iOS 8 Programming Fundamentals with Swift (2014)

Part I. Language

Chapter 3. Variables and Simple Types

This chapter goes into detail about declaration and initialization of variables. It then discusses all the primary built-in Swift simple types. (I mean “simple” as opposed to collections; the primary built-in collection types are discussed at the end of Chapter 4.)

Variable Scope and Lifetime

Recall, from Chapter 1, that a variable is a named shoebox of a single well-defined type. Every variable must be explicitly and formally declared. To put an object into the shoebox, thus causing the variable name to refer to that object, you assign the object to the variable. (As we now know from Chapter 2, a function, too, has a type, and can be assigned to a variable.)

Aside from the convenience of giving a reference a name, a variable, by virtue of the place where it is declared, endows its referent with a particular scope (visibility) and lifetime; assigning something to a variable is a way of ensuring that it can be seen by code that needs to see it and that it persists long enough to serve its purpose.

In the structure of a Swift file (see Example 1-1), a variable can be declared virtually anywhere. It will be useful to distinguish several levels of variable scope and lifetime:

Global variables

A global variable, or simply a global, is a variable declared at the top level of a Swift file. (In Example 1-1, the variable one is a global.)

A global variable lives as long as the file lives. That means it lives forever. Well, not strictly forever, but as long as the program runs.

A global variable is visible everywhere — that’s what “global” means. It is visible to all code within the same file, because it is at top level, so any other code in the same file must be at the same level or at a lower, contained level of scope. Moreover, it is visible (by default) to all code within any other file in the same module, because Swift files in the same module can automatically see one another, and hence can see one another’s top levels.

Properties

A property is a variable declared at the top level of an object type declaration (an enum, struct, or class; in Example 1-1, the three name variables are properties). There are two kinds of properties: instance properties and static/class properties.

Instance properties

By default, a property is an instance property. Its value can differ for each instance of this object type. Its lifetime is the same as the lifetime of the instance. Recall from Chapter 1 that an instance comes into existence when it is created (by instantiation); the subsequent lifetime of the instance depends on the lifetime of the variable to which the instance itself is assigned.

Static/class properties

A property is a static/class property if its declaration is preceded by the keyword static or class. (I’ll go into detail about those terms in Chapter 4.) Its lifetime is the same as the lifetime of the object type. If the object type is declared at the top level of a file, or at the top level of another object type that is declared at top level, that means it lives forever (as long as the program runs).

A property is visible to all code inside the object declaration. For example, an object’s methods can see that object’s properties. Such code can refer to the property using dot-notation with self, and I always do this as a matter of style, but self can usually be omitted except for purposes of disambiguation.

An instance property is also visible (by default) to other code, provided the other code has a reference to this instance; in that case, the property can be referred to through dot-notation with the instance reference. A static/class property is visible (by default) to other code that can see the name of this object type; in that case, it can be referred to through dot-notation with the object type.

Local variables

A local variable is a variable declared inside a function body. (In Example 1-1, the variable two is a local variable.) A local variable lives only as long as its surrounding curly-brace scope lives: it comes into existence when the path of execution passes into the scope and reaches the variable declaration, and it goes out of existence when the path of execution comes to the end of (or otherwise leaves) the scope. Local variables are sometimes called automatic, to signify that they come into and go out of existence automatically.

A local variable can be seen only by subsequent code within the same scope (including a subsequent deeper scope within the same scope).

Variable Declaration

As I explained in Chapter 1, a variable is declared with let or var:

§ With let, the variable becomes a constant — its value can never be changed after the first assignment of a value (initialization).

§ With var, the variable is a true variable, and its value can be changed by subsequent assignment.

A variable’s type, however, can never be changed. A variable declared with var can be given a different value, but that value must conform to the variable’s type. Thus, when a variable is declared, it must be given a type, which it will have forever after. You can give a variable a type explicitly or implicitly:

Explicit variable type declaration

After the variable’s name in the declaration, add a colon and the name of the type:

var x : Int

Implicit variable type by initialization

If you initialize the variable as part of the declaration, and if you provide no explicit type, Swift will infer its type, based on the value with which it is initialized:

var x = 1 // and now x is an Int

It is perfectly possible to declare a variable’s type explicitly and assign it an initial value, all in one move:

var x : Int = 1

In that example, the explicit type declaration is superfluous, because the type (Int) would have been inferred from the initial value. Sometimes, however, providing an explicit type, even while also assigning an initial value, is not superfluous. Here are the main situations where that’s the case:

Swift’s inference would be wrong

A very common case in my own code is when I want to provide the initial value as a numeric literal. Swift will infer either Int or Double, depending on whether the literal contains a decimal point. But there are a lot of other numeric types! When I mean one of those, I will provide the type explicitly, like this:

let separator : CGFloat = 2.0

Swift warns if you don’t

When talking to Cocoa, you will often receive a value as an AnyObject (an Objective-C id; I’ll talk more about this in Chapter 4). If you use such a value to initialize a variable, the Swift compiler warns that this variable will be “inferred to have type AnyObject, which may be unexpected.” Warnings aren’t harmful, but I like to be rid of them, so I acknowledge to the compiler that I know this is an AnyObject, by declaring the type explicitly:

let n : AnyObject = arr[0] // arr is a Cocoa NSArray

Swift can’t infer the type

This situation arises for me most often when the initial value itself requires type inference on Swift’s part. In other words, in this situation, type inference runs the other way: the explicit variable type is what allows Swift to infer the type of the initial value. A very common case involves enums, which I haven’t discussed yet. This is legal but long-winded and repetitious:

let opts = UIViewAnimationOptions.Autoreverse | UIViewAnimationOptions.Repeat

I can make that code shorter and cleaner if Swift knows in advance that opts will be a UIViewAnimationOptions enum:

let opts : UIViewAnimationOptions = .Autoreverse | .Repeat

The programmer can’t infer the type

I frequently include a superfluous explicit type declaration for clarity — that is, as a kind of note to myself. Here’s an example from my own code:

let duration : CMTime = track.timeRange.duration

In that code, track is an AVAssetTrack. Swift knows perfectly well that the duration property of an AVAssetTrack’s timeRange property is a CMTime. But I don’t! In order to remind myself of that fact, I’ve shown the type explicitly.

Because explicit variable typing is possible, a variable doesn’t have to be initialized when it is declared. It is legal to write this:

var x : Int

Starting with Swift 1.2, that sort of thing is legal even for a constant:

let x : Int

Now x is an empty shoebox — an Int variable without a value. I strongly urge you, however, not to do that with a local variable if you can possibly avoid it. It isn’t a disaster — the Swift compiler will stop you from trying to use a variable that has never been assigned a value — but it’s not a good habit.

The exception that proves the rule is what we might call conditional initialization. Sometimes, we don’t know a variable’s initial value until we’ve performed some sort of conditional test. The variable itself, however, can be declared only once; so it must be declared in advance and conditionally initialized afterwards. We could give the variable a fake initial value as part of its declaration, but this might be misleading — and it won’t work if this variable is a constant, because giving it a fake initial value will prevent us from subsequently giving it a real value. So it is actually better to leave the variable momentarily uninitialized. Such code will have a structure similar to this:

let timed : Bool

if val == 1 {

timed = true

} else if val == 2 {

timed = false

}

A similar situation arises when a variable’s address is to be passed as argument to a function. Here, the variable must be declared and initialized beforehand, even if the initial value is fake. Recall this real-life example from Chapter 2:

var arrow = CGRectZero

var body = CGRectZero

CGRectDivide(rect, &arrow, &body, Arrow.ARHEIGHT, .MinYEdge)

After that code runs, our two CGRectZero values will have been replaced; they were just momentary placeholders, to satisfy the compiler.

