Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART I

Making a Digital Governance Framework

CHAPTER 6

![]()

Five Digital Governance Design Factors

The Five Factors

Factor 1: Corporate Governance Dynamics

Factor 2: External Demands

Factor 3: Internet and World Wide Web Governance

Factor 4: Organizational Culture

Factor 5: The Nature of Your Digital Presence

Don’t Give Up

Summary

Digital governance frameworks would be easy to design if they existed in a vacuum. But they don’t. There are many pre-existing organizational factors in every business that influence which aspects of an organization ought to be accountable and responsible for making decisions about what’s happening online. Sometimes the dynamics of these factors are so hard-wired into an organization’s operational processes that they can be difficult to change. Staff and management feel that these dynamics are somehow ordained and immutable—“We’ve always worked like this.” Or, more strongly, “We must work like this.” But, in reality, almost anything in an organization can and does change, given the right forces, including its core products and services and certainly the way it governs itself.

If you look at the antecedents and history of many long-lived organizations, the strategic goals, products, services, and supporting management structures have likely changed significantly over time. Sometimes an organization’s ability to transform in the face of new technologies or political and social trends is the root of its long-term strength, and in other instances, an organization’s loss of core can be the beginning of its demise. This means that when organizations do change longstanding product lines or business practices, they usually do so only after serious consideration and evaluation of many factors or in reaction to subtle or brazenly disrupting market forces—like the Internet and the World Wide Web.

This tug of war between how organizations have worked and made decisions in the past and how they will need to work and make decisions in the information age will come to the forefront as you design your framework. There will be a dance between the existing dynamics of the organization and what digital demands at every stage of your governance framework design process—even more so once you begin the tactical work of defining strategy, policy, and standards.

Often, when organizations feel this dissonance during their digital governance design efforts, they stop. They feel that the design effort is not worth risking some organizational discomfort. In organizations whose core products and services are being disrupted by digital, failing to push through this dissonance to some conclusion is often a mistake, because they fail to thrive. If an organization is not immediately or fundamentally disrupted, then it may be able to afford to be less decisive about evaluating the impact of digital and formalizing digital governance. However, eventually, all organizations will have to have the tough conversations. Because of this, proactively addressing digital governance is much easier than being forced to do so in a reactionary mode when organizational competitive forces are compromising viability.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Remember that every digital governance framework is unique—impacted by a blend of organizational goals, culture, and the unique history of how digital came to be in the organization.

The Five Factors

There are five factors that regularly influence or are influenced by the digital governance framework design process. Openly considering these factors when designing your framework will help your organization remain vital and relevant, while at the same time absorbing the reality of the changes that the Web and Internet have enabled. The factors are the following:

• Corporate governance dynamics

• External demands

• Internet and World Wide Web governance

• Organizational culture

• The nature of your digital presence

How each of these factors impacts your organization will be unique. But, when undertaking the design effort, the framework design teams in all organizations will have to ask the same question: Do we change the dynamics of this design factor to suit the needs of digital, or is the substance of this dynamic so integral to the business that digital must follow its lead?

Factor 1: Corporate Governance Dynamics

Digital governance is a subset of corporate governance. So, naturally, an organization’s digital governance framework will be heavily influenced by how that organization governs overall (see Table 6.1). At the most basic level, if an organization does not govern well on the whole, it’s also likely that this same organization will find designing and implementing a digital governance framework difficult.

For many organizations, the digital governance framework design effort is the “tail wagging the dog” in the corporate governance arena. For instance, the framework design team may find itself challenged to determine who has decision-making authority around graphical user interface design standards in an organization that has difficulty establishing authority for corporate visual identity and brand standards. Or the team may find it impossible to establish a policy for Web records retention when their organization has no formal records management policy.

