Hacking Happiness: Why Your Personal Data Counts and How Tracking It Can Change the World (2015)

[PART]

3

Be Proactive

18

BEYOND GDP

Too much and for too long, we seem to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things.1

ROBERT F. KENNEDY

LOOKING INWARD IS HARD.

Helping other people is hard.

That’s why we don’t do these things too often. We have the perfect excuse: We don’t have the time, because we need to earn more money. Yet there’s no set number for the perfect amount of money to earn, no set definition of well-being that comes from a certain amount of wealth. We’ve just been told it’s essential to build the economy by producing and consuming as much as possible.

Gross domestic product as a measurement is a useful tool; it’s a standardized way of looking at the world everyone has agreed on for more than a half century. Gross domestic product as a philosophy is killing us. A focus on quantity over quality means you aren’t ever asked to look inward, unless it’s to dig deeper to create more wealth. A focus on quantity over quality means you aren’t ever asked to help others, unless it provides a tax break or a reputation increase.

We have been forced to surrender our personal excellence. We don’t have time to fully reflect on how we could uniquely contribute value to the world. We have been forced to surrender community values. We don’t have time to help others if it will diminish our opportunities to produce more wealth.

Surrender. Yield. Consume for the sake of consuming. All you are worth is what you are worth.

No.

Screw you and the horse you rode in on. I’m done surrendering. It’s time to reimagine how the world sees wealth.

Beyond GDP is a movement that’s not actually based on measures of happiness. Well-being or metrics around quality of life are often involved, but Beyond GDP refers to work done in the past thirty years around the world by countries and organizations looking to find a new measure of economic wealth versus gross domestic product.

Robert Kennedy

In a famous speech delivered at the University of Kansas in 1968, Robert Kennedy outlined why gross domestic product was such a harmful measure of value. Credited as the beginning of the Beyond GDP movement, he outlined in his speech how the GDP prioritizes negative measures while ignoring other essential areas altogether:

Even if we act to erase material poverty, there is another greater task. It is to confront the poverty of satisfaction—purpose and dignity—that afflicts us all . . . Our gross national product, now, is over $800 billion dollars a year, but that gross national product—if we judge the United States of America by that—that Gross National Product counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for the people who break them. It counts the destruction of the redwood and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl . . . Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play . . . It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.

If this is true here at home, so it is true elsewhere in the world.2

Confronting the “poverty of satisfaction” is a difficult challenge. It means we’re forced to look beyond money to see what’s truly worth measuring in our lives. As Kennedy points out, the GDP credits things like “the destruction of the redwood.” While measuring the erosion of the environment is necessary, a dangerous precedent has been set with the creation of “offsets” regarding negative issues like pollution. Rather than work to eradicate the spread of dangerous environmental practices, countries are permitted to continue what they’re doing if incentivized to replace what they’ve destroyed. But these offsets are simply a delaying tactic for the inevitable when dealing with finite resources. It’s a justification of destructive and irreversible economic practices that embodies the poverty of satisfaction.

The landscape is changing, however. Sensor technologies and quantified self tools are helping people measure the quality of their health on a wide-scale basis. Positive psychology measures how our compassion can increase our happiness while putting others above our constant quest to consume. We are at a crossroads of time where we can measure the things that make life worthwhile if we supplant our reliance on money as a primary means of value.

Gross National Happiness

It was four years after Kennedy’s speech that Bhutan’s fourth Dragon King, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, coined the term Gross National Happiness (GNH). Spoken as a casual remark, Wangchuck felt the GDP did not serve as an accurate measure of value for his country based on Buddhist spiritual values. The term resonated with Wangchuck’s colleague, Karma Ura, who created the Centre for Bhutan Studies along with a survey tool that measured Bhutan’s well-being via a methodology quite different from the GDP.

