OCA/OCP Java SE 7 Programmer I & II Study Guide (Exams 1Z0-803 & 1Z0-804) (2015)

Appendix A. Serialization

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVES

• Serialization Using the java.io

Package

![]() Two-Minute Drill

Two-Minute Drill

Q&A Self Test

As of summer 2014, the topic of serialization was included in the OCP 7 exam, but not on the OCPJP 5 or OCPJP 6 exams. But this topic was previously on those two exams, and it might get reintroduced at some later date.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVES

Serialization (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

7.2 Use streams to read from and write to files by using classes in the java.io package, including BufferedReader, BufferedWriter, File, FileReader, FileWriter, DataInputStream, DataOutputStream, ObjectOutputStream, ObjectInputStream, and PrintWriter.

Imagine you want to save the state of one or more objects. If Java didn’t have serialization (as the earliest version did not), you’d have to use one of the I/O classes to write out the state of the instance variables of all the objects you want to save. The worst part would be trying to reconstruct new objects that were virtually identical to the objects you were trying to save. You’d need your own protocol for the way in which you wrote and restored the state of each object, or you could end up setting variables with the wrong values. For example, imagine you stored an object that has instance variables for height and weight. At the time you save the state of the object, you could write out the height and weight as two ints in a file, but the order in which you write them is crucial. It would be all too easy to re-create the object but mix up the height and weight values—using the saved height as the value for the new object’s weight and vice versa.

Serialization lets you simply say "save this object and all of its instance variables." Actually it is a little more interesting than that, because you can add, "... unless I’ve explicitly marked a variable as transient, which means, don’t include the transient variable’s value as part of the object’s serialized state."

Working with ObjectOutputStream and ObjectInputStream

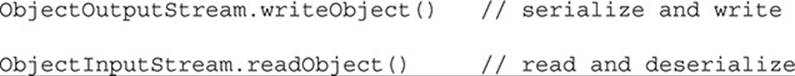

The magic of basic serialization happens with just two methods: one to serialize objects and write them to a stream, and a second to read the stream and deserialize objects.

The java.io.ObjectOutputStream and java.io.ObjectInputStream classes are considered to be higher-level classes in the java.io package, and as we learned earlier, that means that you’ll wrap them around lower-level classes, such as java.io .FileOutputStream andjava.io.FileInputStream. Here’s a small program that creates a (Cat) object, serializes it, and then deserializes it:

Let’s take a look at the key points in this example:

1. We declare that the Cat class implements the Serializable interface. Serializable is a marker interface; it has no methods to implement. (In the next several sections, we’ll cover various rules about when you need to declare classes Serializable.)

2. We make a new Cat object, which as we know is serializable.

3. We serialize the Cat object c by invoking the writeObject() method. It took a fair amount of preparation before we could actually serialize our Cat. First, we had to put all of our I/O-related code in a try/catch block. Next we had to create a FileOutputStream to write the object to. Then we wrapped the FileOutputStream in an ObjectOutputStream, which is the class that has the magic serialization method that we need. Remember that the invocation of writeObject() performs two tasks: it serializes the object, and then it writes the serialized object to a file.

4. We deserialize the Cat object by invoking the readObject() method. The readObject() method returns an Object, so we have to cast the deserialized object back to a Cat. Again, we had to go through the typical I/O hoops to set this up.

This is a bare-bones example of serialization in action. Over the next set of pages we’ll look at some of the more complex issues that are associated with serialization.

Object Graphs

What does it really mean to save an object? If the instance variables are all primitive types, it’s pretty straightforward. But what if the instance variables are themselves references to objects? What gets saved? Clearly in Java it wouldn’t make any sense to save the actual value of a reference variable, because the value of a Java reference has meaning only within the context of a single instance of a JVM. In other words, if you tried to restore the object in another instance of the JVM, even running on the same computer on which the object was originally serialized, the reference would be useless.

