High Performance MySQL (2012)

Chapter 7. Advanced MySQL Features

MySQL 5.0 and 5.1 introduced many features, such as partitioning and triggers, which are familiar to users with a background in other database servers. The addition of these features attracted many new users to MySQL. However, their performance implications did not really become clear until people began to use them widely. In this chapter we explain what we’ve learned from seeing these features in the real world, beyond what the manuals and reference material have taught us.

Partitioned Tables

A partitioned table is a single logical table that’s composed of multiple physical sub-tables. The partitioning code is really just a wrapper around a set of Handler objects that represent the underlying partitions, and it forwards requests to the storage engine through the Handler objects. Partitioning is a kind of black box that hides the underlying partitions from you at the SQL layer, although you can see them quite easily by looking at the filesystem, where you’ll see the component tables with a hash-delimited naming convention.

The way MySQL implements partitioning—as a wrapper over hidden tables—means that indexes are defined per-partition, rather than being created over the entire table. This is different from Oracle, for example, where indexes and tables can be partitioned in more flexible and complex ways.

MySQL decides which partition holds each row of data based on the PARTITION BY clause that you define for the table. The query optimizer can prune partitions when you execute queries, so the queries don’t examine all partitions—just the ones that hold the data you are looking for.

The primary purpose of partitioning is to act as a coarse form of indexing and data clustering over the table. This can help to eliminate large parts of the table from being accessed, and to store related rows close together.

Partitioning can be very beneficial, especially in specific scenarios:

§ When the table is much too big to fit in memory, or when you have “hot” rows at the end of a table that has lots of historical data.

§ Partitioned data is easier to maintain than nonpartitioned data. For example, it’s easier to discard old data by dropping an entire partition, which you can do quickly. You can also optimize, check, and repair individual partitions.

§ Partitioned data can be distributed physically, enabling the server to use multiple hard drives more efficiently.

§ You can use partitioning to avoid some bottlenecks in specific workloads, such as per-index mutexes with InnoDB or per-inode locking with the ext3 filesystem.

§ If you really need to, you can back up and restore individual partitions, which is very helpful with extremely large datasets.

MySQL’s implementation of partitioning is too complicated to explore in full detail here. We want to concentrate on its performance implications, so we recommend that for the basics you turn to the MySQL manual, which has a lot of material on partitioning. You should read the entire partitioning chapter, and look at the sections on CREATE TABLE, SHOW CREATE TABLE, ALTER TABLE, the INFORMATION_SCHEMA.PARTITIONS table, and EXPLAIN. Partitioning has made the CREATE TABLE and ALTER TABLE commands much more complex.

A few limitations apply to partitioned tables. Here are the most important ones:

§ There’s a limit of 1,024 partitions per table.

§ In MySQL 5.1, the partitioning expression must be an integer or an expression that returns an integer. In MySQL 5.5, you can partition by columns in certain cases.

§ Any primary key or unique index must include all columns in the partitioning expression.

§ You can’t use foreign key constraints.

How Partitioning Works

As we’ve mentioned, partitioned tables have multiple underlying tables, which are represented by Handler objects. You can’t access the partitions directly. Each partition is managed by the storage engine in the normal fashion (all partitions must use the same storage engine), and any indexes defined over the table are actually implemented as identical indexes over each underlying partition. From the storage engine’s point of view, the partitions are just tables; the storage engine doesn’t really know whether a specific table it’s managing is a standalone table or just part of a bigger partitioned table.

Operations on a partitioned table are implemented with the following logical operations:

SELECT queries

When you query a partitioned table, the partitioning layer opens and locks all of the underlying partitions, the query optimizer determines whether any of the partitions can be ignored (pruned), and then the partitioning layer forwards the handler API calls to the storage engine that manages the partitions.

INSERT queries

When you insert a row, the partitioning layer opens and locks all partitions, determines which partition should receive the row, and forwards the row to that partition.

DELETE queries

When you delete a row, the partitioning layer opens and locks all partitions, determines which partition contains the row, and forwards the deletion request to that partition.

UPDATE queries

When you modify a row, the partitioning layer (you guessed it) opens and locks all partitions, determines which partition contains the row, fetches the row, modifies the row and determines which partition should contain the new row, forwards the row with an insertion request to the destination partition, and forwards the deletion request to the source partition.

Some of these operations support pruning. For example, when you delete a row, the server first has to locate it. The server can prune partitions that can’t contain the row if you specify a WHERE clause that matches the partitioning expression. The same applies to UPDATE queries. INSERTqueries are naturally self-pruned; the server looks at the values to be inserted and finds one and only one destination partition.

Although the partitioning layer opens and locks all partitions, this doesn’t mean that the partitions remain locked. A storage engine such as InnoDB, which handles its own locking at the row level, will instruct the partitioning layer to unlock the partitions. This lock-and-unlock cycle is similar to how queries against ordinary InnoDB tables are executed.

We’ll show some examples a bit later that illustrate the cost and consequences of opening and locking every partition when there’s any access to the table.

Types of Partitioning

MySQL supports several types of partitioning. The most common type we’ve seen used is range partitioning, in which each partition is defined to accept a specific range of values for some column or columns, or a function over those columns. For example, here’s a simple way to place each year’s worth of sales into a separate partition:

CREATE TABLE sales (

order_date DATETIME NOT NULL,

-- Other columns omitted

) ENGINE=InnoDB PARTITION BY RANGE(YEAR(order_date)) (

PARTITION p_2010 VALUES LESS THAN (2010),

PARTITION p_2011 VALUES LESS THAN (2011),

PARTITION p_2012 VALUES LESS THAN (2012),

PARTITION p_catchall VALUES LESS THAN MAXVALUE );

You can use many functions in the partitioning clause. The main requirement is that it must return a nonconstant, deterministic integer. We’re using YEAR() here, but you can also use other functions, such as TO_DAYS(). Partitioning by intervals of time is a common way to work with date-based data, so we’ll return to this example later and see how to optimize it to avoid some of the problems it can cause.

MySQL also supports key, hash, and list partitioning methods, some of which support subpartitions, which we’ve rarely seen used in production. In MySQL 5.5 you can use the RANGE COLUMNS partitioning type, so you can partition by date-based columns directly, without using a function to convert them to an integer. More on that later.

One use of subpartitions we’ve seen was to work around a per-index mutex inside InnoDB on a table designed similarly to our previous example. The partition for the most recent year was modified heavily, which caused a lot of contention on that mutex. Subpartitioning by hash helped chop the data into smaller pieces and alleviated the problem.

Other partitioning techniques we’ve seen include:

§ You can partition by key to help reduce contention on InnoDB mutexes.

§ You can partition by range using a modulo function to create a round-robin table that retains only a desired amount of data. For example, you can partition date-based data by day modulo 7, or simply by day of week, if you want to retain only the most recent days of data.

§ Suppose you have a table with an autoincrementing idprimary key, but you want to partition the data temporally so the “hot” recent data is clustered together. You can’t partition by a timestamp column unless you include it in the primary key, but that defeats the purpose of a primary key. You can partition by an expression such as HASH(id DIV 1000000), which creates a new partition for each million rows inserted. This achieves the goal without requiring you to change the primary key. It has the added benefit that you don’t need to constantly create partitions to hold new ranges of dates, as you’d need to do with range-based partitioning.

How to Use Partitioning

Imagine that you want to run queries over ranges of data from a really huge table that contains many years’ worth of historical metrics in time-series order. You want to run reports on the most recent month, which is about 100 million rows. In a few years this book will be out of date, but let’s pretend that you have hardware from 2012 and your table is 10 terabytes, so it’s much bigger than memory, and you have traditional hard drives, not flash (most SSDs aren’t big enough for this table yet). How can you query this table at all, let alone efficiently?

One thing is sure: you can’t scan the whole table every time you want to query it, because it’s too big. And you don’t want to use an index because of the maintenance cost and space consumption. Depending on the index, you could get a lot of fragmentation and poorly clustered data, which would cause death by a thousand cuts through random I/O. You can sometimes work around this for one or two indexes, but rarely for more. Only two workable options remain: your query must be a sequential scan over a portion of the table, or the desired portion of the table and index must fit entirely in memory.