While the name may imply a focus only on increase in mood, Gross National Happiness actually comprises measure of the four following pillars. And, as Wikipedia points out, “although the GNH framework reflects its Buddhist origins, it is solidly based upon the empirical research literature of happiness, positive psychology, and well-being.”3

· Promotion of sustainable development

· Preservation of cultural values

· Conservation of the natural environment

· Establishment of good governance

These pillars were later refined to include the following eight contributors to happiness:

· Physical, spiritual, and mental health

· Time-balance

· Social and community vitality

· Cultural vitality

· Education

· Living standards

· Good governance

· Ecological vitality

You’ll note that living standards are a contributor to happiness—money always plays a role in determining someone’s well-being, but isn’t the only contributor to happiness. The Bhutan model stresses that these contributing factors need to be in balance before a person can be in a place to pursue happiness.

If your time balance is out of whack and all you do is work, it won’t make a difference how much money you have regarding your well-being. If you are in good physical shape but don’t have access to educational resources, your happiness will also be affected. The number and types of indicators in GNH have been challenged since it first came into being. But the idea that they provide a better overall reflection of a country’s value than just monetary measures is a primary reason GNH has driven awareness for the Beyond GDP movement overall.

The What and the How

Three quick points about measuring well-being that are important to note while studying the evolution of the GDP Movement.

First is a concept known as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Proposed by psychologist Abraham Maslow in 1943 in his paper “A Theory of Human Motivation,”4 the concept posits that humans have basic needs they need met before they can focus on deeper levels of intrinsic fulfillment. This is why postulating on theories of happiness to a person without potable drinking water doesn’t make much sense. If someone is primarily focused on attaining basic needs to survive, achieving happiness for its own sake can be very difficult.

Second, it’s important to note how metrics like Gross National Happiness are measured. Along with census reports or other common public data, statisticians or social scientists utilize surveys to ask citizens to self-report their own levels of life satisfaction. Along with survey bias, the issue of participants answering questions based on knowing how their responses will be measured, surveys also are created with intent. This doesn’t infer they are nefarious in nature, only that how questions are posed and arranged in a survey can directly affect responses.

Finally, most of us tend to think that large-scale survey results are a form of quantified data when technically they’re actually the aggregation of multiple subjective answers. This is an important nuance to note: It means that policy or other decisions are being made on the collective and potentially biased responses of participants for any survey.

This is not to disparage data taken from surveys, but to note how the science of behavior will evolve in the near future. As mobile sensors become an accepted way to provide “answers” to surveys via passive data, the nature of subjectivity in responses will change. The Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kah-neman created a methodology called the Day Reconstruction Method5 as a measurement in social science where participants record their memories from the previous day in response to a survey or experiment. By definition people’s responses are subjective (their own truths) and also suffer from human error—we don’t always remember even recent facts about our lives with accuracy.

In a future incorporating mobile sensors, our activities will operate like our credit card bills: We’ll receive reports based on what we’ve actually done versus what we’ve remembered. For surveys based on happiness and well-being metrics, these reports may also take some getting used to.

For instance, my friend Neal Lathia, a senior research associate in the Networks and Operating Systems Group of Cambridge University’s Computer Laboratory, has created an app, called Emotion Sense, that collects data from all the passive sensors that a phone provides, including ambient noise. The app utilizes surveys about emotions and satisfaction with life that have been defined by psychologists to seek new insights previously unavailable, as mobile phones couldn’t collect this data before passive sensors existed. While a person may remember their previous day as being positive, Emotion Sense might have logged multiple times where a person’s voice registered frustration. While any app, like a survey, is influenced by the intention of the people who created it (and Neal has coauthored a paper on this issue, “Contextual Dissonance: Design Bias in Sensor-Based Experience Sampling Methods”),6 these types of sampling methods will be a complementary objective measure in the survey world. For example:

• If you’re asked to recall physical activity for a survey, you might only register your exercise, where a pedometer could measure actual steps you took, even if they were to and from your refrigerator. The accelerometer sensor in a smartphone can also tell the difference between motions related to sitting, standing, or active movement.

• You may rate a previous day as being negative largely based on the last thing that happened during the day. Daniel Kahneman, founder of behavioral economics, calls this phenomenon the riddle of experience versus memory, as our “experiencing selves” and our “remembering selves” perceive events in different ways.7 For instance, if you have a root canal for two hours and experience steady pain for the first ninety minutes but the last thirty is comfortable in comparison, Kahneman’s research shows many of us will report that session as not being painful. However, the reverse is also true: If the majority of the two hours is comfortable but you experience a great deal of pain in the final minutes of the session, you’ll recall the entire event as painful. These types of relationships will be revealed more often in the future as sensors become prevalent for data collection in surveys.

