Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART II

Case Studies

CHAPTER 10

![]()

Government Case Study

Pre-Framework Dynamics

Our Overall Framework Recommendation

Web Team Findings and Recommendations

Web Strategy and Governance Advocacy Findings and Recommendations

Web Policy Findings and Recommendations

Web Standards Findings and Recommendations

Two Years Later

When we met this government organization (unidentified due to privacy issues), it was locked in a stalemate over who had authority over the look-and-feel and information architecture of its website. Certain aspects of the organization were attempting to implement a new, more integrated information architecture, and other digital stakeholders were not convinced of the proposed direction and were actively resistant. Their rationale was that the audience for the organization was too diverse to be supported by a unified information architecture and (some thought) brand identity. One team had actually created a brand new website (content and everything), but was unable to deploy it because the other team thought it was inadequate to meet the organization’s needs. The Web team was caught in the middle of this debate and sought guidance to help resolve the situation. Their focus was Web only, and for this engagement, social media and mobile were intentionally excluded to avoid complexity.

To break the stalemate, we worked with the organization to create a Web governance framework for its public facing websites. The process for creating the framework included some (sometimes difficult) group conversations and workshops around policies and standards development. The team also worked internally to establish more effective communications protocols and processes across business lines.

While there was a lot of noise around the website redesign when we arrived, we were quick to notice that this was an organization with very mature processes and procedures. Also, culturally, the organization understood the values of protocols and standards. These organizational characteristics helped them to become what we felt to be one of our best success stories as it related to digital governance in a governmental organization. Many large (10K+ employees) governmental organizations have similar dynamics, but sometimes the culture or management approach is less disciplined. In those situations, implementing a governance framework can be an exceptional challenge, even when all the stakeholders agree that changes in governance need to be made. So, in this case, the very rigidity that led to their governance problems was also the source of their solution. Once the framework was defined and emplaced by leadership, the organization had a relatively easy time with implementation.

Pre-Framework Dynamics

There were very strong (and negative) opinions about digital governance in the organization. But there were two overriding themes that crystallized as we spoke with stakeholders:

• “We don’t need governance.” Many in the organization felt that a Web governance framework was not applicable because the mission of the organization’s business units was too varied to support any kind of unified vision. In essence, they felt that the organization should have an array of websites that weren’t necessarily related to each other in design or intent.

• “It won’t work here.” Of those people who did think that there was value in establishing mature digital governance practices, many thought that governance wouldn’t work inside their organization because there were too many power brokers and independently funded silos.

These dynamics were bypassed in large part because the Web governance effort was supported by an executive level advocate who funded the digital governance project and insisted upon some of the implementation recommendations. Once the power of the framework took hold, all stakeholders could see that operating within the framework was easier and led to faster digital delivery.

Our Framework Recommendation

Overall, we recommended that this organization create a simple hub-and-spoke Web team model. The core of this team would be split between the marketing communications function and IT. The core team would maintain all key infrastructure systems like Web content management, the portal, and search engines. They would also be responsible for defining standards for the look and feel of the website. Departmental Web managers would be established and trained in order to create domain-specific departmental content. Legal teams would play a role as we formalized Web policy. The hardest aspect of this framework was the standards definition. While a simple resolution was eventually established, it took a lot of teamwork and discussion to get to the results outlined in Figure 10.1.

Due to the collaboration around the creation of the governance framework, the implementation was straightforward. The government plan was formalized at a senior level and implemented over 18 months.

