Developing Backbone.js Applications (2013)

Chapter 6. Backbone Extensions

Backbone is flexible, simple, and powerful. However, you may find that the complexity of the application you are working on requires more than what it provides out of the box. There are certain concerns that it just doesn’t address directly, as one of its goals is to be minimalist.

Take, for example, views, which provide a default render method that does nothing and produces no real results when called, despite most implementations using it to generate the HTML that the view manages. Also, models and collections have no built-in way of handling nested hierarchies—if you require this functionality, you need to write it yourself or use a plug-in.

In these cases, there are many existing Backbone plug-ins that can provide advanced solutions for large-scale Backbone apps. You can find a fairly complete list of the available plug-ins and frameworks on the Backbone wiki. With these add-ons, there is enough for applications of most sizes to be completed successfully.

In this section of the book, we will look at two popular Backbone add-ons: MarionetteJS and Thorax.

MarionetteJS (Backbone.Marionette)

By Derick Bailey and Addy Osmani

As we’ve seen, Backbone provides a great set of building blocks for our JavaScript applications. It gives us the core constructs that we need to build small to midsize apps, organize jQuery DOM events, or create single-page apps that support mobile devices and large-scale enterprise needs. But Backbone is not a complete framework. It’s a set of building blocks that leaves much of the application design, architecture, and scalability to the developer, including memory management, view management, and more.

MarionetteJS, also known as Backbone.Marionette, provides many of the features that the nontrivial application developer needs, above what Backbone itself provides. It is a composite application library that aims to simplify the construction of large-scale applications. It does this by providing a collection of common design and implementation patterns found in the applications that the creator, Derick Bailey, and many other contributors have been using to build Backbone apps.

Marionette’s key benefits include:

§ Allows you to scale applications out with modular, event-driven architecture

§ Provides sensible defaults, such as Underscore templates for view rendering

§ Can be easily modified to work with your application’s specific needs

§ Reduces boilerplate for views, with specialized view types

§ Builds on a modular architecture with an application and modules that attach to it

§ Allows you to compose your application’s visuals at runtime, with region and layout

§ Provides nested views and layouts within visual regions

§ Includes built-in memory management and zombie killing in views, regions, and layouts

§ Provides built-in event cleanup with the EventBinder

§ Incorporates event-driven architecture with the EventAggregator

§ Offers a flexible, as-needed architecture that allows you to pick and choose what you need

Marionette follows a similar philosophy to Backbone in that it provides a suite of components that can be used independently of one another, or used together to create significant advantages for developers. But it steps above the structural components of Backbone and provides an application layer, with more than a dozen components and building blocks.

Marionette’s components range greatly in the features they provide, but they all work together to create a composite application layer that can both reduce boilerplate code and provide a much-needed application structure. Its core components include various and specialized view types that take the boilerplate out of rendering common Backbone.Model and Backbone.Collection scenarios; an Application object and Module architecture to scale applications across subapplications, features, and files; integration of a command pattern, event aggregator, and request/response mechanism; and many more object types that can be extended in myriad ways to create an architecture that facilitates an application’s specific needs.

In spite of the large number of constructs that Marionette provides, though, you’re not required to use all of it just because you want to use some of it. As with Backbone itself, you can pick and choose which features you want to use and when. This allows you to work with other Backbone frameworks and plug-ins very easily. It also means that you are not required to engage in an all-or-nothing migration to begin using Marionette.

Boilerplate Rendering Code

Consider the code that it typically requires to render a view with Backbone and an Underscore template. We need a template to render, which can be placed in the DOM directly, and we need the JavaScript that defines a view that uses the template and populates it with data from a model.

<script type="text/html" id="my-view-template">

<div class="row">

<label>First Name:</label>

<span><%= firstName %></span>

</div>

<div class="row">

<label>Last Name:</label>

<span><%= lastName %></span>

</div>

<div class="row">

<label>Email:</label>

<span><%= email %></span>

</div>

</script>

var MyView = Backbone.View.extend({

template: $('#my-view-template').html(),

render: function(){

// compile the Underscore.js template

var compiledTemplate = _.template(this.template);

// render the template with the model data

var data = this.model.toJSON();

var html = compiledTemplate(data);

// populate the view with the rendered html

this.$el.html(html);

}

});

Once this is in place, you need to create an instance of your view and pass your model into it. Then you can take the view’s el and append it to the DOM in order to display the view.

var Derick = new Person({

firstName: 'Derick',

lastName: 'Bailey',

email: 'derickbailey@example.com'

});

var myView = new MyView({

model: Derick

})

myView.render();

$('#content').html(myView.el)

This is a standard setup for defining, building, rendering, and displaying a view with Backbone. This is also what we call boilerplate code—code that is repeated across every project and every implementation with the same functionality. It gets to be tedious and repetitious very quickly.

