Java 8 Lambdas (2014)

Chapter 2. Lambda Expressions

The biggest language change in Java 8 is the introduction of lambda expressions—a compact way of passing around behavior. They are also a pretty fundamental building block that the rest of this book depends upon, so let’s get into what they’re all about.

Your First Lambda Expression

Swing is a platform-agnostic Java library for writing graphical user interfaces (GUIs). It has a fairly common idiom in which, in order to find out what your user did, you register an event listener. The event listener can then perform some action in response to the user input (see Example 2-1).

Example 2-1. Using an anonymous inner class to associate behavior with a button click

button.addActionListener(new ActionListener() {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event) {

System.out.println("button clicked");

}

});

In this example, we’re creating a new object that provides an implementation of the ActionListener class. This interface has a single method, actionPerformed, which is called by the button instance when a user actually clicks the on-screen button. The anonymous inner class provides the implementation of this method. In Example 2-1, all it does is print out a message to say that the button has been clicked.

NOTE

This is actually an example of using code as data—we’re giving the button an object that represents an action.

Anonymous inner classes were designed to make it easier for Java programmers to pass around code as data. Unfortunately, they don’t make it easy enough. There are still four lines of boilerplate code required in order to call the single line of important logic. Look how much gray we get if we color out the boilerplate:

button.addActionListener(new ActionListener() {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event) {

System.out.println("button clicked");

}

});

Boilerplate isn’t the only issue, though: this code is fairly hard to read because it obscures the programmer’s intent. We don’t want to pass in an object; what we really want to do is pass in some behavior. In Java 8, we would write this code example as a lambda expression, as shown inExample 2-2.

Example 2-2. Using a lambda expression to associate behavior with a button click

button.addActionListener(event -> System.out.println("button clicked"));

Instead of passing in an object that implements an interface, we’re passing in a block of code—a function without a name. event is the name of a parameter, the same parameter as in the anonymous inner class example. -> separates the parameter from the body of the lambda expression, which is just some code that is run when a user clicks our button.

Another difference between this example and the anonymous inner class is how we declare the variable event. Previously, we needed to explicitly provide its type—ActionEvent event. In this example, we haven’t provided the type at all, yet this example still compiles. What is happening under the hood is that javac is inferring the type of the variable event from its context—here, from the signature of addActionListener. What this means is that you don’t need to explicitly write out the type when it’s obvious. We’ll cover this inference in more detail soon, but first let’s take a look at the different ways we can write lambda expressions.

NOTE

Although lambda method parameters require less boilerplate code than was needed previously, they are still statically typed. For the sake of readability and familiarity, you have the option to include the type declarations, and sometimes the compiler just can’t work it out!

How to Spot a Lambda in a Haystack

There are a number of variations of the basic format for writing lambda expressions, which are listed in Example 2-3.

Example 2-3. Some different ways of writing lambda expressions

Runnable noArguments = () -> System.out.println("Hello World"); ![]()

ActionListener oneArgument = event -> System.out.println("button clicked"); ![]()

Runnable multiStatement = () -> { ![]()

System.out.print("Hello");

System.out.println(" World");

};

BinaryOperator<Long> add = (x, y) -> x + y; ![]()

BinaryOperator<Long> addExplicit = (Long x, Long y) -> x + y; ![]()

![]() shows how it’s possible to have a lambda expression with no arguments at all. You can use an empty pair of parentheses, (), to signify that there are no arguments. This is a lambda expression implementing Runnable, whose only method, run, takes no arguments and is a void return type.

shows how it’s possible to have a lambda expression with no arguments at all. You can use an empty pair of parentheses, (), to signify that there are no arguments. This is a lambda expression implementing Runnable, whose only method, run, takes no arguments and is a void return type.

![]() we have only one argument to the lambda expression, which lets us leave out the parentheses around the arguments. This is actually the same form that we used in Example 2-2.

we have only one argument to the lambda expression, which lets us leave out the parentheses around the arguments. This is actually the same form that we used in Example 2-2.

Instead of the body of the lambda expression being just an expression, in ![]() it’s a full block of code, bookended by curly braces ({}). These code blocks follow the usual rules that you would expect from a method. For example, you can return or throw exceptions to exit them. It’s also possible to use braces with a single-line lambda, for example to clarify where it begins and ends.

it’s a full block of code, bookended by curly braces ({}). These code blocks follow the usual rules that you would expect from a method. For example, you can return or throw exceptions to exit them. It’s also possible to use braces with a single-line lambda, for example to clarify where it begins and ends.

