REBUILDING CAPABILITY IN HEALTHCARE (2015)

4. Application to Real Life: Project Case Examples

The list of projects conducted in healthcare using Lean Sigma methods likely touches virtually all aspects of the business. Here, the focus is on the leaders’ learning, and so the selected case examples reflect both different problem types, but also different Lean Sigma approaches. For each example, attention is focused not so much on the solution itself, but rather on the characteristics of the business situation and the path used to get to the solution.

The cases appear in approximate order of complexity of approach.

Case 1: CT Capacity and Throughput

Background/Situation

A hospital’s radiology department includes a computed tomography (CT) department with two scanners, conducting approximately 750 scans per month. The hospital was experiencing decreasing volume and losing associated revenue to a freestanding competitor. Initial Voice of the Customer (VOC) work had indicated that much of the volume loss was due to the hospital requiring that patients schedule tests in advance (on average more than two days), whereas the competitor accepted walk-ins. Some same-day scans were feasible, but the process was convoluted and difficult for both the patient and the department.

In its baseline state, both inpatients and outpatients (ED and scheduled ambulatory patients) were distributed across both scanners, and all staff played all roles, with no real clarity of who owned what at any time. Both scanners were considered to be at, or nearing, maximum capacity.

The focus of the project was to increase the CT capacity, create greater access for patients, and recoup as much lost patient demand as possible.

Approach

Given that the CT department was relatively small and the project urgency was very high, the usual Lean Sigma or Kaizen approaches (as described in Chapter 3) were not attractive options. The organization elected to do the majority of the solution concept design in a single two-day Kaizen-type event, led by the author in the role of Master Black Belt.

The choice to use an external resource mainly related to the inexperience of the Black Belt leading the project. Given the criticality of the outcome to the organization, use of a seasoned resource was deemed a better prospect for success.

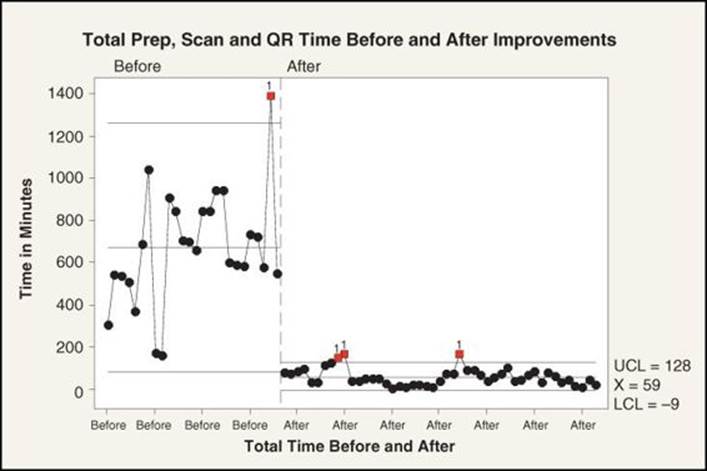

Prior to the event, three or four one-hour team meetings were conducted over a period of about a month to charter and prepare the work and to plan, capture, and analyze data related to demand, cycle times, staffing, and VOC. Many of the flow changes were made during the two-day event, but some long-lead-time items, such as changes to staffing levels and staff competence, were managed through a series of meetings after the event, over a two-week period. The overarching project timeline is shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 High-level phases of CT Capacity and Throughput project

Changes Made

The majority of the improvement came from reducing the lost room capacity due to pre- and post-exam work being conducted in the scanner room. Before the event, there was activity in the exam room that didn’t need to occur there. For example, patient histories were taken pre-exam, and patient instructions were given post-exam. Both activities are important but can be done outside the exam room. In addition, clear, simple, repeatable, and singly accountable roles ensured no lost time due to “do-overs” or missed activity.

The increase in capacity allowed all the outpatient “runners” to be put on the single fastest scanner, thus freeing up the second scanner for inpatient work and longer procedures, further reducing delays due to the scanners being tied up simultaneously.

Results

The capacity increase was significant (the Overall Equipment Effectiveness1 was increased five-fold) with a corresponding reduction in outpatient turnaround time from 23 minutes to less than 10 minutes. This enabled the department to accept walk-ins, thus recapturing substantial volume from the freestanding competitor.

1. Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) in Lean Sigma is an analogous but more sophisticated measure of utilization and relates actual capacity to potential capacity. In simple terms, a process running at 100% OEE is up 100% of the time, doing only value-added work, is going as fast as it has ever gone, and is running with perfect quality. See Wedgwood, Lean Sigma: A Practitioner’s Guide, pp. 311–17.