Here’s a related situation. On rare occasions, you’ll want to call a Cocoa method that returns a value immediately and later uses that value in a function passed to that same method. For example, Cocoa has a UIApplication instance method declared like this:

func beginBackgroundTaskWithExpirationHandler(handler: () -> Void)

-> UIBackgroundTaskIdentifier

That function returns a number (a UIBackgroundTaskIdentifier is just an Int), and will later call the function passed to it (handler) — a function which will want to use the number that was returned at the outset. Swift’s safety rules won’t let you declare the variable that holds this number and use it in an anonymous function all in the same line:

let bti = UIApplication.sharedApplication()

.beginBackgroundTaskWithExpirationHandler({

UIApplication.sharedApplication().endBackgroundTask(bti)

}) // error: variable used within its own initial value

Therefore, you need to declare the variable beforehand; but then Swift has another complaint:

var bti : UIBackgroundTaskIdentifier

bti = UIApplication.sharedApplication()

.beginBackgroundTaskWithExpirationHandler({

UIApplication.sharedApplication().endBackgroundTask(bti)

}) // error: variable captured by a closure before being initialized

The solution is to declare the variable beforehand and give it a fake initial value as a placeholder:

var bti : UIBackgroundTaskIdentifier = 0

bti = UIApplication.sharedApplication()

.beginBackgroundTaskWithExpirationHandler({

UIApplication.sharedApplication().endBackgroundTask(bti)

})

NOTE

Properties of an object (at the top level of an enum, struct, or class declaration) can be initialized in the object’s initializer function rather than by assignment in their declaration. It is legal and common for both constant properties (let) and variable properties (var) to have an explicit type and no directly assigned initial value. I’ll have more to say about that in Chapter 4.

Computed Initializer

In the examples I’ve given so far, my variables have been initialized as literals or with a single line of code. Sometimes, however, you’d like to run several lines of code in order to compute a variable’s initial value. The simplest and most compact way to express this is with an anonymous function that you call immediately (see Define-and-Call).

When the variable you’re initializing is an instance property, a define-and-call anonymous function is usually the only way to compute the initial value with multiple lines of code. The reason is that, when you’re initializing an instance property, you can’t call an instance method, because there is no instance yet — the instance, after all, is what you are in the process of creating. You could call a top-level function, but that seems clumsy and inappropriate. Thus, you’ll use an anonymous function instead.

Here’s an example from my own code. In this class, there’s an image (a UIImage) that I’m going to need many times later on. It makes sense to create this image in advance as a constant instance property of the class. To create it means to draw it. That takes several lines of code. So I declare and initialize the property by defining and calling an anonymous function, like this (for my imageOfSize utility, see Chapter 2):

let ROWHEIGHT : CGFloat = 44 // global constant

class RootViewController : UITableViewController {

let cellBackgroundImage : UIImage = {

let f = CGRectMake(0,0,320,ROWHEIGHT)

return imageOfSize(f.size) {

UIColor.blackColor().setFill()

UIBezierPath(rect:f).fill()

// ... more drawing goes here ...

}

}()

// ... rest of the class declaration goes here ...

}

Computed Variables

The variables I’ve been describing so far in this chapter have all been stored variables. The shoebox analogy applies. The variable is a name, like a shoebox; a value can be put into the shoebox, by assigning to the variable, and it then sits there and can be retrieved later, by referring to the variable, for as long the variable lives.

Alternatively, a variable can be computed. This means that the variable, instead of having a value, has functions. One function, the setter, is called when the variable is assigned to. The other function, the getter, is called when the variable is referred to. Here’s some code illustrating schematically the syntax for declaring a computed variable:

var now : String { ![]()

get { ![]()

return NSDate().description ![]()

}

set { ![]()

println(newValue) ![]()

}

}

![]()

The variable must be a var (not a let). Its type must be declared explicitly. It is then followed immediately by curly braces.

![]()

The getter function is called get. Note that there is no formal function declaration; the word get is simply followed immediately by a function body in curly braces.

![]()

The getter function must return a value of the same type as the variable.

![]()

The setter function is called set. There is no formal function declaration; the word set is simply followed immediately by a function body in curly braces.

![]()

The setter behaves like a function taking one parameter. By default, this parameter arrives into the setter function body with the local name newValue.

Here’s some code that illustrates the use of a computed variable. You don’t treat it any differently than any other variable! To assign to the variable, assign to it; to use the variable, use it. Behind the scenes, though, the setter and getter functions are called:

now = "Howdy" // Howdy ![]()

println(now) // 2014-11-25 03:31:17 +0000 ![]()

![]()

Assigning to now calls its setter. The argument passed into this call is the assigned value; here, that’s "Howdy". That value arrives in the set function as newValue. Our set function prints newValue to the console.

![]()

Referring to now calls its getter. Our get function obtains the current date-time and translates it into a string, and returns the string. Our code then prints that string to the console.

Observe that when we set now to "Howdy" in the first line, the string "Howdy" wasn’t stored anywhere. It had no effect, for example, on the value of now in the second line. A set function can store a value, but it can’t store it in this computed variable; a computed variable isn’t storage! It’s a shorthand for calling its getter and setter functions.

There are a couple of variants on the basic syntax I’ve just illustrated:

§ The name of the set function parameter doesn’t have to be newValue. To specify a different name, put it in parentheses after the word set, like this:

set (val) { // now you can use "val" inside the setter function body

§ There doesn’t have to be a setter. If the setter is omitted, this becomes a read-only variable. Attempting to assign to it is a compile error. A computed variable with no setter is the primary way to create a read-only variable in Swift.

§ There must always be a getter! However, if there is no setter, the word get and the curly braces that follow it can be omitted. Thus, this is a legal declaration of a read-only variable:

§ var now : String {

§ return NSDate().description

}

A computed variable can be useful in many ways. Here are the ones that occur most frequently in my real programming life:

Read-only variable

A computed variable is the simplest way to make a read-only variable. Just omit the setter from the declaration. Typically, the variable will be a global variable or a property; there probably wouldn’t be much point in a local read-only variable.

Façade for a function

When a value can be readily calculated by a function each time it is needed, it often makes for simpler syntax to express it as a read-only calculated variable. Here’s an example from my own code:

var mp : MPMusicPlayerController {

get {

return MPMusicPlayerController.systemMusicPlayer()

}

}

It’s no bother to call MPMusicPlayerController.systemMusicPlayer() every time I want to refer to this object, but it’s so much more compact to refer to it by a simple name, mp. And since mp represents a thing, rather than the performance of an action, it’s much nicer for mp to appear as a variable, so that to all appearances it is the thing, rather than as a function, which returns the thing.

Façade for other variables

A computed variable can sit in front of one or more stored variables, acting as a gatekeeper on how those stored variables are set and fetched. This is comparable to an accessor function in Objective-C. In the extreme case, a public computed variable is backed by a private stored variable:

private var _p : String = ""

var p : String {

get {

return self._p

}

set {

self._p = newValue

}

}

That’s a silly example, because we’re not doing anything interesting with our accessors: we are just setting and getting the private stored variable directly, so there’s really no difference between p and _p. But based on that template, you could now add functionality so that something useful happens during setting and getting.

TIP

As the preceding example demonstrates, a computed instance property function can refer to other instance properties; it can also call instance methods. This is important, because in general the initializer for a stored property can do neither of those things. The reason this is legal for a computed property is that its functions won’t actually be called until after the instance exists.

Here’s a practical example of a computed variable used as a façade for storage. My class has an instance property holding a very large stored piece of data, which can alternatively be nil (it’s an Optional, as I’ll explain later):

var myBigDataReal : NSData! = nil

When my app goes into the background, I want to reduce memory usage (because iOS kills backgrounded apps that use too much memory). So I plan to save the data of myBigDataReal as a file to disk, and then set the variable itself to nil, thus releasing its data from memory. Now consider what should happen when my app comes back to the front and my code tries to fetch myBigDataReal. If it isn’t nil, we just fetch its value. But if it is nil, this might be because we saved its value to disk. So now I want to restore its value by reading it from disk, and then fetch its value. This is a perfect use of a computed variable façade:

var myBigData : NSData! {

set (newdata) {

self.myBigDataReal = newdata

}

get {

if myBigDataReal == nil {

// ... get a reference to file on disk, f ...

self.myBigDataReal = NSData(contentsOfFile: f)

// ... erase the file ...