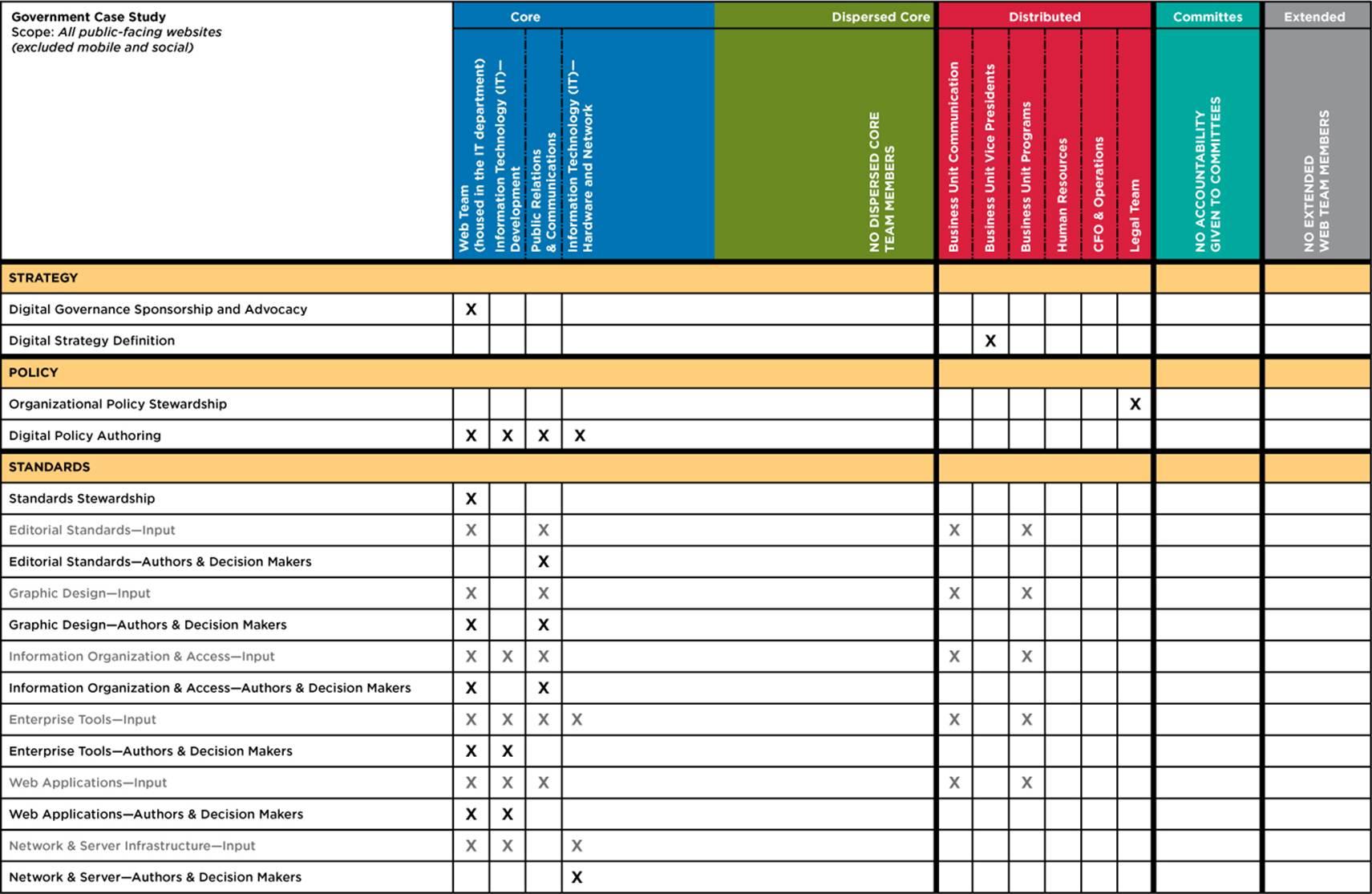

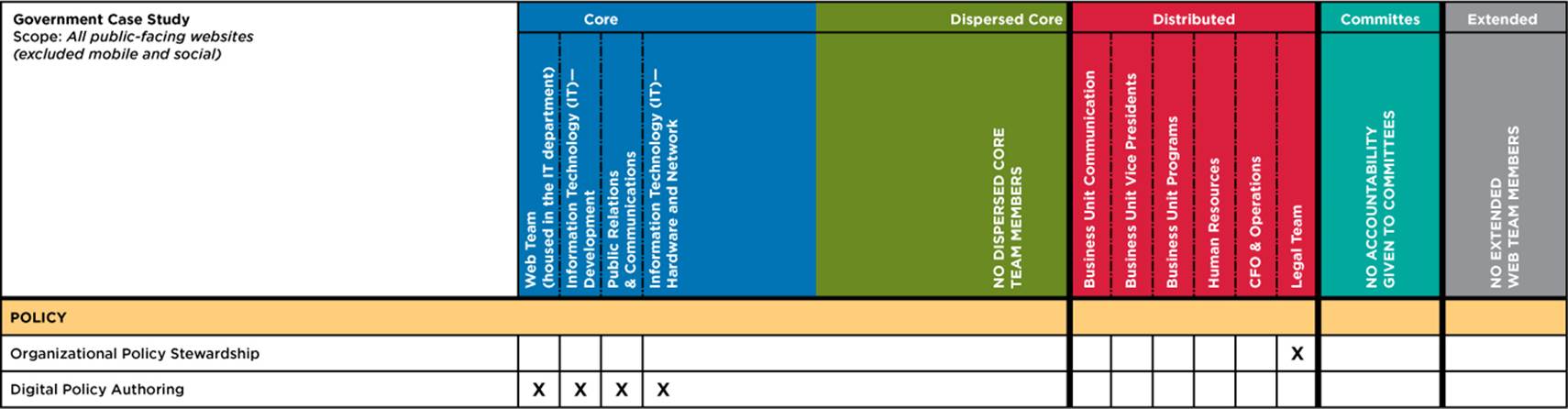

FIGURE 10.1

Potential government digital governance framework.

Web Team Findings and Recommendations

The key Web team dynamics that we found in this government agency were somewhat typical; however, we felt that the finger-pointing at the core digital team as the root of all online quality concerns was unfair. The team had never been given any real authority to address overall website quality. In fairness, the entire organization had never holistically addressed the structure and skill set of the de facto core Web team, and we felt that it was inappropriate to attack that team for what was an organizational deficit.

The digital skill sets in the distributed team components were, on the whole, weaker than those of the resources on the core team. However, those departmental players were very influential politically and could influence the direction of the digital work stream in substantive ways. Some notable dynamics were the following:

• The primary production-focused Web team was housed within the IT department and liaised regularly with resources in communications and public relations and business unit program offices. They put up content that others in the organization created.

• Many people inside the organization questioned the competence of the core Web team. The criticism focused on basic competence: Did they really know how to make a good website? Other criticism centered on whether or not non-domain experts could curate a website with specialized content. The sentiment being expressed was that domain-specific knowledge experts ought to manage the website.