TABLE 6.1 HOW CORPORATE GOVERNANCE INFLUENCES DIGITAL GOVERNANCE

|

Corporate Governance |

Digital Governance |

|

|

The logical, legal, and fiscal structure of the organization |

influences |

the digital team structure and budget. |

|

How and where organizational goals and success metrics are defined |

influences |

who defines digital strategy. |

|

Which organizational entities oversee and author corporate policy |

influence |

digital policy stewardship and authoring. |

|

How the organization makes decisions about shared initiatives and shared infrastructure platforms |

influences |

patterns for digital standards, authoring, and stewardship. |

Alternately, if an organization governs well, introducing the idea of digital governance may not be as challenging. However, even when organizations have developed some governance maturity like those that function in more heavily regulated sectors such as pharmaceutical, finance, or healthcare, they may only govern certain aspects of their business well.

Within a single organization, there can be multiple governing styles of governing. And, that’s okay. Businesses are systems with nodes of specialization that don’t all need to be governed or managed in the same manner. Your objective is not necessarily to mimic existing organizational governing dynamics, but rather to ensure that the digital governance framework integrates well with existing governing dynamics and supports your organization’s ability to do its job well—whatever that might be.

In any organization, multiyear plans, strategies, and performance measurement paradigms often align with the grid of fiscal management. For example, managers typically measure their corporate authority by the size of their budget and the number of headcount over which they have authority.

But, sometimes, digital efforts and effective governing practices cut across or run against these existing realities. For instance, the biggest (from a headcount perspective) and most profitable product line in an organization might be accustomed to basically doing whatever it likes in an organization. However, a specific dynamic, such as growing ecommerce channels, might serve to reduce that traditional authority and profitability. That can make for a tough transition for the people.

If there are aspects of your digital governance framework that require you to change the way you fund digital or don’t align with the existing power hierarchy, then you should expect significant pushback. That’s why, as you’ll see in Chapter 7, “Getting It Done,” all digital governance framework design efforts require senior leadership advocacy and sponsorship.

Factor 2: External Demands

Organizational digital systems exist in a broader ecosystem—one that extends beyond the boundaries of the organization. And that larger system often imposes requirements on an organization. Those requirements might influence who within your organization is allowed to make decisions about certain aspects of your business, including policy and standards. For digital, those demands usually fall into two categories: demands driven by the marketspace in which an organization does business and demands driven by the geographical location of where a business operates.

Market-Specific Demands

Sometimes the marketspace in which an organization does its business impacts the designation of strategy, policy, and standards decision-makers. For instance, businesses operating in the financial sector may have a legal requirement to establish a separation between certain business entities. That separation can extend to the people who are allowed access to certain information and the people who have fiduciary responsibility for various organizational subdivisions.

Superficially, this may not appear to be of concern to digital workers, but these divisions can and do impact how financial organizations cross-sell their products and services in the real world and online. Most people have experienced calling their banks to discuss their checking and credit card accounts and being transferred from division to division. While some of this behavior represents bad customer service, some of it is legally required. These same sorts of divisions can and do surface online and will impact the design of your framework, as well as your websites and supporting back-end systems.

It’s important for organizations to understand, in detail, these sorts of compulsory separations. Frequently, digital workers get so focused on possibilities related to cross-channel selling that they don’t stop to reflect on these deeper concerns. And, if an organization’s legal department’s awareness of digital is low, an organizational Web presence can unwittingly find itself out of compliance with industry-specific regulations. If these types of separations are considered and discussed in full when designing your digital governance framework, there is less chance that certain regulatory lines will be crossed in the enthusiasm of implementing new online functionality.

Geography-Related Demands

Depending on where your organization operates, regulations around the use of and access to the Internet and World Wide Web will differ. In recent years, businesses in the EU have dealt with shifting information, as it relates to the use of “cookies” and other Web browser-based tracking devices. In addition, many governmental entities have established rules about what can be viewed and sold online. For instance, in the United States, certain states prohibit the shipment of alcohol, which means that customers in those states can’t buy a bottle of wine and have it shipped to their home. When considering the strategic aspects of social media organizations, your company might need to know that Facebook is blocked in China, or that LinkedIn is not an effective vehicle for employee recruitment.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Remember that organizations that function globally may have more complexity in their framework—particularly when it comes to stewardship of digital policy.

