Games, Design and Play: A detailed approach to iterative game design (2016)

Part III: Practice

Chapter 9: Conceptualizing Your Game

Chapter 9: Conceptualizing Your Game

![]() Chapter 10: Prototyping Your Game

Chapter 10: Prototyping Your Game

![]() Chapter 11: Playtesting Your Game

Chapter 11: Playtesting Your Game

![]() Chapter 12: Evaluating Your Game

Chapter 12: Evaluating Your Game

![]() Chapter 13: Moving from Design to Production

Chapter 13: Moving from Design to Production

Chapter 9. Conceptualizing Your Game

This is the start of the journey to making a game. But what will that game be? There’s nothing more daunting than a blank screen, but there’s also no shortage of ideas, people, places, things, dreams, and other games to be inspired by. Conceptualizing your game starts with just a thought, but it doesn’t end there. Using techniques such as brainstorming, motivations, and design values will help turn those ideas into a game design.

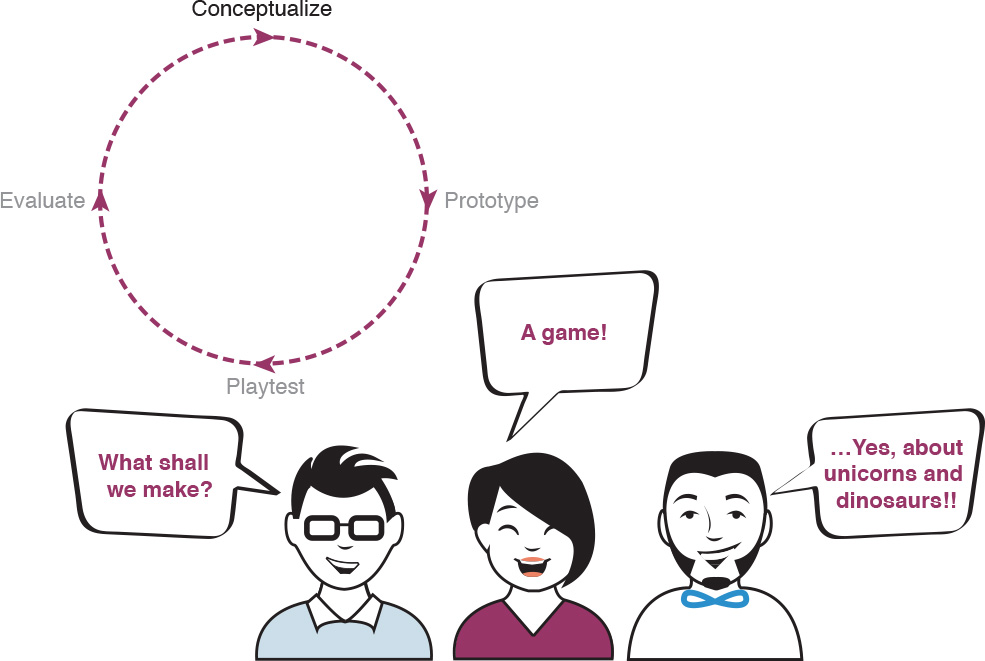

The first phase in the iterative game design process is conceptualize—developing an idea for the game and its play experience. At the beginning of the iterative design process, the focus is on generating the concept of the game. Once the first loop is complete, the conceptualize phase becomes more about refining and revising the game’s design and solving design problems that become visible through prototyping and playtesting. This chapter covers a set of processes and techniques for coming up with the initial concept for a game and covers methods like brainstorming, which will be helpful in deepening and refining the game as it moves through successive iterative loops.

Figure 9.1 Conceptualization begins the iterative cycle.

Generating Ideas for Your Game

There are many ways to come up with ideas for games. They can come from life experiences, media, books, and even other games. Chris Bell was inspired to create Way after getting lost in a Tokyo fish market and communicating with an elderly Japanese woman through gestures and movement to find his way out.1 Playing Way, you can see how this experience informed the game—it is all about nonverbal communication, using gestures to connect two players in a united goal. Way is a game that was inspired by an experience that meant something to Bell. But it simply provided the kernel of an idea for the game. The game itself is about nonverbal communication, but it doesn’t take place in a fish market in Tokyo. Ideas for games can come from many different places and be about anything you can imagine.

1 Chris Bell, “Designing for Friendship: Shaping Player Relationships with Rules and Freedom,” GDC 2012. www.gdcvault.com/play/1015706/Designing-for-Friendship-Shaping-Player.

While there are lots of videogames with fantastic worlds filled with space marines, wizards, and tiny plumbers, there’s much more we can make games about. In anna anthropy’s book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters, she talks about how all kinds of people are making games about all kinds of different topics. She lists some of the things games can be about, many of them based on personal experience:

What to Make a Game About? Your dog, your cat, your child, your boyfriend, your girlfriend, your mother, your father, your grandmother, your friends, your imaginary friends, the dream you had last night, the experience of opening the garage, a silent moment at a pond, a noisy moment in the heart of a city, the lifestyle of an imaginary creature, a trip on a boat, a trip on a plane, a trip down a vanishing path through a forest, waking up after twenty years of sleep, a sunset, a sunrise, a lingering smile, a heartfelt greeting, a bittersweet goodbye. Your past lives, your future lives, lies that you’ve told, lies you plan to tell, diary entries. Jumping over a pit, jumping into a pool, jumping into the sky and never coming down.

