Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART I

Making a Digital Governance Framework

CHAPTER 8

The Decision To Govern Well

Reason One: The Transformation Is Too Hard

Reason Two: We’re Too Important to Fail

Reason Three: We’re Too Profitable to Fail

Reason Four: Difficult People

Moving Forward in Less Than Ideal Circumstances

Internal Alignment

Quantify the Risk

Emphasize the Business Opportunity

Summary

Clearly defined or not, there will always be governing dynamics when a group of people come together to achieve a common goal. However, whether or not an organization governs well is a matter of choice. For organizations that do choose to govern their digital presence well, the rewards can be great, not only for the organization but also for its students, members, customers, or citizens—whoever is interacting with them online. But all too often, organizations of all types choose to ignore the call for sound governance, even when the state of their digital presence or the organizational risk created by a suboptimal digital presence all but demands that governance concerns be addressed. There are a variety of reasons why this laissez-faire attitude exists.

Some of the most frequently heard reasons for not establishing an effective digital governance might sound familiar:

• The diversity of product offerings of a global multinational organization. (“We’re soooo decentralized” or “Every business unit is very, very different. We can’t work the same way.”)

• The intellectual autonomy and stubbornness of a highly educated staff at a university or researched-focused organization. (“Those PhD professors just won’t listen!”)

• The consensus decision-making style of a large non-profit or governmental organization. (“We don’t govern anything” or “We’re not for profit. That changes everything.”)

None of the above dynamics are unique. On the whole, all three of these dynamics exist in every organization I’ve ever worked with—at varying levels; however, none of them are reasons to choose not to govern well. Instead, they are reasons to choose to govern better.

Governing takes work and effort and compromise. Even in organizations where one would think governance would be a no-brainer, like the military, people still have trouble governing their digital presence. That’s because very seldom are those previously stated concerns the real reasons why digital governance has not taken hold. They are just the easy-to-speak-of ones. The real reasons are often much simpler.

Reason One: The Transformation Is Too Hard

Most people will try just about anything to get around a problem before they change the way they work from day to day. I’ve seen business processes that simply made no sense at all, but were in place simply to help preserve legacy work practices. A classic is the marketing team that still produces a print-focused brochure that is never printed and physically distributed, but rendered as a PDF and put online for customers and prospects to read. Why? Because their employees’ jobs are defined and shaped around that process. Or, put more simply, because the organization has always done it that way.

For organizations whose business model was established prior to the advent of the World Wide Web, deciding to change tried-and-true organizational decision-making and accountability norms can be highly political or destabilizing to human resources. As mentioned earlier, certain processes or standards for working may appear to be immutable when, in reality, there are other ways to work. Also, understandably, a lot of people derive a sense of personal power from their position in a management structure, the amount of budget they control, or the degree of authority and negotiating power they have with their peers. All of these things can lead to a gridlock when it comes time to implement a new framework.

Defining a digital governance framework is relatively simple compared to implementing it. Some digital teams see that dilemma coming before they even get started, so they just don’t get started in the first place. That’s unfortunate because, likely, these teams could benefit most from a formalized and well-implemented digital governance process.

For the lucky few, a newly defined governing framework will simply solidify the good digital governing and development practices of an already well-formed digital team. But for most, the framework will represent a (sometimes radical) shift from business as usual. If your framework falls in the radical shift digital disruption camp, then your digital governance efforts might stall after your definition phase. In these situations, sometimes the core team would rather struggle through the pain they know (not enough budget, no executive sponsorship, and an inability to negotiate standards with their digital stakeholders) than venture out into the unknown terrain of digital governance.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Remember that taking back authority from digital stakeholders is tough. If your digital presence and team are already in chaos, don’t expect those dynamics to change overnight.

Reason Two: We’re Too Important to Fail

Sometimes organizations choose not to improve digital governance because they feel too important to fail. In these situations, there is often organizational hubris where organizational leadership feels that their legacy market position or some other level of clout leaves them impervious to the impact of digital—even in the face of real indicators that the organization might be at real risk. Let’s call this the “Blockbuster Syndrome” (see sidebar). But this isn’t just a for-profit stance. I’ve seen this attitude in higher education in instances where elite universities didn’t feel there was a need to improve online student services or consider embracing new trends in online education. This “we can’t fail” attitude can also exist in governmental organizations or non-governmental organizations where adequate funding is almost guaranteed year after year.

