Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition (2014)

Part III. Mavericks Online

Chapter 10. Internet Setup & iCloud

As Apple’s programmers slogged away for months on the massive OS X project, there were areas where they must have felt like they were happily gliding on ice: networking and the Internet. For the most part, the Internet already runs on Unix, and hundreds of extremely polished tools and software chunks were already available.

There are all kinds of ways to get your Mac onto the Internet these days:

§ WiFi. Wireless hotspots, known as WiFi (or, as Apple used to call it, AirPort), are glorious conveniences, especially if you have a laptop. Without stirring from your hotel bed, you’re online at high speed. Sometimes for free.

§ Cable modems, DSL. Over half of the U.S. Internet population connects over higher-speed wires, using broadband connections that are always on: cable modems, DSL, or corporate networks. (These, of course, are often what’s at the other end of an Internet hotspot.)

§ Cellular modems. A few well-heeled individuals enjoy the go-anywhere bliss of USB cellular modems, which get them online just about anywhere they can make a phone call. These modems are offered by Verizon, Sprint, AT&T, and so on, and usually cost $60 a month.

NOTE

A MiFi is sort of a cellular modem, too. It’s a pocketable, battery-operated, portable hotspot. It converts the cellular signal into a WiFi signal, so up to five people can be online at once, while the MiFi itself sits happily in your pocket or laptop bag.

§ Tethering. Tethering is letting your cellphone act as a glorified Internet antenna for your Mac, whether connected by a cable or a Bluetooth wireless link. You pay your phone company extra for this convenience.

§ Dial-up modems. Their numbers are shrinking, but plenty of people still connect to the Internet using a modem that dials out over ordinary phone lines. The service is cheap, but the connection is slow.

This chapter explains how to set up each one of these. It also describes some of OS X’s offbeat Internet featurettes. It tackles Internet Sharing, which lets several computers in the same household share a single broadband connection; the system-wide Internet bookmarks known as Internet location files; and iCloud, Apple’s suite of free online syncing tools.

Network Central and Multihoming

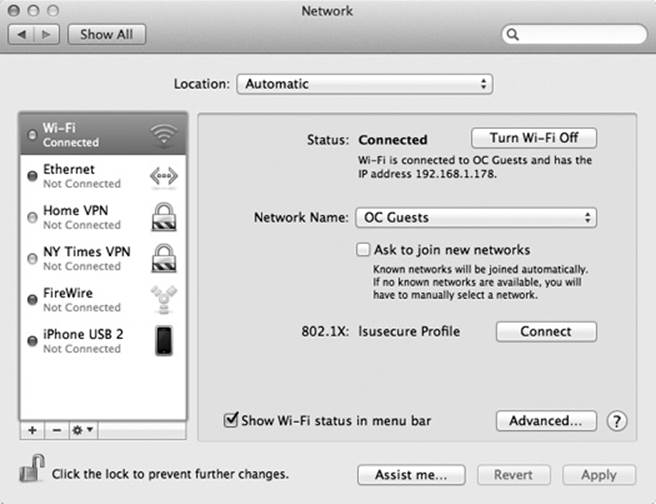

In this chapter, you’ll be spending a lot of time in the Network pane of System Preferences (Figure 10-1). (Choose ![]() →System Preferences; click Network.) This list summarizes the ways your Mac can connect to the Internet or an office network—Ethernet, WiFi, Bluetooth, cellular modem card, VPN, and so on.

→System Preferences; click Network.) This list summarizes the ways your Mac can connect to the Internet or an office network—Ethernet, WiFi, Bluetooth, cellular modem card, VPN, and so on.

Figure 10-1. You set up all your network connections here, and you can connect to and disconnect from all your networks here. The listed network connections are tagged with color-coded dots. A green dot means turned on and connected to a network; yellow means the connection is working but some other setting is wrong (for example, your Mac can’t get an IP address); red means there’s no connection, or you haven’t yet set up a connection.

Multihoming

The order of the network connections listed in the Network pane is important. That’s the sequence the Mac uses as it tries to get online. If one of your programs needs Internet access and the first method isn’t hooked up, then the Mac switches to the next available connection automatically.

In fact, OS X can maintain multiple simultaneous network connections—Ethernet, WiFi, dial-up, even FireWire—with a feature known as multihoming.

This feature is especially relevant for laptops. When you open your Web browser, your laptop might first check to see if it’s plugged into an Ethernet cable, which is the fastest, most secure type of connection. If there’s no Ethernet, then it looks for a WiFi network.

Here’s how to go about setting up the connection-attempt sequence you want:

1. Open System Preferences. Click the Network icon.

The Network Status screen (Figure 10-1) brings home the point of multihoming: You can have more than one network connection operating at once.

2. From the ![]() pop-up menu, choose Set Service Order.

pop-up menu, choose Set Service Order.

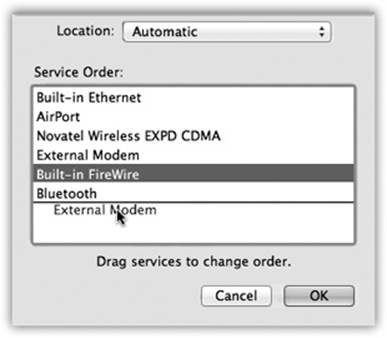

Now you see the display shown in Figure 10-2. It lists all the ways your Mac knows how to get online, or onto an office network.

Figure 10-2. The key to multihoming is sliding the network connection methods’ names up or down. Note that you can choose a different connection sequence for each location. (Locations are described later in this chapter.)

3. Drag the items up and down the list into priority order.

If you have a wired broadband connection, for example, you might want to drag Built-in Ethernet to the top of the list, since that’s almost always the fastest way to get online.

4. Click OK.

You return to the Network pane of System Preferences, where the master list of connections magically re-sorts itself to match your efforts.

Your Mac will now be able to switch connections even in real time, during a single Internet session. If lightning takes out your Ethernet hub in the middle of your Web surfing, your Mac will seamlessly switch to your WiFi network, for example, to keep your session alive.

All right, then: Your paperwork is complete. The following pages guide you through the process of setting up these various connections.

Broadband Connections

If your Mac is connected wirelessly or, um, wirefully to a cable modem, DSL, or office network, you’re one of the lucky ones. You have a high-speed broadband connection to the Internet that’s always available, always on. You never have to wait to dial.

Automatic Configuration

Most broadband connections require no setup whatsoever. Take a new Mac out of the box, plug in the Ethernet cable to your cable modem—or choose a wireless network from the ![]() menulet—and you can begin surfing the Web instantly.

menulet—and you can begin surfing the Web instantly.

That’s because most cable modems, DSL boxes, and wireless base stations use DHCP. It stands for dynamic host configuration protocol, but what it means is: “We’ll fill in your Network pane of System Preferences automatically.” (Including techie specs like IP address and DNS Server addresses.)

Manual Configuration

If, for some reason, you’re not able to surf the Web or check email the first time you try, it’s remotely possible that your broadband modem or your office network doesn’t offer DHCP. In that case, you may have to fiddle with the Network pane of System Preferences, preferably with a customer-support rep from your broadband company on the phone.

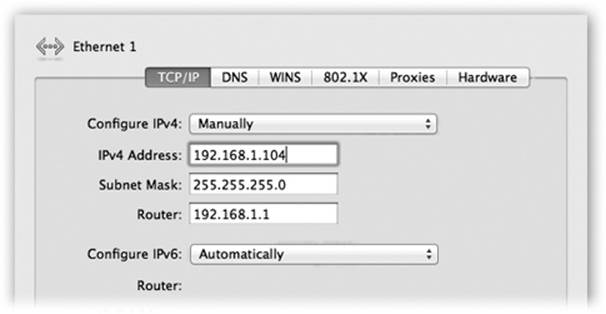

On the Network pane, click your Internet connection (Wi-Fi, Built-in Ethernet, cellular modem, whatever). Click Advanced; click TCP/IP. Now you see something like Figure 10-3. Don’t be alarmed by the morass of numbers and periods—it’s all in good fun. (If you find TCP/IP fun, that is.)

