Managing Chaos: Digital Governance by Design (2015)

PART II

Case Studies

The following are outlines of digital governance frameworks derived from projects I’ve worked on with clients over the past 10 years. I’ve combined and tweaked here and there to normalize the format of the recommendations (obviously, different organizations have different documentation needs) and to keep certain organizational and background information confidential. On the whole, though, they are realistic representations of some of the outcomes you can expect when designing your own framework.

CHAPTER 9

![]()

Multinational Business-to-Business Case Study

Pre-Framework Dynamics

Our Overall Framework Recommendation

Digital Team Findings and Recommendations

Digital Strategy/Governance Advocacy Findings and Recommendations

Digital Policy Findings and Recommendations

Digital Standards Findings and Recommendations

After the Framework Definition

The “last straw” event that led this multinational business-to-business (B-to-B) organization to address digital governance was a content emergency related to inappropriate content on live websites. In trying to react to address the content concern, the executive team in the organization (20K+ employees globally) realized that there was little oversight of websites and other digital channels globally. In particular, they didn’t know how many websites and social channels were being managed and moderated by the organization. There was also a general inconsistency with the quality of the content on different product and country websites. The amount of redundant, outdated, and trivial content (ROT) on the website was high, since no one had taken the opportunity to consider the full lifecycle processes for managing website content. Consequently, information was being put online and left there—for years—with no plan for maintenance or retirement of content.

This emergency led to the executive team telling the Web team to “figure it out” and come up with a content strategy and governance model. The core Web team was highly competent—one of the sharpest teams we’ve ever worked with. The team was already aware that there were global digital abnormalities and a lack of governance, but had never been given a clear mandate or resources to implement policy or standards for any of the other websites globally, and they lacked the bandwidth to create a framework before the crisis occurred. When we arrived, they had already performed a content audit and worked with IT to create an inventory of websites and social channels. They wanted us to help them design a governance framework with an emphasis on addressing the differing management and governance needs of various country-focused websites and their support staff.

Because of the content-centered focus of this engagement, we included a content strategist on our team to make recommendations about the organization’s global content strategy as well. The company had over 20 country-specific Web and social channels that supported a number of product lines. The work of the content strategist allowed us to make deeper than usual recommendations in the arena of digital governance.

Pre-Framework Dynamics

The core digital team was frustrated that it had taken this emergency engagement to bring issues to the forefront, because they had been attempting to communicate the less positive aspects of organizational digital governance to senior management and the executive team for some time.

As we dove into our discovery process, we realized that the call for digital governance was a superficial one. In reality, the executives just wanted the website mess cleaned up. They weren’t truly interested in figuring out ways to integrate digital into the business in more sophisticated ways. Here were the facts in this organization:

• Governance was perceived as solely an operational concern, not a strategic one.

• Profitability was high enough that the “upside” of digital was perceived as speculative and not an obvious channel for business opportunity.

• Funding the core team to bring more domain expertise was not likely to be a supported part of the solution. “We can’t get more headcount.”

• There was a high sense of geographical and brand autonomy while at the same time, given regulatory constraints around content, there was not, for the most part, a Wild-West type, do-your-own-thing mentality about digital content, applications, and transactions. The higher risk for the organization was outdated, inaccurate content due to inattention and lack of strategy around content both globally and locally.

• Content needs differed from region to region, but that fact had not been taken into consideration.

These dynamics left the core digital team somewhat frustrated because they saw that there was a real opportunity for the business to become more competitive via better use of content, social software interactions, and mobile applications in the organization.