Lambda expressions can also be used to represent methods that take more than one argument, as in ![]() . At this juncture, it’s worth reflecting on how to read this lambda expression. This line of code doesn’t add up two numbers; it creates a function that adds together two numbers. The variable called add that’s a BinaryOperator<Long> isn’t the result of adding up two numbers; it is code that adds together two numbers.

. At this juncture, it’s worth reflecting on how to read this lambda expression. This line of code doesn’t add up two numbers; it creates a function that adds together two numbers. The variable called add that’s a BinaryOperator<Long> isn’t the result of adding up two numbers; it is code that adds together two numbers.

So far, all the types for lambda expression parameters have been inferred for us by the compiler. This is great, but it’s sometimes good to have the option of explicitly writing the type, and when you do that you need to surround the arguments to the lambda expression with parentheses. The parentheses are also necessary if you’ve got multiple arguments. This approach is demonstrated in ![]() .

.

NOTE

The target type of a lambda expression is the type of the context in which the lambda expression appears—for example, a local variable that it’s assigned to or a method parameter that it gets passed into.

What is implicit in all these examples is that a lambda expression’s type is context dependent. It gets inferred by the compiler. This target typing isn’t entirely new, either. As shown in Example 2-4, the types of array initializers in Java have always been inferred from their contexts. Another familiar example is null. You can know what the type of null is only once you actually assign it to something.

Example 2-4. The righthand side doesn’t specify its type; it is inferred from the context

final String[] array = { "hello", "world" };

Using Values

When you’ve used anonymous inner classes in the past, you’ve probably encountered a situation in which you wanted to use a variable from the surrounding method. In order to do so, you had to make the variable final, as demonstrated in Example 2-5. Making a variable final means that you can’t reassign to that variable. It also means that whenever you’re using a final variable, you know you’re using a specific value that has been assigned to the variable.

Example 2-5. A final local variable being captured by an anonymous inner class

final String name = getUserName();

button.addActionListener(new ActionListener() {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event) {

System.out.println("hi " + name);

}

});

This restriction is relaxed a bit in Java 8. It’s possible to refer to variables that aren’t final; however, they still have to be effectively final. Although you haven’t declared the variable(s) as final, you still cannot use them as nonfinal variable(s) if they are to be used in lambda expressions. If you do use them as nonfinal variables, then the compiler will show an error.

The implication of being effectively final is that you can assign to the variable only once. Another way to understand this distinction is that lambda expressions capture values, not variables. In Example 2-6, name is an effectively final variable.

Example 2-6. An effectively final variable being captured by an anonymous inner class

String name = getUserName();

button.addActionListener(event -> System.out.println("hi " + name));

I often find it easier to read code like this when the final is left out, because it can be just line noise. Of course, there are situations where it can be easier to understand code with an explicit final. Whether to use the effectively final feature comes down to personal choice.

If you assign to the variable multiple times and then try to use it in a lambda expression, you’ll get a compile error. For example, Example 2-7 will fail to compile with the error message: local variables referenced from a lambda expression must be final or effectively final.

Example 2-7. Fails to compile due to the use of a not effectively final variable

String name = getUserName();

name = formatUserName(name);

button.addActionListener(event -> System.out.println("hi " + name));

This behavior also helps explain one of the reasons some people refer to lambda expressions as “closures.” The variables that aren’t assigned to are closed over the surrounding state in order to bind them to a value. Among the chattering classes of the programming language world, there has been much debate over whether Java really has closures, because you can refer to only effectively final variables. To paraphrase Shakespeare: A closure by any other name will function all the same. In an effort to avoid such pointless debate, I’ll be referring to them as “lambda expressions” throughout this book. Regardless of what we call them, I’ve already mentioned that lambda expressions are statically typed, so let’s investigate the types of lambda expressions themselves: these types are called functional interfaces.

Functional Interfaces

NOTE

A functional interface is an interface with a single abstract method that is used as the type of a lambda expression.

In Java, all method parameters have types; if we were passing 3 as an argument to a method, the parameter would be an int. So what’s the type of a lambda expression?

There is a really old idiom of using an interface with a single method to represent a method and reusing it. It’s something we’re all familiar with from programming in Swing, and it is exactly what was going on in Example 2-2. There’s no need for new magic to be employed here. The exact same idiom is used for lambda expressions, and we call this kind of interface a functional interface. Example 2-8 shows the functional interface from the previous example.

