Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART I

Making a Digital Governance Framework

CHAPTER 4

![]()

Staying on Track with Digital Policy

Finding Your Digital Policy

Policy Is Boring and Standards Aren’t

Policy Attributes

Identifying a Policy Steward

Assigning Policy Authorship Responsibilities

Writing Digital Policy

Raising Awareness About Digital Policy

Summary

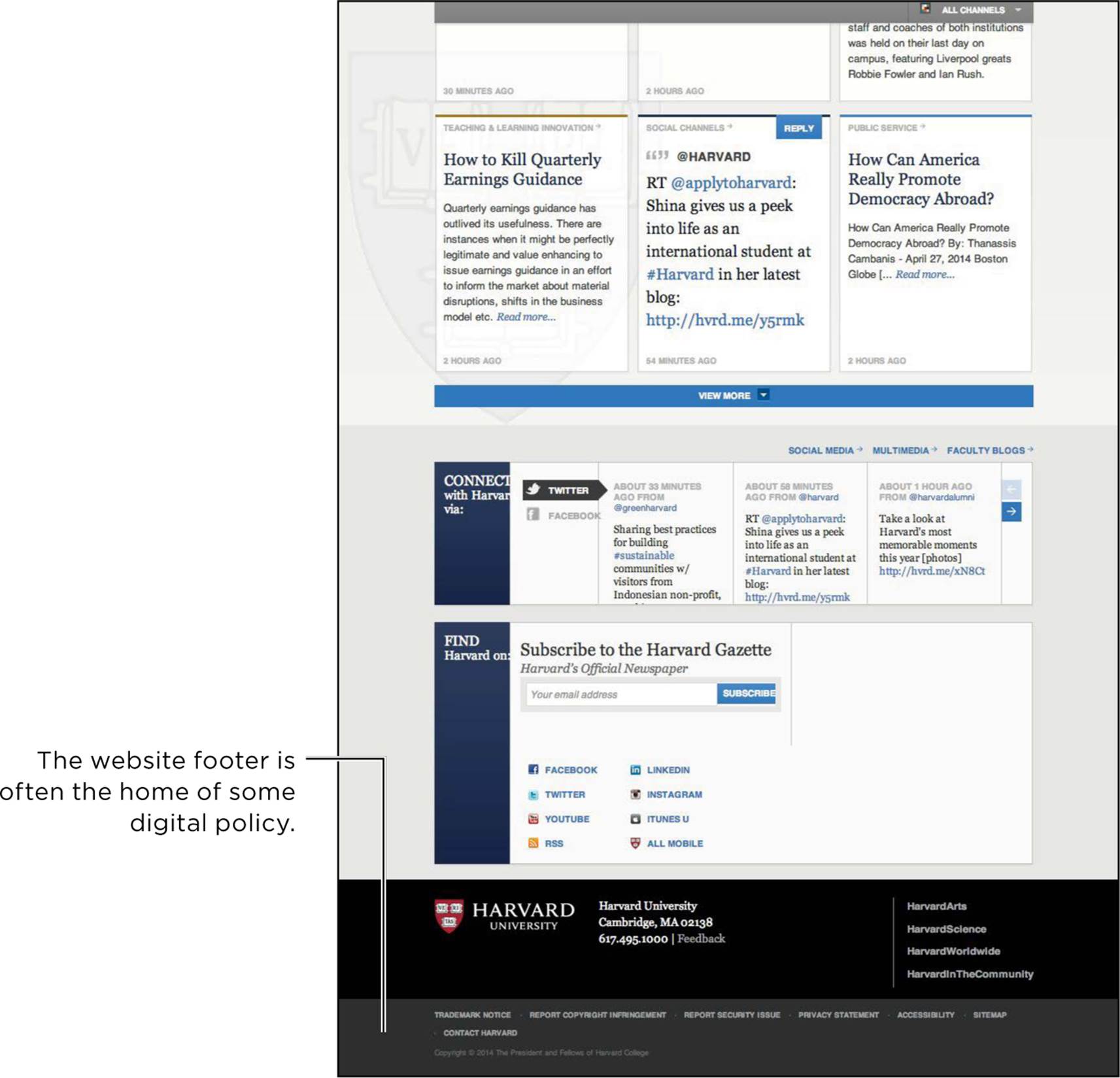

Go to the website of a major organization. Now, scroll to the bottom of the page and look at the footer. Usually, the website footer is the domain of digital policy, as shown in Figure 4.1. That’s because in many organizations, website footers are where you will find a link to the privacy statement and some sort of terms-of-use. There may also be a link to digital security, copyright, and accessibility information. Most often, when reviewed, users will see that these are actually digital policy statements—promises and intentions articulated by the organization regarding their online behavior. Sometimes the statements take the tone and complex language structure of a contract. Sometimes they are written in plain language. And sometimes both are true.