In the non-profit sector, there is a combination of these dynamics. Some non-profits or not-for-profit entities have a powerful brand that is distinct from their mission. That identity, coupled with a large endowment and donor pool, can leave these organizations feeling very comfortable, and their leadership feeling as if they can operate by a different set of rules when it comes to digital.

The risk of this sleepy posture is that a complete disregard for governance concerns means that the organization will not be aware when the ground shifts underneath it. In particular, if organizations wholly disregard the digital strategy aspect of governance and fail to make a real connection between digital performance and the overall organizational goals (even when those connections are obvious), they can find themselves ill-prepared to make the maneuvers required to stay relevant or profitable when, seemingly, all of a sudden, the digital disruptions hit their marketspace.

The Blockbuster Syndrome

Sometimes organizations miss the target when it some to digital. I’m not talking about the type or targeting that leads to low user experience or a bad website design. I’m talking about missing the target to the extent that your company goes out of business. While a lot of businesses have been impacted by digital and struggle to come up with an appropriate market response, some seem overly reticent to what many perceive to be an obvious market disruption.

An example of this was Blockbuster’s response (or lack of response) to shifts in the distribution model for at-home entertainment. It took the better part of a decade for Redbox and Netflix to gain market share over Blockbuster. How do companies that “own” a market sector fail so grandly? Factors that come into play in the Blockbuster Syndrome are the following:

A digitally conservative leadership. This might include the executive level and, in some cases, a board of directors that is completely tone-deaf to the market disruption.

A healthy cash reserve. Businesses that are rich in cash often have a lot of room for error—too much room sometimes. That cash comfort affords an organization the luxury of watching a market trend for a while (too long) before reacting.

Underestimating the transformation. A lot of mature businesses underestimate the depth of the digital transformation and the amount of time it will take for a large business to integrate the dynamics of digital with the rest of the business. Digital startups can work agilely naturally—because they are small. Mature businesses have to work at being agile—and then make the transformation.

After a digital conservative leadership with a healthy cash reserve finally figures out that their business is in trouble, it’s often too late for them to make the changes required to remain competitive.

Reason Three: We’re Too Profitable to Fail

In an environment where profit is adequate to satisfy executives and shareholders, there is often little incentive to improve anything because the business is profitable enough. Why rock the boat when the sea is calm? Not unlike organizations that see themselves as too important to fail, some businesses see the immediate integrity of the balance sheet as an indicator that digital has not yet hit their market sector. Or, more strongly, that digital may be irrelevant to their marketspace.

I often have conversations with digital workers who state that there are executives in their organization who are still skeptical about the value of digital for anything more than creating digital brochure-wear. To the executive’s defense, it is true that digital has disrupted different vertical markets in different ways and at different paces, but complete inattention to digital governance and performance is a mistake. The disruption of digital is too broad, deep, and complex to be disregarded on the whole. Depending on the reality of digital disruption, the stance of being largely bulletproof to digital disruption might be spot-on, or more likely, it might be management hubris that will lead to the downfall of your business.

Even if your organization might be bulletproof to digital disruption at the moment, at the very least, any organization needs to govern digital well enough so that it is in compliance with regulatory concerns and able to uphold the integrity of the brand online through the implementation and support of basic quality standards. From a more strategic perspective, every organization has a responsibility to monitor the impact of digital on its market so that it is poised to be more proactive about digital development if and when market impact begins to show itself in substantive ways.

Reason Four: Difficult People

Occasionally, staff in an organization doesn’t want to point to governance problems because the cause of the governance problem includes a powerful or influential business unit. The power of the group or individual can be derived from a variety of sources, including their ability to deliver revenue to the company’s bottom line, their social or business proximity to a key executive, or their tenure and legacy organizational knowledge. Digital workers are sometimes reluctant to run counter to these resources. So, instead of pointing out how a particular digital stakeholder’s behavior is impacting the business in a negative way, they remain silent in order to remain non-confrontational (or in some instances to keep their jobs).

