The Go Programming Language (2016)

4. Composite Types

In Chapter 3 we discussed the basic types that serve as building blocks for data structures in a Go program; they are the atoms of our universe. In this chapter, we’ll take a look at composite types, the molecules created by combining the basic types in various ways. We’ll talk about four such types—arrays, slices, maps, and structs—and at the end of the chapter, we’ll show how structured data using these types can be encoded as and parsed from JSON data and used to generate HTML from templates.

Arrays and structs are aggregate types; their values are concatenations of other values in memory. Arrays are homogeneous—their elements all have the same type—whereas structs are heterogeneous. Both arrays and structs are fixed size. In contrast, slices and maps are dynamic data structures that grow as values are added.

4.1 Arrays

An array is a fixed-length sequence of zero or more elements of a particular type. Because of their fixed length, arrays are rarely used directly in Go. Slices, which can grow and shrink, are much more versatile, but to understand slices we must understand arrays first.

Individual array elements are accessed with the conventional subscript notation, where subscripts run from zero to one less than the array length. The built-in function len returns the number of elements in the array.

var a [3]int // array of 3 integers

fmt.Println(a[0]) // print the first element

fmt.Println(a[len(a)-1]) // print the last element, a[2]

// Print the indices and elements.

for i, v := range a {

fmt.Printf("%d %d\n", i, v)

}

// Print the elements only.

for _, v := range a {

fmt.Printf("%d\n", v)

}

By default, the elements of a new array variable are initially set to the zero value for the element type, which is 0 for numbers. We can use an array literal to initialize an array with a list of values:

var q [3]int = [3]int{1, 2, 3}

var r [3]int = [3]int{1, 2}

fmt.Println(r[2]) // "0"

In an array literal, if an ellipsis “...” appears in place of the length, the array length is determined by the number of initializers. The definition of q can be simplified to

q := [...]int{1, 2, 3}

fmt.Printf("%T\n", q) // "[3]int"

The size of an array is part of its type, so [3]int and [4]int are different types. The size must be a constant expression, that is, an expression whose value can be computed as the program is being compiled.

q := [3]int{1, 2, 3}

q = [4]int{1, 2, 3, 4} // compile error: cannot assign [4]int to [3]int

As we’ll see, the literal syntax is similar for arrays, slices, maps, and structs. The specific form above is a list of values in order, but it is also possible to specify a list of index and value pairs, like this:

type Currency int

const (

USD Currency = iota

EUR

GBP

RMB

)

symbol := [...]string{USD: "$", EUR: "€", GBP: "£", RMB: "¥"}

fmt.Println(RMB, symbol[RMB]) // "3 ¥"

In this form, indices can appear in any order and some may be omitted; as before, unspecified values take on the zero value for the element type. For instance,

r := [...]int{99: -1}

defines an array r with 100 elements, all zero except for the last, which has value −1.

If an array’s element type is comparable then the array type is comparable too, so we may directly compare two arrays of that type using the == operator, which reports whether all corresponding elements are equal. The != operator is its negation.

a := [2]int{1, 2}

b := [...]int{1, 2}

c := [2]int{1, 3}

fmt.Println(a == b, a == c, b == c) // "true false false"

d := [3]int{1, 2}

fmt.Println(a == d) // compile error: cannot compare [2]int == [3]int

As a more plausible example, the function Sum256 in the crypto/sha256 package produces the SHA256 cryptographic hash or digest of a message stored in an arbitrary byte slice. The digest has 256 bits, so its type is [32]byte. If two digests are the same, it is extremely likely that the two messages are the same; if the digests differ, the two messages are different. This program prints and compares the SHA256 digests of "x" and "X":

gopl.io/ch4/sha256

import "crypto/sha256"

func main() {

c1 := sha256.Sum256([]byte("x"))

c2 := sha256.Sum256([]byte("X"))

fmt.Printf("%x\n%x\n%t\n%T\n", c1, c2, c1 == c2, c1)

// Output:

// 2d711642b726b04401627ca9fbac32f5c8530fb1903cc4db02258717921a4881

// 4b68ab3847feda7d6c62c1fbcbeebfa35eab7351ed5e78f4ddadea5df64b8015

// false

// [32]uint8

}

The two inputs differ by only a single bit, but approximately half the bits are different in the digests. Notice the Printf verbs: %x to print all the elements of an array or slice of bytes in hexadecimal, %t to show a boolean, and %T to display the type of a value.

When a function is called, a copy of each argument value is assigned to the corresponding parameter variable, so the function receives a copy, not the original. Passing large arrays in this way can be inefficient, and any changes that the function makes to array elements affect only the copy, not the original. In this regard, Go treats arrays like any other type, but this behavior is different from languages that implicitly pass arrays by reference.

Of course, we can explicitly pass a pointer to an array so that any modifications the function makes to array elements will be visible to the caller. This function zeroes the contents of a [32]byte array:

func zero(ptr *[32]byte) {

for i := range ptr {

ptr[i] = 0

}

}

The array literal [32]byte{} yields an array of 32 bytes. Each element of the array has the zero value for byte, which is zero. We can use that fact to write a different version of zero:

func zero(ptr *[32]byte) {

*ptr = [32]byte{}

}

Using a pointer to an array is efficient and allows the called function to mutate the caller’s variable, but arrays are still inherently inflexible because of their fixed size. The zero function will not accept a pointer to a [16]byte variable, for example, nor is there any way to add or remove array elements. For these reasons, other than special cases like SHA256’s fixed-size hash, arrays are seldom used as function parameters; instead, we use slices.

Exercise 4.1: Write a function that counts the number of bits that are different in two SHA256 hashes. (See PopCount from Section 2.6.2.)

Exercise 4.2: Write a program that prints the SHA256 hash of its standard input by default but supports a command-line flag to print the SHA384 or SHA512 hash instead.

4.2 Slices

Slices represent variable-length sequences whose elements all have the same type. A slice type is written []T, where the elements have type T; it looks like an array type without a size.

Arrays and slices are intimately connected. A slice is a lightweight data structure that gives access to a subsequence (or perhaps all) of the elements of an array, which is known as the slice’s underlying array. A slice has three components: a pointer, a length, and a capacity. The pointer points to the first element of the array that is reachable through the slice, which is not necessarily the array’s first element. The length is the number of slice elements; it can’t exceed the capacity, which is usually the number of elements between the start of the slice and the end of the underlying array. The built-in functions len and cap return those values.

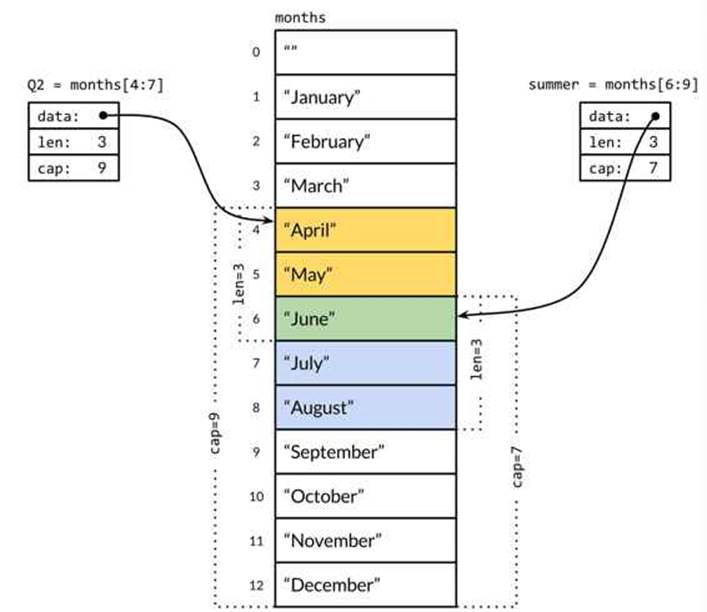

Figure 4.1. Two overlapping slices of an array of months.

