Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART I

Making a Digital Governance Framework

CHAPTER 3

![]()

Digital Strategy: Aligning Expertise and Authority

The Organizational Response to Digital

Who Should Define Digital Strategy?

Do You Really Need a Separate Digital Strategy?

Is Your Leader a Digital Conservative or a Digital Progressive?

Summary

I take the train a lot from Baltimore to New York City. I’m not much of a train talker, but occasionally I will strike up a conversation with someone sitting near me at the end of my journey (see Figure 3.1).

FIGURE 3.1

You can have some fascinating discussions en route.

Once, in the midst of an early evening approach to Penn station, New York, I started a conversation with a gentleman sharing my table in the café car. It was right around the time that Blockbuster (the global video brand) filed for bankruptcy and Netflix was starting to look super-savvy and invincible. The gentlemen had a Wall Street Journal, and I pointed to the Blockbuster story and said something like “Leadership sure dropped the ball on that one.”

He put down his paper, looked at me over his glasses, and asked me what I did for a living. I told him, and he wrinkled his brow. (Okay, I don’t have a normal job.)

“Have you ever heard of Clayton Christensen’s concept of disruptive innovation?” He quizzed, taking on a teacher-like tone.

Of course.

“Well, he said, “When these sorts of disruptions happen, it’s no one’s fault. No one can see it coming. It’s like a bomb dropping out of nowhere.” Wall Street Journal back up in front of his face.

“Well,” I said to the newspaper. “That would be true if this were the mid 1990s. But Netflix has been around for a while now, and Blockbuster must have noticed they were losing market share, right? So this was like a bomb you could see coming for 10 years.”

No reaction. I continued.

“But I see this all the time in business. For whatever reason, management doesn’t want to pay attention to obvious indicators. You know, there’s a sort of managerial hubris that develops in successful organizations—where they somehow think they can’t fail. Or they think they are entitled to majority market share, just because they’ve held it for so long.”

Okay, so maybe I didn’t say those exact words, but I did say something like it.

Paper down. “Managerial hubris?”

Oops.

The conversation went on a bit back and forth, and by the time we’d crossed under the Hudson and were getting off the train, it was clear that he and I were of two differing opinions. As an “executive at a publishing company,” he felt that Blockbuster leadership had been blind-sided by the World Wide Web and “predatory” companies like Netflix, Redbox, and Amazon. I felt that executives should have seen the shifts in distribution channels coming a mile away and shifted their strategy to reflect the emerging new normal.

It didn’t help our brief relationship that I also went on (I’d had one of those little mini bottles of wine) about the lack of deep and informed reaction to the World Wide Web in the publishing and media industry in general.

“So...” I asked, in parting, as we rode the escalator up into Pennsylvania Station. “Blockbuster leaders couldn’t have made better choices?”

“Sure, here and there,” he said emphatically. “But no one knows how all this technical stuff works. We’re at the mercy of a bunch of kids fiddling around with our markets and changing all the rules.”

And then he was gone.

The Organizational Response to Digital

In many instances, and in many different markets, senior leaders don’t consider digital matters to be of strategic importance. For example, when I talk about digital to executives and their direct reports, they refer to websites, mobile channels, and social media as “technical stuff.” Some leaders dismiss digital by saying, “I have staff that handles that.” When asked about their digital budgets or performance measures, they often have no real answer. “I don’t know,” they say. “They tell me we get a lot of hits.” Sometimes, if I strike up a real rapport with an executive, he might confide that he is completely confused or intimidated by this new platform—one that didn’t exist when he built his career. How can he manage what he can’t understand?

NOTE DIGITAL STRATEGY DEFINITION

A digital strategy articulates an organization’s approach to leveraging the capabilities of the Internet and the World Wide Web. A digital strategy has two facets: guiding principles and performance objectives.

If interest in digital does exist, it might only be around the visual aspects of digital—the things they can see. Executives might think a competitor’s website looks better, or they might covet a mobile app that they’ve downloaded on their smart phones. Occasionally, I’ll get a leader who is a digital zealot. That opinion can manifest itself in a number of different ways, from a sensible well-supported digital strategy and execution plan (best) to random mandates to implement the functionality or application of the year (worst). (See “Is Your Leader a Digital Conservative or a Digital Progressive?” later in the chapter.)