Enter Marionette’s ItemView—a simple way to reduce the boilerplate of defining a view.

Reducing Boilerplate with Marionette.ItemView

All of Marionette’s view types—with the exception of Marionette.View—include a built-in render method that handles the core rendering logic for you. We can take advantage of this by changing the MyView instance to inherit from one of these rather than Backbone.View. Instead of having to provide our own render method for the view, we can let Marionette render it for us. We’ll still use the same Underscore.js template and rendering mechanism, but its implementation is hidden behind the scenes. Thus, we can reduce the amount of code needed for this view.

var MyView = Marionette.ItemView.extend({

template: '#my-view-template'

});

And that’s it—that’s all you need to get the exact same behavior as the previous view implementation. Just replace Backbone.View.extend with Marionette.ItemView.extend, then get rid of the render method. You can still create the view instance with a model, call the rendermethod on the view instance, and display the view in the DOM the same way that we did before. But the view definition has been reduced to a single line of configuration for the template.

Memory Management

In addition to reducing code needed to define a view, Marionette includes some advanced memory management in all of its views, making the job of cleaning up a view instance and its event handlers easy.

Consider the following view implementation:

var ZombieView = Backbone.View.extend({

template: '#my-view-template',

initialize: function(){

// bind the model change to rerender this view

this.model.on('change', this.render, this);

},

render: function(){

// This alert is going to demonstrate a problem

alert('We`re rendering the view');

}

});

If we create two instances of this view using the same variable name for both instances, and then change a value in the model, how many times will we see the alert box?

var Person = Backbone.Model.extend({

defaults: {

"firstName": "Jeremy",

"lastName": "Ashkenas",

"email": "jeremy@example.com"

}

});

var Derick = new Person({

firstName: 'Derick',

lastName: 'Bailey',

email: 'derick@example.com'

});

// create the first view instance

var zombieView = new ZombieView({

model: Derick

});

// create a second view instance, reusing

// the same variable name to store it

zombieView = new ZombieView({

model: Derick

});

Derick.set('email', 'derickbailey@example.com');

Since we’re reusing the same zombieView variable for both instances, the first instance of the view will fall out of scope immediately after the second is created. This allows the JavaScript garbage collector to come along and clean it up, which should mean the first view instance is no longer active and no longer going to respond to the model’s change event.

But when we run this code, we end up with the alert box showing up twice!

The problem is caused by the model event binding in the view’s initialize method. Whenever we pass this.render as the callback method to the model’s on event binding, the model itself is being given a direct reference to the view instance. Since the model is now holding a reference to the view instance, replacing the zombieView variable with a new view instance is not going to let the original view fall out of scope. The model still has a reference; therefore, the view is still in scope.

Since the original view is still in scope, and the second view instance is also in scope, changing data on the model will cause both view instances to respond.

Fixing this is easy, though. You just need to call stopListening when the view is done with its work and ready to be closed. To do this, add a close method to the view.

var ZombieView = Backbone.View.extend({

template: '#my-view-template',

initialize: function(){

// bind the model change to rerender this view

this.listenTo(this.model, 'change', this.render);

},

close: function(){

// unbind the events that this view is listening to

this.stopListening();

},

render: function(){

// This alert is going to demonstrate a problem

alert('We`re rendering the view');

}

});

Then call close on the first instance when it is no longer needed, and only one view instance will remain alive. For more information about the listenTo and stopListening functions, see Chapter 3 and Derick’s post “Managing Events As Relationships, Not Just References”.

var Jeremy = new Person({

firstName: 'Jeremy',

lastName: 'Ashkenas',

email: 'jeremy@example.com'

});

// create the first view instance

var zombieView = new ZombieView({

model: Person

})

zombieView.close(); // double-tap the zombie

// create a second view instance, reusing

// the same variable name to store it

zombieView = new ZombieView({

model: Person

})

Person.set('email', 'jeremyashkenas@example.com');

Now we see only one alert box when this code runs.

Rather than having to manually remove these event handlers, though, we can let Marionette do it for us.

var ZombieView = Marionette.ItemView.extend({

template: '#my-view-template',

initialize: function(){

// bind the model change to rerender this view

this.listenTo(this.model, 'change', this.render);

},

render: function(){

// This alert is going to demonstrate a problem

alert('We`re rendering the view');

}

});

Notice in this case we are using a method called listenTo. This method comes from Backbone.Events, and is available in all objects that mix in Backbone.Events—including most Marionette objects. The listenTo method signature is similar to that of the on method, with the exception of passing the object that triggers the event as the first parameter.

