Functional Programming in Scala (2015)

Part 1. Introduction to functional programming

Chapter 2. Getting started with functional programming in Scala

Now that we have committed to using only pure functions, a question naturally emerges: how do we write even the simplest of programs? Most of us are used to thinking of programs as sequences of instructions that are executed in order, where each instruction has some kind of effect. In this chapter, we’ll begin learning how to write programs in the Scala language just by combining pure functions.

This chapter is mainly intended for those readers who are new to Scala, to functional programming, or both. Immersion is an effective method for learning a foreign language, so we’ll just dive in. The only way for Scala code to look familiar and not foreign is if we look at a lot of Scala code. We’ve already seen some in the first chapter. In this chapter, we’ll start by looking at a small but complete program. We’ll then break it down piece by piece to examine what it does in some detail, in order to understand the basics of the Scala language and its syntax. Our goal in this book is to teach functional programming, but we’ll use Scala as our vehicle, and need to know enough of the Scala language and its syntax to get going.

Once we’ve covered some of the basic elements of the Scala language, we’ll then introduce some of the basic techniques for how to write functional programs. We’ll discuss how to write loops using tail recursive functions, and we’ll introduce higher-order functions (HOFs). HOFs are functions that take other functions as arguments and may themselves return functions as their output. We’ll also look at some examples of polymorphic HOFs where we use types to guide us toward an implementation.

There’s a lot of new material in this chapter. Some of the material related to HOFs may be brain-bending if you have a lot of experience programming in a language without the ability to pass functions around like that. Remember, it’s not crucial that you internalize every single concept in this chapter, or solve every exercise. We’ll come back to these concepts again from different angles throughout the book, and our goal here is just to give you some initial exposure.

2.1. Introducing Scala the language: an example

The following is a complete program listing in Scala, which we’ll talk through. We aren’t introducing any new concepts of functional programming here. Our goal is just to introduce the Scala language and its syntax.

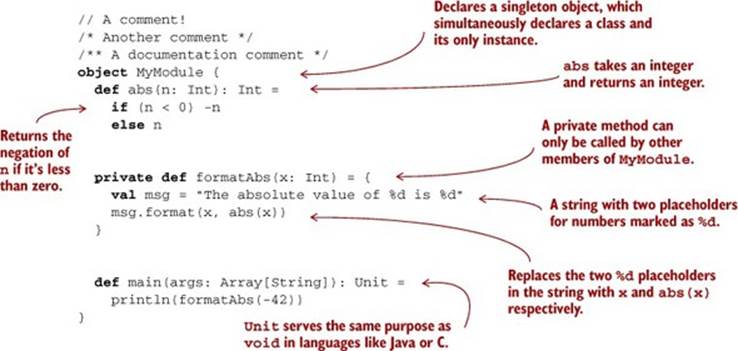

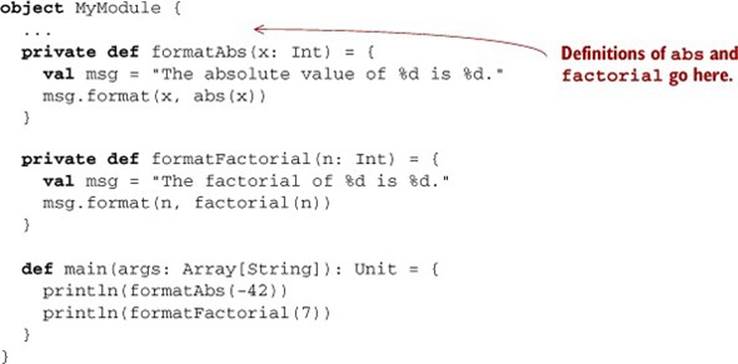

Listing 2.1. A simple Scala program

We declare an object (also known as a module) named MyModule. This is simply to give our code a place to live and a name so we can refer to it later. Scala code has to be in an object or a class, and we use an object here because it’s simpler. We put our code inside the object, between curly braces. We’ll discuss objects and classes in more detail shortly. For now, we’ll just look at this particular object.

The MyModule object has three methods, introduced with the def keyword: abs, formatAbs, and main. We’ll use the term method to refer to some function or field defined within an object or class using the def keyword. Let’s now go through the methods of MyModule one by one.

