PRACTICAL EMPATHY: FOR COLLABORATION AND CREATIVITY IN YOUR WORK (2015)

CHAPTER 7

![]()

Apply Empathy with People at Work

Collaborate with People

Lead a Team

Understand Your Higher-Ups

Know Yourself

Practice These Skills

Summary

Every so often, you’ll start work in the morning full of ambition for the day, only to find that a coworker is having a fit about the way something was done. Or maybe someone in leadership has requested that you drop everything to pursue something else. So much for the immense progress you intended to make before evening. Instead, your time goes toward understanding the changes, the political currents, and the gossip about who feels what about the whole thing. It’s inevitable—so much of your day goes toward interacting with other people.1 And that’s never going to change, because organizations are made up of people. It’s better to embrace the humanity of the people you work with than to expect the efficiency and productivity you might have if people weren’t people.

The halts in progress at work happen because, among other reasons, people at all levels of the hierarchy have not invested time in understanding one another. For example, if a coworker is having a fit, the reason is often rooted in others not understanding or appreciating his ideas, or because another person encroached on his area of decision-making. Nevertheless, monthly productivity reports focus on the things you get done, not on how well you relate to others. Yearly performance reviews include perhaps a small piece that evaluates your ability to collaborate. But earning the trust of people at work, understanding what drives people, deciding what to say and what to request—all these require empathy. Learning how your coworkers reason and then acting on this knowledge is paramount to your productivity. It won’t bring it up to superhuman levels, but it will reduce the frequency and duration of the halts.

You can’t apply empathy unless you’ve taken time to develop it. When you have developed empathy with the people around you at work, your improved understanding will change the way you see things and the way you speak to people. It raises your awareness and subconsciously shifts your own thinking.

Collaborate with People

You rarely get to choose whom you will collaborate with at work. Whether you’ve worked together before or not, the empathetic mindset allows you to adopt a deliberate and intentional manner in approaching your collaborators. In order to rely on your fellow employees as you work, you need to build up trust. You want to be aware of any emotional reactions so that you can see and address the root causes of difficulties, rather than lob accusations and complaints back and forth, or worse—avoid communication.

When lack of empathy is widespread, working within a broken culture feels awful. You try to do the right thing, but instead you witness everything spiral out of control. You might not even have any control in the first place. Maybe no one has power, or the people in power don’t seem to want to spend any time listening to anyone. When this is the case, a lot of people simply give up on projects, jobs, and even careers because of failed collaboration. It doesn’t have to be you.

Perennial Listening

If you spend a portion of your time listening to your peers, absorbing their motivations and intentions, you can develop the empathy you need. Since you’ll be seeing the same people again and again in your work, listening will be an ongoing project. It will also be informal—seize an opportunity to listen when it presents itself (see Figure 7.1), but don’t always put yourself in “listening mode” when you are with each person. And, as a reminder, “each person” means that these opportunities need to be isolated from other coworkers. If the opportunity arises face-to-face, but you are with others, wait for another time when you and the other person can talk privately. Be on the lookout for opportunities by phone as well. Email can work, too, as long as you are extra careful about what you write, lest it be misconstrued.

Understanding the perspectives of the people you interact with will help you adjust what you say and how you collaborate. The goal is not to persuade others to adopt your intentions. The goal is to let empathy affect your own approach. Additionally, be conscious of what you say to people. Remember the first rule of critique: If you want to say something negative, make yourself say something positive first. The neutral mindset will help you acknowledge each person’s intentions and work to improve the relationship—not necessarily toward the direction of liking each other, but toward the direction of being able to capitalize upon each other’s input to the work.

FIGURE 7.1

Seize every opportunity with individual coworkers to listen to what’s on their minds.

TIP TAKE TURNS

Maybe two of you are simultaneously interested in developing empathy. It doesn’t work well when both of you try listening at the same time. If you’re trying to understand the other person when the other person is trying to understand you, conversation is likely to stay shallow, falter, or even fall into argument. Decide who is listening for the interval; then give yourselves a break before you switch roles. The break will give you both time to digest what was said.

This same approach works with your project stakeholders and clients. Find out their concerns. Dig into the reasons behind their requests or reactions. Balance showing them that you know what you’re doing with intervals of listening. The more you demonstrate how deeply you want to understand them, the more they’ll trust and respect you. They are as much your collaborators as your peers.