Meanwhile, in the trenches, the digital team is often at a loss as to how to effectively make a strategic case for digital to executives. Maybe they’ve been trying for 10 to 15 years to get executives to fund their efforts and take digital seriously with varying degrees of success. The team has lobbied for big-ticket Web content management systems, search engines, and other software tools and asked for specialized headcount for things called information architecture, Web analytics, and user experience. When the Web teams are asked about leadership’s role in digital, they might say that their executives are “ignorant” of the Web, old fashioned,” “pre-digital,” or “think that websites build themselves.” These directors of digital, Web managers, and user experience experts usually say this with some disdain, because they feel that anyone who leads business in the 21st century ought to understand digital. Some even feel that “legacy” leadership needs to step aside and let the digital experts run the whole show.

This extreme dichotomy represents digital in a way that often resonates with digital workers: the digital team as a group of helpless marionettes dancing at the whim of a digitally clueless executive puppeteer. “This is why we can’t develop a real digital strategy.” But it’s really not that simple.

Yes, there are a lot of executives who need to understand the impact of digital better, but some of an organization’s inability to define and execute an effective digital strategy stems from the digital worker’s lack of basic management skills. While senior leaders may have grown their careers in a pre-Web environment, leaving them less than Web-savvy, many digital workers have experienced their entire professional career in the rarified air of a corporate Web team. It’s an environment that is often undervalued and understaffed, but one that also has a history of operating without clear performance objectives and accountability to the business.

Because digital teams are often led by managers who don’t understand how digital works, digital resources may not have been developed as well as their counterparts in pure marketing or IT roles. So, even though the people may have worked in an organization for 10+ years and have tremendous responsibilities, they might not know how to write a budget, make a business case, negotiate with colleagues, or seek and offer mentorship. And it is these skills that are required in order to mature and integrate digital with the rest of the business.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Make sure that your digital strategy is articulated via both quantitative and qualitative factors.

Luckily, senior managers and executive usually do have these skills in abundance. One of the benefits of properly identifying the resources that will define the organizational digital strategy is that there will, hopefully, be an intermingling of those people with institutional knowledge and business savvy and those with digital expertise—senior leaders and digital experts sitting in the same room having a serious conversation about how to get digital done in their organization. Hopefully, while the conversation is happening, some knowledge and skill transfer can take place.

Who Should Define Digital Strategy?

In Chapter 1, “The Basics of Digital Governance,” you learned that a digital strategy team ought to have three types of people resources.

• People who know how to analyze and evaluate the impact of digital in your marketspace.

• People who have the knowledge and ability to conceive and design an informed and organizationally beneficial response to that impact.

• People who have the business expertise and authority to ensure that the digital vision is effectively implemented.

Usually, all three of these skill sets can be addressed if you put performance-focused leadership in the same room with your seniormost, “forest view” digital workers and user experience experts. Each of these resources has different skills and perspectives to add to the mix.

NOTE THE ROLE OF LEADERSHIP

A good leader should manage the following areas:

• Make sure that the digital strategy is informed by non-digital strategic business objectives.

• Ensure that the digital presence performs for the organization by pressing for and contributing to the definition of measureable outcomes.

• Provide market analysis and expertise, ensuring that the digital strategy is “worth the effort.”

• Align management for implementation of the digital strategy.

NOTE THE ROLE OF THE DIGITAL WORKER

The digital worker/user experience role should perform as follows:

• Brainstorm and invent digital functionality in order to meet business goals.

• Ensure that the digital presence aligns with good practices and relevant emerging trends in digital.

• Provide digital expertise and experience ensuring that the digital strategy is “doable.”

• Ensure that the digital and non-digital experiences of the customer/user make sense and produce value for the business.

• Align organizational digital workers for implementation of the digital strategy.

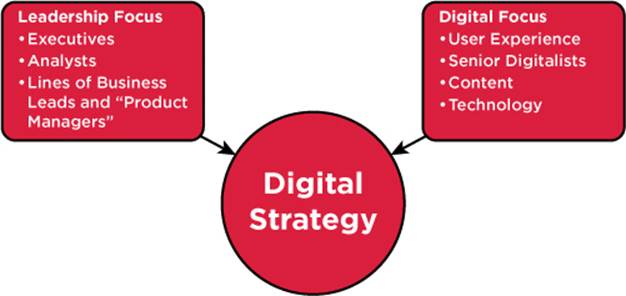

Remember, the product of a digital strategy development is a statement of the organization’s approach to digital and the development of performance measures—not a tactical plan. A digital strategy gets handed off to your team of digital leadership and stakeholders and workers (middle management and digital practitioners), who will figure out the best way to achieve those objectives (see Figure 3.2). So you don’t have to fill the room with your whole Web team and every manager who has a stake in the digital strategy.

