Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART I

Making a Digital Governance Framework

This section contains the fundamentals required to develop a digital governance framework and includes basic definitions, practical guidelines for development, and some of the dynamics that need to be taken into consideration when designing an organizational digital governance framework.

CHAPTER 1

![]()

The Basics of Digital Governance

Why “Governance?”

What Is Digital Governance?

Digital Strategy

Digital Policy

Digital Standards

The Power of the Framework

Your Digital Governance: How Bad Is It?

Summary

In 1995, when my son was eight months old (Figure 1.1), I packed up my family and moved to Silicon Valley to work with 500 Startups’ Dave McClure’s very first start-up, Aslan Computing. Dave had sent me a 14.4 modem and an HTML book as a baby shower gift, and coding Web pages was a good stay-at-home-mom job. At Aslan, we coded pages for the Netscape website. We invented out-of-the-box website building tools with names like “Ready, Intranet, Go!” We figured out how to manage an ISO 9001 certification process online and built lots of websites for dotcoms, most of which rose and fell quickly in the stew pot of 1990s Silicon Valley.

FIGURE 1.1

Baby Welchman circa 1995.

Late in 1996, I took a job at Cisco Systems, managing the product pages for its website (see Figure 1.2). The site was huge for its time (200K+ HTML pages), and the Web team was relatively small. There was the main site, “Cisco Connection Online,” as well as various “country pages.” Cisco was getting recognition for being a leader in ecommerce, and folks like Jan Johnston Tyler and Chris Sinton were doing pioneering work in multichannel content delivery. The whole Cisco ship was being steered by John Chambers.

Back then, corporate websites were so new, resources to manage them so few, and Web skills so ill-defined and shallow that people like me who knew only enough HTML and UNIX to be dangerous were let loose on the live production servers of major corporate websites to do whatever we wanted. At Cisco, we invented a lot. We laughed a lot. We accidently erased content a lot. (I remember accidently replacing the Cisco.com homepage with the Japanese Cisco.com homepage once.) The Web team tried almost any idea because there were no rules. The norm was to make it up as you went along. And we did. It was fun, and it couldn’t have happened any other way.

FIGURE 1.2

The original Cisco site in 1996.

But, in the years I was at Cisco, I noticed something. Cisco Systems was the epitome of all things Internet and Web. It wasn’t just that it sold routers, hubs, and switches. It wasn’t just that Cisco installed a high-speed Internet connection in its employees’ homes. Cisco as a company was serious about using the Web as a business tool. In 1996, Cisco had all its technical documentation online, downloadable software images, a robust intranet, and a rapidly growing B-to-B ecommerce model. But, despite all of this cutting-edge use of the World Wide Web, Cisco still had a lot of problems managing its own website.

There were internal debates over homepage real estate by various business units. There was an ever-present debate about who (the marketing team or the technology team) ought to be selecting and implementing key website technologies like search engine software and other, then newer, technologies such as Web content management systems and portal software. At almost every meeting about the website, more than half the time was spent not actually determining what type of functionality needed to be implemented, but on who got to decide what functionality would be implemented.

Competing factions would show up at meetings with different website designs, information architectures, and technologies, and the debate would go on and on. People would get angry. Managers would fight. Office politics raged. But after all the drama, the solution usually ended up being that no decisions were made. We left the room only to come back for rounds two, three, and four once tempers had cooled off. What that meant in practical terms was that often multiple competing technologies were deployed and multiple website designs implemented—each area implementing its own vision over the part of the site that it “owned.” The result was a graphically diverse, incongruent website with a confused information architecture.

And I was part of the problem. I was part of the marketing team that felt that we owned the whole site—because websites are communications vehicles first and foremost, right? The evil nemesis on the other side of our debates was usually the IT team, who was constantly pointing out that the website was first and foremost a technology. I wasn’t thinking about governance per se back then. But, being tasked with leading the team to select the first content management system for Cisco Connection Online, I was frequently caught straddling the line between marketing and technology. I was beginning to see that both teams had valuable contributions to make, not only in the selection process but also in the overall running of the site. Still the battles raged on.

Eventually, the cross-departmental content-management product-selection team we had assembled narrowed our candidates down to a single vendor. All the stakeholders (marketing, IT, hands-on Web folks, managers, and senior managers) assembled in a conference room. We’d written a requirements document, installed and tested the software for months over a number of use cases, negotiated pricing, and pretty much driven the vendor crazy. It was time to make the decision. Both the vendor’s implementation team and the software had passed all of our tests and the price was right, but still the people around the table were reluctant to make the commitment to buy the software.

