Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART I

Making a Digital Governance Framework

CHAPTER 2

![]()

Your Digital Team: Where They Are and What They Do

What Is Your Digital Team?

Your Core Team

Your Distributed Digital Team

Committees, Councils, and Working Groups

Your Extended Team

Exercise: Establishing Your Field

Summary

I’m a real fan of music—any kind of music, as long as it’s got some soul to it to. But, if I had to play favorites, I’d have to say that I like symphony orchestras and small jazz ensembles the most. In my mind, they represent two ends of the musical spectrum—like the yin and yang of music. Jazz seems on the surface to be highly unstructured and free. Alternately, orchestral music has a reputation for being really prescribed and controlled. But it’s not that simple. Embedded in each of these styles of music is its inverse—so, orchestral music at its best can be wildly evocative and free, and improvisational jazz, that sounds so unformed, usually operates over a mathematical grid of tonality. Thus, the symphony has the emotional richness we associate easily with jazz music, and within jazz lies the discipline we associate with orchestral music, as shown in Figure 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and Time for Three perform at Carnegie Hall’s Spring for Music festival.

But, if you look at the interactions and artifacts required for a typical hour’s worth of quality jazz versus an hour’s worth of quality orchestral music, you’ll see a big difference. Jazz musicians might have a few lead sheets, which detail the melody of a tune and its basic harmonic framework, whereas the orchestral conductor is faced with a relatively thick score, usually marked up with further notes and cues. Jazz musicians might have a 10-minute conversation before they start their gig, but a symphony orchestra may spend an afternoon or more starting and stopping a piece, paying close attention to the tricky parts where the group might stumble over each other. And, even before the orchestra musicians get together to rehearse, various orchestral sections may get together to work through concerns related to their section, like bowing strategies for string players. It’s not an accident that all the bows in a violin section all move together!

In the end, both the jazz trio and the orchestra can deliver a powerful performance that satisfies the audience. And both groups rely on the competence and expertise of individual musicians. The difference lies in the fact that one group makes it up as they go along and sees where it takes them, while the other one doesn’t. It’s a different means to an end and that means is dictated by one thing primarily—the size of the group involved. It’s easier to get three or four people to collaborate and invent in real time than it is to get 100 people to do so.

It’s likely that your organization’s early Web team was like a jazz trio—that is, a group of highly engaged people with special skills working on one website and making things up as they went along. And it worked—for a while. Now, 15 or 20 years later, an organization might have 10, 100, or 500 people and an array of external support vendors putting in effort to support their digital presence. And, instead of websites being an interesting business oddity, they have become mission critical. Only the problem is that no one has taken the time to mature and intentionally form the digital team that supports those sites—to identify who all those resources are, where they are in the organization, what they are supposed to be doing, and how the whole team should work together as a unit. Just as there are a lot of different ensemble configurations between the small intimacy of the jazz ensemble and the top-down, highly structured orchestra, there are many different types of digital team configurations. Your job is to discover which configuration will work best for your organization so that you have an appropriate canvas upon which to execute your digital governance design work

The real work of a digital governance framework is to assign appropriate authority for digital strategy, policy, and standards decision-making to the right resources within your digital team. But, if you have no sense of where your team members are or what they do, it is almost impossible to assign digital governance authority properly. Let’s take a look at your digital team

What Is Your Digital Team?

Your digital team is the full set of resources required to keep the digital process functioning for your organization. Your digital team includes not just the core product-focused teams found in marketing/communications and IT, but also the casual content contributors, business unit Web managers, supporting software vendors, and organizational agencies of record. Your digital team also includes those who administer and support digital efforts by tending to the programmatic aspects of the digital team, such as budget digital team resource development and management.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Worry too much about whether your core digital team is in marketing, communications, or IT (or anywhere else in your organization). Clearly defined roles and authority are much more important than the organizational placement of your core team.