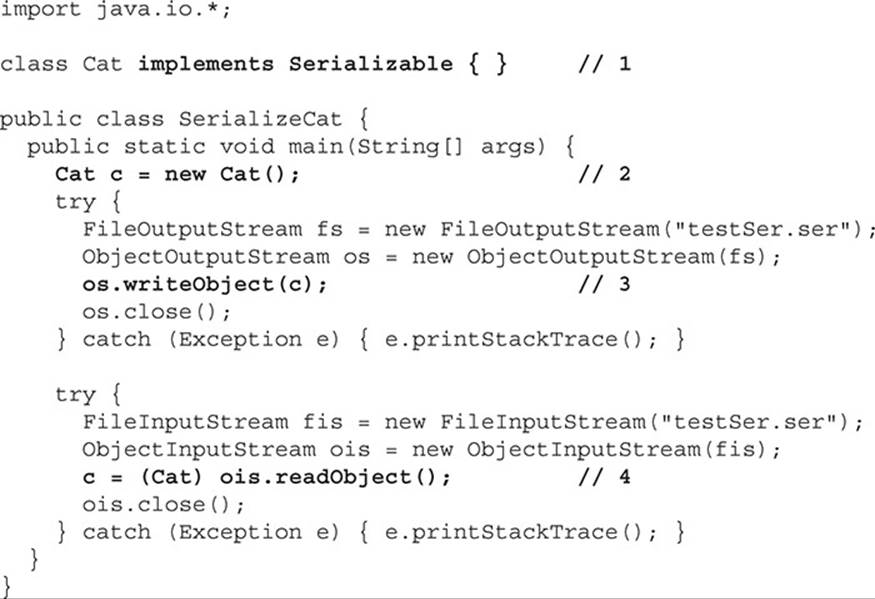

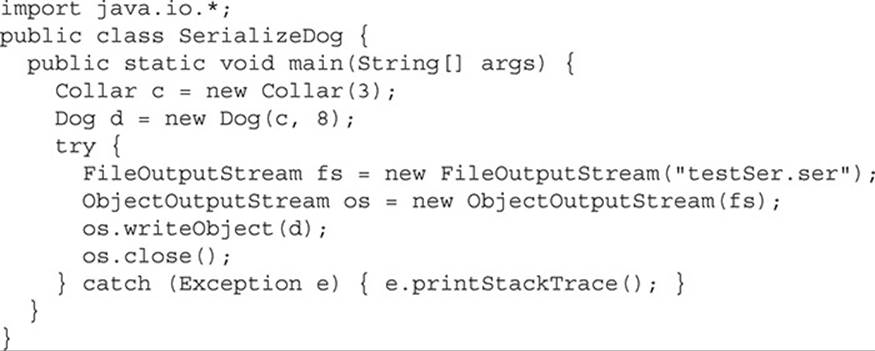

But what about the object that the reference refers to? Look at this class:

Now make a dog… First, you make a Collar for the Dog:

![]()

Then make a new Dog, passing it the Collar:

Dog d = new Dog(c, 8);

Now what happens if you save the Dog? If the goal is to save and then restore a Dog, and the restored Dog is an exact duplicate of the Dog that was saved, then the Dog needs a Collar that is an exact duplicate of the Dog’s Collar at the time the Dog was saved. That means both the Dogand the Collar should be saved.

And what if the Collar itself had references to other objects—like perhaps a Color object? This gets quite complicated very quickly. If it were up to the programmer to know the internal structure of each object the Dog referred to, so that the programmer could be sure to save all the state of all those objects…whew. That would be a nightmare with even the simplest of objects.

Fortunately, the Java serialization mechanism takes care of all of this. When you serialize an object, Java serialization takes care of saving that object’s entire "object graph." That means a deep copy of everything the saved object needs to be restored. For example, if you serialize aDog object, the Collar will be serialized automatically. And if the Collar class contained a reference to another object, THAT object would also be serialized, and so on. And the only object you have to worry about saving and restoring is the Dog. The other objects required to fully reconstruct that Dog are saved (and restored) automatically through serialization.

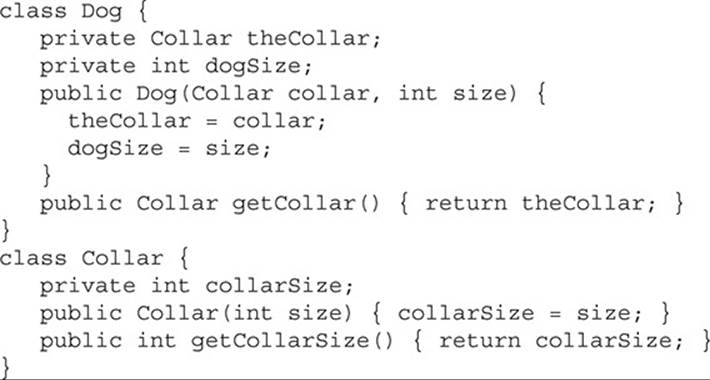

Remember, you do have to make a conscious choice to create objects that are serializable, by implementing the Serializable interface. If we want to save Dog objects, for example, we’ll have to modify the Dog class as follows:

And now we can save the Dog with the following code:

But when we run this code we get a runtime exception something like this

![]()

What did we forget? The Collar class must ALSO be Serializable. If we modify the Collar class and make it serializable, then there’s no problem:

class Collar implements Serializable {

// same

}

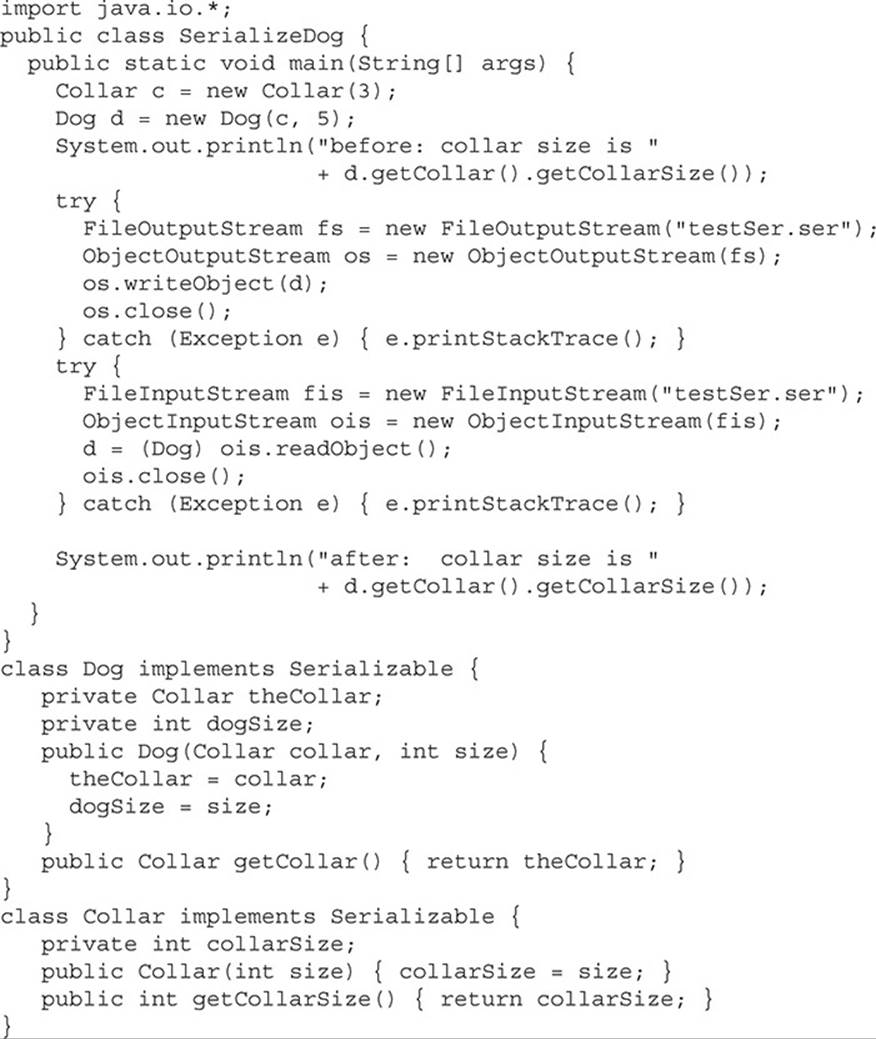

Here’s the complete listing:

This produces the output:

![]()

But what would happen if we didn’t have access to the Collar class source code? In other words, what if making the Collar class serializable was not an option? Are we stuck with a non-serializable Dog?

Obviously we could subclass the Collar class, mark the subclass as Serializable, and then use the Collar subclass instead of the Collar class. But that’s not always an option either for several potential reasons:

1. The Collar class might be final, preventing subclassing.

OR

2. The Collar class might itself refer to other non-serializable objects, and without knowing the internal structure of Collar, you aren’t able to make all these fixes (assuming you even wanted to TRY to go down that road).

OR

3. Subclassing is not an option for other reasons related to your design.

So…THEN what do you do if you want to save a Dog?

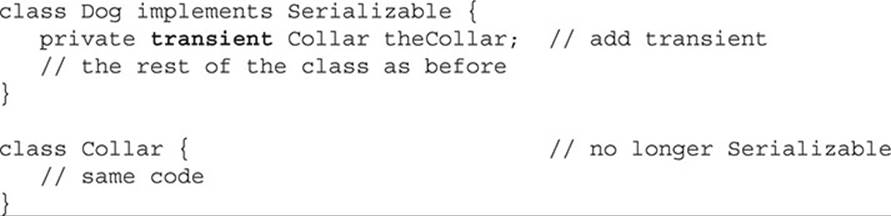

That’s where the transient modifier comes in. If you mark the Dog’s Collar instance variable with transient, then serialization will simply skip the Collar during serialization:

Now we have a Serializable Dog, with a non-serializable Collar, but the Dog has marked the Collar transient; the output is

![]()

So NOW what can we do?

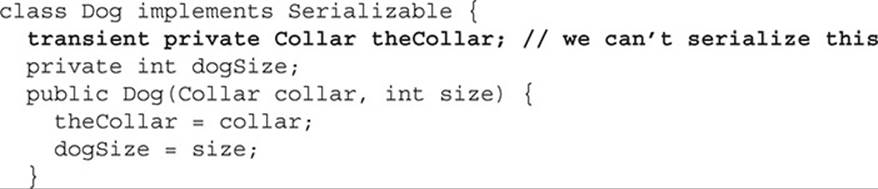

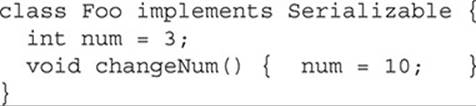

Using writeObject and readObject

Consider the problem: we have a Dog object we want to save. The Dog has a Collar, and the Collar has state that should also be saved as part of the Dog’s state. But… the Collar is not Serializable, so we must mark it transient. That means when the Dog is deserialized, it comes back with a null Collar. What can we do to somehow make sure that when the Dog is deserialized, it gets a new Collar that matches the one the Dog had when the Dog was saved?

Java serialization has a special mechanism just for this—a set of private methods you can implement in your class that, if present, will be invoked automatically during serialization and deserialization. It’s almost as if the methods were defined in the Serializable interface, except they aren’t. They are part of a special callback contract the serialization system offers you that basically says, "If you (the programmer) have a pair of methods matching this exact signature (you’ll see them in a moment), these methods will be called during the serialization/deserialization process."