Marionette’s views also provide a close event, in which the event bindings that are set up with the listenTo are automatically removed. This means we no longer need to define a close method directly, and when we use the listenTo method, we know that our events will be removed and our views will not turn into zombies.

But how do we automate the call to close on a view, in the real application? When and where do we call that? Enter the Marionette.Region—an object that manages the lifecycle of an individual view.

Region Management

After a view is created, it typically needs to be placed in the DOM so that it becomes visible. We usually do this with a jQuery selector and by setting the html() of the resulting object:

var Joe = new Person({

firstName: 'Joe',

lastName: 'Bob',

email: 'joebob@example.com'

});

var myView = new MyView({

model: Joe

})

myView.render();

// show the view in the DOM

$('#content').html(myView.el)

This, again, is boilerplate code. We shouldn’t have to manually call render and manually select the DOM elements to show the view. Furthermore, this code doesn’t lend itself to closing any previous view instance that might be attached to the DOM element we want to populate. And we’ve seen the danger of zombie views already.

To solve these problems, Marionette provides a Region object—an object that manages the lifecycle of individual views, displayed in a particular DOM element.

// create a region instance, telling it which DOM element to manage

var myRegion = new Marionette.Region({

el: '#content'

});

// show a view in the region

var view1 = new MyView({ /* ... */ });

myRegion.show(view1);

// somewhere else in the code,

// show a different view

var view2 = new MyView({ /* ... */ });

myRegion.show(view2);

There are several things to note here. First, we’re telling the region what DOM element to manage by specifying an el in the region instance. Second, we’re no longer calling the render method on our views. And lastly, we’re not calling close on our view, either, though this is getting called for us.

When we use a region to manage the lifecycle of our views, and display the views in the DOM, the region itself handles these concerns. When we pass a view instance into the show method of the region, the region will call the render method on the view for us. It will then take the resulting el of the view and populate the DOM element.

The next time we call the show method of the region, the region remembers that it is currently displaying a view. The region calls the close method on the view, removes it from the DOM, and then proceeds to run the render and display code for the new view that was passed in.

Since the region handles calling close for us, and we’re using the listenTo event binder in our view instance, we no longer have to worry about zombie views in our application.

Regions are not limited to just Marionette views, though. Any valid Backbone.View can be managed by a Marionette.Region. If your view happens to have a close method, it will be called when the view is closed. If not, the Backbone.View built-in method remove will be called instead.

Marionette Todo App

Having learned about Marionette’s high-level concepts, let’s now explore refactoring the Todo application we created in our first exercise to use it. You can find the complete code for this application in Derick’s TodoMVC fork.

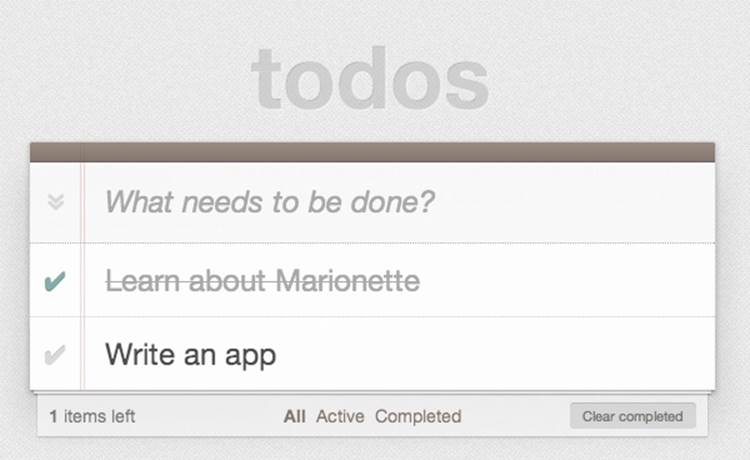

Our final implementation will be visually and functionally equivalent to the original app, as shown in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6-1. The Marionette Todo application we will be authoring

First, we define an application object representing our base TodoMVC app. This will contain initialization code and define the default layout regions for our app.

TodoMVC.js

var TodoMVC = new Marionette.Application();

TodoMVC.addRegions({

header : '#header',

main : '#main',

footer : '#footer'

});

TodoMVC.on('initialize:after', function(){

Backbone.history.start();

});

Regions are used to manage the content that’s displayed within specific elements, and the addRegions method on the TodoMVC object is just a shortcut for creating Region objects. We supply a jQuery selector for each region to manage (e.g., #header, #main, and #footer) and then tell the region to show various Backbone views within that region.

Once the application object has been initialized, we call Backbone.history.start() to route the initial URL.

Next, we define our layouts. A layout is a specialized type of view that directly extends Marionette.ItemView. This means it’s intended to render a single template and may or may not have a model (or item) associated with the template.

