Understanding Context: Environment, Language, and Information Architecture (2014)

Part V. The Maps We Live In

Chapter 16. Mapping and Placemaking

There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.

—JANE JACOBS

Maps and Territory

INFORMATION ARCHITECTURE IS LARGELY CONCERNED WITH BOTH DESCRIBING AND INSTANTIATING NEW PLACES, but these places are made largely of semantic information. Mapping is a method that people have invented to establish context, using semantic information for the task. Sometimes, maps describe something that isn’t made yet. Often they describe something that already exists but is too big or complicated on its own. A map is a semantic-information artifact that helps us understand something about what it describes, even when it is describing itself.

This puts an interesting twist on how we normally think of maps and their relation to places. From one position, we can say that maps and the places they describe are not the same things, but from another position, maps are hard to separate from the places they are about, and they change what those places mean to us.

So, let’s begin with the first position: “The map is not the territory.” Those are the words of Alfred Korzybski, the philosopher and scientist who developed the theory of general semantics. Korzybski wasn’t especially writing about cartography; his main point was that the concepts—and language—we use for the world aren’t the same as the world itself; we need to realize that the way we describe the world can become reified so that it colors and constrains our factual understanding of it. Cultivating this perspective requires an explicit, deliberate effort that is necessary especially in the sciences, where empirical fact can sometimes be obscured or warped by our cognitive biases.

Of course, it’s important to cultivate this perspective in design, as well. One reason why user experience design relies so heavily on research is that the approach acknowledges we have to get out of our own assumptions—our own “maps”—to better understand the “territory” of actual user behavior.

Then, there’s the second position: in some ways, the map and territory are the same. Sure, a map is not literally the same as the dirt, concrete, and steel that make up the actual, physical territory, but we don’t experience the world only as physical territory—we experience it in terms of places, which are as much cultural and linguistic for humans as they are physical. People use the full environment, maps and all; they don’t go about their day analyzing how the map and territory are separate. They satisfice and conflate; they take tacit action and concentrate only when necessary.

Writing about cartography and the cultural function of maps, Edward Rothstein explains:

By suggesting that all understanding may be a form of mapping, it turns maps into an archetypal example of human knowledge. Indeed, in discussing thoughts or feelings, people often invoke a cartographic universe. Feeling bewildered, one talks about ‘’terra incognita,’’ about ‘’being at a crossroads’’ or ‘’losing our way.’’ Gaining understanding, one speaks of ‘’putting things in perspective’’ and ‘’being on familiar terrain.’’ People come to know the world the way they come to map it—through their perceptions of how its elements are connected and of how they should move among them.[302]

Mapping is action toward understanding. This natural tendency to merge map and territory is what prompted Korzybski to coin his aphorism in the first place; he intended it as corrective advice. Realistically, we can’t expect the people who use the environments we design to analyze them like general semanticists or research scientists. In terms of real human perception and action, the map and the territory are inseparable.

What Makes Places

Maps are complex semantic artifacts we use to understand context and place, which means they participate in the activity of placemaking—a term with many related meanings, from many different disciplines. In this discussion, we’re going to use the term as shorthand for two things at once:

§ The ecological dynamic James J. Gibson describes between the environment and the perceiver—the organic, emergent sort of placemaking that happens even in nature.

§ The intentional design of an environment to be perceived and used as one sort of place versus another; in the terms of information architecture, placemaking is a heuristic described as that which helps “users reduce disorientation, build a sense of place, and increase legibility and wayfinding across digital, physical, and cross-channel environments.”[303]

Recall Gibson’s elements: place is a function of the relationship between an agent and the layout of its environment, and a place is a place only because it affords meaningful action. Places don’t necessarily have solid boundaries, though artificially built environments might establish those more explicitly. We can create structures that we intend to be perceived as places, but it’s up to the perceiver to find meaning in those structures that resonate as “place.” I walk by buildings every day that are just objects to me; but if one smells like it has barbeque inside, it’s an interesting place to me, indeed.