Anything. Everything.2

2 anna anthropy, Rise of the Videogame Zinesters: How Freaks, Normals, Amateurs, Artists, Dreamers, Drop-outs, Queers, Housewives, and People Like You Are Taking Back an Art Form. pp. 137-138, 2012.

As you can see from this list, games can be about stories from the personal to the fantastical and everything in-between. Ideas can certainly come from anywhere—and they can happen anytime. In fact, because they can come from all kinds of experiences, you might have an idea in the middle of the Tokyo fish market, on the beach, or in the shower.

Brainstorming

One of the best ways to generate and capture ideas is brainstorming. Brainstorming is a technique meant to fully explore all of the possible answers to a design question, coming up with as many ideas as possible. Techniques for brainstorming were first described by Alex F. Osborn in the 1953 book Applied Imagination.3 There, he outlined the primary rules for brainstorming:

3 Alex F. Osborn, Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Problem-solving, 1953.

![]() Quantity over quality: The golden rule of brainstorming is to come up with as many ideas as possible—no matter if you think they’re good, bad, or ugly.

Quantity over quality: The golden rule of brainstorming is to come up with as many ideas as possible—no matter if you think they’re good, bad, or ugly.

![]() Defer judgment: Don’t judge your ideas, or if you’re in a team, the ideas of others. The point of brainstorming is to come up with lots of ideas—not to limit them through judgment.

Defer judgment: Don’t judge your ideas, or if you’re in a team, the ideas of others. The point of brainstorming is to come up with lots of ideas—not to limit them through judgment.

![]() No buts (just ands): Add on to each others’ ideas (or your own). So instead of saying, “but there are no tubes to another dimension on a hike in the woods” say, “...and what if they lead to rooms full of coins and other goodies?”

No buts (just ands): Add on to each others’ ideas (or your own). So instead of saying, “but there are no tubes to another dimension on a hike in the woods” say, “...and what if they lead to rooms full of coins and other goodies?”

![]() Go wild: Let your ideas be as wild and improbable as possible. It’s easier to rein in a far-out idea than it is to try to breathe some fun and creativity into conservative ideas after the fact.

Go wild: Let your ideas be as wild and improbable as possible. It’s easier to rein in a far-out idea than it is to try to breathe some fun and creativity into conservative ideas after the fact.

![]() Get visual: Drawing something can sometimes capture an idea better than words.

Get visual: Drawing something can sometimes capture an idea better than words.

![]() Combine ideas: Once you have some ideas written down and drawn, mix them up, and look at how they combine. You could come up with something unique from the combination of different ideas.

Combine ideas: Once you have some ideas written down and drawn, mix them up, and look at how they combine. You could come up with something unique from the combination of different ideas.

There are many different ways to brainstorm, but the rules are always the same. It’s important not to limit ideas in the beginning. You want to build on each others’ ideas (by focusing on “yes, and...” and most importantly, to defer judgment. This can be challenging, as it’s natural to try to sort out the most promising direction—but don’t worry—that part is coming. The point of the brainstorm is to come up with lots of ideas to sort through later. Some brainstorming techniques work well with teams, while some are suited to individuals. Some are good for focusing on a single question, while other brainstorming methods help expand to many different possibilities. Some work well for the first pass at conceptualization, and others work best for later iterative cycles.

The goal of brainstorming isn’t just generating lots of ideas. It is to help get the creative juices flowing, to get team members thinking and riffing off one another and to value everyone’s ideas, no matter the role they might play in the design. It’s also a great way to come to agreement as a team about what’s important. It isn’t the only way to get ideas going, but it is one we use in our work and one we use with our students. Here are a few brainstorming techniques we have found particularly helpful during the conceptualization process.

Idea Speed-Dating

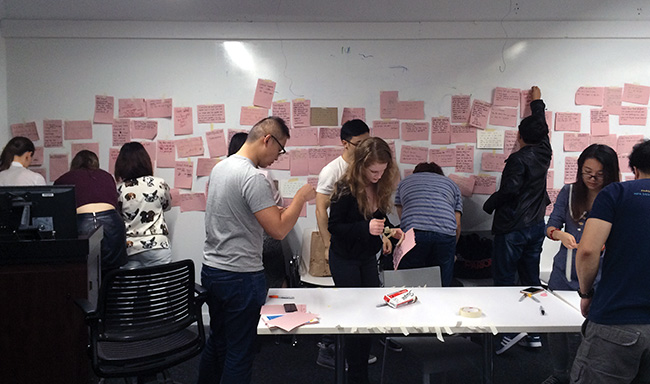

Idea speed-dating (see Figure 9.2) is a way for groups to generate a lot of ideas for games, often unexpected and exciting ideas. It’s best done at the very beginning of the game design process to come up with game concepts. It is also a productive way for teams to share all of their ideas and then collectively home in on the most promising ones.

Figure 9.2 A group participating in an idea speed-date.