It’s worth restating this: at very large sizes, B-Tree indexes don’t work. Unless the index covers the query completely, the server needs to look up the full rows in the table, and that causes random I/O a row at a time over a very large space, which will just kill query response times. The cost of maintaining the index (disk space, I/O operations) is also very high. Systems such as Infobright acknowledge this and throw B-Tree indexes out entirely, opting for something coarser-grained but less costly at scale, such as per-block metadata over large blocks of data.

This is what partitioning can accomplish, too. The key is to think about partitioning as a crude form of indexing that has very low overhead and gets you in the neighborhood of the data you want. From there, you can either scan the neighborhood sequentially, or fit the neighborhood in memory and index it. Partitioning has low overhead because there is no data structure that points to rows and must be updated—partitioning doesn’t identify data at the precision of rows, and has no data structure to speak of. Instead, it has an equation that says which partitions can contain which categories of rows.

Let’s look at the two strategies that work at large scale:

Scan the data, don’t index it

You can create tables without indexes and use partitioning as the only mechanism to navigate to the desired kind of rows. As long as you always use a WHERE clause that prunes the query to a small number of partitions, this can be good enough. You’ll need to do the math and decide whether your query response times will be acceptable, of course. The assumption here is that you’re not even trying to fit the data in memory; you assume that anything you query has to be read from disk, and that that data will be replaced soon by some other query, so caching is futile. This strategy is for when you have to access a lot of the table on a regular basis. A caveat: for reasons we’ll explain a bit later, you usually need to limit yourself to a couple of hundred partitions at most.

Index the data, and segregate hot data

If your data is mostly unused except for a “hot” portion, and you can partition so that the hot data is stored in a single partition that is small enough to fit in memory along with its indexes, you can add indexes and write queries to take advantage of them, just as you would with smaller tables.

This isn’t quite all you need to know, because MySQL’s implementation of partitioning has a few pitfalls that can bite. Let’s see what those are and how to avoid them.

What Can Go Wrong

The two partitioning strategies we just suggested are based on two key assumptions: that you can narrow the search by pruning partitions when you query, and that partitioning itself is not very costly. As it turns out, those assumptions are not always valid. Here are a few problems you might encounter:

NULLs can defeat pruning

Partitioning works in a funny way when the result of the partitioning function can be NULL: it treats the first partition as special. Suppose that you PARTITION BY RANGE YEAR(order_date), as in the example we gave earlier. Any row whose order_date is either NULL or not a valid date will be stored in the first partition you define.[92] Now suppose you write a query that ends as follows: WHERE order_date BETWEEN '2012-01-01' AND '2012-01-31'. MySQL will actually check two partitions, not one: it will look at the partition that stores orders from 2012, as well as the first partition in the table. It looks at the first partition because the YEAR() function can return NULL if it receives invalid input, and values that might match the range would be stored as NULL in the first partition. This affects other functions, such as TO_DAYS(), too.[93]

This can be expensive if your first partition is large, especially if you’re using the “scan, don’t index” strategy. Checking two partitions instead of one to find the rows is definitely undesirable. To avoid this, you can define a dummy first partition. That is, we could fix our earlier example by creating a partition such as PARTITION p_nulls VALUES LESS THAN (0). If you don’t put invalid data into your table, that partition will be empty, and although it’ll be checked, it’ll be fast because it’s empty.

This workaround is not necessary in MySQL 5.5, where you can partition by the column itself, instead of a function over the column: PARTITION BY RANGE COLUMNS(order_date). Our earlier example should use that syntax in MySQL 5.5.

Mismatched PARTITION BY and index

If you define an index that doesn’t match the partitioning clause, queries might not be prunable. Suppose you define an index on a and partition by b. Each partition will have its own index, and a lookup on this index will open and check each index tree in every partition. This could be quick if the non-leaf nodes of each index are resident in memory, but it is nevertheless more costly than skipping the index lookups completely. To avoid this problem, you should try to avoid indexing on nonpartitioned columns unless your queries will also include an expression that can help prune out partitions.

This sounds simple enough to avoid, but it can catch you by surprise. For example, suppose a partitioned table ends up being the second table in a join, and the index that’s used for the join isn’t part of the partition clause. Each row in the join will access and search every partition in the second table.

Selecting partitions can be costly

The various types of partitioning are implemented in different ways, so of course their performance is not uniform all the time. In particular, questions such as “Where does this row belong?” or “Where can I find rows matching this query?” can be costly to answer with range partitioning, because the server scans the list of partition definitions to find the right one. This linear search isn’t all that efficient, as it turns out, so the cost grows as the number of partitions grows.

The queries we’ve observed to suffer the worst from this type of overhead are row-by-row inserts. For every row you insert into a table that’s partitioned by range, the server has to scan the list of partitions to select the destination. You can alleviate this problem by limiting how many partitions you define. In practice, a hundred or so works okay for most systems we’ve seen.

Other partition types, such as key and hash partitions, don’t have the same limitation.

Opening and locking partitions can be costly

Opening and locking partitions when a query accesses a partitioned table is another type of per-partition overhead. Opening and locking occur before pruning, so this isn’t a prunable overhead. This type of overhead is independent of the partitioning type and affects all types of statements. It adds an especially noticeable amount of overhead to short operations, such as single-row lookups by primary key. You can avoid high per-statement costs by performing operations in bulk, such as using multirow inserts or LOAD DATA INFILE, deleting ranges of rows instead of one at a time, and so on. And, of course, limit the number of partitions you define.

Maintenance operations can be costly

Some partition maintenance operations are very quick, such as creating or dropping partitions. (Dropping the underlying table might be slow, but that’s another matter.) Other operations, such as REORGANIZE PARTITION, operate similarly to the way ALTER works: by copying rows around. For example, REORGANIZE PARTITION works by creating a new temporary partition, moving rows into it, and deleting the old partition when it’s done.

As you can see, partitioned tables are not a “silver bullet” solution. Here is a sample of some other limitations in the current implementation:

§ All partitions have to use the same storage engine.

§ There are some restrictions on the functions and expressions you can use in a partitioning function.

§ Some storage engines don’t work with partitioning.

§ For MyISAM tables, you can’t use LOAD INDEX INTO CACHE.

§ For MyISAM tables, a partitioned table requires more open file descriptors than a normal table containing the same data. Even though it looks like a single table, as you know, it’s really many tables. As a result, a single table cache entry can create many file descriptors. Therefore, even if you have configured the table cache to protect your server against exceeding the operating system’s per-process file-descriptor limits, partitioned tables can cause you to exceed that limit anyway.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that older server versions just aren’t as good as newer ones. All software has bugs. Partitioning was introduced in MySQL 5.1, and many partitioning bugs were fixed as late as the 5.1.40s and 5.1.50s. MySQL 5.5 improved partitioning significantly in some common real-world cases. In the upcoming MySQL 5.6 release, there are more improvements, such as ALTER TABLE EXCHANGE PARTITION.

Optimizing Queries

Partitioning introduces new ways to optimize queries (and corresponding pitfalls). The biggest opportunity is that the optimizer can use the partitioning function to prune partitions. As you’d expect from a coarse-grained index, pruning lets queries access much less data than they’d otherwise need to (in the best case).

Thus, it’s very important to specify the partitioned key in the WHERE clause, even if it’s otherwise redundant, so the optimizer can prune unneeded partitions. If you don’t do this, the query execution engine will have to access all partitions in the table, and this can be extremely slow on large tables.