One of the main differences between a layout and an ItemView is that the layout contains regions. When defining a layout, we supply it with both a template and the regions that the template contains. After rendering the layout, we can display other views within the layout using the regions that were defined.

In our TodoMVC layout module, we define layouts for:

Header

Where we can create new todos

Footer

Where we summarize how many todos are remaining or have been completed

This captures some of the view logic that was previously in our AppView and TodoView.

Note that Marionette modules (such as the following) offer a simple module system that is used to create privacy and encapsulation in Marionette apps. These certainly don’t have to be used, however, and in Marionette and Flexibility, we’ll provide links to alternative implementations using RequireJS + AMD (asynchronous module definition) instead.

TodoMVC.Layout.js

TodoMVC.module('Layout', function(Layout, App, Backbone, Marionette, $, _){

// Layout Header View

// ------------------

Layout.Header = Marionette.ItemView.extend({

template : '#template-header',

// UI bindings create cached attributes that

// point to jQuery selected objects

ui : {

input : '#new-todo'

},

events : {

'keypress #new-todo': 'onInputKeypress'

},

onInputKeypress : function(evt) {

var ENTER_KEY = 13;

var todoText = this.ui.input.val().trim();

if ( evt.which === ENTER_KEY && todoText ) {

this.collection.create({

title : todoText

});

this.ui.input.val('');

}

}

});

// Layout Footer View

// ------------------

Layout.Footer = Marionette.Layout.extend({

template : '#template-footer',

// UI bindings create cached attributes that

// point to jQuery selected objects

ui : {

count : '#todo-count strong',

filters : '#filters a'

},

events : {

'click #clear-completed' : 'onClearClick'

},

initialize : function() {

this.listenTo(App.vent, 'todoList:filter', this.updateFilterSelection);

this.listenTo(this.collection, 'all', this.updateCount);

},

onRender : function() {

this.updateCount();

},

updateCount : function() {

var count = this.collection.getActive().length;

this.ui.count.html(count);

if (count === 0) {

this.$el.parent().hide();

} else {

this.$el.parent().show();

}

},

updateFilterSelection : function(filter) {

this.ui.filters

.removeClass('selected')

.filter('[href="#' + filter + '"]')

.addClass('selected');

},

onClearClick : function() {

var completed = this.collection.getCompleted();

completed.forEach(function destroy(todo) {

todo.destroy();

});

}

});

});

Next, we tackle application routing and workflow, such as controlling layouts in the page that can be shown or hidden.

Recall how Backbone routes trigger methods within the router, as shown here in our original workspace router from our first exercise:

var Workspace = Backbone.Router.extend({

routes:{

'*filter': 'setFilter'

},

setFilter: function( param ) {

// Set the current filter to be used

if (param){ param = param.trim()

}

app.TodoFilter = param ||";

// Trigger a collection filter event, causing hiding/unhiding

// of Todo view items

app.Todos.trigger('filter');

}

});

Marionette uses the concept of an AppRouter to simplify routing. This reduces the boilerplate for handling route events and allows routers to be configured to call methods on an object directly. We configure our AppRouter using appRoutes, which replaces the '*filter': 'setFilter' route defined in our original router and invokes a method on our controller.

The TodoList controller, also found in this next code block, handles some of the remaining visibility logic originally found in AppView and TodoView, albeit using very readable layouts.

TodoMVC.TodoList.js

TodoMVC.module('TodoList', function(TodoList, App, Backbone, Marionette, $, _){

// TodoList Router

// ---------------

//

// Handle routes to show the active versus complete todo items

TodoList.Router = Marionette.AppRouter.extend({

appRoutes : {

'*filter': 'filterItems'

}

});

// TodoList Controller (Mediator)

// ------------------------------

//

// Control the workflow and logic that exists at the application

// level, above the implementation detail of views and models

TodoList.Controller = function(){

this.todoList = new App.Todos.TodoList();

};

_.extend(TodoList.Controller.prototype, {

// Start the app by showing the appropriate views

// and fetching the list of todo items, if there are any

start: function(){

this.showHeader(this.todoList);

this.showFooter(this.todoList);

this.showTodoList(this.todoList);

this.todoList.fetch();

},

showHeader: function(todoList){

var header = new App.Layout.Header({

collection: todoList

});

App.header.show(header);

},

showFooter: function(todoList){

var footer = new App.Layout.Footer({

collection: todoList

});

App.footer.show(footer);

},

showTodoList: function(todoList){

App.main.show(new TodoList.Views.ListView({

collection : todoList

}));

},

// Set the filter to show complete or all items

filterItems: function(filter){

App.vent.trigger('todoList:filter', filter.trim() || '');

}

});

// TodoList Initializer

// --------------------

//

// Get the TodoList up and running by initializing the mediator

// when the application is started, pulling in all of the

// existing todo items and displaying them.