Act Like a Pollinator

Bees and butterflies pollinate flowers so plants can produce fruit—however, the bees and butterflies don’t think of themselves as pollinators. They’re more interested in visiting every flower they can. They just happen to pick up a little pollen at one plant and deposit it at another. A part of collaborating with people is similar—spreading what you and others have discovered around, so everyone can rise together. The knowledge you have to offer is the empathy you develop with people that the organization supports. This empathy will be more useful if you spread it around.

Visiting people, in-person or remotely, is what’s key. There are some organizations that follow a tradition of report-writing as a method of spreading knowledge, but it’s unlikely your coworkers will read a report. Some organizations recast the content of reports in other hopefully more compelling formats, such as video, but the same problem still applies. Unless your coworkers guess in advance the value of the content, they won’t make the time to look at it. You can’t send a report around to everyone’s desk and expect it to make them excited about something.2 That is a manifestly human activity.

There are all sorts of ways to spread knowledge around. You can orchestrate a social event every now and then, to expose employees at your organization to the people whom they are serving. You can make a short presentation at a company meeting. You and your team can individually have coffee, lunch, or a short call with different key people across divisions. Each of these examples is intended to help others develop empathy through the use of already-gathered stories.3

Whatever approach to spreading knowledge you decide to use, keep in mind that a lot of people at your organization will be focused on how well the product or service works, not on how well people can achieve their purpose. Share knowledge clearly so that peers know the focus is on people, not product. It wouldn’t be surprising to hear someone echo what you hear at a project debriefing, “We’ve done all this research, and I didn’t learn anything new about our product. But, after 25 years in the business, now I can look at my customers and see them from a different viewpoint.”4

If you’re an introvert, getting in front of people may sound challenging. So don’t. Get beside them at a desk or go to lunch with them. You know where you personally feel comfortable, so come up with a way to have chats with folks. If you are passionate about what you’ve learned from people, let that passion burn past your natural reticence. Be the evangelist for the concepts you heard in the listening sessions. You don’t have to stand up in front of a room full of people.

Think of yourself as a resource for everyone at the organization. You’re the walking, talking embodiment of all the people (internal or external) the team is trying to support. When you open your mouth, their voices come out. You’ve heard plenty of stories where something surprising catalyzes an integral change. (The nurse who looks at a situation from the patient’s view and suggests something the doctor wouldn’t have thought to try.) Spread the stories to as many cracks and crevices in your organization as you can find. It’s a good side project, and it will bring you into contact with more and more people who will remember you for reaching out.

Lead a Team

If you are a manager of a team, you are responsible for nurturing creativity. Creativity and new approaches can have more impact on the success of your organization than productivity alone. Digital products, in-person services, policy-making, process design, and writing all hinge upon originality, functionality, sustainability, and the human touch, not simply time-to-complete. Productivity by itself is the core concern of managers who produce things using human labor, but managers who rely on human minds have this additional responsibility of nurturing. Creativity relies on amassing knowledge, sharing inputs, letting inspiration strike, and working through ideas together. To help your team work well together, you are responsible for teaching relationship- and trust-building through your own practice and individual coaching.

More Perennial Listening

Developing empathy in a leadership position means developing an understanding of how each person on your team reasons and what drives his decisions. It means knowing what will upset his concentration and what will energize his mind. Applying empathy as a leader means choosing your words so they do the least harm and making requests with the other person’s perspective and purpose in mind. It also means pointing the person in a direction that will increase his skills or awareness.

To this end, pursue a regular schedule of formal listening sessions with each person on your team. Informal, unscheduled sessions are also okay, but having this practice in place lets your team know that developing empathy to engender collaboration skills is an important part of your agenda with them. As usual, during the sessions you want to remain neutral with ideas, letting the team member lead the discussion. You can give broad guidelines to get things started, but remind yourself to stick to understanding this person’s reasoning, not explaining your own intentions. Try not to let your own urges overcome this neutrality.

Measuring Your Effectiveness Over Time

Summaries of the concepts in the sessions aren’t required because you aren’t comparing between team members. However, summaries can serve as a metric after each successive round of listening, to see how each team member has changed so that you can measure the effectiveness of your cultivation. Based on the progress shown in the notes, you can intentionally shift how you support each person until it fits better.

