Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition (2014)

Part I. Welcome to Macintosh

Chapter 1. How the Mac Is Different

When you get right down to it, the job description of every operating system is pretty much the same. Whether it’s Mac OS X, Windows 8, or Billy Bob’s System-Software Special, any OS must serve as the ambassador between the computer and you, its human operator. It must somehow represent your files and programs on the screen so you can open them; offer some method of organizing your files; present onscreen controls that affect your speaker volume, mouse speed, and so on; and communicate with your external gadgets, like disks, printers, and digital cameras.

In other words, OS X offers roughly the same features as Windows. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that these features are called different things and parked in different spots. As you could have predicted, this rearrangement of features can mean a good deal of confusion for you, the Macintosh foreigner. For the first few days or weeks, you may instinctively reach for certain familiar features that simply aren’t where you expect to find them, the way your tongue keeps sticking itself into the socket of a newly extracted tooth.

To minimize your frustration, therefore, read this chapter first. It makes plain the most important and dramatic differences between the Windows method and the Macintosh way.

Power On, Dude

As a critic might say, Apple is always consistent with its placement of the power button: It’s different on every model.

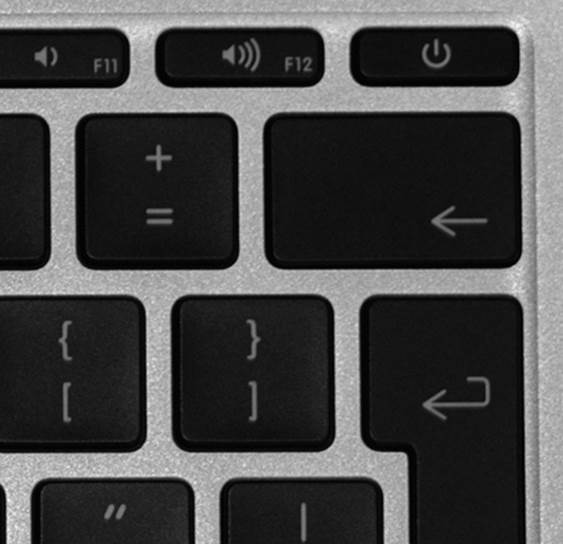

On iMacs and Mac Minis, the power button is on the back panel. On the Mac Pro, it’s on the front panel. And on laptop Macs, the button is either a key in the upper-right corner of the keyboard or a round button near the upper-right of the keyboard. (Then again, if you have a laptop, you should get into the habit of just closing the lid when you’re done working and opening it to resume; the power button rarely plays a role in your life.)

In every case, though, the power button looks the same (Figure 1-1): It bears the ![]() logo.

logo.

Figure 1-1. Every Mac’s power button looks like this, although it might be hard to find. The good news: Once you find it, it’ll pretty much stay in the same place.

Right-Clicking and Shortcut Menus

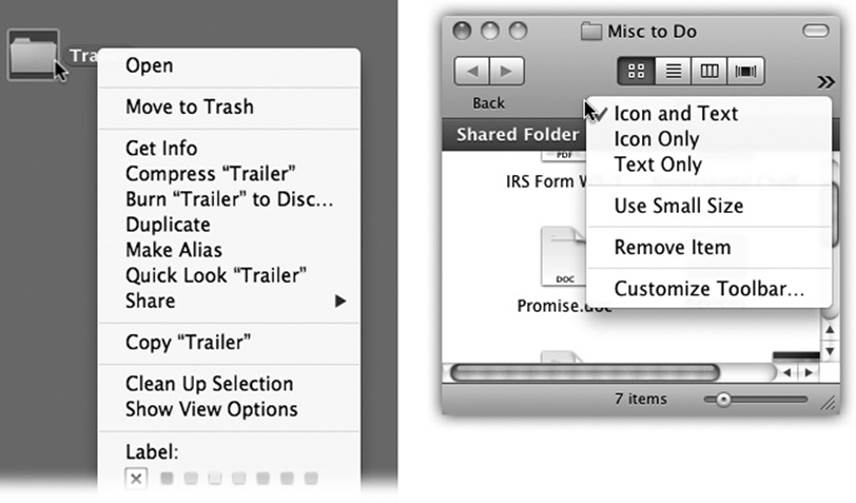

You can get terrific mileage out of shortcut menus on the Mac, just as in Windows (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2. A shortcut menu is one that pops out of something you’re clicking—an icon, a button, a folder. The beauty of shortcut menus is that they’re contextual. They bring up commands in exactly the spots where they’re most useful, in menus that are relevant only to what you’re clicking.

They’re so important, in fact, that it’s worth these paragraphs to explain the different ways you can trigger a “right-click.” (Apple calls it a secondary click, because not all of these methods actually involve a second mouse button. Also, left-handed people may want to make the left mouse button trigger a right-click.)

§ Use the trackpad. If you have a trackpad (a laptop, for example), you can trigger a right-click in all kinds of ways.

Out of the box, you do it by clicking the trackpad with two fingers. The shortcut menu pops right up.

Or you can point to whatever you want to click. Rest two fingers on the trackpad—and then click with your thumb.

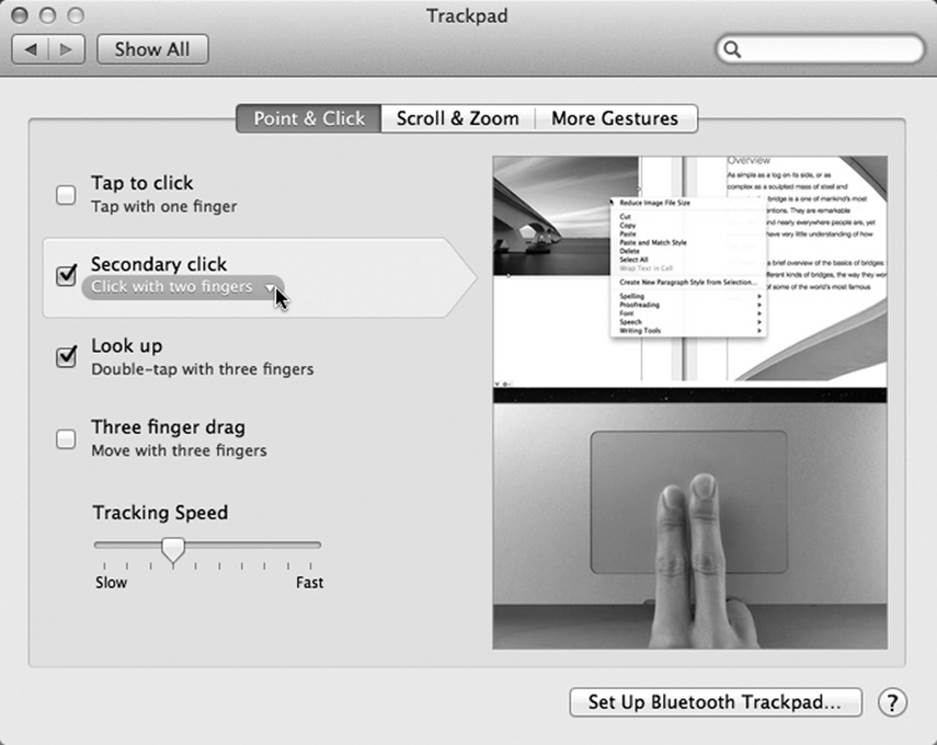

But even those aren’t the end of your options. In System Preferences→Trackpad, you can turn on even more right-click methods (and even watch little videos on how to do them; see Figure 1-3). For example, you can “right-click” by clicking either the lower-right or lower-left corner of the trackpad—one finger only.

Figure 1-3. The Trackpad pane of System Preferences looks different depending on your laptop model. But this one shows the three ways to get a “right-click.”

§ Control-click. You can open the shortcut menu of something on the Mac screen by Control-clicking it. That is, while pressing the Control key (bottom row), click the mouse on your target.

§ Right-click. Experienced computer fans have always preferred the one-handed method: right-clicking. That is, clicking something by pressing the right mouse button on a two-button mouse.

“Ah, but that’s what’s always driven me nuts about Apple,” goes the common refrain,“their refusal to get rid of their stupid one-button mouse!”

Well, not so fast.

First of all, you can attach any old $6 USB two-button mouse to the Mac, and it’ll work flawlessly. Recycle the one from your old PC, if you like.

Furthermore, if you have a desktop Mac, then you already have a two-button mouse—but you might not realize it. Take a look: Is it a white, shiny plastic capsule with a tiny, gray scrolling track-pea on the far end? Then you have a Mighty Mouse. Is it a cordless, flattened capsule instead? Then it’s the newer Magic Mouse. Each has a secret right mouse button. It doesn’t work until you ask for it.

To do that, choose ![]() →System Preferences. Click Mouse. There, in all its splendor, is a diagram of the Mighty or Magic Mouse.

→System Preferences. Click Mouse. There, in all its splendor, is a diagram of the Mighty or Magic Mouse.

Your job is to choose Secondary Button from the pop-up menu that identifies the right side of the mouse.

From now on, even though there aren’t two visible mouse buttons, your mouse does, in fact, register a left-click or a right-click depending on which side of the mouse you push down. It works a lot more easily than it sounds like it would.