TodoList.addInitializer(function(){

var controller = new TodoList.Controller();

new TodoList.Router({

controller: controller

});

controller.start();

});

});

Controllers

In this particular app, note that controllers don’t add a great deal to the overall workflow. In general, Marionette’s philosophy on routers is that they should be an afterthought in the implementation of applications. Quite often, we’ve seen developers abuse Backbone’s routing system by making it the sole controller of the entire application workflow and logic.

This inevitably leads to mashing every possible combination of code into the router methods—view creation, model loading, coordinating different parts of the app, and so on. Developers such as Derick view this as a violation of the single-responsibility principle, or SRP, and separation of concerns.

Backbone’s router and history exist to deal with a specific aspect of browsers—managing the forward and back buttons. Marionette’s philosophy is that it should be limited to that, with the code that gets executed by the navigation being somewhere else. This allows the application to be used with or without a router. We can call a controller’s show method from a button click, from an application event handler, or from a router, and we will end up with the same application state no matter how we called that method.

Derick has written extensively about his thoughts on this topic, which you can read more about on his blog, Lostechies:

§ The Responsibilities Of The Various Pieces Of Backbone.js

§ Reducing Backbone Routers To Nothing More Than Configuration

§ 3 Stages Of A Backbone Application’s Startup

CompositeView

Our next task is defining the actual views for individual todo items and lists of items in our TodoMVC application. For this, we make use of Marionette’s CompositeViews. The idea behind a CompositeView is that it represents a visualization of a composite or hierarchical structure of leaves (or nodes) and branches.

Think of these views as being a hierarchy of parent-child models, and recursive by default. The same CompositeView type will be used to render each item in a collection that is handled by the composite view. For nonrecursive hierarchies, we are able to override the item view by defining an itemView attribute.

For our todo list item view, we define it as an ItemView; then, our todo list view is a CompositeView where we override the itemView setting and tell it to use the todo list item view for each item in the collection.

TodoMVC.TodoList.Views.js

TodoMVC.module('TodoList.Views', function

(Views, App, Backbone, Marionette, $, _){

// Todo List Item View

// -------------------

//

// Display an individual todo item, and respond to changes

// that are made to the item, including marking completed.

Views.ItemView = Marionette.ItemView.extend({

tagName : 'li',

template : '#template-todoItemView',

ui : {

edit : '.edit'

},

events : {

'click .destroy' : 'destroy',

'dblclick label' : 'onEditClick',

'keypress .edit' : 'onEditKeypress',

'click .toggle' : 'toggle'

},

initialize : function() {

this.listenTo(this.model, 'change', this.render);

},

onRender : function() {

this.$el.removeClass('active completed');

if (this.model.get('completed')) this.$el.addClass('completed');

else this.$el.addClass('active');

},

destroy : function() {

this.model.destroy();

},

toggle : function() {

this.model.toggle().save();

},

onEditClick : function() {

this.$el.addClass('editing');

this.ui.edit.focus();

},

onEditKeypress : function(evt) {

var ENTER_KEY = 13;

var todoText = this.ui.edit.val().trim();

if ( evt.which === ENTER_KEY && todoText ) {

this.model.set('title', todoText).save();

this.$el.removeClass('editing');

}

}

});

// Item List View

// --------------

//

// Controls the rendering of the list of items, including the

// filtering of active versus completed items for display.

Views.ListView = Marionette.CompositeView.extend({

template : '#template-todoListCompositeView',

itemView : Views.ItemView,

itemViewContainer : '#todo-list',

ui : {

toggle : '#toggle-all'

},

events : {

'click #toggle-all' : 'onToggleAllClick'

},

initialize : function() {

this.listenTo(this.collection, 'all', this.update);

},

onRender : function() {

this.update();

},

update : function() {

function reduceCompleted(left, right)

{ return left && right.get('completed'); }

var allCompleted = this.collection.reduce(reduceCompleted,true);

this.ui.toggle.prop('checked', allCompleted);

if (this.collection.length === 0) {

this.$el.parent().hide();

} else {

this.$el.parent().show();

}

},

onToggleAllClick : function(evt) {

var isChecked = evt.currentTarget.checked;

this.collection.each(function(todo){

todo.save({'completed': isChecked});

});

}

});

// Application Event Handlers

// --------------------------

//

// Handler for filtering the list of items by showing and

// hiding through the use of various CSS classes

App.vent.on('todoList:filter',function(filter) {

filter = filter || 'all';

$('#todoapp').attr('class', 'filter-' + filter);

});

});

At the end of the last code block, you will also notice an event handler using vent. This is an event aggregator that allows us to handle filterItem triggers from our TodoList controller.