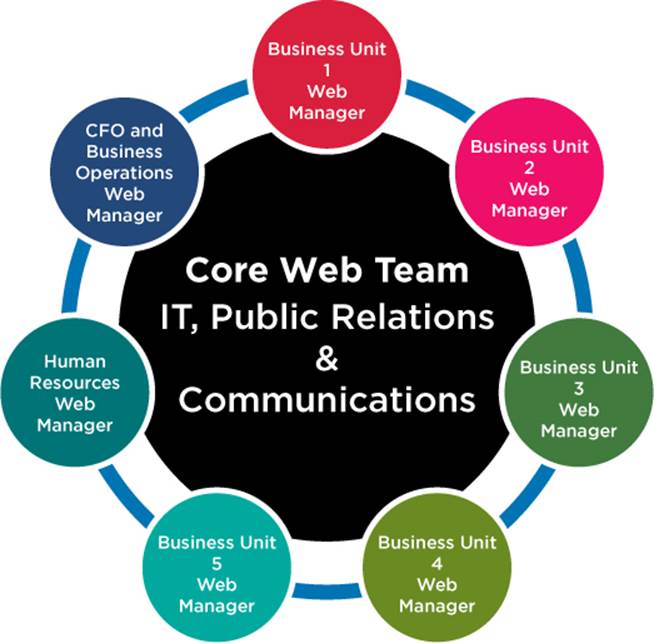

FIGURE 10.2

Recommended Web team structure.

• The core Web team was not properly staffed. There were missing skill sets of the team members, and the team was more focused on day-to-day production rather than strategically focused on how the Web and other online channels could support the organization in meeting its goals.

• There were resources outside of the primary Web team that also had some skills in Web development. They often challenged the core Web team’s authority in ways that were sometimes less than constructive, such as creating “rogue” websites that did not necessarily follow standards or best practices outlined by the core Web team.

This organization did not have a complex Web presence. There was no multilingual component aspect to the website. So areas like translation management and the workflow processes associated with it were not a factor. There were some legacy organizational units, which added some complexity, because these organizational units were not able to be dissolved, even though it seemed as if they had served their purpose and there might be a more streamlined way to manage some of the workflow processes they supported. At the end of the day, though, none of these shifts would made a difference to the digital governance or website quality. So, in order to ease implementation, we worked around this little bit of organizational complexity (see Figure 10.2).