Logging Out, Shutting Down

If you’re the only person who uses your Mac, finishing up a work session is simple. You can either turn off the machine or simply let it go to sleep, in any of several ways.

Sleep Mode

If you’re still shutting down your Mac after each use, you may be doing a lot more waiting than necessary. Sleep mode consumes very little power, keeps everything you were doing open and available, and wakes up almost immediately when you press a key or click the mouse.

To make your machine sleep, do one of the following:

§ Close the lid. (Hint: This tip works primarily on laptops.)

§ Press the power button (![]() ). In Mavericks, tapping that button makes both laptops and desktops drop off to sleep instantly.

). In Mavericks, tapping that button makes both laptops and desktops drop off to sleep instantly.

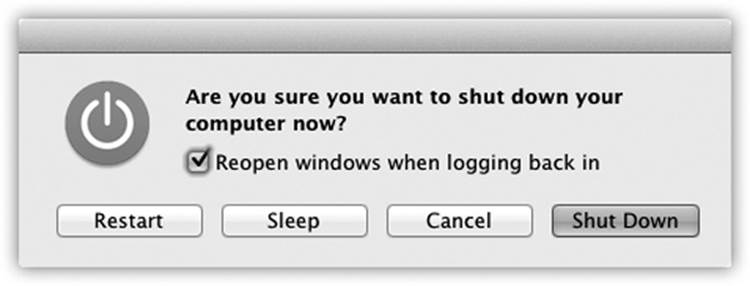

§ Hold down the power button (![]() ) for 2 seconds. You get the box shown in Figure 1-4; hit Sleep (or type S).

) for 2 seconds. You get the box shown in Figure 1-4; hit Sleep (or type S).

§ Choose ![]() →Sleep. Or press Option-⌘-

→Sleep. Or press Option-⌘-![]() .

.

§ Press Control-![]() . In the dialog box shown in Figure 1-4, click Sleep (or type S).

. In the dialog box shown in Figure 1-4, click Sleep (or type S).

§ Just walk away, confident that the Energy Saver setting in System Preferences will send the machine off to dreamland automatically at the specified time.

TIP

Ordinarily, closing your MacBook’s lid means putting it to sleep. And, ordinarily, putting it to sleep means cutting it off from the world. But OS X’s Power Nap feature lets your Mac stay connected to your network and to the Internet, even while it’s otherwise sleeping. It can download email, back up your stuff, download software updates, and so on.

Figure 1-4. Once the Shut Down dialog box appears, you can press the S key instead of clicking Sleep, R for Restart, Esc for Cancel, or Return for Shut Down.

Restart

You shouldn’t have to restart the Mac very often—only in times of severe troubleshooting mystification, in fact. Here are a few ways to do it:

§ Choose ![]() →Restart. A confirmation dialog box appears; click Restart (or press Return).

→Restart. A confirmation dialog box appears; click Restart (or press Return).

TIP

If you press Option as you release the mouse on the ![]() →Restart command, you won’t be bothered by an “Are you sure?” confirmation box.

→Restart command, you won’t be bothered by an “Are you sure?” confirmation box.

§ Press Control-⌘-![]() .

.

§ Press Control-![]() (or hold down the

(or hold down the ![]() button) to summon the dialog box shown in Figure 1-4; click Restart (or type R).

button) to summon the dialog box shown in Figure 1-4; click Restart (or type R).

Shut Down

To shut down your machine completely (when you don’t plan to use it for more than a couple of days, when you plan to transport it, and so on), do one of the following:

§ Choose ![]() →Shut Down. A simple confirmation dialog box appears; click Shut Down (or press Return).

→Shut Down. A simple confirmation dialog box appears; click Shut Down (or press Return).

TIP

Once again, if you press Option as you release the mouse, no confirmation box appears.

§ Press Control-Option-⌘-![]() . (It’s not as complex as it looks—the first three keys are all in a tidy row to the left of the space bar.)

. (It’s not as complex as it looks—the first three keys are all in a tidy row to the left of the space bar.)

§ Press Control-![]() (or hold down the

(or hold down the ![]() button) to summon the dialog box shown in Figure 1-4. Click Shut Down (or press Return).

button) to summon the dialog box shown in Figure 1-4. Click Shut Down (or press Return).

§ Wait. If you’ve set up the Energy Saver preferences to shut down the Mac automatically at a specified time, then you don’t have to do anything.

The “Reopen windows” Option

In the Shut Down dialog box illustrated in Figure 1-4, you’ll notice a checkbox called “Reopen windows when logging back in.” That option does something very useful: The next time you start up your Mac, every running program, and every open window, will reopen exactly as it was at the moment you used the Restart or Shut Down command. The option gives the Mac something like the old Hibernate feature in Windows—and saves you a lot of reopening the next time you sit down to work.

If you turn off that checkbox when you click Restart or Shut Down, then your next startup will take you to the desktop, with no programs running. And if you want the Mac to stop asking—if you never want your programs and windows to reopen—then open ![]() →System Preferences→General, and turn on “Close windows when quitting an application.”

→System Preferences→General, and turn on “Close windows when quitting an application.”

Log Out

If you share your Mac, then you should log out when you’re done. Doing so ensures that your stuff is safe from the evil and the clueless even when you’re out of the room. To do it, choose ![]() →Log Out Casey (or whatever your name is). Or, if you’re in a hurry, press Shift-⌘-Q.

→Log Out Casey (or whatever your name is). Or, if you’re in a hurry, press Shift-⌘-Q.

When the confirmation dialog box appears, click Log Out (or press Return) or just wait for 1 minute (a message performs the countdown for you). The Mac hides your world from view and displays the Log In dialog box, ready for its next victim.

TIP

Last time: If you press Option as you release the mouse on the ![]() →Log Out command, you squelch the “Are you sure?” box.

→Log Out command, you squelch the “Are you sure?” box.

The Menu Bar

On the Mac, there’s only one menu bar. It’s always at the top of the screen. The names of these menus, and the commands inside them, change to suit the window you’re currently using. That’s different from Windows, where a separate menu bar appears at the top of every window.

Mac and Windows devotees can argue the relative merits of these two approaches until they’re blue in the face. All that matters, though, is that you know where to look when you want to reach for a menu command. On the Mac, you always look upward.

Finder = Windows Explorer

In OS X, the “home base” program—the one that appears when you first turn on the machine and shows you the icons of all your folders and files—is called the Finder. This is where you manage your folders and files, throw things away, manipulate disks, and so on. (You may also hear it called the desktop, since the items you find there mirror the files and folders you might find on a real-life desktop.)

Getting used to the term “Finder” is worthwhile, though, because it comes up so often. For example, the first icon on your Dock is labeled “Finder,” and clicking it always takes you back to your desktop.

Dock = Taskbar

At the bottom of almost every OS X screen sits a tiny row of photorealistic icons. This is the Dock, a close parallel to the Windows taskbar. (As in Windows, it may be hidden or placed on the left or the right edge of the screen instead—options that appeal primarily to power users and eccentrics.)

The Dock displays the icons of all your open windows and programs, which are denoted by small, glowing markers beneath their icons. Clicking these icons opens the corresponding files, folders, disks, documents, and programs. If you click and hold (or right-click) an open program’s icon, you’ll see a pop-up list of the open windows in that program, along with Quit and a few other commands.

When you close a program, its icon disappears from the Dock (unless you’ve secured it there for easy access, as described on Secret Menus).

TIP

You can cycle through the various open programs on your Mac by holding down the ⌘ key and pressing Tab repeatedly. (Sound familiar? It’s just like Alt-Tabbing in Windows.) And if you just tap ⌘-Tab, you bounce back and forth between the two programs you’ve used most recently.

What you may find confusing at first, though, is that the Dock also performs one function of the old Windows Start menu: It provides a “short list” of programs and files that you use often, for easy access. To add a new icon to the Dock, just drag it there (put programs to the left of the divider line; everything else goes on the right). To remove an icon from the Dock, just drag it away. As long as that item isn’t actually open at the moment, it disappears from the Dock with a little animated puff of smoke when you release the mouse button.

The bottom line: On the Mac, a single interface element—the Dock—exhibits characteristics of both the Start menu (it lists frequently used programs) and the taskbar (it lists currently open programs and files). (The Windows 7 taskbar does the same thing.)

If you’re still confused, Chapter 2 should help clear things up.

Menulets = Tray

Most Windows fans refer to the row of tiny status icons at the lower-right corner of the screen as the tray, even though Microsoft’s official term is the notification area. (Why use one syllable when eight will do?)

