but at the time of writing, they are still true in most production deployments.

Replication Files

Let’s take a look at some of the files replication uses. You already know about the binary log and the relay log, but there are several other files, too. Where MySQL places them depends mostly on your configuration settings. Different MySQL versions place them in different directories by default. You can probably find them either in the data directory or in the directory that contains the server’s .pid file (possibly /var/run/mysqld/ on Unix-like systems). Here they are:

mysql-bin.index

A server that has binary logging enabled will also have a file named the same as the binary logs, but with a .index suffix. This file keeps track of the binary log files that exist on disk. It is not an index in the sense of a table’s index; rather, each line in the file contains the filename of a binary log file.

You might be tempted to think that this file is redundant and can be deleted (after all, MySQL could just look at the disk to find its files), but don’t. MySQL relies on this index file, and it will not recognize a binary log file unless it’s mentioned here.

mysql-relay-bin.index

This file serves the same purpose for the relay logs as the binary log index file does for the binary logs.

master.info

This file contains the information a replica needs to connect to its master. The format is plain text (one value per line) and varies between MySQL versions. Don’t delete it, or your replica will not know how to connect to its master after it restarts. This file contains the replication user’s password, in plain text, so you might want to restrict its permissions.

relay-log.info

This file contains the replica’s current binary log and relay log coordinates (i.e., the replica’s position on the master). Don’t delete this either, or the replica will forget where it was replicating from after a restart and might try to replay statements it has already executed.

These files are a rather crude way of recording MySQL’s replication and logging state. Unfortunately, they are not written synchronously, so if your server loses power and the files haven’t yet been flushed to disk, they can be inaccurate when the server restarts. This is improved in MySQL 5.5, as mentioned previously.

The .index files interact with another setting, expire_logs_days, which specifies how MySQL should purge expired binary logs. If the mysql-bin.index files mention files that don’t exist on disk, automatic purging will not work in some MySQL versions; in fact, even the PURGE MASTER LOGS statement won’t work. The solution to this problem is generally to use the MySQL server to manage the binary logs, so it doesn’t get confused. (That is, you shouldn’t use rm to purge files yourself.)

You need to implement some sort of log purging strategy explicitly, either with expire_logs_days or another means, or MySQL will fill up the disk with binary logs. You should consider your backup policy when you do this.

Sending Replication Events to Other Replicas

The log_slave_updates option lets you use a replica as a master of other replicas. It instructs MySQL to write the events the replication SQL thread executes into its own binary log, which its own replicas can then retrieve and execute. Figure 10-2 illustrates this.

Figure 10-2. Passing on a replication event to further replicas

In this scenario, a change on the master causes an event to be written to its binary log. The first replica then fetches and executes the event. At this point, the event’s life would normally be over, but because log_slave_updates is enabled, the replica writes it to its binary log instead. Now the second replica can retrieve the event into its own relay log and execute it. This configuration means that changes on the original master can propagate to replicas that are not attached to it directly. We prefer setting log_slave_updates by default because it lets you connect a replica without having to restart the server.