We like to see stand-alone Web and digital teams, and this organization had one. What was unusual was that it was housed in the IT department. Usually, refined stand-alone digital teams are housed in the marketing communications departments. However, the placement of this team in IT strengthened it. IT had access to more robust funding mechanisms, and it had a more mature perspective on policy than we usually see with digital and Web teams that are housed in marketing communications teams. This is due to IT’s responsibility to establish digital policy as it relates to privacy and security. Core team functions were split among the following teams with overall core team leadership from the Web team component within IT.

• Public Relations and Communications

• Web Team (housed in the IT department)

• Information Technology (IT): Development

• Information Technology (IT): Hardware and Network

Distributed Web Team

We recommended that each department Web team establish a Web manager who would be responsible for interfacing with the core Web team (see Figure 10.3). The primary responsibilities of the business unit Web managers would be content creation and maintenance. Each business unit was made responsible for funding this role. In most instances, the business units chose to fill this role with personnel from communications. Some of them hired more than one resource to fill this role, particularly if they were more active on the Web. Application development and other non-content-related production and development functions were executed from within IT components that supported the departments. Both communications and IT components followed the standards established by the core team when creating content and applications.

FIGURE 10.3

Recommended distributed Web team members.

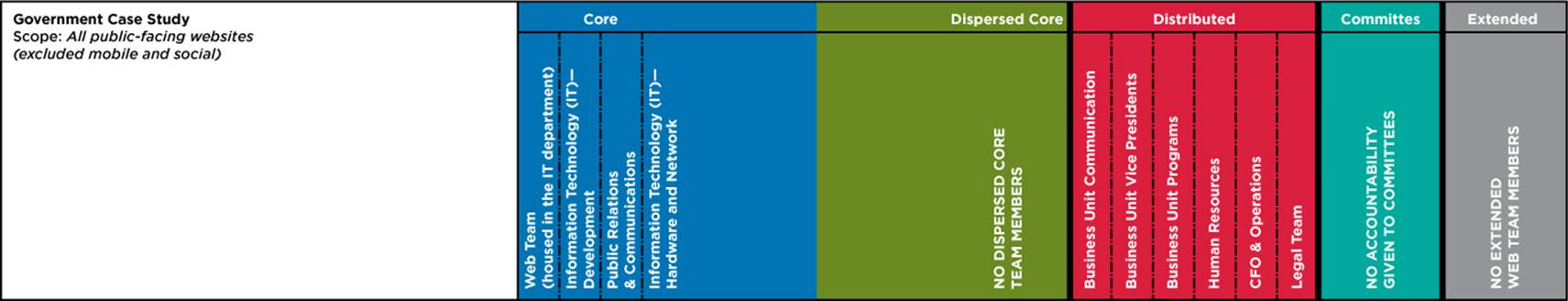

Web Strategy and Governance Advocacy Findings and Recommendations

In this engagement, Web strategy really was a key. All of the stakeholders within this organization felt that they should create their own Web strategy—one that aligned with the goals and objectives of their particular business unit. But their sense of Web strategy was limited. What they really wanted to do was decide what their part of the organizational website looked like. They weren’t really interested in quantifying the value the website provided to the organization or how to better operationalize aspects of the organizational agenda with the use of online tools. In some ways, this was appropriate, as there was no real obvious use case for sophisticated citizen-facing digital functionality. Still, we would have liked to see more maturity in this area. Summarized, the key findings for the Web strategy were:

• Web strategy at its highest level was not addressed. “Web strategy” inside the organization was synonymous with website structure and the look-and-feel of the site.

• There was no real sense of guiding principles or success and performance indicators.

• The executive tier was largely strategically disengaged from digital and had only been brought to the table due to a large debate regarding the look-and-feel of the public website.

• There was strong advocacy of and a call for Web governance from the very top of the organization. Leadership did not like a website stalemate and wanted the problem solved.

We recommended that accountability for Web strategy be placed at a senior management level (see Figure 10.4). Already business unit/departmental senior managers met regularly. We simply added the Web agenda to their conversation. In the future, this team will discuss how to best leverage the website in order to support the organization.

Also, this group and representatives for the core Web team will meet annually to revisit the government agency’s guiding principles and ensure that they are in harmony with their organizational goals and content, data, and technology capabilities. This review was incorporated with other organization-wide objectives and metrics to ensure congruence and lack of redundancy across business unit Web efforts.

FIGURE 10.4

Recommendations for Web strategy accountability.