FIGURE 4.1

You can find policy references in the footer of Harvard’s website.

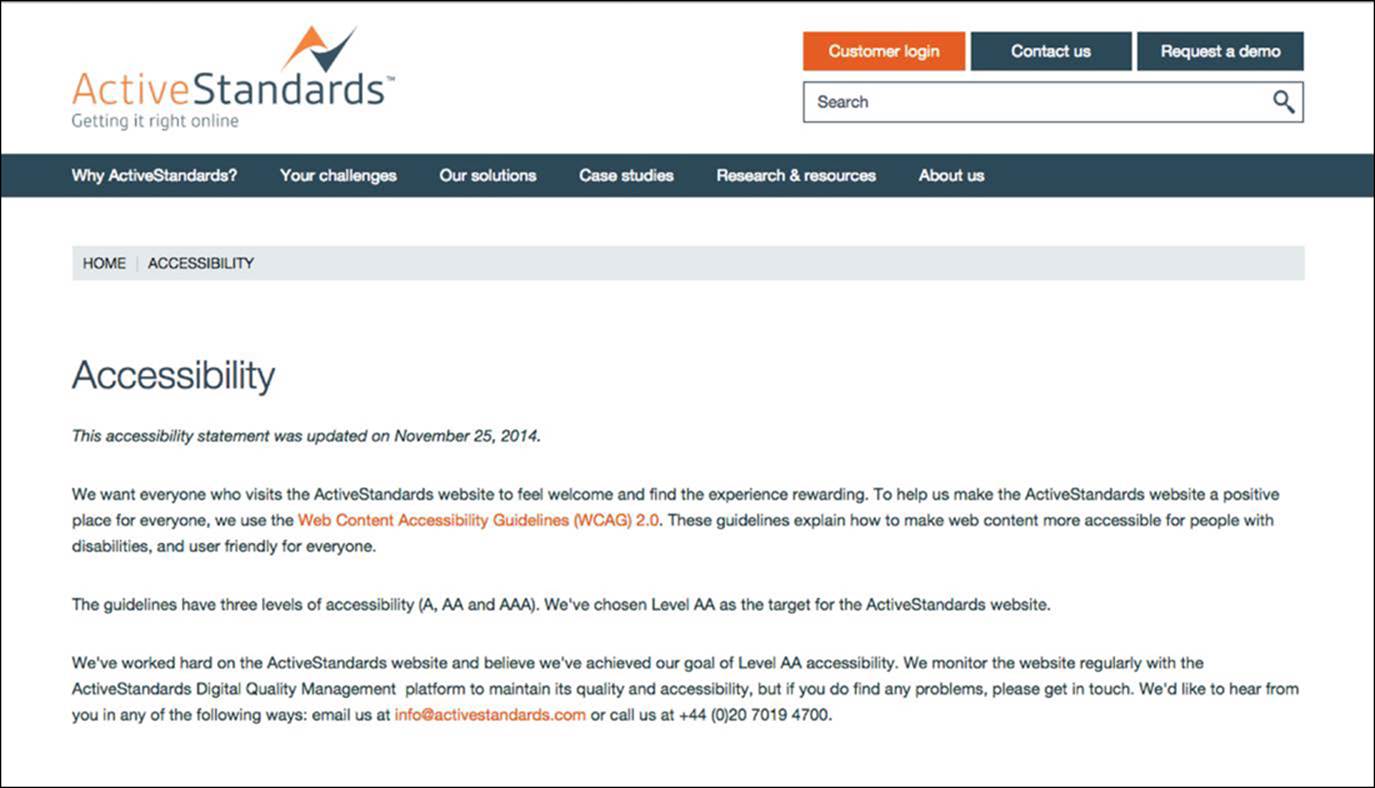

Although privacy, security, accessibility, and copyright are important policy topics, they are really only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to digital policy (see Figure 4.2). But, for many organizations, these few statements resting in perpetuity in the footer reveal the full extent of an organization’s attention to digital policy. That’s unfortunate because the domain of digital policy is much broader than these few statements, and it extends beyond technical and communications concerns to broader corporate policy concerns, such as records management, intellectual property, and branding.

FIGURE 4.2

It’s important to state your website’s accessibility policy somewhere.

Finding Your Digital Policy

There are three main areas of digital policy that an organization needs to examine to ensure that their policy is complete:

• Policies that are new to an organization because of the advent of the commercial Internet and World Wide Web. Examples of these sorts of policies are social media and domain naming policies.

• Policies that existed prior to the advent of the Internet and World Wide Web (WWW), but have been substantially impacted by these platforms. Examples of these types of policies are accessibility and privacy policies.