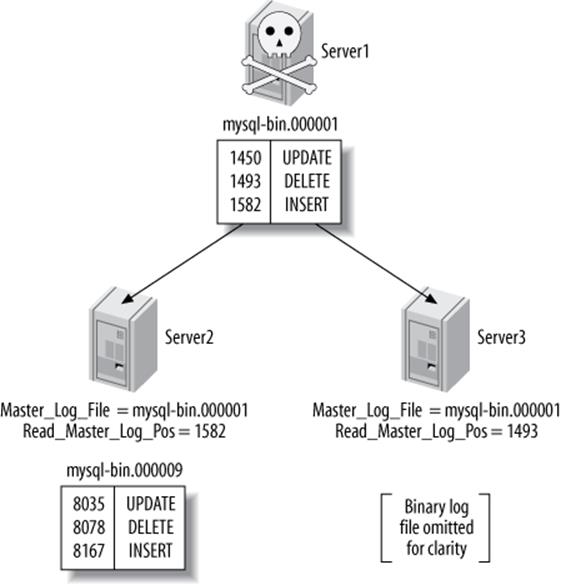

When the first replica writes a binary log event from the master into its own binary log, that event will almost certainly be at a different position in the log from its position on the master—that is, it could be in a different log file or at a different numerical position within the log file. This means you can’t assume all servers that are at the same logical point in replication will have the same log coordinates. As we’ll see later, this makes it quite complicated to do some tasks, such as changing replicas to a different master or promoting a replica to be the master.

Unless you’ve taken care to give each server a unique server ID, configuring a replica in this manner can cause subtle errors and might even cause replication to complain and stop. One of the more common questions about replication configuration is why one needs to specify the server ID. Shouldn’t MySQL be able to replicate statements without knowing where they originated? Why does MySQL care whether the server ID is globally unique? The answer to this question lies in how MySQL prevents an infinite loop in replication. When the replication SQL thread reads the relay log, it discards any event whose server ID matches its own. This breaks infinite loops in replication. Preventing infinite loops is important for some of the more useful replication topologies, such as master-master replication.[148]

NOTE

If you’re having trouble getting replication set up, the server ID is one of the things you should check. It’s not enough to just inspect the @@server_id variable. It has a default value, but replication won’t work unless it’s explicitly set, either in my.cnf or via a SET command. If you use a SET command, be sure you update the configuration file too, or your settings won’t survive a server restart.

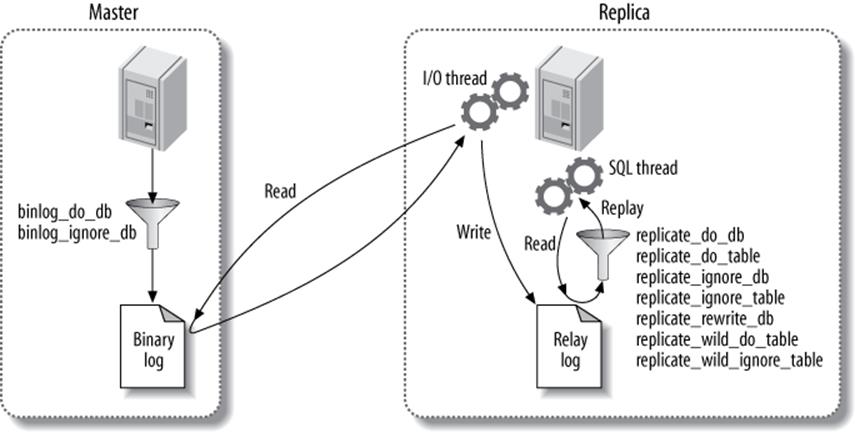

Replication Filters

Replication filtering options let you replicate just part of a server’s data, which is much less of a good thing than you might think. There are two kinds of replication filters: those that filter events out of the binary log on the master, and those that filter events coming from the relay log on the replica. Figure 10-3 illustrates the two types.

Figure 10-3. Replication filtering options

The options that control binary log filtering are binlog_do_db and binlog_ignore_db. You should not enable these, as we’ll explain in a moment, unless you think you’ll enjoy explaining to your boss why the data is gone permanently and can’t be recovered.

On the replica, the replicate_* options filter events as the replication SQL thread reads them from the relay log. You can replicate or ignore one or more databases, rewrite one database to another database, and replicate or ignore tables based on LIKE pattern matching syntax.

The most important thing to understand about these options is that the *_do_db and *_ignore_db options, both on the master and on the replica, do not work as you might expect. You might think they filter on the object’s database name, but they actually filter on the current default database.[149] That is, if you execute the following statements on the master:

mysql> USE test;

mysql> DELETE FROM sakila.film;

the *_do_db and *_ignore_db parameters will filter the DELETE statement on test, not on sakila. This is not usually what you want, and it can cause the wrong statements to be replicated or ignored. The *_do_db and *_ignore_db parameters have uses, but they’re limited and rare, and you should be very careful with them. If you use these parameters, it’s very easy to for replication to get out of sync or fail.