Unfortunately, many organizations identify their digital teams as only the hands-on resources that design, write, and post Web content and create applications on a daily basis. This narrow view of the digital team reinforces the idea that digital is a tactical function and not a strategic one that requires planning and resource management. It also minimizes the deep information and technical architectural issues that must be addressed in order to do digital well and safely for your organization and your users. With a broader perspective of your digital team, it becomes clear that your team is all over your organization, and there comes the realization that there is a diversity of skills required to support digital. Some of those skills existed in your organization prior to digital, and some of the skills are new. Some skills are specifically related to digital expertise, and some of them are related to other domains.

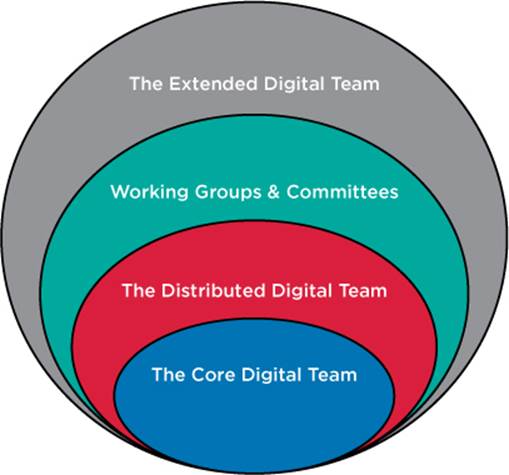

An easy way to get a handle on your digital team is to consider the following (see Figure 2.2):

• The location, role, and budgeting source of your core digital team.

• The location, roles, and budgeting source for your distributed digital team, which can include departmental Web managers, country Web managers, product-focused content contributors, and other satellite teams.

• The authority, role, and budgeting source of any digital steering committees, councils, and working groups.

• The identity of and budgeting source for your extended digital team, which includes agencies of record, software integrators, and other external vendor support.

FIGURE 2.2

Components of your digital team.

Once these aspects are clearly understood, you will have established a clear resource field upon which to place decision-making authority. Now, let’s look at each aspect of your team in more depth.

NOTE LIKE MAKES LIKE

Well-organized, effective digital teams usually produce a well-organized and effective digital presence. Conversely, a poorly organized, inefficient digital team usually produces a poorly organized and ineffective digital presence. The main product of digital team disorganization is redundancy of effort, which can lead to things like a bad user experience through conflicting interface and application design standards, or fiscal waste through the implementation of duplicitous back-end systems.

Your Core Team

The core digital team’s job is to conceptualize, architect, and oversee the full organizational digital presence. In most organizations, the core digital team is the set of resources you most likely called the “Web team.” In an environment where digital governance is immature, this team often has de facto authority over digital standards—that is, until a powerful stakeholder disagrees with them. Often, they are in either marketing/communications or your IT department. But technically speaking, the team can be anywhere in the organization. The core team has many responsibilities that can be distilled into two functions: program management and product management.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Try to run your 100-person digital operation as a loose collaboration. Make sure that roles and responsibilities are well defined and that you have bridging functions cutting across working silos.

Core Team Program Management

NOTE PROGRAM MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITIES

• Oversees local and global digital staff and budget.

• Implements digital strategy.

• Measures and reports on the effectiveness of digital initiatives

• Informs and authors digital policy.

• Builds and sustains internal digital community of practice.

Program management is the administrative side of digital. Its function is to enable the digital process by ensuring that the digital team is properly resourced, which includes the management of staff, vendors, and capital expenditures. The program management function also oversees the tactical evaluation of the digital team and digital platform performance, in essence measuring how effectively they have implemented the organization’s digital strategy.

Core digital team program management resources are an important and often missing link between hands-on digital workers and the rest of the organization. Program management resources offer jargon-free, quantitative and qualitative evidence to leadership in order to garner fiscal and strategic support for the growing resource needs of the digital team. Unfortunately, many organizations have a weak digital program management function. For some, tactics for the measurement of digital performance are elementary with a focus on website page hits and social media “likes” instead of on things like related fiscal business performance and user experience metrics. Usually, no one in the organization has a clear understanding of what is being invested in digital. Often, digital efforts are sustained by the non-strategic leaching of human and fiscal resources fromcommunications and IT budgets. A result of that is an often siloed approach to digital development. In many organizations, resources can be found for initiatives that center on communications or IT-focused tasks like content creation, visual identity, and systems platforms and application development, but the more obscure but essential digital functions like taxonomy, component content modeling, user experience, and digital analytics development are left without support. A mature approach to program management would address the full scope of digital and ensure that staffing and budgeting are adequate for all areas.