POWER USERS’ CLINIC: PPPOE AND DSL

If you have DSL service, you may be directed to create a PPPoE service. (You do that on the Network pane of System Preferences; click the ![]() button, choose PPPoE, select the connection you’re using to PPPoE, and then click Create.)

button, choose PPPoE, select the connection you’re using to PPPoE, and then click Create.)

It stands for PPP over Ethernet, meaning that although your DSL “modem” is connected to your Ethernet port, you still have to make and break your Internet connections manually, as though you had a dial-up modem.

Fill in the PPPoE dialog box as directed by your ISP (usually just your account name and password). From here on in, you start and end your Internet connections exactly as though you had a dial-up modem.

To get the information to fill in here, you can call your Internet provider (cable or phone company) for help—or you can copy your Windows configuration onto the Mac. Read on.

Figure 10-3. Here’s the setup for a cable-modem account with a static IP address, which means you have to type in all these numbers yourself.

Settings from Windows 2000, XP, Vista, Windows 7, or Windows 8

Your first task is to get to the Properties dialog box for your connection:

§ Windows 2000. Choose Start→Settings→Network and Dial-up Connections.

§ Windows XP. Choose Start→Control Panel. Open Network Connections.

§ Windows Vista. Choose Start→Control Panel. Open Network and Sharing Center. Click “Manage network connections.”

§ Windows 7. Choose Start→Control Panel. Open Network and Sharing Center. Click “Change adapter settings.”

§ Windows 8. At the desktop, right-click the lower-left corner of the screen; from the pop-up menu, choose Control Panel. Open Network and Sharing Center. Click “Change adapter settings.”

You wind up with a window full of icons that represent the various ways you can connect (3G Connection, Wireless Network Connection, Local Area Connection—that is, Ethernet cable—and so on).

Continue by right-clicking the icon for your broadband connection; from the shortcut menu, choose Properties. (In Windows Vista, you get an “Are you sure?” box at this point; click Continue.)

In the resulting dialog box, click the row that says “Internet Protocol (TCP/IP).”

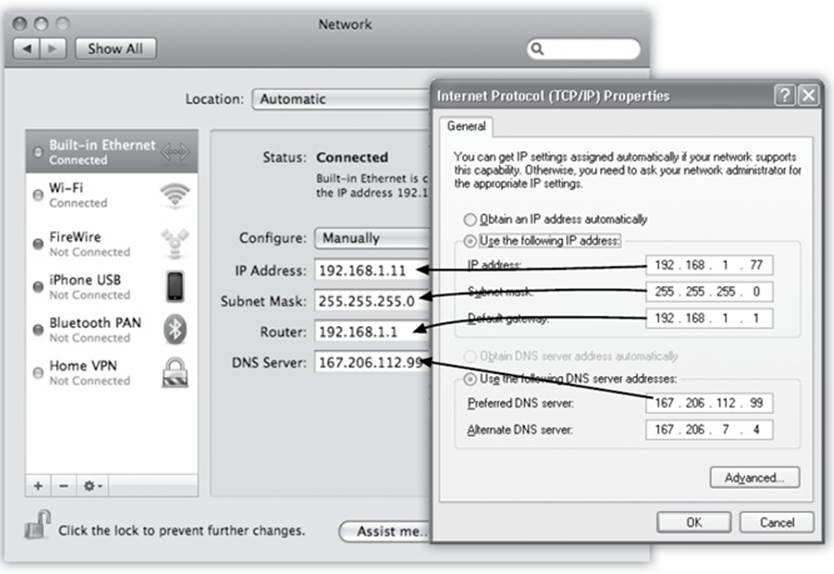

If the resulting screen says “Obtain an IP address automatically” (see Figure 10-4), then leave Using DHCP selected in the Mac’s Configure pop-up menu; your Mac should teach itself the correct settings automatically.

Figure 10-4. Here’s another way to fill in your Mac’s network settings: Copy them, blank by blank, from your old Windows PC.

If the Windows screen says, “Use the following IP address” instead, then select Manually from the Mac’s Configure pop-up menu, and copy the relevant numbers into the Mac’s Network panel (see Figure 10-4).

Similarly, if the Internet Protocol (TCP/IP Properties) dialog box says “Use the following DNS server addresses,” then type the numbers from the “Preferred DNS server” and “Alternate DNS server” boxes into the Mac’s DNS Servers text box. (Press Return to make a new line for the second number.)

NOTE

If your Mac plugs directly into the cable modem (that is, you don’t use a router), then you’ll have to turn the cable modem or DSL box off and then on again when you’ve switched from the PC to the Mac.

Settings from Windows 98, Windows Me

Choose Start→Settings→Control Panel. In the Control Panel window, double-click Network. Double-click the TCP/IP row that identifies how your PC is connected to the broadband modem. (It may say “TCP/IP→3Com Ethernet Adapter,” for example.)

Click the IP Address tab. If it says “Specify an IP address,” then copy the IP Address and Subnet Mask numbers into the same ones on the Mac’s Network panel. Then click the Gateway tab and copy the “Installed gateway” number into the Mac’s Router box.

Finally, click the DNS Configuration tab. Copy the strings of numbers you see here into the Mac’s DNS Servers text box. (Press Return to make a new line for the second number, if necessary.)

Applying the settings

That’s all the setup; on the Mac, in the Network pane of System Preferences, click Apply. If your settings are correct, you’re online, now and forever. You never have to worry about connecting or disconnecting.

Ethernet Connections

The beauty of Ethernet connections is that they’re super-fast and super-secure. No bad guys sitting across the coffee shop, armed with shareware “sniffing” software, can intercept your email and chat messages, as they theoretically can when you’re on wireless.

And 99 percent of the time, connecting to an Ethernet network is as simple as connecting the cable to the Mac. That’s it. You’re online, quickly and securely, and you never have to worry about connecting or disconnecting.

WiFi Connections

Your Mac can communicate with a wireless base station up to 300 feet away, much like a cordless phone. Doing so lets you surf the Web from your laptop in a hotel room, for example, or share files with someone across the building from you.

Chapter 15 has much more information about setting up a WiFi network. The real fun begins, however, when it comes time to join one.

Sometimes you just want to join a friend’s WiFi network. Sometimes you’ve got time to kill in an airport, and it’s worth a $7 splurge for half an hour. And sometimes, at some street corners in big cities, WiFi signals bleeding out of apartment buildings might give you a choice of several freehotspots to join.

Your Mac joins WiFi hotspots like this:

§ First, it sniffs around for a WiFi network you’ve used before. If it finds one, it connects quietly and automatically. You’re not asked for permission, a password, or anything else; you’re just online. (It’s that way, for example, when you come home with your laptop every day.) For details on this memorization feature, see the box on The Super-Secret Hotspot Management Box.

§ If the Mac can’t find a known hotspot, but it detects a new hotspot or two, a message appears on the screen, displaying their names. Double-click one to connect.

TIP

If you don’t want your Mac to keep interrupting you with its discoveries of new hotspots—it can get pretty annoying when you’re in a taxi driving through a city—you can shut them off. In System Preferences, click Network, click Wi-Fi, and then turn off “Ask to join new networks.”