Multiple slices can share the same underlying array and may refer to overlapping parts of that array. Figure 4.1 shows an array of strings for the months of the year, and two overlapping slices of it. The array is declared as

months := [...]string{1: "January", /* ... */, 12: "December"}

so January is months[1] and December is months[12]. Ordinarily, the array element at index 0 would contain the first value, but because months are always numbered from 1, we can leave it out of the declaration and it will be initialized to an empty string.

The slice operator s[i:j], where 0 ≤ i ≤ j ≤ cap(s), creates a new slice that refers to elements i through j-1 of the sequence s, which may be an array variable, a pointer to an array, or another slice. The resulting slice has j-i elements. If i is omitted, it’s 0, and if j is omitted, it’slen(s). Thus the slice months[1:13] refers to the whole range of valid months, as does the slice months[1:]; the slice months[:] refers to the whole array. Let’s define overlapping slices for the second quarter and the northern summer:

Q2 := months[4:7]

summer := months[6:9]

fmt.Println(Q2) // ["April" "May" "June"]

fmt.Println(summer) // ["June" "July" "August"]

June is included in each and is the sole output of this (inefficient) test for common elements:

for _, s := range summer {

for _, q := range Q2 {

if s == q {

fmt.Printf("%s appears in both\n", s)

}

}

}

Slicing beyond cap(s) causes a panic, but slicing beyond len(s) extends the slice, so the result may be longer than the original:

fmt.Println(summer[:20]) // panic: out of range

endlessSummer := summer[:5] // extend a slice (within capacity)

fmt.Println(endlessSummer) // "[June July August September October]"

As an aside, note the similarity of the substring operation on strings to the slice operator on []byte slices. Both are written x[m:n], and both return a subsequence of the original bytes, sharing the underlying representation so that both operations take constant time. The expressionx[m:n] yields a string if x is a string, or a []byte if x is a []byte.

Since a slice contains a pointer to an element of an array, passing a slice to a function permits the function to modify the underlying array elements. In other words, copying a slice creates an alias (§2.3.2) for the underlying array. The function reverse reverses the elements of an []intslice in place, and it may be applied to slices of any length.

gopl.io/ch4/rev

// reverse reverses a slice of ints in place.

func reverse(s []int) {

for i, j := 0, len(s)-1; i < j; i, j = i+1, j-1 {

s[i], s[j] = s[j], s[i]

}

}

Here we reverse the whole array a:

a := [...]int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

reverse(a[:])

fmt.Println(a) // "[5 4 3 2 1 0]"

A simple way to rotate a slice left by n elements is to apply the reverse function three times, first to the leading n elements, then to the remaining elements, and finally to the whole slice. (To rotate to the right, make the third call first.)

s := []int{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

// Rotate s left by two positions.

reverse(s[:2])

reverse(s[2:])

reverse(s)

fmt.Println(s) // "[2 3 4 5 0 1]"

Notice how the expression that initializes the slice s differs from that for the array a. A slice literal looks like an array literal, a sequence of values separated by commas and surrounded by braces, but the size is not given. This implicitly creates an array variable of the right size and yields a slice that points to it. As with array literals, slice literals may specify the values in order, or give their indices explicitly, or use a mix of the two styles.

Unlike arrays, slices are not comparable, so we cannot use == to test whether two slices contain the same elements. The standard library provides the highly optimized bytes.Equal function for comparing two slices of bytes ([]byte), but for other types of slice, we must do the comparison ourselves:

func equal(x, y []string) bool {

if len(x) != len(y) {

return false

}

for i := range x {

if x[i] != y[i] {

return false

}

}

return true

}

Given how natural this “deep” equality test is, and that it is no more costly at run time than the == operator for arrays of strings, it may be puzzling that slice comparisons do not also work this way. There are two reasons why deep equivalence is problematic. First, unlike array elements, the elements of a slice are indirect, making it possible for a slice to contain itself. Although there are ways to deal with such cases, none is simple, efficient, and most importantly, obvious.

Second, because slice elements are indirect, a fixed slice value may contain different elements at different times as the contents of the underlying array are modified. Because a hash table such as Go’s map type makes only shallow copies of its keys, it requires that equality for each key remain the same throughout the lifetime of the hash table. Deep equivalence would thus make slices unsuitable for use as map keys. For reference types like pointers and channels, the == operator tests reference identity, that is, whether the two entities refer to the same thing. An analogous “shallow” equality test for slices could be useful, and it would solve the problem with maps, but the inconsistent treatment of slices and arrays by the == operator would be confusing. The safest choice is to disallow slice comparisons altogether.

The only legal slice comparison is against nil, as in

if summer == nil { /* ... */ }

The zero value of a slice type is nil. A nil slice has no underlying array. The nil slice has length and capacity zero, but there are also non-nil slices of length and capacity zero, such as []int{} or make([]int, 3)[3:]. As with any type that can have nil values, the nil value of a particular slice type can be written using a conversion expression such as []int(nil).

var s []int // len(s) == 0, s == nil

s = nil // len(s) == 0, s == nil

s = []int(nil) // len(s) == 0, s == nil

s = []int{} // len(s) == 0, s != nil

So, if you need to test whether a slice is empty, use len(s) == 0, not s == nil. Other than comparing equal to nil, a nil slice behaves like any other zero-length slice; reverse(nil) is perfectly safe, for example. Unless clearly documented to the contrary, Go functions should treat all zero-length slices the same way, whether nil or non-nil.

The built-in function make creates a slice of a specified element type, length, and capacity. The capacity argument may be omitted, in which case the capacity equals the length.

make([]T, len)

make([]T, len, cap) // same as make([]T, cap)[:len]

Under the hood, make creates an unnamed array variable and returns a slice of it; the array is accessible only through the returned slice. In the first form, the slice is a view of the entire array. In the second, the slice is a view of only the array’s first len elements, but its capacity includes the entire array. The additional elements are set aside for future growth.

4.2.1 The append Function

The built-in append function appends items to slices:

var runes []rune

for _, r := range "Hello, ![]() " {

" {

runes = append(runes, r)

}

fmt.Printf("%q\n", runes) // "['H' 'e' 'l' 'l' 'o' ',' ' ' '![]() ' '

' '![]() ']"

']"

The loop uses append to build the slice of nine runes encoded by the string literal, although this specific problem is more conveniently solved by using the built-in conversion []rune("Hello, ![]() ").

").

The append function is crucial to understanding how slices work, so let’s take a look at what is going on. Here’s a version called appendInt that is specialized for []int slices:

gopl.io/ch4/append

func appendInt(x []int, y int) []int {

var z []int

zlen := len(x) + 1

if zlen <= cap(x) {

// There is room to grow. Extend the slice.

z = x[:zlen]

} else {

// There is insufficient space. Allocate a new array.

// Grow by doubling, for amortized linear complexity.

zcap := zlen

if zcap < 2*len(x) {

zcap = 2 * len(x)

}

z = make([]int, zlen, zcap)

copy(z, x) // a built-in function; see text

}

z[len(x)] = y

return z

}

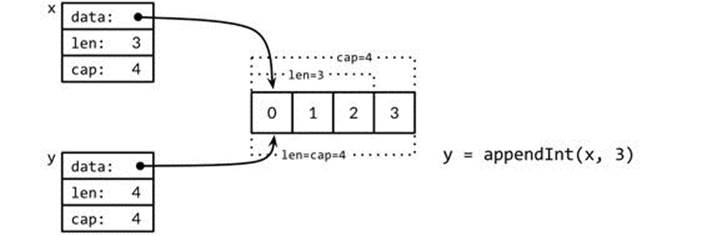

Each call to appendInt must check whether the slice has sufficient capacity to hold the new elements in the existing array. If so, it extends the slice by defining a larger slice (still within the original array), copies the element y into the new space, and returns the slice. The input x and the result z share the same underlying array.