Ideally, an organization’s core digital program management function would be staffed by individuals who have a firm understanding of the capacity and capabilities of digital and who also have management expertise. In many organizations, the program management function is filled by the Chief Marketing Officer or a senior marketing manager. In organizations that have a stand-alone digital team with communications, digital, and IT resources, this role could be filled by a director or vice president of digital. Or, if much of the core team function resides in the IT department, this program management function could rest with the office of the CIO or some other senior IT manager.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Consider the make-up of your entire digital team. That includes not just hands-on resources but also business stakeholders who have a vested interest in the effectiveness of your organization’s online efforts. They have a role to play as well.

Unfortunately, digital program management responsibilities are sometimes minimized or dismissed by digital leads that come from a hands-on digital development background. They focus the core digital team on production, possibly jumping in and playing a hands-on role themselves, while pushing aside practical management tasks. The result of this hyper-focus on production means that the digital team staff often suffers from a lack of professional development. Many Web managers and digital directors have only worked in digital and are unaware of tried-and-true human resource management tactics that could support and grow their staff. To add to the confusion, the human resource staff is often locked in a pre-Web worldview of canned marketing and IT job descriptions and is not able to effectively support the appropriate resourcing of the new field of digital. In a healthy environment, human resources departments, Web managers, and digital directors work together to manage and develop the digital team staff so that they have the same sort of career growth opportunities as those in marketing, sales, or IT.

Core Team Product Management

NOTE PRODUCT MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITIES

• Supervises product development and maintenance.

• Assists in Web development of community support and training.

• Gathers digital metrics.

• Informs digital policy.

• Defines digital standards.

• Implements and supports core infrastructure technologies.

• Develops and maintains the organization’s “corporate” or top-level website.

The core team’s product management arm is responsible for ensuring that the organization’s entire digital system works coherently on many different levels. That includes technology platforms and content strategy, but also the “meta” aspects of development that give digital its power, like information architecture and taxonomy. This diversity of mission means that the core digital product management team serves as a digital domain expert, a service provider, an integrator, and a business analyst—all at the same time.

The product management arm of the core team is often responsible for defining digital standards and providing domain expertise in the definition of policy. They are also responsible for implementing strategies and technologies to support the measurement of digital effectiveness. Resources on this team help define the specific metrics and implement the processes and technologies for digital effectiveness measurement. They are also responsible for ensuring that shared aspects of digital are effectively managed and that other people in the organization who need to use those systems are properly trained to do so. That means that things like Web content management systems, analytics software, search engine software, ecommerce engines, and marketing automation software are often implemented and supported by this core team.

In practice, the core team is responsible for the tactical management of an organization’s core digital presence, such as the main organizational website or the top-level pages of that site. See the “Core Team Roles” for a better understanding of the potential members of the core team.

NOTE CORE TEAM ROLES

• Application developers

• Content strategist

• Data analysts

• Developers

• Editors

• Graphic designers

• Information architects

• Librarians

• Producers

• Program managers

• Project managers

• Records managers

• Scrum manager

• Social media moderators

• Systems administrators

• Technologists

• Trainers

• Translators

• User experience specialists

• Videographers

• Writers

Should the Core Digital Team Be in Marketing or IT?

This is my most frequently asked question. There are usually two dynamics behind the question. The first is the desire to resolve a power struggle between certain organizational factions. The second dynamic is an assumption that there is an absolutely ideal structure and ideal home for all digital teams. That’s not really the case. Good digital team design is always relative to a variety of factors, including how an organization budgets for digital, the geography of digital resources, and an array of other factors I’ll discuss in Chapter 6, “Five Digital Governance Design Factors.”