WARNING

The binlog_do_db and binlog_ignore_db options don’t just have the potential to break replication; they also make it impossible to do point-in-time recovery from a backup. For most situations, you should never use them. They can cause endless grief. We show some alternative ways to filter replication with Blackhole tables later in this chapter.

In general, replication filters are a problem waiting to happen. For example, suppose you want to prevent privilege changes from propagating to replicas, a fairly common goal. (The desire to do this should probably tip you off that you’re doing something wrong; there are probably other ways to accomplish your real goal.) Replication filters on the system tables will certainly prevent GRANT statements from replicating, but they will prevent events and routines from replicating, too. Such unforeseen consequences are a reason to be careful with filters. It might be a better idea to prevent specific statements from being replicated, usually with SET SQL_LOG_BIN=0, though that practice has its own hazards. In general, you should use replication filters very carefully, and only if you really need them, because they make it so easy to break replication and cause problems that will manifest when it’s least convenient, such as during disaster recovery.

The filtering options are well documented in the MySQL manual, so we won’t repeat the details here.

[148] Statements running around in infinite loops are also one of the many joys of multi-server ring replication topologies, which we’ll show later. Avoid ring replication like the plague.

[149] If you’re using statement-based replication, that is. If you’re using row-based replication, they don’t behave quite the same (another good reason to stay away from them).

Replication Topologies

You can set up MySQL replication for almost any configuration of masters and replicas, with the limitation that a given MySQL replica instance can have only one master. Many complex topologies are possible, but even the simple ones can be very flexible. A single topology can have many different uses. The variety of ways you can use replication could easily fill its own book.

We’ve already seen how to set up a master with a single replica. In this section, we look at some other common topologies and discuss their strengths and limitations. As we go, remember these basic rules:

§ A MySQL replica instance can have only one master.

§ Every replica must have a unique server ID.

§ A master can have many replicas (or, correspondingly, a replica can have many siblings).

§ A replica can propagate changes from its master, and be the master of other replicas, if you enable log_slave_updates.

Master and Multiple Replicas

Aside from the basic two-server master-replica setup we’ve already mentioned, this is the simplest replication topology. In fact, it’s just as simple as the basic setup, because the replicas don’t interact with each other;[150] they each connect only to the master. Figure 10-4 shows this arrangement.

Figure 10-4. A master with multiple replicas

This configuration is most useful when you have few writes and many reads. You can spread reads across any number of replicas, up to the point where the replicas put too much load on the master or network bandwidth from the master to the replicas becomes a problem. You can set up many replicas at once, or add replicas as you need them, using the same steps we showed earlier in this chapter.

Although this is a very simple topology, it is flexible enough to fill many needs. Here are just a few ideas:

§ Use different replicas for different roles (for example, add different indexes or use different storage engines).

§ Set up one of the replicas as a standby master, with no traffic other than replication.

§ Put one of the replicas in a remote data center for disaster recovery.

§ Time-delay one or more of the replicas for disaster recovery.

§ Use one of the replicas for backups, for training, or as a development or staging server.

One of the reasons this topology is popular is that it avoids many of the complexities that come with other configurations. Here’s an example: it’s easy to compare one replica to another in terms of binary log positions on the master, because they’ll all be the same. In other words, if you stop all the replicas at the same logical point in replication, they’ll all be reading from the same physical position in the master’s logs. This is a nice property that simplifies many administrative tasks, such as promoting a replica to be the master.

This property holds only among “sibling” replicas. It’s more complicated to compare log positions between servers that aren’t in a direct master-replica or sibling relationship. Many of the topologies we mention later, such as tree replication or distribution masters, make it harder to figure out where in the logical sequence of events a replica is really replicating.