}

return self.myBigDataReal

}

}

Setter Observers

Computed variables are not needed as a stored variable façade as often as you might suppose. That’s because Swift has another brilliant feature, which lets you effectively inject functionality into the setter of a stored variable — setter observers. These are functions that are called just before and just after other code sets a stored variable.

The syntax for declaring a variable with a setter observer is very similar to the syntax for declaring a computed variable; you can write a willSet function, a didSet function, or both:

var s : String = "whatever" { ![]()

willSet { ![]()

println(newValue) ![]()

}

didSet { ![]()

println(oldValue) ![]()

// self.s = "something else"

}

}

![]()

The variable must be a var (not a let). Its type must be declared explicitly. It can be assigned an initial value. It is then followed immediately by curly braces.

![]()

The willSet function, if there is one, is the word willSet followed immediately by a function body in curly braces. It is called when other code sets this variable, just before the variable actually receives its new value.

![]()

By default, the willSet function receives the incoming new value as newValue. You can change this name by writing a different name in parentheses after the word willSet. The old value is still sitting in the stored variable, and the willSet function can access it there.

![]()

The didSet function, if there is one, is the word didSet followed immediately by a function body in curly braces. It is called when other code sets this variable, just after the variable actually receives its new value.

![]()

By default, the didSet function receives the old value, which has already been replaced as the value of the variable, as oldValue. You can change this name by writing a different name in parentheses after the word didSet. The new value is already sitting in the stored variable, and thedidSet function can access it there. Moreover, it is legal for the didSet function to set the variable to a different value.

NOTE

Setter observer functions are not called when the variable is initialized or when the didSet function changes the variable’s value. That would be circular!

In practice, I find myself using setter observers, rather than a computed variable, in the vast majority of situations where I would have used a setter override in Objective-C. Here’s an example from Apple’s own code (the Master–Detail Application template) illustrating a typical use case — changing the interface as a consequence of a property being set:

var detailItem: AnyObject? {

didSet {

// Update the view.

self.configureView()

}

}

This is an instance property of a view controller class. Every time this property changes, we need to change the interface, because the job of the interface is, in part, to display the value of this property. So we simply call an instance method every time the property is set. The instance method reads the property’s value and sets the interface accordingly.

In this example from my own code, not only do we change the interface, but also we “clamp” the incoming value within a fixed limit:

var angle : CGFloat = 0 {

didSet {

// angle must not be smaller than 0 or larger than 5

if self.angle < 0 {

self.angle = 0

}

if self.angle > 5 {

self.angle = 5

}

// modify interface to match

self.transform = CGAffineTransformMakeRotation(self.angle)

}

}

TIP

A computed variable can’t have setter observers. But it doesn’t need them! There’s a setter function, so anything additional that needs to happen during setting can be programmed directly into that setter function.

Lazy Initialization

The term “lazy” is not a pejorative ethical judgment; it’s a formal description of an important behavior. If a stored variable is assigned an initial value as part of its declaration, and if it uses lazy initialization, then the initial value is not actually evaluated and assigned until actual code accesses the variable’s value.

There are three types of variable that can be initialized lazily in Swift:

Global variables

Global variables are automatically lazy. This makes sense if you ask yourself when they should be initialized. As the app launches, files and their top-level code are encountered. It would make no sense to initialize globals now, because the app isn’t even running yet. Thus global initialization must be postponed to some moment that does make sense. Therefore, a global variable’s initialization doesn’t happen until other code first refers to that global. Under the hood, this behavior is protected with dispatch_once; this makes initialization both singular (it can happen only once) and thread-safe.

Static properties

Static properties behave exactly like global variables, and for basically the same reason. (There are no stored class properties in Swift, so class properties can’t be initialized and thus can’t have lazy initialization.)

Instance properties

An instance property is not lazy by default, but it may be made lazy by marking its declaration with the keyword lazy. This property must be declared with var, not let. The initializer for such a property might never be evaluated, namely if code assigns the property a value before any code fetches the property’s value.

Lazy initialization is often used to implement singleton. Singleton is a pattern where all code is able to get access to a single shared instance of a certain class:

class MyClass {

static let sharedMyClassSingleton = MyClass()

}

Now other code can obtain a reference to MyClass’s singleton by saying MyClass.sharedMyClassSingleton. The singleton instance is not created until the first time other code says this; subsequently, no matter how many times other code may say this, the instance returned is always that same instance.

Now let’s talk about lazy initialization of instance properties. Why might you want this? One reason is obvious: the initial value might be expensive to generate, so you’d like to avoid generating it until and unless it is actually needed. But there’s another reason that might not occur to you at first, but that turns out to be even more important: a lazy initializer can do things that a normal initializer can’t. In particular, it can refer to the instance. A normal initializer can’t do that, because the instance doesn’t yet exist at the time that a normal initializer would need to run (ex hypothesi, we’re in the middle of creating the instance, so it isn’t ready yet). A lazy initializer, by contrast, won’t run until some time after the instance has fully come into existence, so referring to the instance is fine. For example, this code would be illegal if the arrow property weren’t declared lazy:

class MyView : UIView {

lazy var arrow : UIImage = self.arrowImage()

func arrowImage () -> UIImage {

// ... big image-generating code goes here ...

}

}

A very common idiom is to initialize a lazy instance property with a define-and-call anonymous function:

lazy var prog : UIProgressView = {

let p = UIProgressView(progressViewStyle: .Default)

p.alpha = 0.7

p.trackTintColor = UIColor.clearColor()

p.progressTintColor = UIColor.blackColor()

p.frame = CGRectMake(0, 0, self.view.bounds.size.width, 20)

p.progress = 1.0

return p

}()

There are some minor holes in the language: lazy instance properties can’t have setter observers, and there’s no lazy let (so you can’t readily make a lazy variable read-only). But these restrictions are not terribly serious, because lazy arguably isn’t doing very much that you couldn’t do with a calculated property backed by a stored property, as Example 3-1 shows.

Example 3-1. Implementing a lazy property by hand

private var lazyOncer : dispatch_once_t = 0

private var lazyBacker : Int = 0

var lazyFront : Int {

get {

dispatch_once(&lazyOncer) {

self.lazyBacker = 42 // expensive initial value

}

return self.lazyBacker

}

set {

dispatch_once(&self.lazyOncer) {}

// will set

self.lazyBacker = newValue

// did set

}

}

In Example 3-1, the idea is that only lazyFront is accessed publicly; lazyBacker is its underlying storage, and lazyOncer makes everything happen the right number of times. Since lazyFront is now an ordinary computed property, we can observe it during setting (put additional code into its setter function, at the points I’ve marked by “will set” and “did set”), or we can make it read-only (delete the setter entirely).

Built-In Simple Types

Every variable, and every value, must have a type. But what types are there? Up to this point, I’ve assumed the existence of some types, such as Int and String, without formally telling you about them. Here’s a survey of the primary simple types provided by Swift. (Collection types will be discussed at the end of Chapter 4.) I’ll also describe the instance methods, global methods, and operators applicable to these primary built-in types.

Bool

The Bool object type (a struct) has only two values, commonly regarded as true and false (or yes and no). You can represent these values using the literal keywords true and false, and it is natural to think of a Bool value as being either true or false:

var selected : Bool = false

In that code, selected is a Bool variable initialized to false; it can subsequently be set to false or true, and to no other values. Because of its simple yes-or-no state, a Bool variable of this kind is often referred to as a flag.

Cocoa functions very often expect a Bool parameter or return a Bool value. For example, when your app launches, Cocoa calls a method in your code declared like this:

func application(application: UIApplication,

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions launchOptions: [NSObject: AnyObject]?)