It doesn’t matter if the core team is in marketing/communications/PR or a more technically focused team, like IT or IS. Either will work if roles, responsibilities, and funding are clear—and the team is complete. “Complete” means that all the resources required to support the development of digital are on the same team and reporting to the same manager. Often, companies will have split teams, meaning that all the design and editorial aspects are being dealt with by the communications or marketing team, and the application design and network and server infrastructure work is being handled by IT.

Keeping the Core Whole

Because of the core team’s foundational role, ideally, it should not be scattered across multiple aspects of the organization. But, in practice, this is often not the case. In many organizations, the core digital team is bifurcated—with one main branch in the IT department and the other main branch in marketing, communications, or public relations. The reasons for this common split are obvious: a digital presence is a content-rich communications-focused series of channels that exist on a technology platform. Sometimes, in organizations with a transactional focus, the split can be two- or three-fold with other key stakeholder’s organizations playing a strong core role.

Organizations should make an effort to overcome these legacy patterns and integrate digital resources on one team. Collaboration models where teams are distributed across the organizations and reporting to multiple managers can work, but for the core, it’s especially important to foster close, spontaneous, and inventive collaboration—like that of the jazz ensemble—and this is best served when resources are co-located.

The Dispersed Core

If you work in a large organization or an organization that has vastly different product or business interests, the responsibilities of the core team may need to be dispersed. In these instances, multiple cores take on the same program and product management responsibilities as the corporate core team but for only a particular aspect of the digital presence, like an area of the organizational website or a brand-focused site or microsite.

For instance, in a holding company that has multiple brands and multiple websites, the core digital team’s standards decision-making may be minimal with the bulk being delegated to individual brands or businesses. Sometimes, this delegation of authority can be so complete that the brand- or program-focused teams have complete authority over all the content, applications, and back-end systems that support digital. Another rationale for distributing core team functions might be localization requirements. While digital content is often translated from one language to another, sometimes digital products and services must be more deeply localized to align with business and cultural norms.

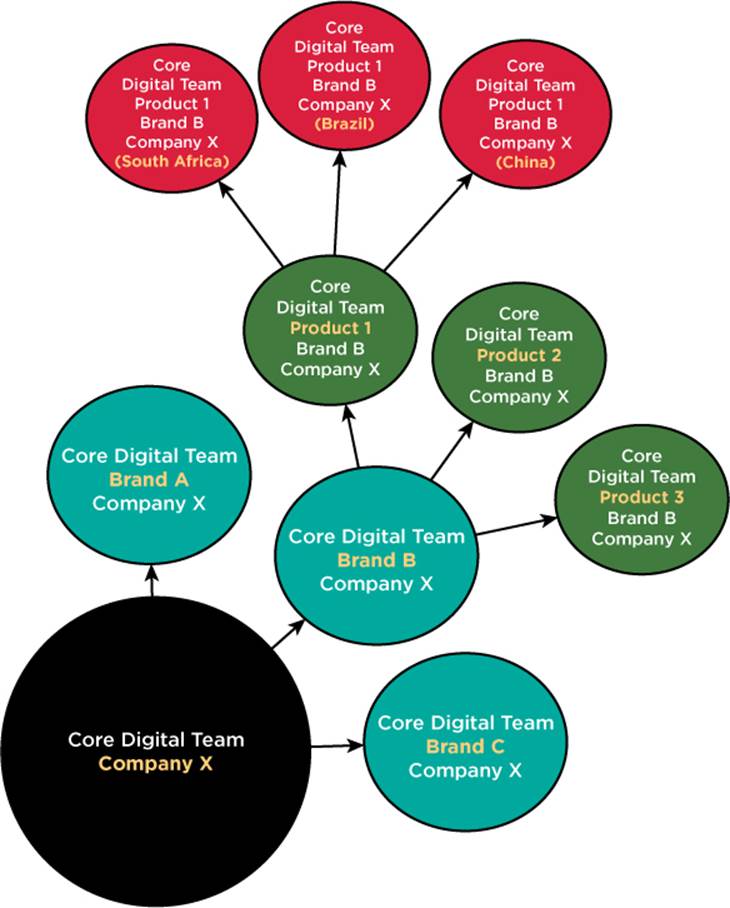

Often, in these deeply dispersed models, various brands, products, and programs have developed their own local digital governance concerns. For example, a product line that has been given authority to develop standards for its own product might delegate standards development authority to different geographical regions. When practices like these begin to emerge, the organization begins to develop a governance structure that resembles a network array with nodes of authority delegated from the core to brands, programs, or product lines of the organization (see Figure 2.3).