The object keyword

The object keyword creates a new singleton type, which is like a class that only has a single named instance. If you’re familiar with Java, declaring an object in Scala is a lot like creating a new instance of an anonymous class.

Scala has no equivalent to Java’s static keyword, and an object is often used in Scala where you might use a class with static members in Java.

The abs method is a pure function that takes an integer and returns its absolute value:

def abs(n: Int): Int =

if (n < 0) -n

else n

The def keyword is followed by the name of the method, which is followed by the parameter list in parentheses. In this case, abs takes only one argument, n of type Int. Following the closing parenthesis of the argument list, an optional type annotation (the : Int) indicates that the type of the result is Int (the colon is pronounced “has type”).

The body of the method itself comes after a single equals sign (=). We’ll sometimes refer to the part of a declaration that goes before the equals sign as the left-hand side or signature, and the code that comes after the equals sign as the right-hand side or definition. Note the absence of an explicit return keyword. The value returned from a method is simply whatever value results from evaluating the right-hand side. All expressions, including if expressions, produce a result. Here, the right-hand side is a single expression whose value is either -n or n, depending on whethern < 0.

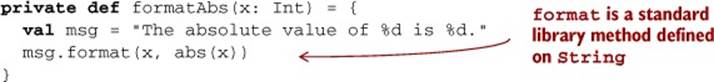

The formatAbs method is another pure function:

Here we’re calling the format method on the msg object, passing in the value of x along with the value of abs applied to x. This results in a new string with the occurrences of %d in msg replaced with the evaluated results of x and abs(x), respectively.

This method is declared private, which means that it can’t be called from any code outside of the MyModule object. This function takes an Int and returns a String, but note that the return type is not declared. Scala is usually able to infer the return types of methods, so they can be omitted, but it’s generally considered good style to explicitly declare the return types of methods that you expect others to use. This method is private to our module, so we can omit the type annotation.

The body of the method contains more than one statement, so we put them inside curly braces. A pair of braces containing statements is called a block. Statements are separated by newlines or by semicolons. In this case, we’re using a newline to separate our statements, so a semicolon isn’t necessary.

The first statement in the block declares a String named msg using the val keyword. It’s simply there to give a name to the string value so we can refer to it again. A val is an immutable variable, so inside the body of the formatAbs method the name msg will always refer to the sameString value. The Scala compiler will complain if you try to reassign msg to a different value in the same block.

Remember, a method simply returns the value of its right-hand side, so we don’t need a return keyword. In this case, the right-hand side is a block. In Scala, the value of a multistatement block inside curly braces is the same as the value returned by the last expression in the block. Therefore, the result of the formatAbs method is just the value returned by the call to msg.format(x, abs(x)).

Finally, our main method is an outer shell that calls into our purely functional core and prints the answer to the console. We’ll sometimes call such methods procedures (or impure functions) rather than functions, to emphasize the fact that they have side effects:

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit =

println(formatAbs(-42))

The name main is special because when you run a program, Scala will look for a method named main with a specific signature. It has to take an Array of Strings as its argument, and its return type must be Unit.

The args array will contain the arguments that were given at the command line that ran the program. We’re not using them here.

Unit serves a similar purpose to void in programming languages like C and Java. In Scala, every method has to return some value as long as it doesn’t crash or hang. But main doesn’t return anything meaningful, so there’s a special type Unit that is the return type of such methods. There’s only one value of this type and the literal syntax for it is (), a pair of empty parentheses, pronounced “unit” just like the type. Usually a return type of Unit is a hint that the method has a side effect.

The body of our main method prints to the console the String returned by the call to formatAbs. Note that the return type of println is Unit, which happens to be what we need to return from main.

2.2. Running our program

This section discusses the simplest possible way of running your Scala programs, suitable for short examples. More typically, you’ll build and run your Scala code using sbt, the build tool for Scala, and/or an IDE like IntelliJ or Eclipse. See the book’s source code repo on GitHub (https://github.com/fpinscala/fpinscala) for more information on getting set up with sbt.

The simplest way we can run this Scala program (MyModule) is from the command line, by invoking the Scala compiler directly ourselves. We start by putting the code in a file called MyModule.scala or something similar. We can then compile it to Java bytecode using the scalaccompiler:

> scalac MyModule.scala

This will generate some files ending with the .class suffix. These files contain compiled code that can be run with the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). The code can be executed using the scala command-line tool:

> scala MyModule

The absolute value of -42 is 42.