You can use EXPLAIN PARTITIONS to see whether the optimizer is pruning partitions. Let’s return to the sample data from before:

mysql> EXPLAIN PARTITIONS SELECT * FROM sales \G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

id: 1

select_type: SIMPLE

table: sales_by_day

partitions: p_2010,p_2011,p_2012

type: ALL

possible_keys: NULL

key: NULL

key_len: NULL

ref: NULL

rows: 3

Extra:

As you can see, the query will access all partitions. Look at the difference when we add a constraint to the WHERE clause:

mysql> EXPLAIN PARTITIONS SELECT * FROM sales_by_day WHERE day > '2011-01-01'\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

id: 1

select_type: SIMPLE

table: sales_by_day

partitions: p_2011,p_2012

The optimizer is pretty good about pruning; for example, it can convert ranges into lists of discrete values and prune on each item in the list. However, it’s not all-knowing. The following WHERE clause is theoretically prunable, but MySQL can’t prune it:

mysql> EXPLAIN PARTITIONS SELECT * FROM sales_by_day WHERE YEAR(day) = 2010\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

id: 1

select_type: SIMPLE

table: sales_by_day

partitions: p_2010,p_2011,p_2012

MySQL can prune only on comparisons to the partitioning function’s columns. It cannot prune on the result of an expression, even if the expression is the same as the partitioning function. This is similar to the way that indexed columns must be isolated in the query to make the index usable (see Chapter 5). You can convert the query into an equivalent form, though:

mysql> EXPLAIN PARTITIONS SELECT * FROM sales_by_day

-> WHERE day BETWEEN '2010-01-01' AND '2010-12-31'\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

id: 1

select_type: SIMPLE

table: sales_by_day

partitions: p_2010

Because the WHERE clause now refers directly to the partitioning column, not to an expression, the optimizer can prune out other partitions. The rule of thumb is that even though you can partition by expressions, you must search by column.

The optimizer is smart enough to prune partitions during query processing, too. For example, if a partitioned table is the second table in a join, and the join condition is the partitioned key, MySQL will search for matching rows only in the relevant partitions. (EXPLAIN won’t show the partition pruning, because it happens at runtime, not at query optimization time.)

Merge Tables

Merge tables are sort of an earlier, simpler kind of partitioning with different restrictions and fewer optimizations. Whereas partitioning enforces the abstraction rigorously, denying access to the underlying partitions and permitting you to reference only the partitioned table, merge tables let you access the underlying tables separately from the merge table. And whereas partitioning is more integrated with the query optimizer and is the way of the future, merge tables are quasi-deprecated and might even be removed someday.

Like partitioned tables, merge tables are wrappers around underlying MyISAM tables with the same structure. Although you can think of merge tables as an older, more limited version of partitioning, they actually provide some features you can’t get with partitions.[94]

The merge table is really just a container that holds the real tables. You specify which tables to include with a special UNION syntax to CREATE TABLE. Here’s an example that demonstrates many aspects of merge tables:

mysql> CREATE TABLE t1(a INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY)ENGINE=MyISAM;

mysql> CREATE TABLE t2(a INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY)ENGINE=MyISAM;

mysql> INSERT INTO t1(a) VALUES(1),(2);

mysql> INSERT INTO t2(a) VALUES(1),(2);

mysql> CREATE TABLE mrg(a INT NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY)

-> ENGINE=MERGE UNION=(t1, t2) INSERT_METHOD=LAST;

mysql> SELECT a FROM mrg;

+------+

| a |

+------+

| 1 |

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 2 |

+------+

Notice that the underlying tables have exactly the same number and types of columns, and that all indexes that exist on the merge table also exist on the underlying tables. These are requirements when creating a merge table. Notice also that there’s a primary key on the sole column of each table, yet the resulting merge table has duplicate rows. This is one of the limitations of merge tables: each table inside the merge behaves normally, but the merge table doesn’t enforce constraints over the entire set of tables.

The INSERT_METHOD=LAST instruction to the table tells MySQL to send all INSERT statements to the last table in the merge. Specifying FIRST or LAST is the only control you have over where rows inserted into the merge table are placed (you can still insert into the underlying tables directly, though). Partitioned tables give more control over where data is stored.

The results of an INSERT are visible in both the merge table and the underlying table:

mysql> INSERT INTO mrg(a) VALUES(3);

mysql> SELECT a FROM t2;

+---+

| a |

+---+

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

+---+

Merge tables have some other interesting features and limitations, such as what happens when you drop a merge table or one of its underlying tables. Dropping a merge table leaves its “child” tables untouched, but dropping one of the child tables has a different effect, which is operating system–specific. On GNU/Linux, for example, the underlying table’s file descriptor stays open and the table continues to exist, but only via the merge table:

mysql> DROP TABLE t1, t2;

mysql> SELECT a FROM mrg;

+------+

| a |

+------+

| 1 |

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

+------+

A variety of other limitations and special behaviors exist. Here are some aspects of merge tables you should keep in mind:

§ The CREATE statement that creates a merge table doesn’t check that the underlying tables are compatible. If the underlying tables are defined slightly differently, MySQL might create a merge table that it can’t use later. Also, if you alter one of the underlying tables after creating a valid merge table, it will stop working and you’ll see this error: “ERROR 1168 (HY000): Unable to open underlying table which is differently defined or of non-MyISAM type or doesn’t exist.”

§ REPLACE doesn’t work at all on a merge table, and AUTO_INCREMENT won’t work as you might expect. We’ll let you read the manual for the details.

§ Queries that access a merge table access every underlying table. This can make single-row key lookups relatively slow, compared to a lookup in a single table. Therefore, it’s a good idea to limit the number of underlying tables in a merge table, especially if it is the second or later table in a join. The less data you access with each operation, the more important the cost of accessing each table becomes, relative to the entire operation. Here are a few things to keep in mind when planning how to use merge tables:

§ Range lookups are less affected by the overhead of accessing all the underlying tables than individual item lookups.

§ Table scans are just as fast on merge tables as they are on normal tables.

§ Unique key and primary key lookups stop as soon as they succeed. In this case, the server accesses the underlying merge tables one at a time until the lookup finds a value, and then it accesses no further tables.

§ The underlying tables are read in the order specified in the CREATE TABLE statement. If you frequently need data in a specific order, you can exploit this to make the merge-sorting operation faster.

Because merge tables don’t hide the underlying MyISAM tables, they offer some features that partitions don’t as of MySQL 5.5:

§ A MyISAM table can be a member of many merge tables.

§ You can copy underlying tables between servers by copying the .frm, .MYI, and .MYD files.

§ You can add more tables to a merge collection easily; just alter the merge definition.

§ You can create temporary merge tables that include only the data you want, such as data from a specific time period, which you can’t do with partitions.

§ You can remove a table from the merge if you want to back it up, restore it, alter it, repair it, or perform other operations on it. You can then add it back when you’re done.

§ You can use myisampack to compress some or all of the underlying tables.

In contrast, a partitioned table’s partitions are hidden by the MySQL server and are accessible only through the partitioned table.

[92] This happens even if order_date is not nullable, because you can store a value that’s not a valid date.

[93] This is a bug from the user’s point of view, but a feature from the server developer’s point of view.

[94] Some people call these features “foot-guns.”

Views

Views were added in MySQL 5.0. A view is a virtual table that doesn’t store any data itself. Instead, the data “in” the table is derived from a SQL query that MySQL runs when you access the view. MySQL treats a view exactly like a table for many purposes, and views and tables share the same namespace in MySQL; however, MySQL doesn’t treat them identically. For example, you can’t have triggers on views, and you can’t drop a view with the DROP TABLE command.

This book does not explain how to create or use views; you can read the MySQL manual for that. We’ll focus on how views are implemented and how they interact with the query optimizer, so you can understand how to get good performance from them. We use the world sample database to demonstrate how views work:

mysql> CREATE VIEW Oceania AS

-> SELECT * FROM Country WHERE Continent = 'Oceania'

-> WITH CHECK OPTION;

The easiest way for the server to implement a view is to execute its SELECT statement and place the result into a temporary table. It can then refer to the temporary table where the view’s name appears in the query. To see how this would work, consider the following query:

mysql> SELECT Code, Name FROM Oceania WHERE Name = 'Australia';

Here’s how the server might execute it as a temporary table. The temporary table’s name is for demonstration purposes only:

mysql> CREATE TEMPORARY TABLE TMP_Oceania_123 AS

-> SELECT * FROM Country WHERE Continent = 'Oceania';

mysql> SELECT Code, Name FROM TMP_Oceania_123 WHERE Name = 'Australia';

There are obvious performance and query optimization problems with this approach. A better way to implement views is to rewrite a query that refers to the view, merging the view’s SQL with the query’s SQL. The following example shows how the query might look after MySQL has merged it into the view definition:

mysql> SELECT Code, Name FROM Country

-> WHERE Continent = 'Oceania' AND Name = 'Australia';

MySQL can use both methods. It calls the two algorithms MERGE and TEMPTABLE,[95] and it tries to use the MERGE algorithm when possible. MySQL can even merge nested view definitions when a view is based upon another view. You can see the results of the query rewrite with EXPLAIN EXTENDED, followed by SHOW WARNINGS.