FIGURE 2.3

The dispersed core team.

This model, if well-designed, can be very powerful because it allows the top-level organization to dictate policy and standards in the areas where uniformity makes sense, while at the same time allowing brands and locales to have their own digital policy and standards as required to maximize business effectiveness.

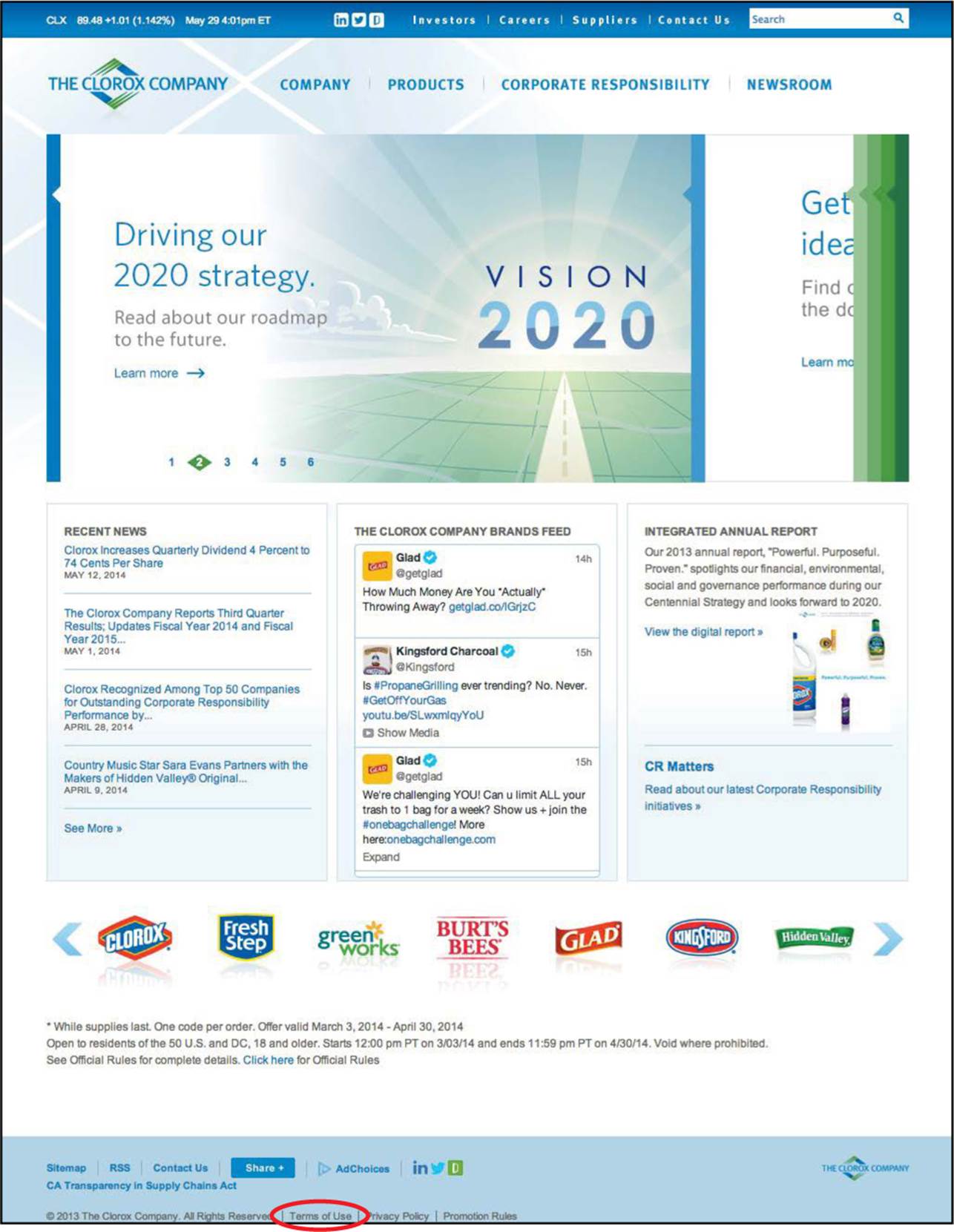

The Clorox Company is an example of an organization where the vast majority of digital standards definitions (and corporate brand standards in general) might need to be delegated from the corporate core into specific brands. At the same time, some policy definition authority is still held at the Clorox corporate level (see Figure 2.4). Despite the variety of brands held by the Clorox Company, in the United States, most brands link back to the Clorox corporate site for their “Terms of Use” (see Figure 2.5). And a small amount of clicking around the Clorox Corporation brand-based website globally illustrates a complex array of digital standards and policies likely influenced by a difference in product offering and regional World Wide Web policy considerations.

FIGURE 2.4

The Clorox Company references its “Terms of Use” at the bottom of its page.

FIGURE 2.5

The Clorox Company’s “Terms of Use” for United States websites.

Your Distributed Digital Team

NOTE DISTRIBUTED DIGITAL TEAM RESPONSIBILITIES

• Maintains the quality of a particular aspect of the digital presence.

• Develops and maintains content, applications, or data to support the digital presence.

• Provides input for the development of digital standards.

Once core standards and infrastructure systems are defined and implemented, a digital presence needs to be developed, supported, maintained, enhanced, and moderated. In large organizations, this is the responsibility of the distributed digital team. Using defined policy and standards as guidance, the distributed team extends and focuses the vision of the core team by implementing content and applications that map to specific business concerns.

In organizations with a relatively unsophisticated digital presence, the core team might oversee the maintenance and development of an aspect of the digital site like the main corporate website or top-level pages, but in an ideal model, the bulk of production and development should happen outside of the core. That model might mean product lines for business, admissions, and registrar’s offices for universities, and membership and publications for non-profit organizations. This distribution makes sense because, while the core team may know best how its new functionality and content might fit into the overall organizational digital ecosystem, they can’t be domain and knowledge experts regarding every aspect of the business. In organizations where digital governance is immature, distributing production among resources without a solid standards framework (and the authority to enforce it) will almost inevitably lead to a disintegrated user experience.