To prepare, everyone should come with a game idea to share with the group. To get started, grab a timer, some 8.5″×11″ paper, markers, and pushpins or tape. Each participant should write a game idea on a sheet of paper in one or two sentences—maybe “Unicorns jousting with dinosaurs.” Once everyone has their ideas written down, the group should sit down in pairs to pitch their ideas to one another. For example, one person might present their unicorn and dinosaur idea, while the other might have something like “Soccer in complete darkness. The ball is the only source of light.” Then together the pair should spend a few minutes coming up with a game idea that is a mash-up of the two ideas. This might be “unicorns and dinosaurs trying to gain possession of a light-emitting soccer ball in the darkness so that they can find their way home.” (Remember “yes...and?”) This is a great way to build on the ideas of each other, coming up with new and unexpected concepts. Often, the newly mashed-up ideas are even more compelling than the original ones. The pair writes the idea on a sheet of paper, and those along with the original ideas are then looked at by the team and either voted on or chosen based on consensus.

We always suggest a form of distribution voting, where everyone has a set number of votes they can use as they like. Five is a good number, or you might modify this based on how many ideas have been generated and how many voters there are. Everyone adds votes to ideas by drawing a mark on the sheet for each of the votes they want to give that idea. It’s okay for a participant to assign all their votes to one idea if they think it is most promising, or distribute them on different ideas. Once the votes are made, we suggest discussing the most voted items and coming to consensus as a team (covered in Chapter 8, “Collaboration and Teamwork”), or using this as a way to build small teams out of a larger group through ideas. This is how we divide our game design classes into teams at the beginning of a semester.

“How Might We...” Questions

Another way to brainstorm ideas is around a “how might we...” question.4 This question is going to be the seed for the brainstorm. For example, “how might we model the fast food industry so that players learn about sustainability, obesity, and capitalism while still having fun?” Or, “how might we create a journey that generates a sense of awe and camaraderie?” The “how might we...” question opens up the brainstorm to all kinds of possibilities.

4 The “how might we...” question comes from an exercise that the design firm IDEO originated, found online as part of its design kit: www.designkit.org/methods/3.

In the previous example, we could ask, “how might we design a game around unicorns and dinosaurs trying to gain possession of a light-emitting soccer ball in the darkness so that they can find their way home?” This example is too specific for early-stage ideation but can work well later in the game design process. A good “how might we...” question is not too specific and not too broad (for example, “how might we create a competitive game?”). We want the question to generate a variety of possible concepts, so we could refine our question to enable that: “how might we create a game about creatures finding their way home?” As you can see, with the “how might we...” method we have a general concept or design problem already, and we’re using the brainstorm to consider the ways we can represent or solve it in a game. We’re thinking through the details of an idea to various ways the game might look, feel, and play.

In some cases, a “how might we...” question can leave more up in the air in terms of the gameplay and content. For example, “how might we create a game to help educate children about healthy eating habits?” Here we might brainstorm a game that is based around different kinds of gameplay, different themes, and stories, but all focused on the goal of educating young people about proper nutrition. Ultimately, the “how might we” method is a great way to use a question as the engine for your brainstorm, helping everyone focus on the same thing but come up with as many possible solutions as they can.

We like to use the silent method for “how might we” brainstorms (see Figure 9.3). To do this, make sure to have Post-it notes—the original square kind. They provide just the right amount of room to write down or draw one idea—not two or three ideas per note, just one. This is important so that these ideas can be sorted later and put into clusters. Markers are also essential. You can’t write too much with these, so it helps keep ideas to one idea on a Post-it. And the writing can be seen from far away—important when they are put up on the board to be discussed.

Figure 9.3 Brainstorming materials.

A silent brainstorm involves just that: silence. Set a timer for 10 minutes, make sure everyone has a stack of Post-it notes and a marker, and see who can come up with the most ideas. This is a great way to make sure that everyone’s ideas are captured, and the slightly competitive element drives everyone to go for the brainstorming rule “quantity over quality.” When the timer is done, everyone puts their ideas up on the wall and takes turns describing their ideas to the group. Ideas can be clustered into themes, new ideas developed from the combination of ideas, and ideas voted on, as in the idea speed-dating example. Finally, to make sure we don’t lose all these ideas, we always document in a couple of ways. We take pictures of the grouped Post-its and transcribe them to a shared document.