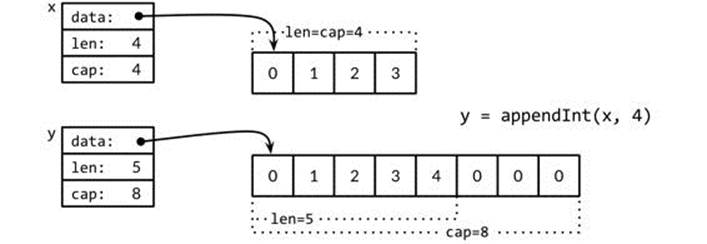

If there is insufficient space for growth, appendInt must allocate a new array big enough to hold the result, copy the values from x into it, then append the new element y. The result z now refers to a different underlying array than the array that x refers to.

It would be straightforward to copy the elements with explicit loops, but it’s easier to use the built-in function copy, which copies elements from one slice to another of the same type. Its first argument is the destination and its second is the source, resembling the order of operands in an assignment like dst = src. The slices may refer to the same underlying array; they may even overlap. Although we don’t use it here, copy returns the number of elements actually copied, which is the smaller of the two slice lengths, so there is no danger of running off the end or overwriting something out of range.

For efficiency, the new array is usually somewhat larger than the minimum needed to hold x and y. Expanding the array by doubling its size at each expansion avoids an excessive number of allocations and ensures that appending a single element takes constant time on average. This program demonstrates the effect:

func main() {

var x, y []int

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

y = appendInt(x, i)

fmt.Printf("%d cap=%d\t%v\n", i, cap(y), y)

x = y

}

}

Each change in capacity indicates an allocation and a copy:

0 cap=1 [0]

1 cap=2 [0 1]

2 cap=4 [0 1 2]

3 cap=4 [0 1 2 3]

4 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4]

5 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4 5]

6 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6]

7 cap=8 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7]

8 cap=16 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8]

9 cap=16 [0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9]

Let’s take a closer look at the i=3 iteration. The slice x contains the three elements [0 1 2] but has capacity 4, so there is a single element of slack at the end, and appendInt of the element 3 may proceed without reallocating. The resulting slice y has length and capacity 4, and has the same underlying array as the original slice x, as Figure 4.2 shows.

Figure 4.2. Appending with room to grow.

On the next iteration, i=4, there is no slack at all, so appendInt allocates a new array of size 8, copies the four elements [0 1 2 3] of x, and appends 4, the value of i. The resulting slice y has a length of 5 but a capacity of 8; the slack of 3 will save the next three iterations from the need to reallocate. The slices y and x are views of different arrays. This operation is depicted in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3. Appending without room to grow.

The built-in append function may use a more sophisticated growth strategy than appendInt’s simplistic one. Usually we don’t know whether a given call to append will cause a reallocation, so we can’t assume that the original slice refers to the same array as the resulting slice, nor that it refers to a different one. Similarly, we must not assume that assignments to elements of the old slice will (or will not) be reflected in the new slice. Consequently, it’s usual to assign the result of a call to append to the same slice variable whose value we passed to append:

runes = append(runes, r)

Updating the slice variable is required not just when calling append, but for any function that may change the length or capacity of a slice or make it refer to a different underlying array. To use slices correctly, it’s important to bear in mind that although the elements of the underlying array are indirect, the slice’s pointer, length, and capacity are not. To update them requires an assignment like the one above. In this respect, slices are not “pure” reference types but resemble an aggregate type such as this struct:

type IntSlice struct {

ptr *int

len, cap int

}

Our appendInt function adds a single element to a slice, but the built-in append lets us add more than one new element, or even a whole slice of them.

var x []int

x = append(x, 1)

x = append(x, 2, 3)

x = append(x, 4, 5, 6)

x = append(x, x...) // append the slice x

fmt.Println(x) // "[1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6]"

With the small modification shown below, we can match the behavior of the built-in append. The ellipsis “...” in the declaration of appendInt makes the function variadic: it accepts any number of final arguments. The corresponding ellipsis in the call above to append shows how to supply a list of arguments from a slice. We’ll explain this mechanism in detail in Section 5.7.

func appendInt(x []int, y ...int) []int {

var z []int

zlen := len(x) + len(y)

// ...expand z to at least zlen...

copy(z[len(x):], y)

return z

}

The logic to expand z’s underlying array remains unchanged and is not shown.

4.2.2 In-Place Slice Techniques

Let’s see more examples of functions that, like rotate and reverse, modify the elements of a slice in place. Given a list of strings, the nonempty function returns the non-empty ones:

gopl.io/ch4/nonempty

// Nonempty is an example of an in-place slice algorithm.

package main

import "fmt"

// nonempty returns a slice holding only the non-empty strings.

// The underlying array is modified during the call.

func nonempty(strings []string) []string {

i := 0

for _, s := range strings {

if s != "" {

strings[i] = s

i++

}

}

return strings[:i]

}

The subtle part is that the input slice and the output slice share the same underlying array. This avoids the need to allocate another array, though of course the contents of data are partly overwritten, as evidenced by the second print statement:

data := []string{"one", "", "three"}

fmt.Printf("%q\n", nonempty(data)) // `["one" "three"]`

fmt.Printf("%q\n", data) // `["one" "three" "three"]`

Thus we would usually write: data = nonempty(data).

The nonempty function can also be written using append:

func nonempty2(strings []string) []string {

out := strings[:0] // zero-length slice of original

for _, s := range strings {

if s != "" {

out = append(out, s)

}

}

return out

}

Whichever variant we use, reusing an array in this way requires that at most one output value is produced for each input value, which is true of many algorithms that filter out elements of a sequence or combine adjacent ones. Such intricate slice usage is the exception, not the rule, but it can be clear, efficient, and useful on occasion.

A slice can be used to implement a stack. Given an initially empty slice stack, we can push a new value onto the end of the slice with append:

stack = append(stack, v) // push v

The top of the stack is the last element:

top := stack[len(stack)-1] // top of stack

and shrinking the stack by popping that element is

stack = stack[:len(stack)-1] // pop

To remove an element from the middle of a slice, preserving the order of the remaining elements, use copy to slide the higher-numbered elements down by one to fill the gap:

func remove(slice []int, i int) []int {

copy(slice[i:], slice[i+1:])

return slice[:len(slice)-1]

}

func main() {

s := []int{5, 6, 7, 8, 9}

fmt.Println(remove(s, 2)) // "[5 6 8 9]"

}

And if we don’t need to preserve the order, we can just move the last element into the gap:

func remove(slice []int, i int) []int {

slice[i] = slice[len(slice)-1]

return slice[:len(slice)-1]

}

func main() {

s := []int{5, 6, 7, 8, 9}

fmt.Println(remove(s, 2)) // "[5 6 9 8]

}

Exercise 4.3: Rewrite reverse to use an array pointer instead of a slice.

Exercise 4.4: Write a version of rotate that operates in a single pass.

Exercise 4.5: Write an in-place function to eliminate adjacent duplicates in a []string slice.

Exercise 4.6: Write an in-place function that squashes each run of adjacent Unicode spaces (see unicode.IsSpace) in a UTF-8-encoded []byte slice into a single ASCII space.

Exercise 4.7: Modify reverse to reverse the characters of a []byte slice that represents a UTF-8-encoded string, in place. Can you do it without allocating new memory?

4.3 Maps

The hash table is one of the most ingenious and versatile of all data structures. It is an unordered collection of key/value pairs in which all the keys are distinct, and the value associated with a given key can be retrieved, updated, or removed using a constant number of key comparisons on the average, no matter how large the hash table.

In Go, a map is a reference to a hash table, and a map type is written map[K]V, where K and V are the types of its keys and values. All of the keys in a given map are of the same type, and all of the values are of the same type, but the keys need not be of the same type as the values. The key type K must be comparable using ==, so that the map can test whether a given key is equal to one already within it. Though floating-point numbers are comparable, it’s a bad idea to compare floats for equality and, as we mentioned in Chapter 3, especially bad if NaN is a possible value. There are no restrictions on the value type V.

The built-in function make can be used to create a map:

ages := make(map[string]int) // mapping from strings to ints

We can also use a map literal to create a new map populated with some initial key/value pairs:

ages := map[string]int{

"alice": 31,

"charlie": 34,

}

This is equivalent to

ages := make(map[string]int)

ages["alice"] = 31

ages["charlie"] = 34

so an alternative expression for a new empty map is map[string]int{}.