It’s through making sense of “space” that placemaking happens, which then informs sensemaking, and so on, in yet another loop of human understanding. The issue of space versus place plays a role in the work of Otto Friedrich Bollnow, who tackled the issue in 1963 in Mensch und Raum(Man and Space) (Verlag W. Kohlhammer). Bollnow introduces the idea of “anthropological space”—that space is not an objectively existing entity, but a human construct. This insight is behind Bollnow’s concept of hodological space, from the Greek roots “hodos,” meaning “path,” and “logos,” meaning “word” or “discourse.” Hodological space is “a space of paths, and experience, and it corresponds exactly to what we perceive if we move between two different locations.”[304]

Bollnow’s hodological space is nicely compatible with the ideas we’ve explored so far. Ecologically, paths afford locomotion between places; and “paths” are one of Kevin Lynch’s “elements” that make up a city. The context of a path is determined by what it connects, and the places it connects are bound up in the semantic, cultural needs and shared stories of the people traveling them. The space we live in is really made of places. In fact, Bollnow argues that our contemporary idea of universal space is a relatively recent invention “connected to the age of discovery and cartography of the 15th and 16th centuries.”[305] Space is a collective, tacit agreement based on generations of culturally accumulated discourse. I think this is part of what philosopher Andy Clark is getting at when he says labels are a sort of “augmented reality trick” we use for modifying our environment.[306] When we use the structures of language to explain the world to ourselves, we add to that world new structures that change what it is and what it means to its inhabitants.

There has always been a contextual relationship between place and object. A building is an object, albeit a large one; however, because of how it is used, and because people can fit inside its boundaries, it is usually experienced as a place. Likewise, a book is an object, but we read a book as a series of pages, which are also objects nested in the book, and then we refer to a particular paragraph as being in a place within the book. In a digital example, a smartphone camera app is represented as an object on a phone’s Home screen, but after the app is “opened” and we are “in” it, the app has nested structures of layouts, providing places that align with categories of action: taking a photo, editing a photo, browsing a collection of photos, and so on.

This all sounds wishy-washy, until we remember that we’re working from an embodied point of view, which always focuses on the perspective of a particular perceiver. Just as a tool can go from “present-at-hand” to “ready-to-hand” without the tool itself changing what it physically is, places can shift in what they are to a perceiver, depending on what action is happening in the moment. Context is a mutual, coupled dance between environment and active perception.

Railroads, Chickens, and Captain Vancouver

The semantic information we add to our environment plays a powerful role in how we comprehend, experience, and inhabit places. We might be able to draw a technical distinction between the physical information and semantic information around us, but in everyday, practical life, humans perceive these dimensions as one blended environment. To help illustrate this idea, here are a few stories about language and place.