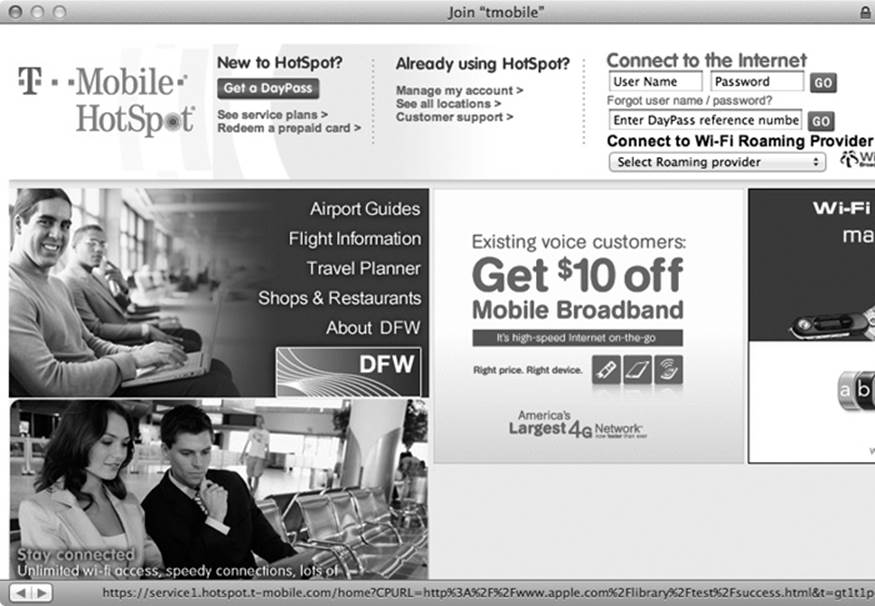

§ If you’re in the presence of a commercial hotspot—one that requires payment or reading some kind of insipid legal agreement—OS X opens a miniature Web page, shoving it right into your face, even if your Web browser isn’t open; see Figure 10-5.

Figure 10-5. OS X auto-opens a page like this whenever it senses that you’re in a commercial WiFi network, one that requires you to sign in. (That’s a big improvement from the old way, where you’d join a network and then have no clue that you wouldn’t be able to get any further until you opened up your Web browser to find that login screen.)

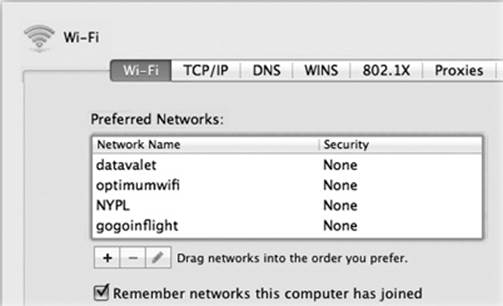

POWER USERS’ CLINIC: THE SUPER-SECRET HOTSPOT MANAGEMENT BOX

If you open System Preferences→Network, click Wi-Fi in the left-side list, and then click Advanced, you see the dialog box shown here. It lets you manage the list of WiFi hotspots that OS X has memorized on your travels.

For example, you can delete the old ones. Or you can drag the hotspots’ names up and down the list to establish a priority for making connections when more than one is available.

Ordinarily, OS X memorizes the names of the various hotspots you join on your travels. It’s kind of nice, actually, because it means you’re interrupted less often by the “Do you want to join?” box.

But if you’re alarmed at the massive list of hotspots OS X has memorized—for privacy reasons, say—here’s where you turn off “Remember networks this computer has joined.”

Finally, for added security on your Mac, you can turn on checkboxes that prevent the unauthorized from making changes (creating computer-to-computer networks, changing networks, turning WiFi on or off) without an administrator’s password.

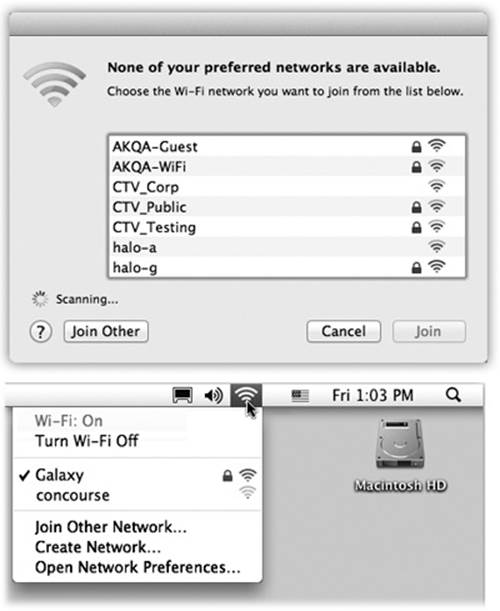

§ If you missed the opportunity to join a hotspot when the message appeared, or if you joined the wrong one or a non-working one, then you have another chance. You can always choose a hotspot’s name from the ![]() menulet, as shown in Figure 10-6. A

menulet, as shown in Figure 10-6. A ![]() icon indicates a hotspot that requires a password, so you don’t waste your time trying to join it (unless, of course, you have the password).

icon indicates a hotspot that requires a password, so you don’t waste your time trying to join it (unless, of course, you have the password).

TIP

It always takes a computer a few seconds—maybe 5 or 10—to connect to the Internet over WiFi. In OS X, the ![]() menulet itself pulses, or rather ripples, with a black-and-gray animation to let you know you’re still in the connection process. It’s an anti-frustration aid. (Oh, and also, each hotspot’s signal strength appears right in the menulet.)

menulet itself pulses, or rather ripples, with a black-and-gray animation to let you know you’re still in the connection process. It’s an anti-frustration aid. (Oh, and also, each hotspot’s signal strength appears right in the menulet.)

Figure 10-6. Top: Congratulations—your Mac has discovered new WiFi hotspots all around you! You even get to see the signal strength right in the menu. Double-click one to join it. But if you see a ![]() icon next to the hotspot’s name, beware: It’s been protected by a password. If you don’t know it, then you won’t be able to connect. Bottom: Later, you can always switch networks using the WiFi menulet.

icon next to the hotspot’s name, beware: It’s been protected by a password. If you don’t know it, then you won’t be able to connect. Bottom: Later, you can always switch networks using the WiFi menulet.

Before you get too excited, though, some lowering of expectations is in order. There are a bunch of reasons why your ![]() menulet might indicate that you’re in a hotspot but you can’t actually get online:

menulet might indicate that you’re in a hotspot but you can’t actually get online:

§ It’s locked. If there’s a ![]() next to the hotspot’s name in your

next to the hotspot’s name in your ![]() menulet, then the hotspot has been password protected. That’s partly to prevent hackers from “sniffing” the transmissions and intercepting messages, and partly to keep random passersby like you off the network.

menulet, then the hotspot has been password protected. That’s partly to prevent hackers from “sniffing” the transmissions and intercepting messages, and partly to keep random passersby like you off the network.

§ The signal isn’t strong enough. Sometimes the WiFi signal is strong enough to make the hotspot’s name show up in your ![]() menu but not strong enough for an actual connection.

menu but not strong enough for an actual connection.

§ You’re not on the list. Sometimes, for security, hotspots are rigged to permit only specific computers to join, and yours isn’t one of them.

§ You haven’t logged in yet. Commercial hotspots (the ones you have to pay for) don’t connect you to the Internet until you’ve supplied your payment details on a special Web page that appears automatically when you open your browser, as described below.

§ The router’s on, but the Internet’s not connected. Sometimes wireless routers are broadcasting, but their Internet connection is down. It’d be like a cordless phone that has a good connection back to the base station in the kitchen—but the phone cord isn’t plugged into the base station.

Commercial Hotspots

Choosing the name of the hotspot you want to join is generally all you have to do—if it’s a home WiFi network.

Unfortunately, joining a commercial WiFi hotspot—one that requires a credit card number (in a hotel room or an airport, for example)—requires more than just connecting to it. You also have to sign into it before you can send so much as a single email message.

To do that, open your Web browser—if, in fact, OS X doesn’t auto-open the sign-up screen. You’ll see the “Enter your payment information” screen either immediately or as soon as you try to open a Web page of your choice. (Even at free hotspots, you might have to click OK on a welcome page to initiate the connection.)

Supply your credit card information or (if you have a membership to this WiFi chain, like Boingo or T-Mobile) your name and password. Click Submit or Proceed, try not to contemplate how this $8 per hour is pure profit for somebody, and enjoy your surfing.

Cellular Modems

WiFi hotspots are fast and usually cheap—but they’re spots. Beyond 150 feet away, you’re offline.

No wonder laptop luggers across America are getting into cellular Internet services. All the big cellphone companies offer USB sticks that let your laptop get online at high speed anywhere in major cities. No hunting for a coffee shop; with a cellular Internet service, you can check your email while zooming down the road in a taxi. (Outside the metropolitan areas, you can still get online wirelessly, though much more slowly.)