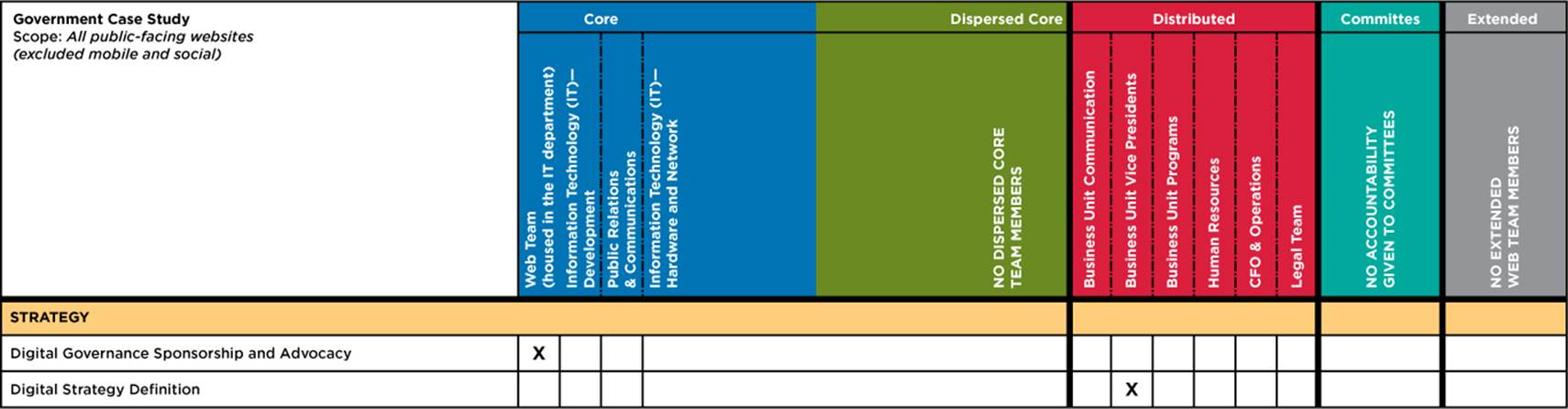

Web Policy Findings and Recommendations

We were delighted to find a legal team that was firmly engaged with digital policy. To date, the team probably had one of the most complete approaches to digital policy we have seen in our client pool. The key dynamics were:

• Web policy stewardship was not named as such, but the function was filled by the legal team. It’s worth noting that this was the first organization we worked with where a member of the legal/policy team showed up for the governance framework kick-off meeting fully prepared to address policy concerns.

• Many policies had been written, particularly the IT-centered polices around privacy and security. However, many other Web-specific or content-related policy had yet to be authored. So the team needed to examine a more comprehensive list of digital policies, which they did.

We recommended that the legal team formally take on the role of policy stewards (since they were already doing such a great job). Going forward the legal team would solicit input from policy authors for subject-matter-specific content (for example, information related to branding or technological capabilities). After policies were drafted, they would be codified through the normal organizational policy codification process at the organization and referenced on the employee intranet (see Figure 10.5).

FIGURE 10.5

Recommended policy accountability.

Standards authors: (policy authoring would be broken out among the following teams):

• Public Relations and Communications

• Web Team (housed in the IT department)