It takes a substantive amount of managerial courage to manage through a negative organizational management gauntlet. As I mentioned in Chapter 2, “Your Digital Team: Where They Are and What They Do,” often digital workers aren’t offered the same sorts of managerial development opportunities as other employees, so sometimes they just don’t know how to deal with powerful and contentious managers and individual contributors. Even when digital workers are equipped with appropriate negotiation skills, it can still be a tough battle. I’ve heard many stories of digital workers going to management with solid metrics and evidenced-based stories of digital failure, risk, and opportunity and being all but ignored by senior and executive level managers. In a few rare instances, the digital workers have even been penalized for stepping “out of bounds.”

How much vocational risk a worker wants to assume is a matter of personal choice. But sometimes these “politics” can be so strong that any efforts at formalizing digital governance or otherwise maturing digital can be very challenging. This is a tough situation for employees by all measures, but it’s important to understand the dynamic and to recognize it for what it is. Once identified, these human resource-related concerns really aren’t as complex as they appear, and a solution can be crafted. But sometimes the situations can be very challenging, and given the existing dynamics, a digital worker might decide that it’s not worth taking the vocational risk and that, in extreme cases, in order to continue growing a career, that person might need to move on to another organization.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DO: Remember that any organization can be unexpectedly impacted by digital disruption. Digital executives need to be vigilant and prepared to address that impact when it occurs.

Moving Forward in Less Than Ideal Circumstances

On the whole, the less-than-optimal dynamics described earlier contribute to the deep frustration of many digital workers. Not just because it denies them their rightful place at the governance table, but because it minimizes digital workers’ expertise and often relegates their role to one of a production-focused Web page “putter-upper.” It ignores the reality that frequently digital workers are the first people to see new ways for their organization to leverage the Internet and Web. Because digital workers have a forward viewpoint on an emerging market technology space, digital workers are often the first to understand where the organization’s market share or brand is eroding due to low digital quality, and they are the first to see where there might be an opportunity to innovate and create with a competitive advantage.

Personally, I sometimes find it frustrating to work with digital teams in organizations where that expertise is being stifled due to a lack of clarity around digital governance. It seems like a tremendous waste of organizational knowledge. In reality, many digital workers are eager to share their knowledge and contribute in a substantive way to the organization’s bottom line—if only they were given the chance. So, given this reality, how does a digital worker help an organization move forward with digital governance? Let’s take a look.

In situations where organizations do not see the value in formally governing digital, there are a few tactics that can work to break through the gridlock and jump-start a digital governance effort—or allow you to more effectively manage digital while you’re working on the governance model. They are as follows:

• Aligning internal digital resources

• Quantifying the risk of a low-quality “ungoverned” digital presence

• Quantifying and promoting the upside of digital

All of these tactics should be prominent in the context of a formalized digital governance framework, but they are not a complete replacement for a well-implemented digital governance framework. However, if you’re faced with a situation where you are unable to illicit sponsorship from executives, these tactics can help mitigate some of the operational risks associated with immature digital governance. And these tactics will often point the organization in the right direction, as some of these behaviors can illuminate the value of digital governance to the organization.

Internal Alignment

It is good to see three different levels of alignment around digital in an organization: one at the senior management or executive level, one at the middle management level, and one at the practitioner level. In large organizations, that alignment can effectively fall into these groups:

• Executive: Digital steering committee

• Core digital team: Center of excellence

• Digital practitioners: Community of practice

Your organizational may not choose to use these names, but here is a description of the functions they serve.

Digital Steering Committee

This team is responsible for establishing digital strategy and ensuring that what happens online is in harmony with the company’s business objectives. In the formal framework, these people would be your digital strategy decision-makers. In the absence of a formal digital governance framework, it’s still possible to bring senior resources together to help steer the general direction of digital. If you are junior to these resources, pulling this team together might be a challenge. An effective tactic in this instance might be to propose the inclusion of the digital strategy agenda to an already existing cross-functional management committee or working group—such as an executive team or a global MarCom strategic group. Effective results can be achieved by introducing a digital agenda to these sorts of teams on a quarterly basis.