Actually, it’s not strictly necessary to compile the code first with scalac. A simple program like the one we’ve written here can be run using just the Scala interpreter by passing it to the scala command-line tool directly:

> scala MyModule.scala

The absolute value of -42 is 42.

This can be handy when using Scala for scripting. The interpreter will look for any object within the file MyModule.scala that has a main method with the appropriate signature, and will then call it.

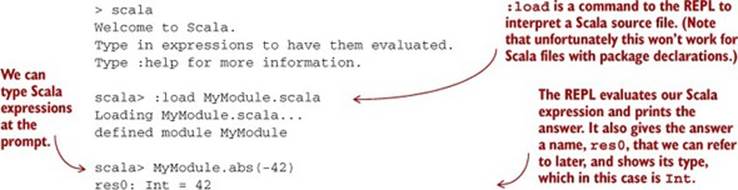

Lastly, an alternative way is to start the Scala interpreter’s interactive mode, the REPL (which stands for read-evaluate-print loop). It’s a great idea to have a REPL window open so you can try things out while you’re programming in Scala.

We can load our source file into the REPL and try things out (your actual console output may differ slightly):

It’s also possible to copy and paste individual lines of code into the REPL. It even has a paste mode (accessed with the :paste command) designed to paste code that spans multiple lines. It’s a good idea to get familiar with the REPL and its features because it’s a tool that you’ll use a lot as a Scala programmer.

2.3. Modules, objects, and namespaces

In this section, we’ll discuss some additional aspects of Scala’s syntax related to modules, objects, and namespaces. In the preceding REPL session, note that in order to refer to our abs method, we had to say MyModule.abs because abs was defined in the MyModule object. We say thatMyModule is its namespace. Aside from some technicalities, every value in Scala is what’s called an object,[1] and each object may have zero or more members. An object whose primary purpose is giving its members a namespace is sometimes called a module. A member can be a method declared with the def keyword, or it can be another object declared with val or object. Objects can also have other kinds of members that we’ll ignore for now.

1 Unlike Java, values of primitive types like Int are also considered objects for the purposes of this discussion.

We access the members of objects with the typical object-oriented dot notation, which is a namespace (the name that refers to the object) followed by a dot (the period character), followed by the name of the member, as in MyModule.abs(-42). To use the toString member on the object42, we’d use 42.toString. The implementations of members within an object can refer to each other unqualified (without prefixing the object name), but if needed they have access to their enclosing object using a special name: this.[2]

2 Note that in this book, we’ll use the term function to refer more generally to either so-called standalone functions like sqrt or abs, or members of some class, including methods. When it’s clear from the context, we’ll also use the terms method and function interchangeably, since what matters is not the syntax of invocation (obj.method(12) vs. method(obj, 12), but the fact that we’re talking about some parameterized block of code.

Note that even an expression like 2 + 1 is just calling a member of an object. In that case, what we’re calling is the + member of the object 2. It’s really syntactic sugar for the expression 2.+(1), which passes 1 as an argument to the method + on the object 2. Scala has no special notion ofoperators. It’s simply the case that + is a valid method name in Scala. Any method name can be used infix like that (omitting the dot and parentheses) when calling it with a single argument. For example, instead of MyModule.abs(42) we can say MyModule abs 42 and get the same result. You can use whichever you find more pleasing in any given case.

We can bring an object’s member into scope by importing it, which allows us to call it unqualified from then on:

scala> import MyModule.abs

import MyModule.abs

scala> abs(-42)

res0: 42

We can bring all of an object’s (nonprivate) members into scope by using the underscore syntax:

import MyModule._

2.4. Higher-order functions: passing functions to functions

Now that we’ve covered the basics of Scala’s syntax, we’ll move on to covering some of the basics of writing functional programs. The first new idea is this: functions are values. And just like values of other types—such as integers, strings, and lists—functions can be assigned to variables, stored in data structures, and passed as arguments to functions.