-> Bool

You can do anything you like in that function; often, you will do nothing. But you must return a Bool! And in real life, that Bool will always be true. A minimal implementation thus looks like this:

func application(application: UIApplication,

didFinishLaunchingWithOptions launchOptions: [NSObject: AnyObject]?)

-> Bool {

return true

}

A Bool is useful in conditions; as I’ll explain in Chapter 5, when you say if something, the something is the condition, and is a Bool — or an expression that evaluates to a Bool. For example, when you compare two values with the equality comparison operator ==, the result is a Bool —true if they are equal to each other, false if they are not:

if meaningOfLife == 42 { // ...

(I’ll talk more about equality comparison in a moment, when we come to discuss types that can be compared, such as Int and String.)

When preparing a condition, you will sometimes find that it enhances clarity to store the Bool value in a variable beforehand:

let comp = self.traitCollection.horizontalSizeClass == .Compact

if comp { // ...

Observe that, when employing that idiom, we use the Bool variable directly as the condition. It is silly — and arguably wrong — to say if comp == true, because if comp already means “if comp is true.” There is no need to test explicitly whether a Bool equals true or false; the conditional expression itself is already testing that.

Since a Bool can be used as a condition, a call to a function that returns a Bool can be used as a condition. Here’s an example from my own code. I’ve declared a function that returns a Bool to say whether the cards the user has selected constitute a correct answer to the puzzle:

func evaluate(cells:[CardCell]) -> Bool { // ...

Thus, elsewhere I can say this:

let solution = self.evaluate(cellsToTest)

if solution { // ...

And I can equally collapse that to a single line:

if self.evaluate(cellsToTest) { // ...

Unlike many computer languages, nothing else in Swift is implicitly coerced to or treated as a Bool. For example, in C, a boolean is actually a number, and 0 is false. But in Swift, nothing is false but false, and nothing is true but true.

The type name, Bool, comes from the English mathematician George Boole; Boolean algebra provides operations on logical values. Bool values are subject to these same operations:

!

Not. The ! unary operator reverses the truth value of the Bool to which it is applied as a prefix. If ok is true, !ok is false — and vice versa.

&&

Logical-and. Returns true only if both operands are true; otherwise, returns false. If the first operand is false, the second operand is not even evaluated (thus avoiding possible side effects).

||

Logical-or. Returns true if either operand is true; otherwise, returns false. If the first operand is true, the second operand is not even evaluated (thus avoiding possible side effects).

If a logical operation is complicated or elaborate, parentheses around subexpressions can help clarify both the logic and the order of operations.

Numbers

The main numeric types are Int and Double, meaning that, left to your own devices, these are the types you’ll use. Other numeric types exist mostly for compatibility with the C and Objective-C APIs that Swift needs to be able to talk to when you’re programming iOS.

Int

The Int object type (a struct) represents an integer between Int.max and Int.min inclusive. The actual values of those limits might depend on the platform and architecture under which the app runs, so don’t count on them to be absolute; in my testing at this moment, they are 263-1 and -263respectively (64-bit words).

The easiest way to represent an Int value is as a numeric literal. Any numeric literal without a decimal point is taken as an Int by default. Internal underscores are legal; this is useful for making long numbers readable. Leading zeroes are legal; this is useful for padding and aligning values in your code.

You can write a numeric literal using scientific notation. Everything after the letter e is the exponent of 10; for example, 3e2 is 3 times 102 (300).

You can write a numeric literal using binary, octal, or hexadecimal digits. To do so, start the literal with 0b, 0o, or 0x respectively. Thus, for example, 0x10 is decimal 16. You can use exponentiation here too; everything after the letter p is the exponent of 2. For example, 0x10p2 is decimal 64, because you are multiplying 16 by 22.

There are instance methods for converting to a different underlying byte-order representation (bigEndian, littleEndian, byteSwapped) but I have never had occasion to use them.

Double

The Double object type (a struct) represents a floating-point number to a precision of about 15 decimal places (64-bit storage).

The easiest way to represent a Double value is as a numeric literal. Any numeric literal containing a decimal point is taken as a Double by default. Internal underscores and leading zeroes are legal. Scientific notation is legal; everything after the letter e is the exponent of 10.

A Double literal may not begin with a decimal point! If the value to be represented is between 0 and 1, start the literal with a leading 0. (I stress this because it is significantly different from C and Objective-C.)

There’s a static property Double.infinity and an instance property isZero, among others.

Coercion

Coercion is the conversion of a value from one numeric type to another. Swift doesn’t really have explicit coercion, but it has something that serves the same purpose — instantiation. To convert an Int explicitly into a Double, instantiate Double with an Int in the parentheses. To convert a Double explicitly into an Int, instantiate Int with a Double in the parentheses; this will truncate the resulting value (everything after the decimal point will be thrown away):

let i = 10

let x = Double(i)

println(x) // 10.0, a Double

let y = 3.8

let j = Int(y)

println(j) // 3, an Int

When numeric values are assigned to variables or passed as arguments to a function, Swift will perform implicit coercion of literals only. This code is legal:

let d : Double = 10

But this code is not legal, because what you’re assigning is a variable (not a literal) of a different type; the compiler will stop you:

let i = 10

let d : Double = i // compile error

The solution is to coerce explicitly as you assign or pass the variable:

let i = 10

let d : Double = Double(i)

The same rule holds when numeric values are combined by an arithmetic operation. Swift will perform implicit coercion of literals only. The usual situation is an Int combined with a Double; the Int is treated as a Double:

let x = 10/3.0

println(x) // 3.33333333333333

But variables of different numeric types must be coerced explicitly so that they are the same type if you want to combine them in an arithmetic operation. Thus, for example:

let i = 10

let n = 3.0

let x = i / n // compile error; you need to say Double(i)

These rules are evidently a consequence of Swift’s strict typing; but (as far as I am aware) they constitute very unusual treatment of numeric values for a modern computer language, and will probably drive you mad in short order. The examples I’ve given so far were easily solved, but things can become more complicated if an arithmetic expression is longer, and the problem is compounded by the existence of other numeric types that are needed for compatibility with Cocoa, as I shall now proceed to explain.

Other numeric types

If you weren’t programming iOS — if you were using Swift in some isolated, abstract world — you could probably do all necessary arithmetic with Int and Double alone. Unfortunately, to program iOS you need Cocoa, which is full of other numeric types; and Swift has types that match every one of them. Thus, in addition to Int, there are signed integers of various sizes — Int8, Int16, Int32, Int64 — plus the unsigned integer UInt along with UInt8, UInt16, UInt32, and UInt64. In addition to Double, there is the lower-precision Float (32-bit storage, about 6 or 7 decimal places of precision) and the extended-precision Float80; plus, in the Core Graphics framework, CGFloat (whose size can be that of Float or Double, depending on the bitness of the surrounding architecture).

You may also encounter a C numeric type when trying to interface with a C API. These types, as far as Swift is concerned, are just type aliases, meaning that they are alternate names for another type; for example, a CDouble (corresponding to C’s double) is just a Double by another name, a CLong (C’s long) is an Int, and so on. Many other numeric type aliases will arise in various Cocoa frameworks; for example, an NSTimeInterval is merely a type alias for Double.

Here’s the problem. I have just finished telling you that you can’t assign, pass, or combine values of different numeric types using variables; you have to coerce those values explicitly to the correct type. But now it turns out that you’re being flooded by Cocoa with numeric values of many types! Cocoa will often hand you a numeric value that is neither an Int nor a Double — and you won’t necessarily realize this, until the compiler stops you dead in your tracks for some sort of type mismatch. You must then figure out what you’ve done wrong and coerce everything to the same type.