• We may soon get to the point where information from outside sources regarding a survey could come into play regarding data collection. In the same way three reporters can cover a story three different ways, other people’s responses to your actions may begin to factor into surveys you take. For instance, say you self-reported that a previous day had been fairly calm. If two other people using Google Glass devices recorded you at a Starbucks where you raised your voice at a barista, their impressions of your behavior might register differently than your own memory. Sensors measuring your behavior outside of the ones you’re wearing will likely come into play very soon for large-scale measurement of happiness and well-being.

Why Happiness?

Our politicians, media, and economic commentators dutifully continue to trumpet the GDP figures as information of great portent . . . There has been barely a stirring of curiosity regarding the premise that underlies its gross statistical summation. Whether from sincere conviction or from entrenched professional and financial interests, politicians, economists, and the rest have not been eager to see it changed. There is an urgent need for new indicators of progress, geared to the economy that actually exists.8

—CLIFFORD COBB, TED HALSTEAD, and JONATHAN ROWE

Jon Hall is the head of the National Human Development Reports Unit (HDRO), part of the United Nations Development Programme. Before joining the HDRO, Hall spent seven years working for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), where he led the Global Project on Measuring the Progress of Societies. He recently was lead author of Issues for a Global Human Development Agenda for HDRO and has been actively involved in research around human development and well-being since 2000. He is also advising the H(app)athon Project and provided me with a history of the Beyond GDP movement in an interview for Hacking H(app)iness. “Happiness is a single number that goes up and down and can easily be interpreted,” Hall noted in our interview, pointing out the power of a single and simple unifying metric to measure well-being. “That’s how I became converted about happiness as a single overarching metric of progress.”9

As a statistician, Hall became aware early in his work around well-being how important it was to create metrics that the average citizen could understand. As he noted in his interview for this book, after developing a groundbreaking report for the Australian Bureau of Statistics called Measuring Australia’s Progress, Hall showed the report to his mother for her thoughts. “She said, ‘I love the picture of my grandson on the cover, but it has too many numbers, so I gave it to your father.’”

It’s a fun story, but points out the disconnect Jon has been trying to eradicate for years: How can we make what we measure matter to the average citizen? One way is to keep things simple, which is why Jon favors the use of happiness metrics to measure life satisfaction.

Happiness provides a broad summary of how people feel about their lives. It doesn’t require statisticians or economists to add things up and take an average. Adding metrics together like health or education often gets people upset because the formulas complicate things: How does an extra year of life compare to an extra year of education, for example? There is no “right” answer. Happiness relies on people answering a simple question about how they feel.10

One of the more popular ways to measure life satisfaction or happiness is called the Cantril Ladder Scale (or self-anchoring striving scale), developed by Hadley Cantril in 1965 at Princeton University. People rate their lives based on an imaginary ladder where the steps are numbered zero to ten. Zero represents the worst possible life, and ten represents the best.

While people’s responses to these questions are inherently subjective, they do provide a way for people to simply express how they feel on a certain issue. As Hall points out, the more you collect these kinds of assessments, the more insights you also gain about a community, and the more the results can inspire conversations about things that matter.

One aggregate number changing around happiness is easy to collect and it can fluctuate for a multitude of reasons based on people’s concerns. The difference between socioeconomic groups can also be telling: If the measure goes up or down for a certain group, then that can trigger a conversation. Imagine if the government regularly reported measures of happiness, and imagine if happiness for white young women in Florida dropped last week, then that might trigger a broader debate in the media. Is it because of recent reports of rape? Is it because of reports that women in the state earn less than men? . . . And so on, and so on. The statistics can provide a window into a broader set of conversations that go beyond GDP: They can be very powerful ways to inspire much broader and informed debates around issues that are relevant to citizens.11