Our Overall Framework Recommendation

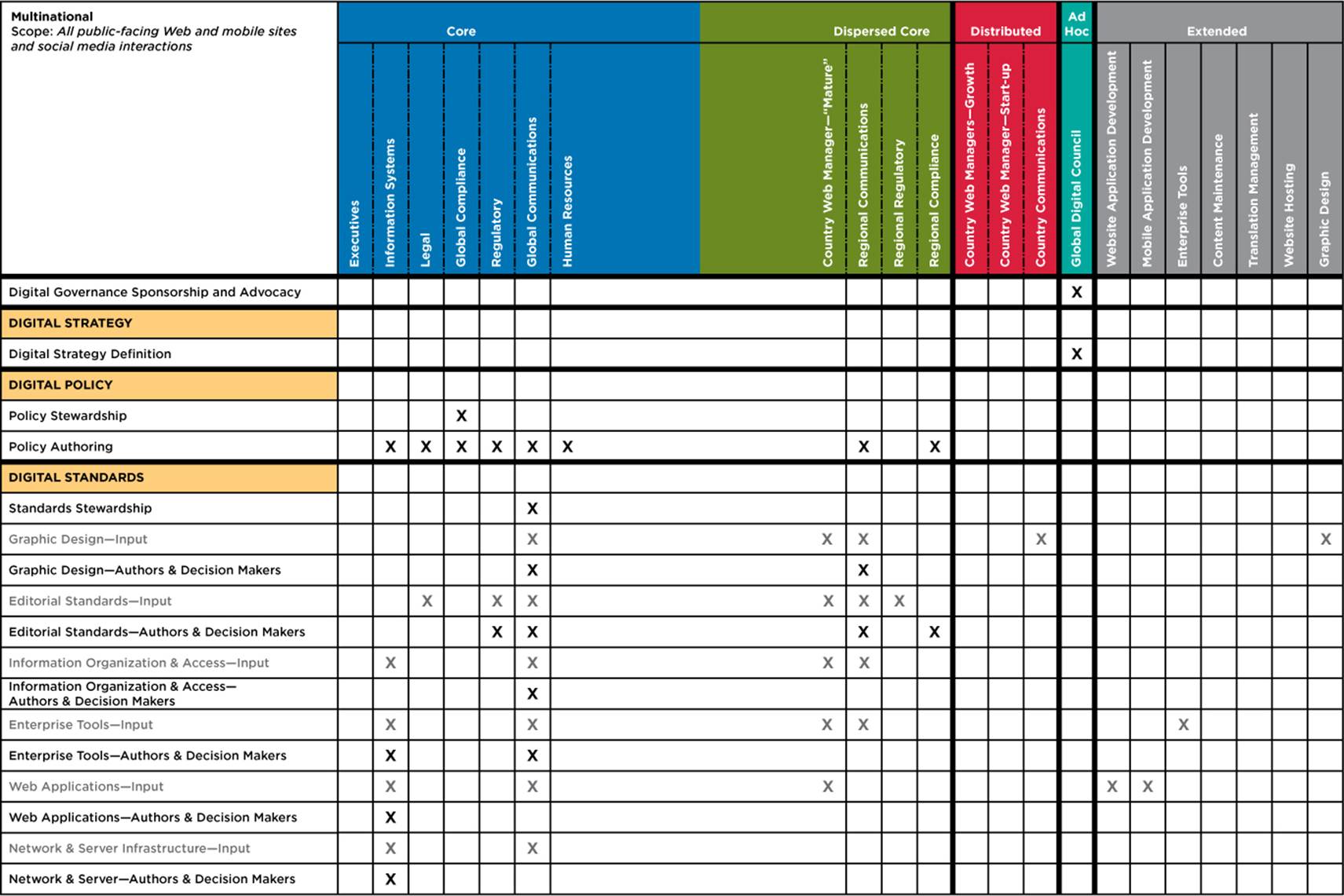

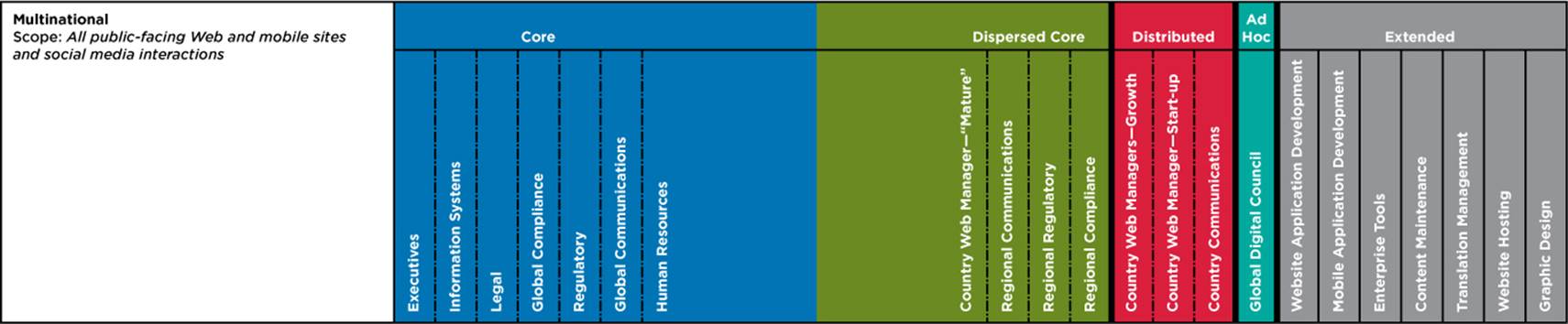

Given some hard constraints placed on the governance solution (“no new headcount” and some unbreakable long-term contracts with external vendors), there were limits to the solutions that we could offer. However, we were able to raise the visibility of some content concerns at various locations and recommend a more nuanced Web team model, as shown in Figure 9.1.

FIGURE 9.1

Proposed B-to-B governance framework.

Digital Team Findings and Recommendations

This organization had an array of resources working with its digital presence globally. The core team was rather sharply defined, but as we moved from the core to the outer reaches of the team, there was a lack of definition, as well as a lack of alignment with the local work at hand—particularly as it related to content development. Overall, we saw that the following circumstances were in place:

• The global digital team was ill defined, which led to poor quality in the content. Some sites had no Web manager of record and had not been updated for over 12 months. Some websites were simply “dead.”

• There were loose digital development processes that were out-of-sync with industry-related compliance demands. Some content was on servers that had not been properly reviewed, or the content was outdated, which was an increasing risk to the organization.

• There were a large number of support vendors globally, but the lack of a set of codified and implemented standards did not allow for editorial consistency globally.

• Despite the increased use of digital, senior management refused to add additional headcount to the core and distributed teams in most cases.

FIGURE 9.2

Digital team structure.

Our primary goal was to ensure that the digital team (see Figure 9.2) was staffed with subject matter experts who could effectively support the range of digital activities at the organization. Just as the website had grown organically, so had the team, and there was a lack of balance in the team that led directly to low user experience, especially as it related to online content.

Initially, we recommended that the organization add two additional headcount that would focus on translation management and content strategy, but this recommendation was rejected. We subsequently recommended that the organization support these activities with external vendors and via capital expenditures (instead of additional headcount).

The Core Team

The core digital team was tasked with overall guidance and direction for Web development and to ensure that the B-to-B Web presence was supported by enabling content and technical infrastructure. This team was also responsible for orchestrating all Web development processes and reporting on the effectiveness of the Web for the organization. The core digital team was placed in the Global (corporate) Communications department with technical implementation support from the Information Services teams.

The Dispersed Core and Distributed Team

Due in large part to this B-to-B’s varying business maturity and goals in various locales, different country websites had different needs online. Therefore, Web production practices and governing dynamics (like some policy and standards) needed to differ from country to country. So we needed to add a dispersed core Web team component to the framework. In particular, the dispersed core had to have accountability for some policy and standards definitions that were best defined locally.

Also, to support differing business needs, we recommended three different country Web team models within the dispersed core. One model would support countries in a “start-up” mode, another model for those in “growth” mode, and a third model for countries where B-to-B’s communications, business, and sales objectives were “mature.”

Start-Up

There were nine candidate countries for this category. This segment addressed digital efforts that were supporting an emerging market or a new acquisition with a light digital footprint. The core team responsibilities (governing and product-related) included the following.

Governing Responsibilities

• Global communications manager to support Web development with support from external corporate vendor of record.

• Support production-related responsibilities.

• Localize Web content when required.

• Maintain Web content within a content management system. B-to-B will provide access to resources fluent in target language who can maintain content in the CMS.

• Participate in global Web community training and networking.

Growth

There were eight candidate countries for this category. This segment addressed digital efforts for new acquisitions with a pre-existing substantive local footprint. The core team responsibilities (governing and product-related) included the following.

Governing Responsibilities

• Articulate content strategy.

• Document and clear localized Web standards with local regulatory team when they differ from corporate standards.

• Identify process for publishing and maintaining content.

• Appoint a dedicated Web manager resource or an active, non-dedicated communications manager.

• When in use, appoint a designated social media manager.

• Have a local Web budget to support country Web page development.

Production-Related Responsibilities

• Localize Web content when required.

• Maintain Web content within a content management system.

• Participate in global Web community training and networking.

• Update content monthly.

Mature

There were 10 candidate countries for this category, and they were candidates that had an established or strategically significant market for the company. Their core team responsibilities (governing and product-related) included the following.

Governing Responsibilities

• Localize Web budget to support country Web page development.

• Articulate content strategy.

• Define and integrate local translation management processes with the corporate Web team.

• Identify process for publishing and maintaining content.

• Document and clear localized Web standards with local regulatory team when they differ from corporate standards.

• When in use, appoint a designated social media manager.

• Appoint a dedicated Web manager resource.

Production-Related Responsibilities

• Localize Web content when required.

• Maintain Web content within B-to-B’s content management system.

• Participate in global Web community training and networking.

• Update sites at least weekly.

Working Groups and Councils

There was already an established global digital council that would remain functional with the following key stakeholders:

• Regional communications managers

• Regional IT managers

• Regional business executives

Extended Team

The core team was supported by vendors who specialized in the following areas:

• Application development (website and mobile)

• Enterprise tools

• Graphic design

• Content maintenance

• Translation management (for Web)

• Website hosting

Digital Strategy/Governance Advocacy Findings and Recommendations

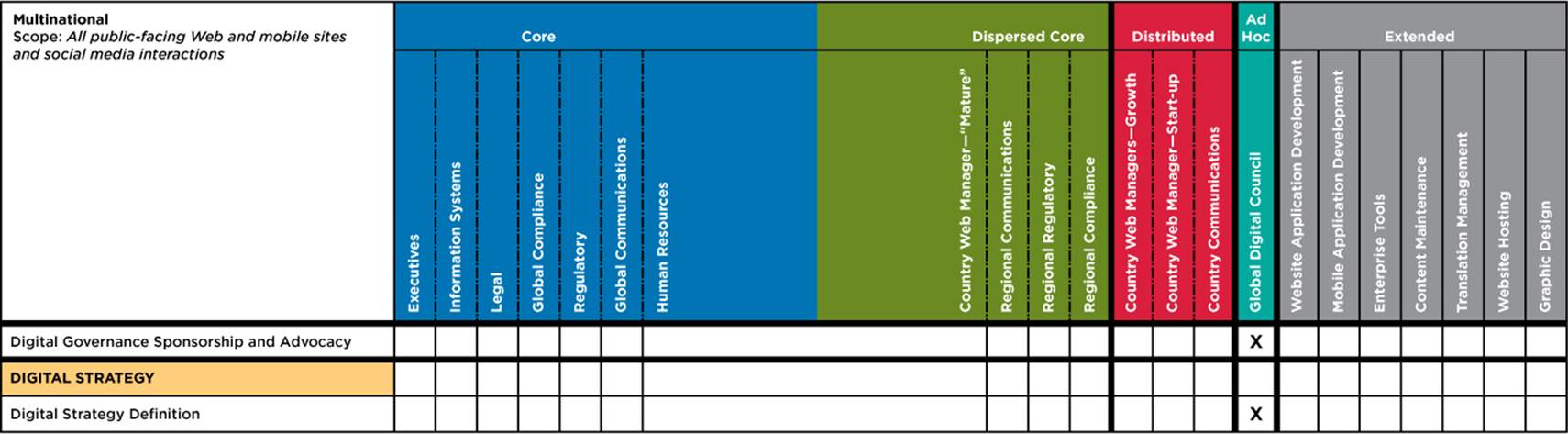

Digital strategy and the advocacy for deeper digital maturity were a challenge for this organization. The executives were definitely “digital conservatives,” and when we left this engagement, the core team was still challenged to raise the business opportunity of digital to the executive level.

This business case for digital did not touch on the core aspects of the business model, and the somewhat sophisticated metrics that would have been required to make a business case were not at hand, nor did the core team have the bandwidth to establish those metrics. Therefore, everyone was focused on moving into the basic management phase of digital maturity, which involved understanding where their website and social channels were and who was managing them. Although they were able to better align the digital team to a set of guiding principles by the time we left, we felt that they were still not in an ideal situation. The key points of our observations were the following:

• They had a weak organizational Web strategy that was focused solely on the top-level corporate website and was driven by the Web team, not the organization at large.

• Executives were disengaged from digital unless there were “emergency” issues.

• There was a lack of alignment between the business reality and what was happening online. For example, the business had a mature and growing market with certain geographical regions, but at the same time, they were reducing the resources required to support the digital presence in that region.

Digital Strategy Accountability

We suggested that a Global Digital Council be established to serve as an advocate for deepening and maturing digital governance (see Figure 9.3). We advised that that this council should include in its charter the articulation of guiding principles and Web performance measures for Web development.

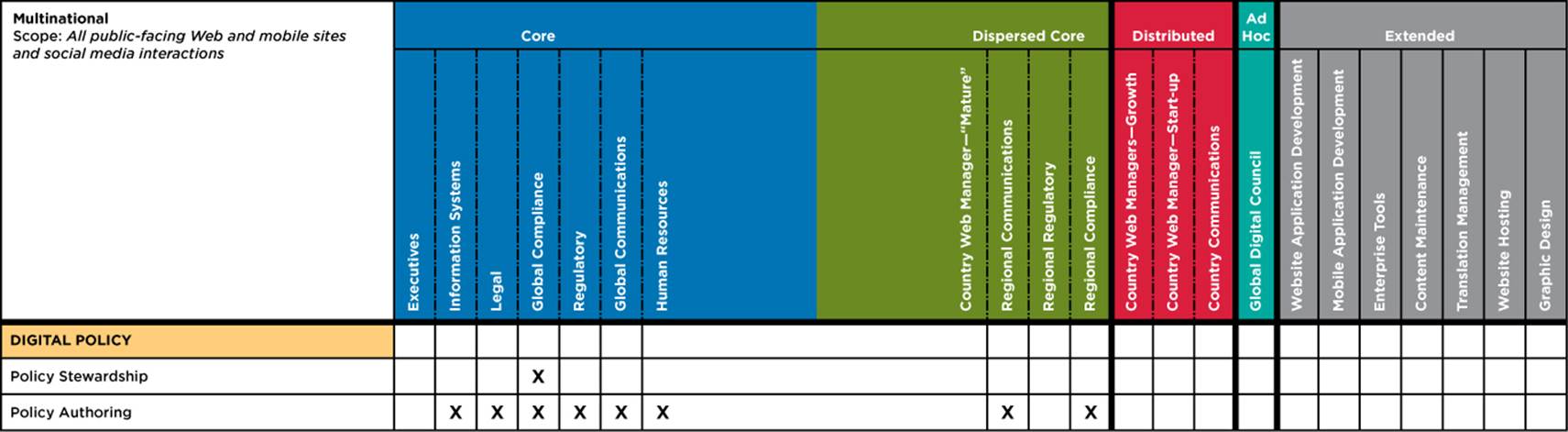

Digital Policy Findings and Recommendations

Given the highly regulated marketspace of this organization, digital policies did exist. However, there were weaknesses to address at the regional levels globally, which included the following:

• The digital policy stewardship was unclear.

• There was a strong corporate policy, but the digital policy concerns were not as well localized to address localized policy concerns and regulatory needs.

We recommended that policy stewardship be the responsibility of corporate compliance (see Figure 9.4). This team would assign authorship as required to regional communications staff and regional compliance officers (see Figure 9.5).

FIGURE 9.3

Accountability for digital strategy.

FIGURE 9.4

Accountability for digital policy.

|

Policy |

Author |

|

Accessibility |

Global Communications Information Systems |

|

Branding |

Global Communications |

|

Data |

Information Systems |

|

Domain Names |

Information Systems |

|

Editorial |

Global Communications Regulatory |

|

Email Addresses |

Information Systems |

|

Information Management |

Global Communications Information Systems |

|

Intellectual Property Protection |

Compliance Legal Global Communications |

|

Language & Localization |

Global Communications Regulatory |

|

Hyperlinks & Hyperlinking |

Global Communications Regulatory |

|

Privacy |

Legal Compliance Regulatory |

|

Security |

Information Systems |

|

Social Media |

Global Communications Regulatory Human Resources |

|

Web Records Management |

Global Communications Regulatory |

FIGURE 9.5

Policy authors.

Digital Standards Findings and Recommendations

This team knew that it had deficits in the area of digital standards. We wanted to help them focus on keeping standards compliance higher through clearer definition and management of the standards lifecycle. The top-level findings for this company were:

• The core digital team members were de facto stewards for corporate standards related to main business brand websites and social channels.

• The standards stewardship for distributed Web teams and websites was unclear.

• The documentation of standards was uneven with particular weaknesses with regard to information organization and access and application standards.

The corporate Web team within global communications was accountable for ensuring that all Web standards were documented and available for stakeholders to consult. The corporate Web team was also responsible for ensuring that infrastructure tools and processes were architected to support standards compliance. Finally, the corporate team was tasked to support the enforcement of Web standards by measuring and reporting compliance to standards on a quarterly basis.