• Corporate policies that may appear to be unrelated to digital, but may need to be revised due to tacit assumptions. Examples of these might be records retention policies where the legacy policy authors may have assumed that information dissemination would take place via paper or fax. The advent of the WWW has likely introduced new information dissemination practices, and therefore, some policies will need to be revisited and likely revised in order to ensure that they take into consideration any new risks and opportunities due to the use of online channels.

Often, organizations only tackle the first two of these three categories because the policy effort is driven by digital managers or IT resources that have a limited perspective. For instance, marketing and communications resource teams are very tuned into digital policy and standards concerns, but they not as aware of other types of risk associated with operating online, such as the impact that creating new website content might have on a corporate records retention policy that specifies what information needs to be kept for how long (and in what format) within an organization.

At the other end of the spectrum, there is the technical team. Their view of Web and mobile sites is generally hardware and software-focused, and more specifically about the reliability and security of such. So their perspective might cover a policy on the use of “cookies” and tracking devices, security, domain name management, and so on.

Some organizations will need to dive deeper or further categorize policy based on their business needs. For instance, organizations that support a digital presence of interest to children may have a specific children’s online privacy policy, or those businesses in healthcare may need to address patient and medical information privacy concerns directly. Sometimes, multiple policies might have to be drafted to address certain geographic regions.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Remember that digital policy extends beyond the usual copyright, terms of use, and privacy policy that can be found in many website footers.

Policy Is Boring and Standards Aren’t

While many digital workers like to debate and discuss digital standards (see Chapter 5 “Stopping the Infighting About Digital Standards”), particularly those related to graphic design and information architecture, few of them are rushing to debate the nuances of digital policy. There are a couple of reasons why:

• Digital policy can be perceived as boring and off-task. For most staff involved with websites and social channels in an enterprise, discussing digital policy is not as interesting or exciting as discussing digital standards. Take your pick. Do you want to talk about the design for the new website or the Web records retention policy? Or do you want to deploy new social media applications on your intranet or talk about the social media policy for employees? Of course, there are those resources, such as enterprise records managers, human resources, or your in-house legal department, whose job it is to discuss and detail these concerns, but they are usually not front and center in the organization—let alone integrated into digital developments concerns.

• Interest and expertise don’t always intersect. Those people who are most likely to be interested in managing risk for the organization, like a compliance, legal, or auditing department, are not usually the most Web–aware in the organization. Likewise, those people who are in a position to understand the risks inherent in operating online, such as digital managers, user experience architects, and applications developers, are not always organizationally savvy enough to communicate these risks to senior leadership—let alone define policy. So, even when there is significant risk due to a lack of digital policy, identifying that risk and addressing it can often be a task that is left undone.

Because of these two dynamics, many organizations just stick to the bare minimum as it relates to digital policy, where the digital team pushes policy development aside in favor of the “real” or more personally engaging work of defining digital standards. That’s a mistake for two reasons:

• Policies help protect the organization from loss of revenue, relevance, and reputation due to unfavorable or illegal online activity. (Read: If you mess up here, you may not have a job.)

• Policies enable targeted and beneficial digital development by providing fundamental parameters for digital development.

Policy achieves these two goals by specifically including or excluding certain behaviors and developmental activities of the organization. For example, it’s all right to have an organizational Twitter account, but if you are the social media moderator, don’t air your personal political views on that account. These types of constraints might seem obvious or the sorts of things that an organization might be able to take for granted, but in my experience, all sorts of things can and do happen on organizational websites and social channels. While it’s important to allow employees to have a level of autonomy in getting their digital work done, it’s also important to consider and manage the risks that might really impact an organization’s viability. That’s the job of digital policy.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Try to turn a policy into a standard. Policies should not contain design specifications and code snippets. Manage the risk with the policy. Leave protocols to the standards arena.

Policy Attributes

A policy is by nature general, and it identifies the corporate rules. The fact that it consists of brief statements does not mean that it is unenforceable, because a well-written policy will explain why the rules exist, when to apply them, to whom they apply, and what the consequences are if the rules are broken. You should consider the following attributes when creating a sound and strong policy:

• Contextual: The policy should consider the corporation in the context of its regulatory industry and public perception, at the local, regional, national, and global level in which it operates. It should consider the regulatory and legal ramifications of operating digital communications in this outward-facing context.

• Inclusive: The policy should consider the impact of all audiences directly or indirectly impacted by the policy and involve interested parties directly. It also should consider the ability to adopt and comply with the policy. (Note: I often see incremental adoption of a policy and subsequently recommend remediation versus penalty consequences.)

• Realistic: The policy should have a level of realism associated with it. In other words, the policy cannot express such a high standard that it is so unrealistic that it will never be completely achieved by those tasked

• Enforceable: The policy should be written so that those responsible for policy compliance can actually measure its compliance. Codifying policy in such a way that an organization has no way of determining whether or not it is being adhered to by stakeholders only weakens the policy domain.