There we were: the right people around the table, the right solution in front of us, and we still couldn’t make a decision. That’s when I began to understand what was really going on. It wasn’t that we couldn’t make a decision because we weren’t sure about what the right solution was; we couldn’t make a decision because no one really knew whose job it was to say “yes” or “no.” I also began to realize that the uncertainty didn’t stop at CMS software selection, because no one knew whose job it was to decide anything about the website: content, design, information architecture, applications, and on and on. And, without that clarity about decision-making, the extended digital team at Cisco could argue about the website pretty much in perpetuity.

The Cisco Web team had a governance problem.

In a moment I’m still proud of, I stepped forward and broke the stalemate by assuming the authority that had never been formally placed. I said, “Let’s do it. We’ll be at greater risk continuing to manage our content the way we do now than if we implement this CMS.” Thus, we moved forward.

I liked that feeling of breaking stalemates and helping Web teams move forward, and I wanted to spend more time with my four-year-old son. So I left Cisco in 1999 to become a consultant. By then, the scope of Cisco Connection was off the charts (over 10M Web pages, 200,000 registered website users, and 400 content developers worldwide). I figured if Cisco with all its Web smarts found it hard to manage its website and Web team, other companies with the same problems probably would need help as well.

They did.

Fast-forward to today. My son is in university (see Figure 1.3), and on a typical day, I pick up the phone, and it’s a call from an organization that is having trouble managing its Web presence. Maybe it’s a large, global company with over 200 websites in many different languages. Or maybe they aren’t really sure how many sites they have or who is managing them. Perhaps their main site was hacked several times last year, and some of their customer personal information has been compromised. Maybe it’s a national government trying to figure out how to govern its national Web presence. Or it could be a university with a lot of headstrong PhDs who want to do their own thing online and a student body that expects an integrated user experience from their university.

FIGURE 1.3

It’s 18 years later, and he’s on his way to university.

Usually, our conversation starts with the clients telling me how they’re going to solve their problems. I hear the same solutions all the time. Most digital and Web managers try to design their way out of a low-quality, high-risk digital presence with a website graphical interface redesign, a new information architecture, a technology replatform, or a content strategy—and everything will be better. Often, it is better for a few months or a few quarters, and then the digital system begins to degrade again. Maybe a few rogue websites have popped up, or the core digital team finds out that there are a bunch of poorly implemented social accounts. This scenario happens over and over again because organizations haven’t addressed the underlying governance issues for their digital presence.

Along with fixing websites or applications and strategizing about content, organizations need to undertake a design effort to determine the most effective way to make decisions and work together to sustain their digital face. They need a digital governance framework. But, often, when I tell organizations that (another) redesign or CMS probably isn’t going to fix their problem and that they need to take the time to address their governance concerns, I often get all kinds of pushback:

“We work in silos. That’s our culture. We don’t govern anything!”

“We need to be agile and innovative. Governance just slows things down.”

“We don’t have time to design a digital governance framework.

We’ve got too many real problems with our website.”

In the face of a 15- or 20-year-old technically incongruent, content-bloated, low-quality website, here’s my challenge:

• Isn’t it better to take the time to come up with some basic rules of engagement for digital than to deal day-in and day-out with unresolved debates over content site “ownership,” graphics, social media moderation, and the maintenance websites?

• How many lawsuits, how many security breeches, and how many customers and employees do you have to annoy before you realize that governing your digital presence makes sense?

• What’s the bare minimum that needs to be controlled about your digital presence in order to manage risk, raise quality, and still allow different aspects of the organization the flexibility they need?

Isn’t governance the better choice?

Why “Governance?”

I’m often asked if I can find a more user-friendly word than “governance.”

No, I can’t.

For many, the word “governance” conjures up an image of an organizational strait jacket. Governance to them means forcing people to work in a small box or making everyone work the same way. They’d rather have me use words like “team building” or “collaboration model.” I usually refuse. Governance is good. And, after reading Managing Chaos and applying its guidance to your own organization, I hope you’ll agree. Governing doesn’t have to make business processes bureaucratic and ineffective. In fact, I’d argue that “bureaucratic and ineffective” describe how digital development works in your organizations right now—with no governance.