Example: New Project Leader

At a small biotech research company, one of the directors of the company, Jiyun, promoted a member of the staff, Rick, to become the group leader for a project. This was Rick’s first experience as a group leader. Within two weeks, Jiyun was hearing from members of Rick’s group that she needed to intervene. Rick was apparently treating other members of the team like lackeys, getting annoyed because people weren’t doing what he wanted, refusing to do work that didn’t suit him, hiding, not communicating, and handing off tasks instead of working with the team. In other words, he wasn’t leading. The team was upset.

Jiyun’s first impulse was to take over leadership of the group herself, because it would be easier. She could say to Rick, “Here’s how you lead. Watch me.” However, she realized this solution wouldn’t truly help Rick become a leader, and worse, it might cause him embarrassment. Plus, she hadn’t heard his side of the story. So she asked to meet with him about his leadership of the group, making sure he had ample time to put his thoughts and complaints in order before they were face-to-face.

During the meeting, she began by thanking him for some of his prior good work. Then she asked how the project was going. She stayed neutral and listened closely. It turns out, Rick was feeling really overloaded. He said people didn’t listen to him and went off and did the wrong thing, making him spend twice as long with them explaining what he needed. He said his team wasn’t being efficient, and that they would bring him problems that added to his workload. He was ending up doing everything himself.

Jiyun realized that the magnitude of his agitation was a lot higher than she expected. Perhaps she’d assigned too much work, with deadlines too close, for a new group leader. In her response, she began by acknowledging that he was under too much pressure. She apologized for not starting him out with an interval of a smaller workload, so he could find his balance. Even though the projects and deadlines were important to the company, she emphasized to him that his role as a leader and facilitator were more valuable in the long term. She also told Rick that she did not want to step in and have any involvement in the project. It was his responsibility. And she’d like to meet with him every other day to talk about how the leadership role was going.

At the next meeting, Rick came up with some great process ideas and asked questions about the needs and roles of the other team members. He asked how he should respond when people asked him questions that he couldn’t answer. Jiyun was really pleased to see that he was starting to think about his role as a leader instead of acting like he had to do all the work himself. They discussed answers to his questions, and the meeting ended on a really positive note.

The next day, as Jiyun was walking through the building, she noticed Rick and his team discussing a project in the break room. She could see by their faces and body language that things were going better. Later that day, she asked a few of the team members how things were going. “Night and day,” they said. “I don’t know what you said to him, but it’s made 100% difference.” Jiyun was pleased that she’d kept neutral in the situation and had learned where Rick was coming from. She was pleased she’d given Rick the freedom to think of his own ideas about how to lead the people in that group, rather than just telling him what to do. Instead, he tapped in to his own good skills and behavior—exactly the things that caused Jiyun to promote him to group leader in the first place.

Culture

Team culture is a tricky thing. On the one hand, if everyone likes working together, creativity and productivity both go up. On the other hand, having too homogeneous a culture leads to group think: forgetting to be aware of other perspectives than what the group has in common. It also leads to rejection of people who do not share preferences and opinions, and to outright discrimination.5

To avoid falling into this trap, go deeper than preferences and opinions. Look at guiding principles, and you’ll find there is a lot more in common at the root level than at the level of preferences and opinions. Encourage people to search for deeper connections

Alternatively, team members may have different guiding principles. A guiding principle like “If you have to ask for help, don’t put too much pressure on the person you’re asking” could be the root of rocky relations between two coworkers. The coworker being asked feels pressure. His guiding principle subconsciously causes him to push back on his coworker. He wonders, “Is it really a crisis? You say almost everything is a crisis.” Exposing this difference in principles can help the other coworker ask for help in a different manner.

By figuring out what makes your team members tick, you can build a team culture where they get the cognitive and emotional support they need to be creative. Culture can’t be forced.6

Understand Your Higher-Ups

Executives at your organization may be clear about the direction of your combined efforts, but have they communicated the depth and philosophy of it clearly? In most cases, they have communicated clearly—to their direct reports. But once the message moves down the hierarchy, the clarity and depth of focus become lost. Like the game you played as a child, passing a whispered message around a circle of friends, the accuracy of the message depends upon communication skills and each person’s awareness of his assumptions. In some cases, the executives don’t communicate the reasoning behind their decisions, but savvy direct reports ferret it out on behalf of everyone else at the organization. In other instances, no one at the organization can really articulate why decisions were made.