• Rooted in Evidence: A policy should be rooted in expert opinion and industry practices. Rooting policy in applicable legal findings and rulings further ensures that the organization is well protected.

• Comprehensive: The policy must be holistic and look beyond the digital boundaries to the organization’s strategic objectives (and, at times, those of the parent company) to establish the legal, moral, and ethical foundation for the policy. Cross-organizational objectives may need to be reflected (example: the need for communications to broadcast information and for security to protect sensitive information from being broadcast), and thus collaboration must be established and the joining of interests adopted into the policy.

While all of these attributes will not be written into the policy, the policy embodies all of these attributes.

Identifying a Policy Steward

When establishing your digital governance framework, it’s essential that a policy steward be assigned. The digital policy steward must be able to strike a balance between the benefits of mitigating organizational risk associated with digital activities and the benefits associated with capitalizing upon and exploiting digital channels for fiscal and mission-related gain. That means that policy stewards need to be able to take an objective and dispassionate view of digital. For this reason, corporate legal is often a natural home for digital policy stewardship, but certainly not the only one. There are other compliance-focused or risk-management focused areas of organizations that are equally well positioned to serve the role of policy steward.

Usually, hands-on digital workers aren’t my first pick as policy stewards. Often, they are too apt to minimize the risks associated with online development and, more importantly, can be ignorant of legislation that may impact policy choices. That doesn’t mean that digital workers should be excluded from policy. As you’ll see later, they are integral to the policy authoring process.

NOTE RESPONSIBILITIES OF A POLICY STEWARD

The policy steward often has the following responsibilities:

• Ensures that the organization establishes and maintains a full set of relevant policy.

• Effectively disseminates policy to the appropriate stakeholders.

• Rationalizes corporate policy and digital policy.

• Monitors shifts in the external Internet, World Wide Web, and other vertically specific policy and compliance concerns.

NOTE CHARACTERISTICS OF A POLICY STEWARD

Most policy stewards exhibit the following characteristics:

• Understands and applies laws and regulations related to the Internet and WWW to the organization.

• Understands and interprets laws and regulation for the organization’s market segment.

• Understands high-level organizational objectives.

• Acts as a mediator between various organizational interests with an objective viewpoint.

Despite the reality that corporate legal, on the face of it, appears to be a natural home for digital policy stewardship, in practice, legal departments and other aspects of “corporate” can be functionally detached from the digital policy stewardship process. Usually, this isn’t a rejection of the role, but rather a maturity concern. Typically, a legal department is accustomed to weighing in on the footer polices mentioned earlier because they have an established relationship with the IT department that is focused on aspects of security and privacy, as well as a relationship with marketing and public affairs, which often oversee the substance of copyright and branding policy. But digital is still new enough that many of the more subtle implications of its impact on policy are in the legal department’s blind spot.

So legal resources that typically would ensure proper risk management in other areas of the company don’t necessarily know or understand the risks associated with digital. For instance, a legal department may not consider that the lack of a domain naming policy might mean that there are no standards in the organization regarding who is allowed to buy domain names (and subsequently put up Web and mobile sites in the company’s name).

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Assume that your legal department will know when to step forward to address digital policy considerations. Often, the legal team lacks the digital expertise to identify when and where online risk exists.

In practice, I have worked with large, global companies that have no idea how many websites they have online or who is making content for them. That sort of behavior represents unmanaged risk. It’s the role of the policy steward to ensure that digital risk is effectively evaluated and the range of policies defined in an organization is appropriate for managing that risk.

Assigning Policy Authorship Responsibilities

Policy authors must consider the variables that inform a policy (risk, law, regulation, and an organization’s digital strategy) before they create an informed policy statement. At times, a single policy might require contributions from multiple authors. But, from a process perspective, it’s important that there be an author “owner” who is committed to having the appropriate discussions with stakeholders and making the first attempt at drafting the policy.

NOTE RESPONSIBILITIES OF A POLICY AUTHOR

The responsibilities of a policy author encompass the following tasks:

• Speculates and interprets the impact of digital activities on the organization.

• Defines an organizational position on a particular policy topic.

• Drafts and maintains digital policy.

NOTE CHARACTERISTICS OF A POLICY AUTHOR

The characteristics of a policy author are the following:

• Liaises with organizational and digital subject matter experts to envision and articulate the tactical and organizational implications inherent in implementing certain functionality.

• Speaks of digital in “plain language.”

• Understands the high-level implications of certain tactical digital development choices.