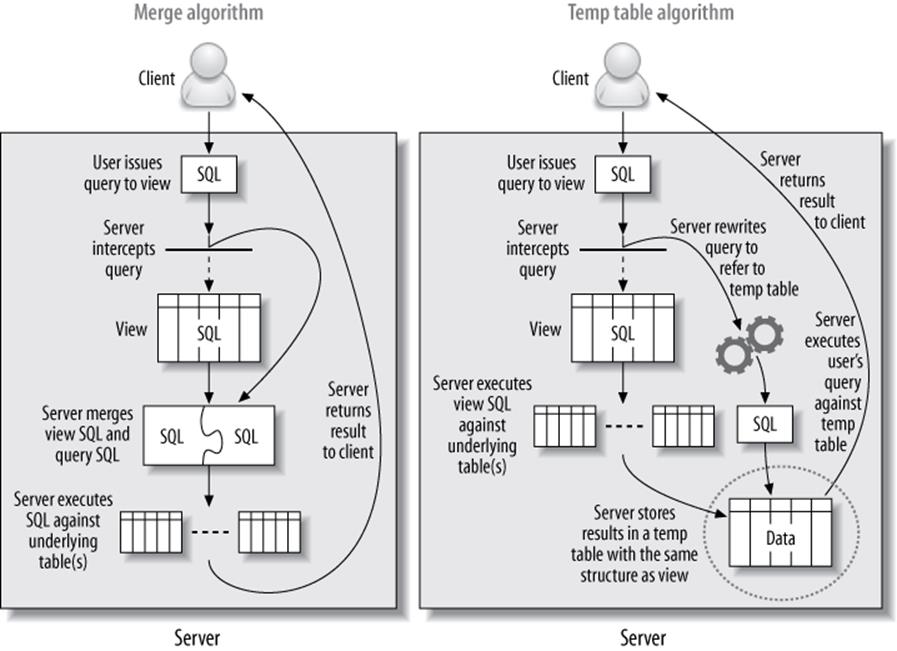

If a view uses the TEMPTABLE algorithm, EXPLAIN will usually show it as a DERIVED table. Figure 7-1 illustrates the two implementations.

Figure 7-1. Two implementations of views

MySQL uses TEMPTABLE when the view definition contains GROUP BY, DISTINCT, aggregate functions, UNION, subqueries, or any other construct that doesn’t preserve a one-to-one relationship between the rows in the underlying base tables and the rows returned from the view. This is not a complete list, and it might change in the future. If you want to know whether a view will use MERGE or TEMPTABLE, you can EXPLAIN a trivial SELECT query against the view:

mysql> EXPLAIN SELECT * FROM<view_name>;

+----+-------------+

| id | select_type |

+----+-------------+

| 1 | PRIMARY |

| 2 | DERIVED |

+----+-------------+

The presence of a SELECT type of DERIVED select type indicates that the view will use the TEMPTABLE algorithm. Beware, though: if the underlying derived table is expensive to produce, EXPLAIN can be quite costly and slow to execute in MySQL 5.5 and older versions, because it will actually execute and materialize the derived table.

The algorithm is a property of the view and is not influenced by the type of query that is executed against the view. For example, suppose you create a trivial view and explicitly specify the TEMPTABLE algorithm:

CREATE ALGORITHM=TEMPTABLE VIEW v1 AS SELECT * FROM sakila.actor;

The SQL inside the view doesn’t inherently require a temporary table, but the view will always use one, no matter what type of query you execute against it.

Updatable Views

An updatable view lets you update the underlying base tables via the view. As long as specific conditions hold, you can UPDATE, DELETE, and even INSERT into a view as you would with a normal table. For example, the following is a valid operation:

mysql> UPDATE Oceania SET Population = Population * 1.1 WHERE Name = 'Australia';

A view is not updatable if it contains GROUP BY, UNION, an aggregate function, or any of a few other exceptions. A query that changes data might contain a join, but the columns to be changed must all be in a single table. Any view that uses the TEMPTABLE algorithm is not updatable.

The CHECK OPTION clause, which we included when we created the view in the previous section, ensures that any rows changed through the view continue to match the view’s WHERE clause after the change. So, we can’t change the Continent column, nor can we insert a row that has a different Continent. Either would cause the server to report an error:

mysql> UPDATE Oceania SET Continent = 'Atlantis';

ERROR 1369 (HY000): CHECK OPTION failed 'world.Oceania'

Some database products allow INSTEAD OF triggers on views so you can define exactly what happens when a statement tries to modify a view’s data, but MySQL does not support triggers on views.

Performance Implications of Views

Most people don’t think of using views to improve performance, but in some cases they can actually enhance performance in MySQL. You can also use them to aid other performance improvements. For example, refactoring a schema in stages with views can let some code continue working while you change the tables it accesses.

You can use views to implement column privileges without the overhead of actually creating those privileges:

CREATE VIEW public.employeeinfo AS

SELECT firstname, lastname -- but not socialsecuritynumber

FROM private.employeeinfo;

GRANT SELECT ON public.* TO public_user;

You can also sometimes use pseudotemporary views to good effect. You can’t actually create a truly temporary view that persists only for your current connection, but you can create a view under a special name, perhaps in a database reserved for it, that you know you can drop later. You can then use the view in the FROM clause, much the same way you’d use a subquery in the FROM clause. The two approaches are theoretically the same, but MySQL has a different codebase for views, so performance can vary. Here’s an example:

-- Assuming 1234 is the result of CONNECTION_ID()

CREATE VIEW temp.cost_per_day_1234 AS

SELECT DATE(ts) AS day, sum(cost) AS cost

FROM logs.cost

GROUP BY day;

SELECT c.day, c.cost, s.sales

FROM temp.cost_per_day_1234 AS c

INNER JOIN sales.sales_per_day AS s USING(day);

DROP VIEW temp.cost_per_day_1234;

Note that we’ve used the connection ID as a unique suffix to avoid name clashes. This approach can make it easier to clean up in the event that the application crashes and doesn’t drop the temporary view. See Missing Temporary Tables for more about this technique.

Views that use the TEMPTABLE algorithm can perform very badly (although they might still perform better than an equivalent query that doesn’t use a view). MySQL executes them as a recursive step in optimizing the outer query, before the outer query is even fully optimized, so they don’t get a lot of the optimizations you might be used to from other database products. The query that builds the temporary table doesn’t get WHERE conditions pushed down from the outer query, and the temporary table does not have any indexes.[96] Here’s an example, again using thetemp.cost_per_day_1234 view:

mysql> SELECT c.day, c.cost, s.sales

-> FROM temp.cost_per_day_1234 AS c

-> INNER JOIN sales.sales_per_day AS s USING(day)

-> WHERE day BETWEEN '2007-01-01' AND '2007-01-31';

What really happens in this query is that the server executes the view and places the result into a temporary table, then joins the sales_per_day table against this temporary table. The BETWEEN restriction in the WHERE clause is not “pushed into” the view, so the view will create a result set for all dates in the table, not just the one month desired. The temporary table also lacks any indexes. In this example, this isn’t a problem: the server will place the temporary table first in the join order, so the join can use the index on the sales_per_day table. However, if we were joining two such views against each other, the join would not be optimized with any indexes.

Views introduce some issues that aren’t MySQL-specific. Views might trick developers into thinking they’re simple, when in fact they’re very complicated under the hood. A developer who doesn’t understand the underlying complexity might think nothing of repeatedly querying what looks like a table but is in fact an expensive view. We’ve seen cases where an apparently simple query produced hundreds of lines of EXPLAIN output because one or more of the “tables” it referenced was actually a view that referred to many other tables and views.