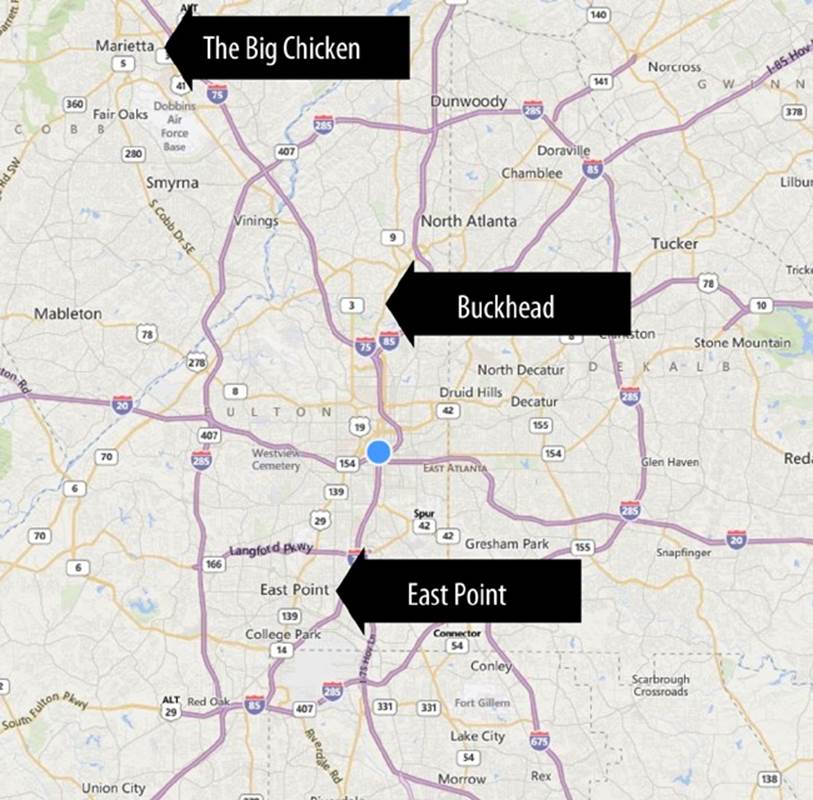

Atlanta

Recently, I returned to live in my city of birth, Atlanta, Georgia. Although Atlanta has a defined city-limit boundary encompassing around a half million people, what people culturally mean by Atlanta is the huge metropolitan area that Atlanta has absorbed: towns, cities, and suburbs that were once outside Atlanta’s borders are now part of “the Atlanta Metro Area” (see Figure 16-1). The region is home to more than five million souls, making it the ninth largest metropolitan area in the United States.

When we moved back, my wife and I bought a house in the city of East Point. Although East Point is a city of its own, it’s actually part of the Atlanta Metro Area, only about seven miles from downtown. East Point sounds like it would be in the eastern part of the city, but it’s actually situated southwest of downtown Atlanta. Why is it called East Point, then? Because it was founded in the 1800s as the eastern terminus of a railroad that terminated in the west at...you guessed it, a town called West Point. The railroad came first, and the names of the towns came later. Context is nested. It shifts and evolves, even as our labels remain.

Figure 16-1. Atlanta, Georgia[307]

Atlanta also has a district known as Buckhead. The area was first settled in the 1830s, when Henry Irby started a general store and tavern in this sparsely populated area of Georgia wilderness.[308] The community that grew up around the store and tavern gradually became known as Irbyville. According to a descendent, it was Irby himself who mounted a large deer head and antlers in the area (possibly as a parody of aristocratic folk who mounted such trophies on their walls); over time, the name of the area changed from Irbyville to Buckhead. There are no detailed accounts of how the name emerged as the official label. But if it happens like a lot of similar language events, it probably started as people telling each other directions, like, “Starting at the buck’s head, keep going north.” The object Irby mounted inadvertently became part of the semiotic shape of the environment; it stood out enough that, through the organic activity of community wayfinding, it eventually became the most easily satisficed way of labeling the area.

Just up the road from Buckhead, in a subcity of Atlanta called Marietta, is the “Big Chicken”—a giant wooden chicken-shaped sign for a local restaurant (Figure 16-2). It’s been a fixture at one of Marietta’s major intersections since the 1950s. Marietta was never in danger of being renamed Big Chicken, Georgia, because it had been officially Marietta since long before the chicken appeared. Yet, the landmark is still central to the colloquial understanding of Marietta as a place; if you ever get directions from a local, there’s a very good chance they’ll begin with, “Well, do you know where the Big Chicken is?”

Figure 16-2. The Big Chicken in Marietta, GA[309]

In all of these cases, semantic information is central to the identity and use of a place, and semantic artifacts have become part of the de facto ecological landscape. Interestingly, all of them are also situations in which commerce—that prolific perception-action-loop of culture—initiated those landmarks and labels.