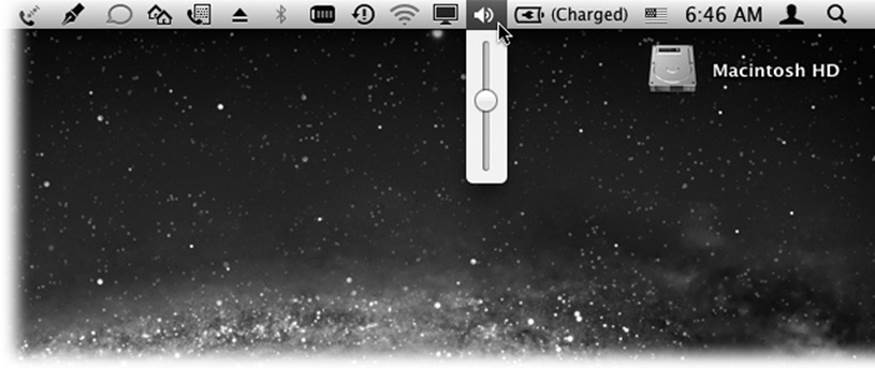

Macintosh fans wage a similar battle of terminology when it comes to the little menu-bar icons shown in Figure 1-5. Apple calls them Menu Extras, but Mac fans prefer to call them menulets.

In any case, these menu-bar icons are cousins of the Windows tray—each is both an indicator and a menu that provides direct access to certain settings. One menulet lets you adjust your Mac’s speaker volume, another lets you change the screen resolution, another shows you the remaining power in your laptop battery, and so on.

Figure 1-5. These little guys are the cousins of the controls found in the Windows system tray.

Making a menulet appear usually involves turning on a certain checkbox. These checkboxes lurk on the various panes of System Preferences (Chapter 16), which is the Mac equivalent of the Control Panel. (To open System Preferences, choose its name from the ![]() menu or click the gears icon on the Dock.)

menu or click the gears icon on the Dock.)

Here’s a rundown of the most useful Apple menulets, complete with instructions on where to find the magic on/off checkbox for each.

§ AirPlay lets you send the Mac’s screen image to a TV, provided that you have an Apple TV (details on AirPlay). This menulet turns blue when you’re projecting, and its menu lets you turn AirPlay on or off. To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Displays→Display tab.

§ AirPort lets you turn your WiFi (wireless networking) circuitry on or off, join existing wireless networks, and create your own private ones. To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Network. Click Wi-Fi.

TIP

You can Option-click this menulet to produce a secret menu full of details about the wireless network you’re on right now. You see its channel number, password-security method (WEP, WPA, None, whatever), speed, and such geeky details as the MCS Index and RSSI.

§ Battery shows how much power remains in your laptop’s battery, how much time is left to charge it, whether it’s plugged in, and more. When you click the icon to open the menu, you see how many actual hours and minutes are left on the charge. You can also choose Show Percentage to add a percentage-remaining readout (43%) to the menu bar.

This Battery menu also shows something that can be even more useful: a list of the most power-hungry open programs (“Apps Using Significant Energy”). That’s handy when you’re trying to eke out every last drop of battery life for your laptop. To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Energy Saver.

TIP

If you Option-click the Battery menulet, you get to see the status of your battery’s health. A Condition command appears. It might say, for example, “Condition: Normal,” “Service Battery,” “Replace Soon,” or “Replace Now.” Of course, we all know laptop batteries don’t last forever; they begin to hold less of a charge as they approach 500 or 1,000 recharges, depending on the model.

Is Apple looking out for you, or just trying to goose the sale of replacement batteries? You decide.

§ Bluetooth connects to Bluetooth devices, “pairs” your Mac with a cellphone, lets you send or receive files wirelessly (without the hassle of setting up a wireless network), and so on. To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Bluetooth.

TIP

You can Option-click this menulet to see three additional lines of nerdy details about your Bluetooth setup: the Bluetooth software version you’re using, the name of your Mac (which is helpful when you’re trying to make it show up on another Bluetooth gadget), and its Bluetooth MAC [hardware] address.

§ Clock is the menu-bar clock that’s been sitting at the upper-right corner of your screen from Day One. Click it to open a menu where you can check today’s date, convert the menu-bar display to a tiny analog clock, and so on. To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Date & Time. On the Clock tab, turn on “Show date and time in menu bar.”

§ Time Machine lets you start and stop Time Machine backups (see Chapter 5). To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Time Machine.

§ User identifies the account holder (Chapter 14) who’s logged in at the moment. To make this menulet appear (in bold, at the far-right end of the menu bar), turn on fast user switching, which is described on Fast User Switching.

§ Volume, of course, adjusts your Mac’s speaker or headphone volume. To find the Show checkbox: Open System Preferences→Sound.

To remove a menulet, ⌘-drag it off your menu bar, or turn off the corresponding checkbox in System Preferences. You can also rearrange menulets by ⌘-dragging them horizontally.

These little guys are useful, good-looking, and respectful of your screen space. The world could use more inventions like menulets.

Keyboard Differences

Mac and PC keyboards are subtly different. Making the switch involves two big adjustments: figuring out where the special Windows keys went (like Alt and Ctrl)—and figuring out what to do with the special Macintosh keys (like ⌘ and Option).

Where the Windows Keys Went

Here’s how to find the Macintosh equivalents of familiar PC keyboard keys:

§ Ctrl key. The Macintosh offers a key labeled Control (or, on laptops, “ctrl”), but it isn’t the equivalent of the PC’s Ctrl key. The Mac’s Control key is primarily for helping you “right-click” things, as described earlier.

Instead, the Macintosh equivalent of the Windows Ctrl key is the ⌘ key. It’s right next to the space bar. It’s pronounced “command,” although novices can often be heard calling it the “pretzel key,” “Apple key,” or “clover key.”

Most Windows Ctrl-key combos correspond perfectly to ⌘-key sequences on the Mac. The Save command is now ⌘-S instead of Ctrl+S, Open is ⌘-O instead of Ctrl+O, and so on.

NOTE

Mac keyboard shortcuts are listed at the right side of each open menu, just as in Windows. Unfortunately, they’re represented in the menu with goofy symbols instead of their true key names. Here’s your cheat sheet to the menu keyboard symbols: ![]() represents the Shift key,

represents the Shift key, ![]() means the Option key, and

means the Option key, and ![]() refers to the Control key.

refers to the Control key.

§ Alt key. On North American Mac keyboards, a key on the bottom row is labeled both Alt and Option. This is the closest thing the Mac offers to the Windows Alt key.

In many situations, keyboard shortcuts that involve the Alt key in Windows use the Option key on the Mac. For example, in Microsoft Word, the keyboard shortcut for the Split Document Window command is Alt+Ctrl+S in Windows, but Option-⌘-T on the Macintosh.

Still, these two keys aren’t exactly the same. Whereas the Alt key’s most popular function is to control the menus in Windows programs, the Option key on the Mac is a “miscellaneous” key that triggers secret functions and special characters.

For example, when you hold down the Option key as you click the Close or Minimize button on a Macintosh window, you close or minimize all open desktop windows. And if you press the Option key while you type R, G, or 2, you get the ®, ©, and ™ symbols in your document, respectively. (See Input Sources to find out how you can see which letters turn into which symbols when pressed with Option.)

§ ![]() key. As you probably could have guessed, there is no Windows-logo key on the Macintosh. Then again, there’s no Start menu to open by pressing it, either.

key. As you probably could have guessed, there is no Windows-logo key on the Macintosh. Then again, there’s no Start menu to open by pressing it, either.

TIP

Just about any USB keyboard works on the Mac, even if the keyboard was originally designed to work with a PC. Depending on the manufacturer of the keyboard, the Windows-logo key may work just like the Mac’s ⌘ key.

§ Backspace and Delete. On the Mac, the backspace key is labeled Delete, although it’s in exactly the same place as the Windows Backspace key.

The Delete key in Windows (technically, the forward delete key, because it deletes the character to the right of the insertion point) is a different story. On a desktop Macintosh with a full-size keyboard, it’s labeled with Del and the ![]() symbol.

symbol.

On small Mac keyboards (like laptop and wireless keyboards), this key is missing. You can still perform a forward delete, however, by pressing the regular Delete key while pressing the Fn key in the corner of the keyboard.

§ Enter. Most full-size Windows keyboards have two Enter keys: one at the right side of the alphabet keyboard and one in the lower-right corner of the number pad. They’re identical in function; pressing either one serves to “click” the OK button in a dialog box, for example.

On the Mac, the big key on the number pad still says Enter, but the key on the alphabet keyboard is labeled Return. Most of the time, their function is identical—either can “click” the OK button of a dialog box. Every now and then, though, you’ll run across a Mac program where Return and Enter do different things. In Microsoft Word for OS X, for example, Shift-Return inserts a line break, but Shift-Enter creates a page break.

What the Special Mac Keys Do

So much for finding the Windows keys you’re used to. There’s another category of keys worth discussing: those on the Mac keyboard you’ve never seen before.

To make any attempt at an explanation even more complicated, Apple’s keyboards keep changing. The one you’re using right now is probably one of these models:

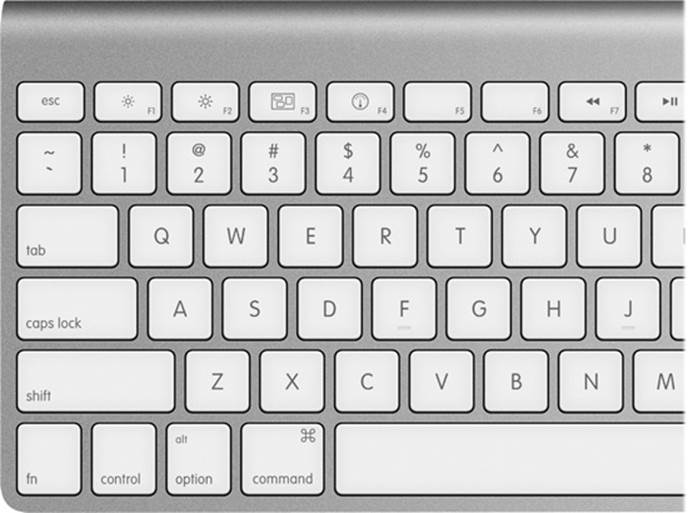

§ The current keyboards, where the keys are flat little jobbers that poke up through square holes in the aluminum (Figure 1-6). That’s what you get on current laptops, wired keyboards, and Bluetooth wireless keyboards.

