Web Development with Node and Express (2014)

Chapter 19. Integrating with Third-Party APIs

Increasingly, successful websites are not completely standalone. To engage existing users and find new users, integration with social networking is a must. To provide store locators or other location-aware services, using geolocation and mapping services is essential. It doesn’t stop there: more and more organizations are realizing that providing an API helps expand their service and makes it more useful.

In this chapter, we’ll be discussing the two most common integration needs: social media and geolocation.

Social Media

Social media is a great way to promote your product or service: if that’s your goal, the ability for your users to easily share your content on social media sites is essential. As I write this, the dominant social networking services are Facebook and Twitter. Google+ may be struggling for a piece of the pie, but don’t count them out: they are, after all, backed by one of the largest, most savvy Internet companies in the world. Sites like Pinterest, Instagram, and Flickr have their place, but they are usually a little more audience specific (for example, if your website is about DIY crafting, you would absolutely want to support Pinterest). Laugh if you will, but I predict that MySpace will make a comeback. Their site redesign is inspired, and it’s worth noting that they built it on Node.

Social Media Plugins and Site Performance

Most social media integration is a frontend affair. You reference the appropriate JavaScript files in your page, and it enables both incoming content (the top three stories from your Facebook page, for example) and outgoing content (the ability to tweet abut the page you’re on, for example). While this often represents the easiest path to social media integration, it comes at a cost: I’ve seen page load times double or even triple thanks to the additional HTTP requests. If page performance is important to you (and it should be, especially for mobile users), you should carefully consider how you integrate social media.

That said, the code that enables a Facebook “Like” button or a “Tweet” button leverages in-browser cookies to post on the user’s behalf. Moving this functionality to the backend would be difficult (and, in some instances, impossible). So if that is functionality you need, linking in the appropriate third-party library is your best option, even though it can affect your page performance. One saving grace is that the Facebook and Twitter APIs are so ubiquitous that there’s a high probability that your browser already has them cached, in which case there will be little effect on performance.

Searching for Tweets

Let’s say that we want to mention the top 10 most recent tweets that contain the hashtag #meadowlarktravel. We could use a frontend component to do this, but it will involve additional HTTP requests. Furthermore, if we do it on the backend, we have the option of caching the tweets for performance. Also, if we do the searching on the backend, we can “blacklist” uncharitable tweets, which would be more difficult on the frontend.

Twitter, like Facebook, allows you to create apps. It’s something of a misnomer: a Twitter app doesn’t do anything (in the traditional sense). It’s more like a set of credentials that you can use to create the actual app on your site. The easiest and most portable way to access the Twitter API is to create an app and use it to get access tokens.

Create a Twitter app by going to http://dev.twitter.com. Click your user icon in the upper-lefthand corner, and then select “My applications.” Click “Create a new application,” and follow the instructions. Once you have an application, you’ll see that you now have a consumer key and aconsumer secret. The consumer secret, as the name implies, should be kept secret: do not ever include this in responses sent to the client. If a third party were to get access to this secret, they could make requests on behalf of your application, which could have unfortunate consequences for you if the use is malicious.

Now that we have a consumer key and consumer secret, we can communicate with the Twitter REST API.

To keep our code tidy, we’ll put our Twitter code in a module called lib/twitter.js:

var https = require('https');

module.exports = function(twitterOptions){

return {

search: function(query, count, cb){

// TODO

}

};

};

This pattern should be starting to become familiar to you. Our module exports a function into which the caller passes a configuration object. What’s returned is an object containing methods. In this way, we can add functionality to our module. Currently, we’re only providing a searchmethod. Here’s how we will be using the library:

var twitter = require('./lib/twitter')({

consumerKey: credentials.twitter.consumerKey,

consumerSecret: credentials.twitter.consumerSecret,

});

twitter.search('#meadowlarktravel', 10, function(result){

// tweets will be in result.statuses

});

(Don’t forget to put a twitter property with consumerKey and consumerSecret in your credentials.js file.)