Search for the Reasoning

No matter where you are in the hierarchy, it is important to know the underlying purpose of a directive so that your creativity, innovation, and collaboration will benefit. If you don’t personally understand the reasoning behind any organizational decision, you owe it to your professional standing to find out. If you are the person who is making the guiding decisions, writing down the reasoning and guiding principles behind it will help you clearly communicate these deeper intentions.

If you’re not the decision-maker, then you’ll need to reach out to the hierarchy above you to find out. The decision-makers in your organization may be inaccessible.7 There actually might be rules about who can impinge on an executive’s time, in order to protect that leader from unnecessary details that his direct reports should be handling. So find the right person who may know the deeper reasoning and ask.

You can start with a query like, “So I can better support the <insert direction here>, can you tell me more about the thinking behind it?” If that probe doesn’t yield rich answers, you can add questions about the decision-maker’s concerns and risks he is facing. If no one you ask has these answers, then you’ll want to campaign for someone higher up to collect it—someone closer to the executives. The knowledge is important for everyone to be able to support the organization in the best way possible.

Decision-makers at the top are concerned with the longevity of the organization, as they should be. Deeply understanding the people your organization supports is secondary for them; in reverse, understanding the people you support is primary for you, and the success of the organization is secondary. There are details that are necessary to pursue for each objective. Getting to the purpose underneath the details of what your organization is doing might be an ongoing process, depending on how much your organization changes each year. It may benefit you to conduct ongoing listening sessions with your decision-makers.

What you find out, in the end, is that you are understanding where your leaders are coming from, and it changes the way you approach your work (see Figure 7.2).

FIGURE 7.2

People will work from different perspectives of a stated goal, unless the underlying purpose beneath a decision is communicated clearly.

Pushing Back Is Not Rebellion—It’s Collaboration

You probably want your organization to succeed so that the people it supports gain from it and you can continue to work there. When you receive a task from decision-makers, it makes sense to understand the request as deeply as you can so that your work produces the best possible outcome. Too often, requests get accepted at face value, along with all the assumptions that stand in for actual discussion. Ideation and work cycle around the request without much broad insight. Like the story of the Chinese emperor’s court, it would empower more people if you build the canal system not the tower to heaven. It is more powerful to exhibit understanding than competence. The empathetic mindset is not focused on oneself or one’s own abilities.

Prod each request you receive to understand where it came from. Maybe your decision-maker has asked you to write a newsletter about specific topics. Why the newsletter? What is his purpose? Questioning someone to get more information about what is driving the request is not a form of disrespect, it is collaboration. You can discuss the intent behind the newsletter and explore what supports the people it is intended for. Do this with deference and respect for the decision-maker, who has reasons for his request, and together you may come to a different conclusion. You will envision richer approaches to the topic he wants to communicate.

Embrace your role as a member of the team responsible for the success of the people your organization supports, as well as for the continued success of your organization.

Know Yourself

The hardest part of working with people is remembering that your own reactions and attempts to communicate can have unintended consequences. It’s futile to try to stop yourself from having reactions entirely, but you can certainly aim to understand the circumstances and triggers that cause your reactions. Being able to simply name them will help you dampen their effects and put your purpose back at the center of your focus. It can then help you clarify the way you communicate with others.

NOTE 故曰:知彼知己,百戰不殆;不知彼而知己 , 一勝一負 ;不知彼,不知己,毎戰必殆。

So it is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself, you can win a hundred battles without a single loss.

If you only know yourself, but not your opponent, you may win or may lose.

If you know neither yourself nor your enemy, you will always endanger yourself.8

—Sun Tzu, military general, strategist, philosopher

As Sun Tzu said, half the equation for avoiding danger is knowing yourself. How can you untangle or decode your own motivations? One approach is to try looking for the same three kinds of things in your own reasoning that you look for in listening sessions: thinking, reactions, and guiding principles. See if something you’re communicating is a preference or an opinion; recognize if it’s conjecture. Try to spot when you are speaking in generalities or focusing on explanation. Using these metrics, you can become a little more aware of what you express to others. You can add to these a description of your deeper reasoning, making the meaning of your communication more forthright.

Another skill to develop is being aware when another person is having an emotional reaction during an interaction with you. This talent is a little harder because first of all, it occurs during discussion with someone you work with, so you might be anxious or embarrassed about trying. Second, recognition always occurs at least a few beats after the other person expresses his emotion. When you do recognize it, you have the chance to slow down and ask the other person about his emotion. If he needs it, give him permission to withdraw from the situation until later. Recognizing another person’s emotion helps you manage your interaction with that person.9 You will be better prepared to keep yourself on track.