§ The older, plastic desktop keyboards, or the white or black plastic laptop ones.

Here, then, is a guided tour of the non-typewriter keys on the modern Mac keyboard:

§ Fn. How are you supposed to pronounce “Fn”? Not “function,” certainly; after all, the F-keys on the top row are already known as function keys. And not “fun”; goodness knows, the Fn key isn’t particularly hilarious to press.

What it does, though, is quite clear: It changes the purpose of certain keys. That’s a big deal on laptops, which don’t have nearly as many keys as desktop keyboards. So for some of the less commonly used functions, you’re supposed to press Fn and a regular key. (For example, Fn turns the ![]() key into a Page Up key, which scrolls upward by one screenful.)

key into a Page Up key, which scrolls upward by one screenful.)

NOTE

On most Mac keyboards, the Fn key is in the lower-left corner. The exception is the full-size Apple desktop keyboard (the one with a numeric keypad); there, the Fn key is in the little block of keys between the letter keys and the number pad.

You’ll find many more Fn examples in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1-6. On the top row of aluminum Mac keyboards, the F-keys have dual functions. Ordinarily, the F1 through F4 keys correspond to Screen Dimmer, Screen Brighter, Exposé, and Dashboard. Pressing the Fn key in the corner changes their personalities, though.

§ Numeric keypad. The number-pad keys do exactly the same thing as the numbers at the top of the keyboard. But with practice, typing things like phone numbers and prices is much faster with the number pad, since you don’t have to look down at what you’re doing.

Apple has been quietly eliminating the numeric keypad from most of its keyboards, but you can still find it on some models.

§ ![]() ,

, ![]() (F1, F2). These keys control the brightness of your screen. Usually, you can tone it down a bit when you’re in a dark room or when you want to save laptop battery power; you’ll want to crank it up in the sun.

(F1, F2). These keys control the brightness of your screen. Usually, you can tone it down a bit when you’re in a dark room or when you want to save laptop battery power; you’ll want to crank it up in the sun.

§ ![]() (F3). This one fires up Mission Control, the handy window-management feature described in Chapter 4.

(F3). This one fires up Mission Control, the handy window-management feature described in Chapter 4.

§ ![]() or

or ![]() (F4). Tap the

(F4). Tap the ![]() key to open Dashboard, the archipelago of tiny, single-purpose widgets like Weather, Stocks, and Movies. Chapter 4 describes Dashboard in detail.

key to open Dashboard, the archipelago of tiny, single-purpose widgets like Weather, Stocks, and Movies. Chapter 4 describes Dashboard in detail.

On recent Macs, the F4 key bears a ![]() logo instead. Tapping it opens Launchpad, which is described on Launchpad.

logo instead. Tapping it opens Launchpad, which is described on Launchpad.

§ ![]() ,

, ![]() (F5, F6). Most recent Mac laptops have light-up keys, which is very handy indeed when you’re typing in the dark. The key lights are supposed to come on automatically when it’s dark, but you can also control the illumination yourself by tapping these keys. (On most other Macs, the F5 and F6 keys aren’t assigned to anything. They’re free for you to use as you see fit.)

(F5, F6). Most recent Mac laptops have light-up keys, which is very handy indeed when you’re typing in the dark. The key lights are supposed to come on automatically when it’s dark, but you can also control the illumination yourself by tapping these keys. (On most other Macs, the F5 and F6 keys aren’t assigned to anything. They’re free for you to use as you see fit.)

§ ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() (F7, F8, F9). These keys work in the programs you’d expect: iTunes, QuickTime Player, DVD Player, and other programs where it’s handy to have Rewind, Play/Pause, and Fast Forward buttons.

(F7, F8, F9). These keys work in the programs you’d expect: iTunes, QuickTime Player, DVD Player, and other programs where it’s handy to have Rewind, Play/Pause, and Fast Forward buttons.

TIP

Tap either ![]() or

or ![]() to skip to the previous or next track or chapter. Hold one down to rewind or fast-forward.

to skip to the previous or next track or chapter. Hold one down to rewind or fast-forward.

§ ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() (F10, F11, F12). These three keys control your speaker volume. The

(F10, F11, F12). These three keys control your speaker volume. The ![]() key means Mute; tap it once to cut off the sound completely and again to restore its previous level. Tap the

key means Mute; tap it once to cut off the sound completely and again to restore its previous level. Tap the ![]() repeatedly to make the sound level lower, the

repeatedly to make the sound level lower, the ![]() key to make it louder.

key to make it louder.

With each tap, you see a big white version of each key’s symbol on your screen, your Mac’s little nod to let you know it understands your efforts.

TIP

If you hold down the Shift and Option keys, then tapping the volume keys adjusts the volume by smaller increments, just as with the brightness keys.

§ ![]() . This is the Eject key. When there’s a CD or DVD in your Mac, tap this key to make the computer spit it out.

. This is the Eject key. When there’s a CD or DVD in your Mac, tap this key to make the computer spit it out.

If your Mac doesn’t have a DVD drive (modern ones don’t), it doesn’t have this key, either.

§ Home, End. The Home key jumps to the top of a window, the End key to the bottom. If you’re looking at a list of files, then the Home and End keys jump to the top or bottom of the list. In iPhoto, they jump to the first or last photo in your collection. In iMovie, the Home key rewinds your movie to the very beginning. In Safari, they send you to the top or bottom of the Web page.

(In Word, they jump to the beginning or end of the line. But then again, Microsoft has always had its own ways of doing things.)

On keyboards without a dedicated block of number keys, you get these functions by holding down Fn as you tap the ![]() and

and ![]() keys.

keys.

§ Pg Up, Pg Down. These keys scroll up or down by one screenful. The idea is to let you scroll through word-processing documents, Web pages, and lists without having to use the mouse.

On keyboards without a numeric keypad, you get these functions by pressing Fn plus the ![]() and

and ![]() keys.

keys.

§ Esc. Esc stands for Escape, and it means “cancel.” It’s fantastically useful. It closes dialog boxes, closes menus, and exits special modes like Quick Look, slideshows, screen savers, and so on. Get to know it.

§ Delete. The Backspace key.

§ ⌘. This key triggers keyboard shortcuts for menu items.

§ Control. The Control key triggers shortcut menus.

§ Option. The Option key (labeled Alt on keyboards in some countries) is sort of a “miscellaneous” key. It’s the equivalent of the Alt key in Windows.

It lets you access secret features—you’ll find them described all through this book—and type special symbols. For example, you press Option-4 to get the ¢ symbol, and Option-Y to get the ¥ (yen) symbol.

§ Help. In the Finder, Microsoft programs, and a few other places, this key opens up the electronic help screens. But you guessed that.

The Complicated Story of the Function Keys

As the previous section makes clear, the F-keys at the top of modern Mac keyboards come with predefined functions. They control screen brightness, keyboard brightness, speaker volume, music playback, and so on.

But they didn’t always. Before Apple gave F9, F10, and F11 to the fast-forward and speaker-volume functions, those keys controlled the Exposé window-management function described in Chapter 4.

So the question is: What if you don’t want to trigger the hardware features of these keys? What if you want pressing F1 to mean “F1” (which opens the Help window in some programs)? What if you want F9, F10, and F11 to control Exposé’s three modes?

For that purpose, you’re supposed to press the Fn key. The Fn key (lower left on small keyboards, center block of keys on the big ones) switches the function of the function keys. In other words, pressing Fn-F10 triggers an Exposé feature, even though the key has a Mute symbol (![]() ) painted on it.

) painted on it.

But here’s the thing: What if you use those F-keys for software features (like Cut, Copy, Paste, and Exposé) more often than the hardware features (like brightness and volume)?

In that case, you can reverse the logic, so that pressing the F-keys alone triggers software functions, and they govern brightness and audio only when you’re pressing Fn. To do that, choose ![]() →System Preferences→Keyboard. Turn on the cryptically worded checkbox “Use F1, F2, etc. as standard function keys.”

→System Preferences→Keyboard. Turn on the cryptically worded checkbox “Use F1, F2, etc. as standard function keys.”

And that’s it. From now on, you press the Fn key to get the functions painted on the keys (![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and so on).

, and so on).

Disk Differences

Working with disks is very different on the Mac. Whereas Windows is designed to show the names (letters) and icons for your disk drives, the Mac shows you the names and icons of your disks. You’ll never, ever see an icon for an empty drive, as you do in Windows.