Verizon, Sprint, and AT&T all offer cellular Internet networks with speeds approaching a cable modem’s. So why isn’t the world beating a path to this delicious technology’s door? Because it’s expensive—$60 a month on top of your phone bill.

To get online, insert the USB stick; it may take about 15 seconds for the thing to latch onto the cellular signal.

Now you’re supposed to make the Internet connection using the special “dialing” software provided by the cellphone company. Technically, though, you may not need it. You can start and stop the Internet connection using the commands in the ![]() menulet—no phone-company software required.

menulet—no phone-company software required.

Tethering

If you have an iPhone, Android phone, or another app phone, you don’t even need a cellular modem; you’ve already got one. Most app phones nowadays offer tethering, where the cellphone tunes into the Internet for the benefit of your laptop (or even your desktop computer). The phone connects to your laptop either with a USB cable or wirelessly (via Bluetooth or WiFi).

The nice part is that you can get online almost anywhere there’s cellphone coverage. The less-nice part is that the connection isn’t always blazing fast, and you have to pay your cellphone company for the privilege. (It’s usually $20 or $30 on top of your regular monthly phone plan; for that, you’re allowed to send and receive 2 gigabytes of data each month. If you go over the limit, you pay overage fees. Good luck figuring that out.)

Here’s a typical example: Suppose you have an iPhone. You open Settings→General→Network→Personal Hotspot. You turn it on. You assign a password to your private little hotspot. The iPhone asks how you’ll be connecting to the phone; let’s say you tap Wi-Fi.

Now, on your laptop, you choose your iPhone’s name from the ![]() menulet. You enter your hotspot password (just this time—later, your laptop will remember), and presto: Your laptop is online. A bright blue “Personal Hotspot: 1 Connection” banner appears on your iPhone to remind you, and your

menulet. You enter your hotspot password (just this time—later, your laptop will remember), and presto: Your laptop is online. A bright blue “Personal Hotspot: 1 Connection” banner appears on your iPhone to remind you, and your ![]() menulet changes to become the International Symbol for Apple Tethering:

menulet changes to become the International Symbol for Apple Tethering: ![]() .

.

Now, tethering eats up your phone’s battery like crazy; you’ll be lucky to get 3 hours out of it. So you probably shouldn’t count on watching Netflix on your laptop via your phone.

But for email, emergency Web checks, and other mobile crises, tethering is a convenient, useful feature. And when you’re on the road for a couple of weeks, it’s a heck of a lot cheaper than paying your hotel $13 a night for WiFi.

Dial-Up Modem Connections

If you ask Apple, dial-up modems are dead. Macs don’t even come with built-in modems anymore. You can get a non-Apple USB modem for $50, but clearly, Apple is trying to shove the trusty dial-up technology into the recycling bin.

Still, millions of people never got the memo. If you’re among them, then you need to sign up for Internet service. Once you’ve selected a service provider, you plug its settings into the Network pane of System Preferences. You get the necessary information directly from your ISP by consulting either its Web page, the instruction sheets that came with your account, or a help-desk agent on the phone.

Further details on OS X’s dial-up modem setup are in the free appendix to this chapter, “Setting Up a Dial-Up Connection.” It’s available on this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

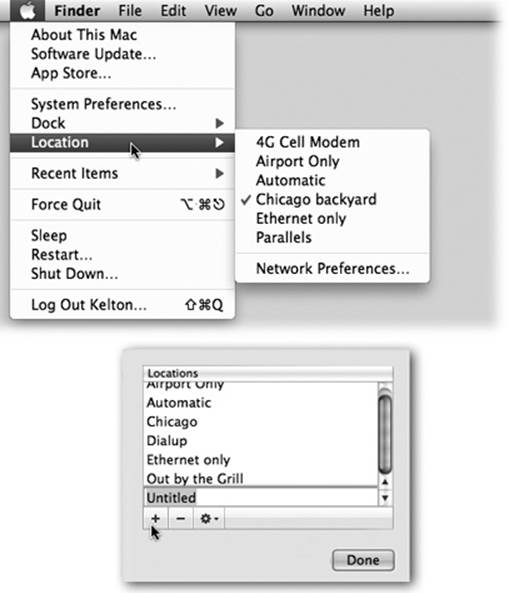

Switching Locations

If you travel with a laptop, you know the drill. You’re constantly opening up System Preferences→Network so you can switch between Internet settings: Ethernet at the office, WiFi at home. Or maybe you simply visit the branch office from time to time, and you’re getting tired of having to change the local access number for your ISP each time you leave home (and return home again).

Figure 10-7. The Location feature lets you switch from one “location” to another just by choosing its name—either from the ![]() menu (top) or from this pop-up menu in System Preferences (bottom). The Automatic location just means “the standard, default one you originally set up.” (Don’t be fooled: Despite its name, Automatic isn’t the only location that offers multihoming, described earlier in this chapter.)

menu (top) or from this pop-up menu in System Preferences (bottom). The Automatic location just means “the standard, default one you originally set up.” (Don’t be fooled: Despite its name, Automatic isn’t the only location that offers multihoming, described earlier in this chapter.)

The simple solution is the ![]() →Location submenu, which appears once you’ve set up more than one Location. As Figure 10-7 illustrates, all you have to do is tell it where you are. OS X handles the details of switching Internet connections.

→Location submenu, which appears once you’ve set up more than one Location. As Figure 10-7 illustrates, all you have to do is tell it where you are. OS X handles the details of switching Internet connections.

Creating a New Location

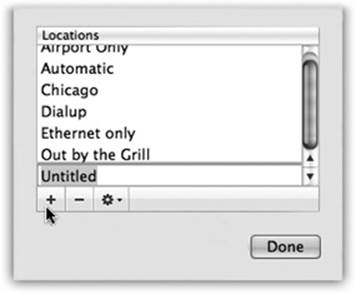

To create a Location, which is nothing more than a set of memorized settings, open System Preferences, click Network, and then choose Edit Locations from the Location pop-up menu. Continue as shown in Figure 10-8.

TIP

You can use the commands in the ![]() menu to rename or duplicate a Location.

menu to rename or duplicate a Location.

Figure 10-8. When you choose Edit Locations, this list of existing Locations appears; click the ![]() button. A new entry appears at the bottom of the list. Type a name for your new location, such as Chicago Office or Dining Room Floor.

button. A new entry appears at the bottom of the list. Type a name for your new location, such as Chicago Office or Dining Room Floor.

When you click Done, you return to the Network panel. Take this opportunity to set up the kind of Internet connection you use at the corresponding location, just as described on the first pages of this chapter.

If you travel regularly, you can build a list of Locations, each of which “knows” the way you like to get online in each city you visit.

A key part of making a new Location is putting the various Internet connection types (Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Modem, Bluetooth) into the correct order. Your connections will be slightly quicker if you give the modem connection priority in your Hotel setup, the WiFi connection priority in your Starbucks setup, and so on.

You can even turn off some connections entirely. For example, if you use nothing but a cable modem when you’re at home, you might want to create a location in which only the Ethernet connection is active. Use the Make Service Inactive command in the ![]() menu.

menu.

Conversely, if your laptop uses nothing but WiFi when you’re on the road, your Location could include nothing but the Wi-Fi connection. You’ll save a few seconds each time you try to go online, because your Mac won’t bother hunting for an Internet connection that doesn’t exist.

Making the Switch

Once you’ve set up your various Locations, you can switch among them using the ![]() →Location submenu, as shown in Figure 10-8. As soon as you do so, your Mac is automatically set to get online the way you like.

→Location submenu, as shown in Figure 10-8. As soon as you do so, your Mac is automatically set to get online the way you like.

TIP

If you have a laptop, create a connection called Offline. From the Show pop-up menu, choose Network Port Configurations; make all the connection methods in the list inactive. When you’re finished, you’ve got yourself a laptop that will never attempt to go online. It’s the laptop equivalent of Airplane Mode on a cellphone.