These methods let you step into the middle of serialization and deserialization. So they’re perfect for letting you solve the Dog/Collar problem: when a Dog is being saved, you can step into the middle of serialization and say, "By the way, I’d like to add the state of the Collar’s variable (an int) to the stream when the Dog is serialized." You’ve manually added the state of the Collar to the Dog’s serialized representation, even though the Collar itself is not saved.

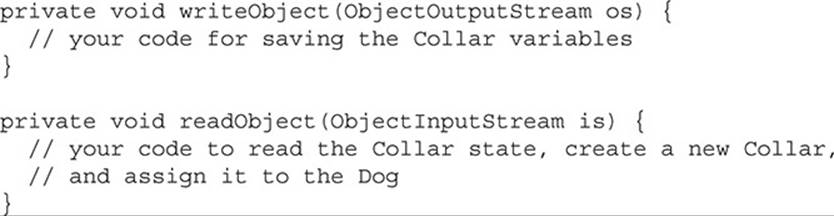

Of course, you’ll need to restore the Collar during deserialization by stepping into the middle and saying, "I’ll read that extra int I saved to the Dog stream, and use it to create a new Collar, and then assign that new Collar to the Dog that’s being deserialized." The two special methods you define must have signatures that look EXACTLY like this:

Yes, we’re going to write methods that have the same name as the ones we’ve been calling! Where do these methods go? Let’s change the Dog class:

Let’s take a look at the preceding code.

In our scenario we’ve agreed that, for whatever real-world reason, we can’t serialize a Collar object, but we want to serialize a Dog. To do this we’re going to implement writeObject() and readObject(). By implementing these two methods you’re saying to the compiler: "If anyone invokes writeObject() or readObject() concerning a Dog object, use this code as part of the read and write."

1. Like most I/O-related methods writeObject() can throw exceptions. You can declare them or handle them but we recommend handling them.

2. When you invoke defaultWriteObject() from within writeObject() you’re telling the JVM to do the normal serialization process for this object. When implementing writeObject(), you will typically request the normal serialization process, and do some custom writing and reading too.

3. In this case we decided to write an extra int (the collar size) to the stream that’s creating the serialized Dog. You can write extra stuff before and/or after you invoke defaultWriteObject(). BUT…when you read it back in, you have to read the extra stuff in the same order you wrote it.

4. Again, we chose to handle rather than declare the exceptions.

5. When it’s time to deserialize, defaultReadObject() handles the normal deserialization you’d get if you didn’t implement a readObject() method.

6. Finally we build a new Collar object for the Dog using the collar size that we manually serialized. (We had to invoke readInt() after we invoked defaultReadObject() or the streamed data would be out of sync!)

Remember, the most common reason to implement writeObject() and readObject() is when you have to save some part of an object’s state manually. If you choose, you can write and read ALL of the state yourself, but that’s very rare. So, when you want to do only a part of the serialization/deserialization yourself, you MUST invoke the defaultReadObject() and defaultWriteObject() methods to do the rest.

Which brings up another question—why wouldn’t all Java classes be serializable? Why isn’t class Object serializable? There are some things in Java that simply cannot be serialized because they are runtime specific. Things like streams, threads, runtime, etc. and even some GUI classes (which are connected to the underlying OS) cannot be serialized. What is and is not serializable in the Java API is NOT part of the exam, but you’ll need to keep them in mind if you’re serializing complex objects.

How Inheritance Affects Serialization

Serialization is very cool, but in order to apply it effectively you’re going to have to understand how your class’s superclasses affect serialization.

If a superclass is Serializable, then according to normal Java interface rules, all subclasses of that class automatically implement Serializable implicitly. In other words, a subclass of a class marked Serializable passes the IS-A test for Serializable, and thus can be saved without having to explicitly mark the subclass as Serializable. You simply cannot tell whether a class is or is not Serializable UNLESS you can see the class inheritance tree to see if any other superclasses implement Serializable. If the class does not explicitly extend any other class, and does not implement Serializable, then you know for CERTAIN that the class is not Serializable, because class Object does NOT implement Serializable.

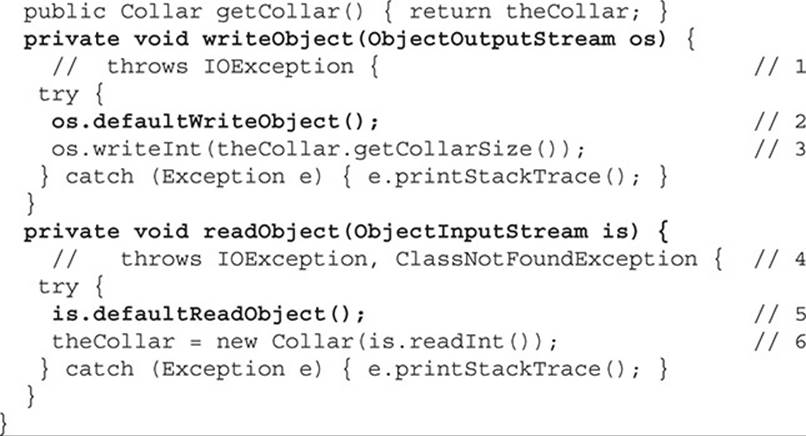

That brings up another key issue with serialization…what happens if a superclass is not marked Serializable, but the subclass is? Can the subclass still be serialized even if its superclass does not implement Serializable? Imagine this:

Now you have a Serializable Dog class, with a non-Serializable superclass. This works! But there are potentially serious implications. To fully understand those implications, let’s step back and look at the difference between an object that comes from deserialization vs. an object created using new. Remember, when an object is constructed using new (as opposed to being deserialized), the following things happen (in this order):

1. All instance variables are assigned default values.

2. The constructor is invoked, which immediately invokes the superclass constructor (or another overloaded constructor, until one of the overloaded constructors invokes the superclass constructor).