As soon as you insert, say, a flash drive, you see its name and icon appear on the screen. In fact, every disk inside, or attached to, a Macintosh is represented on the desktop by an icon (see Figure 1-7). (Your main hard drive’s icon may or may not appear in the upper-right corner, depending on your settings in Finder→Preferences.)

Figure 1-7. You may see all kinds of disks on the OS X desktop (shown here: hard drive, CD, iPod, flash drive)—or none at all, if you’ve chosen to hide them using the Finder→Preferences command. But chances are pretty good you won’t be seeing many floppy disk icons. If you do decide to hide your disk icons, you can always get to them as you do in Windows: by opening the Computer window (Go→Computer).

If you prefer the Windows look, in which no disk icons appear on the desktop, it’s easy enough to recreate it on the Mac; choose Finder→Preferences and turn off the four checkboxes you see there (“Hard disks,” “External disks,” “CDs, DVDs, and iPods,” and “Connected servers.”)

Ejecting a disk from the Mac is a little bit different, too, whether it’s a CD, DVD, USB flash drive, shared network disk, iDisk, iPod, or external hard drive. You can go about it in any of these ways:

§ Hold down the ![]() key on your keyboard, if you have one (CDs and DVDs only).

key on your keyboard, if you have one (CDs and DVDs only).

§ Right-click the disk’s desktop icon. From the shortcut menu that appears, choose “Eject [whatever the disk’s name is].”

§ Click the disk’s icon and then choose File→“Eject [disk’s name]” (or press ⌘-E).

§ Drag the icon of the disk onto the Trash icon at the end of the Dock. (You’ll see its icon turn into a giant ![]() symbol, the Mac’s little acknowledgment that it knows what you’re trying to do.)

symbol, the Mac’s little acknowledgment that it knows what you’re trying to do.)

Where Your Stuff Is

If you open the icon for your main hard drive (Macintosh HD) from the Go→Computer window, for example, all you’ll find in the Macintosh HD window is a set of folders called Applications, Library, and Users.

Most of these folders aren’t very useful to you, the Mac’s human companion. They’re there for OS X’s own use (which is why Apple no longer puts the Macintosh HD icon on the desktop of new Macs, as it did for 25 years). Think of your main hard drive window as storage for the operating system itself, which you’ll access only for occasional administrative purposes.

In fact, the folders you really do care about boil down to these:

Applications Folder

Applications is Apple’s word for programs.

When it comes to managing your programs, the Applications folder (which you can open by choosing Go→Applications) is something like the Program Files folder in Windows—but without the worry. You should feel free to open this folder and double-click things. In fact, that’s exactly what you’re supposed to do. This is your complete list of programs. (What’s on your Dock is more like a Greatest Hits subset.)

Better yet, on the Mac, programs bear their real, plain-English names, like Microsoft Word, rather than abbreviations, like WINWORD.EXE. Most are self-contained in a single icon, too (rather than being composed of hundreds of little support files), which makes copying or deleting them extremely easy.

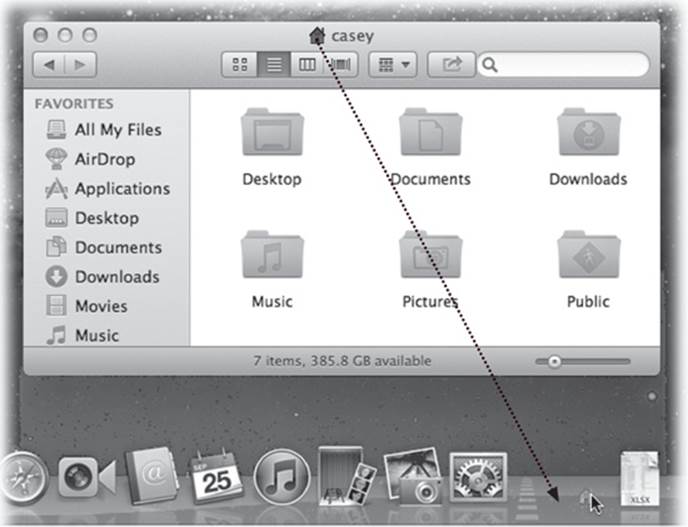

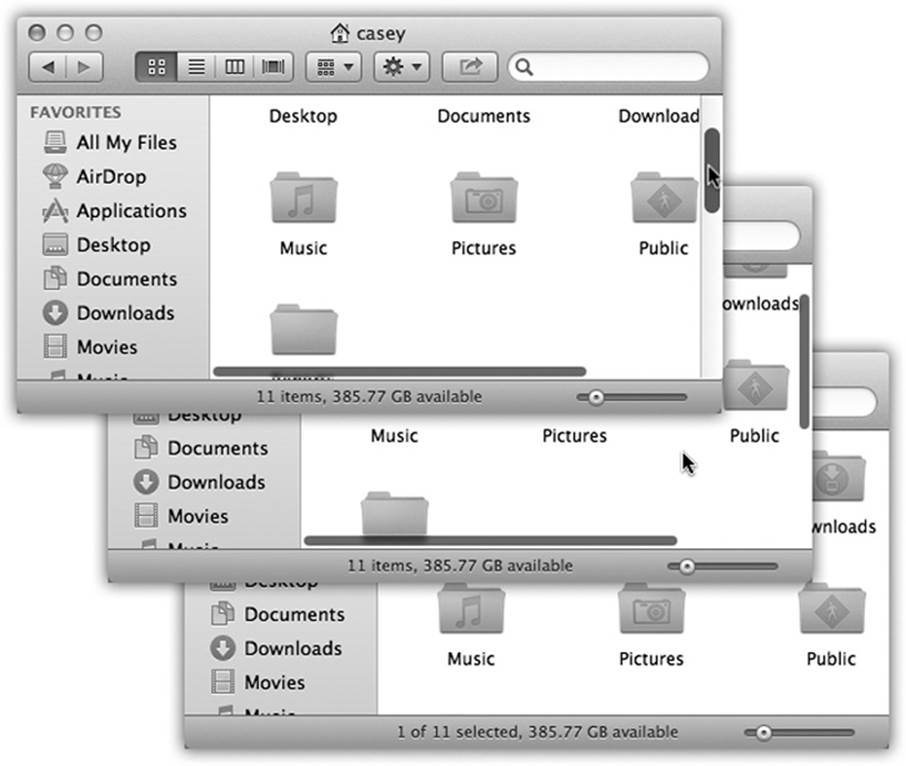

Home Folder

Your documents, files, and preferences, meanwhile, sit in an important folder called your Home folder. Inside are folders that closely resemble the My Documents, My Pictures, and My Music folders on Windows.

OS X is rife with shortcuts for opening this all-important folder:

§ Choose Go→Home.

§ Press Shift-⌘-H.

§ Click the ![]() icon in the Sidebar (Zoom Button). (If you don’t see it there, then choose Finder→Preferences→Sidebar and turn on the

icon in the Sidebar (Zoom Button). (If you don’t see it there, then choose Finder→Preferences→Sidebar and turn on the ![]() checkbox in the list of Places.)

checkbox in the list of Places.)

§ Click the ![]() icon on the Dock.

icon on the Dock.

Within your Home folder, you’ll find another set of standard Mac folders. (You can tell the Mac considers them holy because they have special logos on their folder icons.) Except as noted, you’re free to rename or delete them; OS X creates the following folders solely as a convenience:

§ Desktop. When you drag an icon out of a folder or disk window and onto your OS X desktop, it may appear to show up on the desktop. But that’s just an optical illusion, a visual convenience. In truth, nothing in OS X is really on the desktop. It’s actually in this Desktop folder, and mirrored in the desktop area.

You can entertain yourself for hours by proving this point to yourself. If you drag something out of your Desktop folder, it also disappears from the actual desktop. And vice versa. (You’re not allowed to delete or rename this folder.)

§ Documents. Apple suggests that you keep your actual work files in this folder. Sure enough, whenever you save a new document (when you’re working in Keynote or Word, for example), the Save As box proposes storing the new file in this folder.

Your programs may also create folders of their own here. For example, you may find a Microsoft User Data folder for your Outlook email, a Windows folder for use with Parallels or VMWare Fusion (Chapter 8), and so on.

§ Library. The main Library folder (the one in your main hard drive window) contains folders for your Mac’s system-wide fonts, preferences, help files, and so on.

You have your own Library folder, too. It stores the same kinds of things—but they’re your fonts, your preferences, and so on. It’s generally hidden, although you can get to it by pressing Option as you choose Go→Library.

§ Movies, Music, Pictures. These folders, of course, are designed to store multimedia files. The various OS X programs that deal with movies, music, and pictures will propose these specialized folders as storage locations. For example, when you plug a digital camera into a Mac, the iPhoto program automatically begins to download the photos on it—and stores them in the Pictures folder. Similarly, iMovie is programmed to look for the Movies folder when saving its files, and iTunes stores its MP3 files in the Music folder.

§ Public. If you’re on a network, or if others use the same Mac when you’re not around, this folder can be handy: It’s the “Any of you guys can look at these files” folder. Other people on your network, as well as other people who sit down at this machine, are allowed to see whatever you’ve put in here, even if they don’t have your password. (If your Mac isn’t on an office network and isn’t shared, then you can throw this folder away.) More details on sharing and networking on the Mac are in Chapter 15.