Master-Master in Active-Active Mode

Master-master replication (also known as dual-master or bidirectional replication) involves two servers, each configured as both a master and a replica of the other—in other words, a pair of co-masters. Figure 10-5 shows the setup.

Figure 10-5. Master-master replication

MYSQL DOES NOT SUPPORT MULTISOURCE REPLICATION

We use the term multisource replication very specifically to describe the scenario where there is a replica with more than one master. Regardless of what you might have been told, MySQL (unlike some other database servers) does not support the configuration illustrated in Figure 10-6 at present. However, we show you some ways to emulate multisource replication later in this chapter.

FIGURE 10-6. MYSQL DOES NOT SUPPORT MULTISOURCE REPLICATION

Master-master replication in active-active mode has uses, but they’re generally special-purpose. One possible use is for geographically separated offices, where each office needs its own locally writable copy of data.

The biggest problem with such a configuration is how to handle conflicting changes. The list of possible problems caused by having two writable co-masters is very long. Problems usually show up when a query changes the same row simultaneously on both servers or inserts into a table with an AUTO_INCREMENT column at the same time on both servers.[151]

MySQL 5.0 added some replication features that make this type of replication setup slightly less of a foot-gun: the auto_increment_increment and auto_increment_offset settings. These settings let servers autogenerate nonconflicting values for INSERT queries. However, allowing writes to both masters is still extremely dangerous. Updates that happen in a different order on the two machines can still cause the data to silently become out of sync. For example, imagine you have a single-column, single-row table containing the value 1. Now suppose these two statements execute simultaneously:

§ On the first co-master:

mysql> UPDATE tbl SET col=col + 1;

§ On the second:

mysql> UPDATE tbl SET col=col * 2;

The result? One server has the value 4, and the other has the value 3. And yet, there are no replication errors at all.

Data getting out of sync is only the beginning. What if normal replication stops with an error, but applications keep writing to both servers? You can’t just clone one of the servers from the other, because each of them will have changes that you need to copy to the other. Solving this problem is likely to be very hard. Consider yourself warned!

If you set up a master-master active-active configuration carefully, perhaps with well-partitioned data and privileges, and if you really know what you’re doing, you can avoid some of these problems.[152] However, it’s hard to do well, and there’s almost always a better way to achieve what you need.

In general, allowing writes on both servers causes way more trouble than it’s worth. However, an active-passive configuration is very useful indeed, as you’ll see in the next section.

Master-Master in Active-Passive Mode

There’s a variation on master-master replication that avoids the pitfalls we just discussed and is, in fact, a very powerful way to design fault-tolerant and highly available systems. The main difference is that one of the servers is a read-only “passive” server, as shown in Figure 10-7.

Figure 10-7. Master-master replication in active-passive mode

This configuration lets you swap the active and passive server roles back and forth very easily, because the servers’ configurations are symmetrical. This makes failover and failback easy. It also lets you perform maintenance, optimize tables, upgrade your operating system (or application, or hardware), and do other tasks without any downtime.

For example, running an ALTER TABLE statement locks the entire table, blocking reads and writes to it. This can take a long time and disrupt service. However, the master-master configuration lets you stop the replication threads on the active server (so it doesn’t process any updates from the passive server), alter the table on the passive server, switch the roles, and restart replication on the formerly active server.[153] That server then reads its relay log and executes the same ALTER TABLE statement. Again, this might take a long time, but it doesn’t matter because the server isn’t serving any live queries.

The active-passive master-master topology lets you sidestep many other problems and limitations in MySQL. There are some toolsets to help with this type of operational task, too.

Let’s see how to configure a master-master pair. Perform these steps on both servers, so they end up with symmetrical configurations:

1. Ensure that the servers have exactly the same data.

2. Enable binary logging, choose unique server IDs, and add replication accounts.

3. Enable logging replica updates. This is crucial for failover and failback, as we’ll see later.

4. Optionally configure the passive server to be read-only to prevent changes that might conflict with changes on the active server.