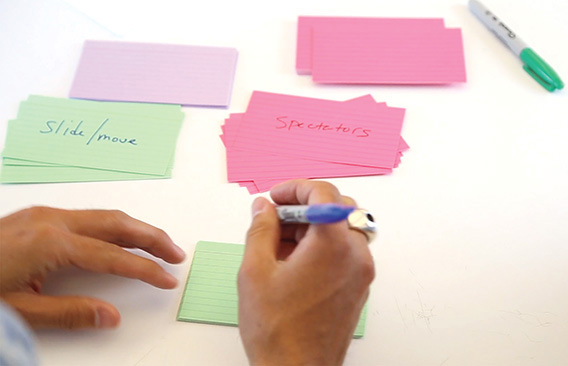

Noun-Verb-Adjective Brainstorming

A final way to brainstorm is to develop nouns, verbs, and adjectives to brainstorm around (see Figure 9.4). This form of brainstorming is a way to take a concept, break it apart, and make something new out of it. Or take a more complex concept and break it down into components that can form the basis for a game. What you end up with at the end of the exercise is a much better understanding of the potential objects (nouns), actions (verbs), and emotions (adjectives) in your game. We often use this kind of brainstorming to break down a real-world system and come up with ways to represent it in a game. For example, if we’re designing a game to help children make good eating choices, we can take a moment to write down on separate index cards as many nouns, verbs, and adjectives that come to mind. For nouns, we might have broccoli, snack, parents, teachers, friends, grocery store, farm, candy bar.... For verbs, eating, jumping, talking, playing, craving...and adjectives, salty, sweet, hilarious, fuzzy, gigantic, sleepy.... We can then shuffle the cards and form combinations to create a “how might we...” question for a brainstorm: “how might we create a game to promote healthy eating with gigantic jumping broccoli?” We often add a few unexpected verbs and adjectives in there to keep things interesting. You can also spend a few minutes brainstorming a variety of noun-verb-adjective combinations or have more than one of each. The key to a noun-verb-adjective brainstorm is to help you come up with unexpected solutions to a game design problem.

Figure 9.4 Cards from a noun, verb, and adjective exercise.

To get started, grab some index cards in three different colors along with some black markers. Using the silent brainstorming process discussed in the “how might we...” exercise, everyone should individually think up and write down one noun, verb, or adjective on a corresponding colored index card. Once the brainstorm is complete, review as a group to see which everyone likes and which don’t fit the collective vision for the game. More often than not, this discussion will generate more nouns, verbs, and adjectives—write those down, too.

Motivations

Once a game idea is formed, attention should shift to the game’s focus. Is it all about the play experience and the main actions players get to use? Or is it more about exploring a narrative world? Is it a game meant to convey a feeling or idea? Or a game meant to simulate something in the real world? Journalists use the term angle to describe the perspective from which they are telling a story and their intention in researching and writing the piece. Similarly, understanding the angle you will take to craft your game will help you identify important questions to answer. A motivation is just that—the angle you are taking in the game’s design. Motivations link the basic game design tools discussed in Chapter 2, “Basic Game Design Tools” with the kinds of play covered in Chapter 3, “The Kinds of Play” and help set the stage for your design values described in Chapter 6, “Design Values.”

The main motivations are designing around the main thing the player gets to do, designing around constraints, designing around a story, designing around personal experiences, abstracting the real world, and designing around the player. We tried to be fairly comprehensive in this set of motivations, but just as game ideas can come from anywhere, there are certainly game design motivations beyond these. The key here is to design based on the kind of play experiences we want to create, unconstrained by genre, technology, or other preconceived notions of games, while at the same time creating a clear direction for setting the game’s design values.

Designing Around the Main Thing the Player Gets to Do

Games allow us to do things we may not normally be able to do in real life, such as play a detective, an elven warrior, or an agile plumber. Or, for instance, they allow us the simple pleasures of surfing the sand dunes in Journey. It’s not a direct model; it’s an enhanced one that draws inspiration from the real-life event of running on the dunes and merges it with surfing and gliding to create a truly memorable experience. When designing around the main thing the player gets to do, the focus should be on the game’s actions. There are many ways to think about player experience, but here are some of the key questions:

![]() What does the player get to do? Games are all about doing. What actions does the player get to perform, both mentally and physically?

What does the player get to do? Games are all about doing. What actions does the player get to perform, both mentally and physically?

![]() What is going on in the game? What actions are happening inside the game to make players want to perform these actions?

What is going on in the game? What actions are happening inside the game to make players want to perform these actions?

![]() What are some adjectives that describe the play experience? What do you want players to feel while performing these actions?

What are some adjectives that describe the play experience? What do you want players to feel while performing these actions?

For Johann Sebastian Joust (or for short, J.S. Joust) (see Figure 9.5), the main thing the player gets to do is a big part of the entire experience of the game. Douglas Wilson, creator of the game, describes it as a “digitally augmented playground game.”5 In J.S. Joust, players hold Playstation Move Motion controllers, attempting to jostle other players’ controllers while remaining the last person standing. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos play in the background. When the music is slow, the Move controllers are more sensitive, forcing players to move very slowly, as if they are in slow motion. When the music speeds up, players can move more quickly, allowing them to try to jostle other players’ controllers with more speedy movements. The main action that inspired Douglas to design the game? Not necessarily jostling controllers, although that is one thing players do in the game to achieve the goal of being the last player standing. It’s actually moving in slow motion. This is the main action J.S. Joust is designed around—everything else being derived from that. As Douglas describes his approach: “my experience designing B.U.T.T.O.N. and J.S. Joust suggests a different starting point: find an activity that’s already fun—say, roughhousing your friends, or moving in slow motion—and only then work to iterate a game system into the mix.”6 Douglas describes seeing a playground game where players were moving in slow motion and realizing that there was something inherently fun about it for players and for those watching them. Building from that simple, theatrical action, J.S. Joust is just that—almost as much fun to watch as it is to play.