Forcing you to keep all your stuff in a single folder has some major advantages. Most notably, by keeping such tight control over which files go where, OS X keeps itself pure—and very, very stable.

System Folder

This folder is the same idea as the Windows or WINNT folder on a PC, in that it contains hundreds of files that are critical to the functioning of the operating system. These files are so important that moving or renaming them could render the computer useless, as it would in Windows. And although there are thousands of files within, many are hidden for your protection.

For maximum safety and stability, you should ignore OS X’s System folder just as thoroughly as you ignored the old Windows folder.

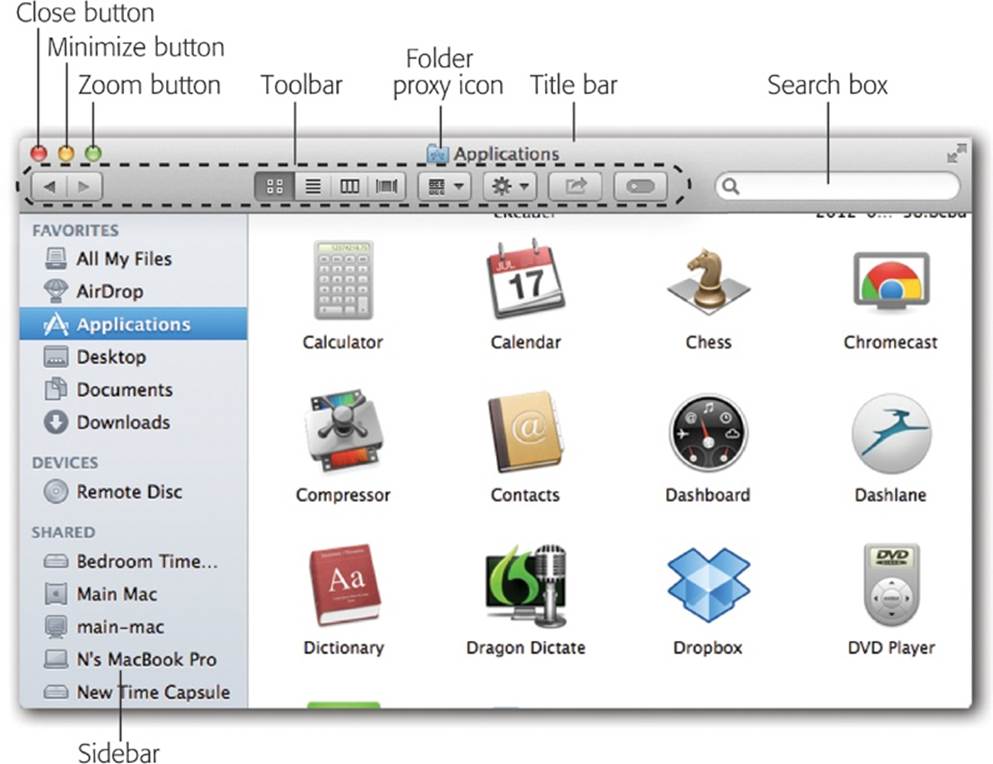

Window Controls

As in Windows, a window on the Mac is framed by an assortment of doodads and gizmos (Figure 1-8). You’ll need these to move a window, to close it, to resize it, to scroll it, and so on. But once you get to know the ones on a Macintosh, you’re likely to be pleased by the amount of thought those fussy perfectionists at Apple have put into their design.

Figure 1-8. When Steve Jobs unveiled Mac OS X at Macworld Expo in 2000, he said his goal was to oversee the creation of an interface so attractive, “you just want to lick it.” Desktop windows, with their juicy, fruit-flavored controls, are a good starting point.

Here’s an overview of the various OS X window-edge gizmos and what they do.

Title Bar

When several windows are open, the darkened window name and colorful upper-left controls tell you which window is active (in front). Windows in the background have gray, dimmed lettering and gray upper-left control buttons. As in Windows, the title bar also acts as a handle that lets you move the entire window around on the screen.

TIP

Here’s a nifty keyboard shortcut with no Windows equivalent: You can cycle through the different open windows in one program without using the mouse. Just press ⌘-` (that’s the tilde key, to the left of the number 1 key). With each press, you bring a different window forward within the current program. It works both in the Finder and in your programs.

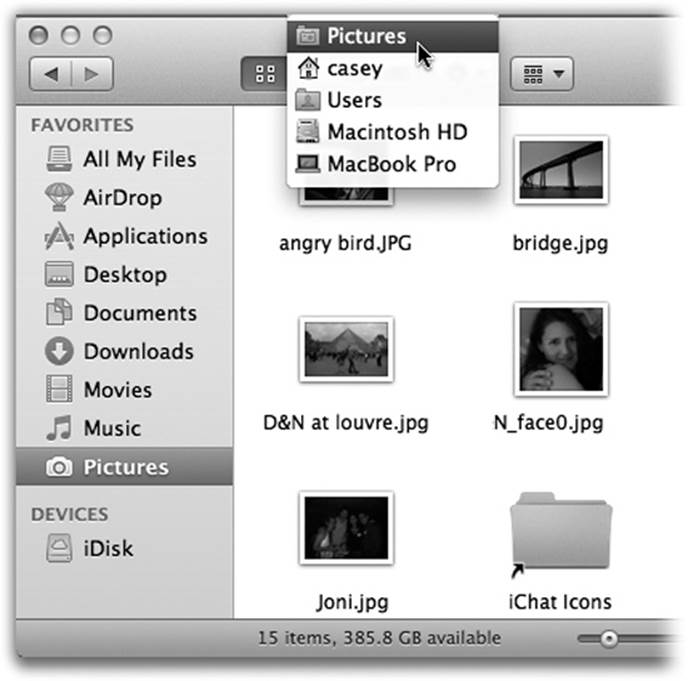

After you’ve opened one folder inside another, the title bar’s secret folder hierarchy menu is an efficient way to backtrack—to return to the enclosing window. Figure 1-9 reveals everything about the process after this key move: pressing the ⌘ key as you click the name of the window. (You can release the ⌘ key immediately after clicking.)

Figure 1-9. Right-click or two-finger click a Finder window’s title bar to summon the hidden folder hierarchy menu. This trick also works in most other OS X programs. For example, you can right-click a document window’s title to find out where the document is actually saved on your hard drive.

One more title bar trick: By double-clicking the title bar, you minimize the window (see Close Button).

The Folder Proxy Icon

Virtually every Macintosh title bar features a small icon next to the window’s name (Figure 1-10), representing the open window’s actual folder or disk icon. In the Finder, dragging this tiny icon (technically called the folder proxy icon) lets you move or copy the folder to a different folder or disk, to the Trash, or into the Dock, without having to close the window first. (When clicking this proxy icon, hold down the mouse button for half a second, or until the icon darkens. Only then are you allowed to drag it.) It’s a handy little function with no Windows equivalent.

TIP

In some programs, including Microsoft Word, dragging this proxy icon lets you move the actual file to a different disk or folder—without even leaving the program. It’s a great way to make a backup of the document you’re working on without interrupting your work.

Figure 1-10. When you find yourself confronting a Finder window that contains useful stuff, consider dragging its proxy icon to the Dock. That will install its folder or disk icon there for future use. It’s not the same as minimizing the window, which puts the window icon into the Dock only temporarily. (Note: Most document windows also offer a proxy-icon feature, but usually only an alias is produced when you drag the proxy to a different folder or disk.)

Close Button

As the tip of your cursor crosses the three buttons at the upper-left corner of a window, tiny symbols appear inside them: ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The most important one is the Close button, the red, droplet-like button in the upper-left corner (see Figure 1-8). It closes the window, exactly like the

. The most important one is the Close button, the red, droplet-like button in the upper-left corner (see Figure 1-8). It closes the window, exactly like the![]() button at the upper-right corner in Windows. Learning to reach for the upper-left corner instead of the upper right will probably confound your muscle memory for the first week of using the Mac.

button at the upper-right corner in Windows. Learning to reach for the upper-left corner instead of the upper right will probably confound your muscle memory for the first week of using the Mac.

If you can’t break the habit, then learn the keyboard shortcut: ⌘-W (for window)—an easier keystroke to type than the Windows version (Alt+F4), which for most people is a two-handed operation. If you get into the habit of dismissing windows with that deft flex of your left hand, you’ll find it far easier to close several windows in a row, because you won’t have to aim for successive Close buttons.

TIP

If, while working on a document, you see a tiny dot in the center of the Close button, OS X is trying to tell you that you haven’t yet saved your work. The dot goes away when you save the document.