In the case of the Big Chicken, the artifact is still there, just as prominent a landmark as something more permanent might be, such as a uniquely shaped rock formation (like the one in, no kidding, Stone Mountain, GA).

Vancouver

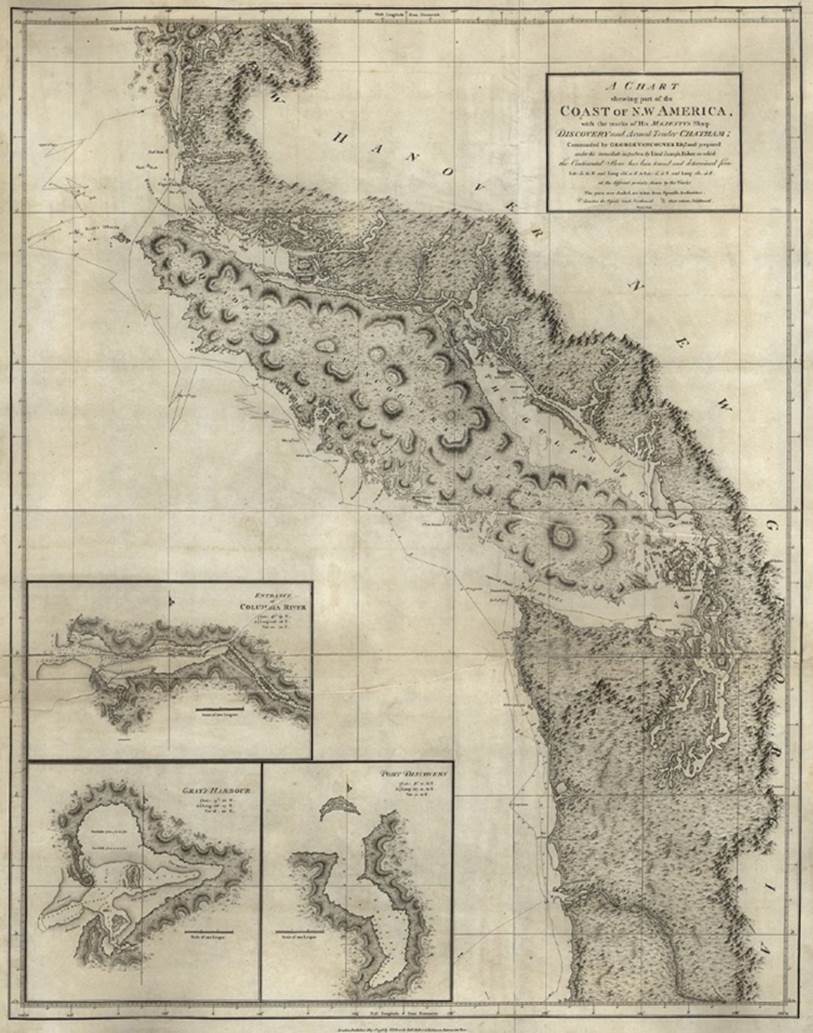

Shared semantic narratives in a given culture are part of that culture’s infrastructure of place. In the late eighteenth century, when Europeans under the command of Captain George Vancouver were mapping the coasts of the northwest Americas (Figure 16-3), they were providing their own names to what they saw, as they sketched out the contours of the landscape. Vancouver writes in his journal that the native people seemed to have a bizarre manner of navigating the sea.

London: J. Edwards, Pall Mall & G. Robinson, Paternoster Row, May 1st, 1798 ()." width="650" height="826" />

London: J. Edwards, Pall Mall & G. Robinson, Paternoster Row, May 1st, 1798 ()." width="650" height="826" />

Figure 16-3. Map from the explorations of George Vancouver: “A chart shewing (sic) part of the coast of N.W. America: with the tracks of His Majesty’s sloop Discovery and armed tender Chatham”[310]

For one thing, the natives didn’t seem to understand the logic of going in a straight line, which seemed to the Europeans the most sensible way of moving over an undifferentiated expanse of water. However, the natives’ winding routes were sensible from their perspective: they were navigating around places they believed to have powerful spirits or monstrous dangers, based on prior experience and shared lore. The natives didn’t have a written map of these obstacles, but they were inhabiting a shared map, nonetheless.