5. Start each server’s MySQL instance.

6. Configure each server as a replica of the other, beginning with the newly created binary log.

Now let’s trace what happens when there’s a change to the active server. The change gets written to its binary log and flows through replication to the passive server’s relay log. The passive server executes the query and writes the event to its own binary log, because you enabledlog_slave_updates. The active server then ignores the event, because the server ID in the event matches its own. See the section Changing Masters to learn how to switch roles.

Setting up an active-passive master-master topology is a little like creating a hot spare in some ways, except that you can use the “spare” to boost performance. You can use it for read queries, backups, “offline” maintenance, upgrades, and so on—things you can’t do with a true hot spare. However, you cannot use it to gain better write performance than you can get with a single server (more about that later).

As we discuss more scenarios and uses for replication, we’ll come back to this configuration. It is a very important and common replication topology.

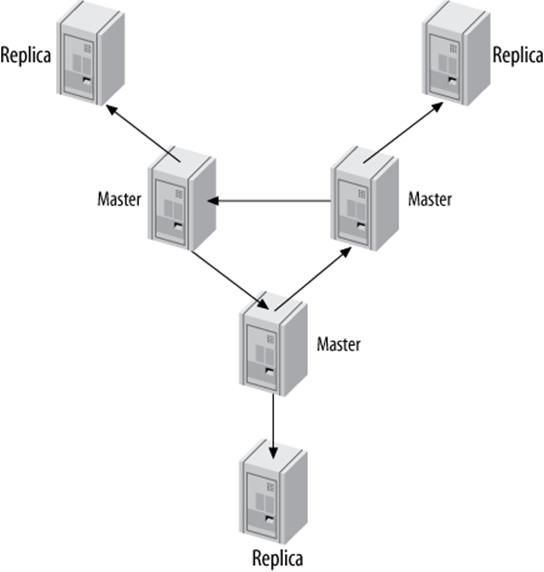

Master-Master with Replicas

A related configuration is to add one or more replicas to each co-master, as shown in Figure 10-8.

Figure 10-8. Master-master topology with replicas

The advantage of this configuration is extra redundancy. In a geographically distributed replication topology, it removes the single point of failure at each site. You can also offload read-intensive queries to the replicas, as usual.

If you’re using a master-master topology locally for fast failover, this configuration is still useful. Promoting one of the replicas to replace a failed master is possible, although it’s a little more complex. The same is true of moving one of the replicas to point to a different master. The added complexity is an important consideration.

Ring Replication

The dual-master configuration is really just a special case[154] of the ring replication configuration, shown in Figure 10-9. A ring has three or more masters. Each server is a replica of the server before it in the ring, and a master of the server after it. This topology is also called circular replication.

Rings don’t have some of the key benefits of a master-master setup, such as symmetrical configuration and easy failover. They also depend completely on every node in the ring being available, which greatly increases the probability of the entire system failing. And if you remove one of the nodes from the ring, any replication events that originated at that node can go into an infinite loop: they’ll cycle forever through the chain of servers, because the only server that will filter out an event based on its server ID is the server that created it. In general, rings are brittle and best avoided, no matter how clever you are.

Figure 10-9. A replication ring topology

You can mitigate some of the risk of a ring replication setup by adding replicas to provide redundancy at each site, as shown in Figure 10-10. This merely protects against the risk of a server failing, though. A loss of power or any other problem that affects any connection between the sites will still break the entire ring.