FIGURE 3.2

Digital strategy inputs.

In fact, if you include resources who know too much about how to execute on digital or feel too strongly about a single aspect of the business, a strategic conversation can quickly get bogged down in the tactics of how many websites, mobile apps, and social channels there are and what they’ll do, or how to correct and fix the mess that you currently have online. Your team will be able to figure that out easily, once the strategy team defines what objectives the organization is trying to achieve online and once your digital governance framework clearly defines the roles and responsibilities for execution.

If your organization has a very small digital team, then your Web manager might be the only digital expert in the house. If this is the case, it’s important for that person to take off his execution cap and focus on the strategic aspects of digital for the organization. In some cases, organizations may have no in-house strategic digital expertise. Perhaps they have outsourced all of digital to an external vendor. While this is sometimes an intentional move, it is more often a reactionary maneuver by leadership that doesn’t want to deal with staffing for digital. While there are definite advantages to outsourcing certain aspects of digital, digital strategy isn’t one of them. Even if your digital strategy team is populated with some external vendor experts, make sure that it is led and “owned” by the organization. If you don’t have a resource that can do that, then hire it. It’s a deficit you can’t afford.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Confuse your organizational digital strategy with your content, technology, or user experience strategies.

Do You Really Need a Separate Digital Strategy?

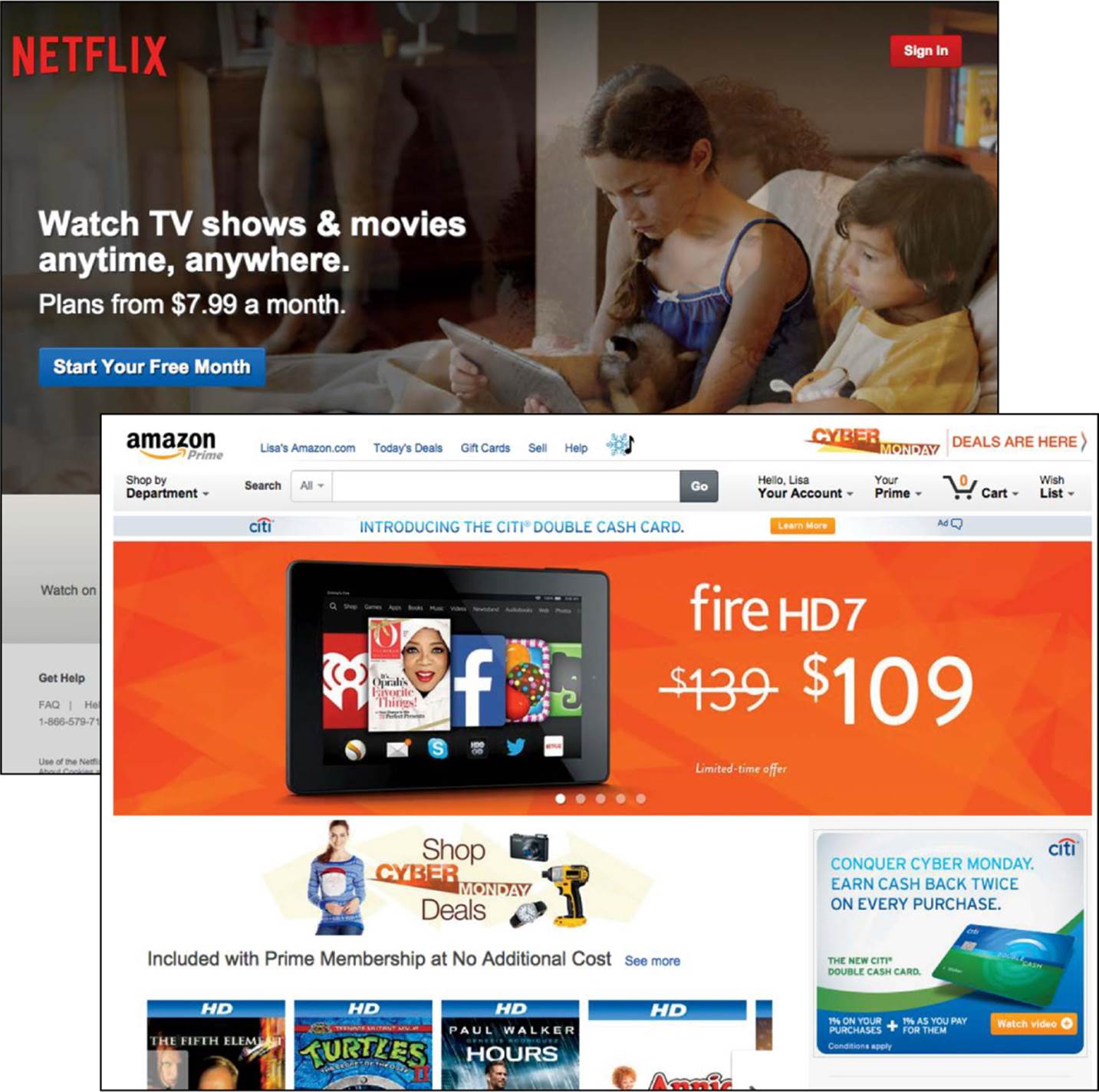

Sometimes a digital strategy might be so close to your organization’s overall strategy that it might not be articulated separately. For instance, often digital is the product or service (think Amazon or Netflix). Then there are heavily impacted industries, like traditional print publishing and entertainment—ones that have already shifted or are shifting to an all or near-all digital product delivery model. In these cases, old paradigms have broken down, and there is an active business battle happening—the outcome of which will determine the new normal (see Figure 3.3).

If you work in one of these marketspaces, you’re reeling right now. But you have also been given a gift, in a sense. Competition and the market have forced your organization to address digital strategy head-on. So, if you are someone whose job it is to manage digital in your organization, your job is dynamic and interesting. Hopefully, your organization has clarified whose role it is to define the strategy—most likely a diverse team that includes senior digital subject matter experts and business experts. In the best of cases, the organization has blended the legacy business strategy and operations with digital efforts so that everything works in concert.

FIGURE 3.3

The old business models are changing and new ones have surfaced.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Make sure that business experts and digital experts inform your digital strategy. Alone, neither of these resource types has enough knowledge to get the job done well.