Finally, at an interpersonal level, examine your intentions. Are you participating as a team member, or as someone who is trying to be at the head of his class? An apt analogy is playing an instrument in an orchestra. Much of what you play is in support of another instrument, and different instruments switch roles and play the lead. Nonetheless, all the musicians focus on the power and emotion of what you are creating for the audience. If you’re more sports-inclined, the team metaphor works as well. You pass the ball to the person best situated to help the team score. Understanding your teammates and encouraging them when it’s their turn to do their thing—this is empathy playing out in your interactions. This kind of empathy can help not only between team members, but also across divisions within your organization.

Practice These Skills

Becoming more intentional in how you interact with people at work is not something that’s going to happen overnight, no matter how much you wish it would. Try out some of the ideas in these practices.

Practice 1: Know Yourself

Listening to yourself is an additional way of practicing your empathetic mindset so that later you can draw forth similar clarity from people you listen to. Moreover, when you acknowledge the role that emotions play in your own reasoning, you can identify emotions more easily in others.

Here’s a chance to practice self-awareness. Think of a recent event you were involved in where things didn’t go as you expected. Things could have gone worse, or better, or simply in a different direction. It doesn’t have to be an important event. Anything will work: you heard some surprising family news, you were involved in a difference of opinion, you accidentally broke something, or you had a problem at a restaurant, for example.

On a blank page, make three sections and put these three headings at the top of each section: Thinking, Reactions, and Guiding Principles. Then try to remember as many details about the event that you can and write down your internal “thinking process” as the episode unfolded. You don’t have to keep everything you write in chronological order.

If you feel like it, add columns for any of these other types: opinion, preference, explanation, generality, passive behavior, and conjecture. See what parts of your thinking and speaking fall into those columns. It’s not “bad” to have entries in those columns—it just means you need to work on giving greater depth and clarity to the entries in the next event you experience. You want to focus on putting more concepts in the Thinking, Reactions, or Guiding Principles columns.

Example: Miles’ Story of “When Things Did Not Go as Expected”

At the time, Miles was a member of a research team, even though his background was in visual design. The research team was made up of people from two companies that merged, and Miles was excited to be part of a team exploring a deeper understanding of the people the company served. Miles had scheduled a listening session, and this was only his second time using the conference call system. The first time he used the conference system, it had been a confusing and frustrating experience. Luckily, other team members were on that first call and started the recording for him, so he could concentrate on the person instead of the technology. However, this particular day, no one else from the team could join him to help, even though they had agreed to. He was concerned that he would end up failing to make the conference system work, thereby inconveniencing the customer.