Figure 10-10. A replication ring with additional replicas at each site

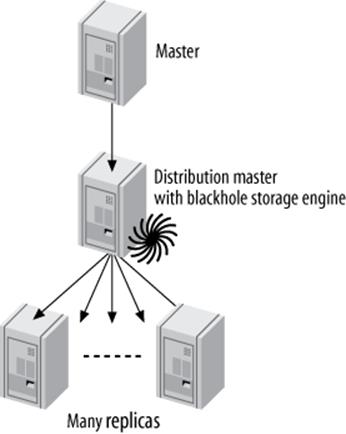

Master, Distribution Master, and Replicas

We’ve mentioned that replicas can place quite a load on the master if there are enough of them. Each replica creates a new thread on the master, which executes the special binlog dump command. This command reads the data from the binary log and sends it to the replica. The work is repeated for each replica; they don’t share the resources required for a binlog dump.

If there are many replicas and there’s a particularly large binary log event, such as a huge LOAD DATA INFILE, the master’s load can go up significantly. The master might even run out of memory and crash because of all the replicas requesting the same huge event at the same time. On the other hand, if the replicas are all requesting different binlog events that aren’t in the filesystem cache anymore, that can cause a lot of disk seeks, which might also interfere with the master’s performance and cause mutex contention.

For this reason, if you need many replicas, it’s often a good idea to remove the load from the master and use a distribution master. A distribution master is a replica whose only purpose is to read and serve the binary logs from the master. Many replicas can connect to the distribution master, which insulates the original master from the load. To remove the work of actually executing the queries on the distribution master, you can change its tables to the Blackhole storage engine, as shown in Figure 10-11.

Figure 10-11. A master, a distribution master, and many replicas

It’s hard to say exactly how many replicas a master can handle before it needs a distribution master. As a very rough rule of thumb, if your master is running near its full capacity, you might not want to put more than about 10 replicas on it. If there’s very little write activity, or you’re replicating only a fraction of the tables, the master can probably serve many more replicas. Additionally, you don’t have to limit yourself to just one distribution master. You can use several if you need to replicate to a really large number of replicas, or you can even use a pyramid of distribution masters. In some cases it also helps to set slave_compressed_protocol, to save some bandwidth on the master. This is most helpful for cross–data center replication.

You can also use the distribution master for other purposes, such as applying filters and rewrite rules to the binary log events. This is much more efficient than repeating the logging, rewriting, and filtering on each replica.

If you use Blackhole tables on the distribution master, it will be able to serve more replicas than it could otherwise. The distribution master will execute the queries, but the queries will be extremely cheap, because the Blackhole tables will not have any data. The drawback of Blackhole tables is that they have bugs, such as forgetting to put autoincrementing IDs into their binary logs in some circumstances, so be very careful with Blackhole tables if you use them.[155]

A common question is how to ensure that all tables on the distribution master use the Blackhole storage engine. What if someone creates a new table on the master and specifies a different storage engine? Indeed, the same issue arises whenever you want to use a different storage engine on a replica. The usual solution is to set the server’s storage_engine option:

storage_engine = blackhole

This will affect only CREATE TABLE statements that don’t specify a storage engine explicitly. If you have an existing application that you can’t control, this topology might be fragile. You can disable InnoDB and make tables fall back to MyISAM with the skip_innodb option, but you can’t disable the MyISAM or Memory engines.

The other major drawback is the difficulty of replacing the master with one of the (ultimate) replicas. It’s hard to promote one of the replicas into its place, because the intermediate master ensures that they will almost always have different binary log coordinates than the original master does.[156]

Tree or Pyramid

If you’re replicating a master to a very large number of replicas—whether you’re distributing data geographically or just trying to build in more read capacity—it can be more manageable to use a pyramid design, as illustrated in Figure 10-12.

Figure 10-12. A pyramid replication topology

The advantage of this design is that it eases the load on the master, just as the distribution master did in the previous section. The disadvantage is that any failure in an intermediate level will affect multiple servers, which wouldn’t happen if the replicas were each attached to the master directly. Also, the more intermediate levels you have, the harder and more complicated it is to handle failures.