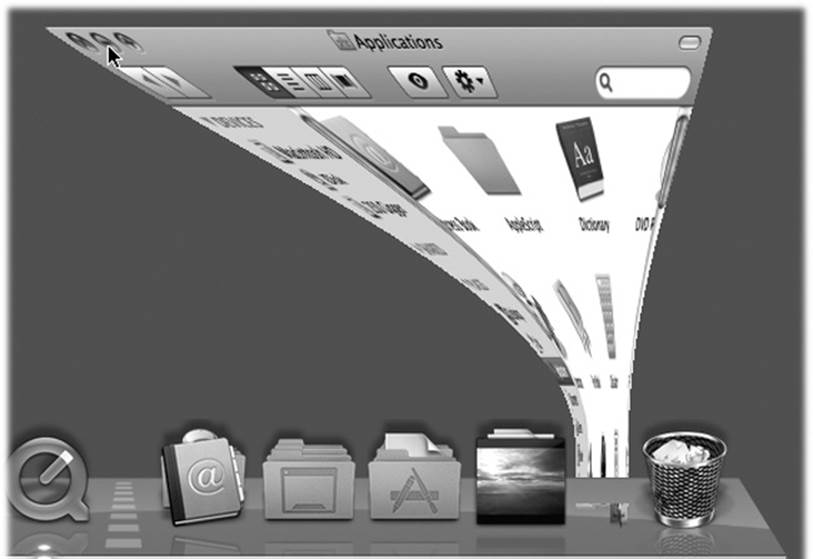

Minimize Button

Click this yellow drop of gel to minimize any Mac window, sending it shrinking, with a genie-like animated effect, into the right end of the Dock, where it now appears as an icon. It’s exactly like minimizing a window in Windows, except that the window is now represented by a Dock icon rather than a taskbar button (Figure 1-11). To bring the window back to full size, click the newly created Dock icon. See Chapter 2 for more on the Dock.

TIP

You actually have a bigger target than the tiny Minimize button. The entire title bar is a giant Minimize button when you double-click anywhere on it. Or just press ⌘-M for Minimize.

Figure 1-11. Clicking the Minimize button sends a window scurrying down to the Dock, collapsing in on itself as though being forced through a tiny, invisible funnel. A little icon appears on the lower-right corner of its minimized image to identify the program it’s running in.

Zoom Button

A click on this green geltab (Figure 1-8) makes a desktop window just large enough to show you all the icons inside it. If your monitor isn’t big enough to show all the icons in a window, then the zoom box resizes the window to show as many as possible. In either case, a second click on the Zoom button restores the window to its original size. (The Window→Zoom Window command does the same thing.)

This should sound familiar: It’s a lot like the Maximize button at the top right of a Windows window. On the Mac, however, the window rarely springs so big that it fills the entire screen, leaving a lot of empty space around the window contents; it grows only enough to show you as much of the contents as possible.

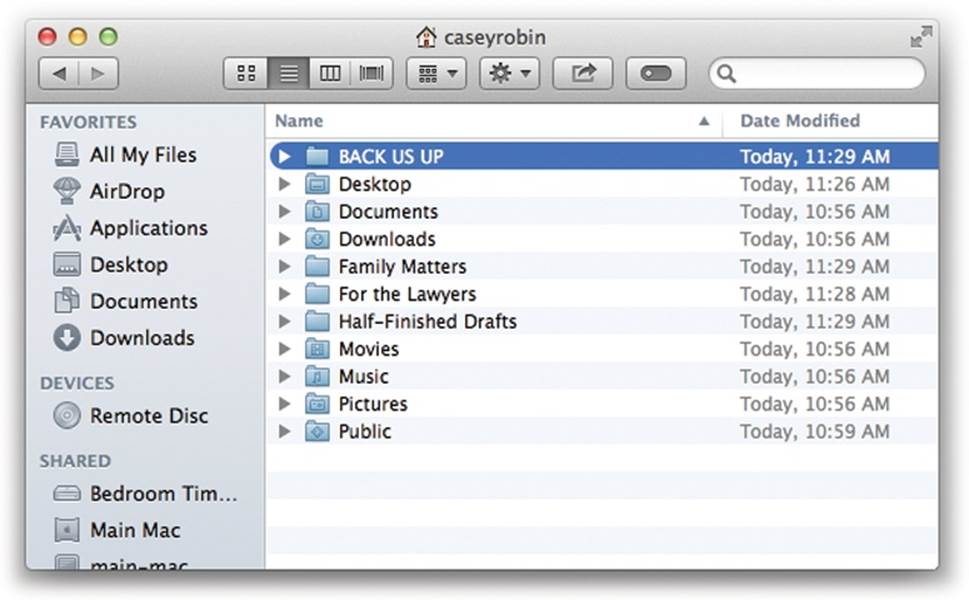

The Finder Sidebar

The Sidebar (Figure 1-12) is the pane at the left side of every Finder window, unless you’ve hidden it. (It’s also at the left side of every Open dialog box and every full-size Save dialog box.) It has as many as three sections, each preceded by a collapsible heading.

TIP

If you point to a heading without clicking, a tiny Hide or Show button appears. Click it to collapse or expand that heading’s contents.

Figure 1-12. Good things to put in the Sidebar: favorite programs, disks on a network you often connect to, or a document you’re working on every day. You can drag a document onto a folder icon to file it there, drag a document onto a program’s icon to open it with the “wrong” program, and so on.

Here are the headings you’ll soon know and love:

§ Favorites. This primary section of the Sidebar is the place to stash things for easy access. You can stock this list with the icons of disks, files, programs, folders, and the virtual, self-updating folders called saved searches.

Each icon is a shortcut. For example, click the Applications icon to view the contents of your Applications folder in the main part of the window. And if you click the icon of a file or a program, it opens.

Here, too, you’ll find the icons for two recent Mac features: All My Files (see the box on the facing page) and AirDrop, the instant-file-sharing feature described on AirDrop.

§ Shared. Here’s a complete list of the other computers on your network whose owners have turned on File Sharing, ready for access (see Chapter 15 for details).

§ Devices. This section lists every storage device connected to, or installed inside, your Mac: hard drives, iPhones, iPads, iPods, CDs, DVDs, memory cards, USB flash drives, and so on. (Your main hard drive doesn’t usually appear here, but you can drag it here.) The removable ones (like CDs, DVDs, i-gadgets) bear a little gray ![]() logo, which you can click to eject that disk.

logo, which you can click to eject that disk.

§ Tags. This section lists all of your Finder tags (color-coded keywords). See Finder Tags for more on tags.

NOTE

If you remove everything listed under one of these headings, the heading itself disappears to save space. The heading reappears the next time you put something in its category back into the Sidebar.

Fine-tuning the Sidebar

The beauty of this parking lot for containers is that it’s so easy to set up with your favorite places. For example:

§ Remove an icon by dragging it out of the Sidebar entirely. It vanishes with a puff of smoke (and even a little whoof sound effect). You haven’t actually removed anything from your Mac; you’ve just unhitched its alias from the Sidebar.

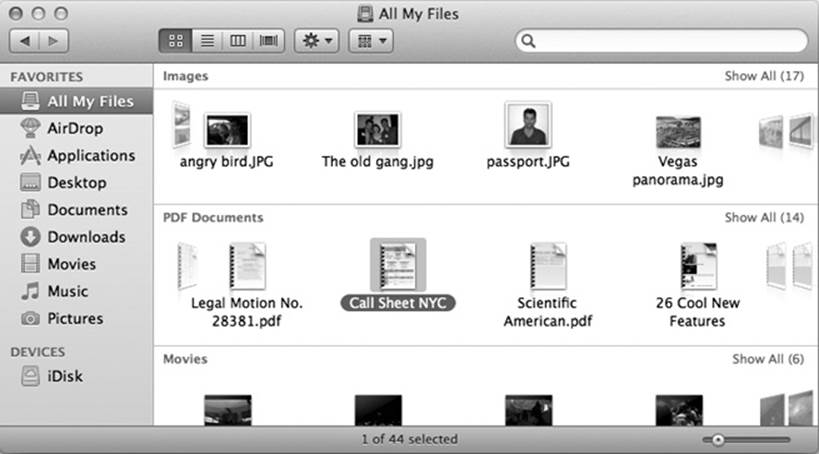

UP TO SPEED: ALL MY FILES

There it is, staring you in the face at the top of the Sidebar in every window: an icon called All My Files. What is this, some kind of geeked-out soap opera?

Nope. It’s a feature that Apple thought you might find handy: a massive, searchable, sortable list, all in a single window, of every human-useful file on the computer. That is, pictures, movies, music, and documents—no system files, preference files, or other detritus. No matter what folders they’re actually in, they appear here in a single window. You can summon it whenever you want, just by clicking the All My Files icon in the Sidebar.

When you first open All My Files, it has your files grouped by type: Contacts, Events & To Dos, Images, PDF Documents, Music, Movies, Presentations, Spreadsheets, Developer (which lists HTML Web-site files and Xcode programming files), and Documents (meaning “everything else”). In icon view—the factory setting—each class of icons appears in a single scrolling row. Use a two-finger scroll (trackpad) or a one-finger slide (Magic Mouse) to move through the horizontal list. (If you’d rather not have to scroll, click the tiny Show All button that appears at the right end of each row. Now you’re seeing all the icons of this type; click Show Less to return to the single-row effect.)

You can see how this sorting method might be useful. Suppose, for example, that you’re looking for a certain PowerPoint or Keynote presentation, but you can’t remember what you called it or where you filed it. Open All My Files, make sure it’s arranged by Kind, and presto: You’re looking at a list of every presentation file on your Mac. Using Quick Look (Quick Look), you can breeze through them, inspecting them one at a time, until you find the one you want.