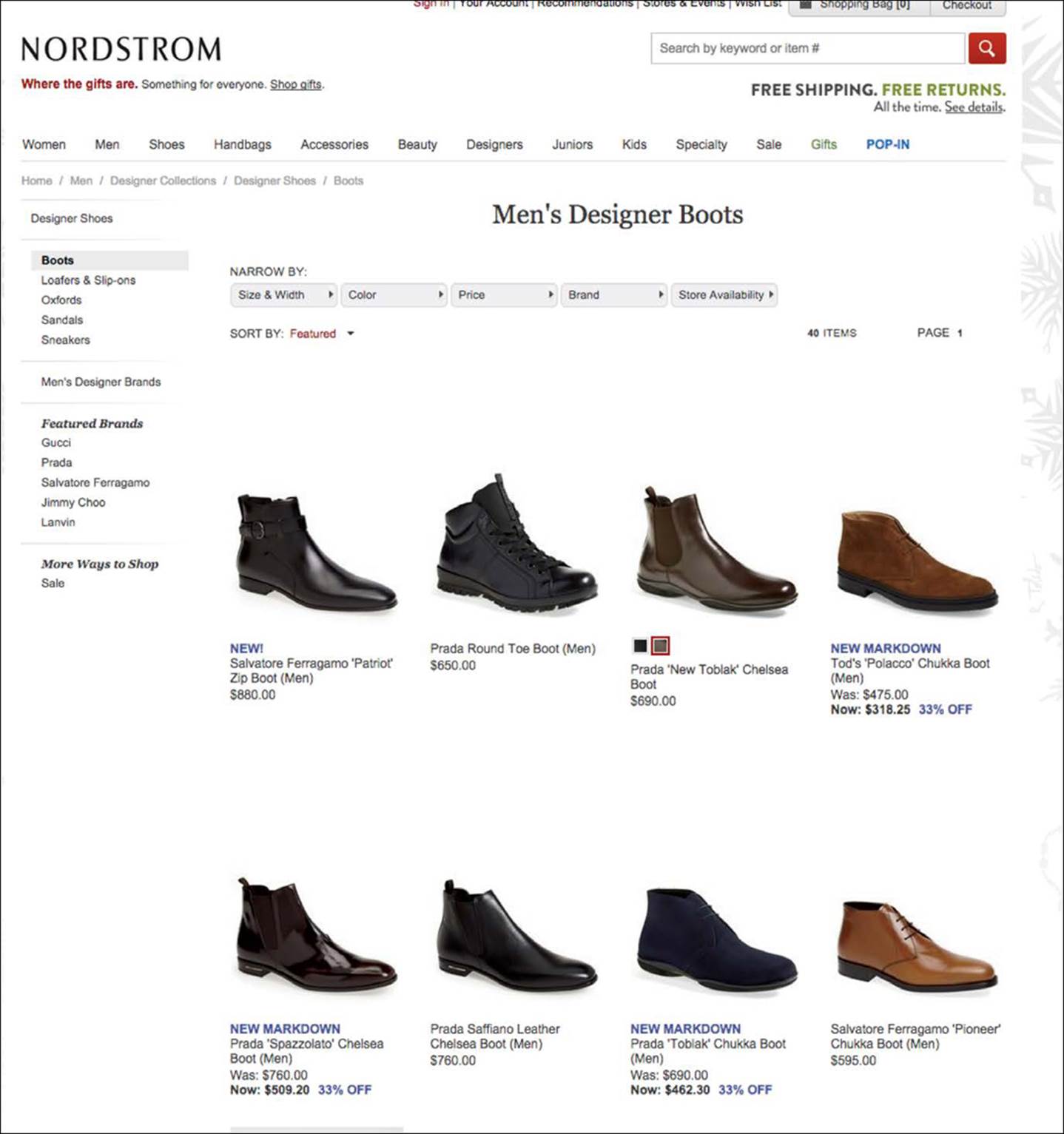

The one-two punch of digital expertise and business acumen is a powerful combination, and when a digital strategy is defined with the combined knowledge of digital capabilities and business and market knowledge, a lot of profitable innovation can occur. For example, consider the way that Nordstrom reinvented its Web-based technology to surface inventory in all of its stores to customers shopping on the Web (see Figure 3.4). By doing so, Nordstrom relieved the company of inventory that in a pre-Web environment might have been left unsold, and yet, they also satisfied the customer’s need in a single transaction. It took knowledge from both the pre-Web business experts and Web technologist to get this work done.

FIGURE 3.4

Nordstrom uses the Web to its best advantage.

What about organizations that have more subtly or ambiguously been disrupted by digital? What if you manufacture and distribute thermostat parts? What if you make ice cream? Often, conversations about digital center on businesses that have been heavily and publically disrupted—the obvious cases. So how do you determine your digital strategy when you are not forced to do so in order to remain viable or if the impact is more subtle? What happens if you see digital coming, but you just don’t know exactly how it’s going to impact your marketspace? Or what if most of what you do online happens behind your firewall on your intranet?

Interestingly, the majority of those businesses that I work with that have some of the most challenging governance concerns have not yet realized a real negative fiscal impact because of digital. They know that digital is there, but they haven’t been forced by revenue to look holistically at their organizations and re-engineer them from the core because of digital. For instance, businesses in the pharmaceutical industry often have many, many product-focused websites of not the best (read “low”) quality and some extreme governance concerns, but from a revenue perspective, these companies are some of the most profitable in the world and are doing very well. Sometimes the digital team in environments such as these ask me why their digital strategy isn’t given more prominence. If digital strategy and business strategy are such close relations, they ask, why don’t we just follow the lead of more heavily disrupted businesses and integrate digital strategy with the existing business strategy?