Because of these dynamics and the ability to operate in many regions and nations, global businesses have to take special care in considering how policy and standards will be crafted and by whom. Their policy must be aware of and reflect national regulatory concerns, as well as regional and cultural norms. For instance, if an organization’s website homepage features prominent imagery, that imagery must be appropriate for every country, and if not, the organization might need to localize that imagery (see Figure 6.1). This restriction can impact who should be designated to make certain decisions about design and editorial standards in the organization and what work gets done in the core and distributed digital team—thus, it impacts the digital governance framework.

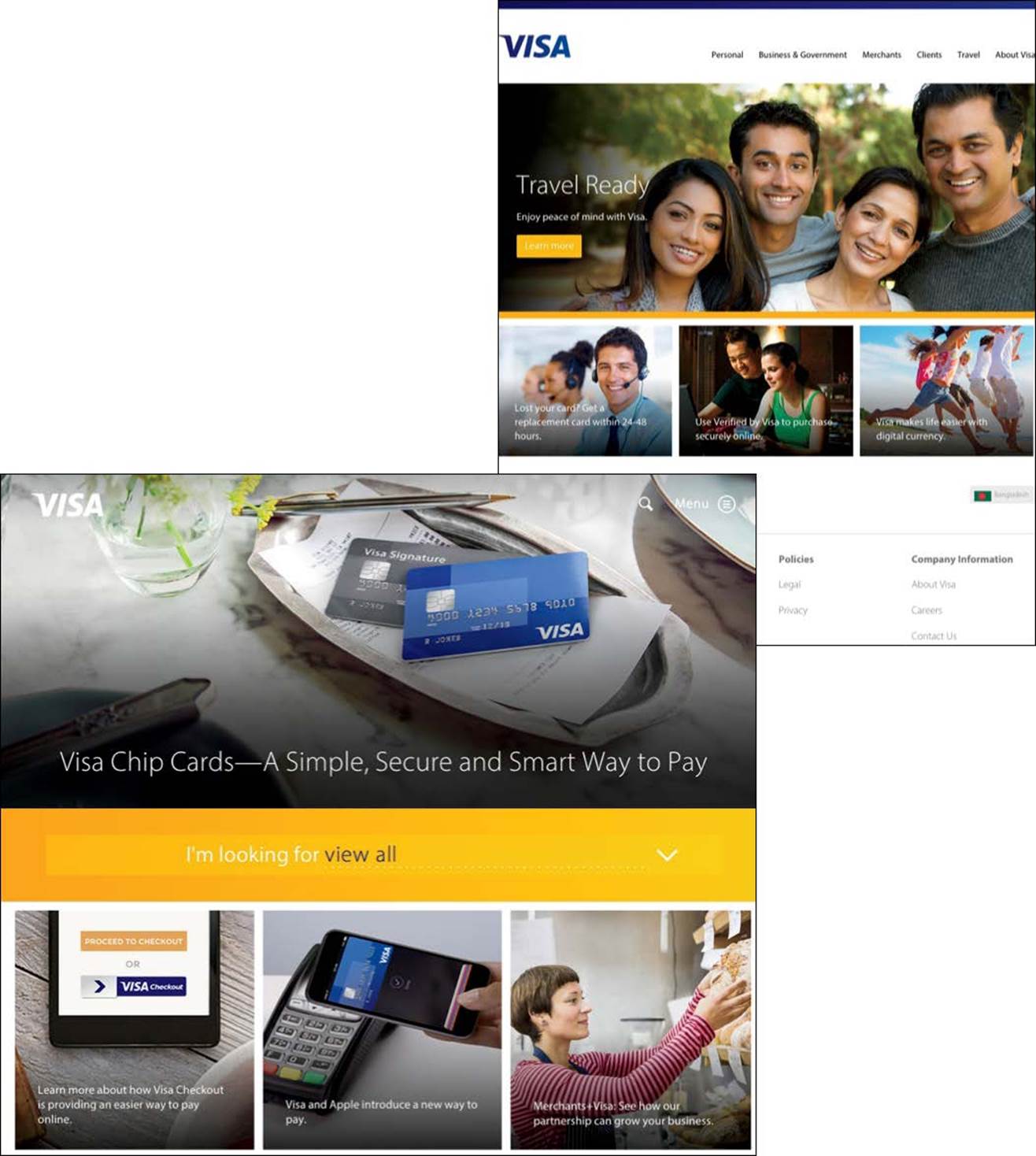

FIGURE 6.1

The homepage for Visa in the United States and Bangladesh.

On the whole, it’s important to remember that even after 20 years, digital is not a mature business space in the commercial Web. Organizations are still figuring out how to utilize digital channels effectively to their business advantage. Outside of commercial business, there is still debate and a lack of certainty regarding how existing local, national, and international laws apply to the Internet and Web, particularly as to how those laws relate to data privacy, tracking, and how much constraint an employer can put on an employee regarding the use of social media, to name a few scenarios. For this reason it’s important to be strategic about the selection of your policy steward in particular because it is that person’s job to keep a finger on the pulse of external regulatory concerns that may impact how your business operates online.

Factor 3: Internet and World Wide Web Governance

For digital professionals, particularly for those people who have spent their entire career in a Web-enabled business environment, it is often easy to forget that the Internet and World Wide Web are relatively new systems for business. More importantly, the actual impact of these systems is ongoing. Web and Internet policy issues are broad and deep and should be on the radar screen of your governance framework design team. It is vital to understand your organization’s place and function within the evolving Internet ecosystem and be aware of significant shifts that might impact business operations and corporate and digital governance frameworks.