For Vancouver and his crew, it was doubly bizarre that the natives were more concerned with the particularities of the sea and the shore, and were treating the areas inland as if they were mere nothingness. But for a native civilization that subsisted mainly on what the sea could give them—and much less interested in “taming the land” for agriculture or permanent fortifications—this reversal made sense.[311]

In essence, the Europeans and the natives inhabited separate umwelts (“perceived” environments; see Chapter 4), even as they inhabited the same ecological location. They were separated not only by language, but by their respective cultural assumptions about what is valuable and what is not. For one culture, the sea was full of meaningful places, and the land was mostly meaningless, mysterious space. For the other culture, the opposite was true: the land was full of potential for strategic settlements and agricultural production; the space was the sea—what they traveled through in order to get to the places that mattered to them. Vancouver and crew weren’t an aberration. We all inhabit our own umwelts, in a sense. A family home is a different sort of place to the parent than to the child, and a city street is different for a police officer and a pedestrian, and these maps are reinforced by the cultures of parenting, childhood, policing, or civilian life.

Recall how we looked at the concept of cognitive maps in Chapter 7—it’s a tricky metaphor because they aren’t actually all that stable, and they rely a great deal on context. Not unlike those maps, the maps we share in culture are also dynamically in a state of “becoming” through our behaviors and beliefs. As anthropologist Charles O. Frake explains:

Culture is not simply a cognitive map that people acquire, in whole or in part, more or less accurately, and then learn to read. People are not just map-readers; they are map-makers. People are cast out into imperfectly charted, continually revised sketch maps. Culture does not provide a cognitive map, but rather a set of principles for map making and navigation. Different cultures are like different schools of navigation to cope with different terrains and seas.[312]

That is, we are all participants in the continual existence of these shared, cultural maps. Just as context is bound up in our action and perception, rather than a static, external property, these cultural structures we live in are reinforced, restitched, preserved, or disrupted by our participation in those cultures.

Captain Vancouver’s European explorers might have been making literal, explicitly crafted maps of the terrain they were exploring, but they already had tacit “maps” that they inhabited before they ever left on their voyage. Not just the maps they carried in their hands, but a sort of map that emerges from collective cultural activity.

These tacitly inhabited maps are culturally bound information structures that we erect and reinforce through the narratives we share and the ways in which we communicate and behave. In some ways, these culturally determined semantic realities are even more important than the conventional maps we make, because the first sort sets the terms under which the second sort are created and understood. Culture creates invariant structures that determine how we understand our experience, and the interface for that cultural map is language—the very sort of information that makes the map in the first place.

Maps are not neutral information artifacts. Because they cannot contain every detail of the world, they can accommodate only certain, chosen aspects of our environment, our culture, and our own lives. As Rothstein’s article on cartography explains, “maps are not just a progressive record of attempts to know the world; they are a record of attempts to construct and control it. Maps are not innocent. They select the data they wish to emphasize and ignore what is inconvenient. They are...instruments of power.”[313]

Author and cartographer Denis Wood argues in The Power of Maps (The Guilford Press):

The selection of a map projection is always to choose among competing interests; that is to embody those interests in the map...even if we confine ourselves to such superficially technical issues as the representation of angles and areas, distances and directions.[314]

Everything we make is full of decisions driven by someone’s interests somewhere, whether we’re conscious of it nor not. And maps are especially charged with political, social, and personal significance.