3. All superclass constructors complete.

4. Instance variables that are initialized as part of their declaration are assigned their initial value (as opposed to the default values they’re given prior to the superclass constructors completing).

5. The constructor completes.

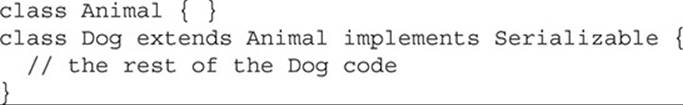

But these things do NOT happen when an object is deserialized. When an instance of a serializable class is deserialized, the constructor does not run, and instance variables are NOT given their initially assigned values! Think about it—if the constructor were invoked, and/or instance variables were assigned the values given in their declarations, the object you’re trying to restore would revert back to its original state, rather than coming back reflecting the changes in its state that happened sometime after it was created. For example, imagine you have a class that declares an instance variable and assigns it the int value 3, and includes a method that changes the instance variable value to 10:

Obviously if you serialize a Foo instance after the changeNum() method runs, the value of the num variable should be 10. When the Foo instance is deserialized, you want the num variable to still be 10! You obviously don’t want the initialization (in this case, the assignment of the value3 to the variable num) to happen. Think of constructors and instance variable assignments together as part of one complete object initialization process (and in fact, they DO become one initialization method in the bytecode). The point is, when an object is deserialized we do NOT want any of the normal initialization to happen. We don’t want the constructor to run, and we don’t want the explicitly declared values to be assigned. We want only the values saved as part of the serialized state of the object to be reassigned.

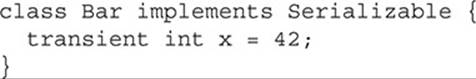

Of course if you have variables marked transient, they will not be restored to their original state (unless you implement readObject()), but will instead be given the default value for that data type. In other words, even if you say

when the Bar instance is deserialized, the variable x will be set to a value of 0. Object references marked transient will always be reset to null, regardless of whether they were initialized at the time of declaration in the class.

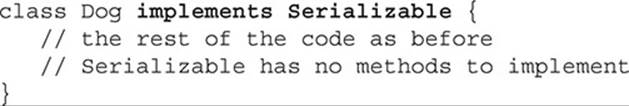

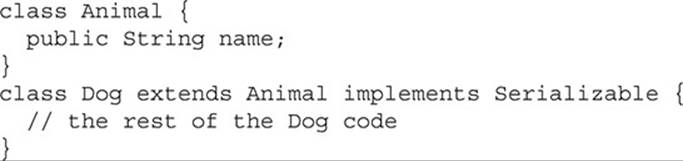

So, that’s what happens when the object is deserialized, and the class of the serialized object directly extends Object, or has ONLY serializable classes in its inheritance tree. It gets a little trickier when the serializable class has one or more non-serializable superclasses. Getting back to our non-serializable Animal class with a serializable Dog subclass example:

Because Animal is NOT serializable, any state maintained in the Animal class, even though the state variable is inherited by the Dog, isn’t going to be restored with the Dog when it’s deserialized! The reason is, the (unserialized) Animal part of the Dog is going to be reinitialized just as it would be if you were making a new Dog (as opposed to deserializing one). That means all the things that happen to an object during construction, will happen—but only to the Animal parts of a Dog. In other words, the instance variables from the Dog’s class will be serialized and deserialized correctly, but the inherited variables from the non-serializable Animal superclass will come back with their default/initially assigned values rather than the values they had at the time of serialization.

If you are a serializable class, but your superclass is NOT serializable, then any instance variables you INHERIT from that superclass will be reset to the values they were given during the original construction of the object. This is because the non-serializable class constructor WILL run!

In fact, every constructor ABOVE the first non-serializable class constructor will also run, no matter what, because once the first super constructor is invoked (during deserialization), it of course invokes its super constructor and so on up the inheritance tree.

For the exam, you’ll need to be able to recognize which variables will and will not be restored with the appropriate values when an object is deserialized, so be sure to study the following code example and the output:

which produces the output:

![]()

The key here is that because Animal is not serializable, when the Dog was deserialized, the Animal constructor ran and reset the Dog’s inherited weight variable.

If you serialize a collection or an array, every element must be serializable! A single non-serializable element will cause serialization to fail. Note also that while the collection interfaces are not serializable, the concrete collection classes in the Java API are.