Because of the subject matter diversity of policy, authorship is usually distributed across the enterprise. If policy is being authored in a centralized manner from one vantage point of the business, there should be strong concerns that the full policy picture is not being considered. The informed opinions of legal, marketing, communications, technology, and Web experts, as well as business and programmatic resources, are needed to draft effective policies. Exactly where a specific policy is authored in the enterprise is subject to the peculiarities of an organization’s history, structure, management style, and so on. For guidance, consider using the authorship responsibilities in Table 4.1 as a starting point.

Remember, policy might revolve around a particular competency or organizational concern, but it is meant to protect the interests of the entire organization. Policy authors should make sure that they consult with the right resources when necessary. Your legal department ought to be able to offer insight related to external legislation, regulation, or policy that may shape your organization’s online behavior and point out links to and implications for other corporate policies, such as privacy, copyright, and records management. Marketing and communications resources are often the last word on corporate branding, including matters related to visual identity. Finally, technologists understand IT security, and digital experts are a wellspring of expertise when it comes to understanding the practical implications of digital functionality, including information architecture and keyword tagging.

TABLE 4.1 POSSIBLE POLICY AUTHORS

|

Policy Topic |

Candidate(s) for Primary Author |

|

Accessibility |

Accessibility officer |

|

User experience architect |

|

|

Branding |

Marketing |

|

Communications |

|

|

Public affairs |

|

|

Digital Records Management |

Records manager |

|

Senior Web manager |

|

|

Domain Names |

Information technology, marketing, public relations |

|

Senior Web manager |

|

|

Compliance |

|

|

Hyperlinks and Hyperlinking |

Web team |

|

Information technology |

|

|

Communications |

|

|

Intellectual Property Protection |

Legal |

|

Compliance |

|

|

Branding |

|

|

Senior Web manager |

|

|

Language and Localization |

Communications |

|

Public affairs |

|

|

Legal |

|

|

Human resources (for intranets) |

|

|

Privacy |

Legal |

|

Information technology |

|

|

Security |

Information or security officer |

|

Social Media |

Senior Web manger |

|

Human resources |

In my experience, when policy is segregated from the more tactical struggles around standards definition (like the look and feel of a website homepage), debates about the substance of the policy are minimized. That’s because most digital stakeholders aren’t interested in risk; instead, they are interested in what their websites look like and where their content is on the site. However, sometimes there are debates about how much risk an organization should be willing to take when operating online or defining the organization’s online identity. An example might encompass debates about the use of social channels. For example, what are employees allowed to say on behalf of the company and what are the consequences if an employee steps “out of bounds?” Or a policy debate could be about the interpretation of the law, because often national and local laws have not caught up with the realities of digital. Or the debates could be about the culture and values of an organization versus profitability (user privacy vs. using “big data” to your advantage). So, you’ll often find ambiguity and real options that must be discussed before forming a policy statement.

Because of the impact of policy decisions, when there is a lack of consensus about the substance of the policy, those concerns are best escalated to the appropriate management level. Policy positions can and do impact the core of an organization’s viability and culture. If there are debates in this area, they are best addressed by the people who hold accountability.

Writing Digital Policy

I’ve worked on projects where the corporate process for codifying policy was so troublesome that many of the people on the digital team just didn’t do it. That’s the wrong choice. I understand that impulse, but policy is too important—if only to inform the more resonant set of protocols: digital standards—and, as you’ll see, everyone cares about digital standards.

Many organizations have an existing process and template for drafting, codifying, and disseminating corporate policy. If digital policy is to be taken seriously by everyone in the organization, then the policy steward should ensure that this standard process and template are utilized—even if they are arcane. This might be repugnant to those who work in the user experience arena or to writers or Web managers who are used to just getting things done. But, if there is an opportunity to improve the process and template or to impact the quality and clarity of the policy communication, then go right ahead. Just don’t stall the process of establishing digital policy in order to do so.

Whether your organization already has a framework for establishing policy or not, there are some good practices related to structure and content to consider.

1. Use a standard format: Policy by its nature is not necessarily an interesting read for most. So try to use a standardized document format for all digital policy so that your community knows where to look for information that is relevant to them. Components to consider are:

a. Policy title: What is the policy about?

b. Policy summary: What is the gist of the policy in plain language?

c. Related polices and standards: What references to other policies and standards could be impacted?

d. Policy revision date: When was this policy last updated?

e. Policy scope: To what digital artifacts and products does this policy apply?