If your senior digital team members are fortunate enough to engage leaders at this level, make sure that when you’ve got your moment on their agenda you focus on how better digital governance and online quality can add value to the business by enhancing revenue and mitigating risks. Sometimes when digital workers get the opportunity to speak with senior leaders, they flounder by discussing the tactics of a technology selection, content strategy, or the like. That work is important, but it does not need to be discussed at this executive level. Executives assume that their employees (and that includes digital workers) know how to get their work done. What they need to know from senior digital team members is how they should enable digital efforts through the commitment of fiscal or human resources. But before they make that commitment, they are going to want to hear a business case, not a talk on digital best practices. Engaging executives in this way often makes the case for a more formal effort in digital governance, especially when the opportunity and risk aspects of improving digital are emphasized.

Digital Center of Excellence

A digital center of excellence can be established, absent a formal digital governance framework. The center of excellence is a hub populated by domain experts who can inform standards and advise other organizational practitioners. They also align digital with the rest of the business so that they can inform management about the business value of a more orchestrated approach to digital governance. In many instances, effective core digital teams are able to boost their profile and authority by honing their expertise and “upping their game” in the organization and informally stepping into this role. In this manner, the core digital team can become the de facto digital leads in an organization.

Naturally, this course has its limitations. Those people outside of the center of excellence can still refuse to comply with best practices as outlined by this team. But 80 percent compliance to an established set of best practices is better than no common core of best practices and guidelines. When the core team sharpens its leadership skills, models best practices, and learns to speak the language of business, usually the team will find that executives who had not considered digital to be a strategic asset for the business in the past will have a change of heart now.

Digital Community of Practice

Establishing a digital community of practice inside the organization is an effective way to align all the tactical resources working on your digital presence. A community of practice is a collaborative forum with open membership. The agenda of a digital community of practice varies, but often it is leveraged to do the following:

• Pilot various digital initiatives, which substantively demonstrate a more orchestrated approach to digital development.

• Establish a forum in which to discuss and come into alignment around differences related to policy, standards, and guidelines.

• Provide an environment for training digital resources on new technologies and digital practices.

• Keep digital resources connected and in basic collaboration while an organization seeks to establish a more formal governance framework.

The digital core team plays a key role in the establishment of communities of practice. But, in this informal community, it should be careful not to adopt an attitude of “do what I say,” but instead to create an environment where everyone’s opinions are heard, and true discussion and open debate can happen. These grassroots communities, when well run, can begin to align a global digital team that is out of sync.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Forget that digital governance framework implementation involves realigning human resources—that’s different than redesigning user interfaces or implementing a technology stack. It’s harder and less predictable.

Also, alignment at the grassroots level is an effective way to demonstrate to senior leadership the power behind the unified approach to digital. While more junior resources in the organizations may not be able to give themselves the authority to move or increase the digital budget and head count in an organization, they can certainly begin to come to consensus around digital quality guidelines and present a unified front to management. There is nothing more powerful than a well-organized, good functioning cross-functional team going to executives with a unified supported request for resources. That request could be for technology, head count, or for the executives to provide digital workers with the strategic guidance they need to truly take digital governance and operations in the organization to maturity.

Quantify the Risk

As I mentioned in the first chapter, sometimes organizations are so used to working the way they do that they don’t understand that they are operating under substantial risk. Even 20 years into the commercial Web, digital channels are still relatively new to most organizations, and while there are emerging best practices and norms, very few digital processes can lead to a guaranteed business result. So the objective value of digital to organizations, particularly those that do not have an obvious upside from digital (like ecommerce driven and other B-to-C businesses), is sometimes difficult to express, as is the risk associated with not doing things the “right way.” Despite this nebulous state, quantifying risk associated with poor digital operations and governance is not impossible, and it is a key tactic for raising concerns to senior management and executives in your organization.

When you raise risks to executives, be certain that they are substantiated with metrics. Also, make sure that the substantiation is relevant to your business. That means talking about the risk of non-compliance with accessibility standards is probably relevant to a governmental organization but less relevant to some B-to-B type organizations that do not have a legal requirement to comply with certain accessibility standards. Of course, the organization still might want to comply with those standards, but if it doesn’t comply, it’s not a risk (unless there is a cultural/brand risk, which could be minimized by adherence to these standards).