Within a matter of weeks volume was up 30% with a corresponding 38% increase in revenue. Spreading the fixed overhead of the department across many more scans significantly improved margins.

Leadership Learning

Such a simple project has many learning points for leaders:

1. Within a small department it’s possible to change the project structure to cater for reduced availability of team members.

2. It’s often useful to apply external resources as Project Leaders when internal resource bandwidth or capability is limited and when rapid change is required.

3. For large opportunity projects touching the external market, it is recommended to conduct a VOC data capture and analysis to ensure that the focus of the project is most relevant.

4. Once a simple accountable set of roles is developed for a process, the system as a whole becomes very resilient and is sustained well (see the Epilogue for this case study).

5. It’s possible to dramatically increase the capacity of a process, even when it has been considered to be “maxed out.”

Epilogue

This particular project was completed in 2007. Some five years later the author met one of the Kaizen participants, a CT tech, in the cafeteria at the hospital. She was still excited about how well the process was running and volunteered to talk to other CT departments attempting the same goal (including the team described in Case 10). Her main message regarding why it was so successful related to how with simple accountability in place, there was, in her words, “. . . no longer any place for low performers to hide.”

At that time the volume had increased drastically from the initial 750 scans per month, and the same process was now conducting on average around 1,300 scans per month.

Case 2: Reduce Discharged, Not Final Billed (DNFB)

Background/Situation

A hospital commenced its Lean Sigma journey and selected a variety of business targets for initial projects. One such target was the ability to quickly bill for services rendered. Net revenue of approximately $200 million and an average DNFB2 of 11 days equated to more than $4 million outstanding unbilled at any time.

2. DNFB is defined as unbilled net revenue divided by average daily net revenue.

A DNFB of less than five days is a reasonable goal for most organizations, thus representing, in this case, a project opportunity of more than $2.5 million cash.

Approach

Given that DNFB was impacted by multiple sequential processes through the organization’s Health Information and Patient Financial Services, the approach taken was first to conduct “discovery” work across a very broad scope of processes and then, based on the learning gained, focus the subsequent project work on the greatest source of opportunity, in this case the processing of paper charts in Health Information.

Once the Health Information focus was determined, the project followed the typical Lean Sigma roadmap as described in Chapter 3.

Changes Made

Scanning, or imaging, paper documents into an electronic record archive constituted a significant activity in the DNFB process. Instead of segmenting the imaging process by activity and working with batches of charts at each phase, the team organized a single-piece flow. Two methods of chart flow were instigated; either a single person or a pair of staff managed each chart through the entire process. Work patterns were established, along with workstations and layouts that met physical needs. Staffing patterns were changed to match chart volume.

Results

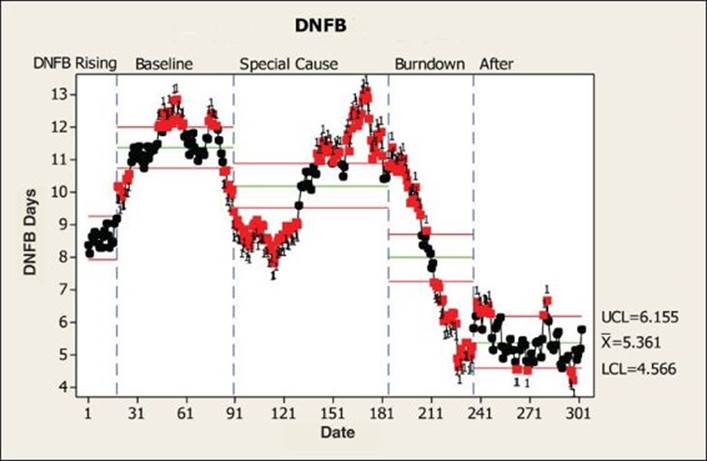

After the introduction of the changes, results were dramatic. As shown in Figure 4.2, the time required to prepare, scan, and review a chart declined from an average of around 11 hours to less than 1. Equally important to staff is that now it is rare that one shift leaves work undone for the next shift, and when they do, it is quickly completed.

Figure 4.2 Reduction in processing time in Health Information

DNFB days dropped from an average of 11 days to a sustained rate averaging 5 days. At the same time, the hospital brought a one-time increase of nearly $2.5 million in revenues to its bottom line, as verified by the chief financial officer. Also, the Team enabled staff to improve the time when charts are available for clinical and operational reviews, updates, or readmissions.

Leadership Learning

Key leadership learning points for this project include the following:

1. Focus on cash processes is good for quick return, especially in the early stages of a Lean Sigma deployment. Once the process change is made, the cash shift can be realized in as little as a few weeks (unlike profitability change projects, which can take months or even years to make a similar impact).