When writing purely functional programs, we’ll often find it useful to write a function that accepts other functions as arguments. This is called a higher-order function (HOF), and we’ll look next at some simple examples to illustrate. In later chapters, we’ll see how useful this capability really is, and how it permeates the functional programming style. But to start, suppose we wanted to adapt our program to print out both the absolute value of a number and the factorial of another number. Here’s a sample run of such a program:

The absolute value of -42 is 42

The factorial of 7 is 5040

2.4.1. A short detour: writing loops functionally

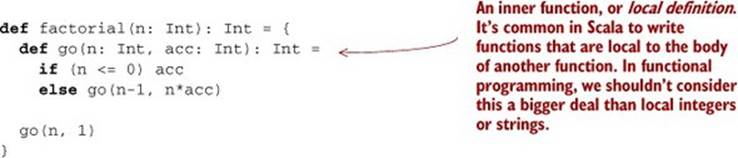

First, let’s write factorial:

The way we write loops functionally, without mutating a loop variable, is with a recursive function. Here we’re defining a recursive helper function inside the body of the factorial function. Such a helper function is often called go or loop by convention. In Scala, we can define functions inside any block, including within another function definition. Since it’s local, the go function can only be referred to from within the body of the factorial function, just like a local variable would. The definition of factorial finally just consists of a call to go with the initial conditions for the loop.

The arguments to go are the state for the loop. In this case, they’re the remaining value n, and the current accumulated factorial acc. To advance to the next iteration, we simply call go recursively with the new loop state (here, go(n-1, n*acc)), and to exit from the loop, we return a value without a recursive call (here, we return acc in the case that n <= 0). Scala detects this sort of self-recursion and compiles it to the same sort of bytecode as would be emitted for a while loop,[3] so long as the recursive call is in tail position. See the sidebar for the technical details on this, but the basic idea is that this optimization[4] (called tail call elimination) is applied when there’s no additional work left to do after the recursive call returns.

3 We can write while loops by hand in Scala, but it’s rarely necessary and considered bad form since it hinders good compositional style.

4 The term optimization is not really appropriate here. An optimization usually connotes some nonessential performance improvement, but when we use tail calls to write loops, we generally rely on their being compiled as iterative loops that don’t consume a call stack frame for each iteration (which would result in a StackOverflowError for large inputs).

Tail calls in Scala

A call is said to be in tail position if the caller does nothing other than return the value of the recursive call. For example, the recursive call to go(n-1,n*acc) we discussed earlier is in tail position, since the method returns the value of this recursive call directly and does nothing else with it. On the other hand, if we said 1 + go(n-1,n*acc), go would no longer be in tail position, since the method would still have work to do when go returned its result (namely, adding 1 to it).

If all recursive calls made by a function are in tail position, Scala automatically compiles the recursion to iterative loops that don’t consume call stack frames for each iteration. By default, Scala doesn’t tell us if tail call elimination was successful, but if we’re expecting this to occur for a recursive function we write, we can tell the Scala compiler about this assumption using the tailrec annotation (http://mng.bz/bWT5), so it can give us a compile error if it’s unable to eliminate the tail calls of the function. Here’s the syntax for this:

def factorial(n: Int): Int = {

@annotation.tailrec

def go(n: Int, acc: Int): Int =

if (n <= 0) acc

else go(n-1, n*acc)

go(n, 1)

}

We won’t talk much more about annotations in this book (you’ll find more information at http://mng.bz/GK8T), but we’ll use @annotation.tailrec extensively.

Note

See the preface for information on the exercises.

Exercise 2.1

![]()

Write a recursive function to get the nth Fibonacci number (http://mng.bz/C29s). The first two Fibonacci numbers are 0 and 1. The nth number is always the sum of the previous two—the sequence begins 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5. Your definition should use a local tail-recursive function.

def fib(n: Int): Int

2.4.2. Writing our first higher-order function

Now that we have factorial, let’s edit our program from before to include it.

Listing 2.2. A simple program including the factorial function

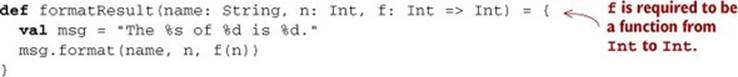

The two functions, formatAbs and formatFactorial, are almost identical. If we like, we can generalize these to a single function, formatResult, which accepts as an argument the function to apply to its argument:

Our formatResult function is a higher-order function (HOF) that takes another function, called f (see sidebar on variable-naming conventions). We give a type to f, as we would for any other parameter. Its type is Int => Int (pronounced “int to int” or “int arrow int”), which indicates that f expects an integer argument and will also return an integer.