Serialization Is Not for Statics

Finally, you might notice that we’ve talked ONLY about instance variables, not static variables. Should static variables be saved as part of the object’s state? Isn’t the state of a static variable at the time an object was serialized important? Yes and no. It might be important, but it isn’t part of the instance’s state at all. Remember, you should think of static variables purely as CLASS variables. They have nothing to do with individual instances. But serialization applies only to OBJECTS. And what happens if you deserialize three different Dog instances, all of which were serialized at different times, and all of which were saved when the value of a static variable in class Dog was different. Which instance would "win"? Which instance’s static value would be used to replace the one currently in the one and only Dog class that’s currently loaded? See the problem?

Static variables are NEVER saved as part of the object’s state…because they do not belong to the object!

What about DataInputStream and DataOutputStream ? They’re in the objectives! It turns out that while the exam was being created, it was decided that those two classes wouldn’t be on the exam after all, but someone forgot to remove them from the objectives! So you get a break. That’s one less thing you’ll have to worry about.

As simple as serialization code is to write, versioning problems can occur in the real world. If you save aDogobject using one version of the class, but attempt to deserialize it using a newer, different version of the class, deserialization might fail. See the Java API for details about versioning issues and solutions.

CERTIFICATION SUMMARY

Serialization lets you save, ship, and restore everything you need to know about a live object. And when your object points to other objects, they get saved too. The java.io.ObjectOutputStream and java.io.ObjectInputStream classes are used to serialize and deserialize objects. Typically you wrap them around instances of FileOutputStream and FileInputStream, respectively.

The key method you invoke to serialize an object is writeObject(), and to deserialize an object invoke readObject(). In order to serialize an object, it must implement the Serializable interface. Mark instance variables transient if you don’t want their state to be part of the serialization process. You can augment the serialization process for your class by implementing writeObject() and readObject(). If you do that, an embedded call to defaultReadObject() and defaultWriteObject() will handle the normal serialization tasks, and you can augment those invocations with manual reading from and writing to the stream.

If a superclass implements Serializable then all of its subclasses do too. If a superclass doesn’t implement Serializable, then when a subclass object is deserialized the non-serializable superclass’s constructor runs—be careful! Finally, remember that serialization is about instances, so static variables aren’t serialized.

![]() TWO-MINUTE DRILL

TWO-MINUTE DRILL

Here are some of the key points from the certification objectives in this appendix.

Serialization (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

![]() The classes you need to understand are all in the java.io package; they include: ObjectOutputStream and ObjectInputStream primarily, and FileOutputStream and FileInputStream because you will use them to create the low-level streams that the ObjectXxxStream classes will use.

The classes you need to understand are all in the java.io package; they include: ObjectOutputStream and ObjectInputStream primarily, and FileOutputStream and FileInputStream because you will use them to create the low-level streams that the ObjectXxxStream classes will use.

![]() A class must implement Serializable before its objects can be serialized.

A class must implement Serializable before its objects can be serialized.

![]() The ObjectOutputStream.writeObject() method serializes objects, and the ObjectInputStream.readObject() method deserializes objects.

The ObjectOutputStream.writeObject() method serializes objects, and the ObjectInputStream.readObject() method deserializes objects.

![]() If you mark an instance variable transient, it will not be serialized even though the rest of the object’s state will be.

If you mark an instance variable transient, it will not be serialized even though the rest of the object’s state will be.

![]() You can supplement a class’s automatic serialization process by implementing the writeObject() and readObject() methods. If you do this, embedding calls to defaultWriteObject() and defaultReadObject(), respectively, will handle the part of serialization that happens normally.

You can supplement a class’s automatic serialization process by implementing the writeObject() and readObject() methods. If you do this, embedding calls to defaultWriteObject() and defaultReadObject(), respectively, will handle the part of serialization that happens normally.

![]() If a superclass implements Serializable, then its subclasses do automatically.

If a superclass implements Serializable, then its subclasses do automatically.

![]() If a superclass doesn’t implement Serializable, then when a subclass object is deserialized, the superclass constructor will be invoked, along with its superconstructor(s).

If a superclass doesn’t implement Serializable, then when a subclass object is deserialized, the superclass constructor will be invoked, along with its superconstructor(s).

![]() DataInputStream and DataOutputStream aren’t actually on the exam, in spite of what the Oracle objectives say.

DataInputStream and DataOutputStream aren’t actually on the exam, in spite of what the Oracle objectives say.