Here’s a typical example from one of my apps. We have a UIImage, we extract its CGImage, and now we want to express the size of that CGImage as a CGSize:

let mars = UIImage(named:"Mars")!

let marsCG = mars.CGImage

let szCG = CGSizeMake( // compile error

CGImageGetWidth(marsCG),

CGImageGetHeight(marsCG)

)

The trouble is that CGImageGetWidth and CGImageGetHeight return UInts, but CGSizeMake expects CGFloats. This is not an issue in C or Objective-C, where there is implicit coercion from the former to the latter. But in Swift, you have to coerce explicitly:

var szCG = CGSizeMake(

CGFloat(CGImageGetWidth(marsCG)),

CGFloat(CGImageGetHeight(marsCG))

)

Here’s another real-life example. A slider, in the interface, is a UISlider, whose minimumValue and maximumValue are Floats. In this code, s is a UISlider, g is a UIGestureRecognizer, and we’re trying to use the gesture recognizer to move the slider’s “thumb” to wherever the user tapped within the slider:

let pt = g.locationInView(s)

let percentage = pt.x / s.bounds.size.width

let delta = percentage * (s.maximumValue - s.minimumValue) // compile error

That won’t compile. pt is a CGPoint, and therefore pt.x is a CGFloat. Luckily, s.bounds.size.width is also a CGFloat, so the second line compiles — and percentage is now inferred to be a CGFloat. In the third line, however, we try to combine percentage withs.maximumValue and s.minimumValue — and they are Floats, not CGFloats. We must coerce explicitly:

let delta = Float(percentage) * (s.maximumValue - s.minimumValue)

The problem is particularly infuriating when Cocoa itself is responsible for the impedance mismatch. In Objective-C, you specify that a view controller’s view should appear in portrait orientation only like this:

-(NSUInteger)supportedInterfaceOrientations {

return UIInterfaceOrientationMaskPortrait;

}

However, it turns out that UIInterfaceOrientationMaskPortrait is an NSInteger, not an NSUInteger. In Objective-C, it’s fine to return an NSInteger where an NSUInteger is expected; implicit coercion is performed in good order. But in Swift, you can’t do that; the equivalent code doesn’t compile:

override func supportedInterfaceOrientations() -> Int {

return UIInterfaceOrientationMask.Portrait.rawValue // compile error

}

You have to perform the coercion explicitly:

override func supportedInterfaceOrientations() -> Int {

return Int(UIInterfaceOrientationMask.Portrait.rawValue)

}

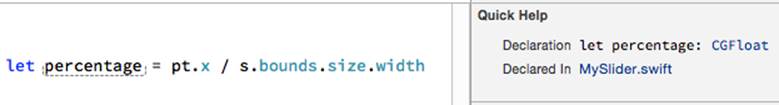

The good news here — perhaps the only good news — is that if you can get enough of your code to compile, Xcode’s Quick Help feature will tell you what type Swift has inferred for a variable (Figure 3-1). This can assist you in tracking down your issues with numeric types.

Figure 3-1. Quick Help displays a variable’s type

TIP

In the rare circumstance where you need to assign or pass an integer type where another integer type is expected and you don’t actually know what that other integer type is, you can get Swift to coerce dynamically by calling numericCast. For example, if i and j are previously declared variables of different integer types, i = numericCast(j) coerces j to the integer type ofi.

Arithmetic operations

Swift’s arithmetic operators are as you would expect; they are familiar from other computer languages as well as from real arithmetic:

+

Addition operator. Add the second operand to the first and return the result.

-

Subtraction operator. Subtract the second operand from the first and return the result. A different operator (unary minus), used as a prefix, looks the same; it returns the additive inverse of its single operand. (There is, in fact, also a unary plus operator, which returns its operand unchanged.)

*

Multiplication operator. Multiply the first operand by the second and return the result.

/

Division operator. Divide the first operand by the second and return the result.

WARNING

As in C, division of one Int by another Int yields an Int; any remaining fraction is stripped away. 10/3 is 3, not 3-and-one-third.

%

Remainder operator. Divide the first operand by the second and return the remainder. The result can be negative, if the first operand is negative; if the second operand is negative, it is treated as positive. Floating-point operands are legal.

Integer types can be treated as binary bitfields and subjected to binary bitwise operations:

&

Bitwise-and. A bit in the result is 1 if and only if that bit is 1 in both operands.

|

Bitwise-or. A bit in the result is 0 if and only if that bit is 0 in both operands.

^

Bitwise-or, exclusive. A bit in the result is 1 if and only if that bit is not identical in both operands.

~

Bitwise-not. Precedes its single operand; inverts the value of each bit and returns the result.

<<

Shift left. Shift the bits of the first operand leftward the number of times indicated by the second operand.

>>

Shift right. Shift the bits of the first operand rightward the number of times indicated by the second operand.

The bitwise-or operator arises surprisingly often in real life, because Cocoa often uses bits as switches when multiple options are to be specified simultaneously. For example, when specifying how a UIView is to be animated, you are allowed to pass an options: argument whose value comes from the UIViewAnimationOptions enumeration, whose definition (in Objective-C) begins as follows:

typedef NS_OPTIONS(NSUInteger, UIViewAnimationOptions) {

UIViewAnimationOptionLayoutSubviews = 1 << 0,

UIViewAnimationOptionAllowUserInteraction = 1 << 1,

UIViewAnimationOptionBeginFromCurrentState = 1 << 2,

UIViewAnimationOptionRepeat = 1 << 3,

UIViewAnimationOptionAutoreverse = 1 << 4,

// ...

};

Pretend that an NSUInteger is 8 bits (it isn’t, but let’s keep things simple and short). Then this enumeration means that (in Swift) the following name–value pairs are defined:

UIViewAnimationOptions.LayoutSubviews 0b00000001

UIViewAnimationOptions.AllowUserInteraction 0b00000010

UIViewAnimationOptions.BeginFromCurrentState 0b00000100

UIViewAnimationOptions.Repeat 0b00001000

UIViewAnimationOptions.Autoreverse 0b00010000

These values can be combined into a single value — a bitmask — that you pass as the options: argument for this animation. All Cocoa has to do to understand your intentions is to look to see which bits in the value that you pass are set to 1. So, for example, 0b00011000 would mean thatUIViewAnimationOptions.Repeat and UIViewAnimationOptions.Autoreverse are both true (and that the others, by implication, are all false).

The question is how to form the value 0b00011000 in order to pass it. You could form it directly as a literal and set the options: argument to UIViewAnimationOptions(0b00011000); but that’s not a very good idea, because it’s error-prone and makes your code incomprehensible. Instead, you use the bitwise-or operator to combine the desired options:

let opts : UIViewAnimationOptions = .Autoreverse | .Repeat

The bitwise-and operator arises less often; when it does, it’s used for the inverse of the operation we just performed. Cocoa hands you a bitmask, and you want to know whether a certain bit is set. In this example from a UITableViewCell subclass, the cell’s state comes to us as a bitmask; we want to know whether one particular bit is set:

override func didTransitionToState(state: UITableViewCellStateMask) {

let editing = UITableViewCellStateMask.ShowingEditControlMask.rawValue

if state.rawValue & editing != 0 {

// ... the ShowingEditControlMask bit is set ...

}

}

Integer overflow or underflow — for example, adding two Int values so as to exceed Int.max — is a runtime error (your app will crash). In simple cases the compiler will stop you, but you can get away with it easily enough:

let i = Int.max - 2

let j = i + 12/2 // crash

Under certain circumstances you might want to force such an operation to succeed, so special overflow/underflow methods are supplied. These methods return a tuple; I’ll show you an example even though I haven’t discussed tuples yet:

let i = Int.max - 2

let (j, over) = Int.addWithOverflow(i,12/2)

Now j is Int.min + 3 (because the value has wrapped around from Int.max to Int.min) and over is true (to report the overflow).

If you don’t care to hear about whether or not there was an overflow/underflow, special arithmetic operators let you suppress the error: &+, &-, &*.