Map elements are accessed through the usual subscript notation:

ages["alice"] = 32

fmt.Println(ages["alice"]) // "32"

and removed with the built-in function delete:

delete(ages, "alice") // remove element ages["alice"]

All of these operations are safe even if the element isn’t in the map; a map lookup using a key that isn’t present returns the zero value for its type, so, for instance, the following works even when "bob" is not yet a key in the map because the value of ages["bob"] will be 0.

ages["bob"] = ages["bob"] + 1 // happy birthday!

The shorthand assignment forms x += y and x++ also work for map elements, so we can rewrite the statement above as

ages["bob"] += 1

or even more concisely as

ages["bob"]++

But a map element is not a variable, and we cannot take its address:

_ = &ages["bob"] // compile error: cannot take address of map element

One reason that we can’t take the address of a map element is that growing a map might cause rehashing of existing elements into new storage locations, thus potentially invalidating the address.

To enumerate all the key/value pairs in the map, we use a range-based for loop similar to those we saw for slices. Successive iterations of the loop cause the name and age variables to be set to the next key/value pair:

for name, age := range ages {

fmt.Printf("%s\t%d\n", name, age)

}

The order of map iteration is unspecified, and different implementations might use a different hash function, leading to a different ordering. In practice, the order is random, varying from one execution to the next. This is intentional; making the sequence vary helps force programs to be robust across implementations. To enumerate the key/value pairs in order, we must sort the keys explicitly, for instance, using the Strings function from the sort package if the keys are strings. This is a common pattern:

import "sort"

var names []string

for name := range ages {

names = append(names, name)

}

sort.Strings(names)

for _, name := range names {

fmt.Printf("%s\t%d\n", name, ages[name])

}

Since we know the final size of names from the outset, it is more efficient to allocate an array of the required size up front. The statement below creates a slice that is initially empty but has sufficient capacity to hold all the keys of the ages map:

names := make([]string, 0, len(ages))

In the first range loop above, we require only the keys of the ages map, so we omit the second loop variable. In the second loop, we require only the elements of the names slice, so we use the blank identifier _ to ignore the first variable, the index.

The zero value for a map type is nil, that is, a reference to no hash table at all.

var ages map[string]int

fmt.Println(ages == nil) // "true"

fmt.Println(len(ages) == 0) // "true"

Most operations on maps, including lookup, delete, len, and range loops, are safe to perform on a nil map reference, since it behaves like an empty map. But storing to a nil map causes a panic:

ages["carol"] = 21 // panic: assignment to entry in nil map

You must allocate the map before you can store into it.

Accessing a map element by subscripting always yields a value. If the key is present in the map, you get the corresponding value; if not, you get the zero value for the element type, as we saw with ages["bob"]. For many purposes that’s fine, but sometimes you need to know whether the element was really there or not. For example, if the element type is numeric, you might have to distinguish between a nonexistent element and an element that happens to have the value zero, using a test like this:

age, ok := ages["bob"]

if !ok { /* "bob" is not a key in this map; age == 0. */ }

You’ll often see these two statements combined, like this:

if age, ok := ages["bob"]; !ok { /* ... */ }

Subscripting a map in this context yields two values; the second is a boolean that reports whether the element was present. The boolean variable is often called ok, especially if it is immediately used in an if condition.

As with slices, maps cannot be compared to each other; the only legal comparison is with nil. To test whether two maps contain the same keys and the same associated values, we must write a loop:

func equal(x, y map[string]int) bool {

if len(x) != len(y) {

return false

}

for k, xv := range x {

if yv, ok := y[k]; !ok || yv != xv {

return false

}

}

return true

}

Observe how we use !ok to distinguish the “missing” and “present but zero” cases. Had we naïvely written xv != y[k], the call below would incorrectly report its arguments as equal:

// True if equal is written incorrectly.

equal(map[string]int{"A": 0}, map[string]int{"B": 42})

Go does not provide a set type, but since the keys of a map are distinct, a map can serve this purpose. To illustrate, the program dedup reads a sequence of lines and prints only the first occurrence of each distinct line. (It’s a variant of the dup program that we showed in Section 1.3.) Thededup program uses a map whose keys represent the set of lines that have already appeared to ensure that subsequent occurrences are not printed.

gopl.io/ch4/dedup

func main() {

seen := make(map[string]bool) // a set of strings

input := bufio.NewScanner(os.Stdin)

for input.Scan() {

line := input.Text()

if !seen[line] {

seen[line] = true

fmt.Println(line)

}

}

if err := input.Err(); err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "dedup: %v\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

}

Go programmers often describe a map used in this fashion as a “set of strings” without further ado, but beware, not all map[string]bool values are simple sets; some may contain both true and false values.

Sometimes we need a map or set whose keys are slices, but because a map’s keys must be comparable, this cannot be expressed directly. However, it can be done in two steps. First we define a helper function k that maps each key to a string, with the property that k(x) == k(y) if and only if we consider x and y equivalent. Then we create a map whose keys are strings, applying the helper function to each key before we access the map.

The example below uses a map to record the number of times Add has been called with a given list of strings. It uses fmt.Sprintf to convert a slice of strings into a single string that is a suitable map key, quoting each slice element with %q to record string boundaries faithfully:

var m = make(map[string]int)

func k(list []string) string { return fmt.Sprintf("%q", list) }

func Add(list []string) { m[k(list)]++ }

func Count(list []string) int { return m[k(list)] }

The same approach can be used for any non-comparable key type, not just slices. It’s even useful for comparable key types when you want a definition of equality other than ==, such as case-insensitive comparisons for strings. And the type of k(x) needn’t be a string; any comparable type with the desired equivalence property will do, such as integers, arrays, or structs.

Here’s another example of maps in action, a program that counts the occurrences of each distinct Unicode code point in its input. Since there are a large number of possible characters, only a small fraction of which would appear in any particular document, a map is a natural way to keep track of just the ones that have been seen and their corresponding counts.

gopl.io/ch4/charcount

// Charcount computes counts of Unicode characters.

package main

import (

"bufio"

"fmt"

"io"

"os"

"unicode"

"unicode/utf8"

)

func main() {

counts := make(map[rune]int) // counts of Unicode characters

var utflen [utf8.UTFMax + 1]int // count of lengths of UTF-8 encodings

invalid := 0 // count of invalid UTF-8 characters

in := bufio.NewReader(os.Stdin)

for {

r, n, err := in.ReadRune() // returns rune, nbytes, error

if err == io.EOF {

break

}

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "charcount: %v\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

if r == unicode.ReplacementChar && n == 1 {

invalid++

continue

}

counts[r]++

utflen[n]++

}

fmt.Printf("rune\tcount\n")

for c, n := range counts {

fmt.Printf("%q\t%d\n", c, n)

}

fmt.Print("\nlen\tcount\n")

for i, n := range utflen {

if i > 0 {

fmt.Printf("%d\t%d\n", i, n)

}

}

if invalid > 0 {

fmt.Printf("\n%d invalid UTF-8 characters\n", invalid)

}

}

The ReadRune method performs UTF-8 decoding and returns three values: the decoded rune, the length in bytes of its UTF-8 encoding, and an error value. The only error we expect is end-of-file. If the input was not a legal UTF-8 encoding of a rune, the returned rune isunicode.ReplacementChar and the length is 1.

The charcount program also prints a count of the lengths of the UTF-8 encodings of the runes that appeared in the input. A map is not the best data structure for that; since encoding lengths range only from 1 to utf8.UTFMax (which has the value 4), an array is more compact.