5 GDC China 2012, “The Unlikely Story of Johann Sebastian Joust,” Douglas Wilson.

6 “Designing for the Pleasures of Disputation—or—How to Make Friends by Trying to Kick Them!” Douglas Wilson, PhD dissertation, 2012.

Figure 9.5 Johann Sebastian Joust. Photo by Elliot Trinidad. Used with permission of the IndieCade International Festival of Independent Games.

Designing Around Constraints

In addition to the earlier question, “what can the player do?” is “what can the player not do?” Soccer, for example, constrains players’ ability to touch the ball, using anything but their hands. Or Terry Cavanaugh’s platformer vvvvvv (see Figure 9.6) doesn’t let the player jump at all. Instead, the player has to switch gravity to get over even the smallest step. This is really a different take on the “what the player gets to do” approach, as it is about creating play by making the player work around the obvious way to achieve a goal. Part of the fun of games is how they generate interesting challenges by forcing us to overcome limitations on our actions or resources.

Figure 9.6 Terry Cavanaugh’s vvvvvv.

In addition to constraining players, our game’s concept can benefit from constraint. Constraints are the designer’s best friend. In fact, the famed product designers Ray and Charles Eames say that, “design depends largely on constraints.”7 Constraints can be an inspiration behind your game’s design. In the early days of videogames, technology provided an incredibly influential constraint. Ever wonder why early Atari 2600 games used rectangular pixels over square ones? The answer is found in the relationship between the hardware and the television and how that information was processed. Designers those days used the limitations of the medium as inspiration in a variety of games, such as the horizontal rainbow colored bricks and paddles in Breakout (see Figure 9.7), which used the horizontal 8-bit graphics as a feature to define the shape of the bricks.

7 Qu’est ce que le design? (What Is Design?) at the Musáee des Arts Dáecoratifs, Palais de Louvre in 1972.

Figure 9.7 Breakout. Image credit: Fuyuan Cheng, used under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic.

Technological constraints are also found today, but in addition, constraints are often used to limit the possibilities of technologies that are far more developed. Canabalt, described earlier in this book, was a design in response to the challenge of creating a game that used only one button. The game’s designer, Adam Saltsman, describes his original idea, which was inspired by the concept of minimalism and developed at a game jam:

“As soon as I thought ‘Super Mario with one button,’ obstacles and level structures became obvious.”8

8 www.stuff.tv/features/weekend-read-how-canabalt-jumped-indie-game-jam-museum-modern-art#kUCG9h1o2d8YOqiT.99.

Constraint, both in terms of constraining what players can do and providing interesting limits on our game’s design, can generate creativity in overcoming them. Following are a few considerations we like to keep in mind when designing around constraints:

![]() What does the game keep the player from doing? How is the player’s ability to overcome challenges limited? What do these limitations open up for players?

What does the game keep the player from doing? How is the player’s ability to overcome challenges limited? What do these limitations open up for players?

![]() Where does the challenge come from? What is pushing back against the player’s ability to achieve their goals?

Where does the challenge come from? What is pushing back against the player’s ability to achieve their goals?

![]() How do players make decisions—real time or turn based? Limiting the player’s time and ability to evaluate their options and make their next action is a great form of constraint.

How do players make decisions—real time or turn based? Limiting the player’s time and ability to evaluate their options and make their next action is a great form of constraint.

![]() Is the game competitive, cooperative, or both? The goals and to what end players are interacting are forms of constraint.

Is the game competitive, cooperative, or both? The goals and to what end players are interacting are forms of constraint.

![]() What is the mix of strategy, skill, chance, and uncertainty? Are there unpredictable elements in the game? What interesting choices can the player make? How skilled must the player become to achieve the goals of the game?

What is the mix of strategy, skill, chance, and uncertainty? Are there unpredictable elements in the game? What interesting choices can the player make? How skilled must the player become to achieve the goals of the game?

![]() How does the player see, feel, and hear the game? What constraints come through the player’s ability to perceive the game? Is any information hidden?

How does the player see, feel, and hear the game? What constraints come through the player’s ability to perceive the game? Is any information hidden?

![]() How can we use constraint in our design process? What are some ways we can constrain our choices as designers? How can we use limitations to our advantage?

How can we use constraint in our design process? What are some ways we can constrain our choices as designers? How can we use limitations to our advantage?

Designing Around a Story

Another core consideration for a game might be telling an interesting story, or perhaps to be more precise in how games tell stories: developing a storyworld. Perhaps you are interested in developing a character through your game, or maybe you have an idea for a setting or historic moment to situate your game in. The Fullbright Company’s Gone Home is a great example of designing around a story. Instead of trying to tell a story through scenarios resolved by characters through actions, Gone Home asks players to uncover the story by exploring an empty house. Gone Home tells a story, but in a uniquely exploratory and game-like way. The player inhabits the role of Kaitlin, a college student coming home from college to discover the family house abandoned. The player then moves through the house examining objects, listening to tapes, reading letters, and otherwise learning about the family’s story through artifacts.

Questions to ask if you are interested in designing around a story include these:

![]() What is the game’s theme? What is the game about? Is there a point of view or moral to the story? In what kind of world does it take place? Is it inspired by a historic period?