Governance is an enabler. It allows organizations to minimize some of the churn and uncertainty in development by clearly establishing accountability and decision-making authority for all matters digital. That doesn’t mean that the people who aren’t decision makers can’t provide input or offer new and innovative ideas. Rather, it means that at the end of the day, after all the information is considered, the organization clearly understands how decisions will be made about the digital portfolio.

There are many different ways to govern an organization’s digital presence effectively. Your job is to discover the way that works best for your digital team. Your digital governance framework should enable a dynamic that allows your organization to get its digital business done effectively—whether you’re a bleeding-edge online powerhouse or a global B-to-B with a bunch of slim “business card” websites. A good digital governance framework will establish a sort of digital development DNA that ensures that your digital presence evolves in a manner that is in harmony with your organization’s strategic objectives. A digital governance framework isn’t bureaucratic and ineffective. Properly designed, a digital governance framework can make your online business machine sing.

The proof is out there. Wikipedia is, arguably, one of the most substantively and collaboratively governed websites on the Web, but it is also perceived as a site that fosters a high degree of freedom of expression. The well-defined open standards of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) enable the World Wide Web to exist, as it is—without which we would not even be having this conversation. And the multiplicity of purpose and diversity apparent on the World Wide Web speaks for itself.

Your organization needs its own internal W3C, so to speak, so that departments, schools, lines of business—however you segment your organization—can be free to take advantage of digital channels, but within parameters that make sense for the organization’s mission, goals, and bottom line. In addition, it needs to intentionally design its digital team so that it can work efficiently and productively. And that’s the work of a digital governance framework.

This is your chance to establish the foundational framework that will influence the direction of digital in your organization for years to come. Business leaders and senior digital leaders need to get together and establish how to govern and manage digital effectively in their organizations. Now. Through Managing Chaos, you will learn how to free your organization from debate-stalled stagnation around digital development and establish an environment where an entire organization can work together to successfully leverage all that digital has to offer.

What Is Digital Governance?

Digital governance is a framework for establishing accountability, roles, and decision-making authority for an organization’s digital presence—which means its websites, mobile sites, social channels, and any other Internet and Web-enabled products and services. Having a well-designed digital governance framework minimizes the number of tactical debates regarding the nature and management of an organization’s digital presence by making clear who on your digital team has decision-making authority for these areas:

• Digital strategy: Who determines the direction for digital?

• Digital policy: Who specifies what your organization must and must not do online?

• Digital standards: Who decides the nature of your digital portfolio?

When these questions are answered and your digital governance framework is well implemented by leadership, your organization can look forward to a more productive work environment for all digital stakeholders and a higher-quality, more effective digital presence.

The work of the framework is to clarify who the decision makers are, but in order to understand who should decide matters related to strategy, policy, and standards, it’s important first to understand what these things are.

Digital Strategy

A digital strategy articulates an organization’s approach to leveraging the capabilities of the Internet and the World Wide Web. A digital strategy has two facets: guiding principles and performance objectives.

• Guiding principles provide stakeholders with a streamlined, qualitative expression of your organization’s high-level digital business intent and values.

• Performance objectives quantitatively define what digital success means for an organization.

If your digital strategy is off target, then supporting policy, standards, and the process-related tactical machinations of your digital team will likely be off target as well. So when you are identifying who should establish digital strategy for your organization, it is especially important to include the right set of resources. That set should include the following:

• People who know how to analyze and evaluate the impact of digital in your marketspace.

• People who have the knowledge and ability to conceive an informed and visionary response to that impact.

• People who have the business expertise and authority to ensure that the digital vision is effectively implemented.

In most organizations, your digital strategy team will need to be a mix of executives and senior managers, business analysts, and your most senior digital experts. Luckily, identifying those resources is relatively easy. In fact, right now you could probably sit down and write down your “dream team” for establishing digital strategy. But that’s only half of the challenge. Often, the real digital strategy challenge is getting those resources to communicate and work together. The skill sets, experience, work styles, and business language of these two constituents can be very different, and the managerial distance between executives who mandate organizational change and digital experts who implement it can be great. In Chapter 3, “Digital Strategy: Aligning Expertise and Authority,” I will focus not only on selecting the right players for establishing digital strategy, but also on how to get that team aligned.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Ensure that your digital strategy takes into account business considerations, as well as your organization’s culture toward digital. Not every organization needs to be a ground-breaking, digital go-getter.