Example 2-8. The ActionListener interface: from an ActionEvent to nothing

public interface ActionListener extends EventListener {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent event);

}

ActionListener has only one abstract method, actionPerformed, and we use it to represent an action that takes one argument and produces no result. Remember, because actionPerformed is defined in an interface, it doesn’t actually need the abstract keyword in order to be abstract. It also has a parent interface, EventListener, with no methods at all.

So it’s a functional interface. It doesn’t matter what the single method on the interface is called—it’ll get matched up to your lambda expression as long as it has a compatible method signature. Functional interfaces also let us give a useful name to the type of the parameter—something that can help us understand what it’s used for and aid readability.

The functional interface here takes one ActionEvent parameter and doesn’t return anything (void), but functional interfaces can come in many kinds. For example, they may take two parameters and return a value. They can also use generics; it just depends upon what you want to use them for.

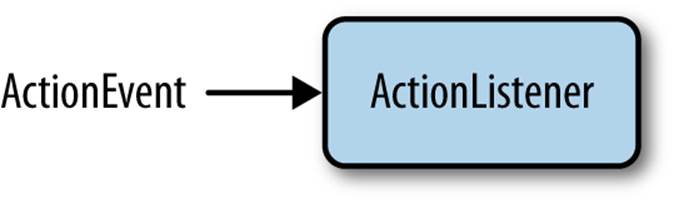

From now on, I’ll use diagrams to represent the different kinds of functional interfaces you’re encountering. The arrows going into the function represent arguments, and if there’s an arrow coming out, it represents the return type. For example, an ActionListener would look like Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1. The ActionListener interface showing an ActionEvent going in and nothing (void) coming out

Over time you’ll encounter many functional interfaces, but there is a core group in the Java Development Kit (JDK) that you will see time and time again. I’ve listed some of the most important functional interfaces in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1. Important functional interfaces in Java

|

Interface name |

Arguments |

Returns |

Example |

|

Predicate<T> |

T |

boolean |

Has this album been released yet? |

|

Consumer<T> |

T |

void |

Printing out a value |

|

Function<T,R> |

T |

R |

Get the name from an Artist object |

|

Supplier<T> |

None |

T |

A factory method |

|

UnaryOperator<T> |

T |

T |

Logical not (!) |

|

BinaryOperator<T> |

(T, T) |

T |

Multiplying two numbers (*) |

I’ve talked about what types functional interfaces take and mentioned that javac can automatically infer the types of parameters and that you can manually provide them, but when do you know whether to provide them? Let’s look a bit more at the details of type inference.

Type Inference

There are certain circumstances in which you need to manually provide type hints, and my advice is to do what you and your team find easiest to read. Sometimes leaving out the types removes line noise and makes it easier to see what is going on. Sometimes leaving them in can make it clearer what is going on. I’ve found that at first they can sometimes be helpful, but over time you’ll switch to adding them in only when they are actually needed. You can figure out whether they are needed from a few simple rules that I’ll introduce in this chapter.

The type inference used in lambdas is actually an extension of the target type inference introduced in Java 7. You might be familiar with Java 7 allowing you to use a diamond operator that asks javac to infer the generic arguments for you. You can see this in Example 2-9.

Example 2-9. Diamond inference for variables

Map<String, Integer> oldWordCounts = new HashMap<String, Integer>(); ![]()

Map<String, Integer> diamondWordCounts = new HashMap<>(); ![]()

For the variable oldWordCounts ![]() we have explicitly added the generic types, but diamondWordCounts

we have explicitly added the generic types, but diamondWordCounts ![]() uses the diamond operator. The generic types aren’t written out—the compiler just figures out what you want to do by itself. Magic!

uses the diamond operator. The generic types aren’t written out—the compiler just figures out what you want to do by itself. Magic!

It’s not really magic, of course. Here, the generic types to HashMap can be inferred from the type of diamondWordCounts ![]() . You still need to provide generic types on the variable that is being assigned to, though.

. You still need to provide generic types on the variable that is being assigned to, though.

If you’re passing the constructor straight into a method, it’s also possible to infer the generic types from that method. In Example 2-10, we pass a HashMap as an argument that already has the generic types on it.

Example 2-10. Diamond inference for methods

useHashmap(new HashMap<>());

...

private void useHashmap(Map<String, String> values);

In the same way that Java 7 allowed you to leave out the generic types for a constructor, Java 8 allows you to leave out the types for whole parameters of lambda expressions. Again, it’s not magic: javac looks for information close to your lambda expression and uses this information to figure out what the correct type should be. It’s still type checked and provides all the safety that you’re used to, but you don’t have to state the types explicitly. This is what we mean by type inference.