2. When the specific failing process is unknown, it’s prudent to scope the project broadly initially (with a “discovery” thinking) and then scope down later once the target process has been determined.

3. It is very common that, on hearing of an impending project in their area, operations leaders (Process Owners) try to solve the problem independently, often by throwing resources at it, with no real change to the process. Figure 4.3 shows this initial attempt (labeled “Special Cause”), after which the process performance reverts to its baseline.

Figure 4.3 DNFB performance over time

Case 3: Radiology Denials

Background/Situation

A medium-size regional health system, given the financial tightening during healthcare reform, was looking at all process opportunities for reducing costs. The internal Revenue Integrity Team had identified a potential issue with payer denials in radiology.

Prior-year data showed denials of approximately $660,000 with a similar run rate in the current year. The situation was complicated further by a number of physician office changes under way to ensure that revenue was secured for the health system and not diverted elsewhere.

Approach

Given the magnitude of the existing performance improvement under way, the Lean Sigma Steering Team elected to use the author as an external resource to lead an initial Kaizen event to design the new process and implement where possible. Subsequent to the event, internal performance improvement leads could follow up to ensure that all of the changes were implemented and the Control Plan was fully functional.

Changes Made

During the event, it became very obvious that the process was overly complex, with no clear ownership at any stage. More staff were being used to inspect and rework the patient accounts than were doing the work in the first place. A simple process with clear accountabilities was developed.

Second, the complex pre-authorization work was falling on multiple lesser-trained individuals in the physician offices, rather than on the higher-skilled resources (currently focused on the inspection and rework). The simple tenet of “Do it with the right skilled person, right the first time” drove the team to a model of using revenue cycle experts to do the authorizations and free up the physician office staff to focus on scheduling and registration and easing the patients’ journey to the next point of care. This was a win-win-win for all of the involved parties.

Results

Since the implementation of the changes, the denials were reduced by more than 50%. In addition, by simplifying the process for physician offices, the changes caused a few key physicians to reconsider their stance of using an external competitor for their CTs. The hospital subsequently captured some 250 additional cases per month in CT.

The bigger impact, however, was that this event helped the leadership to recognize the potential in the revenue cycle and to subsequently launch a program to simplify and strengthen processes across the breadth of the revenue cycle.

Leadership Learning

Key learning points for leaders are as follows:

1. Sometimes it’s important to spend a little extra to get a project done now, rather than wait until internal resources are available. If the organization is losing significant money every month, it’s important to consider the opportunity cost of not doing the project, which can outweigh the additional investment in external resources to lead the project.

2. External benchmarks can be useful to identify potential project opportunities but should not prevent a project from being tackled. If this particular organization had gone by benchmark alone, it wouldn’t have commenced the project at all, but the raw level of denials at $660,000 per year (much less than the $3 million benchmark best practice) couldn’t be ignored.

3. Involving and engaging the right people, both on the Team but also as Champions and Process Owners, is critical. For some reason, organizations default to a single project Champion, when in reality two or even more are required to bring about the change.

4. In more recent times, the avoidance of adding staff to gain a desired return is almost at paranoia level. Too many times, organizations are losing out on multiple times return on investment (ROI) because they don’t want to add a required full-time position. There has also been a preponderance of cutting heads in the wrong place (at the front lines) and then adding them back in the wrong place (service line directors) when performance inevitably drops. A great tenet here is to simplify, add the right resource where it is needed, empower the front line, and manage performance.

Case 4: Behavioral Health Discovery

Background/Situation

A large not-for-profit provider of community-based behavioral healthcare had seen a key performance indicator for patient satisfaction well below benchmark for some time, to the point of impacting remuneration. The patient group in question was adolescents (the patient satisfaction surveys were actually being filled out by the parents, not the patients themselves).

Many changes had been attempted, but nothing seemed to move the performance. The organization took advantage of a local hospital Black Belt training wave and added three key leaders to take the training, with this particular project being one of the three chosen for focus during training.

Approach

Given the absolute lack of data and understanding of why the patient satisfaction was so low, the chosen project path was one of discovery, specifically of the VOC. In effect, the project followed Define-Measure-Analyze and then spawned a number of actions and subsequent projects based on the new customer insight.

Changes Made

Based on the VOC work, there were a number of subsequent areas of activity, the two most notable being these:

1. They were measuring patient satisfaction differently from the organizations to which they were being compared. Simply resetting the measurement to match standard helped greatly.

2. Some earlier changes such as the removal of provision of transport as a cost-cutting measure (which was deemed unnecessary) had in fact had a very marked negative ramification.

Results

The largest positive result here was likely the big step forward in understanding customer need. Based on simple changes based on the VOC work, patient satisfaction was elevated to new levels that were higher than had ever been experienced in the past.

Leadership Learning

Key leadership learning from the project is as follows:

1. A great place to look for Lean Sigma projects in the organization is where performance is still low despite multiple attempts to remedy the situation. Often these are avoided because of a concern that there is limited value or there perhaps isn’t a high chance of success.

2. Being brave enough to admit that “we don’t know” was tough for leadership, but committing to an open-ended VOC activity brought significant return.

3. Sometimes one project isn’t a single project but in fact spawns many others. Sometimes the project we’re working on now is merely an enabler.

Case 5: Medication Delivery

Background/Situation

A medium-size regional hospital in the initial stages of a Lean Sigma deployment had selected four Black Belts to be trained and a spread of projects across the organization to learn what Lean Sigma could accomplish. A competitor hospital had recently had an adverse event due to a medication error, and most hospitals in the region had heightened sensitivity to the issue. An earlier isolated project had examined medication administration, and this project was a continuation of that work.

Approach

The project was scoped to just first-dose delivery to inpatient units, from order written to medication available to nurse for administration. Initial data captured indicated an accuracy rate at around 93.5% for getting the medication to the nursing unit with the “five rights” (right med, right dose, right route, right patient, right time) and an average delivery time of 86 minutes.

The project followed the Lean Sigma project approach as described in Chapter 3, first streamlining the process and then giving heavy scrutiny to the accuracy and reliability of the delivery itself.

Changes Made

Changes focused on two main areas: first, how meds were stored on the inpatient units, and second, the flow of the process to and through the pharmacy.

Current practice is often for hospital units to store medications in, and dispense them from, a medication vault that tracks the inventory. Historically, at this hospital, only controlled and a limited number of commonly used meds were stored on the unit in med vaults. The team elected to include all high-usage meds in the vaults to eliminate the lengthy and potentially unreliable process of delivery from the pharmacy.

The pharmacy flow was redesigned to give quiet, focused attention to order entry, rather than it being done in the hustle and bustle of the main pharmacy area.

Attention was paid to the layout of both the pharmacy itself and the med rooms on the inpatient units.

Results

As a result, the hospital reduced average medication delivery time by 60% and improved accuracy of the first dispensed dose to just one error in greater than 18,000 opportunities, a thousand-fold reduction in errors.

In addition to the accuracy and timeliness, some unexpected results included more than $200,000 annually in recovered charges along with a 55% reduction in the number and 60% reduction in the length of phone calls between the nursing units and the pharmacy.

Leadership Learning

Key leadership learning for this project includes the following:

1. Results can come from multiple areas: timeliness and accuracy of med delivery, phone calls between inpatient units and the pharmacy, nurse interruptions, charge capture, work content of the process, reduction of paperwork in the process, and elimination of reconciliation of copies of paperwork where splits in the process have occurred.

2. Often healthcare processes are so messy that in order to increase accuracy, it’s important to streamline the process substantially (the inherent quality of the process is a function of its complexity).

3. Many processes require more than one Champion to bring about success. Here it was necessary that both the director of nursing and the pharmacy director be Champions. Without either one, the project would likely not have succeeded.

Case 6: Registration Standardization

Background/Situation

A medium-size regional hospital approximately six years into its Lean Sigma deployment, having completed more than 40 projects, was beginning to see patterns in sustainability of results. Where processes were clearly understood, repetitive, and with a relatively short cycle time, such as in pharmacy and lab, process improvements were well controlled and sustained. In other areas there were some struggles.

Discussion with executive leadership resulted in articulation of the problem as a lack of understanding of (process) performance management. An organization-wide initiative commenced to roll out process standardization and performance management. Each department was required to identify at least one core process to standardize.

Main registration was selected for the pilot work and was led by the author (an external resource) with the commonly used theme of “If we’ve not done this internally before, let’s watch it being done right and we’ll learn from that.” (Case 7 was the subsequent, more complex event and followed the same thinking.)

Prior to the work, patient satisfaction with registration was at the 76th percentile.

Approach

The project followed the two parallel standardization paths, as described in Chapter 3 and depicted in Figure 3.11. The first path focused on the registration process itself. Through use of a two-day standardization event, the team laid down the standard process and created the Standard Work Instructions. During the event, a draft Control Plan Summary was developed.

The second path was aimed specifically at the frontline manager and supervisors in the area, guiding them in the project output they were being given, what it meant to have a standardized process, and how to manage performance.

Changes Made

Since this was a standardization approach, some streamlining of the process was involved, but there was no substantial (new to the organization) change. There were many of the same process steps, but some were done in a slightly different order. In addition, the team applied workplace layout design principles to the registration booths and main registration area.

Results

Subsequent to the event, patient satisfaction has risen from the baseline at the 76th percentile to consistently higher than the 95th percentile and has been sustained.

Leadership Learning

Leadership learning from this project includes the following:

1. Given that this was a first attempt at the new standardization approach, an external facilitator was used and the chosen target area was relatively small, self-contained, with an important and quickly cycling process.

2. Two distinct parallel paths were used: first, to say what we do, and second, to do what we say.

3. Staff quickly realized that performance management isn’t about “big brother watching me” but relates closely to equitable distribution of workload. With this realization, the staff in the registration area asked to move from measuring staff productivity monthly to twice a shift.

4. Unlike a change project, it was important to include the Process Owner (registration manager) on the Team to ensure that the standard process was clearly understood and staff could be held accountable for it.

5. Building the requirement that managers standardize their processes into their annual performance appraisal quickly drove the culture of standard work into the organization. As shown in Figure 3.11, three audits were used: one to get a 3 on the scorecard (gained after completing the event), the second to get a 4 on the scorecard (gained once all standard tools were in place), and finally to get a 5 on the scorecard (gained with a presentation to the audit team).

Epilogue

Very quickly after go-live the manager became free of getting drawn down into the weeds of expediting patients and was able to get back to real managerial duties. She very much embraced the approaches and quickly moved the staff members to standardize all the other registration processes.

Case 7: Inpatient Admission Standardization

Background/Situation

This case was conducted at the same organization as Case 6, as part of the standardization initiative. Once the initial registration pilot was complete, some reasonably small departmental processes were tackled, but when inpatient nursing was to be addressed (considered a higher-complexity and higher-risk undertaking), the same approach of using the author as an external facilitator for the event was used.

The admission assessment process was selected as being a core nursing process, with the notion that if it were done right, many potential failures/problems later in the process would not occur.

Approach

The same approach was used as shown in Figure 3.11 in a longer four-day standardization event. Representation from all nursing units was included in the event, as well as all nurse managers. Mentoring in performance management was given in parallel to nurse managers and supervisors.

Changes Made

The Team concluded that most issues in the process could be avoided if the RN conducting the assessment was not interrupted. Even though this was a standardization event, the Team elected to make a change to the process and have the RNs hand off their phone to their second prior to the assessment.

The assessment itself was streamlined and sequenced for maximum efficiency.

Results

The phone handoff proved to be a critical X (factor) in the process, driving out more than 40 minutes from the assessment duration, along with a reduction in variation; in other words, the work was done more consistently and more efficiently.

Leadership Learning

Leadership learning from this project includes the following:

1. When improving a lengthy process or sequence of processes, it’s often good to start at the front to get things right the first time (everything flows from there).

2. If all nursing units are impacted, it’s imperative to get all the managers in the room. If we are looking for one standardized process, there’s really just one decision-making body.

3. It’s often tough to get different units to buy in, even when data is presented. It takes constant reinforcement from leadership.

4. Building key process measures into a manager’s scorecard will drive sustainability.

Case 8: Physician Office Standardization

Background/Situation

In its effort to gain patient-centered medical home (PCMH)3 recognition, a health system leveraged its long-term Lean Sigma program and experience of process standardization to meet the NCQA4 requirements in an efficient and disciplined manner.

3. A team-based healthcare delivery model led by a primary care physician that provides comprehensive and continuous medical care to patients with the goal of obtaining maximized health outcomes.

4. The National Committee for Quality Assurance is an accrediting and standards-setting body for a number of healthcare-related organizations, including managed care and patient-centered medical homes.

Based on commitments to local employers, the timeline to achieve accreditation across eight physician practices was a very short seven months.

Approach

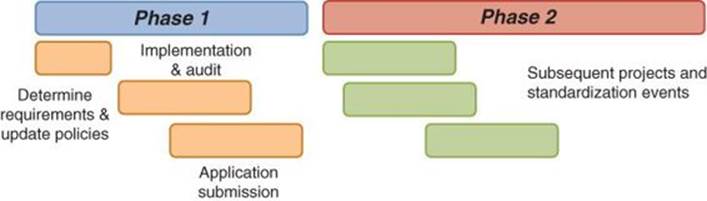

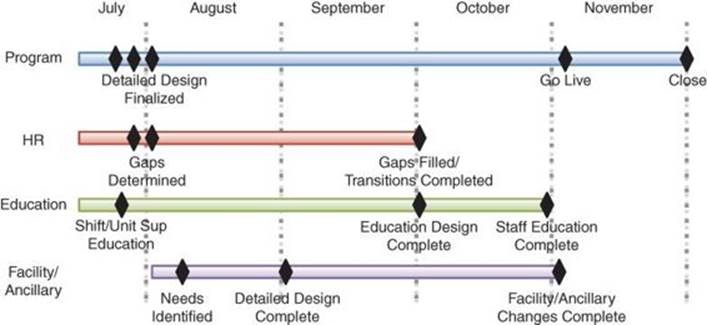

With such a short time frame to contend with, a typical standardization approach for each process would have taken more than two years, so it was deemed inappropriate. Instead, the route taken was a hybrid program approach, as shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.4 Phase approach to meeting NCQA requirements

In Phase 1, process change, led by a Black Belt, was driven across all eight practices directly from updating policies to the new requirements. During this phase, auditing of compliance with requirements was tracked, and a list of projects was identified for needed improvement in Phase 2. Once the practices were compliant with the required levels, the NCQA application was submitted.

Changes Made

The changes implemented all related directly to the NCQA standards and included access to medical records, access to a physician, as well as callbacks and other preventive measures for key population groups.

Results

All eight practices received recognition within the seven-month period, and seven out of the eight achieved the highest possible level. Based on the changes, appointment availability has increased significantly, and there has been a positive impact on preventive care related to callbacks for key areas such as mammography and colonoscopy.

Leadership Learning

Leadership learning from this project includes the following:

1. It was useful to see Lean Sigma as a tool to achieve strategic goals, for example, meeting NCQA accreditation and Meaningful Use.5

5. The Medicare and Medicaid electronic health record (EHR) Incentive Programs provide financial incentives for the meaningful use of certified EHR technology to improve patient care.

2. Lean Sigma Black Belts become very strong Project Leaders and are highly suitable for this kind of endeavor even though the approach was not classical Lean Sigma.

3. It was important to approach the issue not as a single project, but as a phased Tier 2 program6 of activity.

6. Please see Chapter 2, “Project Tiers.”

4. Standardization was useful once targets were met, to shore up performance gaps and to lock down the processes more fully.

5. Rather than solving the problems one office at a time, the solution was built once and then rolled out to all offices in a “pilot and proliferate” fashion.

Case 9: Surgery Capacity and Throughput

Background/Situation

A hospital’s main surgery was experiencing difficulties with on-time starts and throughput and had a substantial backlog in demand. Key surgeon groups were expressing frustration at not being able to get block7 or even schedule time and had indicated that their dissatisfaction might force them to conduct their procedures at other facilities.

7. Regular scheduled time set aside for a surgeon or surgery group.

Approach

To make a large enough change in short order, leadership elected to mobilize four Kaizen events run in parallel, scrutinizing each of the areas of patient intake, in-OR activity, post-surgery care, and OR room turns. Surgery leaders had heard of the Kaizen approach and felt it was an appropriate one, but the organization, early in its Lean Sigma deployment, hadn’t had any experience with leading such events.

This was a huge endeavor involving some 53 team members, Champions, and Process Owners, and each event was led by a separate (external) facilitator.

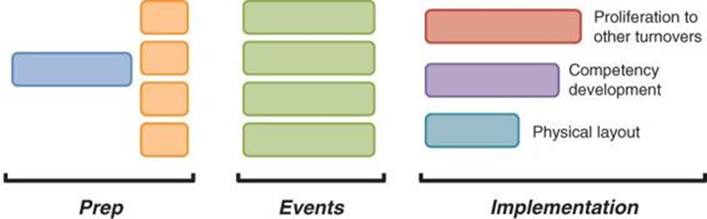

Prior to the events, preparation was done across all four events, first as a group and then with each event Team separately. Once the events were complete, a three-month rollout plan commenced to take, for example, learning from one room turnover type to other types in order of frequency (see Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5 Surgery Capacity and Throughput project timeline

Changes Made

Given that this was in effect just a very large Kaizen event, the sheer number of changes was large, but the level of sophistication was low—in Lean Sigma vernacular, “low tech, high touch,” but a lot of it. Most activity focused on basic flow and streamlining of the processes.

Results

Key turnover times were reduced substantially, for example, for going from one major case type to a different major case type; room turnover time was reduced from 42 minutes to 14 minutes.

The bigger result was that three key surgeons who had been threatening to leave stayed and the surgery protected its revenue base.

Leadership Learning

Leadership learning from this project includes the following:

1. Four events in parallel required senior executive-level commitment, a surgeon in every event, plus the chief of staff and anesthesiology floating among events.

2. Such longitudinal change often creates very high levels of stress (everyone’s cheese was moved at once), but even the simplest change management techniques pay dividends in such an environment.

3. To ensure that everyone was on the same page throughout the events, daily calibration meetings occurred across the events at the start of the day, at lunch, and at the end of each day.

4. As is common early in a Lean Sigma deployment, there was no performance management in place, and so it was initially tough to maintain performance. There was little in terms of basic operational thinking (solutions up to this point had mainly focused on just increasing staffing and fighting fires). The director and manager regularly spoke of being “hands-on” with much talk of needing a “high-performing team.”

5. Unfortunately, the surgery director baked in a lot of other unrelated solutions under the banner of the Kaizen work, which required a certain amount of damage control later.

Epilogue

The surgery director was subsequently “freed up to develop her career potential elsewhere.” The new director was very focused on operations management, visibility, and clarity of roles. With such stronger performance management, much of the benefit of the events only really came to fruition under the new culture; turnaround times met those demonstrated during the events, and the surgery volume increased.

Case 10: Emergency Department Throughput

Background/Situation

A medium-large health system had a large hospital-based ED with 50+ rooms catering to more than 80,000 visits per year. The department had long had patient satisfaction issues with long average length of stay and subsequently many patients being seen in the lobby area. ED leadership was considering spending substantial capital to revamp the lobby area to create additional treatment rooms but instead opted for a performance improvement effort first.

Approach

The endeavor was structured as a Tier 2 program of multiple sequenced events and projects. Given the complexity of the undertaking and multiple departments involved, a Steering Group was formed composed of all ancillary directors, ED leadership, finance, and ED physician leadership. The Steering Group championed the program as a whole and performed early work to identify the core processes and baseline performance. An initial assessment or “discovery” helped the Steering Group determine which core processes to tackle and in what order.

The first phase of the work, conducted over six months as shown in Figure 4.6, targeted six major ED processes, each one with an appropriately scoped Kaizen event. Subsequent phases included additional events, plus Lean Sigma projects.

Figure 4.6 Emergency Department Throughput program timeline

Changes Made

Each Phase 1 Kaizen focused on streamlining a core ED process, determined the best operating models to maximize capacity of supporting ancillary areas, and laid down clear role accountability.

One large event tackled the main ED operational (staffing) model as well as the primary ED flow.

Simple changes, such as those described in Case 1, allowed, for example, an ED-CT-focused event to create much increased CT capacity and so reduce ED-CT turnaround time.

Results

Phase 1 results were very encouraging:

1. The number of patients being seen in the lobby was reduced from 21% to 0%.

2. Patient satisfaction increased from the initial 15th percentile up to the 91st percentile.

3. ED-CT turnaround time was down more than 40%.

4. General X-ray turnaround time was down more than 40%.

5. ED-inpatient admit time was down 50%.

Leadership Learning

Key leadership learning from this program includes the following:

1. Rather than conducting multiple (seemingly unconnected) events or projects, it is better to approach the problem as a simple Tier 2 program. That way it becomes easier for departmental staff and the rest of the organization to understand and connect with the work.

2. It’s often useful to take a whole “value stream” approach rather than just focusing on (in this case) the ED. Key connected ancillary processes, such as imaging, are integral to the ED performance.

3. In such a complex environment, it’s very useful to set up a Steering Group, comprising all key leaders and physicians, to guide the program. The Steering Group continues to meet to guide overarching ED performance improvement and ensure that the ED meets scorecard and strategic goals.

4. It’s helpful to phase the work in meaningful sections so it doesn’t appear to be a never-ending effort.

5. All Phase 1 work was facilitated by an external resource, and internal capability was ramped up and used exclusively in Phase 2.

6. Almost constant communication was vital and included progress, success to date, and upcoming activities.

Case 11: Inpatient Placement

Background/Situation

With the advent of shifting patient population away from inpatient, a hospital was experiencing reduced volumes and utilization on its inpatient units, subsequent difficulties in staffing, and hence low and even negative margins for many DRGs.8

8. Diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) is a system used in the United States to classify hospital cases, with the intent to identify the “products” that a hospital provides. DRGs are used to determine how much Medicare pays the hospital for each “product,” with the reasoning that patients within each category are clinically similar and are expected to use the same level of hospital resources.

At the time (early in healthcare reform), inpatient nursing was heavily resistant to any financially driven change, and so the whole situation presented a difficult political and cultural challenge to the organization.

Approach

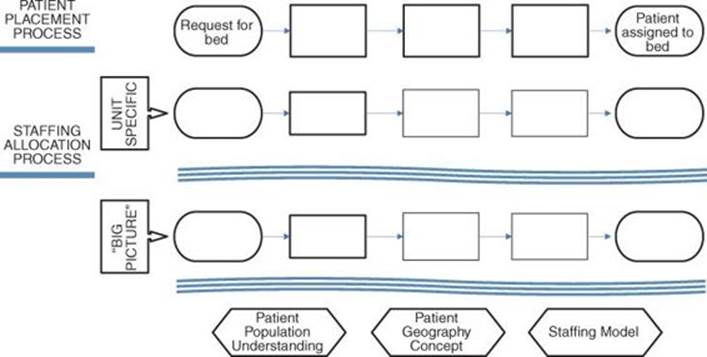

An endeavor to resolve the issues was complex. No single process could be tackled in isolation from the others, and so this was a classic example of a Tier 3 program (as introduced in Chapter 2), where each concept for multiple-component processes had to be designed and agreed upon in tandem, prior to any detailed design and implementation.

Figure 4.7 shows the primary processes and concepts that were redesigned. Given the political sensitivity and the sheer complexity of the endeavor, the project was co-led by a seasoned, highly respected internal (RN) Black Belt and the author as an external MBB.

Figure 4.7 Major processes and models redesigned during the project

Once the concepts were developed, a multifaceted implementation plan ensued, as shown in Figure 4.8. The MBB played the primary lead for the concept design work, while the Black Belt was the primary lead for the more significant volume of implementation work.

Figure 4.8 Inpatient Placement implementation plan

Changes Made

The most significant changes made in the project were first, how patients were grouped and where they were placed geographically (which units did what), and second, how the units were staffed in terms of their basic operating models. Based on these changes, one whole inpatient unit became a flex unit and closed during low census, only to open during peak demands.

Three major processes were also streamlined and had clear accountabilities set: the patient placement process, long-term staffing (staff budgeting, forecasting, and scheduling), and short-term staffing (flexing to demand).

Results

The flexing of units affected unit utilization substantially, taking it from 55% to more than 80%. The impact of this, along with the changes to staff planning and flexing, generated staffing savings of more than $600,000 per year.

Leadership Learning

Leadership learning from this project includes the following:

1. Some projects are well beyond a simple structure and have to be tackled as a fairly complex (Tier 3) program. The interconnectedness of the processes meant that they had to be redesigned together, rather than sequentially.

2. For politically or culturally sensitive projects, the use of seasoned and credible Project Leader(s) is crucial.

3. At the time, this type of project had never been conducted within any of the benchmark organizations contacted. Sometimes it’s important just to go ahead and cut new ground.

4. In such a complex process set there needed to be many Champions—the whole Executive Team in this case. To ensure that they moved forward together, all had to (literally) sign off on the concept.

Epilogue

This same successful project approach has since been repeated a number of times, for example, within a major healthcare system in a different state and also again in this same hospital to move to single-occupancy rooms.

Case 12: New Emergency Department Design

Background/Situation

A health system had struggled with a suboptimal footprint and layout of its ED in its main hospital for many years. The ED had been designed for fewer than 20,000 patients per year, but it was now seeing more than double that volume.

Leadership had opted to build a whole new ED rather than revamp the existing one. Initial schematics had been created, but concerns over designing the new ED with inherent process and flow weaknesses drove the ED leadership team to back up and commit time and effort prior to the architectural design to consider the process aspects of the new space in an effort to “build in leanness.”

Approach

Prior to the final schematic design phase, three additional phases were conducted, all led by Lean Sigma resources:

1. Voice of the Customer

2. ED process requirements analysis, to examine and understand core processes both within the ED, as well as those connecting the ED to ancillary areas

3. Layout concept design, taking into consideration output from the first two phases

Once the detailed schematics were finalized, multiple standardization events tackled the core ED processes to ensure that they were well integrated and took maximum advantage of the new layout.

Changes Made

Based on the work, a number of changes were made to the original designs, including the following:

• External perimeter changes to ensure close proximity of the main entrance to greeters

• The addition of rapid medical examination (RME) rooms in a suite of rapid access rooms close to the entrance

• Locating support rooms away from the main ED space to create a more compact environment

• Designing multiple hub spaces (nursing stations) instead of just one to bring staff closer to all treatment rooms (and thus patients)

Results

At the time of writing the construction has commenced for the new ED. The design received an overwhelming positive response from all audiences from the community to the Board of Trustees to the frontline staff.

Leadership Learning

Leadership learning from this project includes the following:

1. Lean Sigma process and flow considerations were combined into the more traditional design and build process.

2. Lean Sigma resources were used to lead, alongside architects and construction.

3. It’s best to get the design right the first time, instead of redesigning or compromising later.

4. Include VOC to ensure that nothing was missed.

5. Take advantage to advertise and brand the approach, to gain awareness and credibility in the community.