Finally, we define the model and collection for representing our todo items. These are semantically not very different from the original versions we used in our first exercise and have been rewritten to better fit in with Derick’s preferred style of coding.

Todos.js

TodoMVC.module('Todos', function(Todos, App, Backbone, Marionette, $, _){

// Todo Model

// ----------

Todos.Todo = Backbone.Model.extend({

localStorage: new Backbone.LocalStorage('todos-backbone'),

defaults: {

title : '',

completed : false,

created : 0

},

initialize : function() {

if (this.isNew()) this.set('created', Date.now());

},

toggle : function() {

return this.set('completed', !this.isCompleted());

},

isCompleted: function() {

return this.get('completed');

}

});

// Todo Collection

// ---------------

Todos.TodoList = Backbone.Collection.extend({

model: Todos.Todo,

localStorage: new Backbone.LocalStorage('todos-backbone'),

getCompleted: function() {

return this.filter(this._isCompleted);

},

getActive: function() {

return this.reject(this._isCompleted);

},

comparator: function( todo ) {

return todo.get('created');

},

_isCompleted: function(todo){

return todo.isCompleted();

}

});

});

We finally kick everything off in our application index file by calling start on our main application object. Initialization is as follows:

$(function(){

// Start the TodoMVC app (defined in js/TodoMVC.js)

TodoMVC.start();

});

And that’s it!

Is the Marionette Implementation of the Todo App More Maintainable?

Derick feels that maintainability largely comes down to modularity, separating responsibilities (single responsibility principle and separation of concerns) by using patterns to keep concerns from being mixed together. It can, however, be difficult to simply extract things into separate modules for the sake of extraction, abstraction, or dividing the concept down into its simplest parts.

The SRP tells us quite the opposite—that we need to understand the context in which things change. What parts always change together, in this system? What parts can change independently? Without knowing this, we won’t know what pieces should be broken out into separate components and modules versus put together into the same module or object.

The way Derick organizes his apps into modules is by creating a breakdown of concepts at each level. A higher level module is a higher level of concern—an aggregation of responsibilities. Each responsibility is broken down into an expressive API set that is implemented by lower level modules (this is known as the dependency inversion principle). These are coordinated through a mediator, which he typically refers to as the controller in a module.

The way Derick organizes his files also plays directly into maintainability. He has written posts about the importance of keeping a sane application folder structure that I recommend reading:

§ JavaScript File & Folder Structures: Just Pick One

§ How to organize and structure the files and folders of HiloJS

Marionette and Flexibility

Marionette is a flexible framework, much like Backbone itself. It offers a wide variety of tools to help you create and organize an application architecture on top of Backbone, but like Backbone itself, it doesn’t dictate that you have to use all of its pieces in order to use any of them.

You’ll find the flexibility and versatility in Marionette easiest to understand by examining three variations of TodoMVC implemented with it that have been created for comparison purposes:

Simple, by Jarrod Overson

This version of TodoMVC shows some raw use of Marionette’s various view types, an application object, and the event aggregator. The objects that are created are added directly to the global namespace and are fairly straightforward. This is a great example of how you can use Marionette to augment existing code without having to rewrite everything around Marionette.

RequireJS, also by Jarrod

Using Marionette with RequireJS helps to create a modularized application architecture—a tremendously important concept in scaling JavaScript applications. RequireJS provides a powerful set of tools that can be leveraged to great advantage, making Marionette even more flexible than it already is.

Marionette modules, by Derick Bailey

RequireJS isn’t the only way to create a modularized application architecture. For those who wish to build applications in modules and namespaces, Marionette provides a built-in module and namespacing structure. This example application takes the simple version of the application and rewrites it into a namespaced application architecture, with an application controller (mediator/workflow object) that brings all of the pieces together.

Marionette certainly provides its share of opinions on how a Backbone application should be architected. The combination of modules, view types, event aggregator, application objects, and more can be used to create a very powerful and flexible architecture based on these opinions.

But as you can see, Marionette isn’t a completely rigid, “my way or the highway” framework. It provides many elements of an application foundation that you can mix and match with other architectural styles, such as AMD or namespacing, or you can use it to augment existing projects by reducing boilerplate code for rendering views.

This flexibility creates a much greater opportunity for Marionette to provide value to you and your projects, as it allows you to scale the use of Marionette with your application’s needs.

And So Much More

This is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg for Marionette, even for the ItemView and Region objects that we’ve explored. There is far more functionality, more features, and more flexibility and customizability that can be put to use in both of these objects. Then we have the other dozen or so components that Marionette provides, each with its own set of behaviors built in, customization and extension points, and more.

To learn more about Marionette’s components, the features they provide, and how to use them, check out the Marionette documentation, links to the wiki, links to the source code, the project core contributors, and much more at http://marionettejs.com.