Digital Policy

Digital policies are guidance statements put into place to manage risk and ensure that an organization’s core interests are served as it operates online. Think of policies as guardrails that keep the organization’s digital presence from going off the road.

The substance of digital policy should influence the behavior of employees when they are developing material for online channels. For example, the policy might specify that developers should not build applications that collect email addresses of children, because the company doesn’t want to violate their organization’s online privacy policy regarding children. Or perhaps content developers at a pharmaceutical company might be made aware of the differences in national policy as it relates to talking about the efficacy of their products online.

Because digital policy is a subset of corporate policy, it naturally inherits the corporate policy’s broad scope and diversity. Due to this scope and diversity, typically, a single individual or group cannot effectively author policy. This approach sometimes comes as a surprise to digital teams who feel that policy authorship falls naturally into their camp. That scenario occurs because organizations often conflate policy and standards; however, the two areas are not the same. Policies exist to protect the organization. They do not address online quality and how to achieve it—that is the role of standards.

A digital governance framework ought to designate a policy steward who is accountable for ensuring that all digital policy issues are addressed. Digital policy steward(s) should have a relatively objective, informed, and comprehensive view of the implications of digital for the organization. Digital policy authors are a diverse set of organizational resources who can contribute to and shape an appropriate organizational position for a given policy topic. In Chapter 4 “Staying on Track with Digital Policy,” I’ll go into more detail about the responsibilities of the policy steward and offer suggestions for which person or people ought to be authoring policy within organizations.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Forget that digital policy is a subset of corporate policy and needs to be in harmony with other policies within your organization. For instance, digital policy is often informed by fiscal policy, IT policy, or vertical, market-focused external policy.

The Five Guiding Principles of Wikipedia1

Wikipedia is a free encyclopedia, which is written by the people who use it in many different languages, as you can see in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4

Wikipedia: an encyclopedia for the world.

The “Five Pillars” of Wikipedia (an online free encyclopedia) represent a great example of how to design guiding principles for an organization. These pillars/principles capture the culture, values, and goals of the organization as it relates to the Wikipedia digital properties, and they provide clear directions to the Wikipedia development community. They are as follows:

Wikipedia is an encyclopedia.

It combines many features of general and specialized encyclopedias, almanacs, and gazetteers. Wikipedia is not a soapbox, an advertising platform, a vanity press, an experiment in anarchy or democracy, an indiscriminate collection of information, or a Web directory. It is not a dictionary, a newspaper, or a collection of source documents, although some of its fellow Wikimedia projects are.

Wikipedia is written from a neutral point of view.

We strive for articles that document and explain the major points of view, giving due weight with respect to their prominence in an impartial tone. We avoid advocacy, and we characterize information and issues rather than debate them. In some areas, there may be just one well-recognized point of view; in others, we describe multiple points of view, presenting each accurately and in context rather than as “the truth” or “the best view.” All articles must strive for verifiable accuracy, citing reliable, authoritative sources, especially when the topic is controversial or a living person. Editors’ personal experiences, interpretations, or opinions do not belong.

Wikipedia is free content that anyone can edit, use, modify, and distribute.

Since all editors freely license their work to the public, no editor owns an article, and any contributions can and will be mercilessly edited and redistributed. Respect copyright laws, and never plagiarize from sources. Borrowing non-free media is sometimes allowed as fair use, but strive to find free alternatives first.

Editors should treat each other with respect and civility.

Respect your fellow Wikipedians, even when you disagree. Apply Wikipedia etiquette and avoid personal attacks. Seek consensus, avoid edit wars, and never disrupt Wikipedia to illustrate a point. Act in good faith and assume good faith on the part of others. Be open and welcoming to newcomers. If a conflict arises, discuss it calmly on the nearest talk pages, follow dispute resolution, and remember that there are 4,261,587 articles on the English Wikipedia to work on and discuss.

Wikipedia does not have firm rules.

Wikipedia has policies and guidelines, but they are not carved in stone; their content and interpretation can evolve over time. Their principles and spirit matter more than their literal wording, and sometimes improving Wikipedia requires making an exception. Be bold, but not reckless, in updating articles, and do not agonize about making mistakes. Every past version of a page is saved, so any mistakes can be easily corrected.