You should always measure carefully if you’re trying to use views to improve performance. Even MERGE views add overhead, and it’s hard to predict how a view will impact performance. Views actually use a different execution path within the MySQL optimizer, one that isn’t tested as widely and might still have bugs or problems. For that reason, views don’t seem quite as mature as we’d like. For example, we’ve seen cases where complex views under high concurrency caused the query optimizer to spend a lot of time in the planning and statistics stages of the query, even causing server-wide stalls, which we solved by replacing the view with the equivalent SQL. This indicates that views—even those using the MERGE algorithm—don’t always have an optimal implementation.

Limitations of Views

MySQL does not support the materialized views that you might be used to if you’ve worked with other database servers. (A materialized view generally stores its results in an invisible table behind the scenes, with periodic updates to refresh the invisible table from the source data.) MySQL also doesn’t support indexed views. You can emulate materialized and/or indexed views by building cache and summary tables, however. You use Justin Swanhart’s Flexviews tool for this purpose; see Chapter 4 for more.

MySQL’s implementation of views also has a few annoyances. For example, MySQL doesn’t preserve your original view SQL, so if you ever try to edit a view by executing SHOW CREATE VIEW and changing the resulting SQL, you’re in for a nasty surprise. The query will be expanded to the fully canonicalized and quoted internal format, without the benefit of formatting, comments, and indenting.

If you need to edit a view and you’ve lost the pretty-printed query you originally used to create it, you can find it in the last line of the view’s .frm file. If you have the FILE privilege and the .frm file is readable by all users, you can even load the file’s contents through SQL with theLOAD_FILE() function. A little string manipulation can retrieve your original code intact, thanks to Roland Bouman’s creativity:

mysql> SELECT

-> REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(

-> REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(REPLACE(

-> SUBSTRING_INDEX(LOAD_FILE('/var/lib/mysql/world/Oceania.frm'),

-> '\nsource=', −1),

-> '\\_','\_'), '\\%','\%'), '\\\\','\\'), '\\Z','\Z'), '\\t','\t'),

-> '\\r','\r'), '\\n','\n'), '\\b','\b'), '\\\"','\"'), '\\\'','\''),

-> '\\0','\0')

-> AS source;

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| source |

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| SELECT * FROM Country WHERE continent = 'Oceania'

WITH CHECK OPTION

|

+-------------------------------------------------------------------------+

[95] That’s “temp table,” not “can be tempted.” MySQL’s views don’t fast for 40 days and nights in the wilderness, either.

[96] This will be improved in MySQL 5.6, which is unreleased at the time of writing.

Foreign Key Constraints

InnoDB is currently the only bundled storage engine that supports foreign keys in MySQL, limiting your choice of storage engines if you require them (PBXT has foreign keys, too).

Foreign keys aren’t free. They typically require the server to do a lookup in another table every time you change some data. Although InnoDB requires an index to make this operation faster, this doesn’t eliminate the impact of these checks. It can even result in a very large index with virtually zero selectivity. For example, suppose you have a status column in a huge table and you want to constrain the status to valid values, but there are only three such values. The extra index required can add significantly to the table’s total size—even if the column itself is small, and especially if the primary key is large—and is useless for anything but the foreign key checks.

Still, foreign keys can actually improve performance in some cases. If you must guarantee that two related tables have consistent data, it can be more efficient to let the server perform this check than to do it in your application. Foreign keys are also useful for cascading deletes or updates, although they do operate row by row, so they’re slower than multitable deletes or batch operations.

Foreign keys cause your query to “reach into” other tables, which means acquiring locks. If you insert a row into a child table, for example, the foreign key constraint will cause InnoDB to check for a corresponding value in the parent. It must also lock the row in the parent, to ensure it doesn’t get deleted before the transaction completes. This can cause unexpected lock waits and even deadlocks on tables you’re not touching directly. Such problems can be very unintuitive and frustrating to debug.

You can sometimes use triggers instead of foreign keys. Foreign keys tend to outperform triggers for tasks such as cascading updates, but a foreign key that’s just used as a constraint, as in our status example, can be more efficiently rewritten as a trigger with an explicit list of allowable values. (You can also just use an ENUM data type.)

Instead of using foreign keys as constraints, it’s often a good idea to constrain the values in the application. Foreign keys can add significant overhead. We don’t have any benchmarks to share, but we have seen many cases where server profiling revealed that foreign key constraint checks were the performance problem, and removing the foreign keys improved performance greatly.

Storing Code Inside MySQL

MySQL lets you store code inside the server in the form of triggers, stored procedures, and stored functions. In MySQL 5.1, you can also store code in periodic jobs called events. Stored procedures and stored functions are collectively known as “stored routines.”

All four types of stored code use a special extended SQL language that contains procedural structures such as loops and conditionals.[97] The biggest difference between the types of stored code is the context in which they operate—that is, their inputs and outputs. Stored procedures and stored functions can accept parameters and return results, but triggers and events do not.

In principle, stored code is a good way to share and reuse code. Giuseppe Maxia and others have created a library of useful general-purpose stored routines at http://mysql-sr-lib.sourceforge.net. However, it’s hard to reuse stored routines from other database systems, because most have their own language (the exception is DB2, which has a fairly similar language based on the same standard).[98]

We focus more on the performance implications of stored code than on how to write it. Guy Harrison and Steven Feuerstein’s MySQL Stored Procedure Programming (O’Reilly) might be useful if you plan to write stored procedures in MySQL.

It’s easy to find both advocates and opponents of stored code. Without taking sides, we’ll list some of the pros and cons of using it in MySQL. First, the advantages:

§ It runs where the data is, so you can save bandwidth and reduce latency by running tasks on the database server.

§ It’s a form of code reuse. It can help centralize business rules, which can enforce consistent behavior and provide more safety and peace of mind.

§ It can ease release policies and maintenance.

§ It can provide some security advantages and a way to control privileges more finely. A common example is a stored procedure for funds transfer at a bank: the procedure transfers the money within a transaction and logs the entire operation for auditing. You can let applications call the stored procedure without granting access to the underlying tables.

§ The server caches stored procedure execution plans, which lowers the overhead of repeated calls.

§ Because it’s stored in the server and can be deployed, backed up, and maintained with the server, stored code is well suited for maintenance jobs. It doesn’t have any external dependencies, such as Perl libraries or other software that you might not want to place on the server.

§ It enables division of labor between application programmers and database programmers. It can be preferable for a database expert to write the stored procedures, as not every application programmer is good at writing efficient SQL queries.

Disadvantages include the following:

§ MySQL doesn’t provide good developing and debugging tools, so it’s harder to write stored code in MySQL than it is in some other database servers.

§ The language is slow and primitive compared to application languages. The number of functions you can use is limited, and it’s hard to do complex string manipulations and write intricate logic.

§ Stored code can actually add complexity to deploying your application. Instead of just application code and database schema changes, you’ll need to deploy code that’s stored inside the server, too.

§ Because stored routines are stored with the database, they can create a security vulnerability. Having nonstandard cryptographic functions inside a stored routine, for example, will not protect your data if the database is compromised. If the cryptographic function were in the code, the attacker would have to compromise both the code and the database.

§ Storing routines moves the load to the database server, which is typically harder to scale and more expensive than application or web servers.

§ MySQL doesn’t give you much control over the resources stored code can allocate, so a mistake can bring down the server.

§ MySQL’s implementation of stored code is pretty limited—execution plan caches are per-connection, cursors are materialized as temporary tables, there’s very limited ability to raise and catch errors prior to MySQL 5.5, and so on. (We mention the limitations of various features as we describe them.) In general, MySQL’s stored routine language is nowhere near as capable as T-SQL or PL/SQL.

§ It’s hard to profile code with stored procedures in MySQL. It’s difficult to analyze the slow query log when it just shows CALL XYZ('A'), because you have to go and find that procedure and look at the statements inside it. (This is configurable in Percona Server.)