What is the game’s theme? What is the game about? Is there a point of view or moral to the story? In what kind of world does it take place? Is it inspired by a historic period?

![]() What is the player’s role in telling the story? Is the player watching a story unfold, or are they an active participant? How do their actions advance the plot?

What is the player’s role in telling the story? Is the player watching a story unfold, or are they an active participant? How do their actions advance the plot?

![]() How many different outcomes or paths will there be through the story? Do players progress through a predetermined set of story elements? Does the story branch? Are there optional moments in the game?

How many different outcomes or paths will there be through the story? Do players progress through a predetermined set of story elements? Does the story branch? Are there optional moments in the game?

![]() What are some adjectives that describe how the story will make players feel? What emotional state will your story bring about in your players?

What are some adjectives that describe how the story will make players feel? What emotional state will your story bring about in your players?

![]() What are the important verbs in the story? What are the important nouns? Can the story be abstracted down to key actions, or verbs, and key people and things, or nouns? Can these in turn be used to develop the game’s structure?

What are the important verbs in the story? What are the important nouns? Can the story be abstracted down to key actions, or verbs, and key people and things, or nouns? Can these in turn be used to develop the game’s structure?

![]() What will the player be left thinking about after their play experience? Are the ideas you hope to explore in the game coming through the story? If so, what will it lead the player to think about?

What will the player be left thinking about after their play experience? Are the ideas you hope to explore in the game coming through the story? If so, what will it lead the player to think about?

Designing Around Personal Experiences

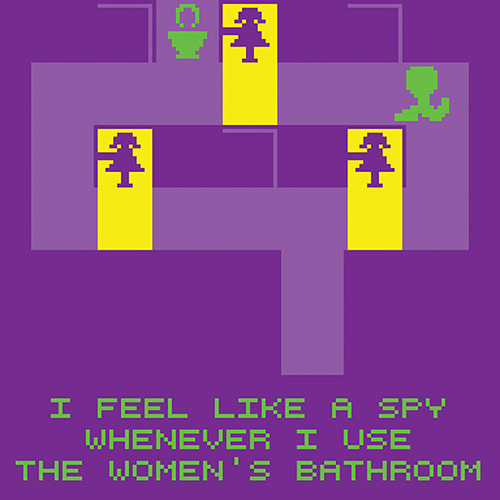

Personal experiences can be a big inspiration for creating games, although interestingly enough, the personal story is not as prevalent in games as it is in mediums like writing and film. This may be because we are early in videogames’ history and still developing a language and set of techniques to express ideas with games. That said, there are some pioneers out there making incredible games about personal experiences.

anna anthropy’s dys4ia (see Figure 9.8) is a journal game describing anna’s experiences with hormone replacement therapy. Players experience what anna experiences and thinks as they move through the different sections of the game. Way is an abstraction of Chris Bell’s personal experience—for instance, the game does not take place in the Tokyo fish market and does not include Bell as a protagonist, but it is still inspired by that one personal experience.

Figure 9.8 Screenshot from dys4ia.

Questions to ask if you are developing a game around personal experience include these:

![]() How autobiographical will the game be? Is this game a memoir of a particular experience you had? Will you include actual dialogue, places, and people? Images from your life?

How autobiographical will the game be? Is this game a memoir of a particular experience you had? Will you include actual dialogue, places, and people? Images from your life?

![]() Will the game be a more abstract representation of your experience? Is the game meant to express a feeling or experience you had but displace it from the particular details of your own? What kind of representations, settings, and characters would help express the experience?

Will the game be a more abstract representation of your experience? Is the game meant to express a feeling or experience you had but displace it from the particular details of your own? What kind of representations, settings, and characters would help express the experience?

![]() What are some of the verbs or actions you can include to help the player understand the experience and feel it for themself? What physical activities are involved in the experience? What actions can express the conflicts or challenges in the experience? How will the player unfold the experience through their interactions with it?

What are some of the verbs or actions you can include to help the player understand the experience and feel it for themself? What physical activities are involved in the experience? What actions can express the conflicts or challenges in the experience? How will the player unfold the experience through their interactions with it?

Abstracting the Real World

Games are a medium defined by systems. As Donella Meadows states, “A system is a set of things—people, cells, molecules, or whatever—interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time.”9Meadows’ definition is used to describe the systems that underlay much of how the world works. Games are systems too and are well suited to modeling systems that exist in the real world. They are also abstractions. The world itself is a pretty complicated place—games take that complexity and boil it down into simple rules. When abstracting a system in the real world, we need to choose a player point of view, a core set of actions, and a way to provide feedback to the player about the impact of their actions.