Internet Sharing

If you have cable modem or DSL service, you’re a very lucky individual. You get terrific Internet speed and an always-on connection. Too bad only one computer in your household or office can enjoy these luxuries.

It doesn’t have to be that way. You can spread the joy of high-speed Internet to every Mac (and PC) on your network in either of two ways:

§ Buy a router. A router is a little box, costing about $50, that connects directly to the cable modem or DSL box. In most cases, it has multiple Internet jacks so you can plug in several Macs, PCs, and/or wireless base stations. As a bonus, a router provides excellent security, serving as a firewall to keep out unsolicited visits from hackers on the Internet.

§ Use Internet Sharing. OS X’s Internet Sharing feature is the software version of a router: It distributes a single Internet signal to every computer on the network. But unlike a router, it’s free. You just fire it up on the one Mac that’s connected directly to the Internet—the gatewaycomputer.

But there’s a downside: If the gateway Mac is turned off or asleep, then the other machines can’t get online.

Most people use Internet Sharing to share a broadband connection like a cable modem or DSL. But there are other times when it comes in handy. If you have a cellular modem, for example, you might want to share its signal via WiFi so the kids in the backseat can get online with their iPod Touches. You could even share a tethered Bluetooth cellphone’s Internet connection with a traveling companion who needs a quick email check.

The only requirement: The Internet-connected Mac must have some other kind of connection (Ethernet, WiFi, Bluetooth, FireWire) to the Macs that will share the connection.

Turning On Internet Sharing

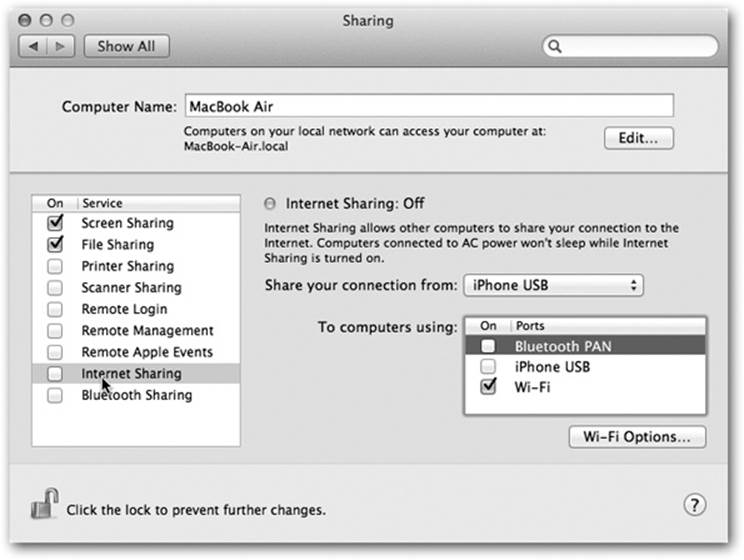

To turn on Internet Sharing on the gateway Mac, open the Sharing panel of System Preferences. Click Internet Sharing, as shown in Figure 10-9, but don’t turn on the checkbox yet.

Figure 10-9. Ka-ching! You and your buddy just saved money. In this example, an iPhone is getting this Mac online. But it’s sharing that Internet connection with other Macs via WiFi. They can get online, too, even though they’re not directly connected to the iPhone.

Before you do that, you have to specify (a) how the gateway Mac is connected to the Internet, and (b) how it’s connected to the other Macs on your network:

§ Share your connection from. Using this pop-up menu, identify how this Mac (the gateway machine) connects to the Internet—via Built-in Ethernet, Wi-Fi, cellular modem, or Bluetooth DUN (dial-up networking—that is, tethering to your cellphone).

§ To computers using. Using these checkboxes, specify how you want your Mac to rebroadcast the Internet signal to the others. (It has to be a different network channel. You can’t get your signal via WiFi and then pass it on via WiFi.)

NOTE

Which checkboxes appear here depends on which kinds of Internet connections are turned on in the Network pane of System Preferences. If the gateway Mac doesn’t have WiFi circuitry, for example, or if WiFi is turned off in the current configuration, then the Wi-Fi option doesn’t appear.

Now visit each of the other Macs on the same network. Open the Network pane of System Preferences. Select the network method you chose in the second step above: Wi-Fi, Built-in Ethernet, or FireWire. Click Apply.

If the gateway Mac is rebroadcasting using WiFi—by far the most common use of this feature—then you have one more step. In your ![]() menulet, you’ll see a strange new “hotspot” that wasn’t there before, bearing the name of the gateway Mac. (It might say, for example, “Casey’s MacBook Air.”) Choose its name to begin your borrowed Internet connection.

menulet, you’ll see a strange new “hotspot” that wasn’t there before, bearing the name of the gateway Mac. (It might say, for example, “Casey’s MacBook Air.”) Choose its name to begin your borrowed Internet connection.

As long as the gateway Mac remains on and online, both it and your other computers can get onto the Internet simultaneously, all at high speed, even Windows PCs. You’ve created a software base station. The Mac itself is now the transmitter for Internet signals to and from any other WiFi computers within range.

TIP

Now that you know how to let a wireless Mac piggyback on a wired Mac’s connection, you can let a wired Mac share a wireless connection, too. Suppose, for example, that you and a buddy both have laptops in a hotel lobby. You’re online, having paid $13 to use the hotel’s WiFi network. If you set up Internet Sharing appropriately, your buddy can connect to your Mac via an Ethernet cable or even a FireWire cable and surf along with you—no extra charge.

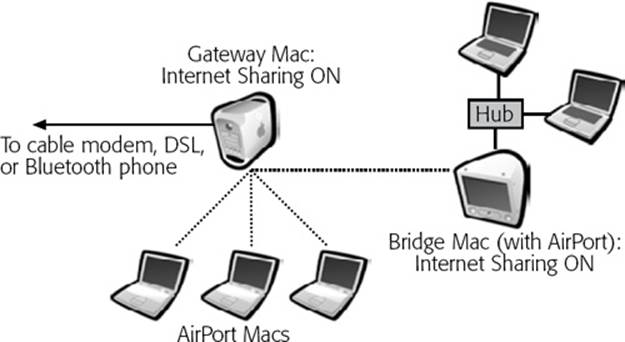

POWER USERS’ CLINIC: INTERNET SHARING AS A BRIDGE

Ordinarily, only one Mac has Internet Sharing turned on: the one that’s connected directly to the Internet.

But sometimes, you might want another Mac “downstream” to have it on, too. That’s when you want to bridge two networks.

Consider the setup shown here. There are really two networks: one that uses WiFi, and another connected to an Ethernet hub.

If you play your cards right, all these Macs can get online simultaneously, using a single Internet connection.

Set up the gateway Mac so that it’s a WiFi base station, exactly as described on these pages.

Start setting up the bridge Mac the way you’d set up the other WiFi Macs—with Wi-Fi selected as the primary connection method, and with Using DHCP turned on in the Network panel.

Then visit the bridge Mac’s Sharing panel. Turn on Internet Sharing here, too, but this time select “To computers using: Built-in Ethernet.”

The bridge Mac is now on both networks. It uses the WiFi connection as a bridge to the gateway Mac and the Internet—and its Ethernet connection to share that happiness with the wired Macs in its own neighborhood.

iCloud

Apple’s free iCloud service—formerly MobileMe, formerly .Mac, formerly iTools—offers a long list of very useful features. You don’t have to sign up, but you owe it to yourself to know what’s available; you sacrifice a lot of convenience if you don’t.

What iCloud Gives You

So what is iCloud? Mainly, it’s these things:

§ A synchronizing service. It keeps your calendar, address book, documents, reminders, notes, and photos updated and identical on all your gadgets: Mac, PC, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch.

§ An online locker. Anything you buy from Apple—music, TV shows, ebooks, and apps—is stored online, for easy access at any time. For example, whenever you buy a song or a TV show from the online iTunes store, it appears automatically on all your i-gadgets and computers. Your photos are stored online, too.