Our function abs from before matches that type. It accepts an Int and returns an Int. And likewise, factorial accepts an Int and returns an Int, which also matches the Int => Int type. We can therefore pass abs or factorial as the f argument to formatResult:

scala> formatResult("absolute value", -42, abs)

res0: String = "The absolute value of -42 is 42."

scala> formatResult("factorial", 7, factorial)

res1: String = "The factorial of 7 is 5040."

Variable-naming conventions

It’s a common convention to use names like f, g, and h for parameters to a higher-order function. In functional programming, we tend to use very short variable names, even one-letter names. This is usually because HOFs are so general that they have no opinion on what the argument should actually do. All they know about the argument is its type. Many functional programmers feel that short names make code easier to read, since it makes the structure of the code easier to see at a glance.

2.5. Polymorphic functions: abstracting over types

So far we’ve defined only monomorphic functions, or functions that operate on only one type of data. For example, abs and factorial are specific to arguments of type Int, and the higher-order function formatResult is also fixed to operate on functions that take arguments of type Int. Often, and especially when writing HOFs, we want to write code that works for any type it’s given. These are called polymorphic functions,[5] and in the chapters ahead, you’ll get plenty of experience writing such functions. Here we’ll just introduce the idea.

5 We’re using the term polymorphism in a slightly different way than you might be used to if you’re familiar with object-oriented programming, where that term usually connotes some form of subtyping or inheritance relationship. There are no interfaces or subtyping here in this example. The kind of polymorphism we’re using here is sometimes called parametric polymorphism.

2.5.1. An example of a polymorphic function

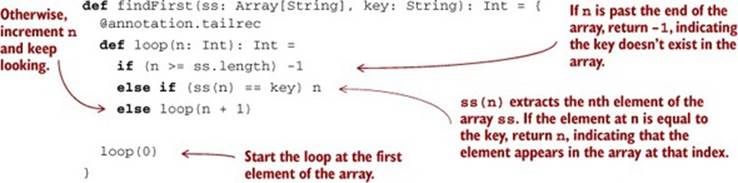

We can often discover polymorphic functions by observing that several monomorphic functions all share a similar structure. For example, the following monomorphic function, findFirst, returns the first index in an array where the key occurs, or -1 if it’s not found. It’s specialized for searching for a String in an Array of String values.

Listing 2.3. Monomorphic function to find a String in an array

The details of the code aren’t too important here. What’s important is that the code for findFirst will look almost identical if we’re searching for a String in an Array[String], an Int in an Array[Int], or an A in an Array[A] for any given type A. We can write findFirst more generally for any type A by accepting a function to use for testing a particular A value.

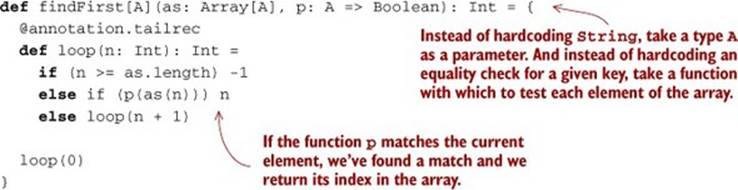

Listing 2.4. Polymorphic function to find an element in an array

This is an example of a polymorphic function, sometimes called a generic function. We’re abstracting over the type of the array and the function used for searching it. To write a polymorphic function as a method, we introduce a comma-separated list of type parameters, surrounded by square brackets (here, just a single [A]), following the name of the function, in this case findFirst. We can call the type parameters anything we want—[Foo, Bar, Baz] and [TheParameter, another_good_one] are valid type parameter declarations—though by convention we typically use short, one-letter, uppercase type parameter names like [A,B,C].

The type parameter list introduces type variables that can be referenced in the rest of the type signature (exactly analogous to how variables introduced in the parameter list to a function can be referenced in the body of the function). In findFirst, the type variable A is referenced in two places: the elements of the array are required to have the type A (since it’s an Array[A]), and the p function must accept a value of type A (since it’s a function of type A => Boolean). The fact that the same type variable is referenced in both places in the type signature implies that the type must be the same for both arguments, and the compiler will enforce this fact anywhere we try to call findFirst. If we try to search for a String in an Array[Int], for instance, we’ll get a type mismatch error.