As an experiment, we ran charcount on this book itself at one point. Although it’s mostly in English, of course, it does have a fair number of non-ASCII characters. Here are the top ten:

° 27 ![]() 15

15 ![]() 14 é 13 x 10 ≤ 5 × 5

14 é 13 x 10 ≤ 5 × 5 ![]() 4

4 ![]() 4

4 ![]() 3

3

and here is the distribution of the lengths of all the UTF-8 encodings:

len count

1 765391

2 60

3 70

4 0

The value type of a map can itself be a composite type, such as a map or slice. In the following code, the key type of graph is string and the value type is map[string]bool, representing a set of strings. Conceptually, graph maps a string to a set of related strings, its successors in a directed graph.

gopl.io/ch4/graph

var graph = make(map[string]map[string]bool)

func addEdge(from, to string) {

edges := graph[from]

if edges == nil {

edges = make(map[string]bool)

graph[from] = edges

}

edges[to] = true

}

func hasEdge(from, to string) bool {

return graph[from][to]

}

The addEdge function shows the idiomatic way to populate a map lazily, that is, to initialize each value as its key appears for the first time. The hasEdge function shows how the zero value of a missing map entry is often put to work: even if neither from nor to is present,graph[from][to] will always give a meaningful result.

Exercise 4.8: Modify charcount to count letters, digits, and so on in their Unicode categories, using functions like unicode.IsLetter.

Exercise 4.9: Write a program wordfreq to report the frequency of each word in an input text file. Call input.Split(bufio.ScanWords) before the first call to Scan to break the input into words instead of lines.

4.4 Structs

A struct is an aggregate data type that groups together zero or more named values of arbitrary types as a single entity. Each value is called a field. The classic example of a struct from data processing is the employee record, whose fields are a unique ID, the employee’s name, address, date of birth, position, salary, manager, and the like. All of these fields are collected into a single entity that can be copied as a unit, passed to functions and returned by them, stored in arrays, and so on.

These two statements declare a struct type called Employee and a variable called dilbert that is an instance of an Employee:

type Employee struct {

ID int

Name string

Address string

DoB time.Time

Position string

Salary int

ManagerID int

}

var dilbert Employee

The individual fields of dilbert are accessed using dot notation like dilbert.Name and dilbert.DoB. Because dilbert is a variable, its fields are variables too, so we may assign to a field:

dilbert.Salary -= 5000 // demoted, for writing too few lines of code

or take its address and access it through a pointer:

position := &dilbert.Position

*position = "Senior " + *position // promoted, for outsourcing to Elbonia

The dot notation also works with a pointer to a struct:

var employeeOfTheMonth *Employee = &dilbert

employeeOfTheMonth.Position += " (proactive team player)"

The last statement is equivalent to

(*employeeOfTheMonth).Position += " (proactive team player)"

Given an employee’s unique ID, the function EmployeeByID returns a pointer to an Employee struct. We can use the dot notation to access its fields:

func EmployeeByID(id int) *Employee { /* ... */ }

fmt.Println(EmployeeByID(dilbert.ManagerID).Position) // "Pointy-haired boss"

id := dilbert.ID

EmployeeByID(id).Salary = 0 // fired for... no real reason

The last statement updates the Employee struct that is pointed to by the result of the call to EmployeeByID. If the result type of EmployeeByID were changed to Employee instead of *Employee, the assignment statement would not compile since its left-hand side would not identify a variable.

Fields are usually written one per line, with the field’s name preceding its type, but consecutive fields of the same type may be combined, as with Name and Address here:

type Employee struct {

ID int

Name, Address string

DoB time.Time

Position string

Salary int

ManagerID int

}

Field order is significant to type identity. Had we also combined the declaration of the Position field (also a string), or interchanged Name and Address, we would be defining a different struct type. Typically we only combine the declarations of related fields.

The name of a struct field is exported if it begins with a capital letter; this is Go’s main access control mechanism. A struct type may contain a mixture of exported and unexported fields.

Struct types tend to be verbose because they often involve a line for each field. Although we could write out the whole type each time it is needed, the repetition would get tiresome. Instead, struct types usually appear within the declaration of a named type like Employee.

A named struct type S can’t declare a field of the same type S: an aggregate value cannot contain itself. (An analogous restriction applies to arrays.) But S may declare a field of the pointer type *S, which lets us create recursive data structures like linked lists and trees. This is illustrated in the code below, which uses a binary tree to implement an insertion sort:

gopl.io/ch4/treesort

type tree struct {

value int

left, right *tree

}

// Sort sorts values in place.

func Sort(values []int) {

var root *tree

for _, v := range values {

root = add(root, v)

}

appendValues(values[:0], root)

}

// appendValues appends the elements of t to values in order

// and returns the resulting slice.

func appendValues(values []int, t *tree) []int {

if t != nil {

values = appendValues(values, t.left)

values = append(values, t.value)

values = appendValues(values, t.right)

}

return values

}

func add(t *tree, value int) *tree {

if t == nil {

// Equivalent to return &tree{value: value}.

t = new(tree)

t.value = value

return t

}

if value < t.value {

t.left = add(t.left, value)

} else {

t.right = add(t.right, value)

}

return t

}

The zero value for a struct is composed of the zero values of each of its fields. It is usually desirable that the zero value be a natural or sensible default. For example, in bytes.Buffer, the initial value of the struct is a ready-to-use empty buffer, and the zero value of sync.Mutex, which we’ll see in Chapter 9, is a ready-to-use unlocked mutex. Sometimes this sensible initial behavior happens for free, but sometimes the type designer has to work at it.

The struct type with no fields is called the empty struct, written struct{}. It has size zero and carries no information but may be useful nonetheless. Some Go programmers use it instead of bool as the value type of a map that represents a set, to emphasize that only the keys are significant, but the space saving is marginal and the syntax more cumbersome, so we generally avoid it.

seen := make(map[string]struct{}) // set of strings

// ...

if _, ok := seen[s]; !ok {

seen[s] = struct{}{}

// ...first time seeing s...

}

4.4.1 Struct Literals

A value of a struct type can be written using a struct literal that specifies values for its fields.

type Point struct{ X, Y int }

p := Point{1, 2}

There are two forms of struct literal. The first form, shown above, requires that a value be specified for every field, in the right order. It burdens the writer (and reader) with remembering exactly what the fields are, and it makes the code fragile should the set of fields later grow or be reordered. Accordingly, this form tends to be used only within the package that defines the struct type, or with smaller struct types for which there is an obvious field ordering convention, like image.Point{x, y} or color.RGBA{red, green, blue, alpha}.

More often, the second form is used, in which a struct value is initialized by listing some or all of the field names and their corresponding values, as in this statement from the Lissajous program of Section 1.4:

anim := gif.GIF{LoopCount: nframes}

If a field is omitted in this kind of literal, it is set to the zero value for its type. Because names are provided, the order of fields doesn’t matter.

The two forms cannot be mixed in the same literal. Nor can you use the (order-based) first form of literal to sneak around the rule that unexported identifiers may not be referred to from another package.

package p

type T struct{ a, b int } // a and b are not exported

package q

import "p"

var _ = p.T{a: 1, b: 2} // compile error: can't reference a, b

var _ = p.T{1, 2} // compile error: can't reference a, b

Although the last line above doesn’t mention the unexported field identifiers, it’s really using them implicitly, so it’s not allowed.

Struct values can be passed as arguments to functions and returned from them. For instance, this function scales a Point by a specified factor:

func Scale(p Point, factor int) Point {

return Point{p.X * factor, p.Y * factor}

}

fmt.Println(Scale(Point{1, 2}, 5)) // "{5 10}"

For efficiency, larger struct types are usually passed to or returned from functions indirectly using a pointer,

func Bonus(e *Employee, percent int) int {

return e.Salary * percent / 100

}

and this is required if the function must modify its argument, since in a call-by-value language like Go, the called function receives only a copy of an argument, not a reference to the original argument.

func AwardAnnualRaise(e *Employee) {

e.Salary = e.Salary * 105 / 100

}

Because structs are so commonly dealt with through pointers, it’s possible to use this shorthand notation to create and initialize a struct variable and obtain its address:

pp := &Point{1, 2}

It is exactly equivalent to

pp := new(Point)

*pp = Point{1, 2}

but &Point{1, 2} can be used directly within an expression, such as a function call.