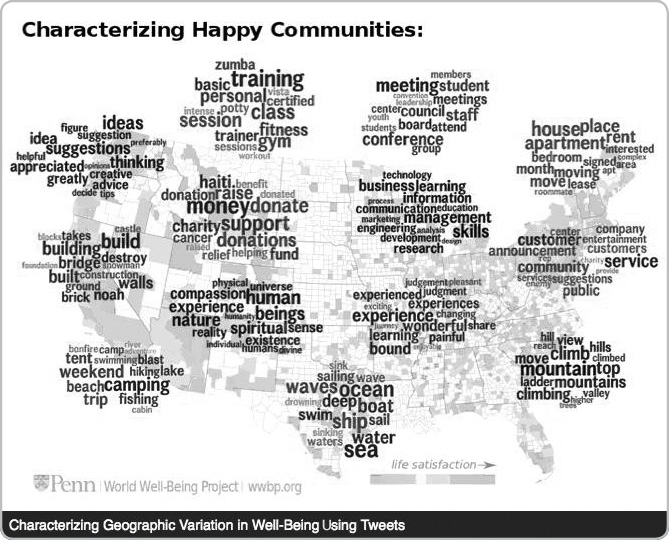

Social media is providing another platform for studying happiness and well-being that can help to soften our single-minded focus toward the GDP. The World Well-Being Project (WWBP), part of the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, is leveraging the massive availability of citizen commentary available through social media platforms to analyze psychosocial and physical well-being. By measuring language through sentiment analysis and other similar methodologies, the WWBP also gets to leverage the scale of social media to analyze large data sets for mining insights around happiness and well-being. The group’s vision is that their “insights and analyses can help policy makers to determine those policies that are not just in the best economic interest of the people, but those which indeed further people’s well-being.”12

One of WWBP’s studies, “Characterizing Geographic Variation in Well-Being Using Tweets,” showed that “language used in tweets from 1,300 different U.S. counties was found to be predictive of the subjective well-being of people living in those counties as measured by representative surveys.”13 A word cloud visualization of the report can be seen below. This practice of utilizing social media to study well-being sets a fascinating precedent, especially if results mirror surveys focused on the same issues. Citizens get to utilize transparent tools to broadcast their emotions, while organizations like the WWBP help analyze sentiment that could lead to policy change.

Evolution

From 2000 to the present, a number of initiatives and organizations have helped push the envelope to move Beyond GDP. One big push came from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In the early 2000s, the organization created a focus on measuring well-being for its thirty or so member states focused on global development. As Jon Hall noted in our interview, “The OECD getting involved in this work was a big stamp of approval; it gave the study of happiness and well-being a whole new level of seriousness.”14

The organization created an interactive Better Life Index, which lets users rate eleven topics in real time to see how OECD member countries compare based on each issue. The topics reflect what the OECD feels are essential to both material living conditions (housing, income, jobs) and quality of life (community, education, environment, governance, health, life satisfaction, safety, and work-life balance).

In 2007, the OECD held a world forum on Measuring and Fostering the Progress of Societies in Istanbul, and the EU organized a Beyond GDP conference, hosted by the European Commission, the European Parliament, the Club of Rome, the OECD, and the World Wildlife Fund, which met to discuss which indicators would be most appropriate to measure progress in the world. In 2008, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France created the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress focused on evolving the GDP. The commission was chaired by renowned economist Joseph Stiglitz.

After a number of other initiatives took place over the following years, in 2012 the United Nations implemented Resolution 65/309, a provision that permitted the Kingdom of Bhutan to convene a high-level meeting as part of the sixty-sixth session of the UN General Assembly in New York City. The Resolution recognized “that the gross domestic product . . . does not adequately reflect the happiness and well-being of people,” and “that the pursuit of happiness is a fundamental human goal.”15

On April 2, 2012, the prime minister of Bhutan convened the summit titled, “Wellbeing and Happiness: Defining a New Economic Paradigm.” The report from the meeting outlines a series of next steps attending organizations are taking to implement measures of well-being and happiness to move Beyond GDP. The prime minister of Bhutan, H.E. Mr. Jigmi Y. Thinley, opened the meeting with the following remarks:

We desperately need an economy that serves and nurtures the well-being of all sentient beings on earth and the human happiness that comes from living life in harmony with the natural world, with our communities, and with our inner selves. We need an economy that will serve humanity, not enslave it. It must prevent the imminent reversal of civilization and flourish within the natural bounds of our planet while ensuring the sustainable, equitable, and meaningful use of precious resources.16

The meeting was a watershed event in terms of the world formally looking to dismantle or at least complement the GDP with factors directly related to increasing measures of well-being, happiness, and flourishing that cannot be created or sustained by money alone.