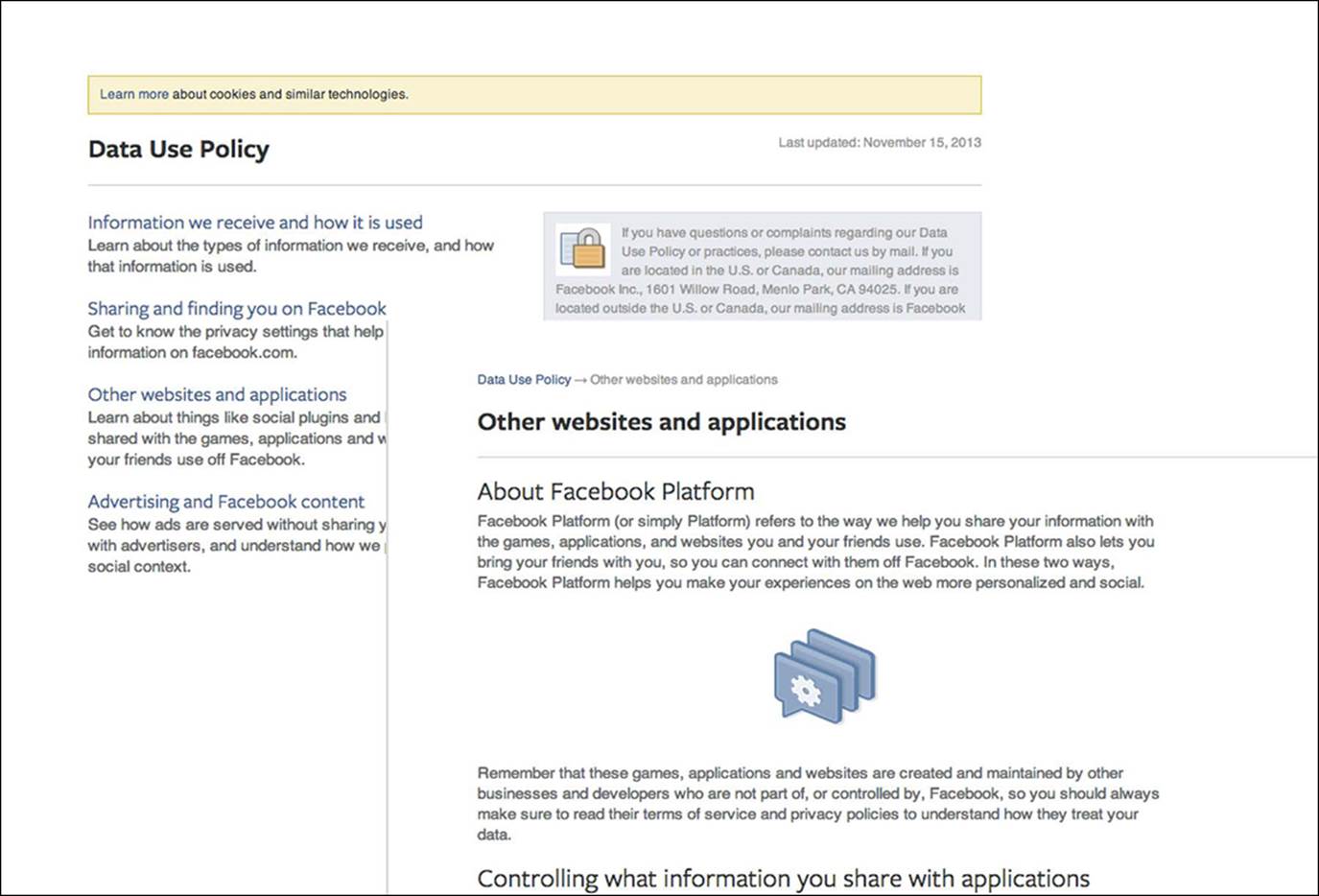

2. Use language that people understand (not jargon): Sometimes, after all the legal and regulatory concerns have been addressed with precision, corporate policy can be dense and difficult to comprehend for the average employee or customer. You’ve all read incomprehensible privacy statements on websites. The policy author should ensure that policy statements are summarized and communicated in a language that everyone understands (see Figure 4.3). In my experience, sometimes those who are most impacted by policy—the people who write the code and manage the corporate website—are the ones who are least informed about digital policy. Often, this situation occurs because the policy language is arcane and the applicability of the policy to everyday digital work is not clear.

FIGURE 4.3

Facebook uses ordinary language to explain policy.

3. Be inclusive: Remember, policy is meant to protect the organization, so the entire organization should be considered for input. The policy perspective of an aspect of a business that operates in Canada might be very different than the perspective of those working in Spain. Your legal department ought to be able to offer insight related to external legislation, regulation, or policy that may shape your organization’s online behavior and point out links to and implications for other corporate policies, such as privacy and copyright and records management. And your digital team can illuminate exactly what is happening with information that is collected on sites and via various applications and processes. Lines of business, product lines, or other organizational divisions also have a relevant viewpoint. They know what they are trying to achieve from a fiscal and mission perspective—whether that’s ramping up sales in a particular product line or recruiting more students to a particular area of study for a university, or something else. It takes a village to draft a digital policy. So err on the side of inclusion instead of exclusion.