Exercise 2.2

![]()

Implement isSorted, which checks whether an Array[A] is sorted according to a given comparison function:

def isSorted[A](as: Array[A], ordered: (A,A) => Boolean): Boolean

2.5.2. Calling HOFs with anonymous functions

When using HOFs, it’s often convenient to be able to call these functions with anonymous functions or function literals, rather than having to supply some existing named function. For instance, we can test the findFirst function in the REPL as follows:

scala> findFirst(Array(7, 9, 13), (x: Int) => x == 9)

res2: Int = 1

There is some new syntax here. The expression Array(7, 9, 13) is an array literal. It constructs a new array with three integers in it. Note the lack of a keyword like new to construct the array.

The syntax (x: Int) => x == 9 is a function literal or anonymous function. Instead of defining this function as a method with a name, we can define it inline using this convenient syntax. This particular function takes one argument called x of type Int, and it returns a Booleanindicating whether x is equal to 9.

In general, the arguments to the function are declared to the left of the => arrow, and we can then use them in the body of the function to the right of the arrow. For example, if we want to write an equality function that takes two integers and checks if they’re equal to each other, we could write that like this:

scala> (x: Int, y: Int) => x == y

res3: (Int, Int) => Boolean = <function2>

The <function2> notation given by the REPL indicates that the value of res3 is a function that takes two arguments. When the type of the function’s inputs can be inferred by Scala from the context, the type annotations on the function’s arguments may be elided, for example, (x,y) => x < y. We’ll see an example of this in the next section, and lots more examples throughout this book.

Functions as values in Scala

When we define a function literal, what is actually being defined in Scala is an object with a method called apply. Scala has a special rule for this method name, so that objects that have an apply method can be called as if they were themselves methods. When we define a function literal like (a, b) => a < b, this is really syntactic sugar for object creation:

val lessThan = new Function2[Int, Int, Boolean] {

def apply(a: Int, b: Int) = a < b

}

lessThan has type Function2[Int,Int,Boolean], which is usually written (Int,Int) => Boolean. Note that the Function2 interface (known in Scala as a trait) has an apply method. And when we call the lessThan function with less-Than(10, 20), it’s really syntactic sugar for calling its apply method:

scala> val b = lessThan.apply(10, 20)

b: Boolean = true

Function2 is just an ordinary trait (an interface) provided by the standard Scala library (API docs link: http://mng.bz/qFMr) to represent function objects that take two arguments. Also provided are Function1, Function3, and others, taking a number of arguments indicated by the name. Because functions are just ordinary Scala objects, we say that they’re first-class values. We’ll often use “function” to refer to either such a first-class function or a method, depending on context.

2.6. Following types to implementations

As you might have seen when writing isSorted, the universe of possible implementations is significantly reduced when implementing a polymorphic function. If a function is polymorphic in some type A, the only operations that can be performed on that A are those passed into the function as arguments (or that can be defined in terms of these given operations).[6] In some cases, you’ll find that the universe of possibilities for a given polymorphic type is constrained such that only one implementation is possible!

6 Technically, all values in Scala can be compared for equality (using ==), and turned into strings with toString and integers with hashCode. But this is something of a wart inherited from Java.

Let’s look at an example of a function signature that can only be implemented in one way. It’s a higher-order function for performing what’s called partial application. This function, partial1, takes a value and a function of two arguments, and returns a function of one argument as its result. The name comes from the fact that the function is being applied to some but not all of the arguments it requires:

def partial1[A,B,C](a: A, f: (A,B) => C): B => C

The partial1 function has three type parameters: A, B, and C. It then takes two arguments. The argument f is itself a function that takes two arguments of types A and B, respectively, and returns a value of type C. The value returned by partial1 will also be a function, of type B => C.

How would we go about implementing this higher-order function? It turns out that there’s only one implementation that compiles, and it follows logically from the type signature. It’s like a fun little logic puzzle.[7]

7 Even though it’s a fun puzzle, this isn’t a purely academic exercise. Functional programming in practice involves a lot of fitting building blocks together in the only way that makes sense. The purpose of this exercise is to get practice using higher-order functions, and using Scala’s type system to guide your programming.