Custom Replication Solutions

MySQL replication is flexible enough that you can often design a custom solution for your application’s needs. You’ll typically use some combination of filtering, distribution, and replicating to different storage engines. You can also use “hacks,” such as replicating to and from servers that use the Blackhole storage engine (as discussed earlier in this chapter). Your design can be as elaborate as you want. The biggest limitations are what you can monitor and administer reasonably and what resource constraints you have (network bandwidth, CPU power, etc.).

Selective replication

To take advantage of locality of reference and keep your working set in memory for reads, you can replicate a small amount of data to each of many replicas. If each replica has a fraction of the master’s data and you direct reads to the replicas, you can make much better use of the memory on each replica. Each replica will also have only a fraction of the master’s write load, so the master can become more powerful without making the replicas fall behind.

This scenario is similar in some respects to the horizontal data partitioning we’ll talk more about in the next chapter, but it has the advantage that one server still hosts all the data—the master. This means you never have to look on more than one server for the data needed for a write query, and if you have read queries that need data that doesn’t all exist on any single replica server, you have the option of doing those reads on the master instead. Even if you can’t do all reads on the replicas, you should be able to move many of them off the master.

The simplest way to do this is to partition the data into different databases on the master, and then replicate each database to a different replica server. For example, if you want to replicate data for each department in your company to a different replica, you can create databases called sales,marketing, procurement, and so on. Each replica should then have a replicate_wild_do_table configuration option that limits its data to the given database. Here’s the configuration option for the sales database:

replicate_wild_do_table = sales.%

Filtering with a distribution master is also useful. For example, if you want to replicate just part of a heavily loaded server across a slow or very expensive network, you can use a local distribution master with Blackhole tables and filtering rules. The distribution master can have replication filters that remove undesired entries from its logs. This can help avoid dangerous logging settings on the master, and it doesn’t require you to transfer all the logs across the network to the remote replicas.

Separating functions

Many applications have a mixture of online transaction processing (OLTP) and online analytical processing (OLAP) queries. OLTP queries tend to be short and transactional. OLAP queries are usually large and slow and don’t require absolutely up-to-date data. The two types of queries also place very different stresses on the server. Thus, they perform best on servers that are configured differently and perhaps even use different storage engines and hardware.

A common solution to this problem is to replicate the OLTP server’s data to replicas specifically designed for the OLAP workload. These replicas can have different hardware, configurations, indexes, and/or storage engines. If you dedicate a replica to OLAP queries, you might also be able to tolerate more replication lag or otherwise degraded quality of service on that replica. That might mean you can use it for tasks that would result in unacceptable performance on a nondedicated replica, such as executing very long-running queries.

No special replication setup is required, although you might choose to omit some of the data from the master if you’ll achieve significant savings by not having it on the replica. Filtering out even a small amount of data with replication filters on the relay log might help reduce I/O and cache activity.

Data archiving

You can archive data on a replica server—that is, keep it on the replica but remove it from the master—by running delete queries on the master and ensuring that those queries don’t execute on the replica. There are two common ways to do this: one is to selectively disable binary logging on the master, and the other is to use replicate_ignore_db rules on the replica. (Yes, both are dangerous.)

The first method requires executing SET SQL_LOG_BIN=0 in the process that purges the data on the master, then purging the data. This has the advantage of not requiring any special replication configuration on the replica, and because the statements aren’t even logged to the master’s binary log, it’s slightly more efficient there too. The main disadvantage is that you won’t be able to use the binary log on the master for auditing or point-in-time recovery anymore, because it won’t contain every modification made to the master’s data. It also requires the SUPER privilege.

The second technique is to USE a certain database on the master before executing the statements that purge the data. For example, you can create a database named purge, and then specify replicate_ignore_db=purge in the replica’s my.cnf file and restart the server. The replica will ignore statements that USE this database. This approach doesn’t have the first technique’s weaknesses, but it has the (minor) drawback of making the replica fetch binary log events it doesn’t need. There’s also a potential for someone to mistakenly execute non-purge queries in the purgedatabase, thus causing the replica not to replay events you want it to.

Percona Toolkit’s pt-archiver tool supports both methods.