1 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Five_pillars

The Range of Digital Policy

Table 1.1 outlines the basic areas for policy consideration. Some organizations will need to address a more comprehensive set of policies based on their objectives or digital audience. For instance, organizations that support a digital presence for young children may have a specific children’s online privacy policy, or those people in healthcare may have to directly address patient and medical information that is related to privacy concerns. In fact, sometimes policies might have to be drafted to address constraints related to particular geographic regions such as states, nations, and unions.

TABLE 1.1 A LIST OF BASIC DIGITAL POLICY

|

Policy Topic |

Description |

|

Accessibility |

Details the accessibility level that must be followed to ensure that all users can interact with your organization online. |

|

Branding |

Determines how your organization maintains its desired identity while online. |

|

Domain Names |

Manages the purchase, registration, and use of Internet domain names. |

|

Language and Localization |

Establishes parameters for language used in conducting business online and special information related to making content appropriate for locales globally. These include translation, idiom usage, imagery, and so on. |

|

Hyperlinks and Hyperlinking |

Determines how and when it is appropriate and inappropriate to hyperlink to content on the World Wide Web within and external to the organization. |

|

Intellectual Property |

Covers copyright and other ownership for information gathered, delivered, and used online. |

|

Privacy |

Covers the privacy needs of employees and users when interacting with the organization online. Specific technologies that are unique to the Web (like “cookies” and other tracking devices) are defined and their use discussed. |

|

Security |

Defines measures that will be taken to ensure that information delivered online (and used in transactions) and provided by customers and employees is used in the manner intended and not intercepted, monitored, used, or distributed by parties not intended. |

|

Social Media |

Addresses parameters for the use of social software within the organization. |

|

Web Records Management |

Specifies the full lifecycle management of content delivered and generated on the World Wide Web. May also include the disposition of transactional log files. |

Digital Standards

Standards articulate the exact nature of an organization’s digital portfolio. They exist to ensure optimal digital quality and effectiveness. Standards are both broad and deep. They address a broad range of topics with depth, such as overall user experience and content strategy concerns, as well as tactical specifications related to issues like a website’s component-based content model or replicable code snippets. That’s a lot of territory to cover. So, usually, it will take an equally broad and deep range of resources to contribute to and define digital standards.

Often, when I am brought in to resolve organizational governance concerns, the root of the problem is a disagreement about who gets to define those standards. Sometimes, the disagreement can be quite contentious with various righteous digital stakeholders coming to the debate armed with expertise (Web team), platform ownership (IT), and budget and mission (business units and departments)—all equally sure that they should be the final decision-maker.

A digital governance framework gives each of these stakeholder types an appropriate role to play in the definition of standards. In Chapter 5, “Stopping the Infighting About Digital Standards,” I’ll explore in detail how to assign stewardship and authorship to standards. When these roles are assigned, time-consuming debates about functionality will be minimized and an environment of collaboration for a better digital quality and effectiveness will emerge.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Make sure that you document the full range of digital standards, which includes design, editorial, publishing and development, and network and server standards. Often, digital workers just focus on editorial and design standards and neglect the other categories.