§ It doesn’t play well with statement-based binary logging or replication. There are so many “gotchas” that you probably should not use stored code with statement-based logging unless you are very knowledgeable and strict about checking it for potential problems.

That’s a long list of drawbacks—what does this all mean in the real world? Here’s an example where we’ve seen the use of stored code backfire in real life: in one instance, using them to create an API for the application to access the database. This resulted in all access to the database—even trivial primary-key row lookups—going through CALL queries, which reduced performance by about a factor of five.

Ultimately, stored code is a way to hide complexity, which simplifies development but can be very bad for performance and add a lot of potential hazards with replication and other server features. When you’re thinking about using stored code, you should ask yourself where you want your business logic to live: in application code, or in the database? Both approaches are popular. You just need to be aware that you’re placing logic into the database when you use stored code.

Stored Procedures and Functions

MySQL’s architecture and query optimizer place some limits on how you can use stored routines and how efficient they can be. The following restrictions apply at the time of this writing:

§ The optimizer doesn’t use the DETERMINISTIC modifier in stored functions to optimize away multiple calls within a single query.

§ The optimizer cannot estimate how much it will cost to execute a stored function.

§ Each connection has its own stored procedure execution plan cache. If many connections call the same procedure, they’ll waste resources caching the same execution plan over and over. (If you use connection pooling or persistent connections, the execution plan cache can have a longer useful life.)

§ Stored routines and replication are a tricky combination. You might not want to replicate the call to the routine. Instead, you might want to replicate the exact changes made to your dataset. Row-based replication, introduced in MySQL 5.1, helps alleviate this problem. If binary logging is enabled in MySQL 5.0, the server will insist that you either define all stored procedures as DETERMINISTIC or enable the elaborately named server option log_bin_trust_function_creators.

We usually prefer to keep stored routines small and simple. We like to perform complex logic outside the database in a procedural language, which is more expressive and versatile. It can also give you access to more computational resources and potentially to different forms of caching.

However, stored procedures can be much faster for certain types of operations—especially when a single stored procedure call with a loop inside it can replace many small queries. If a query is small enough, the overhead of parsing and network communication becomes a significant fraction of the overall work required to execute it. To illustrate this, we created a simple stored procedure that inserts a specified number of rows into a table. Here’s the procedure’s code:

1 DROP PROCEDURE IF EXISTS insert_many_rows;

2

3 delimiter //

4

5 CREATE PROCEDURE insert_many_rows (IN loops INT)

6 BEGIN

7 DECLARE v1 INT;

8 SET v1=loops;

9 WHILE v1 > 0 DO

10 INSERT INTO test_table values(NULL,0,

11 'qqqqqqqqqqwwwwwwwwwweeeeeeeeeerrrrrrrrrrtttttttttt',

12 'qqqqqqqqqqwwwwwwwwwweeeeeeeeeerrrrrrrrrrtttttttttt');

13 SET v1 = v1 - 1;

14 END WHILE;

15 END;

16 //

17

18 delimiter ;

We then benchmarked how quickly this stored procedure could insert a million rows into a table, as compared to inserting one row at a time via a client application. The table structure and hardware we used doesn’t really matter—what is important is the relative speed of the different approaches. Just for fun, we also measured how long the same queries took to execute when we connected through a MySQL Proxy. To keep things simple, we ran the entire benchmark on a single server, including the client application and the MySQL Proxy instance. Table 7-1 shows the results.

Table 7-1. Total time to insert one million rows one at a time

|

Method |

Total time |

|

Stored procedure |

101 sec |

|

Client application |

279 sec |

|

Client application with MySQL Proxy |

307 sec |

The stored procedure is much faster, mostly because it avoids the overhead of network communication, parsing, optimizing, and so on.

We show a typical stored procedure for maintenance jobs later in this chapter.

Triggers

Triggers let you execute code when there’s an INSERT, UPDATE, or DELETE statement. You can direct MySQL to activate triggers before and/or after the triggering statement executes. They cannot return values, but they can read and/or change the data that the triggering statement changes. Thus, you can use triggers to enforce constraints or business logic that you’d otherwise need to write in client code.

Triggers can simplify application logic and improve performance, because they save round-trips between the client and the server. They can also be helpful for automatically updating denormalized and summary tables. For example, the Sakila sample database uses them to maintain thefilm_text table.

MySQL’s trigger implementation is very limited. If you’re used to relying on triggers extensively in another database product, you shouldn’t assume they will work the same way in MySQL. In particular:

§ You can have only one trigger per table for each event (in other words, you can’t have two triggers that fire AFTER INSERT).

§ MySQL supports only row-level triggers—that is, triggers always operate FOR EACH ROW rather than for the statement as a whole. This is a much less efficient way to process large datasets.

The following universal cautions about triggers apply in MySQL, too:

§ They can obscure what your server is really doing, because a simple statement can make the server perform a lot of “invisible” work. For example, if a trigger updates a related table, it can double the number of rows a statement affects.

§ Triggers can be hard to debug, and it’s often difficult to analyze performance bottlenecks when triggers are involved.

§ Triggers can cause nonobvious deadlocks and lock waits. If a trigger fails the original query will fail, and if you’re not aware the trigger exists, it can be hard to decipher the error code.

In terms of performance, the most severe limitation in MySQL’s trigger implementation is the FOR EACH ROW design. This sometimes makes it impractical to use triggers for maintaining summary and cache tables, because they might be too slow. The main reason to use triggers instead of a periodic bulk update is that they keep your data consistent at all times.

Triggers also might not guarantee atomicity. For example, a trigger that updates a MyISAM table cannot be rolled back if there’s an error in the statement that fires it. It is possible for a trigger to cause an error, too. Suppose you attach an AFTER UPDATE trigger to a MyISAM table and use it to update another MyISAM table. If the trigger has an error that causes the second table’s update to fail, the first table’s update will not be rolled back.

Triggers on InnoDB tables all operate within the same transaction, so the actions they take will be atomic, together with the statement that fired them. However, if you’re using a trigger with InnoDB to check another table’s data when validating a constraint, be careful about MVCC, as you can get incorrect results if you’re not careful. For example, suppose you want to emulate foreign keys, but you don’t want to use InnoDB’s foreign keys. You can write a BEFORE INSERT trigger that verifies the existence of a matching record in another table, but if you don’t use SELECT FOR UPDATE in the trigger when reading from the other table, concurrent updates to that table can cause incorrect results.

We don’t mean to scare you away from triggers. On the contrary, they can be useful, particularly for constraints, system maintenance tasks, and keeping denormalized data up-to-date.

You can also use triggers to log changes to rows. This can be handy for custom-built replication setups where you want to disconnect systems, make data changes, and then merge the changes back together. A simple example is a group of users who take laptops onto a job site. Their changes need to be synchronized to a master database, and then the master data needs to be copied back to the individual laptops. Accomplishing this requires two-way synchronization. Triggers are a good way to build such systems. Each laptop can use triggers to log every data modification to tables that indicate which rows have been changed. The custom synchronization tool can then apply these changes to the master database. Finally, ordinary MySQL replication can sync the laptops with the master, which will have the changes from all the laptops. However, you need to be very careful with triggers that insert rows into other tables that have autoincrementing primary keys. This doesn’t play well with statement-based replication, as the autoincrement values are likely to be different on replicas.

Sometimes you can work around the FOR EACH ROW limitation. Roland Bouman found that ROW_COUNT() always reports 1 inside a trigger, except for the first row of a BEFORE trigger. You can use this to prevent a trigger’s code from executing for every row affected and run it only once per statement. It’s not the same as a per-statement trigger, but it is a useful technique for emulating a per-statement BEFORE trigger in some cases. This behavior might actually be a bug that will get fixed at some point, so you should use it with care and verify that it still works when you upgrade your server. Here’s a sample of how to use this hack:

CREATE TRIGGER fake_statement_trigger

BEFORE INSERT ON sometable

FOR EACH ROW

BEGIN

DECLARE v_row_count INT DEFAULT ROW_COUNT();

IF v_row_count <> 1 THEN

-- Your code here

END IF;

END;

Events

Events are a new form of stored code in MySQL 5.1. They are akin to cron jobs but are completely internal to the MySQL server. You can create events that execute SQL code once at a specific time, or frequently at a specified interval. The usual practice is to wrap the complex SQL in a stored procedure, so the event merely needs to perform a CALL.