The scope of the day-to-day activities of the distributed team can be small or large. The responsibilities might include posting press releases on the public website or updating lunch menus on the intranet. Or your distributed team could implement applications and deploy new websites. The key point, as you’ll see Chapter 5, “Stopping the Infighting about Digital Standards,” is to put in place the authority for the standards definition. In most instances, the majority of that authority will lie within your core digital team, but sometimes that authority is passed on to the distributed Web team. For instance, authority for editorial standards might be delegated to the corporate entity that uses plain language standards, but other aspects of the organization that serve special audiences might allow a more specialized vocabulary for its user base. The important governance factor isn’t where the work is being executed, but rather where the authority for the standards that control the outcome resides.

That designated authority doesn’t mean that the members of the distributed digital team do not have a voice in the development of the standards they must comply with. You’ll see in the standards chapter that they play a vital role in providing input for standards.

Committees, Councils, and Working Groups

NOTE THE ROLE OF COMMITTEES, COUNCILS, AND WORKING GROUPS

• Vets and approves guiding principles.

• Discusses high-level business metrics.

• Examines how digital should be resourced.

• Brainstorms new ideas or technologies.

An organization’s digital presence represents an entire organization, so it only makes sense that cross-team collaboration and discussion will occur when developing and maintaining Web and mobile sites and moderating social channels. But sometimes organizations will have to form temporary and permanent working groups or committees to address certain digital concerns.

When these teams have a clear goal and mission, these committees, working groups, and councils can add real value to the organizational digital team. Production-focused “hands-on” groups make a great environment for digital standards decision makers to get input from stakeholders, and executive level steering committees are the natural home for vetting and approving guiding principles, discussing high-level business metrics, and having the tough conversations about how digital is resourced in the organization. Just make sure that you don’t think these groups will take the place of a well-designed digital governance framework. Because they won’t.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Make sure that your working groups and committees are not substitutes for a real governance framework. Cross-functional working groups are wonderful for fostering collaboration, but sometimes they fail when it comes to establishing and enforcing standards.