Another example might involve ensuring that individual customer data is handled properly online and offline. Digital has been thrown into the mix of many organizations so quickly that often they are unable to come keep track of how certain applications interact with other applications. Standards related to tracking, cookies, data management, and other privacy concerns are crucial. Yet in a decentralized digital management environment where a lot of unmanaged organic digital growth has occurred, organizations may find themselves unintentionally out of compliance. Again, this lack of compliance is not willful. It’s almost accidental. However, “we didn’t mean to do it” is not an effective excuse in a court of law.

Digital workers also get caught up in the correct way of doing things according to best practices. This is admirable and sometimes relevant to the business. But it’s important to pick your battles. If you look around your organization, you will see that there are processes that are well done and others that are little bit looser and may not adhere to best practices. This is normal in an organization. While you always want to strive toward excellence, there are aspects of digital that are really well done and other aspects that may be not so well done. It’s important for you to understand what parts you must execute upon well. From a risk perspective, those would be the policies and standards that will keep your business in alignment with the law and well positioned for profitability in your market sector.

If you are trying to challenge executives to fund additional governance initiatives or better fund digital overall, a short business argument supported by three solid but remarkable metrics is much more powerful than trying to tell the entire story of quality digital. To be honest, most executives don’t want to hear tactics related to that story.

DO’S AND DON’TS

DON’T: Give up, just because you can’t find an executive advocate for governance. There are things you can do at the grass roots level in working groups that will start to foster alignment until the executives come into alignment.

Emphasize the Business Opportunity

Many digital experts are passionate about the work they do—whether that’s user-centered design, application design and development, content strategy, or mobile development. There is a right way to go about creating an effective digital presence, and digital workers understand all the details of that. But, and this might be a tough pill to swallow, often management just doesn’t care about the “right way” to do something. Management wants to know how what you are proposing is going to provide quantifiable value to the organization.

I once heard Information Architecture guru Peter Morville say that executives speak in business haiku, and it’s true. Executives have to be able to understand the full breadth of the business, and in order to do that, the information has to be highly distilled. Digital workers aren’t always the best at distilling information. They come at their peers and managers with jargon they can’t understand, spreadsheets of content, ethical diagrams, and the like. If you want executives to invest time in understanding digital, you need to take the time to understand the world of executives, which often focuses on quantifiable results. At best, you can explain how improved digital governance will help impact the bottom line, and if your executive suite isn’t ready to hear that story, at the very least you can make sure that your own digital house is in order.

Making Your Order Out of Your Chaos

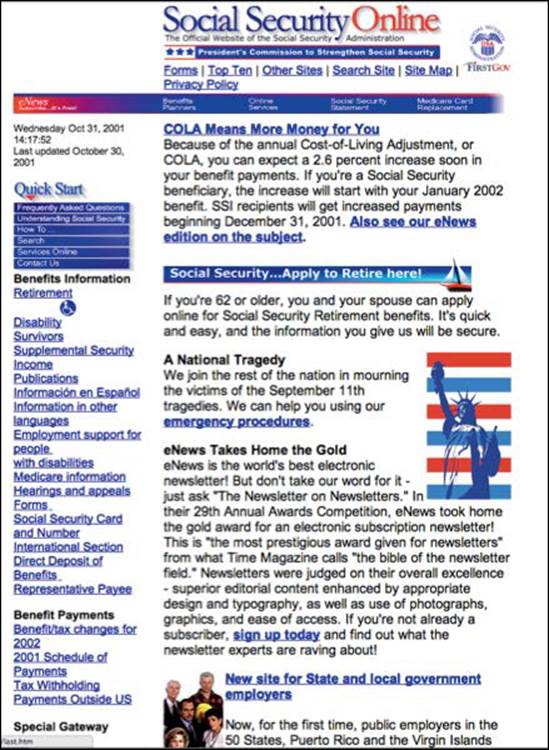

The first few governance projects that I worked on in the early 2000s included the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), as shown in Figures 8.1 and 8.2. Both organizations had sharp Web teams. Both organizations came pretty early to the Web, and both teams were early in realizing that they had governance concerns. But the underlying dynamics of the teams were very different. At the SSA, the website had some information architecture problems, needed a new content management system, and with hindsight, probably some serious content strategy work needed to be done—the site was full of redundant, outdated, and trial (ROT) content. But the SSA’s key Web manager for the public website had made a decision at the onset of digital development at the agency, which was that almost all content changes would go through his team. Technology choice decisions were also strongly centralized.