Before we implement the search method, we must provide some functionality to authenticate ourselves to Twitter. The process is simple: we use HTTPS to request an access token based on our consumer key and consumer secret. We only have to do this once: currently, Twitter does not expire access tokens (though you can invalidate them manually). Since we don’t want to request an access token every time, we’ll cache the access token so we can reuse it.

The way we’ve constructed our module allows us to create private functionality that’s not available to the caller. Specifically, the only thing that’s available to the caller is module.exports. Since we’re returning a function, only that function is available to the caller. Calling that function results in an object, and only the properties of that object are available to the caller. So we’re going to create a variable accessToken, which we’ll use to cache our access token, and a getAccessToken function that will get the access token. The first time it’s called, it will make a Twitter API request to get the access token. Subsequent calls will simply return the value of accessToken:

var https = require('https');

module.exports = function(twitterOptions){

// this variable will be invisible outside of this module

var accessToken;

// this function will be invisible outside of this module

function getAccessToken(cb){

if(accessToken) return cb(accessToken);

// TODO: get access token

}

return {

search: function(query, count, cb){

// TODO

},

};

};

Because getAccessToken may require an asynchronous call to the Twitter API, we have to provide a callback, which will be invoked when the value of accessToken is valid. Now that we’ve established the basic structure, let’s implement getAccessToken:

function getAccessToken(cb){

if(accessToken) return cb(accessToken);

var bearerToken = Buffer(

encodeURIComponent(twitterOptions.consumerKey) + ':' +

encodeURIComponent(twitterOptions.consumerSecret)

).toString('base64');

var options = {

hostname: 'api.twitter.com',

port: 443,

method: 'POST',

path: '/oauth2/token?grant_type=client_credentials',

headers: {

'Authorization': 'Basic ' + bearerToken,

},

};

https.request(options, function(res){

var data = '';

res.on('data', function(chunk){

data += chunk;

});

res.on('end', function(){

var auth = JSON.parse(data);

if(auth.token_type!=='bearer') {

console.log('Twitter auth failed.');

return;

}

accessToken = auth.access_token;

cb(accessToken);

});

}).end();

}

The details of constructing this call are available on Twitter’s developer documentation page for application-only authentication. Basically, we have to construct a bearer token that’s a base64-encoded combination of the consumer key and consumer secret. Once we’ve constructed that token, we can call the /oauth2/token API with the Authorization header containing the bearer token to request an access token. Note that we must use HTTPS: if you attempt to make this call over HTTP, you are transmitting your secret key unencrypted, and the API will simply hang up on you.

Once we receive the full response from the API (we listen for the end event of the response stream), we can parse the JSON, make sure the token type is bearer, and be on our merry way. We cache the access token, then invoke the callback.

Now that we have a mechanism for obtaining an access token, we can make API calls. So let’s implement our search method:

search: function(query, count, cb){

getAccessToken(function(accessToken){

var options = {

hostname: 'api.twitter.com',

port: 443,

method: 'GET',

path: '/1.1/search/tweets.json?q=' +

encodeURIComponent(query) +

'&count=' + (count || 10),

headers: {

'Authorization': 'Bearer ' + accessToken,

},

};

https.request(options, function(res){

var data = '';

res.on('data', function(chunk){

data += chunk;

});

res.on('end', function(){

cb(JSON.parse(data));

});

}).end();

});

},

Rendering Tweets

Now we have the ability to search tweets…so how do we display them on our site? Largely, it’s up to you, but there are some things to consider. Twitter has an interest in making sure its data is used in a manner consistent with the brand. To that end, it does have display requirements, which employ functional elements you must include to display a tweet.

There is some wiggle room in the requirements (for example, if you’re displaying on a device that doesn’t support images, you don’t have to include the avatar image), but for the most part, you’ll end up with something that looks very much like an embedded tweet. It’s a lot of work, and there is a way around it…but it involves linking to Twitter’s widget library, which is the very HTTP request we’re trying to avoid.