The Decentralized Digital Government

FIGURE 2.6

The FDA website circa 2007.

One of the early governance projects I worked on was with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA, like many governmental agencies, leveraged the Web early in order to surface important information and data to citizens and specialized professionals. Within the FDA were multiple centers and to a certain degree, they all marched to their own drummer online. This resulted in a variety of different graphic designs online, sometimes making it unclear to users whether they were on an FDA site or somewhere else in the government (see Figure 2.6). Before executing the redesign, though, leadership took the extra steps necessary to establish a governing framework and established senior management level and executive level governing and working groups. The result was that the organization was able to move smoothly to a new integrated website design. Since then, the FDA has iterated on the design and functionality of its online presence, as shown in Figure 2.7.

FIGURE 2.7

The evolution of the FDA website.

Who Are the “Bridges?”

Bridging resources are facilitators with no governing authority. Their job is to navigate horizontally and vertically within an organization in order to ensure production and goal alignment. Common bridge job titles are:

|

• Producers |

• Project managers |

|

• Scrum managers |

• User experience experts |

Bridges are patient negotiators who know your business, know digital, and can respect a deadline. In traditional organizations, these might be project managers. In interactive agencies, these could be producers. In an agile environment, they might be scrum managers. Whatever the name, the role of the bridge is vital. They are the “glue” between the requirements set or expected business outcome and the people who are getting the work done. Those people working in the bridging function move around a lot, and they go to a lot of meetings. They negotiate. As a group, they play the role of digital portfolio managers helping to prioritize projects and work for the organization. They interact with business stakeholders, developers, vendors—whomever they need to in order to get the job done.

In its essence, though, the bridging function provides two clear outcomes. First, it keeps the product management team focused on the business outcome, which means making sure that the functionality, system, and content meet the business need, and that the project is delivered on time and within budget. Second, the bridges also keep the project business owner from bloating requirements (“scope creep”) and from micromanaging and overburdening artisan production resources so that these resources can do their work quickly and efficiently.

Organizations are notorious for not staffing this bridging function well. In many cases, artisan production resources are expected to do both the work and manage their internal “clients.” This scenario is usually unproductive and can lead to bad situations where skilled digital resources spend most of their time in meetings and are forced to do their “real” job like developing code, designing, or writing content after hours or on weekends. And often, skilled digital artisans are not the best bridges. Traits like being hyper-focused and uncompromising, which might serve an application developer well, have a not-so-positive impact when the bearer attempts to function as a bridge. In many cases, the poor use of an artisan has led to conflict and staff fatigue. Sometimes, skilled and desirable resources move from one job to the next in search of relief when, in reality, the organization’s expectations were simply unreasonable. In these cases, important information about the operations of the organizational digital platform leave with the resource, particularly in an environment where there are a lot of “homegrown” digital applications and systems that are largely undocumented.

Often, an organization’s first attempt to address digital governance concerns is to create a governance-focused working group, council, or steering committee. More often than not, these groups are not able to effect the changes required in the organization, because they don’t have any real authority. Pulling together a group of hands-on digital managers is a good idea if you want to brainstorm standards, educate, collaborate, or discuss best practices. However, a group of low-level managers usually doesn’t have the authority to shift headcount or change an organizational budget. Alternately, executives who come together in a governance steering committee to approve digital projects usually don’t have the digital expertise to make good decisions.

Your Extended Team

Because of the speed of change around digital, organizations are hard pressed to staff their teams with all the relevant skill sets, so leveraging external development and production expertise can make a lot of sense—particularly from a human and fiscal resource perspective. You should consider if it might make sense for your organization to utilize external vendor support. That support could range from simple overflow production support for a momentarily overtaxed internal digital team to the complete outsourcing of digital. Understanding who your external vendors are and how they support your core and distributed digital teams is important. Often, organizations have an array of vendors in place—sometimes working at cross-purposes. In these cases, the vendors are usually the last ones to tell the organization that their redundant services are not really needed, or worse, are not contributing to a higher quality experience for their users. You should have a firm understanding of which external vendors support your digital presence, what they do, and how much you are paying for their services. This list can include interactive agencies, as well as website hosting vendors, management and analytics consultants, software as a service vendors, systems integrators, and so on.