Apple thinks you’ll like All My Files as a starting point for standard file-fussing operations so much that All My Files is the window that appears automatically when you choose File→New Finder Window (or press ⌘-N). Of course, you can change that in Finder→Preferences.

TIP

You can’t drag items out of the Shared list. Also, if you drag a Devices item out of the list, you’ll have to choose Finder→Preferences→Sidebar and then turn on the appropriate checkbox to put it back in.

§ Rearrange the icons by dragging them up or down in the list. For example, hard drives don’t appear at the top of the Sidebar, but you’re free to drag them into those coveted spots. (You’re not allowed to rearrange the computers listed in the Shared section, though.)

§ Rearrange the sections by dragging them up or down. For example, you can drag Favorites to the bottom but promote the Shared category.

§ Install a new icon by dragging it off your desktop (or out of a window) into any spot in the Favorites list of the Sidebar. Press the ⌘ key after beginning the drag. You can’t drag icons into any section of the Sidebar—just Favorites.

TIP

You can also highlight an icon wherever it happens to be and then choose File→Add to Sidebar, or just press ⌘-T.

§ Adjust the width of the Sidebar by dragging its right edge—either the skinny divider line or the extreme right edge of the vertical scroll bar, if there is one. You “feel” a snap at the point when the line covers up about half of each icon’s name. Any covered-up names sprout ellipses (…) to let you know there’s more (as in “Secret Salaries Spreadsh…”).

§ Hide the Sidebar by pressing ⌘-Option-S, which is the shortcut for the View→Hide Sidebar command. Bring the Sidebar back into view by pressing the same key combination (or by using the Show Sidebar command).

TIP

You can hide and show the Sidebar manually, too: To hide it, drag its right edge all the way to the left edge of the window. Unhide it by dragging the left edge of the window to the right again.

Then again, why would you ever want to hide the Sidebar? It’s one of the handiest navigation aids since the invention of the steering wheel. For example:

§ It takes a lot of pressure off the Dock. Instead of filling up your Dock with folder icons (all of which are frustratingly alike and unlabeled anyway), use the Sidebar to store them. You leave the Dock that much more room for programs and documents.

§ It’s better than the Dock. In some ways, the Sidebar is a lot like the Dock, in that you can stash favorite icons of any sort there. But the Sidebar reveals the names of these icons, and the Dock doesn’t until you use the mouse to point there.

§ It makes ejecting easy. Just click the ![]() button next to any removable disk to make it pop out. (Other ways to eject disks are described on Disk Differences.)

button next to any removable disk to make it pop out. (Other ways to eject disks are described on Disk Differences.)

§ It makes burning easy. When you’ve inserted a blank CD or DVD and loaded it up with stuff you want to copy, click the ![]() button next to its name to begin burning that disc. (Details on burning discs are on Burning CDs and DVDs.)

button next to its name to begin burning that disc. (Details on burning discs are on Burning CDs and DVDs.)

§ You can drag onto its folders and disks. That is, you can drag icons onto Sidebar icons, exactly as though they were the real disks, folders, and programs they represent.

§ It simplifies connecting to networked disks. Park your other computers’ shared folder and disk icons here, as described in Chapter 15, to shave several steps off the usual connecting-via-network ritual.

Window Management

OS X prefers to keep only one Finder window open at a time. That is, if a window called “United States” is filled with folders for the individual states, double-clicking the New York folder doesn’t open a second window. Instead, the New York window replaces the United States window, just as in Windows.

So what if you’ve now opened the New York folder, and you want to backtrack to the United States folder? In that case, just click the tiny ![]() (Back) button or use one of these alternatives:

(Back) button or use one of these alternatives:

§ Choose Go→Back.

§ Press ⌘-[ (left bracket).

§ Press ⌘-![]() .

.

None of that helps you, however, if you want to copy a file from one folder into another, or to compare the contents of the two windows. In such cases, you’ll probably want to see both windows open at the same time.

You can open a second window using any of these techniques:

§ Choose File→New Finder Window (⌘-N).

TIP

The window that appears when you do this is the All My Files window (Fine-tuning the Sidebar), but you can change that setting in Finder→Preferences→General.

§ ⌘-double-click a disk or folder icon.

§ Choose Finder→Preferences→General, and turn on “Always open folders in a new window.” Now when you double-click a folder, it always opens into a new window.

Scroll Bars

A scroll bar, of course, is the traditional window-edge slider that lets you move through a document that’s too big for the window. Without scroll bars in word processors, for example, you’d never be able to write a letter that’s taller than your screen.

Apple expects that you’ll do most of your scrolling on your trackpad, Magic Mouse top surface, or scroll ball/scroll wheel. You almost never use the antiquated method of dragging the scroll bar’s handle manually, with the mouse.

TIP

More reasons nobody uses the mouse to scroll: You can scroll using the keyboard. Your Page Up and Page Down keys let you scroll up and down, one screen at a time, without having to take your hands off the keyboard. The Home and End keys are generally useful for jumping directly to the top or bottom of your document (or Finder window). And if you’ve bought a mouse that has a scroll wheel on the top, you can use it to scroll windows, without pressing any keys at all.

That’s a long-winded way of explaining why, in most programs, the scroll bars are hidden. See Figure 1-13 for details.

NOTE

If the missing scroll bars leave you jittery and disoriented, you can bring them back. Open System Preferences→General and then turn on “Show scroll bars: Always.”

Figure 1-13. In Mavericks, scroll bars don’t appear at all while you’re working (bottom); you have that much more screen area dedicated to your work. If you begin to scroll by sliding your fingers across the trackpad or the Magic Mouse, only the scroll-bar handle appears, so you know where you are (middle). But if you point to the scroll bar, it fattens up so you can operate it more easily (top).

Resizable Edges

You can change the shape of a Macintosh window by dragging its edges, just as in Windows. Just move the mouse carefully to the exact top, bottom, left, or right edge; once its shape changes to a double-headed arrow, you can drag to move that window’s edge in or out.

TIP

If you press the Option key while dragging, you resize the opposite edge simultaneously. For example, if you Option-drag the bottom edge upward, the top edge simultaneously collapses downward.

If you press Shift as you drag, you resize the entire window, retaining its proportions.

And if you Shift-Option drag, you resize the window around its center, rather than from its edges.

Path Bar

This little item appears when you choose View→Show Path Bar. It’s a tiny map at the bottom of the window that shows where you are in the folder hierarchy. If it says Casey→Pictures→Picnic, well, then, you’re looking at the contents of the Picnic folder, which is inside Pictures, which is inside your Home folder (assuming your name is Casey).

TIP

Each tiny folder icon in this display is fully operational. You can double-click it to open it, right-click it to open a shortcut menu, or even drag things into it.

Status Bar

Out of the box, the Mac hides yet another information strip at the bottom of a window—the status bar, which tells you how many icons are in the window (“14 items,” for example) and the amount of free space remaining on the disk. To make it appear, choose View→Show Status Bar.

Terminology Differences

There are enough other differences between Mac and Windows to fill 15 pages. Indeed, that’s what you’ll find at the end of this book: an alphabetical listing of every familiar Windows feature and where to find its equivalent on the Mac.

NOSTALGIA CORNER: HOW THE SCROLL BAR USED TO WORK

If you are that rare, special individual who still operates the scroll bar by clicking it with the mouse, then you’ll be glad to know the old-style controls are still around.

For example: Ordinarily, when you click in the scroll bar track above or below the dark-gray handle bar, the window scrolls by one screenful. But another option awaits when you choose ![]() →System Preferences→General and turn on “Jump to the spot that’s clicked.” Now when you click the scroll-bar track, the Mac considers the entire scroll bar a proportional map of the document and jumps precisely to the spot you clicked. That is, if you click at the very bottom of the scroll-bar track, you see the very last page.

→System Preferences→General and turn on “Jump to the spot that’s clicked.” Now when you click the scroll-bar track, the Mac considers the entire scroll bar a proportional map of the document and jumps precisely to the spot you clicked. That is, if you click at the very bottom of the scroll-bar track, you see the very last page.

No matter which scrolling option you choose in the Appearance panel, you can always override your decision on a case-by-case basis by Option-clicking the scroll-bar track. In other words, if you’ve selected the “Jump to the spot that’s clicked” option, you can produce a “Jump to the next page” scroll by Option-clicking in the scroll-bar track.

As you read both that section of the book and the chapters that precede it, however, you’ll discover that some functions are almost identical in OS X and Windows but have different names. Here’s a quick-reference summary:

|

Windows term |

Macintosh term |

|

Control Panel |

System Preferences |

|

Gadget |

Widget |

|

Drop-down menu |

Pop-up menu |

|

Program |

Application |

|

Properties |

Get Info |

|

Recycle Bin |

Trash |

|

Search command |

Spotlight |

|

Shortcuts |

Aliases |

|

Sidebar |

Dashboard |

|

Taskbar |

Dock |

|

Tray (notification area) |

Menulets |

|

Windows Explorer |

Finder |

|

Windows folder |

System folder |

With that much under your belt, you’re well on your way to learning the ways of OS X.