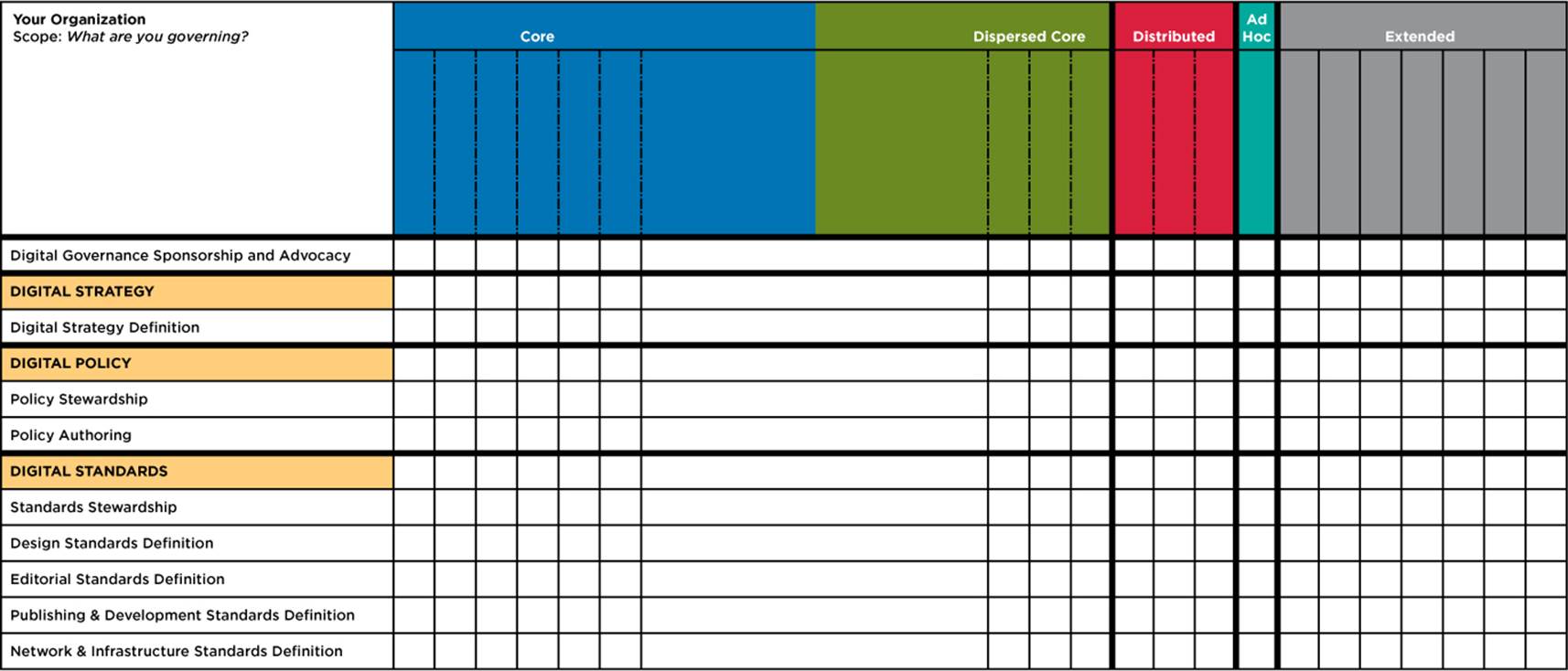

The Power of the Framework

A digital governance framework is a system that delegates authority for digital decision-making about particular digital products and services from the organizational core to other aspects of the organization, as shown in Figure 1.5. Digital governance frameworks have less to do with who in your organization performs the hands-on work of digital and more to do with who has the authority to decide the nature of your websites, mobile apps, and social channels. That means a digital governance framework does not specify a production process. It does not articulate a content strategy, information architecture, or whether or not you work in an agile or waterfall development environment. What a digital governance framework does is specify who has the authority to make those decisions. This explicit separation of production processes from decision-making authority for standards is what gives the framework its power.

If you consider your own situation, it’s likely that most organizational debates about digital are not about who does the work, but rather about the way your websites look or what digital functionality should or should not be built and how those efforts are funded. In my experience, most digital stakeholders are so disinterested in doing the day-to-day grunt work of digital that a relatively small, central digital team is completely overburdened by tactical development tasks, while an army of digital stakeholders (who want to put little or no resources, fiscal or human, and effort into ensuring the work gets done) use their organizational authority to dictate how websites should look, which applications should be developed, and which social channels ought to be supported. This unbalanced situation leads to a contentious, resentful work environment, and more importantly, to a low-quality, ineffective digital product. The overburdened digital team stays in this situation because doing all the work is often the only way they can ensure that best practices and their standards are adhered to—because there is no governance framework, and the only way they can ensure standards compliance is by doing all the work themselves.

Having a digital governance framework brings digital development back into balance by separating day-to-day digital production functions and decision making for strategy, policy, and standards. For a long time, daily Web page maintenance and responsibility for the look-and-feel and functionality of websites has been concentrated in the hands of a few people in the organization. Perhaps this strategy was effective in the early days of digital production. But, today, with a more complex digital presence that includes not just websites but also mobile and social software interactions, digital production needs to be distributed throughout the organization. In order for production decentralization to be done effectively, a strategy and policies and standards need to be clearly communicated so that all people working with digital know what to do and what not to do. A digital governance framework provides that clarity.

FIGURE 1.5

The digital governance framework accountability grid.

When this effective decentralization of production happens, two important things occur:

• The workload and expense of digital developing is shared throughout the organization.

• The organization can leverage the knowledge assets of their entire organization to inform and support its digital portfolio.

And that’s really powerful.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Understand where you are on the digital maturity curve before you start your framework design effort. Most organizations can’t make the leap from chaotic digital development environment to a responsive one in a single bound!