Thorax

By Ryan Eastridge and Addy Osmani

Part of Backbone’s appeal is that it provides structure but is generally unopinionated, in particular when it comes to views. Thorax makes an opinionated decision to use Handlebars as its templating solution. Some of the patterns found in Marionette are found in Thorax as well. Marionette exposes most of these patterns as JavaScript APIs, whereas in Thorax they are often exposed as template helpers. This chapter assumes the reader has knowledge of Handlebars.

Ryan Eastridge and Kevin Decker developed Thorax to create Walmart’s mobile web application. This chapter is limited to Thorax’s templating features and patterns implemented in it that you can utilize in your application regardless of whether you choose to adopt Thorax. To learn more about other features implemented in Thorax and to download boilerplate projects, visit the Thorax website.

Hello World

In Backbone, when you create a new view, options passed are merged into any default options already present on a view and are exposed via this.options for later reference.

Thorax.View differs from Backbone.View in that there is no options object. All arguments passed to the constructor become properties of the view, which in turn become available to the template:

var view = new Thorax.View({

greeting: 'Hello',

template: Handlebars.compile('{{greeting}} World!')

});

view.appendTo('body');

In most examples in this chapter, a template property will be specified. In larger projects—including the boilerplate projects provided on the Thorax website—a name property would instead be used and a template of the same filename in your project would automatically be assigned to the view.

If a model is set on a view, its attributes also become available to the template:

var view = new Thorax.View({

model: new Thorax.Model({key: 'value'}),

template: Handlebars.compile('{{key}}')

});

Embedding Child Views

The view helper allows you to embed other views within a view. Child views can be specified as properties of the view:

var parent = new Thorax.View({

child: new Thorax.View(...),

template: Handlebars.compile('{{view child}}')

});

Or the name of a child view to initialize as well as any optional properties you wish to pass. In this case, the child view must have previously been created with extend and given a name property:

var ChildView = Thorax.View.extend({

name: 'child',

template: ...

});

var parent = new Thorax.View({

template: Handlebars.compile('{{view "child" key="value"}}')

});

The view helper may also be used as a block helper, in which case the block will be assigned as the template property of the child view:

{{#view child}}

child will have this block

set as its template property

{{/view}}

Handlebars is string-based, while Backbone.View instances have a DOM el. Since we are mixing metaphors, the embedding of views works via a placeholder mechanism where the view helper in this case adds the view passed to the helper to a hash of children, then injects placeholder HTML into the template, such as:

<div data-view-placeholder-cid="view2"></div>

Then, once the parent view is rendered, we walk the DOM in search of all the placeholders we created, replacing them with the child views’ els:

this.$el.find('[data-view-placeholder-cid]').forEach(function(el) {

var cid = el.getAttribute('data-view-placeholder-cid'),

view = this.children[cid];

view.render();

$(el).replaceWith(view.el);

}, this);

View Helpers

One of the most useful constructs in Thorax is Handlebars.registerViewHelper (not to be confused with Handlebars.registerHelper). This method will register a new block helper that will create and embed a HelperView instance with its template property set to the captured block. A HelperView instance is different from that of a regular child view in that its context will be that of the parent’s in the template. Like other child views, it will have a parent property set to that of the declaring view. Many of the built-in helpers in Thorax, including thecollection helper, are created in this manner.

A simple example would be an on helper that rerendered the generated HelperView instance each time an event was triggered on the declaring/parent view:

Handlebars.registerViewHelper('on', function(eventName, helperView) {

helperView.parent.on(eventName, function() {

helperView.render();

});

});

An example use of this would be to have a counter that would increment each time a button was clicked. This example makes use of Thorax’s button helper, which simply makes a button that calls a method when clicked:

{{#on "incremented"}}{{i}}{/on}}

{{#button trigger="incremented"}}Add{{/button}}

And the corresponding view class:

new Thorax.View({

events: {

incremented: function() {

++this.i;

}

},

initialize: function() {

this.i = 0;

},

template: ...

});

collection Helper

The collection helper creates and embeds a CollectionView instance, creating a view for each item in a collection, and updating when items are added, removed, or changed in the collection. The simplest usage of the helper would look like:

{{#collection kittens}}

<li>{{name}}</li>

{{/collection}}

And the corresponding view:

new Thorax.View({

kittens: new Thorax.Collection(...),

template: ...

});

The block in this case will be assigned as the template for each item view created, and the context will be the attributes of the given model. This helper accepts options that can be arbitrary HTML attributes, a tag option to specify the type of tag containing the collection, or any of the following:

item-template

A template to display for each model. If a block is specified, it will become the item-template.

item-view

A view class to use when each item view is created.

empty-template

A template to display when the collection is empty. If an inverse/else block is specified, it will become the empty-template.

empty-view

A view to display when the collection is empty.