NOTE

It’s also worth noting that in Java 8 the type inference has been improved. The earlier example of passing new HashMap<>() into a useHashmap method actually wouldn’t have compiled in Java 7, even though the compiler had all the information it needed to figure things out.

Let’s go into a little more detail on this point with some examples.

In both of these cases we’re assigning the variables to a functional interface, so it’s easier to see what’s going on. The first example (Example 2-11) is a lambda that tells you whether an Integer is greater than 5. This is actually a Predicate—a functional interface that checks whether something is true or false.

Example 2-11. Type inference

Predicate<Integer> atLeast5 = x -> x > 5;

A Predicate is also a lambda expression that returns a value, unlike the previous ActionListener examples. In this case we’ve used an expression, x > 5, as the body of the lambda expression. When that happens, the return value of the lambda expression is the value its body evaluates to.

You can see from Example 2-12 that Predicate has a single generic type; here we’ve used an Integer. The only argument of the lambda expression implementing Predicate is therefore inferred as an Integer. javac can also check whether the return value is a boolean, as that is the return type of the Predicate method (see Figure 2-2).

Example 2-12. The predicate interface in code, generating a boolean from an Object

public interface Predicate<T> {

boolean test(T t);

}

Figure 2-2. The Predicate interface diagram, generating a boolean from an Object

Let’s look at another, slightly more complex functional interface example: the BinaryOperator interface, which is shown in Example 2-13. This interface takes two arguments and returns a value, all of which are the same type. In the code example we’ve used, this type is Long.

Example 2-13. A more complex type inference example

BinaryOperator<Long> addLongs = (x, y) -> x + y;

The inference is smart, but if it doesn’t have enough information, it won’t be able to make the right decision. In these cases, instead of making a wild guess it’ll just stop what it’s doing and ask for help in the form of a compile error. For example, if we remove some of the type information from the previous example, we get the code in Example 2-14.

Example 2-14. Code doesn’t compile due to missing generics

BinaryOperator add = (x, y) -> x + y;

This code results in the following error message:

Operator '+' cannot be applied to java.lang.Object, java.lang.Object.

That looks messy: what is going on here? Remember that BinaryOperator was a functional interface that had a generic argument. The argument is used as the type of both arguments, x and y, and also for its return type. In our code example, we didn’t give any generics to our add variable. It’s the very definition of a raw type. Consequently, our compiler thinks that its arguments and return values are all instances of java.lang.Object.

We will return to the topic of type inference and its interaction with method overloading in Overload Resolution, but there’s no need to understand more detail until then.

Key Points

§ A lambda expression is a method without a name that is used to pass around behavior as if it were data.

§ Lambda expressions look like this: BinaryOperator<Integer> add = (x, y) → x + y.

§ A functional interface is an interface with a single abstract method that is used as the type of a lambda expression.

Exercises

At the end of each chapter is a series of exercises to give you an opportunity to practice what you’ve learned during the chapter and help you learn the new concepts. The answers to these exercises can be found on GitHub.

1. Questions about the Function functional interface (Example 2-15).

Example 2-15. The function functional interface

public interface Function<T, R> {

R apply(T t);

}

a. Can you draw this functional interface diagrammatically?

b. What kind of lambda expressions might you use this functional interface for if you were writing a software calculator?

c. Which of these lambda expressions are valid Function<Long,Long> implementations?

d. x -> x + 1;

e. (x, y) -> x + 1;

x -> x == 1;

2. ThreadLocal lambda expressions. Java has a class called ThreadLocal that acts as a container for a value that’s local to your current thread. In Java 8 there is a new factory method for ThreadLocal that takes a lambda expression, letting you create a new ThreadLocal without the syntactic burden of subclassing.

a. Find the method in Javadoc or using your IDE.

b. The Java DateFormatter class isn’t thread-safe. Use the constructor to create a thread-safe DateFormatter instance that prints dates like this: “01-Jan-1970”.

3. Type inference rules. Here are a few examples of passing lambda expressions into functions. Can javac infer correct argument types for the lambda expressions? In other words, will they compile?

a. Runnable helloWorld = () -> System.out.println("hello world");

b. The lambda expression being used as an ActionListener:

c. JButton button = new JButton();

d. button.addActionListener(event ->

System.out.println(event.getActionCommand()));

e. Would check(x -> x > 5) be inferred, given the following overloads for check?

f. interface IntPred {

g. boolean test(Integer value);

h. }

i.

j. boolean check(Predicate<Integer> predicate);

k.

boolean check(IntPred predicate);

TIP

You might want to look up the method argument types in Javadoc or in your IDE in order to determine whether there are multiple valid overloads.