9 Donella H. Meadows, Thinking in Systems: A Primer, 2008.

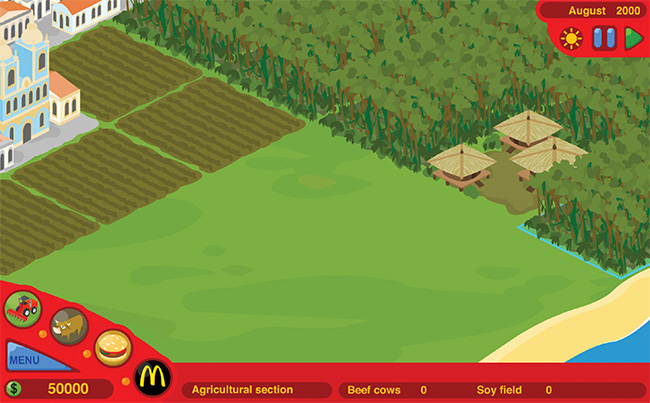

In Molleindustria’s McDonald’s Videogame (see Figure 9.9), Paolo Pedercini chose to show the system of fast food by leveling players up through different perspectives—from pasture to feedlot to restaurant to corporate board room. Each level has a different set of actions, constraints, and materials, but they all combine to contribute to the franchise’s bottom line: profit. The modeling makes it clear how difficult it is to run a profitable company without cutting corners or implementing questionable policies. The abstraction serves to tell a story and represents a set of concepts Pedercini wants to highlight.

Figure 9.9 Screenshot from McDonald’s Videogame.

Questions to ask when designing games that abstract the real world include these:

![]() How does the system in the real world work? What are the elements in the system? How are they connected? What are the dynamics of those connections? What are the inputs and outputs of the system?

How does the system in the real world work? What are the elements in the system? How are they connected? What are the dynamics of those connections? What are the inputs and outputs of the system?

![]() What does the game say about this system? How changeable is the system? What kinds of actions does the system reward? Is the system a reflection on a societal or a human problem?

What does the game say about this system? How changeable is the system? What kinds of actions does the system reward? Is the system a reflection on a societal or a human problem?

![]() How can player point of view and feedback help players understand how the system works? Is the player an element in the system, or are they above it, in a bird’s eye view? Do they have any control over how the system works, or are they subjected to the rules of the system? How does the game reward or penalize actions within the system?

How can player point of view and feedback help players understand how the system works? Is the player an element in the system, or are they above it, in a bird’s eye view? Do they have any control over how the system works, or are they subjected to the rules of the system? How does the game reward or penalize actions within the system?

![]() What does the abstraction leave out? Just as important is considering the things removed from the real-world phenomenon to create a simplified representation for the game.

What does the abstraction leave out? Just as important is considering the things removed from the real-world phenomenon to create a simplified representation for the game.

Designing Around the Player

For many games, players are among the most important considerations. Who do you imagine as the audience for your game? What are they like? A great tool for fleshing out your player is personas. Personas, a tool developed initially by Alan Cooper in his book The Inmates Are Running the Asylum,10 are fictional players that are based on the attributes we think our players will have. A persona has a name, age, job, education history, and other details, such as the kinds of games and other media they might like (or dislike, for that matter). Often, teams will create two or three personas to guide their design process. The first persona will be the primary one—the main player the team wants to design for. The second and third personas will be other players the team wants to keep in mind and who the team thinks will enjoy playing the game.

10 Alan Cooper, The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. New York: Sams-Pearson Education, 2004.

Whether you create personas or not, these questions are really helpful in understanding your players:

![]() Who is playing? This might be specific people, but it may also be a particular community or culture or most any other grouping of individuals.

Who is playing? This might be specific people, but it may also be a particular community or culture or most any other grouping of individuals.

![]() Where are they playing? Having a particular setting in mind is helpful, particularly if designing for installation, arcade, or other known space like a subway, a bus, at an event, and so on.

Where are they playing? Having a particular setting in mind is helpful, particularly if designing for installation, arcade, or other known space like a subway, a bus, at an event, and so on.

![]() When are they playing? Having a handle on a time period (such as daytime or evening) is helpful, but more important is what else players might be doing at that time—socializing, being alone at home, and so on.

When are they playing? Having a handle on a time period (such as daytime or evening) is helpful, but more important is what else players might be doing at that time—socializing, being alone at home, and so on.

![]() What else do they play? Having a sense of what kinds of games the ideal player engages with is helpful, too.

What else do they play? Having a sense of what kinds of games the ideal player engages with is helpful, too.

![]() What else do they like? Beyond games, what else does the player enjoy? Camping, cooking, or knitting? Films, comics, or music? Thinking about the other activities and mediums the player engages with will help think more broadly about the game.

What else do they like? Beyond games, what else does the player enjoy? Camping, cooking, or knitting? Films, comics, or music? Thinking about the other activities and mediums the player engages with will help think more broadly about the game.

All of these considerations around what the team wants to do with the game and the design motivations in making it take time to develop. Holding quick brainstorming sessions to work through these questions can be really helpful for generating ideas. Not only will it help focus everyone on each of these questions, it will provide a structure for discussions so that everyone’s ideas can be explored and captured.

Design Values Capture Motivations

Once the ideation process has generated motivations for the game, it is helpful to try to capture these in an organized manner. Our favorite method is design values, which we introduced in Chapter 6. Design values help give structure by converting your motivations into actionable principles. Using design values to guide the process while iterating through the creation of the game is essential to keeping up momentum, focus, and clarity as the game develops. In a collaboration, it also helps the team hold the same ideas in their heads as they work on their parts of the game. In addition to being guideposts, design values are like the scaffolding for the game. They guide the shape of the game and make sure it doesn’t grow in unexpected directions that take time and energy away from the core goals. It’s easy to get sidetracked when designing a game. The overall process can follow a long and winding path, and the last thing needed is to spend time working on an aspect of the game that complicates or dilutes the vision. Design values help the game keep shape and maintain a direction that is strong and clear. Recapping from Chapter 6:

![]() Experience: What does the player do when playing? As our friend, game designer, and educator Tracy Fullerton puts it, what does the player get to do? And how does this make them feel physically and emotionally?