You will frequently want to combine the value of an existing variable arithmetically with another value and store the result in the same variable. Remember that to do so, you will need to have declared the variable as a var:

var i = 1

i = i + 7

As a shorthand, operators are provided that perform the arithmetic operation and the assignment all in one move:

var i = 1

i += 7

The shorthand (compound) assignment arithmetic operators are +=, -=, *=, /=, %=, &=, |=, ^=, ~=, <<=, >>=.

It is often desirable to increase or decrease a numeric value by 1, so there are unary increment and decrement operators ++ and --. These differ depending on whether they are prefixed or postfixed. If prefixed (++i, --i) the value is incremented (or decremented), stored back in the same variable, and then used within the surrounding expression; if postfixed (i++, i--), the current value of the variable is used within the surrounding expression, and then the value is incremented (or decremented) and stored back in the same variable. Obviously, the variable must be declared with var.

Operation precedence is largely intuitive: for example, * has a higher precedence than +, so x+y*z multiplies y by z first, and then adds the result to x. Use parentheses to disambiguate when in doubt; for example, (x+y)*z performs the addition first.

Global functions include abs (absolute value), max, and min:

let i = -7

let j = 6

println(abs(i)) // 7

println(max(i,j)) // 6

Other mathematical functions, such as square roots, rounding, pseudorandom numbers, trigonometry, and so forth, come from the C standard libraries that are visible because you’ve imported UIKit. You still have to be careful about numeric types, and there is no implicit coercion, even for literals.

For example, sqrt expects a C double, which is a CDouble, which is a Double. So you can’t say sqrt(2); you have to say sqrt(2.0). Similarly, arc4random returns a UInt32. So if n is an Int and you want to get a random number between between 0 and n-1, you can’t sayarc4random()%n; you have to coerce the result of calling arc4random to an Int.

Comparison

Numbers are compared using the comparison operators, which return a Bool. For example, the expression i==j tests whether i and j are equal; when i and j are numbers, “equal” means numerically equal. So i==j is true only if i and j are “the same number,” in exactly the sense you would expect.

The comparison operators are:

==

Equality operator. Returns true if its operands are equal.

!=

Inequality operator. Returns false if its operands are equal.

<

Less-than operator. Returns true if the first operand is less than the second operand.

<=

Less-than-or-equal operator. Returns true if the first operand is less than or equal to the second operand.

>

Greater-than operator. Returns true if the first operand is greater than the second operand.

>=

Greater-than-or-equal operator. Returns true if the first operand is greater than or equal to the second operand.

Keep in mind that, because of the way computers store numbers, equality comparison of Double values may not succeed where you would expect. To test whether two Doubles are effectively equal, it can be more reliable to compare the difference between them to a very small value (usually called an epsilon):

let isEqual = abs(x - y) < 0.000001

String

The String object type (a struct) represents text. The easiest way to represent a String value is with a literal, which is delimited by double quotes:

let greeting = "hello"

A Swift string is thoroughly modern; under the hood, it’s Unicode, and you can include any character directly in a string literal. If you don’t want to bother typing a Unicode character whose codepoint you know, use the notation \u{...}, where what’s between the curly braces is two, four, or eight hex digits:

let checkmark = "\u{21DA}"

The backslash in that string representation is the escape character; it means, “I’m not really a backslash; I indicate that the next character gets special treatment.” Various nonprintable and ambiguous characters are entered as escaped characters; the most important are:

\n

A Unix newline character

\t

A tab character

\"

A quotation mark (escaped to show that this is not the end of the string literal)

\\

A backslash (escaped because a lone backslash is the escape character)

One of Swift’s coolest features is string interpolation. This permits you to embed any value that can be output with print (or println) inside a literal string as a string, even if it is not itself a string. The notation is escaped parentheses: \(...). For example:

var n = 5

let s = "You have \(n) widgets."

Now s is the string "You have 5 widgets." The example is not very compelling, because we know what n is and could have typed 5 directly into our string; but imagine that we don’t know what n is! Moreover, the stuff in escaped parentheses doesn’t have to be the name of a variable; it can be almost any expression that evaluates as legal Swift. If you don’t know how to add, this example is more compelling:

var m = 4

var n = 5

let s = "You have \(m + n) widgets."

One thing that can’t go inside escaped parentheses is double quotes. This is disappointing, but it’s not much of a hurdle; just assign to a variable and use the variable instead. For example, you can’t say this:

let ud = NSUserDefaults.standardUserDefaults()

let s = "You have \(ud.integerForKey("widgets")) widgets." // compile error

Escaping the double quotes doesn’t help. You have to write it as multiple lines, like this:

let ud = NSUserDefaults.standardUserDefaults()

let n = ud.integerForKey("widgets")

let s = "You have \(n) widgets.)"

To combine (concatenate) two strings, the simplest approach is to use the + operator (and its += assignment shortcut):

let s = "hello"

let s2 = " world"

let greeting = s + s2

This convenient notation is possible because the + operator is overloaded: it does one thing when the operands are numbers (numeric addition) and another when the operands are strings (concatenation). As I’ll explain in Chapter 5, all operators can be overloaded, and you can overload them to operate in some appropriate way on your own types.

As an alternative to +=, you can call the extend instance method:

var s = "hello"

let s2 = " world"

s.extend(s2) // or: s += s2

Another way of concatenating strings is with the join method. It takes an array (yes, I know we haven’t gotten to arrays yet) of strings to be concatenated, and is an instance method of the string that is to be inserted between all of them:

let s = "hello"

let s2 = "world"

let space = " "

let greeting = space.join([s,s2])

The comparison operators are also overloaded so that they all work with String operands, and work as you would expect. Two String values are equal (==) if they are, in the natural sense of the words, “the same text.” A String is less than another if it is alphabetically prior.

A few additional convenient instance methods and properties are provided. isEmpty returns a Bool reporting whether this string is the empty string (""). hasPrefix and hasSuffix report whether this string starts or ends with another string; for example, "hello".hasPrefix("h") istrue. The uppercaseString and lowercaseString properties provide uppercase and lowercase versions of the original string.

Coercion between a String and an Int is possible. To make a string that represents an Int, it is sufficient to use string interpolation; alternatively, use the Int as a String initializer, just as if you were coercing between numeric types:

let i = 7

let s = String(i)

Your string can also represent an Int in some other base; supply a radix: argument expressing the base:

let i = 31

let s = String(i, radix:16) // "1f"

A String that might represent an Int can be converted to the actual Int with the toInt instance method. The conversion might fail, because the String might not represent an Int; so the result is not an Int but an Optional wrapping an Int (I haven’t talked about Optionals yet, so you’ll have to trust me for now):

let s = "31"

let i = s.toInt() // Optional(31)

The length of a String, in characters, is given by the global count method:

let s = "hello"

let length = count(s) // 5

Why isn’t there simply a length property of a String? It’s because a String doesn’t really have a simple length. The String is stored as a sequence of Unicode codepoints, but multiple Unicode codepoints can combine to form a character; so, in order to know how many characters are represented by such a sequence, we actually have to walk through the sequence and resolve it into the characters that it represents.

You, too, can walk through a String. The simplest way is with the for...in construct (see Chapter 5). What you get when you do this are Character objects; I’ll talk more about Character objects later:

let s = "hello"

for c in s {

println(c) // print each Character on its own line

}

There is more to a Swift String object, but most of it would take us off into the weeds of Unicode representation, which in real life you won’t need to know about. The curious thing is that there aren’t more methods for standard string manipulation. How, for example, do you capitalize a string, or find out whether a string contains a given substring? Most modern programming languages have a compact, convenient way of doing things like that; Swift doesn’t.