4.4.2 Comparing Structs

If all the fields of a struct are comparable, the struct itself is comparable, so two expressions of that type may be compared using == or !=. The == operation compares the corresponding fields of the two structs in order, so the two printed expressions below are equivalent:

type Point struct{ X, Y int }

p := Point{1, 2}

q := Point{2, 1}

fmt.Println(p.X == q.X && p.Y == q.Y) // "false"

fmt.Println(p == q) // "false"

Comparable struct types, like other comparable types, may be used as the key type of a map.

type address struct {

hostname string

port int

}

hits := make(map[address]int)

hits[address{"golang.org", 443}]++

4.4.3 Struct Embedding and Anonymous Fields

In this section, we’ll see how Go’s unusual struct embedding mechanism lets us use one named struct type as an anonymous field of another struct type, providing a convenient syntactic shortcut so that a simple dot expression like x.f can stand for a chain of fields like x.d.e.f.

Consider a 2-D drawing program that provides a library of shapes, such as rectangles, ellipses, stars, and wheels. Here are two of the types it might define:

type Circle struct {

X, Y, Radius int

}

type Wheel struct {

X, Y, Radius, Spokes int

}

A Circle has fields for the X and Y coordinates of its center, and a Radius. A Wheel has all the features of a Circle, plus Spokes, the number of inscribed radial spokes. Let’s create a wheel:

var w Wheel

w.X = 8

w.Y = 8

w.Radius = 5

w.Spokes = 20

As the set of shapes grows, we’re bound to notice similarities and repetition among them, so it may be convenient to factor out their common parts:

type Point struct {

X, Y int

}

type Circle struct {

Center Point

Radius int

}

type Wheel struct {

Circle Circle

Spokes int

}

The application may be clearer for it, but this change makes accessing the fields of a Wheel more verbose:

var w Wheel

w.Circle.Center.X = 8

w.Circle.Center.Y = 8

w.Circle.Radius = 5

w.Spokes = 20

Go lets us declare a field with a type but no name; such fields are called anonymous fields. The type of the field must be a named type or a pointer to a named type. Below, Circle and Wheel have one anonymous field each. We say that a Point is embedded within Circle, and aCircle is embedded within Wheel.

type Circle struct {

Point

Radius int

}

type Wheel struct {

Circle

Spokes int

}

Thanks to embedding, we can refer to the names at the leaves of the implicit tree without giving the intervening names:

var w Wheel

w.X = 8 // equivalent to w.Circle.Point.X = 8

w.Y = 8 // equivalent to w.Circle.Point.Y = 8

w.Radius = 5 // equivalent to w.Circle.Radius = 5

w.Spokes = 20

The explicit forms shown in the comments above are still valid, however, showing that “anonymous field” is something of a misnomer. The fields Circle and Point do have names—that of the named type—but those names are optional in dot expressions. We may omit any or all of the anonymous fields when selecting their subfields.

Unfortunately, there’s no corresponding shorthand for the struct literal syntax, so neither of these will compile:

w = Wheel{8, 8, 5, 20} // compile error: unknown fields

w = Wheel{X: 8, Y: 8, Radius: 5, Spokes: 20} // compile error: unknown fields

The struct literal must follow the shape of the type declaration, so we must use one of the two forms below, which are equivalent to each other:

gopl.io/ch4/embed

w = Wheel{Circle{Point{8, 8}, 5}, 20}

w = Wheel{

Circle: Circle{

Point: Point{X: 8, Y: 8},

Radius: 5,

},

Spokes: 20, // NOTE: trailing comma necessary here (and at Radius)

}

fmt.Printf("%#v\n", w)

// Output:

// Wheel{Circle:Circle{Point:Point{X:8, Y:8}, Radius:5}, Spokes:20}

w.X = 42

fmt.Printf("%#v\n", w)

// Output:

// Wheel{Circle:Circle{Point:Point{X:42, Y:8}, Radius:5}, Spokes:20}

Notice how the # adverb causes Printf’s %v verb to display values in a form similar to Go syntax. For struct values, this form includes the name of each field.

Because “anonymous” fields do have implicit names, you can’t have two anonymous fields of the same type since their names would conflict. And because the name of the field is implicitly determined by its type, so too is the visibility of the field. In the examples above, the Point andCircle anonymous fields are exported. Had they been unexported (point and circle), we could still use the shorthand form

w.X = 8 // equivalent to w.circle.point.X = 8

but the explicit long form shown in the comment would be forbidden outside the declaring package because circle and point would be inaccessible.

What we’ve seen so far of struct embedding is just a sprinkling of syntactic sugar on the dot notation used to select struct fields. Later, we’ll see that anonymous fields need not be struct types; any named type or pointer to a named type will do. But why would you want to embed a type that has no subfields?

The answer has to do with methods. The shorthand notation used for selecting the fields of an embedded type works for selecting its methods as well. In effect, the outer struct type gains not just the fields of the embedded type but its methods too. This mechanism is the main way that complex object behaviors are composed from simpler ones. Composition is central to object-oriented programming in Go, and we’ll explore it further in Section 6.3.

4.5 JSON

JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) is a standard notation for sending and receiving structured information. JSON is not the only such notation. XML (§7.14), ASN.1, and Google’s Protocol Buffers serve similar purposes and each has its niche, but because of its simplicity, readability, and universal support, JSON is the most widely used.

Go has excellent support for encoding and decoding these formats, provided by the standard library packages encoding/json, encoding/xml, encoding/asn1, and so on, and these packages all have similar APIs. This section gives a brief overview of the most important parts of theencoding/json package.

JSON is an encoding of JavaScript values—strings, numbers, booleans, arrays, and objects—as Unicode text. It’s an efficient yet readable representation for the basic data types of Chapter 3 and the composite types of this chapter—arrays, slices, structs, and maps.

The basic JSON types are numbers (in decimal or scientific notation), booleans (true or false), and strings, which are sequences of Unicode code points enclosed in double quotes, with backslash escapes using a similar notation to Go, though JSON’s \Uhhhh numeric escapes denote UTF-16 codes, not runes.

These basic types may be combined recursively using JSON arrays and objects. A JSON array is an ordered sequence of values, written as a comma-separated list enclosed in square brackets; JSON arrays are used to encode Go arrays and slices. A JSON object is a mapping from strings to values, written as a sequence of name:value pairs separated by commas and surrounded by braces; JSON objects are used to encode Go maps (with string keys) and structs. For example:

boolean true

number -273.15

string "She said \"Hello, ![]() \""

\""

array ["gold", "silver", "bronze"]

object {"year": 1980,

"event": "archery",

"medals": ["gold", "silver", "bronze"]}

Consider an application that gathers movie reviews and offers recommendations. Its Movie data type and a typical list of values are declared below. (The string literals after the Year and Color field declarations are field tags; we’ll explain them in a moment.)

gopl.io/ch4/movie

type Movie struct {

Title string

Year int `json:"released"`

Color bool `json:"color,omitempty"`

Actors []string

}

var movies = []Movie{

{Title: "Casablanca", Year: 1942, Color: false,

Actors: []string{"Humphrey Bogart", "Ingrid Bergman"}},

{Title: "Cool Hand Luke", Year: 1967, Color: true,

Actors: []string{"Paul Newman"}},

{Title: "Bullitt", Year: 1968, Color: true,

Actors: []string{"Steve McQueen", "Jacqueline Bisset"}},

// ...