Building Genuine Wealth

Mark Anielski is president and CEO of Anielski Management in Edmonton, Alberta, and author of the best-selling book The Economics of Happiness: Building Genuine Wealth. I interviewed Anielski about his ideas based on his experience in Canada with natural capital accounting and work developing alternative measures of economic progress beyond the GDP. One of the initial aspects of his book I found so compelling was in the introduction where he states, “Economics is more like a religion than either art or science.”17 I asked him to elaborate on this idea.

Economics is like a religion because it demands that society accept certain axioms, theories, principles, and suppositions about how human beings behave. Economics would have us believe that all people are consumers measured in terms of GDP, where everything is valued in terms of a money “price” that mediates all transactions and human relations. However, the idea that all people behave in a similar fashion in some hypothesized maximization of utility is a convenient simplification of how people actually behave. The trouble is, if you don’t believe in these theories, then you find yourself outside of the “religion” of neoclassical economics. But the truth is, people are not rational and do not behave the same. There is no such thing as a perfect market.18

It’s helpful to redefine economics as a study of people’s behavior versus simply the output of their labor. Well-being is multifaceted and relies on numerous cultural biases and predispositions that can’t be unilaterally measured by algorithms or indexes that don’t truly represent how people or communities work.

According to Anielski, Genuine Wealth must inherently factor in the human and environmental capital of a country or it won’t accurately measure what truly brings well-being to its citizens. And one of the reasons we’ve stayed with the GDP as a measure of value for so long is simply how hard it is to calculate these attributes as compared to utilizing fiscal metrics. But with Gross National Happiness and the Beyond GDP movement gaining traction, governments around the world are being pressured to use more transparent and accountable methods to measure what truly brings contentment in modern society. I asked Anielski about these ideas in relation to my thoughts on accountability-based influence and how our actions on individual and collective levels would begin to alter how the world views wealth moving forward:

I believe that genuine accountability will result when businesses and governments operate from the basis of a true balance sheet that keeps an account of the physical and qualitative conditions of its human (people), social (relationships), and natural capital assets. In the Genuine Wealth model I’ve developed, the measures of progress and proxies for the resilience or flourishing of assets will be tied to virtues, values, and principles for what people intuitively feel contributes most to their well-being. We will then be able to confidently say we are measuring what matters.19

The Present and the Future

Implementing changes based on happiness will take more time. But whereas many leading economists ten years ago discounted the study of well-being and happiness as frivolous, as Jon Hall notes, “they’ve changed their minds.” I asked Hall where he felt the Beyond GDP movement and happiness metrics would evolve in the future:

In five years’ time I think people will be using this type of data to implement policy. In twenty years this could be very radical. Well-being could actually change the way that the machinery of government is put together. We’d have a re-alignment of how different ministries work together and how decisions are made. It will change everything.20

I also had the pleasure of interviewing Enrico Giovannini for his thoughts on well-being and happiness in regard to public policy for this book. Giovannini is the minister of labor and social policies in the Italian government under Prime Minister Enrico Letta and played a formative role in steering the OECD to focus on well-being and progress in his role as chief statistician for the organization. He launched the Global Project on the Measurement of Progress in Societies, which fostered the setting up of numerous worldwide initiatives focused on the Beyond GDP movement. For his work on the measurement of societal well-being in 2010, he was awarded the Gold Medal of the President of the Republic of Italy, and has also been a member of the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress and chair of the Global Council on the Evaluation of Societal Progress established by the World Economic Forum. I asked Minister Giovannini how he first became involved in studying issues around well-being and happiness.

In 2001, the OECD was running a project on measuring sustainable development. As an economist, I found this to be a fascinating effort. I was intrigued by the idea of integrating economics, social and environmental measures that also had an intergenerational component, and a long-term story.21

I asked the minister how he dealt with skeptics who may have thought studying well-being or happiness was impractical in light of the more financially focused metrics of the GDP.