Digital governance is at the receiving end of a system of Internet and World Wide Web governance (see Table 6.2), so, it’s important to understand which policy and standards shifts in these arenas might impact how your organization governs its digital presence.

A lot of organizations are largely disconnected from trends in Internet and World Wide Web governance, mostly because the issues being discussed, such as the debate between IPv4 and IPv6 in Internet Governance or the discussion about Open Standards and WWW governance, might not seem to be germane to everyday digital concerns of the business. That might be true for many digital practitioners, but these concerns should be on the radar of policy and standards stewards. Knowledge of these sorts of debates and their relevance to the business should be taken into consideration when designating these roles in your framework. Some other concerns worth noting are the following:

• Ecommerce taxation

• The nature and agenda of the Internet multi-stakeholder governance model

• Network neutrality

• Internet infrastructure development (physical)

• Domain name administration and management

• Personal privacy

TABLE 6.2 THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN INTERNET, WEB, AND DIGITAL GOVERNANCE

|

Scope and Issues |

Interested Stakeholders |

|

|

Internet Governance |

The global Internet Control and management of the physical Internet infrastructure Control and management of domain names and numbers Global access |

The Internet Society (ISOC) Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers ICANN) Internet Governance Forum (IGF) Number Resource Organization (NRO) The United Nations (UN) National Governments |

|

Web Governance |

World Wide Web |

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) United Nations National Governance |

|

Digital Governance |

Organization or enterprise Websites Mobile sites Web-enabled sensors and micro-devices embedded in devices and humans |

IT Marketing/Communications Legal Human Resources Compliance |

What you need to do when designing your framework:

• Designate a policy steward who has the ability to stay abreast of emerging Internet and World Wide Web policy and standards concerns.

• Ensure that both policy and standards stewards can analyze how various Internet and WWW policy and standards decisions may impact the strategic aims of the organization.

• Make sure that your organization is strategically positioned to participate in Internet and WWW-related policy debates when policy outcomes impact the vitality of your organization.