Options and blocks can be used in combination, in this case creating a KittenView class with a template set to the captured block for each kitten in the collection:

{{#collection kittens item-view="KittenView" tag="ul"}}

<li>{{name}}</li>

{{else}}

<li>No kittens!</li>

{{/collection}}

Note that multiple collections can be used per view, and collections can be nested. This is useful when there are models that contain collections that contain models that contain:

{{#collection kittens}}

<h2>{{name}}</h2>

<p>Kills:</p>

{{#collection miceKilled tag="ul"}}

<li>{{name}}</li>

{{/collection}}

{{/collection}}

Custom HTML Data Attributes

Thorax makes heavy use of custom HTML data attributes to operate. While some make sense only within the context of Thorax, several are quite useful to have in any Backbone project for writing other functions against, or for general debugging. To add some to your views in non-Thorax projects, override the setElement method in your base view class:

MyApplication.View = Backbone.View.extend({

setElement: function() {

var response = Backbone.View.prototype.setElement.apply(this, arguments);

this.name && this.$el.attr('data-view-name', this.name);

this.$el.attr('data-view-cid', this.cid);

this.collection && this.$el.attr('data-collection-cid',

this.collection.cid);

this.model && this.$el.attr('data-model-cid', this.model.cid);

return response;

}

});

In addition to making your application more immediately comprehensible in the inspector, it’s now possible to extend jQuery/Zepto with functions to look up the closest view, model, or collection to a given element. To make it work, you have to save references to each view created in your base view class by overriding the _configure method:

MyApplication.View = Backbone.View.extend({

_configure: function() {

Backbone.View.prototype._configure.apply(this, arguments);

Thorax._viewsIndexedByCid[this.cid] = this;

},

dispose: function() {

Backbone.View.prototype.dispose.apply(this, arguments);

delete Thorax._viewsIndexedByCid[this.cid];

}

});

Then we can extend jQuery/Zepto:

$.fn.view = function() {

var el = $(this).closest('[data-view-cid]');

return el && Thorax._viewsIndexedByCid[el.attr('data-view-cid')];

};

$.fn.model = function(view) {

var $this = $(this),

modelElement = $this.closest('[data-model-cid]'),

modelCid = modelElement && modelElement.attr('[data-model-cid]');

if (modelCid) {

var view = $this.view();

return view && view.model;

}

return false;

};

Now instead of storing references to models randomly throughout your application to look up when a given DOM event occurs, you can use $(element).model(). In Thorax, this can be particularly useful in conjunction with the collection helper, which generates a view class (with amodel property) for each model in the collection. Here’s an example template:

{{#collection kittens tag="ul"}}

<li>{{name}}</li>

{{/collection}}

And the corresponding view class:

Thorax.View.extend({

events: {

'click li': function(event) {

var kitten = $(event.target).model();

console.log('Clicked on ' + kitten.get('name'));

}

},

kittens: new Thorax.Collection(...),

template: ...

});

A common antipattern in Backbone applications is to assign a className to a single view class. Consider using the data-view-name attribute as a CSS selector instead, saving CSS classes for things that will be used multiple times:

[data-view-name="child"] {

}

Thorax Resources

No Backbone-related tutorial would be complete without a Todo application. A Thorax implementation of TodoMVC is available, in addition to this far simpler example composed of this single Handlebars template:

{{#collection todos tag="ul"}}

<li{{#if done}} class="done"{{/if}}>

<input type="checkbox" name="done"{{#if done}} checked="checked"{{/if}}>

<span>{{item}}</span>

</li>

{{/collection}}

<form>

<input type="text">

<input type="submit" value="Add">

</form>

Here is the corresponding JavaScript:

var todosView = Thorax.View({

todos: new Thorax.Collection(),

events: {

'change input[type="checkbox"]': function(event) {

var target = $(event.target);

target.model().set({done: !!target.attr('checked')});

},

'submit form': function(event) {

event.preventDefault();

var input = this.$('input[type="text"]');

this.todos.add({item: input.val()});

input.val('');

}

},

template: '...'

});

todosView.appendTo('body');

To see Thorax in action on a large-scale website, visit walmart.com on any Android or iOS device. For a complete list of resources, visit the Thorax website.

Summary

While Backbone is a popular choice for building modern client-side applications, some projects require more decisions made right out of the box. Thorax provides a Rails-like development experience for working with Backbone, tackling many of these decisions for you. Thorax answers questions such as “What should a Backbone project look like?”, “What kind of directory structure should you use?”, and “How do you build your client-side app into deployable pieces for each platform you’re targeting?” While Thorax may not be for everyone, it offers some nice sugar for those looking to build more complex applications.