4. Vet with the experts: No matter who is consulted during the drafting, two areas should review any digital policy that is written: the core digital team and the legal department. The digital team should determine if the policy is realistic, given the reality of online tactics. After the policy has passed the digital team practicality test, its next stop should be legal—which often has the final set of recommendations for revision. Usually, there is a back and forth between the legal team and the digital team as they find the right set of constraints that will enable the enterprise to do business effectively online and protect the organization from litigation or other negative factors. Revision and negotiation are usually required at this point. Sometimes, when there are tough choices to be made, senior management or executives may need to weigh in on the matter to make a judgment about how much risk the organization is willing to take in order to achieve a certain goal.

5. Formalize: If it is to be complied with and otherwise taken seriously during the normal course of business, policy must be codified and disseminated to the organization. Many large organizations have a formal process for accomplishing this. Sometimes it involves assigning a formal policy document number and integrating it into the larger set of corporate policy. Sometimes the document just needs to be posted online on the employee intranet or on the website. In the most formal of situations, an executive signature may be required as well. The policy stewards, if well selected, should be aware of this process and shepherd any new or revised policy through the gauntlet of codification.

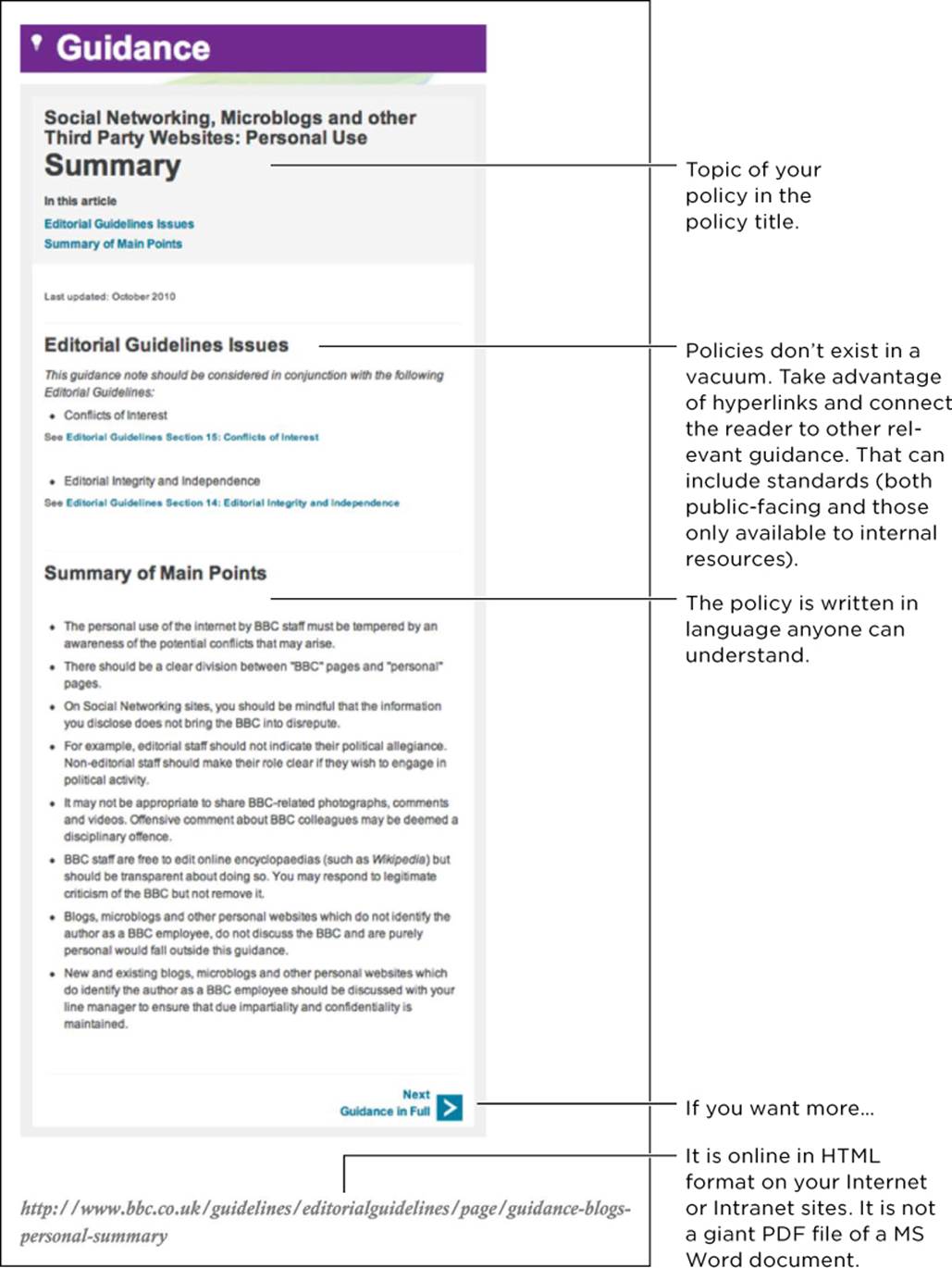

6. Communicate: Whatever your organization’s codification process is, make sure that the policy creation process doesn’t stop there. It’s important that all stakeholders are aware of new and revised policy, especially if those stakeholders are the public (see Figure 4.4). Some areas, such as the website privacy, security, and accessibility policy, are easy to find because they end up in the footer of the website. But it’s important to know where the more obscure policies are housed and make sure that those who are involved in digital development—the full digital team—know where those policies are located. Often, people find that locating existing digital policy is tantamount to conducting an unfruitful archeological dig on the organizational intranet. That’s not a good thing.

FIGURE 4.4

An example of the BBC’s policy with my annotations.

7. Keep it up-to-date: Digital policy (and standards) exist and serve a very specific role in an enterprise digital ecosystem. Sometimes the process for establishing digital policy can be considered a terminal, one-time process. But it’s not. Your policy has to remain accurate over time. If your digital information practices change, your policy should change. For example, your privacy policy might need to change so that you do not use information collected under the earlier policy without getting permission (even if is implied) from those users.

It is important to understand that policy stewards and authors must be vigilant, staying up-to-date with the implications of the latest technology and content trends to ensure that the policy is revised when necessary and continues to protect the interests of the enterprise.

8. Retire at sunset: Digital policy, like other artifacts, can become arcane and irrelevant. It is important to understand when it is no longer needed and retire it in favor of a new policy, or in some instances, no policy at all. Most often, you’ll see the “sunsetting” of policy during mergers and acquisitions or a change in the regulatory operating environment. While infrequent, this stage is part of the policy lifecycle, and rather than simply updating it, you should always review the policy for its relevance and necessity.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Think about policy that might be relevant for your particular marketspace—particularly if you function in a heavily regulated industry like financial services or pharmaceuticals.