We have a great responsibility when creating information environments: even though contextual meaning ultimately depends on the perceiver, the environment has a lot of control over the perceiver’s experience of that reality. Information architectures create maps we live in, and those maps reify choices, values, and agendas. They have always been a way for one party to define the world in categories that suit that party’s own interests. What makes a place for humans has as much to do with these factors as what the physical affordances of a place provide.

Organizational Maps

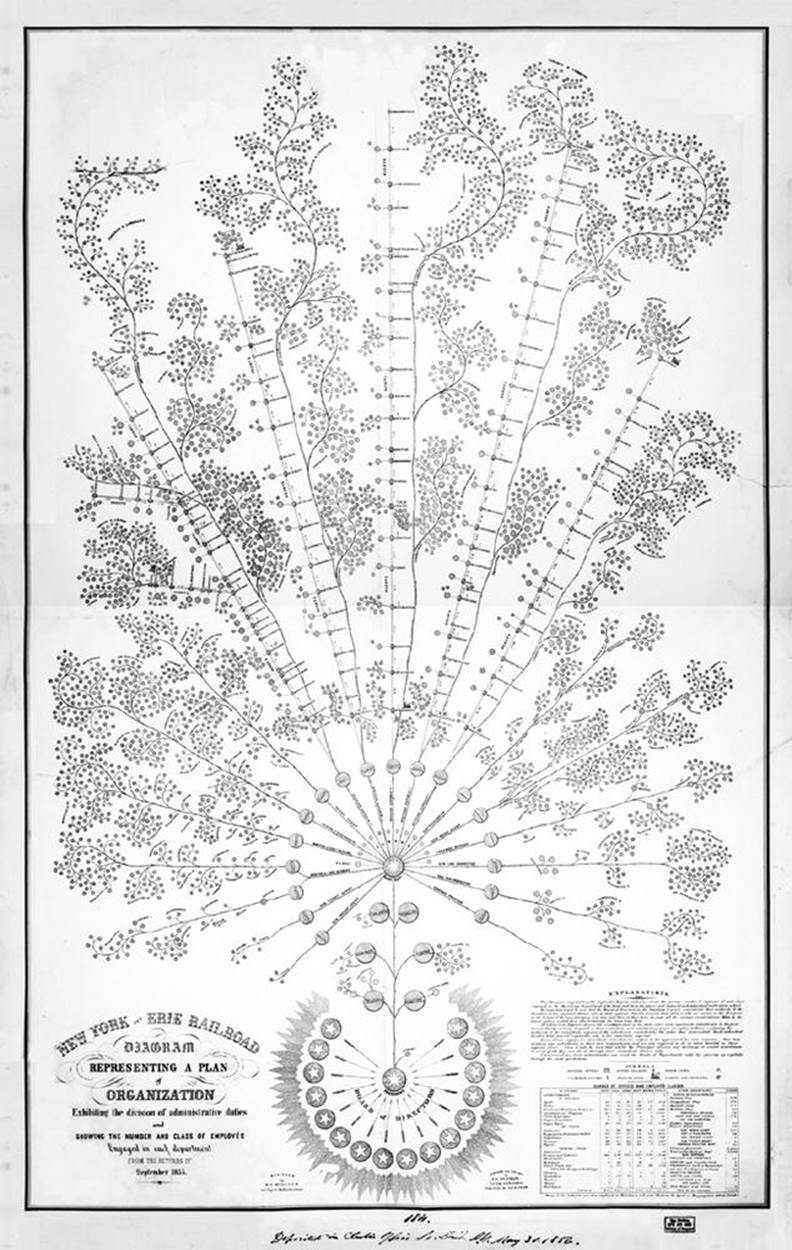

Structure is always political because it always potentially implies something about how people are organized in relation to one another. Places are made of many things, not just the ecological surfaces of the physical environment. As anyone who has worked in a modern corporation can attest, there are many structures at work in business beyond the walls, ceilings, and floors of an office building.