Experience: What does the player do when playing? As our friend, game designer, and educator Tracy Fullerton puts it, what does the player get to do? And how does this make them feel physically and emotionally?

![]() Theme: What is the game about? How does it present this to players? What concepts, perspectives, or experiences might the player encounter during play? How are these delivered? Through story? Systems modeling? Metaphor?

Theme: What is the game about? How does it present this to players? What concepts, perspectives, or experiences might the player encounter during play? How are these delivered? Through story? Systems modeling? Metaphor?

![]() Point of view: What does the player see, hear, or feel? From what cultural reference point? How are the game and the information within it represented? Simple graphics? Stylized geometric shapes? Highly detailed models?

Point of view: What does the player see, hear, or feel? From what cultural reference point? How are the game and the information within it represented? Simple graphics? Stylized geometric shapes? Highly detailed models?

![]() Challenge: What kind of challenges does the game present? Mental challenge? Physical challenge? Or is it more a question of a challenging perspective, subject, or theme?

Challenge: What kind of challenges does the game present? Mental challenge? Physical challenge? Or is it more a question of a challenging perspective, subject, or theme?

![]() Decision-making: How and where do players make decisions? How are decisions presented?

Decision-making: How and where do players make decisions? How are decisions presented?

![]() Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: What skills does the game ask of the player? Is the development of strategy important to a fulfilling play experience? Does chance factor into the game? From what sources does uncertainty develop?

Skill, strategy, chance, and uncertainty: What skills does the game ask of the player? Is the development of strategy important to a fulfilling play experience? Does chance factor into the game? From what sources does uncertainty develop?

![]() Context: Who is the player? Where are they encountering the game? How did they find out about it? When are they playing it? Why are they playing it?

Context: Who is the player? Where are they encountering the game? How did they find out about it? When are they playing it? Why are they playing it?

![]() Emotions: What emotions might the game create in players?

Emotions: What emotions might the game create in players?

Remember, design values are guidelines—they’re not written in stone. Sometimes, as a game’s design evolves, ideas can arise and values may shift around them. Whether collaborating or working alone, it is important to revisit design values. If things drift (and they probably will) ask yourself why, and decide if you need to change the design values to accommodate something discovered in the design process. But be careful. Often, we have new ideas as we’re creating, and sometimes those ideas need to be set aside and worked on later, in a new game. Being able to distinguish whether you are drifting or moving forward is something that takes practice. A good rule of thumb is to ask how shifting a design value will strengthen the player experience of the game and what you want it to say.

Summary

The iterative game design process begins with an idea or maybe a lot of ideas. The trick is turning those ideas into raw materials from which a game can be created. The best way to begin this process is using brainstorm techniques, including these:

![]() Idea speed-dating: A process by which individuals quickly pitch a game idea to another person, who in turn pitches theirs. And from there, the pair generates a new idea that combines elements from both pitches. Once everyone in the group has pitched to everyone else, everyone votes on the strongest ideas.

Idea speed-dating: A process by which individuals quickly pitch a game idea to another person, who in turn pitches theirs. And from there, the pair generates a new idea that combines elements from both pitches. Once everyone in the group has pitched to everyone else, everyone votes on the strongest ideas.

![]() “How might we...” questions: A process by which a group explores questions to help them start designing their game. First, decide on a question. Silently brainstorm around this question by writing individual ideas on Post-it notes. After a set period of time, everyone puts their Post-its on the wall and explains them to one another.

“How might we...” questions: A process by which a group explores questions to help them start designing their game. First, decide on a question. Silently brainstorm around this question by writing individual ideas on Post-it notes. After a set period of time, everyone puts their Post-its on the wall and explains them to one another.

![]() Noun-verb-adjective brainstorm: A process for identifying the “moving parts” of a game concept. Using three colors of index cards, write down all the nouns, verbs, and adjectives you can think of relating to your game concept. After a set period of time, everyone shares their ideas with one another.

Noun-verb-adjective brainstorm: A process for identifying the “moving parts” of a game concept. Using three colors of index cards, write down all the nouns, verbs, and adjectives you can think of relating to your game concept. After a set period of time, everyone shares their ideas with one another.

At most any stage in the conceptualizing phase, it is helpful to think about the motivations for creating the game. There are six different considerations to take into account here:

![]() Designing around the main thing the player gets to do

Designing around the main thing the player gets to do

![]() Designing around constraints

Designing around constraints

![]() Designing around a story

Designing around a story

![]() Designing around personal experience

Designing around personal experience

![]() Abstracting the real world

Abstracting the real world

![]() Designing around the player

Designing around the player

It is helpful to convert the motivations for creating a game into a set of design values, a subject covered in detail in Chapter 6.