§ Back to My Mac. This option to grab files from one of your other Macs across the Internet isn’t new, but it survives in iCloud. See Screen sharing with Back to My Mac.

§ Find My iPhone—and Mac. Find My iPhone is one of iCloud’s greatest features. It pinpoints the current location of your iPhone or iPad on a map. In other words, it’s great for helping you find your i-gadget if it’s been stolen or lost.

You can also make your lost gadget start making a loud pinging sound for a couple of minutes by remote control—even if it was set to Vibrate mode. That’s brilliantly effective when your phone has slipped under the couch cushions. In dire situations, you can even erase the phone by remote control, preventing sensitive information from falling into the wrong hands.

This feature can find your Mac, too. That might seem like a silly idea; how often do you misplace your iMac? But remember that 75 percent of all computers Apple sells are laptops.

§ Automatic Backup. iCloud can back up your iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch—completely, automatically, and wirelessly (over WiFi, not over cellular connections). It’s a quick backup, since iCloud backs up only the changed data.

If you ever want to set up a new i-gadget, or if you want to restore everything to an existing one, life is sweet. Once you’re in a WiFi hotspot, all you have to do is re-enter your Apple ID and password in the setup assistant that appears when you turn the thing on. Magically, your gadget is refilled with everything that used to be on it.

NOTE

Well, almost everything. You get back everything you’ve bought from Apple (music, apps, books); photos and videos in your Camera Roll; settings, including the layout of your Home screen; text messages; and ringtones. Your mail and anything that came to the gadget from your computer (like music from iTunes and photos from iPhoto) have to be reloaded.

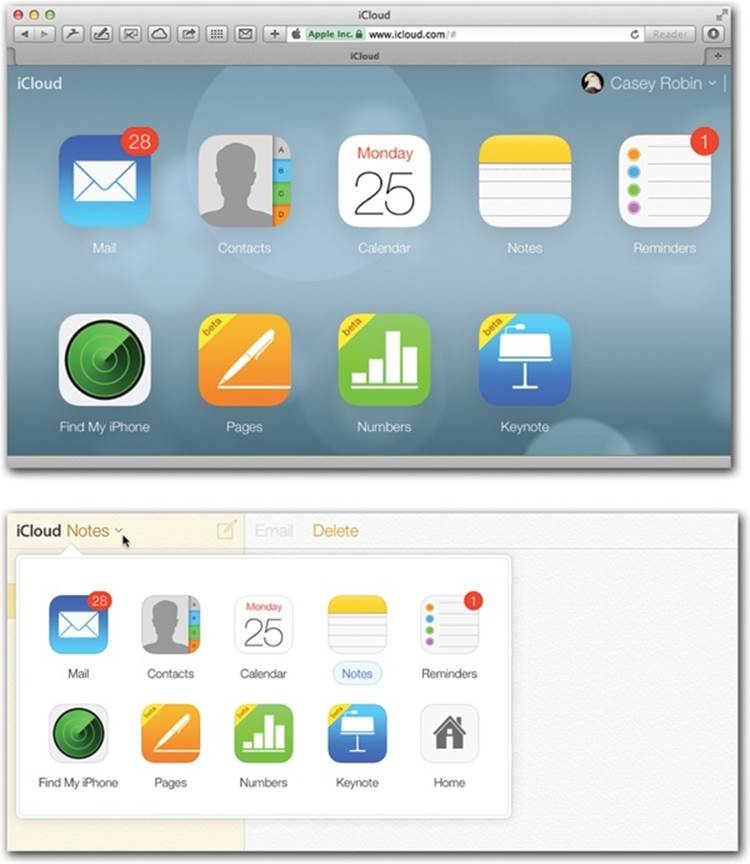

Much of this is based on the central Web site www.icloud.com (Figure 10-10).

TIP

You can get iCloud on your Windows PC, too, and enjoy all of its features there—including syncing to Microsoft Outlook. Just install the free iCloud control panel for Windows, which is available at www.apple.com/icloud/setup/pc.html.

Figure 10-10. Top: Here’s the iCloud home screen, showing the major online features of this service. All of this stuff, of course, is an online mirror of what’s on your Mac. Bottom: Once you’re in one of the modules—Mail, Calendar, Notes, or whatever—you can switch among iCloud features using the ![]() that always appears in the upper-left corner.

that always appears in the upper-left corner.

Starting Up iCloud

Your iCloud adventure begins in System Preferences; click the iCloud icon. Enter your Apple ID and password (DVD Player). Click Sign In.

Now the preference pane invites you to turn on two of the biggest iCloud features:

§ Use iCloud for contacts, calendars, reminders, notes, and Web bookmarks. It’s hard to imagine that you’d turn off this option—it’s the single most important iCloud feature—but this is the on/off switch if you’re some kind of heretic.

§ Use Find My Mac. This is the “Find my lost laptop on a map” feature described on Find My Mac, Find My iPhone. Click Next and then confirm that you really want to use Find My Mac.

At this point, you may be warned that to use iCloud password syncing, your Mac account needs a password, and you’re given the chance to make one up.

At last you arrive at the screen you’ll see when you open the iCloud pane on System Preferences from now on (Figure 10-11).

Figure 10-11. The headquarters of iCloud’s features. You’ll find a nearly identical panel on your iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch (in Settings→iCloud).

Let your grand tour of iCloud’s motley features begin.

iCloud Sync

For many people, this may be the killer app for iCloud right here: The icloud.com Web site, acting as the master control center, can keep multiple Macs, Windows PCs, and iPhones/iPads/iPod Touches synchronized. There’s both a huge convenience factor—all your stuff is always on all your gadgets—and a safety/backup factor, since you have duplicates everywhere.

It works by storing the master copies of your stuff—email, notes, contacts, calendars, Web bookmarks, and documents—on the Web. (Or “in the cloud,” as the product managers would say.)

Whenever your computers or i-gadgets are online, they connect to the mother ship and update themselves. Edit an address on your iPhone, and you’ll find the same change in Contacts (on your Mac) and Outlook (on your PC). Send an email reply from your PC at the office, and you’ll find it in your Sent Mail folder on the Mac at home. Add a Web bookmark anywhere and find it everywhere else. Edit a spreadsheet in Numbers on your iPad, and find the same numbers updated on your Mac.

Actually, there’s another place where you can work with your data: on the Web. At www.icloud.com, you can log in to find Web-based clones of Calendar, Contacts, Mail, Notes, Reminders, and iWork.

To set up syncing, open System Preferences→iCloud. Turn on the checkboxes of the stuff you want to be synchronized all the way around:

§ Mail. “Mail” refers to your actual email messages, plus your account settings and preferences from OS X’s Mail program.

§ Contacts. This is a big one. There’s nothing as exasperating as realizing that the address book you’re consulting on your home Mac is missing somebody you’re sure you entered—on your computer at work. This option keeps all your Macs’ contacts synchronized. Delete a phone number at work, and you’ll find it deleted on your Mac at home, too.

§ Calendars. Enter an appointment on your iPhone, and you’ll find the calendar updated everywhere else, like in the Mac’s Calendar program.

§ Reminders. Make a reminder for yourself on the Mac—using the built-in Reminders app—and have it remind you later on your phone. Or consult your to-do list from any computer. These tricks are thanks to the Reminders module at www.icloud.com.

UP TO SPEED: THE PRICE OF FREE

A free iCloud account gives you 5 gigabytes of online storage. That may not sound like much, especially when you consider how big some music files, photo files, and video files are.

Fortunately, nothing you buy from Apple—including music, apps, books, and TV shows—counts against that 5-gigabyte amount. Neither do the photos in your Photo Stream.

So what’s left? Just email, settings, documents, and pictures you take with your iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch—all stuff that doesn’t take up much space.

You can, of course, expand your storage if you find 5 gigs constricting—for $2 a gigabyte a year. So you’ll pay $20, $40, or $100 a year for an extra 10, 20, or 50 gigs. You can upgrade your storage right from your i-gadget or computer.