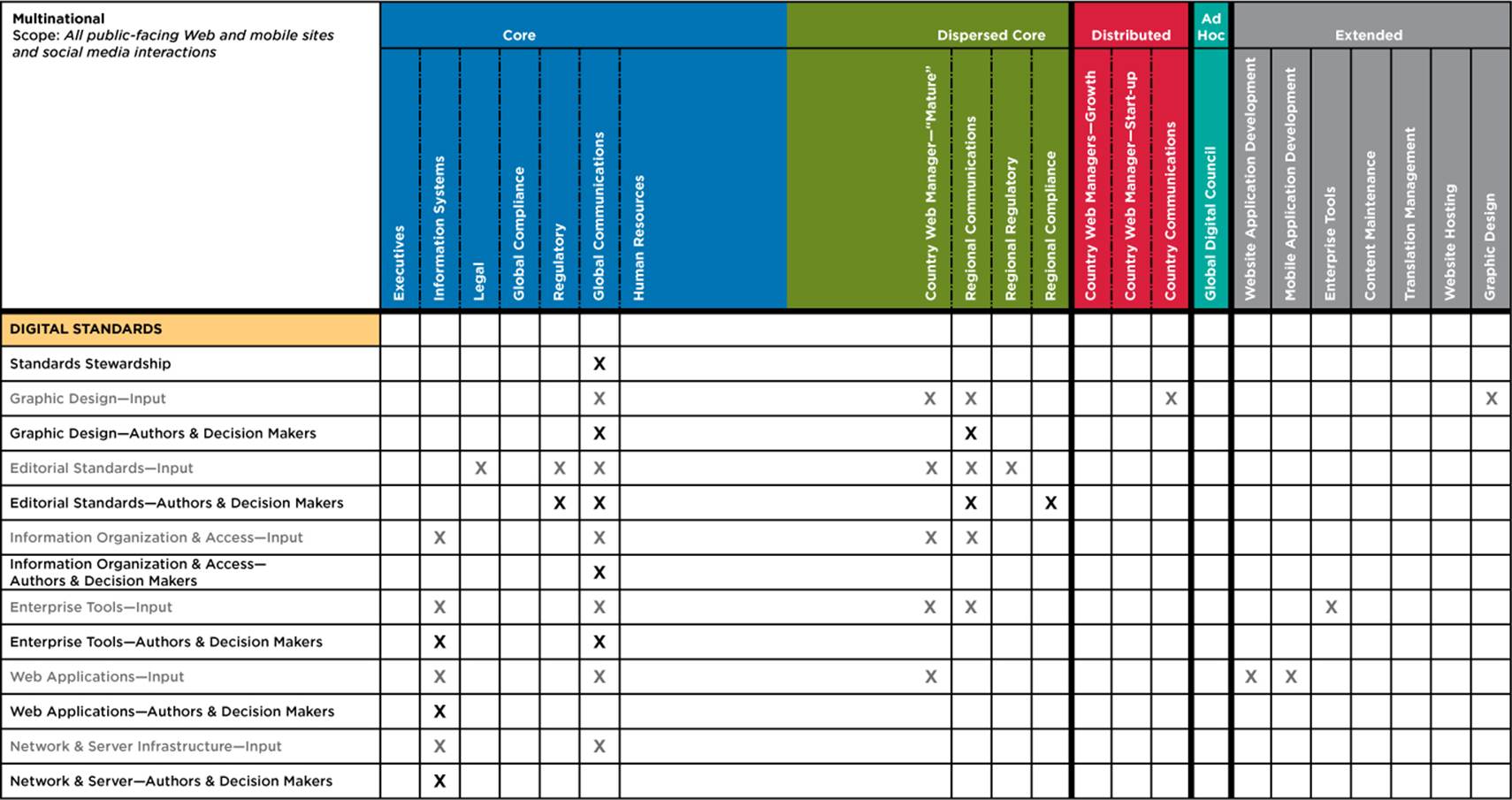

Standards Input and Decision-Making

There was a high level of autonomy in this organization, so it was important to make clear how and when certain digital stakeholders would be able to provide input for certain standards. We included that level of detail in their framework summary (see Figure 9.6). Also, this team chose to be more granular about its standards areas than the four standards categories we generally outline within a framework.

After the Framework Definition

Fortunately, this team was able to informally implement its digital governance framework; however, they were not able to get the top-down executive support necessary for an across-the-board transformation that the core team desired. The upside of this situation was that all of the stakeholders were happy, for the most part, to comply with the standards as outlined by the standards “owners.” Processes were tighter, and policy definition and compliance processes were much sharper, which was an essential component in this highly regulated environment. The executives were happy once the content emergency was managed.

We would have liked to have seen a more strategic engagement. But this company was doing well, and until there was an obvious disruption for the organization, it was going to be unlikely that digital would be pushed in a more strategic direction. This team is now well settled in the “basic management” stage of digital governance. And that’s okay.

FIGURE 9.6

Standards accountability.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2025 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.