SELF TEST

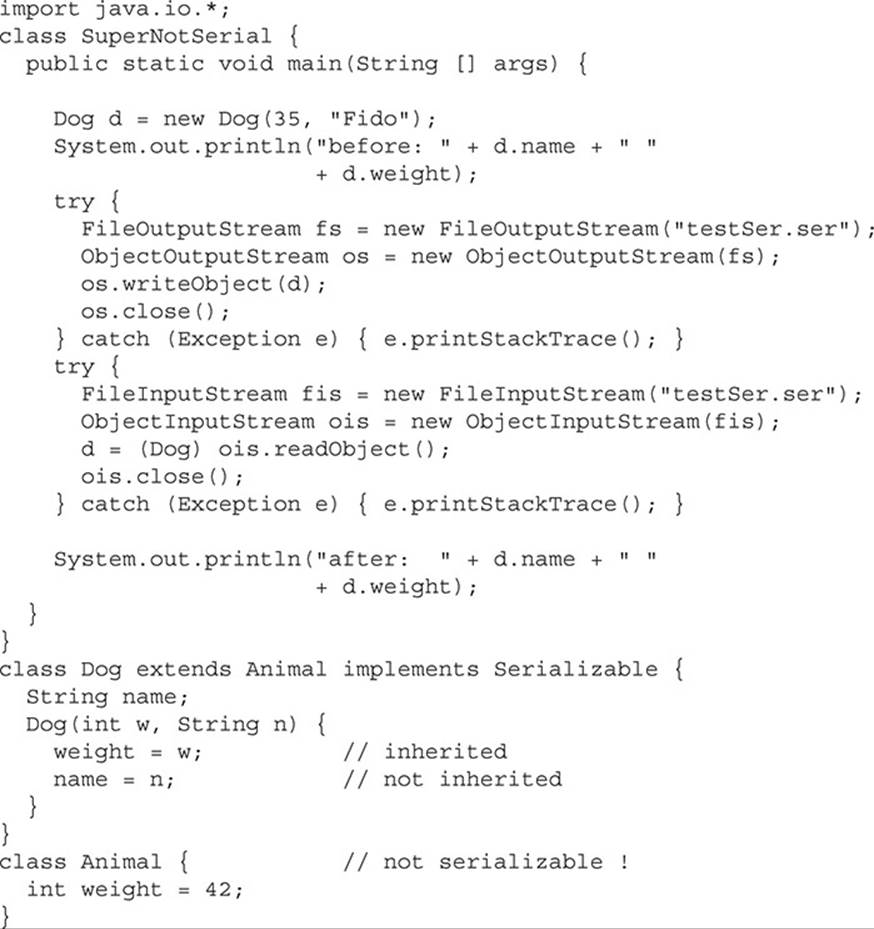

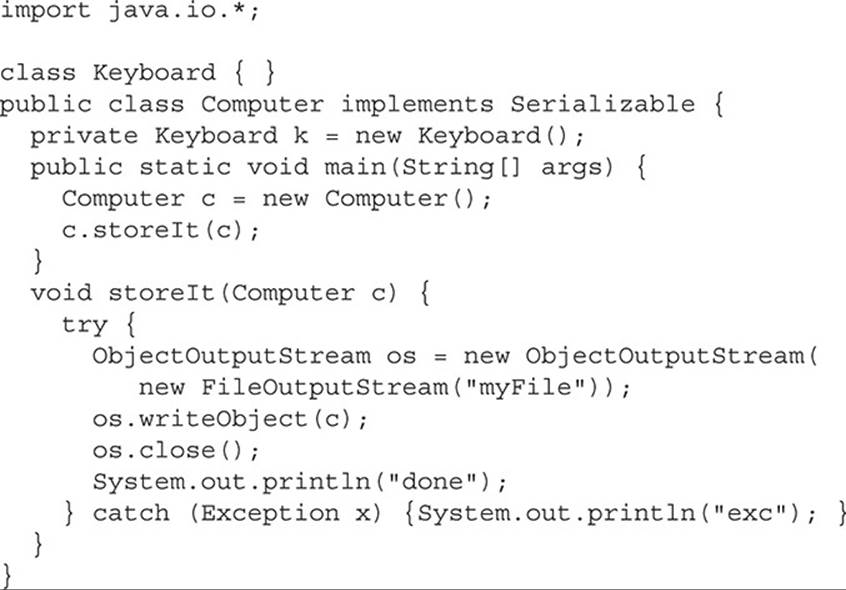

1. Given:

What is the result?