The Range of Digital Standards

When you establish decision-making authority for standards, you will discover that it takes collaboration among resources with a broad range of competencies in order to create an effective set of standards that work together (see Table 1.2).

TABLE 1.2 DIGITAL STANDARDS CATEGORIES

|

Standards Domain |

Influence Over |

|

Design The graphical presentation layer of digital. |

Interactive (video design, podcasts, forms, applications) Typography and Color (symbols, bullets, lists, fonts typeface and size, color palette) Templates (page components, pop-up windows, tables, email) Images (background images, photos, buttons, and icons) |

|

Editorial The style of language and the strategy for content delivery and curation. |

Branding (tone, use of company name, use of product names) Language (style manual/dictionary, terminology, cultural competence) Localization (translation, management, cultural adaptation) |

|

Publishing and Development Information management, development protocols, and publishing and infrastructure tools that impact the architectural aspects of information organization and delivery. |

Information Organization and Access (information architecture, taxonomy, metadata, file-naming conventions, Web records management, accessibility) Tools (portal, Web content management, search, translation management, document management, collaboration, digital asset management, surveying, webcasts, social software, Web analytics, usability) Development Protocols (RSS links and specifications, multimedia, operating systems, browser compatibility, browser detection, load time, single sign-on, mobile, password management, FTP, frames, personal data collection, code, file types, cookies and sign-in, personal data retention, non-HTML content) |

|

Network and Server The platform-focused aspects of digital production. |

Domains (domain format/names, use of domain name, domain name redirects, vanity/marketing domains) Hosting (site backup, disaster recovery, supported connection speed, personal data retention) Security (personally identifiable information, ebusiness/financial transactions, security protocols to protect information, visitor data and traceability, firewall rules, data safety and transmission intrusion detection, alerting mechanism, monitoring mechanism SSL, passwords, time-outs and auto log-offs) Server Software (databases, DB naming conventions, app server, Web server, virtual private network [VPN], operating system, domain name server, load balancer, file server, maintaining licensing keys, single sign-on, server analytics, wireless application protocol [WAP], maintaining warranties and servicing) Server Hardware (standard Web server configuration, database, app server, Web server, firewall appliance, maintaining warranties and servicing, test servers, caching) |

Your Digital Governance: How Bad Is It?

Rest assured—every organization has digital governance problems. Just because an organization might look good online doesn’t mean that it is getting a good return on its investment or operating in an effective, low-risk environment. I’ve seen plenty of “lipstick-on-pig” digital environments where a nice-looking website design was only thinly veiling an ineffective digital presence supported by no real digital strategy and an uncoordinated digital team—governance gone wild! I’ve also seen some “looks like it was built in 1997” websites where the site was getting real work done for the organization, and the supporting organization was only inches away from governing well. Looks can be deceiving.

How can you tell how well your organization is doing? Instead of looking at your (and your competitor’s) websites, social channels, and mobile apps to judge how well you are governing, you can understand where you are on the digital governance maturity curve (see Table 1.3).

You’ll probably find that your organization is at different levels of maturity for different aspects of the framework (team structure, digital strategy, digital policy, and digital standards). That’s normal. Maybe you work in a heavily regulated industry, and you’re “mature” when it comes to digital policy, but you lack standards. Or maybe you have some policy and standards, but you have no real digital strategy. The point is for you to assign responsibility and accountability to the right set of resources so that the substance of your strategy, policies, and standards is on target, laying the foundation for your digital team to create real online value for the organization.

Once you’ve finished designing your framework, you will find that accountability and authority for strategy, policy, and standards will be distributed throughout your organization’s digital team. But do you know who your digital team is and what they do? Maybe not. So before we examine how to determine accountability for each of the digital governance components, let’s take a look at how digital teams are structured. Just as websites grow organically and without much of a plan, so do digital teams. It’s important to take the time to establish and put into place a well-defined digital team before you begin your governance design efforts.

Understanding Digital Governance Maturity

There is a digital governance maturity curve (see Figure 1.6) that most organizations move through when they launch a digital channel (Web, mobile, or social). The process of maturity begins with the decision to launch a new channel, and it culminates with the organization having fully integrated that channel into the company to the extent that governing dynamics and operational processes are automatic, leaving the organization fully responsive to digital trends.