§ Notes. These are the notes you enter in the Notes program. They sync across all your Apple gadgets—and, as with Reminders, they’re available for inspection online.

§ Safari. If a Web site is important enough to merit bookmarking while you’re using your laptop, why shouldn’t it also show up in the Bookmarks menu on your desktop Mac at home, in your iPhone, or on your PC at work? This option syncs your Safari Reading List, too, and also iCloud Tabs (whatever tabs and windows were most recently open on your other Apple gadgets and Macs).

§ iCloud Keychain. It’s been many years in arriving, but it’s awesome: Safari can memorize all those passwords you have to enter for Web sites—and even sync them to your phone, tablet, and other Macs. It can also memorize your credit cards and your Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn account information. Details are on Organizing Bookmarks in the Editor.

§ Photo Stream is described in the next section.

§ Documents and Data. Numbers, Pages, and Keynote are available for Mac, iPhone/iPod Touch, and iPad. Therefore, you can store their documents online, where they’re accessible from any of your Apple machines. You can also have your Preview, TextEdit, and Automator documents stored online; use the Options button here to specify which document types you want synced.

§ Back to My Mac. See Screen sharing with Back to My Mac for details.

§ Find My Mac. Read on.

To set up syncing, turn on the checkboxes for the items you want synced.

NOTE

You may notice that there are no checkboxes here for syncing stuff you buy from Apple, like books, movies, apps, and music. They’re not so much synced as they are stored for you online. You can download them at any time to any of your machines.

After the first sync with the first machine, you can turn on the checkboxes on the other computers and gadgets, too, in effect telling them to participate in the great data-sharing experiment.

Photo Stream

Every time a new photo enters your life—when you take a picture with an i-gadget, for example, or import one onto your computer—it gets added to your Photo Stream. In other words, it appears automatically on all your other iCloud machines. Here’s where to find them:

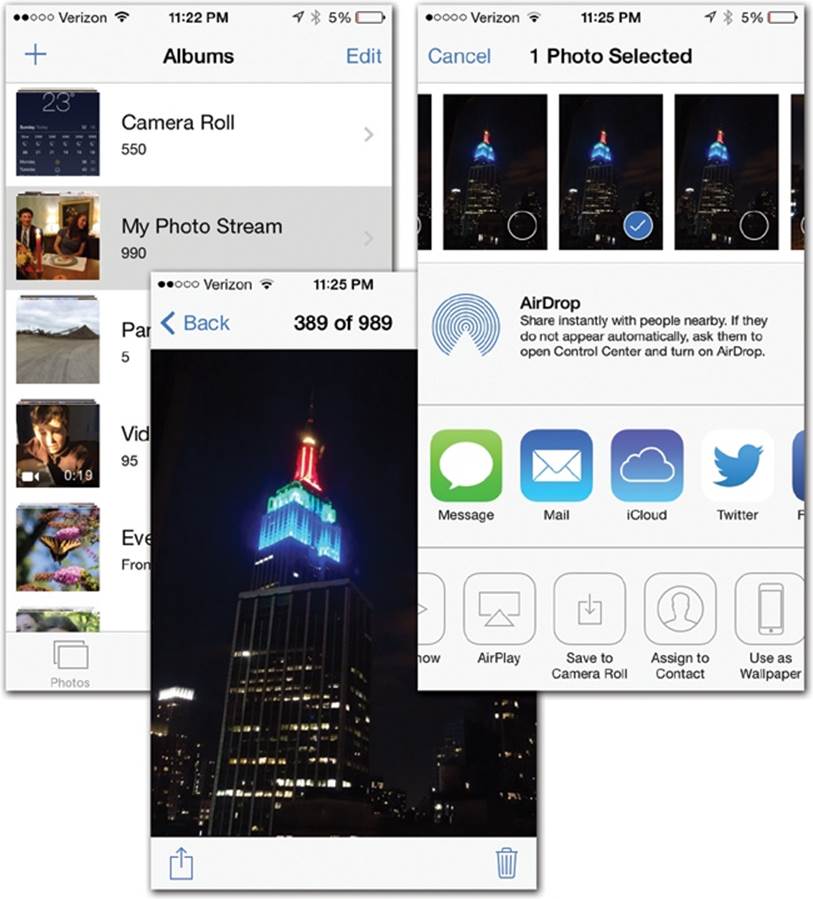

§ iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch. Open your Photos app. There it is: a listing called My Photo Stream. It shows the most recent 1,000 photos you’ve taken with any of your other i-gadgets, or that you’ve imported to your computer from a scanner or a digital camera.

Now, Apple realizes that your i-gadget doesn’t have nearly as much storage available as your Mac; you can’t yet buy an iPad with 750 gigabytes of storage. That’s why, on your iPhone/iPad/iPod, your Photo Stream consists of just the last 1,000 photos. (There’s another limitation, too: The iCloud servers store your photos for 30 days. As long as your gadgets go online at least once a month, they’ll remain current with the Photo Stream.)

Once a photo arrives, you can save it to your Camera Roll, where it’s permanently saved. See Figure 10-12.

NOTE

Photo Stream is the one iCloud feature that doesn’t sync over the cellular airwaves. It sends photos around only when you’re in a WiFi hotspot or connected to a wired network.

Figure 10-12. Left: Why, look! It’s photos you imported onto your Mac at home. How’d they get here on the iPhone? iCloud! Middle: To rescue one of these photos from the 1,000-photo rule, open it. Then tap the ![]() button. Right: Finally, tap Save to Camera Roll (bottom row, center). Now, even after that photo disappears from the Photo Stream, having been displaced by the 1,001st incoming photo, you’ll still have your permanent copy.

button. Right: Finally, tap Save to Camera Roll (bottom row, center). Now, even after that photo disappears from the Photo Stream, having been displaced by the 1,001st incoming photo, you’ll still have your permanent copy.

§ On the Mac. In iPhoto, your Photo Stream photos appear in a new album called, of course, Photo Stream. (On a Windows PC, you’d get a Photo Stream folder in your Pictures folder.)

You don’t have to worry about that 30-day, 1,000-photo business. Once pictures appear here, they’re here until you delete them.

This, in its way, is one of the best features in all of iCloudland, because it means you don’t have to sync your iPhone over a USB cable to get your photos onto your computer. It all happens automatically, wirelessly over WiFi.

§ Apple TV. When you’re viewing your photos on an Apple TV, a new album appears there called Photo Stream. There they are, ready for showing on the big plasma.

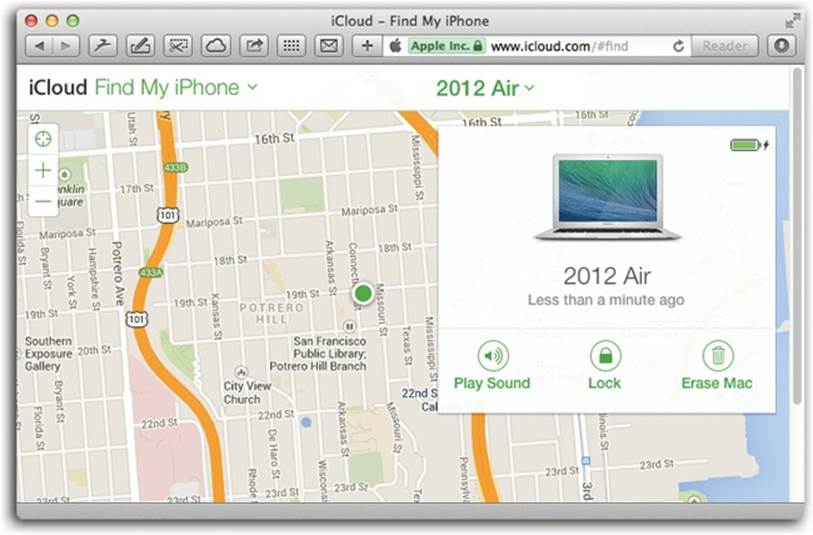

Find My Mac, Find My iPhone

Did you leave your iPhone somewhere? Did your laptop get stolen? Has that mischievous 5-year-old hidden your iPad again?