A. pc

B. pcc

C. pcp

D. pcpc

E. Compilation fails

F. An exception is thrown at runtime

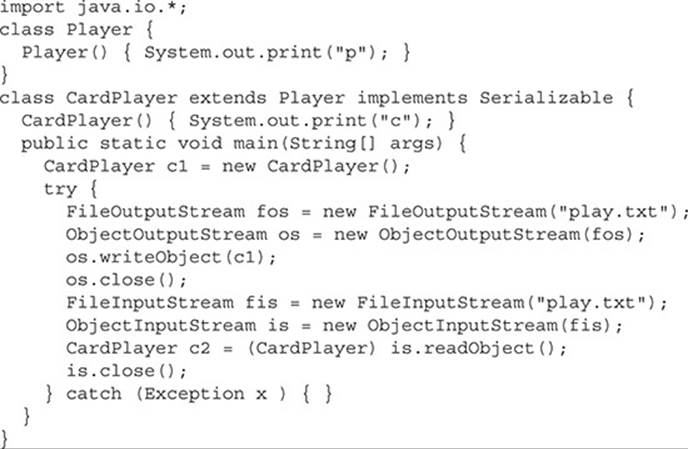

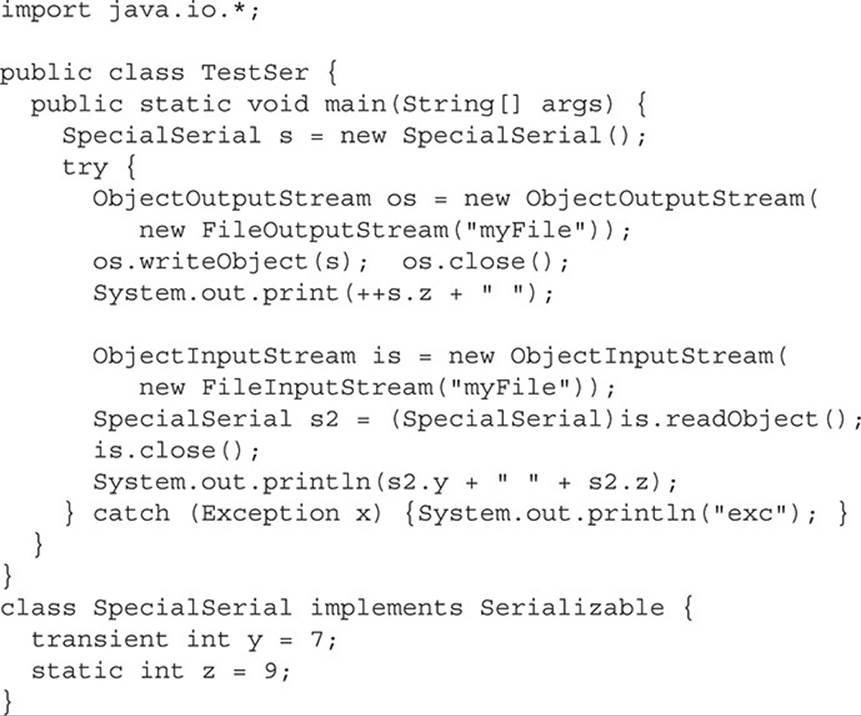

2. Given:

What is the result? (Choose all that apply.)

A. exc

B. done

C. Compilation fails

D. Exactly one object is serialized

E. Exactly two objects are serialized

3. Given:

Which are true? (Choose all that apply.)

A. Compilation fails

B. The output is 10 0 9

C. The output is 10 0 10

D. The output is 10 7 9

E. The output is 10 7 10

F. In order to alter the standard deserialization process you would implement the readObject() method in SpecialSerial

G. In order to alter the standard deserialization process you would implement the defaultReadObject() method in SpecialSerial

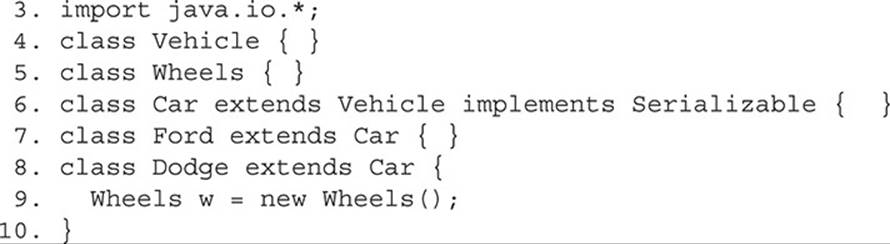

4. Given:

Instances of which class(es) can be serialized? (Choose all that apply.)

A. Car

B. Ford

C. Dodge

D Wheels

E. Vehicle

SELF TEST ANSWERS

1. ![]() C is correct. It’s okay for a class to implement Serializable even if its superclass doesn’t. However, when you deserialize such an object, the non-serializable superclass must run its constructor. Remember, constructors don’t run on deserialized classes that implementSerializable.

C is correct. It’s okay for a class to implement Serializable even if its superclass doesn’t. However, when you deserialize such an object, the non-serializable superclass must run its constructor. Remember, constructors don’t run on deserialized classes that implementSerializable.

![]() A, B, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

A, B, D, E, and F are incorrect based on the above. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

2. ![]() A is correct. An instance of type Computer Has-a Keyboard. Because Keyboard doesn’t implement Serializable, any attempt to serialize an instance of Computer will cause an exception to be thrown.

A is correct. An instance of type Computer Has-a Keyboard. Because Keyboard doesn’t implement Serializable, any attempt to serialize an instance of Computer will cause an exception to be thrown.

![]() B, C, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. If Keyboard did implement Serializable then two objects would have been serialized. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

B, C, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. If Keyboard did implement Serializable then two objects would have been serialized. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

3. ![]() C and F are correct. C is correct because static and transient variables are not serialized when an object is serialized. F is a valid statement.

C and F are correct. C is correct because static and transient variables are not serialized when an object is serialized. F is a valid statement.

![]() A, B, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. G is incorrect because you don’t implement the defaultReadObject() method, you call it from within the readObject() method, along with any custom read operations your class needs. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

A, B, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. G is incorrect because you don’t implement the defaultReadObject() method, you call it from within the readObject() method, along with any custom read operations your class needs. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

4. ![]() A and B are correct. Dodge instances cannot be serialized because they "have" an instance of Wheels, which is not serializable. Vehicle instances cannot be serialized even though the subclass Car can be.

A and B are correct. Dodge instances cannot be serialized because they "have" an instance of Wheels, which is not serializable. Vehicle instances cannot be serialized even though the subclass Car can be.

![]() C, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

C, D, and E are incorrect based on the above. (OCP 7 Objective 7.2)

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.