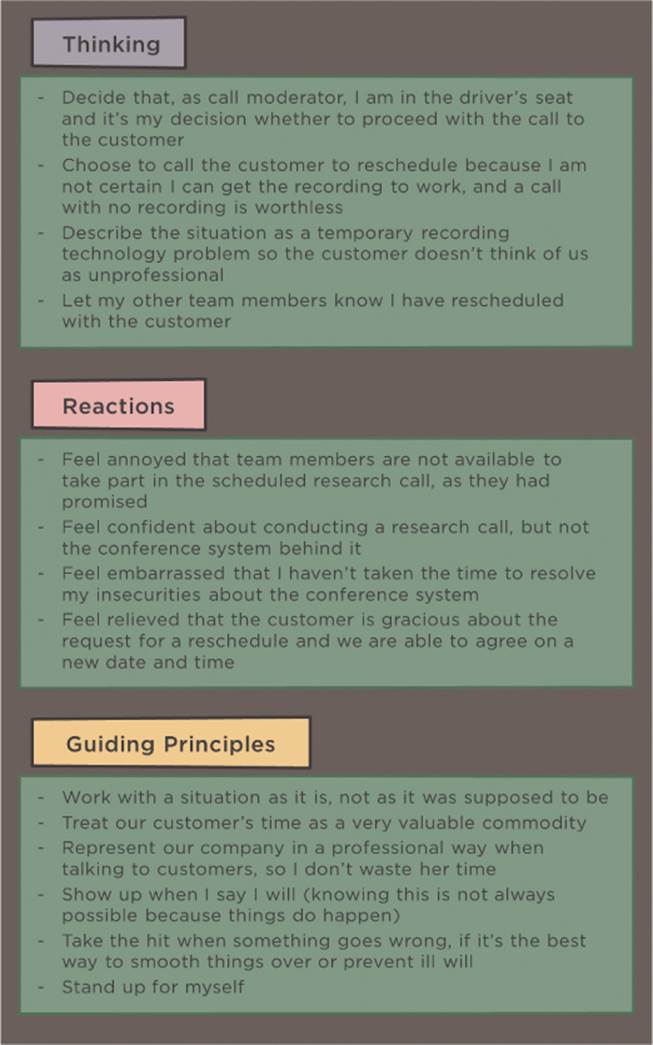

Afterward, listing his thoughts and reactions helped Miles put his emotions in perspective. It also showed him that he behaved according to his principles during the event, which reestablished his sense of worth. Here are the things that went through Miles’s mind as the morning unfolded (see Figure 7.3).

FIGURE 7.3

Here are the lists that Miles wrote after the morning at work when things did not go as planned. These lists helped him feel better about how he handled things.

Practice 2: Begin to Understand Your Decision-Makers

If you want a deeper understanding of the purpose behind what you are asked to do, you need to hear the reasoning from the person who makes the decisions. You need to be able to ask for clarification. You can gather this understanding either directly from this person (from his direct reports) or further down the chain (if he has been successful at explaining his reasoning to them). Don’t let your assumptions about those people higher up in the hierarchy stop you from getting clarification about purposes. You need this understanding so that you can support this person with your best work.

1. List people who give you work requests. They don’t necessarily have to be your immediate manager, especially if that manager is simply relaying orders. If you don’t know who they are, start asking around.

2. Find out from your peers whether each of these people has been willing to explain the detailed purpose of a request to anyone else. You want to know if any one of them has a closed-door policy, so you know what to expect and what others have experienced.

3. Find out where these people spend their time. If any one of them is in a location far from your own, you’re facing a bigger challenge to establish a collaborative relationship. You will probably need to rely on remote conversations.

4. Find out who tends to meet with these people. Your goal is to find out who might have already done your work for you—asking the person details about his purpose for each request. If someone has already done this, you can collaborate directly with this person, going back to the requestor if you both come up against alternatives that need clarification.

5. If no one else plays this role with the requestor, then you can advertise that you need more in-depth information to better support the request. You will end up either working with a person in between you and the requestor in the hierarchy, or you’ll have a chance to meet a few times with the requestor himself to gather deeper information. There is also a chance you’ll be somehow forbidden from getting clarification. If this last scenario comes true, then keep asking good, solid questions about the purpose of the request, to demonstrate the kind of knowledge you need in order to better execute the request.

6. If it seems likely you will get time with someone much higher up, find out how he prefers to approach his meetings. Prepare for the meeting, doing your best to read everything you can find about this leader and his perspective and history.10 This meeting is about understanding intentions with someone who has limited time; you want to see what you can learn about the other person’s thinking via what has been written first.

Summary

The empathic mindset can be applied to the people at work. You can gather understanding from your coworkers, from the people you manage, and from the leaders of your organization to enlarge the way you see things and change the way you speak to and support the people around you—and even shift your own reasoning.

COLLABORATE WITH PEOPLE

• Spend a portion of your time listening to your peers.

• Adjust what you say.

• Acknowledge the other’s intentions.

• Find out concerns of stakeholders and clients.

• Act like a pollinator with empathy you’ve developed.

LEAD A TEAM

• Pursue a regular schedule of formal listening sessions with each of your team members.

• Nurture creativity and help your team work well together.

• See how each person has changed so that you can measure the effectiveness of your cultivation.

• Shift how you support each person until it fits.

UNDERSTAND YOUR HIGHER-UPS

• Find out the reasoning and purpose behind each direction and request, so you can better support it.

• Search higher and higher up the hierarchy for a person who can explain these to you.

• Pushing back is not rebellion; it is collaboration—enabling a discussion to understand reasoning.

KNOW YOURSELF

• Understanding your reactions and triggers helps you focus and communicate better.

• Categorize what you say; is it reasoning, reaction, guiding principle, or is it opinion, conjecture, etc.?

• Recognize other people’s emotions so you can check your own reaction and stay on track.

• Defer to your teammates when it’s their turn.

Practical empathy helps you understand the purpose and methods of your organization.