NOTE

A third option is to use binlog_ignore_db to filter out replication events, but as we stated earlier, we consider this too dangerous.

Using replicas for full-text searches

Many applications require a combination of transactions and full-text searches. However, at the time of writing only MyISAM tables offer built-in full-text search capabilities, and MyISAM doesn’t support transactions. (There’s a laboratory preview of InnoDB full-text search in MySQL 5.6, but it isn’t GA yet.) A common workaround is to configure a replica for full-text searches by changing the storage engine for certain tables to MyISAM on the replica. You can then add full-text indexes and perform full-text search queries on the replica. This avoids potential replication problems with transactional and nontransactional storage engines in the same query on the master, and it relieves the master of the extra work of maintaining the full-text indexes.

Read-only replicas

Many organizations prefer replicas to be read-only, so unintended changes don’t break replication. You can achieve this with the read_only configuration variable. It disables most writes: the exceptions are the replica processes, users who have the SUPER privilege, and temporary tables. This is perfect as long as you don’t give the SUPER privilege to ordinary users, which you shouldn’t do anyway.

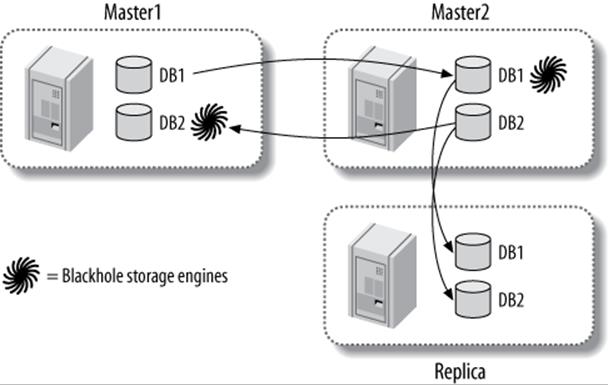

Emulating multisource replication

MySQL does not currently support multisource replication (i.e., a replica with more than one master). However, you can emulate this topology by changing a replica to point at different masters in turn. For example, you can point the replica at master A and let it run for a while, then point it at master B for a while, and then switch it back to master A again. How well this will work depends on your data and how much work the two masters will cause the single replica to do. If your masters are relatively lightly loaded and their updates won’t conflict at all, it might work very well.

You’ll need to do a little work to keep track of the binary log coordinates for each master. You also might want to ensure that the replica’s I/O thread doesn’t fetch more data than you intend it to execute on each cycle; otherwise, you could increase the network traffic and load on the master significantly by fetching and throwing away a lot of data on each cycle.

You can also emulate multisource replication using master-master (or ring) replication and the Blackhole storage engine with a replica, as depicted in Figure 10-13.

Figure 10-13. Emulating multisource replication with dual masters and the Blackhole storage engine

In this configuration, the two masters each contain their own data. They each also contain the tables from the other master, but use the Blackhole storage engine to avoid actually storing the data in those tables. A replica is attached to one of the co-masters—it doesn’t matter which one. This replica does not use the Blackhole storage engine at all, so it is effectively a replica of both masters.

In fact, it’s not really necessary to use a master-master topology to achieve this. You can simply replicate from server1 to server2 to the replica. If server2 uses the Blackhole storage engine for tables replicated from server1, it will not contain any data from server1, as shown inFigure 10-14.

Figure 10-14. Another way to emulate multisource replication

Either of these configurations can suffer from the usual problems, such as conflicting updates and CREATE TABLE statements that explicitly specify a storage engine.

Another option is to use Continuent’s Tungsten Replicator, which we’ll discuss later in this chapter.

Creating a log server

One of the things you can do with MySQL replication is create a “log server” with no data, whose only purpose is to make it easy to replay and/or filter binary log events. As you’ll see later in this chapter, this is very useful for restarting replication after crashes. It’s also useful for point-in-time recovery, which we discuss in Chapter 15.