Raising Awareness About Digital Policy

Whose job is it to initiate the process of digital policy development in your organization? In the early and immature stages, that answer is simple: If you see something, say something—even if you are the junior-most application developer or a graphic designer. If you see risk to the enterprise, raise your concerns. Websites, mobile sites, and social software interactions are still relatively new entities inside organizations, and you can’t rely on those people who are higher up to be able to recognize and understand risk associated with doing business online.

If you are a junior-ish editorial resource in the public affairs department and you know that there are 17 social media accounts being moderated by people who aren’t fully considering the viral nature of social media channels, and you know your organization doesn’t have a social media policy about this behavior, bring it up. Get the conversation started. You don’t have to be the last word on the matter, but you can be the first. Express your concern to those who have the authority to impact change. Try not to use a lot of technical or marketing jargon. The legal or compliance departments usually care about digital policy concerns, but often no one has taken the time to speak to them about the risks in a language they understand.

If you are a Web manager or digital director and want to help non-Web savvy resources understand the risks associated with certain online practices, use screenshots to show examples of redundant or outdated content on your sites and link that situation to the absence of a Web records management policy (and supporting standards). Or, if you are managing an intranet, consider communicating knowledge management concerns related to, say, the proliferation of largely unmanaged SharePoint instances on the intranet and how they might contain human resource-related information that may or may not be what your organization wants to communicate to its employees.

DIGITAL POLICY CONSULTANT

Kristina Podnar

Policy is intended to create a framework for behavior that is aligned with the governing body of an organization. If you want people to read (and follow!) your policy—whether they be website visitors or employees working on digital content—you should keep it short and written in plain language. You should state the “what” and “why” within several sentences, or a paragraph at most. Your goal is to clearly and quickly explain to the reader the impact on them as a result of using the digital content (for the website visitor) or how they should behave in creating the digital content (for the digital worker). If you find it necessary to document additional details, such as the “how” to execute within the context of a policy, you should develop a companion operating procedure.

Summary

• Policies exist to manage the risks associated with operating online. Your legal department, privacy and security officers, and digital experts will be integral in establishing an appropriate set of policies.

• When considering policy development, it’s important to examine existing corporate policies, as well as IT and marketing-focused policies, that may have been impacted by digital. New polices may need to be written because of the advent of the Internet and the World Wide Web.

• Organizations should appoint a policy steward to ensure that the organization is drafting an appropriate set of policies and that the policy is properly codified in the organization.

• Policy authoring should be an inclusive process that leverages the varied skill sets of organizational stakeholders from IT, marketing, public relations, or divisionally focused entities.

• Make sure that you use a consistently structured format for authoring policy and that you write your statements in plain language and that your policies are properly vetted and codified according to organizational processes.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.