Events are initiated by a separate event scheduler thread, because they have nothing to do with connections. They accept no inputs and return no values—there’s no connection for them to get inputs from or return values to. You can see the commands they execute in the server log, if it’s enabled, but it can be hard to tell that those commands were executed from an event. You can also look in the INFORMATION_SCHEMA.EVENTS table to see an event’s status, such as the last time it was executed.

Similar considerations to those that apply to stored procedures apply to events. First, you are giving the server additional work to do. The event overhead itself is minimal, but the SQL it calls can have a potentially serious impact on performance. Further, events can cause the same types of problems with statement-based replication that other stored code can cause. Good uses for events include periodic maintenance tasks, rebuilding cache and summary tables to emulate materialized views, or saving status values for monitoring and diagnostics.

The following example creates an event that will run a stored procedure for a specific database, once a week (we’ll show you how to create this stored procedure later):

CREATE EVENT optimize_somedb ON SCHEDULE EVERY 1 WEEK

DO

CALL optimize_tables('somedb');

You can specify whether events should be replicated. In some cases this is appropriate, whereas in others it’s not. Take the previous example, for instance: you probably want to run the OPTIMIZE TABLE operation on all replicas, but keep in mind that it could impact overall server performance (with table locks, for instance) if all replicas were to execute this operation at the same time.

Finally, if a periodic event can take a long time to complete, it might be possible for the event to fire again while its earlier execution is still running. MySQL doesn’t protect against this, so you’ll have to write your own mutual exclusivity code. You can use GET_LOCK() to make sure that only one event runs at a time:

CREATE EVENT optimize_somedb ON SCHEDULE EVERY 1 WEEK

DO

BEGIN

DECLARE CONTINUE HANLDER FOR SQLEXCEPTION

BEGIN END;

IF GET_LOCK('somedb', 0) THEN

DO CALL optimize_tables('somedb');

END IF;

DO RELEASE_LOCK('somedb');

END

The “dummy” continue handler ensures that the event will release the lock, even if the stored procedure throws an exception.

Although events are dissociated from connections, they are still associated with threads. There’s a main event scheduler thread, which you must enable in your server’s configuration file or with a SET command:

mysql> SET GLOBAL event_scheduler := 1;

When enabled, this thread executes events on the schedule specified in the event. You can watch the server’s error log for information about event execution.

Although the event scheduler is single-threaded, events can run concurrently. The server will create a new process each time an event executes. Within the event’s code, a call to CONNECTION_ID() will return a unique value, as usual—even though there is no “connection” per se. (The return value of CONNECTION_ID() is really just the thread ID.) The process and thread will live only for the duration of the event’s execution. You can see it in SHOW PROCESSLIST by looking at the Command column, which will appear as “Connect”.

Although the process necessarily creates a thread to actually execute, the thread is destroyed at the end of event execution, not placed into the thread cache, and the Threads_created status counter is not incremented.

Preserving Comments in Stored Code

Stored procedures, stored functions, triggers, and events can all have significant amounts of code, and it’s useful to add comments. But the comments might not be stored inside the server, because the command-line client can strip them out. (This “feature” of the command-line client can be a nuisance, but c’est la vie.)

A useful trick for preserving comments in your stored code is to use version-specific comments, which the server sees as potentially executable code (i.e., code to be executed only if the server’s version number is that high or higher). The server and client programs know these aren’t ordinary comments, so they won’t discard them. To prevent the “code” from being executed, you can just use a very high version number, such as 99999. Let’s add some documentation to our trigger example to demystify what it does:

CREATE TRIGGER fake_statement_trigger

BEFORE INSERT ON sometable

FOR EACH ROW

BEGIN

DECLARE v_row_count INT DEFAULT ROW_COUNT();

/*!99999 ROW_COUNT() is 1 except for the first row, so this executes

only once per statement. */

IF v_row_count <> 1 THEN

-- Your code here

END IF;

END;

[97] The language is a subset of SQL/PSM, the Persistent Stored Modules part of the SQL standard. It is defined in ISO/IEC 9075-4:2003 (E).

[98] There are also some porting utilities, such as the tsql2mysql project (http://sourceforge.net/projects/tsql2mysql) for porting from Microsoft SQL Server.

Cursors

MySQL provides read-only, forward-only server-side cursors that you can use only from within a MySQL stored procedure or the low-level client API. MySQL’s cursors are read-only because they iterate over temporary tables rather than the tables where the data originated. They let you iterate over query results row by row and fetch each row into variables for further processing. A stored procedure can have multiple cursors open at once, and you can “nest” cursors in loops.

MySQL’s cursor design holds some snares for the unwary. Because they’re implemented with temporary tables, they can give developers a false sense of efficiency. The most important thing to know is that a cursor executes the entire query when you open it. Consider the following procedure:

1 CREATE PROCEDURE bad_cursor()

2 BEGIN

3 DECLARE film_id INT;

4 DECLARE f CURSOR FOR SELECT film_id FROM sakila.film;

5 OPEN f;

6 FETCH f INTO film_id;

7 CLOSE f;

8 END

This example shows that you can close a cursor before iterating through all of its results. A developer used to Oracle or Microsoft SQL Server might see nothing wrong with this procedure, but in MySQL it causes a lot of unnecessary work. Profiling this procedure with SHOW STATUS shows that it does 1,000 index reads and 1,000 inserts. That’s because there are 1,000 rows in sakila.film. All 1,000 reads and writes occur when line 5 executes, before line 6 executes.

The moral of the story is that if you close a cursor that fetches data from a large result set early, you won’t actually save work. If you need only a few rows, use LIMIT.

Cursors can cause MySQL to perform extra I/O operations too, and they can be very slow. Because in-memory temporary tables do not support the BLOB and TEXT types, MySQL has to create an on-disk temporary table for cursors over results that include these types. Even when that’s not the case, if the temporary table is larger than tmp_table_size, MySQL will create it on disk.

MySQL doesn’t support client-side cursors, but the client API has functions that emulate client-side cursors by fetching the entire result into memory. This is really no different from putting the result in an array in your application and manipulating it there. See Chapter 6 for more on the performance implications of fetching the entire result into client-side memory.

Prepared Statements

MySQL 4.1 and newer support server-side prepared statements that use an enhanced binary client/server protocol to send data efficiently between the client and server. You can access the prepared statement functionality through a programming library that supports the new protocol, such as the MySQL C API. The MySQL Connector/J and MySQL Connector/NET libraries provide the same capability to Java and .NET, respectively. There’s also a SQL interface to prepared statements, which we discuss later (it’s confusing).

When you create a prepared statement, the client library sends the server a prototype of the actual query you want to use. The server parses and processes this “skeleton” query, stores a structure representing the partially optimized query, and returns a statement handle to the client. The client library can execute the query repeatedly by specifying the statement handle.

Prepared statements can have parameters, which are question-mark placeholders for values that you can specify when you execute them. For example, you might prepare the following query:

INSERT INTO tbl(col1, col2, col3) VALUES (?, ?, ?);

You could then execute this query by sending the statement handle to the server, with values for each of the question-mark placeholders. You can repeat this as many times as desired. Exactly how you send the statement handle to the server will depend on your programming language. One way is to use the MySQL connectors for Java and .NET. Many client libraries that link to the MySQL C libraries also provide some interface to the binary protocol; you should read the documentation for your chosen MySQL API.

Using prepared statements can be more efficient than executing a query repeatedly, for several reasons:

§ The server has to parse the query only once.

§ The server has to perform some query optimization steps only once, as it caches a partial query execution plan.