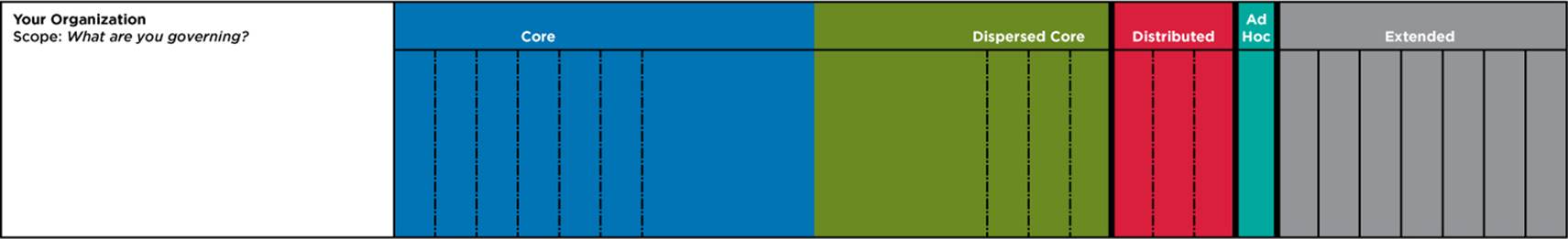

FIGURE 2.8

Your beginning digital governance framework fill-in-the-blanks.

Exercise: Establishing Your Field

Who is governing? Digital governance frameworks are organizational concerns (see Figure 2.8).

1. First, identify the organization that is delegating authority. It could be your top-level organization, or a branch, department, or some other organizational subdivision. Remember, if you are part of an organizational subdivision, it is import to ensure that you have the authority to delegate certain responsibilities. All authority is held at the core of the organization and then systematically delegated outward.

2. Describe the scope of your framework. Governance frameworks apply to a set of digital products and services, so it’s important to be clear about what you are governing. Is it for all of your organization’s websites, mobile applications, and social channels, or is it just your top-level site? If you have multiple digital properties and immature governance, even answering this question may take some conversation among stakeholders, particularly if there are websites and applications that the core team might feel are “rogue” or unsanctioned.

3. Identify the organizational components that function as your core, dispersed core (if any), distributed, ad hoc, and extended digital team members. At this point, just take a best guess. As you work through the rest of the book and examine strategy, policy, and standards decision-making authority in more detail, you may find that you need to make some adjustments. This is okay and normal.

Now that your field is outlined, you’re ready to start allocating authority for decision making for digital strategy, policy, and standards.

SOFTWARE SELECTION AND GOVERNANCE

Alan Pelz-Sharpe, 451 Group

All too often, folks buy IT systems to solve a problem without fully understanding what the problem is in the first place. A proactive, up-front approach to digital governance provides an insight into what’s really going on, and most importantly, provides a level of control that frankly is usually lacking in organizations. Buying software first, installing it, and then considering digital governance in retrospect will ensure more work and a much higher risk of failure.

Summary

• Your digital team includes the full spectrum of resources required to manage your digital presence. The team has four components: a core team; a distributed team; committees and working groups; and the extended team.

• The core team is responsible for defining and implementing the core digital platform and for establishing the standards that the entire team must adhere to.

• The distributed team is responsible for producing and maintaining an aspect of the digital presence. They bring business domain expertise or specialized knowledge to the digital presence.

• Committees, councils, and working groups add value by bringing together otherwise functionally silo’d resources in order to achieve a specific digital goal or to provide organization-wide oversight of digital efforts.

• The extended digital team includes non-employee resources that support your digital presence. This includes resources like website hosting service providers, interactive agencies, and technology implementation partners.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.