}

Data structures like this are an excellent fit for JSON, and it’s easy to convert in both directions. Converting a Go data structure like movies to JSON is called marshaling. Marshaling is done by json.Marshal:

data, err := json.Marshal(movies)

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("JSON marshaling failed: %s", err)

}

fmt.Printf("%s\n", data)

Marshal produces a byte slice containing a very long string with no extraneous white space; we’ve folded the lines so it fits:

[{"Title":"Casablanca","released":1942,"Actors":["Humphrey Bogart","Ingr

id Bergman"]},{"Title":"Cool Hand Luke","released":1967,"color":true,"Ac

tors":["Paul Newman"]},{"Title":"Bullitt","released":1968,"color":true,"

Actors":["Steve McQueen","Jacqueline Bisset"]}]

This compact representation contains all the information but it’s hard to read. For human consumption, a variant called json.MarshalIndent produces neatly indented output. Two additional arguments define a prefix for each line of output and a string for each level of indentation:

data, err := json.MarshalIndent(movies, "", " ")

if err != nil {

log.Fatalf("JSON marshaling failed: %s", err)

}

fmt.Printf("%s\n", data)

The code above prints

[

{

"Title": "Casablanca",

"released": 1942,

"Actors": [

"Humphrey Bogart",

"Ingrid Bergman"

]

},

{

"Title": "Cool Hand Luke",

"released": 1967,

"color": true,

"Actors": [

"Paul Newman"

]

},

{

"Title": "Bullitt",

"released": 1968,

"color": true,

"Actors": [

"Steve McQueen",

"Jacqueline Bisset"

]

}

]

Marshaling uses the Go struct field names as the field names for the JSON objects (through reflection, as we’ll see in Section 12.6). Only exported fields are marshaled, which is why we chose capitalized names for all the Go field names.

You may have noticed that the name of the Year field changed to released in the output, and Color changed to color. That’s because of the field tags. A field tag is a string of metadata associated at compile time with the field of a struct:

Year int `json:"released"`

Color bool `json:"color,omitempty"`

A field tag may be any literal string, but it is conventionally interpreted as a space-separated list of key:"value" pairs; since they contain double quotation marks, field tags are usually written with raw string literals. The json key controls the behavior of the encoding/json package, and other encoding/... packages follow this convention. The first part of the json field tag specifies an alternative JSON name for the Go field. Field tags are often used to specify an idiomatic JSON name like total_count for a Go field named TotalCount. The tag for Colorhas an additional option, omitempty, which indicates that no JSON output should be produced if the field has the zero value for its type (false, here) or is otherwise empty. Sure enough, the JSON output for Casablanca, a black-and-white movie, has no color field.

The inverse operation to marshaling, decoding JSON and populating a Go data structure, is called unmarshaling, and it is done by json.Unmarshal. The code below unmarshals the JSON movie data into a slice of structs whose only field is Title. By defining suitable Go data structures in this way, we can select which parts of the JSON input to decode and which to discard. When Unmarshal returns, it has filled in the slice with the Title information; other names in the JSON are ignored.

var titles []struct{ Title string }

if err := json.Unmarshal(data, &titles); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("JSON unmarshaling failed: %s", err)

}

fmt.Println(titles) // "[{Casablanca} {Cool Hand Luke} {Bullitt}]"

Many web services provide a JSON interface—make a request with HTTP and back comes the desired information in JSON format. To illustrate, let’s query the GitHub issue tracker using its web-service interface. First we’ll define the necessary types and constants:

gopl.io/ch4/github

// Package github provides a Go API for the GitHub issue tracker.

// See https://developer.github.com/v3/search/#search-issues.

package github

import "time"

const IssuesURL = "https://api.github.com/search/issues"

type IssuesSearchResult struct {

TotalCount int `json:"total_count"`

Items []*Issue

}

type Issue struct {

Number int

HTMLURL string `json:"html_url"`

Title string

State string

User *User

CreatedAt time.Time `json:"created_at"`

Body string // in Markdown format

}

type User struct {

Login string

HTMLURL string `json:"html_url"`

}

As before, the names of all the struct fields must be capitalized even if their JSON names are not. However, the matching process that associates JSON names with Go struct names during unmarshaling is case-insensitive, so it’s only necessary to use a field tag when there’s an underscore in the JSON name but not in the Go name. Again, we are being selective about which fields to decode; the GitHub search response contains considerably more information than we show here.

The SearchIssues function makes an HTTP request and decodes the result as JSON. Since the query terms presented by a user could contain characters like ? and & that have special meaning in a URL, we use url.QueryEscape to ensure that they are taken literally.

gopl.io/ch4/github

package github

import (

"encoding/json"

"fmt"

"net/http"

"net/url"

"strings"

)

// SearchIssues queries the GitHub issue tracker.

func SearchIssues(terms []string) (*IssuesSearchResult, error) {

q := url.QueryEscape(strings.Join(terms, " "))

resp, err := http.Get(IssuesURL + "?q=" + q)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

// We must close resp.Body on all execution paths.

// (Chapter 5 presents 'defer', which makes this simpler.)

if resp.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

resp.Body.Close()

return nil, fmt.Errorf("search query failed: %s", resp.Status)

}

var result IssuesSearchResult

if err := json.NewDecoder(resp.Body).Decode(&result); err != nil {

resp.Body.Close()

return nil, err

}

resp.Body.Close()

return &result, nil

}

The earlier examples used json.Unmarshal to decode the entire contents of a byte slice as a single JSON entity. For variety, this example uses the streaming decoder, json.Decoder, which allows several JSON entities to be decoded in sequence from the same stream, although we don’t need that feature here. As you might expect, there is a corresponding streaming encoder called json.Encoder.

The call to Decode populates the variable result. There are various ways we can format its value nicely. The simplest, demonstrated by the issues command below, is as a text table with fixed-width columns, but in the next section we’ll see a more sophisticated approach based on templates.

gopl.io/ch4/issues

// Issues prints a table of GitHub issues matching the search terms.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"os"

"gopl.io/ch4/github"

)

func main() {

result, err := github.SearchIssues(os.Args[1:])

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

fmt.Printf("%d issues:\n", result.TotalCount)

for _, item := range result.Items {

fmt.Printf("#%-5d %9.9s %.55s\n",

item.Number, item.User.Login, item.Title)

}

}

The command-line arguments specify the search terms. The command below queries the Go project’s issue tracker for the list of open bugs related to JSON decoding:

$ go build gopl.io/ch4/issues

$ ./issues repo:golang/go is:open json decoder

13 issues:

#5680 eaigner encoding/json: set key converter on en/decoder

#6050 gopherbot encoding/json: provide tokenizer

#8658 gopherbot encoding/json: use bufio

#8462 kortschak encoding/json: UnmarshalText confuses json.Unmarshal

#5901 rsc encoding/json: allow override type marshaling

#9812 klauspost encoding/json: string tag not symmetric

#7872 extempora encoding/json: Encoder internally buffers full output

#9650 cespare encoding/json: Decoding gives errPhase when unmarshalin

#6716 gopherbot encoding/json: include field name in unmarshal error me

#6901 lukescott encoding/json, encoding/xml: option to treat unknown fi

#6384 joeshaw encoding/json: encode precise floating point integers u

#6647 btracey x/tools/cmd/godoc: display type kind of each named type

#4237 gjemiller encoding/base64: URLEncoding padding is optional

The GitHub web-service interface at https://developer.github.com/v3/ has many more features than we have space for here.

Exercise 4.10: Modify issues to report the results in age categories, say less than a month old, less than a year old, and more than a year old.

Exercise 4.11: Build a tool that lets users create, read, update, and delete GitHub issues from the command line, invoking their preferred text editor when substantial text input is required.

Exercise 4.12: The popular web comic xkcd has a JSON interface. For example, a request to https://xkcd.com/571/info.0.json produces a detailed description of comic 571, one of many favorites. Download each URL (once!) and build an offline index. Write a tool xkcd that, using this index, prints the URL and transcript of each comic that matches a search term provided on the command line.

Exercise 4.13: The JSON-based web service of the Open Movie Database lets you search https://omdbapi.com/ for a movie by name and download its poster image. Write a tool poster that downloads the poster image for the movie named on the command line.

4.6 Text and HTML Templates

The previous example does only the simplest possible formatting, for which Printf is entirely adequate. But sometimes formatting must be more elaborate, and it’s desirable to separate the format from the code more completely. This can be done with the text/template andhtml/template packages, which provide a mechanism for substituting the values of variables into a text or HTML template.