Let’s start by looking at the type of thing that we have to return. The return type of partial1 is B => C, so we know that we have to return a function of that type. We can just begin writing a function literal that takes an argument of type B:

def partial1[A,B,C](a: A, f: (A,B) => C): B => C =

(b: B) => ???

This can be weird at first if you’re not used to writing anonymous functions. Where did that B come from? Well, we’ve just written, “Return a function that takes a value b of type B.” On the right-hand-side of the => arrow (where the question marks are now) comes the body of that anonymous function. We’re free to refer to the value b in there for the same reason that we’re allowed to refer to the value a in the body of partial1.[8]

8 Within the body of this inner function, the outer a is still in scope. We sometimes say that the inner function closes over its environment, which includes a.

Let’s keep going. Now that we’ve asked for a value of type B, what do we want to return from our anonymous function? The type signature says that it has to be a value of type C. And there’s only one way to get such a value. According to the signature, C is the return type of the function f. So the only way to get that C is to pass an A and a B to f. That’s easy:

def partial1[A,B,C](a: A, f: (A,B) => C): B => C =

(b: B) => f(a, b)

And we’re done! The result is a higher-order function that takes a function of two arguments and partially applies it. That is, if we have an A and a function that needs both A and B to produce C, we can get a function that just needs B to produce C (since we already have the A). It’s like saying, “If I can give you a carrot for an apple and a banana, and you already gave me an apple, you just have to give me a banana and I’ll give you a carrot.”

Note that the type annotation on b isn’t needed here. Since we told Scala the return type would be B => C, Scala knows the type of b from the context and we could just write b => f(a,b) as the implementation. Generally speaking, we’ll omit the type annotation on a function literal if it can be inferred by Scala.

Exercise 2.3

![]()

Let’s look at another example, currying,[9] which converts a function f of two arguments into a function of one argument that partially applies f. Here again there’s only one implementation that compiles. Write this implementation.

9 This is named after the mathematician Haskell Curry, who discovered the principle. It was independently discovered earlier by Moses Schoenfinkel, but Schoenfinkelization didn’t catch on.

def curry[A,B,C](f: (A, B) => C): A => (B => C)

Exercise 2.4

![]()

Implement uncurry, which reverses the transformation of curry. Note that since => associates to the right, A => (B => C) can be written as A => B => C.

def uncurry[A,B,C](f: A => B => C): (A, B) => C

Let’s look at a final example, function composition, which feeds the output of one function to the input of another function. Again, the implementation of this function is fully determined by its type signature.

Exercise 2.5

![]()

Implement the higher-order function that composes two functions.

def compose[A,B,C](f: B => C, g: A => B): A => C

This is such a common thing to want to do that Scala’s standard library provides compose as a method on Function1 (the interface for functions that take one argument). To compose two functions f and g, we simply say f compose g.[10] It also provides an andThen method. f andThen g is the same as g compose f:

10 Solving the compose exercise by using this library function is considered cheating.

scala> val f = (x: Double) => math.Pi / 2 - x

f: Double => Double = <function1>

scala> val cos = f andThen math.sin

cos: Double => Double = <function1>

It’s all well and good to puzzle together little one-liners like this, but what about programming with a large real-world code base? In functional programming, it turns out to be exactly the same. Higher-order functions like compose don’t care whether they’re operating on huge functions backed by millions of lines of code or functions that are simple one-liners. Polymorphic, higher-order functions often end up being extremely widely applicable, precisely because they say nothing about any particular domain and are simply abstracting over a common pattern that occurs in many contexts. For this reason, programming in the large has much the same flavor as programming in the small. We’ll write a lot of widely applicable functions over the course of this book, and the exercises in this chapter are a taste of the style of reasoning you’ll employ when writing such functions.

2.7. Summary

In this chapter, we learned enough of the Scala language to get going, and some preliminary functional programming concepts. We learned how to define simple functions and programs, including how we can express loops using recursion; then we introduced the idea of higher-order functions, and we got some practice writing polymorphic functions in Scala. We saw how the implementations of polymorphic functions are often significantly constrained, such that we can often simply “follow the types” to the correct implementation. This is something we’ll see a lot of in the chapters ahead.

Although we haven’t yet written any large or complex programs, the principles we’ve discussed here are scalable and apply equally well to programming in the large as they do to programming in the small.

Next we’ll look at using pure functions to manipulate data.