To be clear, I do believe that the integration of digital and “analog” business processes needs to happen, but in some cases that integration can be managed more gently. This is sometimes frustrating to those who work in digital for two reasons. First, digital experts often want to do some cutting-edge work, and sometimes they might be working in an organization that doesn’t need to be that cutting edge about digital (at least at the moment). In that case, the individuals might want to consider whether or not that organization is a good vocational fit for them. Second, often organizations use the reality that their vital business systems were not disrupted by the Web as an excuse not to manage or govern digital at all. That’s not good either. Every organization has a responsibility to ensure that their digital applications, website, and social channels are of good quality, represent their brand well, and are operating within the bounds of the law. And the first step toward these goals is defining a digital strategy. Having a strategy in place means that you will be intentional about the digital face of your organization. You will also be actively measuring the complex set of variables that will help inform executives and their teams when it is time to make a strategic move—so you don’t end up like Blockbuster.

Measuring Performance in the Digital Age

Most digital workers understand Clayton Christensen’s definition of disruption as outlined in his book The Innovator’s Dilemma: The Revolutionary Book That Will Change the Way You Do Business. One of the key points Christensen makes is that leaders in marketspaces that have been disrupted often continue to use the legacy business metrics to measure their performance. Their narrow, dated view of their market might mean they overlook or discount new business indicators as they arise, particularly when it comes to digital. Digital brings to the table a mass of quantitative data available for businesses to analyze and new toolsets to gather that data.

The quickly growing field of digital analytics seeks to integrate old and new methods of data analysis. For example, it takes into consideration both traditional and well-known performance indicators, such as units sold and customer attrition and retention, but it also mines the log files of search engines, Web content management systems, and digital analytics tools for new data so that new indicators can be established. Today, organizations are talking a lot about “big data,” specifically referring to this new data and the emerging methods of analysis available to organizations to better understand and fine-tune their business tactics.

Phil Kemelor, a thought leader in digital analytics, has outlined a number of areas that should be considered when defining digital metrics.

Web and Mobile

• Visitor activity

• Content and function usage

• Site promotion and marketing

• Internal search

• Task completion

• Site usability

• External search

Social

• Fans/followers/subscribers

• Traffic (visits, impressions/views)

• Interactions (likes, comments, posts, tweets, impressions)

• Channel ad campaign cost

• Sentiment

• Share of voice

• Value (or other research-based metrics)

• Referred traffic from social to Web or Web to social

• Referred conversions (or other online successes) from social to Web

Site Quality and Performance

• Standards compliance

• Server response time

• Server availability

Is Your Leader a Digital Conservative or a Digital Progressive?

Some organizations have a hard time getting leadership actively involved as a sponsor in the digital strategy, particularly when profit margins are healthy and the business has not been directly disrupted by the rise of Internet-enabled products and services. It’s easy to attribute the apparent digital indifference of executives to digital ignorance. But, sometimes, whether an executive leans in to or leans away from digital has to do with the individual’s personal perspective on digital. As with other aspects of business, leaders often are predisposed to a conservative or progressive approach to digital.

Digital Conservatives

Digital conservatives are slower to leverage the capabilities of digital to augment existing or invent new business processes, products, and services. Sometimes digital conservatism is adopted after a leader has analyzed the impact of digital on the business and come to the conclusion that, at least for the moment, being aggressive or innovative around digital is not of strategic importance. Or, perhaps, the organization has other, more strategic priorities. Other times, digital conservatism is the result of naiveté on the part of leaders—possibly an unsupported view that digital isn’t important because it’s not in the knowledge set of leaders, or is otherwise perceived unimportant.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Expect digitally conservative leaders to eagerly adopt new technologies. Learn how to use metrics and more traditional business jargon to engage them in digital initiatives.

So it is often hard to determine which type of digitally conservative leader you might have. Those who are intentionally conservative about digital might still use traditional business metrics and tactics to evaluate their business. For example, they may notice that they are losing marketshare, but instead of stepping back and looking at the fundamentals in considering the changes that the disruption might have put on their organization, they react tactically in the same manner that they did in the predigital environment, not really understanding that the basic playing field of their business may have changed.

If a digitally conservative leader uses good management practices, intentionally delegates authority for digital strategy to more junior resources, and clearly establishes decision-making authority and organizational structure around digital development, then an organization led by a digital conservative might have a simple, small, and well-governed digital portfolio but one that is of the highest quality and very effective. If, on the other hand, a digital conservative is simply ignoring or dismissing digital without addressing the management mechanisms, the result could be and often is combating digital teams and online websites and social channels in disarray.