In Figure 16-4, we see what some say is the first corporate organizational chart ever made—the diagram describing the structure of the New York and Erie Railroad in the mid-nineteenth century.[315] Railroads were a new species of human organization that required real-time coordination across vast distances and time zones. To function, railroads required semantic artifacts such as these as much as they required tracks and switches or headquarters buildings in major cities. To a large degree, the railroad lived in the system described by this chart.

Although it’s common for the physical layout of an office structure to reflect the hierarchy of its inhabitants—big, corner offices for senior executives, smaller internal offices for middle management, open seas of cubicles for the rank-and-file—physical layout alone isn’t enough for the complexities of large-scale business.

As David Weinberger explains in Everything is Miscellaneous: “Each company has one official org chart because the flow of authority needs to be simple and unambiguous for legal reasons, not just to create an efficient decision structure.”[316] The environment—in this case the byzantine semantic architecture of legal regulatory rules—exerts controlling pressures on the shape of the corporate body, requiring it to make its own semantic structures to “couple” with those legal pressures.

Weinberger goes on to explain how this facet of information for the company describes only one official, enforced slice of the actual structures at work there. The rest tend to be more tacitly emergent: the networks of shared expertise, friendships, trusted partnerships, and other sorts of social connections.

Business uses semantic structures in other ways besides organizational command. For example, a company can recategorize workers from “employees” to “independent contractors” to avoid taxes and benefits costs—often with just a few clicks in a database.[317] Moving people semantically from one state of being to another can have a devastatingly real effect on those lives.

New York and Erie Railroad, circa 1855" width="634" height="1000" />

New York and Erie Railroad, circa 1855" width="634" height="1000" />

Figure 16-4. Organizational diagram of the New York and Erie Railroad, circa 1855

The organizational chart is just one example of how language creates structures that we inhabit. As humans, there’s no escaping the places we make with information, whether we mean to make them or not. In information architecture practice, it’s crucial to understand not only the official organizational structure, but the unofficial, tacit, cultural power structures, as well, both for the client or employer and the social structures that the organization serves—families, towns, and even other companies.

[302] Rothstein, Edward. “Map Makers Explore The Contours Of Power; New Study Tries to Break the Eurocentric Mold.” New York Times; May 29, 1999 (http://nyti.ms/1sL4yZ7).

[303] Resmini, Andrea, and Luca Rosati. Pervasive Information Architecture: Designing Cross-Channel User Experiences. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2011:55.

[304] ———. Pervasive Information Architecture: Designing Cross-Channel User Experiences. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2011:68

[305] ———. Pervasive Information Architecture: Designing Cross-Channel User Experiences. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann, 2011:69

[306] Referenced earlier, in Chapter 9.

[307] via Bing.com, annotations by author.

[308] http://www.buckhead.net/history/buckhead/index.html

[309] Wikimedia Commons: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thebigchicken.jpg

[310] London: J. Edwards, Pall Mall & G. Robinson, Paternoster Row, May 1st, 1798 (http://www.loc.gov/item/2003627084).

[311] Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004:9.

[312] Frake, Charles O. “Plying Frames Can Be Dangerous: Some Reflections on Methodology in Cognitive Anthropology” Quarterly Newsletter of the Institute for Comparative Human Development, 1977;(3):6-7.

[313] Rothstein, Edward. “Map Makers Explore The Contours Of Power; New Study Tries to Break the Eurocentric Mold.” New York Times; May 29, 1999.

[314] Wood, Denis. The Power of Maps, 1st edition. New York: The Guilford Press, 1992:57. (emphasis in original)

[315] The First Org Chart Ever Made Is a Masterpiece of Data Design Liz Stinson March 18 2014 Wired.com (http://wrd.cm/1t9Cnoe).

[316] Weinberger, David. Everything is Miscellaneous: The Power of the New Digital Disorder. New York: Times Books, 2007:182.

[317] Wood, Marjorie Elizabeth. “Victims of Misclassification,” New York Times, December 15, 2013.