NOTE FURTHER READING

The Next Wave: Using Digital Technology to Further Social and Political Innovation (Brookings FOCUS Book), Darrell M. West

Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance (Information Revolution and Global Politics), Milton L. Mueller

The Global War for Internet Governance, Laura DeNardis, Yale University Press

Factor 4: Organizational Culture

Whether your organization operates in the spirit of open collaboration, highly politicized debate, top-down command and control, or a combination of these and other management styles, your organization’s culture will influence your digital governance framework design efforts. That influence usually manifests itself in three significant ways:

• It may impact the process that is used to create the framework itself.

• It can influence the substance of the framework.

• It could affect how the framework is implemented.

As you’ll see in Chapter 7, “Getting It Done,” it’s important to create an appropriate environment in which to have the tough conversations that will surely arise when you design your framework. Organizations that support a culture of collaboration might want to use a more inclusive and transparent process from start to finish when designing their digital governance framework. Alternately, organizations that have a more hierarchical, top-down decision-making culture may be able to take a more narrowly inclusive approach to framework design. Creating the framework is the first task in the digital governance implementation process. So it’s important to conduct that process in a way that sets the desired tenor and tone.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Be fooled. Just because an organization has a casual business culture, it doesn’t mean that digital governance mechanisms must or need to be equally casual.

Organizational culture can also impact what is possible in an organization as it relates to digital governance. A highly focused, standards definition, decision-making function with minimal stakeholder input might be the most efficient model in some situations and may even support an organization’s digital strategy most effectively, but it may not marry well with an organization where the culture honors inclusive collaboration. In situations like these, the optimal framework might need to bend to suit the culture of the business, or the culture might have to change to support the new demands of digital.

In a for-profit environment, the decisive driver is often a clear one—things like fiscal viability and market-share retention. It makes little sense to maintain what has been a traditional cultural trend while at the same time leading the business’s bottom line down a path to fiscal ruin (although I’ve watched some businesses do so). Reacting to the impact of digital, like all business disruptions, is challenging from a change management perspective. In some organizations, executives might not be equipped for the challenge. A mature business that works in a sector that is largely commoditized simply may not have the type of management and staff in place that are functionally capable of adapting to a deep disruption brought on by digital.

Even if the evolution is implemented, serious shifts in business culture due to the impact of digital may render the business unrecognizable to long-term employees. Managers will have to balance out the importance of employee retention against future business viability. Some organizations don’t have the stomach for that sort of deep transformation. In already heavily impacted market segments, such as publishing, these challenges have necessarily been faced head-on with some organizations going out of business and others transforming almost beyond recognition as digital publishing pushes print publication methods and processes out of dominance (see Figure 6.2).

FIGURE 6.2

Newsweek goes out and then back into print, and The New Yorker puts its archive online.

Culture will also influence how your digital governance framework is implemented. Outside of an online business emergency (such as legislative activity due to questionable or illegal activity online), many organizations will implement their framework over time more quickly or more slowly, depending how the organization manages changes. But some may be able to support a more abrupt shift in governance if the organization has a history of utilizing a more rapid approach to change management.

When defining your framework, it’s important to understand these cultural aspects and push to “do the right thing.” That will require a degree of managerial courage, but if the disruption of digital is real, your organization’s long-term health may rely on the strength of those defining your framework.

Factor 5: The Nature of Your Digital Presence

Of course, the size and range of your organization’s digital presence will impact the design of your framework. In fact, in many ways, those online products and services will have a direct correlation to your digital team structure and decision-making patterns. It seems self-evident, but be sure you understand the full inventory of applications, websites, and social channels being utilized by your organization before you start your design effort. Sometimes, core digital teams try to exert control over their digital presence without really understanding the big picture of what is happening throughout the entire organization. At other times, digital team members can be so hyper-focused on the quality of one digital artifact—such as the main organizational website—that they miss other potentially high-risk digital sites and social channels that require the support of a proper digital governance framework.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Forget that the organization’s online presence is already governed by the Internet and WWW policy and standards. Stay abreast of trends in these two parent-governing systems and influence them when necessary.