A template is a string or file containing one or more portions enclosed in double braces, {{...}}, called actions. Most of the string is printed literally, but the actions trigger other behaviors. Each action contains an expression in the template language, a simple but powerful notation for printing values, selecting struct fields, calling functions and methods, expressing control flow such as if-else statements and range loops, and instantiating other templates. A simple template string is shown below:

gopl.io/ch4/issuesreport

const templ = `{{.TotalCount}} issues:

{{range .Items}}----------------------------------------

Number: {{.Number}}

User: {{.User.Login}}

Title: {{.Title | printf "%.64s"}}

Age: {{.CreatedAt | daysAgo}} days

{{end}}`

This template first prints the number of matching issues, then prints the number, user, title, and age in days of each one. Within an action, there is a notion of the current value, referred to as “dot” and written as “.”, a period. The dot initially refers to the template’s parameter, which will be agithub.IssuesSearchResult in this example. The {{.TotalCount}} action expands to the value of the TotalCount field, printed in the usual way. The {{range .Items}} and {{end}} actions create a loop, so the text between them is expanded multiple times, with dot bound to successive elements of Items.

Within an action, the | notation makes the result of one operation the argument of another, analogous to a Unix shell pipeline. In the case of Title, the second operation is the printf function, which is a built-in synonym for fmt.Sprintf in all templates. For Age, the second operation is the following function, daysAgo, which converts the CreatedAt field into an elapsed time, using time.Since:

func daysAgo(t time.Time) int {

return int(time.Since(t).Hours() / 24)

}

Notice that the type of CreatedAt is time.Time, not string. In the same way that a type may control its string formatting (§2.5) by defining certain methods, a type may also define methods to control its JSON marshaling and unmarshaling behavior. The JSON-marshaled value of atime.Time is a string in a standard format.

Producing output with a template is a two-step process. First we must parse the template into a suitable internal representation, and then execute it on specific inputs. Parsing need be done only once. The code below creates and parses the template templ defined above. Note the chaining of method calls: template.New creates and returns a template; Funcs adds daysAgo to the set of functions accessible within this template, then returns that template; finally, Parse is called on the result.

report, err := template.New("report").

Funcs(template.FuncMap{"daysAgo": daysAgo}).

Parse(templ)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

Because templates are usually fixed at compile time, failure to parse a template indicates a fatal bug in the program. The template.Must helper function makes error handling more convenient: it accepts a template and an error, checks that the error is nil (and panics otherwise), and then returns the template. We’ll come back to this idea in Section 5.9.

Once the template has been created, augmented with daysAgo, parsed, and checked, we can execute it using a github.IssuesSearchResult as the data source and os.Stdout as the destination:

var report = template.Must(template.New("issuelist").

Funcs(template.FuncMap{"daysAgo": daysAgo}).

Parse(templ))

func main() {

result, err := github.SearchIssues(os.Args[1:])

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

if err := report.Execute(os.Stdout, result); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

The program prints a plain text report like this:

$ go build gopl.io/ch4/issuesreport

$ ./issuesreport repo:golang/go is:open json decoder

13 issues:

----------------------------------------

Number: 5680

User: eaigner

Title: encoding/json: set key converter on en/decoder

Age: 750 days

----------------------------------------

Number: 6050

User: gopherbot

Title: encoding/json: provide tokenizer

Age: 695 days

----------------------------------------

...

Now let’s turn to the html/template package. It uses the same API and expression language as text/template but adds features for automatic and context-appropriate escaping of strings appearing within HTML, JavaScript, CSS, or URLs. These features can help avoid a perennial security problem of HTML generation, an injection attack, in which an adversary crafts a string value like the title of an issue to include malicious code that, when improperly escaped by a template, gives them control over the page.

The template below prints the list of issues as an HTML table. Note the different import:

gopl.io/ch4/issueshtml

import "html/template"

var issueList = template.Must(template.New("issuelist").Parse(`

<h1>{{.TotalCount}} issues</h1>

<table>

<tr style='text-align: left'>

<th>#</th>

<th>State</th>

<th>User</th>

<th>Title</th>

</tr>

{{range .Items}}

<tr>

<td><a href='{{.HTMLURL}}'>{{.Number}}</td>

<td>{{.State}}</td>

<td><a href='{{.User.HTMLURL}}'>{{.User.Login}}</a></td>

<td><a href='{{.HTMLURL}}'>{{.Title}}</a></td>

</tr>

{{end}}

</table>

`))

The command below executes the new template on the results of a slightly different query:

$ go build gopl.io/ch4/issueshtml

$ ./issueshtml repo:golang/go commenter:gopherbot json encoder >issues.html

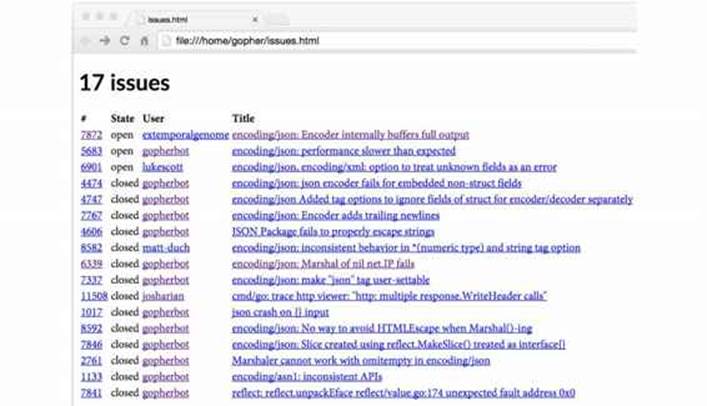

Figure 4.4 shows the appearance of the table in a web browser. The links connect to the appropriate web pages at GitHub.

Figure 4.4. An HTML table of Go project issues relating to JSON encoding.

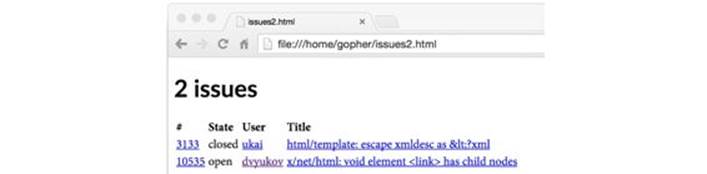

None of the issues in Figure 4.4 pose a challenge for HTML, but we can see the effect more clearly with issues whose titles contain HTML metacharacters like & and <. We’ve selected two such issues for this example:

$ ./issueshtml repo:golang/go 3133 10535 >issues2.html

Figure 4.5 shows the result of this query. Notice that the html/template package automatically HTML-escaped the titles so that they appear literally. Had we used the text/template package by mistake, the four-character string "<" would have been rendered as a less-than character'<', and the string "<link>" would have become a link element, changing the structure of the HTML document and perhaps compromising its security.

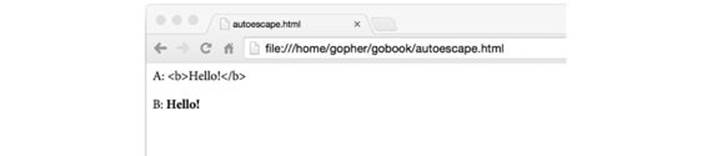

We can suppress this auto-escaping behavior for fields that contain trusted HTML data by using the named string type template.HTML instead of string. Similar named types exist for trusted JavaScript, CSS, and URLs. The program below demonstrates the principle by using two fields with the same value but different types: A is a string and B is a template.HTML.

Figure 4.5. HTML metacharacters in issue titles are correctly displayed.

gopl.io/ch4/autoescape

func main() {

const templ = `<p>A: {{.A}}</p><p>B: {{.B}}</p>`

t := template.Must(template.New("escape").Parse(templ))

var data struct {

A string // untrusted plain text

B template.HTML // trusted HTML

}

data.A = "<b>Hello!</b>"

data.B = "<b>Hello!</b>"

if err := t.Execute(os.Stdout, data); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}

Figure 4.6 shows the template’s output as it appears in a browser. We can see that A was subject to escaping but B was not.

Figure 4.6. String values are HTML-escaped but template.HTML values are not.

We have space here to show only the most basic features of the template system. As always, for more information, consult the package documentation:

$ go doc text/template

$ go doc html/template

Exercise 4.14: Create a web server that queries GitHub once and then allows navigation of the list of bug reports, milestones, and users.