• Information Technology (IT): Development

• Information Technology (IT): Hardware and Network

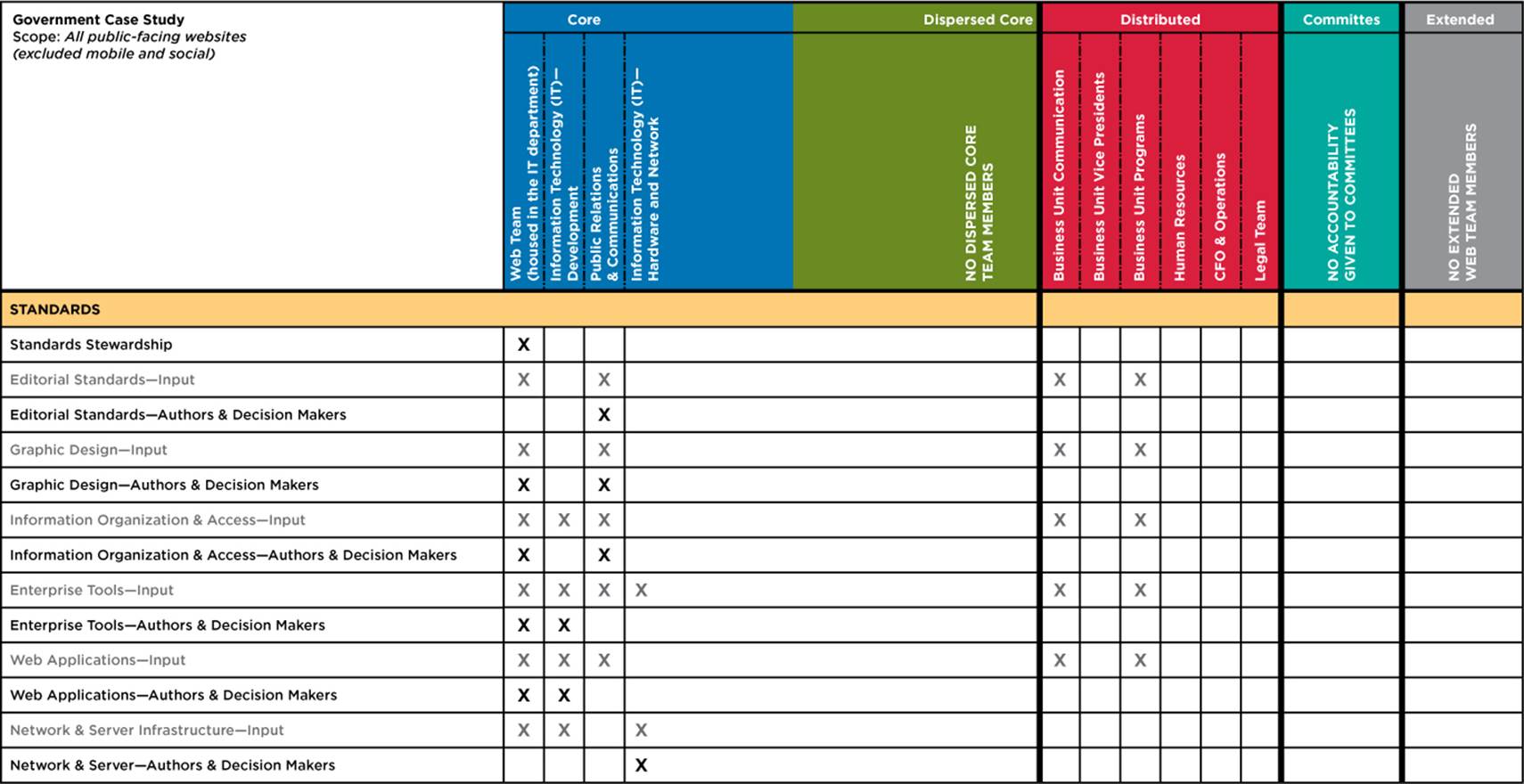

Web Standards Findings and Recommendations

Digital stakeholders were engaged in the typical debate around who gets to determine website standards. As with the strategy component, all stakeholders felt that they should be able to establish their standards locally in their own department. After the initial framework engagement, we did a more substantial drill down on roles and responsibilities around website standards. Those roles have been adopted, and the debates have ceased. Some particular Web standards dynamics were:

• There was no steward for digital standards identified.

• The organization had strong standards for design and editorial.

• Standards related to information organization and access, Web tools and applications, and network and server infrastructure standards were weaker.

• Most of the standards’ lifecycles (define, disseminate, implement, and measure) were largely unaddressed.

• Due to a lack of maturity in standards, there was a lot of debate around things like the look-and-feel of the site and what sorts of infrastructure tools, like Web content management systems and search engines, ought to be procured and implemented.

Once most of the concerns regarding standards ownership were aired, we introduced the concept of input versus decision-making. The team adopted the following responsibilities with ease:

Standards Steward: Web Team (housed in the IT department). See Figure 10.6.

FIGURE 10.6

Web standards roles.

Standards Authors:

• Public Relations and Communications

• Web Team (housed in the IT department)

• Information Technology (IT): Development

• Information Technology (IT): Hardware and Network

Key “Input” Stakeholders:

• Business Unit Communication

• Business Unit Programs

Two Years Later

Two years after implementing this framework, the organization has been able to normalize the majority of the public website’s look-and-feel, and the team communicates well. The Web team has adopted an incremental approach to standards definition and implementation. A number of key standards have been documented and are supported by all internal stakeholders. The framework implementation has been effective because the organization, as a whole, now sees the value of a standards-based approach to development and perceives Web governance as an enabler, not a roadblock. The team has also come to see the value of a unified approach to Web standards.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.