Now you can check into iCloud.com to see exactly where your Mac, iPhone, or iPad is. You can even make it beep loudly for 2 minutes, so you can figure out which couch cushion it’s under, or which jacket pocket you left it in. If the missing item is an iPad or an iPhone, you can make it beep even if the ringer switch is off, and even if the phone is asleep. You can also make a message pop up on the screen; if you actually left the thing in a taxi or on some restaurant table, you can use this feature to plead for its return. The bottom line: If you ever lose your Apple gear, you have a fighting chance at getting it back.

(That’s if it’s online, and if you turned on Find My Mac in the iCloud panel of System Preferences.)

If an ethical person finds your phone, you might get it back. If it’s a greedy person who says, “Hey, cool! A free iPhone!” then maybe you can bombard him with so many of these messages that he gives it back in exasperation.

If not, you can either lock the gadget with a password (yes, by remote control) or even avail yourself of one more amazing last-ditch feature: Remote Wipe.

That means erasing your data by remote control, from wherever you happen to be. The evil thief can do nothing but stare in amazement as the phone, tablet, or Mac suddenly erases itself, winding up completely empty.

NOTE

And by the way: The evil thief can’t erase your stolen phone or tablet himself, thanks to Apple’s ingenious Activation Lock feature. It prevents the phone or tablet from being erased without your Apple ID and password. Good luck with that, bad guy!

If you ever get the phone back, you can just sync it with iTunes, and presto! Your stuff is back on the phone—at least everything from your last sync.

To set up your Mac so you can find it remotely, open System Preferences→iCloud. Make sure Find My Mac is turned on. That’s all there is to it.

Later, if the worst should come to pass and you can’t find your Mac, go to any computer and call up www.icloud.com. Log in with your Apple name and password.

Click the ![]() icon at upper left; in the list of iCloud features, click Find My iPhone. If you’re asked for your password again, type it; Apple wants to make sure it’s really, really you who’s messing around with your account settings.

icon at upper left; in the list of iCloud features, click Find My iPhone. If you’re asked for your password again, type it; Apple wants to make sure it’s really, really you who’s messing around with your account settings.

Immediately, the Web site updates to show you, on a map, the current location of your Macs (and iPhones, iPod Touches, and iPads); see Figure 10-13.

NOTE

If they’re not online, or if they’re turned all the way off, you won’t see their current locations. If they’re just asleep—even if your laptop’s lid is closed—you will.

Figure 10-13. The location process can take a couple of minutes. You can zoom into or out of the map, click Satellite to see an overhead photo of the area, or click Hybrid to see the photo with street names superimposed. The big green dot indicates that one of your Apple gadgets isn’t as lost as you thought.

If just knowing where the thing is isn’t enough to satisfy you, then click the little pushpin that represents your phone (or choose its name from the menu at top center), and try one of these three buttons:

§ Play Sound. When you click this button, a very loud sonar-like pinging sound instantly chimes on your Mac, wherever it is, no matter what its volume setting. Even if your laptop is closed and asleep, it will ring. The idea is to help you find it in whatever room of the house you left it in.

When it’s all over, Apple sends an email confirmation to your @me.com address.

§ Lock. What if you worry about the security of your Mac’s info, but you don’t want to erase it completely and just want to throw a low-level veil of casual protection over the thing? Easy: Lock it by remote control.

The Lock button lets you make up a four-digit passcode (which overrides the one you already had, if any). Without it, the sleazy crook can’t get into your Mac without erasing it.

You’re also offered the opportunity to type a message; it will appear on the Unlock screen, below the four boxes where you’re supposed to type in the four-digit code. You might type something like, “Thank you for finding my lost laptop! Please call me at 212-556-1000 for a delicious frosty reward.”

§ Erase. This is the last-ditch security option, for when your immediate concern isn’t so much the Mac as all the private stuff that’s on it. Click this button, confirm the dire warning box, and click Erase All Data. By remote control, you’ve just erased everything from your Mac, wherever it may be. (If it’s ever returned, you can restore it from your Time Machine backup.)

Once you’ve wiped the Mac, you can no longer find it or send messages to it using Find My Mac.

Apple offers an email address as part of each iCloud account. Of course, you already have an email account. So why bother? The first advantage is the simple address: YourName@me.com. (It may look like what you’ve got is YourName@icloud.com, but mail sent to YourName@me.comcomes to exactly the same place. These addresses are aliases of each other.)

Second, me.com addresses are integrated into OS X’s Mail program, as you’ll see in the next chapter. And, finally, you can read your me.com email from any computer anywhere in the world, via the iCloud.com Web site, or on your iPhone/iPod Touch/iPad.

UP TO SPEED: ITUNES MATCH

Anything you’ve ever bought from the iTunes music store is now available for playing on any Apple gadget you own. We get it.

A lot of people, however, have music in their collections that didn’t come from the iTunes store. Maybe they ripped some audio CDs into their computers. Maybe they acquired some music from, ahem, a friend.

What a sad situation! You’ve got some of your music available with you on any computer or mobile gadget, and some that’s stranded at home on your computer.

Enter iTunes Match. It’s an Apple service that lets you store your entire collection, including songs that didn’t come from Apple, online, for $25 a year.

The iTunes software analyzes the songs in your collection. If it finds a song that’s also available in iTunes, then—bing!—that song becomes available for your playback pleasure, without your actually having to transfer your copy to Apple. Apple says, in effect: “Well, our copy of the song is just as good as yours, so you’re welcome to listen to our copy on any of your machines.”

Truth is, in fact, Apple’s copy is probably better than your copy. You get to play back the song at iTunes’ 256-Kbps quality, no matter how grungy your own copy was.

If there’s a song or two in your collection that are not among Apple’s 20 million tracks, you can upload them to Apple.

The advantages of forking over the $25 a year are (a) you can listen to all your music from any computer/phone/tablet, (b) using the song-matching system saves you hours or days of uploading time, and (c) that audio-quality upgrade. And, oh yeah: (d) You can listen to iTunes Radio (TV, movies, and movie rentals), without any ads.

The disadvantage: You’re paying $25 a year.

To make things even sweeter, your me.com mail is completely synced. Delete a message on one gadget, and you’ll find it in the Deleted Mail folder on another. Send a message from your iPad, and you’ll find it in the Sent Mail folder on your Mac. And so on.

Books, Music, Apps, Movies: The Locker in the Sky

Apple, as if you hadn’t noticed, has become a big seller of multimedia files. It has the biggest music store in the world. It has the biggest app store, for both i-gadgets and Macs. It sells an awful lot of TV shows and movies. Its ebook store, iBooks, is no Amazon.com, but it’s chugging along.

When you buy a song, movie, app, or book, you’ve always been allowed to copy it to all your other Apple equipment—no extra charge. But iCloud automates, or at least formalizes, that process. Once you buy something, it’s added to a tidy list of items that you can download to all your othermachines.

Here’s how to grab them:

§ iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch. Open the App Store icon (for apps), the iBooks program (for books), or the iTunes Store app (for songs or TV shows; tap the category you want). Tap More. Tap Purchased. Tap Not on This iPhone.

There they are: all the items you’ve bought on your other machines using the same Apple ID. To download anything listed here onto this machine, tap the cloud-with-arrow button. Or tap an album name to see the list of songs on it so you can download just some of those songs.

You can save yourself all that tapping by opening Settings→iTunes & App Store and turning the Automatic Downloads switches to On (for Music, Apps, and Books). From now on, whenever you’re in WiFi, stuff you’ve bought on other Apple machines gets downloaded to this oneautomatically, in the background.

§ Mac. Open the App Store program (for apps) or the iTunes app (for songs, TV shows, books, and movies). Under the Purchased heading, there they are: all the digital goodies you’ve bought using this Apple ID, ready to open or re-download if necessary.

TIP

To make this automatic, open iTunes. Choose iTunes→Preferences→Store. Under Automatic Downloads, turn on Music, Apps, and Books, as you see fit. Click OK.