If you need to display tweets, your best bet is to use the Twitter widget library, even though it incurs an extra HTTP request (again, because of Twitter’s ubiquity, that resource is probably already cached by the browser, so the performance hit may be negligible). For more complicated use of the API, you’ll still have to access the REST API from the backend, so you will probably end up using the REST API in concert with frontend scripts.

Let’s continue with our example: we want to display the top 10 tweets that mention the hashtag #meadowlarktravel. We’ll use the REST API to search for the tweets and the Twitter widget library to display them. Since we don’t want to run up against usage limits (or slow down our server), we’ll cache the tweets and the HTML to display them for 15 minutes.

We’ll start by modifying our Twitter library to include a method embed, which gets the HTML to display a tweet (make sure you have var querystring = require('querystring'); at the top of the file):

embed: function(statusId, options, cb){

if(typeof options==='function') {

cb = options;

options = {};

}

options.id = statusId;

getAccessToken(function(accessToken){

var requestOptions = {

hostname: 'api.twitter.com',

port: 443,

method: 'GET',

path: '/1.1/statuses/oembed.json?' +

querystring.stringify(options);

headers: {

'Authorization': 'Bearer ' + accessToken,

},

};

https.request(requestOptions, function(res){

var data = '';

res.on('data', function(chunk){

data += chunk;

});

res.on('end', function(){

cb(JSON.parse(data));

});

}).end();

});

},

Now we’re ready to search for, and cache, tweets. In our main app file, let’s create an object to store the cache:

var topTweets = {

count: 10,

lastRefreshed: 0,

refreshInterval: 15 * 60 * 1000,

tweets: [],

}

Next we’ll create a function to get the top tweets. If they’re already cached, and the cache hasn’t expired, we simply return topTweets.tweets. Otherwise, we perform a search and then make repeated calls to embed to get the embeddable HTML. Because of this last bit, we’re going to introduce a new concept: promises. A promise is a technique for managing asynchronous functionality. An asynchronous function will return immediately, but we can create a promise that will resolve once the asynchronous part has been completed. We’ll use the Q promises library, so make sure you run npm install --save q and put var Q = require(q); at the top of your app file. Here’s the function:

function getTopTweets(cb){

if(Date.now() < topTweets.lastRefreshed + topTweets.refreshInterval)

return cb(topTweets.tweets);

twitter.search('#meadowlarktravel', topTweets.count, function(result){

var formattedTweets = [];

var promises = [];

var embedOpts = { omit_script: 1 };

result.statuses.forEach(function(status){

var deferred = Q.defer();

twitter.embed(status.id_str, embedOpts, function(embed){

formattedTweets.push(embed.html);

deferred.resolve();

});

promises.push(deferred.promise);

});

Q.all(promises).then(function(){

topTweets.lastRefreshed = Date.now();

cb(topTweets.tweets = formattedTweets);

});

});

}

If you’re new to asynchronous programming, this may seem very alien to you, so let’s take a moment and analyze what’s happening here. We’ll examine a simplified example, where we do something to each element of a collection asynchronously.

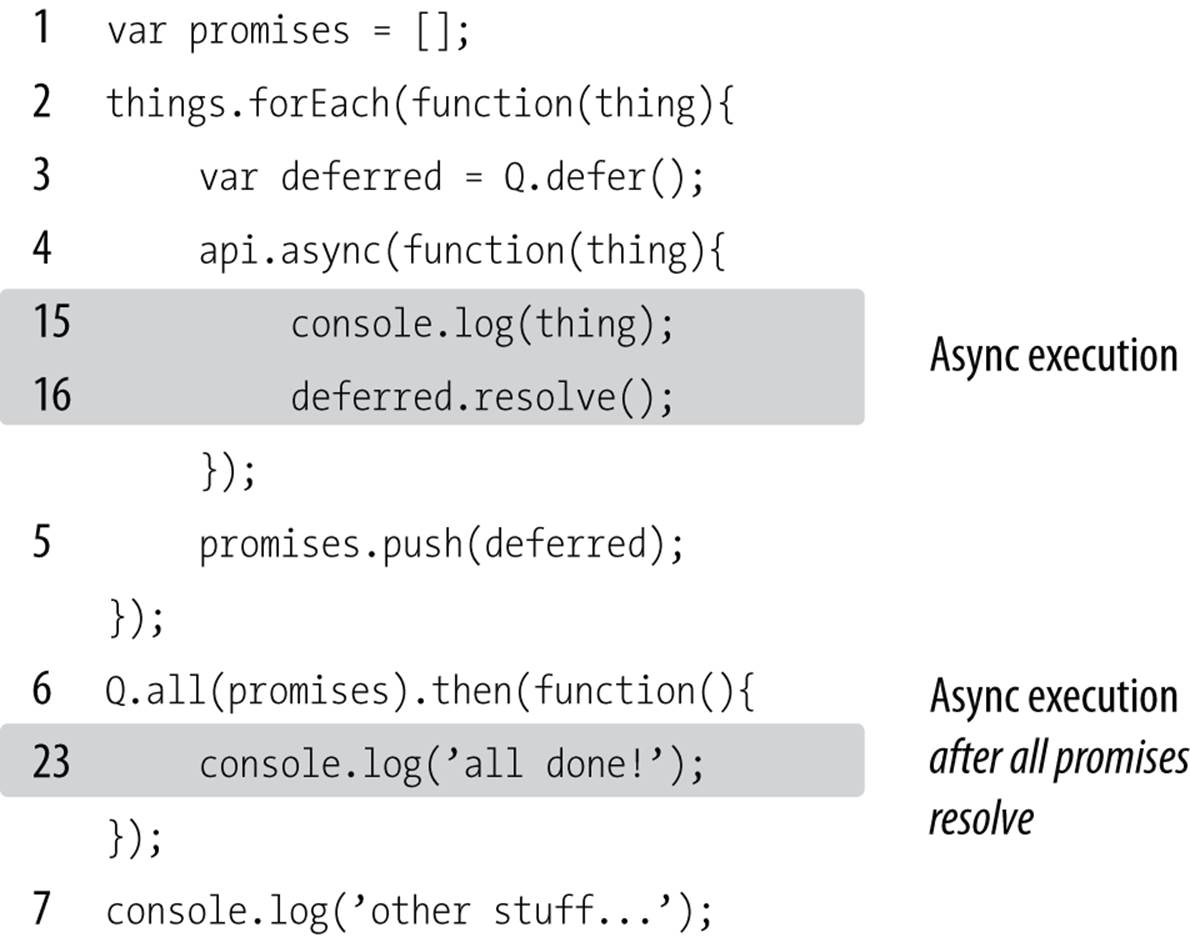

In Figure 19-1, I’ve assigned arbitrary execution steps. They’re arbitrary in that the first async block could be step 23 or 50 or 500, depending on how many other things are going on in your application; likewise, the second async block could happen at any time (but, thanks to promises, we know it has to happen after the first block).

Figure 19-1. Promises

In step 1, we create an array to store our promises, and in step 2, we start iterating over our collection of things. Note that even though forEach takes a function, it is not asynchronous: the function will be called synchronously for each item in the collection, which is why we know that step 3 is inside the function. In step 4, we call api.async, which represents a method that works asynchronously. When it’s done, it will invoke the callback you pass in. Note that console.log(num) will not be step 4: that’s because asynchronous function hasn’t had a chance to finish and invoke the callback. Instead, line 5 executes (simply adding the promise we’ve created to the array), and then starts again (step 6 will be the same line as step 3). Once the iteration has completed (three times), the forEach loop is over, and line 12 executes. Line 12 is special: it says, “when all the promises have resolved, then execute this function.” In essence, this is another asynchronous function, but this one won’t execute until all three of our calls to api.async complete. Line 13 executes, and something is printed to the console. So even though console.log(num)appears before console.log('other stuff…') in the code, “other stuff” will be printed first. After line 13, “other stuff” happens. At some point, there will be nothing left to do, and the JavaScript engine will start looking for other things to do. So it proceeds to execute our first asynchronous function: when that’s done, the callback is invoked, and we’re at steps 23 and 24. Those two lines will be repeated two more times. Once all the promises have been resolved, then (and only then) can we get to step 35.

Asynchronous programming (and promises) can take a while to wrap your head around, but the payoff is worth it: you’ll find yourself thinking in entirely new, more productive ways.

Geocoding

Geocoding refers to the process of taking a street address or place name (Bletchley Park, Sherwood Drive, Bletchley, Milton Keynes MK3 6EB, UK) and converting it to geographic coordinates (latitude 51.9976597, longitude –0.7406863). If your application is going to be doing any kind of geographic calculation—distances or directions—or displaying a map, then you’ll need geographic coordinates.

NOTE

You may be used to seeing geographic coordinates specified in degrees, minutes, and seconds (DMS). Geocoding APIs and mapping services use a single floating-point number for latitude and longitude. If you need to display DMS coordinates, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/geographic_coordinate_conversion.

Geocoding with Google

Both Google and Bing offer excellent REST services for Geocoding. We’ll be using Google for our example, but the Bing service is very similar. First, let’s create a module lib/geocode.js:

var http = require('http');

module.exports = function(query, cb){

var options = {

hostname: 'maps.googleapis.com',

path: '/maps/api/geocode/json?address=' +

encodeURIComponent(query) + '&sensor=false',

};

http.request(options, function(res){

var data = '';

res.on('data', function(chunk){

data += chunk;

});

res.on('end', function(){

data = JSON.parse(data);

if(data.results.length){

cb(null, data.results[0].geometry.location);

} else {

cb("No results found.", null);

}

});

}).end();

}

Now we have a function that will contact the Google API to geocode an address. If it can’t find an address (or fails for any other reason), an error will be returned. The API can return multiple addresses. For example, if you search for “10 Main Street” without specifying a city, state, or postal code, it will return dozens of results. Our implementation simply picks the first one. The API returns a lot of information, but all we’re currently interested in are the coordinates. You could easily modify this interface to return more information. See the Google geocoding API documentationfor more information about the data the API returns. Note that we included &sensor=false in the API request: this is a required field that should be set to true for devices that have a location sensor, such as mobile phones. Your server is probably not location aware, so it should be set tofalse.

Usage restrictions

Both Google and Bing have usage limits for their geocoding API to prevent abuse, but they’re very high. At the time of writing, Google’s limit is 2,500 requests per 24-hour period. Google’s API also requires that you use Google Maps on your website. That is, if you’re using Google’s service to geocode your data, you can’t turn around and display that information on a Bing map without violating the terms of service. Generally, this is not an onerous restriction, as you probably wouldn’t be doing geocoding unless you intended to display locations on a map. However, if you like Bing’s maps better than Google’s, or vice versa, you should be mindful of the terms of service and use the appropriate API.

Geocoding Your Data

Let’s say Meadowlark Travel is now selling Oregon-themed products (T-shirts, mugs, etc.) through dealers, and we want “find a dealer” functionality on our website, but we don’t have coordinate information for our dealers, only street addresses. This is where we’ll want to leverage a geocoding API.

Before we start, there are two things to consider. Initially, we’ll probably have some number of dealers already in the database. We’ll want to geocode those dealers in bulk. But what happens in the future when we add new dealers, or dealer addresses change?

As it happens, both cases can be handled with the same code, but there are complications to consider. The first is usage limits. If we have more than 2,500 dealers, we’ll have to break up our initial geocoding over multiple days to avoid Google’s API limits. Also, it may take a long time to do the initial bulk geocoding, and we don’t want our users to have to wait an hour or more to see a map of dealers! After the initial bulk geocoding, however, we can handle new dealers trickling in, as well as dealers who have changed addresses. Let’s start with our dealer model, inmodels/dealer.js:

var mongoose = require('mongoose');

var dealerSchema = mongoose.Schema({

name: String,

address1: String,

address2: String,

city: String,

state: String,

zip: String,

country: String,

phone: String,

website: String,

active: Boolean,

geocodedAddress: String,

lat: Number,

lng: Number,

});

dealerSchema.methods.getAddress = function(lineDelim){

if(!lineDelim) lineDelim = '<br>';

var addr = this.address1;

if(this.address2 && this.address2.match(/\S/))

addr += lineDelim + this.address2;

addr += lineDelim + this.city + ', ' +

this.state + this.zip;

addr += lineDelim + (this.country || 'US');

return addr;

};

var Dealer = mongoose.model("Dealer", dealerSchema);

module.exports = Dealer;

We can populate the database (either by transforming an existing spreadsheet, or manual data entry) and ignore the geocodedAddress, lat, and lng fields. Now that we’ve got the database populated, we can get to the business of geocoding.

We’re going to take an approach similar to what we did for Twitter caching. Since we were caching only 10 tweets, we simply kept the cache in memory. The dealer information could be significantly larger, and we want it cached for speed, but we don’t want to do it in memory. We do, however, want to do it in a way that’s super fast on the client side, so we’re going to create a JSON file with the data.

Let’s go ahead and create our cache:

var dealerCache = {

lastRefreshed: 0,

refreshInterval: 60 * 60 * 1000,

jsonUrl: '/dealers.json',

geocodeLimit: 2000,

geocodeCount: 0,

geocodeBegin: 0,

}

dealerCache.jsonFile = __dirname +

'/public' + dealerCache.jsonUrl;

First we’ll create a helper function that geocodes a given Dealer model and saves the result to the database. Note that if the current address of the dealer matches what was last geocoded, we simply do nothing and return. This method, then, is very fast if the dealer coordinates are up-to-date:

function geocodeDealer(dealer){

var addr = dealer.getAddress(' ');

if(addr===dealer.geocodedAddress) return; // already geocoded

if(dealerCache.geocodeCount >= dealerCache.geocodeLimit){

// has 24 hours passed since we last started geocoding?

if(Date.now() > dealerCache.geocodeCount + 24 * 60 * 60 * 1000){

dealerCache.geocodeBegin = Date.now();

dealerCache.geocodeCount = 0;

} else {

// we can't geocode this now: we've

// reached our usage limit

return;

}

}

geocode(addr, function(err, coords){

if(err) return console.log('Geocoding failure for ' + addr);

dealer.lat = coords.lat;

dealer.lng = coords.lng;

dealer.save();

});

}

NOTE

We could add geocodeDealer as a method of the Dealer model. However, since it has a dependency on our geocoding library, we are opting to make it its own function.

Now we can create a function to refresh the dealer cache. This operation can take a while (especially the first time), but we’ll deal with that in a second:

dealerCache.refresh = function(cb){

if(Date.now() > dealerCache.lastRefreshed + dealerCache.refreshInterval){

// we need to refresh the cache

Dealer.find({ active: true }, function(err, dealers){

if(err) return console.log('Error fetching dealers: '+

err);

// geocodeDealer will do nothing if coordinates are up-to-date

dealers.forEach(geocodeDealer);

// we now write all the dealers out to our cached JSON file

fs.writeFileSync(dealerCache.jsonFile, JSON.stringify(dealers));

// all done -- invoke callback

cb();

});

}

}

Finally, we need to establish a way to routinely keep our cache up-to-date. We could use setInterval, but if a lot of dealers change, it’s possible (if unlikely) that it would take more than an hour to refresh the cache. So instead, when one refresh is done, we have it use setTimeout to wait an hour before refreshing the cache again:

function refreshDealerCacheForever(){

dealerCache.refresh(function(){

// call self after refresh interval

setTimeout(refreshDealerCacheForever,

dealerCache.refreshInterval);

});

}

NOTE

We don’t make refreshDealerCacheForever a method of dealerCache because of a quirk in the way JavaScript handles the this object. In particular, when you invoke a function (not a method), this does not bind to the context of the calling object.

Now we can finally set our plan in motion. When we first start our app, the cache won’t exist, so we simply create an empty one, then start dealerCache.refreshForever:

// create empty cache if it doesn't exist to prevent 404 errors

if(!fs.existsSync(dealerCache.jsonFile)) fs.writeFileSync(JSON.stringify([]));

// start refreshing cache

refreshDealerCacheForever();

Note that the cache file will be updated only after all the dealers have been returned from the database, and any dealers that need to be geocoded have been so. So worst case, if a dealer is added or updated, it will take the refresh interval plus however long it takes to do the geocoding before the updated information shows up on the website.

Displaying a Map

While displaying a map of the dealers really falls under “frontend” work, it would be very disappointing to get this far and not see the fruits of our labor. So we’re going to take a slight departure from the backend focus of this book, and see how to display our newly geocoded dealers on a map.

Unlike the geocoding REST API, using an interactive Google map on your web page requires an API key, which means you’ll have to have a Google account. Instructions for obtaining an API key are found on Google’s API key documentation page.

First we’ll add some CSS styles:

.dealers #map {

width: 100%;

height: 400px;

}

This will create a mobile-friendly map that stretches the width of its container, but has a fixed height. Now that we have some basic styling, we can create a view (views/dealers.handlebars) that displays the dealers on a map, as well as a list of the dealers:

<script src="https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/js?key=YOUR_API_KEY&sensor=false"></script>

<script src="http://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/handlebars.js/1.3.0/handlebars.min.js"></script>

<script id="dealerTemplate" type="text/x-handlebars-template">

\{{#each dealers}}

<div class="dealer">

<h3>\{{name}}</h3>

\{{address1}}<br>

\{{#if address2}}\{{address2}}<br>\{{/if}}

\{{city}}, \{{state}} \{{zip}}<br>

\{{#if country}}\{{country}}<br>\{{/if}}

\{{#if phone}}\{{phone}}<br>\{{/if}}

\{{#if website}}<a href="{{website}}">\{{website}}</a><br>\{{/if}}

</div>

\{{/each}}

</script>

<script>

var map;

var dealerTemplate = Handlebars.compile($('#dealerTemplate').html());

$(document).ready(function(){

// center map on US, set zoom to show whole country

var mapOptions = {

center: new google.maps.LatLng(38.2562, -96.0650),

zoom: 4,

};

// initialize map

map = new google.maps.Map(

document.getElementById('map'),

mapOptions);

// fetch JSON

$.getJSON('/dealers.json', function(dealers){

// add markers on map for each dealer

dealers.forEach(function(dealer){

// skip any dealers without geocoding

if(!dealer.lat || !dealer.lng) return;

var pos = new google.maps.LatLng(dealer.lat, dealer.lng);

var marker = new google.maps.Marker({

position: pos,

map: map,

title: dealer.name

});

});

// update dealer list using Handlebars

$('#dealerList').html(dealerTemplate({ dealers: dealers }));

});

});

</script>

<div class="dealers">

<div id="map"></div>

<div id="dealerList"></div>

</div>

Note that since we wish to use Handlebars on the client side, we have to escape our initial curly braces with a backslash to prevent Handlebars from trying to render the template on the backend. The meat of this bit of code is inside jQuery’s .getJSON helper (where we fetch the /dealers.jsoncache). For each dealer, we create a marker on the map. After we’ve created all the markers, we use Handlebars to update the list of dealers.

Improving Client-Side Performance

Our simple display example works for a small number of dealers. But if you have hundreds of markers to display or more, we can squeeze a little bit more performance out of our display. Currently, we’re parsing the JSON and iterating over it: we could skip that step.

On the server side, instead of (or in addition to) emitting JSON for our dealers, we could emit JavaScript directly:

function dealersToGoogleMaps(dealers){

var js = 'function addMarkers(map){\n' +

'var markers = [];\n' +

'var Marker = google.maps.Marker;\n' +

'var LatLng = google.maps.LatLng;\n';

dealers.forEach(function(d){

var name = d.name.replace(/'/, '\\\'')

.replace(/\\/, '\\\\');

js += 'markers.push(new Marker({\n' +

'\tposition: new LatLng(' +

d.lat + ', ' + d.lng + '),\n' +

'\tmap: map,\n' +

'\ttitle: \'' + name + '\',\n' +

'}));\n';

});

js += '}';

return js;

}

We would then write this JavaScript to a file (/dealers-googleMapMarkers.js, for example), and include that with a <script> tag. Once the map has been initialized, we can just call addMarkers(map), and it will add all of our markers.

The downsides of this approach are that it’s now tied to the choice of Google Maps; if we wanted to switch to Bing, we’d have to rewrite our server-side JavaScript generation. But if maximum speed is needed, this is the way to go. Note that we have to be careful when emitting strings. If we were to simply emit “Paddy’s Bar and Grill,” we would end up with some invalid JavaScript, which would crash our whole page. So whenever you emit a string, make sure to mind what kind of string delimiters you’re using, and escape them. While it’s less common to encounter backslashes in company names, it’s still wise to make sure any backslashes are escaped as well.

Weather Data

Remember our “current weather” widget from Chapter 7? Let’s get that hooked up with some live data! We’ll be using Weather Underground’s free API to get local weather data. You’ll need to create a free account, which you can do at http://www.wunderground.com/weather/api/. Once you have your account set up, you’ll create an API key (once you get an API key, put it in your credentials.js file as WeatherUnderground.ApiKey). Use of the free API is subject to usage restrictions (as I write this, you are allowed no more than 500 requests per day, and no more than 10 per minute). To stay under the free usage restrictions, we’ll cache the data hourly. In your application file, replace the getWeatherData function with the following:

var getWeatherData = (function(){

// our weather cache

var c = {

refreshed: 0,

refreshing: false,

updateFrequency: 360000, // 1 hour

locations: [

{ name: 'Portland' },

{ name: 'Bend' },

{ name: 'Manzanita' },

]

};

return function() {

if( !c.refreshing && Date.now() > c.refreshed + c.updateFrequency ){

c.refreshing = true;

var promises = [];

c.locations.forEach(function(loc){

var deferred = Q.defer();

var url = 'http://api.wunderground.com/api/' +

credentials.WeatherUnderground.ApiKey +

'/conditions/q/OR/' + loc.name + '.json'

http.get(url, function(res){

var body = '';

res.on('data', function(chunk){

body += chunk;

});

res.on('end', function(){

body = JSON.parse(body);

loc.forecastUrl = body.current_observation.forecast_url;

loc.iconUrl = body.current_observation.icon_url;

loc.weather = body.current_observation.weather;

loc.temp = body.current_observation.temperature_string;

deferred.resolve();

});

});

promises.push(deferred);

});

Q.all(promises).then(function(){

c.refreshing = false;

c.refreshed = Date.now();

});

}

return { locations: c.locations };

}

})();

// initialize weather cache

getWeatherData();

If you’re not used to immediately invoked function expressions (IIFEs), this might look pretty strange. Basically, we’re using an IIFE to encapsulate the cache, so we don’t contaminate the global namespace with a lot of variables. The IIFE returns a function, which we save to a variablegetWeatherData, which replaces the previous version that returns dummy data. Note that we have to use promises again because we’re making an HTTP request for each location: because they’re asynchronous, we need a promise to know when all three have finished. We also setc.refreshing to prevent multiple, redundant API calls when the cahce expires. Lastly, we call the function when the server starts up: if we didn’t, the first request wouldn’t be populated.

In this example, we’re keeping our cache in memory, but there’s no reason we couldn’t store the cached data in a database instead, which would lend itself better to scaling out (enabling multiple instances of our server to access the same cached data).

Conclusion

We’ve really only scratched the surface of what can be done with third-party API integration. Everywhere you look, new APIs are popping up, offering every kind of data imaginable (even the City of Portland is now making a lot of public data available through REST APIs). While it would be impossible to cover even a small percentage of the APIs available to you, this chapter has covered the fundamentals you’ll need to know to use these APIs: http.request, https.request, and parsing JSON.