NOTE THE UNINTENTIONAL DIGITAL CONSERVATIVE

The unintentional digital conservative often has the following characteristics:

• Delegates digital strategy to more junior resources due to lack of interest.

• Feels threatened by digital.

• Uses traditional pre-Web business metrics and tactics to evaluate and drive their business.

• Is often unfamiliar with the strategic capabilities of digital.

NOTE THE INTENTIONAL DIGITAL CONSERVATIVE

The intentional digital conservative usually exhibits these characteristics:

• Purposely delegates digital strategy to more junior resources.

• Monitors how digital is impacting the organization.

• Incorporates new ways of measuring business effectiveness.

• Understands the strategic capabilities of digital and how it might be leveraged in the organization’s market.

Digital Progressives

Digital progressives are faster to leverage the capabilities of digital to augment existing or invent new business processes, products, and services. There are obvious digital progressives, such as leaders of organizations like MailChimp, Amazon, and the myriad of other 1990s and more recent digital start-ups—organizations that built themselves from the ground up on a digital platform. All digital—all the time. These organizations are obviously led by digital progressives. But if you look at organizations that existed prior to the advent of the commercial Web, you will see other dynamics.

In businesses that existed prior to the advent of the commercial Web, you will see two types of digitally progressive leaders. There are those out front who are reinventing their business and sometimes their vertical marketspace by maximizing the capabilities of digital. They might be leveraging “big data” to better understand the behaviors and needs of their customer base and to shape and drive the operations of the business. And you can also see the digital progressive that leans into digital indiscriminately. These people identify the latest digital technology or marketing tactic as a panacea or a quick boost onto the Internet, without paying attention to the fundamentals of real business needs and performance.

As with digital conservatism, an organization led by a digital progressive can have a positive or negative result. A progressive approach to digital with an undefined or ill-defined digital strategy and weak governance and operational practices can lead to chaos online. However, a progressive approach to digital with a clearly defined digital strategy and a clear approach to operations and governance can not only produce a great result for an organization, but it can also alter a marketspace.

NOTE THE UNINTENTIONAL DIGITAL PROGRESSIVE

The unintentional digital progressive might have these characteristics:

• Implements digital capabilities without real business case or performance objectives.

• Sometimes indiscriminately adopts new technologies without any real business purpose.

NOTE THE INTENTIONAL DIGITAL PROGRESSIVE

The intentional digital progressive often exhibits the following characteristics:

• Integrates digital strategy with overall business strategy.

• Utilizes digital capabilities to invent new ways to do business and to set norms for others in their marketspace.

• Tunes operational and governance practices to support the new normal of digital.

Whether your leader is a digital conservative or a digital progressive is not a case of “good” or “bad.” It all depends on your organization’s market and how digital is impacting that marketspace. For instance, might Blockbuster have done better with a digital progressive at the helm? Does your local plumber need to implement an application so that you can use your smart phone to make an appointment to get your sink unclogged? Does an engineering company need to capture the knowledge of its aging and retiring workforce?

These are strategic business decisions that point to the importance of a solid digital strategy informed by the knowledge and authority of digital experts and organizational leadership.

DIGITAL GOVERNANCE MATRIX

David Hobbs

Website migrations are complex and often result in a site that has the same problems that were in place before the transformation. Solid Web governance helps to define the website vision in the first place to anchor decisions in planning and executing the migration, take a longer and ongoing view of your website so the website quality doesn’t immediately degrade after launch, clarify decision making so that important goals get more attention than the squeaky wheels, and also set the processes and structures to define standards so that the newly-migrated site is more consistent and coherent than the existing site.

Summary

• Organizational leadership and organizational digital team professionals often have different ideas about how the organization should adopt digital functionality. Sometimes leaders, particularly those who built their careers prior to the advent of the commercial WWW, are slow to explore digital capabilities. And, sometimes, digital professionals want to implement new technologies without a real business case for doing so.

• Defining an effective digital strategy requires both organizational and digital domain expertise. In the best case scenario, these two sets of resource work together, and in the process, have a knowledge exchange that can strengthen the skill sets of both leaders and digital domain experts.

• Not every organization needs a distinct digital strategy. In cases where digital products and services make up the vast majority of the organization’s product and service offering, the digital strategy and business strategy can be the same thing. In instances where there is not an obvious way to leverage digital in order to benefit the organization, a separate digital strategy might be required.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.