The dynamics of each phase are fairly distinct. Most organizations that are seeking to improve digital governance are usually in the “chaos” phase, while some are stalled at “basic management” and trying to move to the next level. Also, organizations are typically at different places on this curve, depending on which digital channel is being considered. For example, an organization might be at “basic management” for websites, but at “launch” for its mobile channel, while in “chaos” for social channels. This issue can add complexity when designing a digital governance framework.

FIGURE 1.6

The digital governance maturity curve.

GOVERNANCE AND DIGITAL ANALYTICS

Phil Kemelor, EY

In my work with Fortune 500 companies, government agencies, and national non-profit organizations, the linkage between smart Web governance and intelligent use of analytics data goes hand-in-hand. Governance sets the tone for a culture of analytics through clear definition of strategy and direction as to what metrics and measurement guide accountability in achieving goals related to the strategy.

TABLE 1.3 WHERE IS YOUR ORGANIZATION ON THE DIGITAL GOVERNANCE MATURITY CURVE?

|

Maturity Stage |

Dynamics |

|

Launch |

Research and development mode, as the digital functionality or channel is being informally tested or formally piloted. |

|

Basic policy constraints are considered to ensure that the organization is operating within the bounds of the law and any other regulatory constraints. |

|

|

There are few standards imposed at this point because the organization is just going to “try out” new functionality to see if there is value to the organization. |

|

|

Organic Growth |

Aspects of functionality “work.” Others in the organization begin to leverage the work of the piloting team. |

|

Functional and systemic redundancy begins (design, technology, process). |

|

|

Some progressive executives may understand the value of the channel, but deep value and mature business measurement tactics are not being applied. |

|

|

Functionality is thought of as a “cost center,” not a core revenue generator. |

|

|

Basic policy constraints are still in place, and some may be documented. |

|

|

There are usually few standards in place. Considerations around basic corporate standards, such as branding, begin to arise. |

|

|

Chaos |

Executives and senior management are aware of the digital channel, but they have likely wholly delegated the creation of digital strategy to junior resources. |

|

Different organizational departments have created organizationally incongruent digital strategies. Competition for “ownership” begins to emerge. |

|

|

The organization is unable to identify and account for all its digital assets or the people who execute on and fund digital development inside the organization. |

|

|

Core marketing communications and IT policy are beginning to be formalized—sometimes separate from the stewardship and influence of the corporate legal team. |

|

|

Some standards are documented, but many core digital standards are missing. |

|

|

Basic |

Executives and senior digital experts have begun a dialogue regarding the strategy for digital. |

|

The organization begins to consider its digital budget. |

|

|

Digital quality measurement tactics, systems, and software are emplaced. |

|

|

Some design, functionality, and platform normalization has begun, and efforts are made to reduce redundancies where they exist and where it is effective. |

|

|

A core digital center of excellence is beginning to emerge, although it may not have all of the desired authority. |

|

|

Performance is evaluated by examining tactical analytics like website “page hits” and number of “likes” in social media channels. |

|

|

The existence of a set of digital policies and standards is in place. |

|

|

Basic cross-organization collaboration teams begin to appear, such as “Web Councils” and standards development teams. |

|

|

Responsive |

“Digital” is fully integrated within the organization and is no longer a functional silo. |

|

The digital team is clearly identified, organized, and funded. |

|

|

Accountability for digital strategy is clearly placed. |

|

|

A guiding principle for digital development is established. |

|

|

Performance indicators are defined, and mechanisms and programs for quality and success measurements are in place. |

|

|

Digital policy stewards and policy authors are identified. |

|

|

The process for external and internal policy review is in place. |

|

|

Digital standards steward(s) and authors are identified, and standards compliance and measurement mechanisms are implemented. |

Summary

• Digital governance is a framework for establishing accountability, roles, and decision-making authority for an organization’s digital presence. It addresses three topics: strategy, policy, and standards.

• Digital strategy articulates the organization’s approach to leveraging the capabilities of the Internet and World Wide Web. It is authored by those who can evaluate the impact of digital on your marketspace and come up with an effective strategy for success.

• Digital policies are guidance statements put into place to manage the organizational risk inherent with operating online. They should be informed by digital, organizational, and legal experts.

• Digital standards are guidance statements for developing the organizational digital presence. They should be informed and defined by subject matter experts.

• A digital governance framework delegates authority for digital decision-making about particular digital products and services from the organizational core to other aspects of the organization. This allows the organization to effectively decentralize production maintenance of its digital presence.

out our premium features.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.