At the beginning it was very difficult to take these ideas forward, especially with the economists and statisticians. But this has changed for several reasons. Firstly, several governments are taking these types of measures very seriously, including the French, German, Australian, Japanese, Korean, and Chinese leaders. Everybody understands that just increasing income is not enough. You have to look at all dimensions of life that include social and environmental factors.22

However, recessions and other economic issues do impact the study of well-being. As Minister Giovannini noted:

The idea of measuring and implementing happiness metrics can be very difficult to apply. During recessions a lot of people lose their jobs, which means their happiness decreases. So finding the right balance of policies, where you can look at all dimensions of a person’s life, is essential in both emerging and developed countries. However, these types of crises also push citizens to ask for policies with greater justice to allow for fair distribution of resources, along with resources that are more sustainable. So now the measurement battle around well-being and happiness is almost won, but our next step is to create policies that can include these different elements.23

Mass Happiness

“Governments aren’t put into place just to manage the GDP. Governments should make people better off.” Daniel Hadley is the director of Somerstat, a program focused on analyzing municipal needs for the city of Somerville, Massachusetts, and providing forums for direct citizen participation in civic engagement. Beyond its fame as the home of Marshmallow Fluff, Somerville has become a leader in the usage of happiness indicator metrics to drive policy change. In the New York Times article “How Happy Are You? A Census Wants to Know,” author John Tierney documents how residents were sent surveys asking people to rate both pragmatic aspects of their communities (schools, housing) as well as the beauty of the physical landscape. Overall, the city was trying to gauge the answer to the question, “Taking everything into account, how satisfied are you with Somerville as a place to live?”24

Daniel Gilbert, renowned Harvard University professor, social psychologist, and author of Stumbling on Happiness, helped Daniel and the staff at Somerville create the survey questions, which were also inspired by the work Prime Minister David Cameron has been doing in the United Kingdom with his Happiness Index. Daniel also utilized the groundbreaking work of the Knight Foundation and their Soul of the Community project to build Somerville’s survey as he told me in an interview for Hacking H(app)iness:

I borrowed from the best and specifically looked for questions that correlated with resident satisfaction. Nobody to my knowledge has combined a municipal survey with a happiness survey. We hoped we could mine the data and find out what municipal services could make people happy.25

Now that the city has collected two years’ worth of data, Daniel and his team will start to be able to analyze trends in hopes of creating a Happiness Index that could be sharable with other cities such as Santa Monica that are also working to create measures of well-being to help citizens. While a snapshot of data from one year’s survey is helpful, information from two surveys means the mayor’s office can try to implement relevant policy change based on citizen input. And this idea is already working. In one simple yet charming example, Daniel had data that the number of trees in someone’s neighborhood can affect people’s happiness. So the city planted more trees and raised resident happiness as measured by survey response.

While policy change can get caught up in bureaucratic red tape or bipartisan rhetoric, it doesn’t have to. The transparency from the Somerville surveys means the mayor’s office will need to be responsive to citizens’ requests in order to maintain trust and participation. But Daniel feels the results have been positive so far, and sees much more work to be done. From our interview:

This framework is still in its infancy. I get excited about the future. I see every city doing some version of the Happiness Index. By 2030 we’ll have metrics that will let us know that happiness shot way up in certain regions of the country. An average citizen can look at a map and see where happiness is the highest. Citizens in the future will be informed about where happiness is at its peak and why.26

As citizens we can take comfort in the fact that cities like Somerville are working to incorporate data that genuinely impacts our lives. Metrics that go beyond GDP don’t just work because they offer theoretical promise. They also have to work when put into pragmatic practice.

•

So it’s decided. While the GDP may have been a useful metric for a time, its fiscal-only focus ignores a number of issues central to accurate measurement and policy creation. It largely ignores women or people who stay at home with their kids but don’t “produce value.” While it is helpful to have any standard that the entire world agrees upon, it doesn’t make sense to cling to a metric that was developed almost one hundred years ago in a completely different time.

So, gross domestic product? Thanks for playing. But now?

Ba-BYE.