§ Sending parameters via the binary protocol is more efficient than sending them as ASCII text. For example, a DATE value can be sent in just 3 bytes, instead of the 10 bytes required in ASCII. The biggest savings are for BLOB and TEXT values, which can be sent to the server in chunks rather than as a single huge piece of data. The binary protocol therefore helps save memory on the client, as well as reducing network traffic and the overhead of converting between the data’s native storage format and the non-binary protocol’s format.

§ Only the parameters—not the entire query text—need to be sent for each execution, which reduces network traffic.

§ MySQL stores the parameters directly into buffers on the server, which eliminates the need for the server to copy values around in memory.

Prepared statements can also help with security. There is no need to escape or quote values in the application, which is more convenient and reduces vulnerability to SQL injection or other attacks. (You should never trust user input, even when you’re using prepared statements.)

You can use the binary protocol only with prepared statements. Issuing queries through the normal mysql_query() API function will not use the binary protocol. Many client libraries let you “prepare” statements with question-mark placeholders and then specify the values for each execution, but these libraries are often only emulating the prepare-execute cycle in client-side code and are actually sending each query, as text with parameters replaced by values, to the server with mysql_query().

Prepared Statement Optimization

MySQL caches partial query execution plans for prepared statements, but some optimizations depend on the actual values that are bound to each parameter and therefore can’t be precomputed and cached. The optimizations can be separated into three types, based on when they must be performed. The following list applies at the time of this writing:

At preparation time

The server parses the query text, eliminates negations, and rewrites subqueries.

At first execution

The server simplifies nested joins and converts OUTER JOINs to INNER JOINs where possible.

At every execution

The server does the following:

§ Prunes partitions

§ Eliminates COUNT(), MIN(), and MAX() where possible

§ Removes constant subexpressions

§ Detects constant tables

§ Propagates equalities

§ Analyzes and optimizes ref, range, and index_merge access methods

§ Optimizes the join order

See Chapter 6 for more information on these optimizations. Even though some of them are theoretically possible to do only once, they are still performed as noted above.

The SQL Interface to Prepared Statements

A SQL interface to prepared statements is available in MySQL 4.1 and newer. It lets you instruct the server to create and execute prepared statements, but doesn’t use the binary protocol. Here’s an example of how to use a prepared statement through SQL:

mysql> SET @sql := 'SELECT actor_id, first_name, last_name

-> FROM sakila.actor WHERE first_name = ?';

mysql> PREPARE stmt_fetch_actor FROM @sql;

mysql> SET @actor_name := 'Penelope';

mysql> EXECUTE stmt_fetch_actor USING @actor_name;

+----------+------------+-----------+

| actor_id | first_name | last_name |

+----------+------------+-----------+

| 1 | PENELOPE | GUINESS |

| 54 | PENELOPE | PINKETT |

| 104 | PENELOPE | CRONYN |

| 120 | PENELOPE | MONROE |

+----------+------------+-----------+

mysql> DEALLOCATE PREPARE stmt_fetch_actor;

When the server receives these statements, it translates them into the same operations that would have been invoked by the client library. This means that you don’t have to use the special binary protocol to create and execute prepared statements.

As you can see, the syntax is a little awkward compared to just typing the SELECT statement directly. So what’s the advantage of using a prepared statement this way?

The main use case is for stored procedures. In MySQL 5.0, you can use prepared statements in stored procedures, and the syntax is similar to the SQL interface. This means you can build and execute “dynamic SQL” in stored procedures by concatenating strings, which makes stored procedures much more flexible. For example, here’s a sample stored procedure that can call OPTIMIZE TABLE on each table in a specified database:

DROP PROCEDURE IF EXISTS optimize_tables;

DELIMITER //

CREATE PROCEDURE optimize_tables(db_name VARCHAR(64))

BEGIN

DECLARE t VARCHAR(64);

DECLARE done INT DEFAULT 0;

DECLARE c CURSOR FOR

SELECT table_name FROM INFORMATION_SCHEMA.TABLES

WHERE TABLE_SCHEMA = db_name AND TABLE_TYPE = 'BASE TABLE';

DECLARE CONTINUE HANDLER FOR SQLSTATE '02000' SET done = 1;

OPEN c;

tables_loop: LOOP

FETCH c INTO t;

IF done THEN

LEAVE tables_loop;

END IF;

SET @stmt_text := CONCAT("OPTIMIZE TABLE ", db_name, ".", t);

PREPARE stmt FROM @stmt_text;

EXECUTE stmt;

DEALLOCATE PREPARE stmt;

END LOOP;

CLOSE c;

END//

DELIMITER ;

You can use this stored procedure as follows:

mysql> CALL optimize_tables('sakila');

Another way to write the loop in the procedure is as follows:

REPEAT

FETCH c INTO t;

IF NOT done THEN

SET @stmt_text := CONCAT("OPTIMIZE TABLE ", db_name, ".", t);

PREPARE stmt FROM @stmt_text;

EXECUTE stmt;

DEALLOCATE PREPARE stmt;

END IF;

UNTIL done END REPEAT;

There is an important difference between the two loop constructs: REPEAT checks the loop condition twice for each loop. This probably won’t cause a big performance problem in this example because we’re merely checking an integer’s value, but with more complex checks it could be costly.

Concatenating strings to refer to tables and databases is a good use for the SQL interface to prepared statements, because it lets you write statements that won’t work with parameters. You can’t parameterize database and table names because they are identifiers. Another scenario is dynamically setting a LIMIT clause, which you can’t specify with a parameter either.

The SQL interface is useful for testing a prepared statement by hand, but it’s otherwise not all that useful outside of stored procedures. Because the interface is through SQL, it doesn’t use the binary protocol, and it doesn’t really reduce network traffic because you have to issue extra queries to set the variables when there are parameters. You can benefit from using this interface in special cases, such as when preparing an enormous string of SQL that you’ll execute many times without parameters.

Limitations of Prepared Statements

Prepared statements have a few limitations and caveats:

§ Prepared statements are local to a connection, so another connection cannot use the same handle. For the same reason, a client that disconnects and reconnects loses the statements. (Connection pooling or persistent connections can alleviate this problem.)

§ Prepared statements cannot use the query cache in MySQL versions prior to 5.1.

§ It’s not always more efficient to use prepared statements. If you use a prepared statement only once, you might spend more time preparing it than you would just executing it as normal SQL. Preparing a statement also requires two extra round-trips to the server (to use prepared statements properly, you should deallocate them after use).

§ You cannot currently use a prepared statement inside a stored function (but you can use prepared statements inside stored procedures).

§ You can accidentally “leak” a prepared statement by forgetting to deallocate it. This can consume a lot of resources on the server. Also, because there is a single global limit on the number of prepared statements, a mistake such as this can interfere with other connections’ use of prepared statements.

§ Some operations, such as BEGIN, cannot be performed in prepared statements.

Probably the biggest limitation of prepared statements, however, is that it’s so easy to get confused about what they are and how they work. Sometimes it’s very hard to explain the difference between these three kinds of prepared statements:

Client-side emulated

The client driver accepts a string with placeholders, then substitutes the parameters into the SQL and sends the resulting query to the server.

Server-side

The driver sends a string with placeholders to the server with a special binary protocol, receives back a statement identifier, then executes the statement over the binary protocol by specifying the identifier and the parameters.

SQL interface

The client sends a string with placeholders to the server as a PREPARE SQL statement, sets SQL variables to parameter values, and finally executes the statement with an EXECUTE SQL statement. All of this happens via the normal textual protocol.

User-Defined Functions

MySQL has supported user-defined functions (UDFs) since ancient times. Unlike stored functions, which are written in SQL, you can write UDFs in any programming language that supports C calling conventions.

UDFs must be compiled and then dynamically linked with the server, making them platform-specific and giving you a lot of power. UDFs can be very fast and can access a large range of functionality in the operating system and available libraries. SQL stored functions are good for simple operations, such as calculating the great-circle distance between two points on the globe, but if you want to send network packets, you need a UDF. Also, while you can’t currently build aggregate functions in SQL stored functions, you can do this easily with a UDF.

With great power comes great responsibility. A mistake in your UDF can crash your whole server, corrupt the server’s memory and/or your data, and generally wreak all the havoc that any misbehaving C code can potentially cause.

NOTE