A large global multinational B-to-B digital presence will necessarily have a different sort of supporting governing framework than that of a large B-to-B organization that operates in a single country or a large B-to-C company that operates its digital presence in multiple countries. Organizations with websites that carry a heavy transactional volume, like ecommerce sites, will have a different sort of governance framework than a site whose focus is largely information dissemination. And organizations that utilize social channels heavily will govern differently as well.Chapter 7 will detail how you can ensure that you understand the landscape of digital at your organization.

What Does Effective Governance Look Like?

I’ve found that, overall, clear organizational governance is the exception and not the rule. Even when governing practices are clear, the dynamics and culture of an organization can mask what is going as it relates to governance. For instance, most people would think that military environments have command-and-control, top-down governance models and governing norms, but what’s less intuitive is that when it comes to product design, so does Apple, Inc. In fact, in some ways, Apple delegates less accountability and decision-making authority than military organizations.

In the military, command and control is the norm except in certain specific times (like on the battle field) when soldiers are empowered to make decisions without going through the normal command and control hierarchy. So the military wears its governance framework on its sleeve, but Apple (and a lot of other organizations) wraps their governance practices up in a different cultural veneer (see Figure 6.4). If you were to examine Apple’s real approach to governance overall, it might really look like a benevolent dictatorship and, in certain situations, have tighter controls than those in the military.

FIGURE 6.3

Apple iPhones—a product of a “benevolent dictatorship.”

Every organizational digital presence has its own DNA, but there are some common themes that organizations can consider when trying to evaluate how the nature of their digital presence might impact their framework (see Table 6.3).

TABLE 6.3 THE NATURE OF YOUR DIGITAL PRESENCE—DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS

|

Theme |

Questions to Ask |

|

Level of integration |

What is the level of integration with non-digital channel strategies and processes? (If it’s deep, you might want to push for the integration of digital governance with overall organizational governance now.) |

|

Scope of your digital presence |

How many websites, social channels, and mobile apps does your organization support and what is their purpose? Do they all need to be governed the same way? |

|

Localization |

Is your digital presence localized, or is everything served up in a single “international” format? Do you translate all of your content or just some of your content? Who in your organization does the translation? Who does the review? |

|

Rate of change |

Do you update content every minute, hour, daily, or only once a month? How often do you deploy new applications and content? |

|

Content and systems architecture |

How many content publishing systems exist in your digital environment? Who pays for them? How do they intersect with other systems and content on your servers? How is your core digital hardware and software infrastructure architected and administered? |

|

Mission criticality |

Is your digital presence mission-critical to the business? |

Don’t Give Up

The consideration of all of these factors (and others unique to your organization) creates a complex design challenge, which is why a lot of organizations put off designing and implementing a governance framework until the situation absolutely demands it—such as when a website needs a new information architecture or technical platform and the core digital team realizes that they don’t have the authority to effect that change, or when the risk of continuing to operate in an ungoverned manner becomes too great. In those situations, though, it’s unlikely that organizations can take the time to make the right choices. So it’s important to be proactive about designing your framework in advance. Doing it at a time when the organization can take the time to do the job well is important. The next chapter explains how to get this framework accomplished and in place.

Summary

• The nature of your digital governance framework will be impacted by five key design factors.

• Corporate governance dynamics will impact your digital governance framework because digital governance is a subset of corporate governance and will therefore inherit dynamics from its parent.

• Market-specific and geography-specific regulatory musts and constraints will impact your framework design, as will social norms in regions, nations, and locales.

• Internet and World Wide Web governance are the cornerstones of digital governance, and trends in both of these domains will impact, sometimes substantively, how organizations must govern digital.

• An organization’s culture will influence how an organization designs its digital governance framework, what the substance of the framework is, and how it is implemented.

• The nature of your digital presence will drive the design of your digital governance framework, especially the structure, roles, and responsibilities of your digital team.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.