The reason for this curious shortcoming appears to be that missing features are provided by the Foundation framework, to which you’ll always be linked in real life (importing UIKit imports Foundation). A Swift String is bridged to a Foundation NSString. This means that, to a large extent, Foundation NSString methods magically spring to life whenever you are using a Swift String. For example:

let s = "hello, world"

let s2 = s.capitalizedString // "Hello, World"

The capitalizedString property comes from the Foundation framework; it’s provided by Cocoa, not by Swift. It’s an NSString property; it appears tacked on to String “for free.” Similarly, here’s how to locate a substring of a string:

let s = "hello"

let range = s.rangeOfString("ell") // Optional(Range(1..<4))

I haven’t explained yet what an Optional is or what a Range is (I’ll talk about them later in this chapter), but that innocent-looking code has made a remarkable round-trip from Swift to Cocoa and back again: the Swift String s becomes an NSString, the NSString rangeOfString method is called, a Foundation NSRange struct is returned, and the NSRange is converted to a Swift Range and wrapped up in an Optional.

It will often happen, however, that you don’t want this round-trip conversion. For various reasons, you might want to stay in the Foundation world and receive the answer as a Foundation NSRange. To accomplish that, you have to cast your string explicitly to an NSString, using the asoperator (I’ll discuss casting formally in Chapter 4):

let s = "hello"

let range = (s as NSString).rangeOfString("ell") // (1,3), an NSRange

Here’s another example, also involving NSRange. Suppose you want to derive the string "ell" from "hello" by its range — the second, third, and fourth characters. Foundation’s NSString method substringWithRange: requires that you supply a range — meaning an NSRange. You can readily form the NSRange directly, using a Foundation function; but when you do, your code doesn’t compile:

let s = "hello"

let ss = s.substringWithRange(NSMakeRange(1,3)) // compile error

The reason for the compile error is that Swift has absorbed NSString’s substringWithRange:, and expects you to supply a Swift Range here. So you have to tell Swift to stay in the Foundation world, by casting:

let s = "hello"

let ss = (s as NSString).substringWithRange(NSMakeRange(1,3))

Swift also comes with a number of built-in general top-level functions that can be applied to strings. I’ve already mentioned count, which gives the length of the string in characters. contains returns a Bool, reporting whether a certain character (not substring) is found in a string:

let s = "howdy"

let ok = contains(s,"o") // true

Instead of a character, contains can take a function that takes a character and returns a Bool. This code reports whether the target string contains a vowel:

let s = "howdy"

let ok = contains(s){contains("aeiou",$0)} // true

find reports the index of a character (as an Optional):

let s = "howdy"

let ix = find(s,"o") // 1, wrapped in an Optional

All Swift indexes are numbered starting with 0, so 1 means the second element; thus, that code is telling you that "o" is found in "howdy" as its second character.

dropFirst and dropLast take a string and return (in effect) a new string without the first or last character, respectively. prefix and suffix extract the string of the given length from the start or end of the original string:

let s = "hello"

let s2 = prefix(s,4) // "hell"

split breaks a string up into an array of strings according to a function that takes a character and returns a Bool. In this example, I obtain all stretches of a string that don’t contain vowels or spaces:

let s = "hello world"

let arr = split(s, {contains("aeiou ",$0)}) // ["h", "ll", "w", "rld"]

Optional parameters allow split to do things such as limit the number of partitions:

let s = "hello world"

let arr = split(s, {contains("aeiou ",$0)}, maxSplit:1) // ["h", "llo world"]

Character

The Character object type (a struct) represents a single Unicode grapheme cluster — what you would naturally think of as one character of a string. A String object is formally a sequence of Character objects; that is why, as I mentioned earlier, you can walk through a string with for...in— what you are walking through are its Characters, one by one:

let s = "hello"

for c in s {

println(c) // print each Character on its own line

}

It isn’t common to encounter Character objects outside of some String of which they are a part. There isn’t even a way to write a literal Character. To make a Character from scratch, initialize it with a single-character String:

let c = Character("h")

(By the same token, you can initialize a String from a Character.) Alternatively, to make a Character from a Unicode codepoint integer, pass through the UnicodeScalar class:

let c = Character(UnicodeScalar(0x68))

Characters can be compared for equality; “less than” means what you would expect it to mean.

An array initialized with a String is an array of Character. A String can be initialized from an array of Character. Thus, it is possible to break a String into characters, manipulate the characters by manipulating the array, and reassemble into a new string:

let s = "hello"

var arr = Array(s)

arr.removeLast()

let s2 = String(arr) // "hell"

That’s not a very persuasive example, as we could have used the dropLast global function on the original string directly. However, a particularly nice thing about breaking a String into an array of Character is that the array is indexed by ordinary Int values. For example, what’s the second character of "hello"? Here’s one way to find out (recall that 1 means the second element):

let s = "hello"

var arr = Array(s)

let c = arr[1]

You can do the same thing directly with a String, but not so easily. This doesn’t compile:

let s = "hello"

let c = s[1] // compile error

The reason is that the indexes on a String are a special type, an Index. In particular, they are the type defined by the Index struct inside the String struct, which must thus be referred to from outside as String.Index. You can’t convert an Int to a String.Index. The only way to make aString.Index from scratch is to start with a String’s startIndex or endIndex. You can then call advance to derive the index you want:

let s = "hello"

let ix = s.startIndex

let ix2 = advance(ix,1)

let c = s[ix2] // "e"

The reason for this clumsy circumlocution is that Swift doesn’t know where the characters of a string actually are until it walks the string; calling advance is how you make Swift do that.

Once you’ve done the work to obtain a desired String.Index, you can use it to modify the string (provided your reference to the string is a var, of course). The splice(atIndex:) instance method inserts a string into a string:

var s = "hello"

let ix = s.startIndex

let ix2 = advance(ix,1)

s.splice("ey, h", atIndex: ix2) // "hey, hello"

Similarly, removeAtIndex deletes a single character (and returns that character). String manipulations involving longer stretches of the original string require use of a Range, which is the subject of the next section.

THE STRING–NSSTRING ELEMENT MISMATCH

Swift and Cocoa have different ideas of what the elements of a string are. The Swift conception involves characters. The NSString conception involves UTF-16 codepoints. Each approach has its advantages. The NSString way makes for great speed and efficiency in comparison to Swift, which must walk the string to investigate how the characters are constructed; but the Swift way gives what you would intuitively think of as the right answer. To emphasize this difference, a nonliteral Swift string has no length property; instead, its utf16 property exposes its codepoints, and the global count function then gives the same result as the NSString length property.

Fortunately, the element mismatch doesn’t arise very often in practice; but it can arise. Here’s a good test case:

let s = "Ha\u{030A}kon"

println(count(s)) // 5

let length = (s as NSString).length // or: let length = count(s.utf16)

println(length) // 6

We’ve created our string (the Norwegian name Håkon) using a Unicode codepoint that combines with the previous codepoint to form a character with a ring over it. Swift walks the whole string, so it normalizes the combination and reports 5 characters. Cocoa just sees at a glance that this string contains 6 16-bit codepoints.

Range

The Range object type (a struct) represents a pair of endpoints. There are two operators for forming a Range literal; you supply a start value and an end value, with one of the Range operators between them:

...

Closed interval operator. The notation a...b means “everything from a up to b, including b.”

..<

Half-open interval operator. The notation a..<b means “everything from a up to but not including b.”

Spaces around a Range operator are legal. A Range literal cannot be written backwards: the start value can’t be greater than the end value (the compiler won’t stop you, but you’ll crash at runtime).

The types of a Range’s endpoints will typically be some kind of number — most often, Ints:

let r = 1...3

If the end value is a negative literal, it has to be enclosed in parentheses:

let r = -1000...(-1)

A very common use of a Range is to loop through numbers with for...in:

for ix in 1 ... 3 {

println(ix) // 1, then 2, then 3

}

You can also use a Range’s contains instance method to test whether a value falls within given limits; a range used in this way is actually an Interval:

var ix = // ... an Int ...

if (1...3).contains(ix) { // ...

For purposes of testing containment, a Range’s endpoints can be Doubles:

var ix = // ... a Double ...

if (0.1...0.9).contains(ix) { // ...