The EPA pretty much had the same set of website problems as the SSA—except more—hundreds of thousands of pages more. The site was many orders of magnitude bigger than the SSA’s site. Organizationally, the EPA had (and still has) a strong “office” component (The Office of Air, The Office of Water, The Office of Solid Waste, and so on), and their digital story included office-focused distributed content, contribution rights, and technology implementation. The distribution was so complete that digital stakeholders often spoke as if those offices had completely different websites.

So the SSA had a biggish website directed mainly by a few resources, and the EPA had a huge website directed and informed by over 30 key players. Which team, do you think, had an easier time implementing governance and subsequently implementing their desired website changes? If you guessed SSA, you’d be right.

The point isn’t that EPA was “wrong” and SSA was “right.” The point is to illustrate that small decisions and dynamics made early in the development of a process will seriously impact a future outcome. It’s the famous “Butterfly Effect” (see note: “The Butterfly Effect”). It’s like drawing two sets of lines emanating from the same point, but pairing one at a 90-degree angle and the other at a 91-degree angle. If it were a short line, maybe there wouldn’t be much of a difference. But if the lines were a mile long, the difference between the two lines would vary greatly from pair to pair.

In the SSA/EPA cases, the decision to centralize many governance-related decision-making functions and a lot of production to a core administrative team meant that years later the SSA had much more control over resources when it wanted to make changes. EPA was in an environment where those same choices didn’t make organizational sense at conception (or simply just didn’t happen), and 10 years later, they were in a completely different place regarding their ability to govern and implement website-wide change. Little things can make a big difference when you add the components of time and scale. When there are a lot of choices made that aren’t documented or understood, the situation could look chaotic.

FIGURE 8.1

Social Security Administration website at the turn of the century.

FIGURE 8.2

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website at the turn of the century.

NOTE THE BUTTERFLY EFFECT

When the present determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.

Edward Lorenz (1917 – 2008)

For every organization, there have been many early decisions made about how to govern and manage digital, and those decisions have created the unique work patterns and structures that exist in your organization and online today. Every organization has a unique set of digital governance design challenges, which is why you can’t skip steps. If you haven’t taken the time to intentionally think about the dynamics of digital strategy, policy, standards, and digital team functions, then it will be hard to design a solid digital governance framework.

The shortcuts outlined in this chapter are helpful, but there is no substitute for the real thing. So, if you’ve skipped forward to this chapter, go back. It’s important to do the work. It will make a difference. Unfortunately, you can’t change the early dynamics of how digital was started in your organization, but you can understand them well now and begin to influence the future direction of digital. You can start the journey of navigating through your organization’s unique digital chaos. You will find a way, and digital governance will improve within your organization.

Summary

• Organizations must make a conscious decision to govern well. Sometimes in order to avoid the hard work of digital, governance organizations come up with complex reasons why they cannot improve digital governing dynamics. But these dynamics are seldom the real cause for the lack of interest in digital governance. The real reasons are related to the following:

• Not wanting to change existing work dynamics.

• Thinking the brand is too important to fail.

• Believing that the organization’s profitability renders it bulletproof to the impact of digital.

• Difficult people using power to make sure that the digital governance chips stay on their side of the table.

• In organizations where there is no executive support to improve digital governance, there are a few tactics that can be effective in helping improve digital operations: aligning internal digital resources at the executive, management, and digital practitioner levels of the organization; quantifying the risk of an ungoverned online presence to executives; and detailing the opportunity associated with better digital quality.

• A lot of organizations are in digital chaos, but the path they took to get to that chaos is unique. Therefore, the solution for normalizing and maturing digital governance and operations will also be unique.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.