Another common use of a Range is to index into a sequence. For example, here’s a way to get the second, third, and fourth characters of a String: we break the String into an array of Characters, and use a Range as an index into that array:

let s = "hello"

let arr = Array(s)

let result = arr[1...3]

let s2 = String(result)

You can also use a Range to index into a String directly, but it has to be a Range of String.Index, which, as I’ve already pointed out, is rather clumsy to obtain. One way to get one is to let Swift convert the NSRange that you get back from a Cocoa method call into a Swift Range for you:

let s = "hello"

let r = s.rangeOfString("ell") // a Swift Range (wrapped in an Optional)

You can also generate a pair of String.Index using advance from the string’s startIndex, as I showed earlier; you can then make a Range from them. Once you have a range of String.Index, some additional Swift String instance methods spring to life. For example, you can extract a substring by its range, using subscripting:

let s = "hello"

let ix1 = advance(s.startIndex,1)

let ix2 = advance(ix1,2)

let r = ix1...ix2

let s2 = s[r] // "ell"

Alternatively, you can call substringWithRange: on a Swift String without casting to an NSString:

let s = "hello"

let ix = advance(s.startIndex,1)

let ix2 = advance(ix,2)

let ss = s.substringWithRange(ix...ix2) // "ell"

You can also splice into a range, thus modifying the string:

var s = "hello"

let ix1 = advance(s.startIndex,1)

let ix2 = advance(ix1,2)

let r = ix1...ix2

s.replaceRange(r, with: "ipp") // s is now "hippo"

Similarly, you can delete a stretch of characters by specifying a range:

var s = "hello"

let ix1 = advance(s.startIndex,1)

let ix2 = advance(ix1,2)

let r = ix1...ix2

s.removeRange(r) // s is now "ho"

A Swift Range and a Cocoa NSRange are constructed very differently from one another. A Swift Range is defined by two endpoints. A Cocoa NSRange is defined by a starting point and a length. But you can coerce a Swift Range whose endpoints are Ints to an NSRange, and you can convert from an NSRange to a Swift Range with the toRange method (which returns an Optional wrapping a Range).

In our call to substringWithRange, as in our earlier call to rangeOfString:, Swift goes even further. It bridges between Range and NSRange for us, correctly taking account of the fact that Swift and Cocoa interpret characters and string length differently — and the fact that an NSRange’s values are Ints, while the endpoints of a Range describing a Swift substring are String.Index.

Tuple

A tuple is a lightweight custom ordered collection of multiple values. As a type, it is expressed by surrounding the types of the contained values with parentheses and separating them by commas. For example, here’s a declaration for a variable whose type is a tuple of an Int and a String:

var pair : (Int, String)

The literal value of a tuple is expressed in the same way — the contained values, surrounded with parentheses and separated by commas:

var pair : (Int, String)

pair = (1, "One")

Those types can be inferred, so there’s no need for the explicit type in the declaration:

var pair = (1, "One")

Tuples are a pure Swift language feature; they are not in any way compatible with Cocoa and Objective-C, so you’ll use them only for values that Cocoa never sees. Within Swift, however, they have many uses. For example, a tuple is an obvious solution to the problem that a method can return only one value; a tuple is one value, but it contains multiple values, so using a tuple as the return type of a method permits that method to return multiple values.

Tuples come with numerous linguistic conveniences. You can assign to a tuple of variable names as a way of assigning to multiple variables simultaneously:

var ix: Int

var s: String

(ix, s) = (1, "One")

That’s such a convenient thing to do that Swift lets you do it in one line, declaring and initializing multiple variables simultaneously:

let (ix, s) = (1, "One") // can use let or var here

Assigning variable values to one another through a tuple swaps them safely:

var s1 = "Hello"

var s2 = "world"

(s1, s2) = (s2, s1) // now s1 is "world" and s2 is "Hello"

TIP

There’s also a global function swap that swaps values in a more general way.

To ignore one of the assigned values, use an underscore to represent it in the receiving tuple:

let pair = (1, "One")

let (_, s) = pair // now s is "One"

The built-in Swift enumerate function lets you walk a sequence with for...in and receive, on each iteration, both a successive element and that element’s index number; this double result comes to you as — you guessed it — a tuple:

let s = "howdy"

for (ix,c) in enumerate(s) {

println("character \(ix) is \(c)")

}

I also pointed out earlier that numeric instance methods such as addWithOverflow return a tuple.

You can refer to the individual elements of a tuple directly, in two ways. The first way is by index number, using the literal number (not a variable value) as the name of a message sent to the tuple with dot-notation:

let pair = (1, "One")

let ix = pair.0 // now ix is 1

If your reference to a tuple isn’t a constant, you can assign into it by the same means:

var pair = (1, "One")

pair.0 = 2 // now pair is (2, "One")

The second way to access tuple elements is to give them names. The notation is like that of function parameters, and must appear as part of the explicit or implicit type declaration. Thus, here’s one way to establish tuple element names:

var pair : (first:Int, second:String) = (1, "One")

And here’s another way:

var pair = (first:1, second:"One")

The names are now part of the type of this value, and travel with it through subsequent assignments. You can then use them as literal message names, just like (and together with) the numeric literals:

var pair = (first:1, second:"One")

let x = pair.first // 1

pair.first = 2

let y = pair.0 // 2

You can assign from a tuple without names into a corresponding tuple with names (and vice versa):

var pair = (1, "One")

var pairWithNames : (first:Int, second:String) = pair

let ix = pairWithNames.first // 1

If you’re going to be using a certain type of tuple consistently throughout your program, it might be useful to give it a type name. To do so, use Swift’s typealias keyword. For example, in my LinkSame app I have a Board class describing and manipulating the game layout. The board is a grid of Piece objects. I needed a way to describe positions of the grid. That’s a pair of integers, so I define my own type as a tuple:

class Board {

typealias Slot = (Int,Int)

// ...

}

The advantage of that notation is that it now becomes easy to use Slots throughout my code. For example, given a Slot, I can now fetch the corresponding piece:

func pieceAt(p:Slot) -> Piece {

let (i,j) = p

// ... error-checking goes here ...

return self.grid[i][j]

}

The similarity between tuple element name syntax and function parameter lists is not a coincidence. A parameter list is a tuple! The truth is that every function takes one tuple parameter and returns one tuple. Thus, you can pass a single tuple to a function that takes multiple parameters. For example, suppose you have a top-level function like this:

func f (i1:Int, i2:Int) -> () {}

Then you can call it like this:

let p = (1,2)

f(p)

In that example, f is a top-level function, so it has no external parameter names. If a function does have external parameter names, you can pass it a tuple with named elements. So, again, let this be a top-level function:

func f2 (#i1:Int, #i2:Int) -> () {}

Then you can call it like this:

let p2 = (i1:1, i2:2)

f2(p2)

To sum up, there are actually four ways to pick up the individual element values from a tuple:

§ Assign to a tuple of variable names.

§ Use index numbers.

§ Use names; if the tuple lacks names, assign to a tuple of the same type with names.

§ Pass it to a function and pick up the elements as local parameter names.

Similarly, Void, the type of value returned by a function that doesn’t return a value, is actually a type alias for an empty tuple. That’s why it is also notated as ().

Optional

The Optional object type (an enum) wraps another object of any type. A single Optional object can wrap only one object. Alternatively, an Optional object might wrap no other object. This is what makes an Optional optional: it might wrap another object, but then again it might not. Think of an Optional as itself being a kind of shoebox — a shoebox which can quite legally be empty.

Let’s start by creating an Optional that does wrap an object. Suppose we want an Optional wrapping the String "howdy". One way to create it is with the Optional initializer:

var stringMaybe = Optional("howdy")

If we log stringMaybe to the console with println, we’ll see an expression identical to the corresponding initializer: Optional("howdy").

After that declaration and initialization, stringMaybe is typed, not as a String, nor as an Optional plain and simple, but as an Optional wrapping a String. This means that any other Optional wrapping a String, and only another Optional wrapping a String, can be assigned to it. This code is legal: