Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, Mavericks Edition (2014)

Part I. Welcome to Macintosh

Chapter 3. Files, Icons & Spotlight

Every document, program, folder, and disk on your Mac is represented by an icon: a colorful little picture that you can move, copy, or double-click to open. In OS X, icons look more like photos than cartoons, and you can scale them to practically any size.

This chapter is all about manipulating those icons—that is, your files, folders, and disks. It’s all about naming them, copying them, deleting them, labeling them—and then, maybe most important of all, finding them, using the Mac’s famous Spotlight instant-search feature.

Renaming Icons

An OS X icon’s name can have up to 255 letters and spaces. Compared with the 31-character or even eight-character limits of older Windows versions, that’s quite a luxurious ceiling.

As a Windows veteran, furthermore, you may be delighted to discover that in OS X, you can name your files using letters, numbers, punctuation—in fact, any symbol except the colon (:), which the Mac uses behind the scenes for its own folder-hierarchy designation purposes. And you can’t use a period to begin a file’s name.

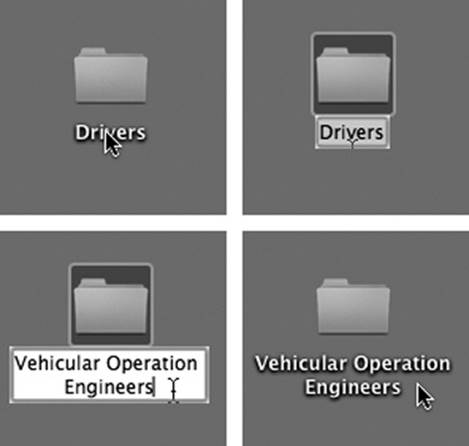

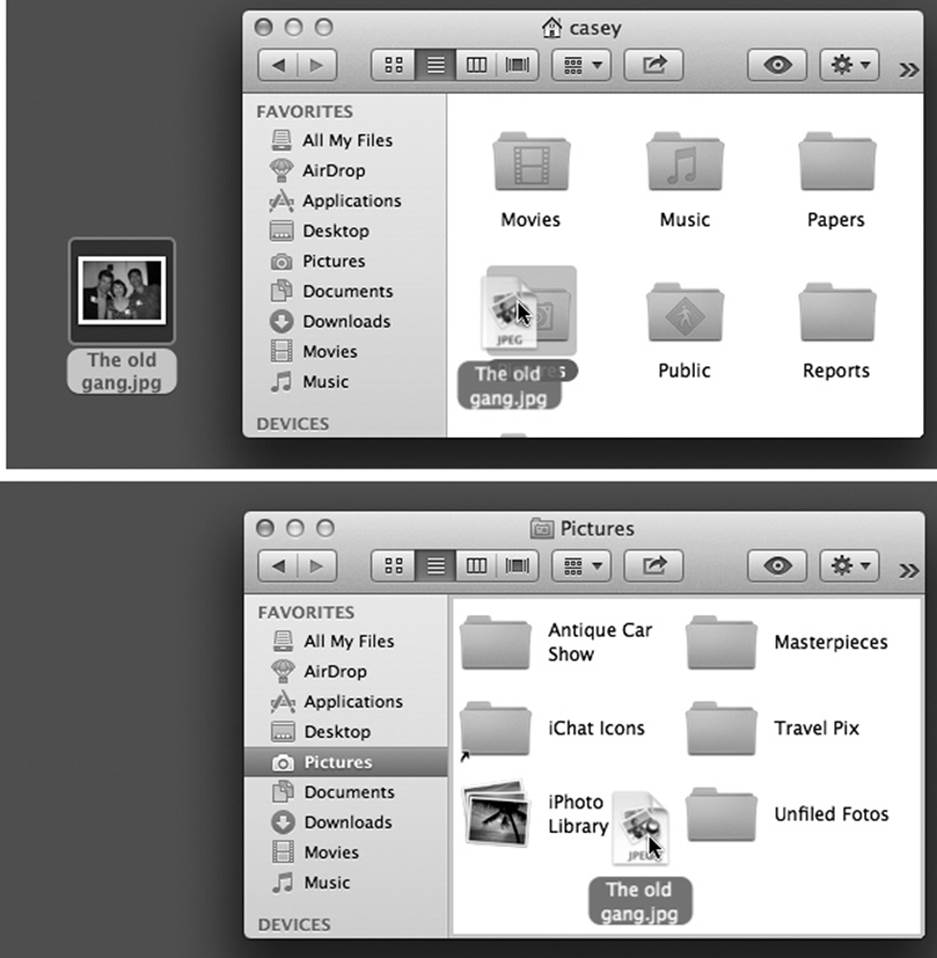

To rename a file, click its name or icon (to highlight it) and then press Return. (Or, if you have time to kill, click once on the name, wait a moment, and then click a second time.)

In any case, a rectangle appears around the name (Figure 3-1). At this point, the existing name is highlighted; just begin typing to replace it. If you type a very long name, the rectangle grows vertically to accommodate new lines of text.

TIP

If you simply want to add letters to the beginning or end of the file’s existing name, press the ![]() or

or ![]() key after pressing Return. The insertion point jumps to the beginning or end of the file name.

key after pressing Return. The insertion point jumps to the beginning or end of the file name.

You can give more than one file or folder the same name, as long as they’re not in the same folder. For example, you can have as many files named “Chocolate Cake Recipe” as you like, provided each is in a different folder. And, of course, files called Recipe.doc and Recipe.xls can coexist in a folder, too.

Figure 3-1. Click an icon’s name (top left) to produce the renaming rectangle (top right), in which you can edit the file’s name. OS X is kind enough to highlight only the existing name, and not the suffix (like .jpg or .doc). Now begin typing to replace the existing name (bottom left). When you’re finished typing, press Return, Enter, or Tab to seal the deal, or just click somewhere else.

As you edit a file’s name, remember that you can use the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands in the Edit menu to move selected bits of text around, just as though you were word processing. The Paste command can be useful when, for instance, you’re renaming many icons in sequence (Quarterly Estimate 1, Quarterly Estimate 2…).

And now, a few tips about renaming icons:

UP TO SPEED: THE WACKY KEYSTROKES OF OS X

OS X offers a glorious assortment of predefined keystrokes for jumping to the most important locations on your Mac: your Home folder, the Applications folder, the Utilities folder, the Computer window, your iDisk, the Network window, and so on.

Better yet, the keystrokes are incredibly simple to memorize: Just press Shift-⌘ and the first letter of the location you want. Shift-⌘-H opens your Home folder, Shift-⌘-A opens the Applications folder, and so on. You learn one, you’ve learned ’em all. The point here is that Shift-⌘ means places.

The other system-wide key combo, Option-⌘, means functions. For example, Option-⌘-D hides or shows the Dock, Option-⌘-H is the Hide Others command, Option-⌘-+ magnifies the screen (if you’ve turned on this feature), Option-⌘-Esc brings up the Force Quit dialog box, and so on. Consistency is always nice.

§ When the Finder sorts files, a space is considered alphabetically before the letter A. To force a particular file or folder to appear at the top of a list-view window, insert a space (or an underscore) before its name.

§ Older operating systems sort files so that the numbers 10 and 100 come before 2, the numbers 30 and 300 come before 4, and so on. You wind up with alphabetically sorted files like this: “1. Big Day,” “10. Long Song,” “2. Floppy Hat,” “20. Dog Bone,” “3. Weird Sort,” and so on. Generations of computer users have learned to put zeros in front of their single-digit numbers just to make the sorting look right.

In OS X, though, you get exactly the numerical list you’d hope for: “1. Big Day,” “2. Floppy Hat,” “3. Weird Sort,” “10. Long Song,” and “20. Dog Bone.”

§ In addition to letters and numbers, OS X also assigns punctuation marks an “alphabetical order,” which is this: ` (the accent mark above the Tab key), ^, _, -, space, –, —, comma, semicolon, !, ?, ‘, “, (, ), [, ], {, }, @, *, /, &, #, %, +, <, =, ≠, ~, >, |, ~, and $.

Numbers come after punctuation; letters come next; and bringing up the rear are these characters: μ (Option-M); π (Option-P); Ω (Option-Z), and ![]() (Shift-Option-K).

(Shift-Option-K).

§ When it comes time to rename files en masse, add-on shareware can help you. A Better Finder Rename, for example, lets you manipulate file names in a batch—numbering them, correcting a spelling in dozens of files at once, deleting a certain phrase from their names, and so on. You can download this shareware from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

Selecting Icons

To highlight a single icon in preparation for printing, opening, duplicating, or deleting, click the icon once. Both the icon and the name darken in a uniquely OS Xish way.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTION: PRINTING A WINDOW—OR A LIST OF FILES

In Mac OS 9, I could print a Finder window. I’d get a neat list of the files, which I could use as a label for a CD I was going to burn, or whatever. How do I print a Finder window in OS X? (The File→Print command prints a selected document, not the list of files in a window.)

It’s easy enough to make a list of files for printing. Once the window is open on your screen, choose Edit→Select All. Choose Edit→Copy. Now switch to a word processor and paste. (If you’re using TextEdit, use Edit→Paste and Match Style instead.) You get a tidy list of all the files in that window, ready to format and print.

This simple file name list isn’t the same as printing a window; you don’t get the status bar showing how many items are on the disk and how full the disk is. For that purpose, you can always make a screenshot of the window (RealPlayer) and print that. Of course, that technique is no good if the list of files is taller than the window itself.

Really, what you want is Print Window, a handy shareware program that’s dedicated to printing your Finder windows, without all these workarounds and limitations. You can download it from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

That much may seem obvious. But most first-time Mac users have no idea how to manipulate more than one icon at a time—an essential survival skill in a graphic interface like the Mac’s.

Selecting by Clicking

To highlight multiple files in preparation for moving or copying, use one of these techniques:

§ Highlight all the icons. To select all the icons in a window, press ⌘-A (the equivalent of the Edit→Select All command).

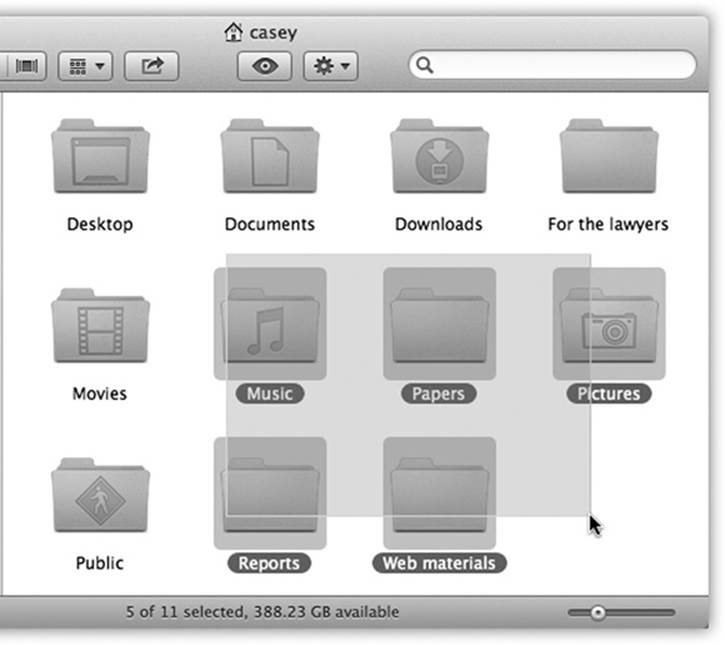

§ Highlight several icons by dragging. You can drag diagonally to highlight a group of nearby icons, as shown in Figure 3-2. In a list view, in fact, you don’t even have to drag over the icons themselves—your cursor can touch any part of a file’s row, like its modification date or file size.

TIP

If you include a particular icon in your diagonally dragged group by mistake, ⌘-click it to remove it from the selected cluster.

Figure 3-2. You can highlight several icons simultaneously by dragging a box around them. To do so, drag from outside the target icons diagonally across them, creating a translucent gray rectangle as you go. Any icons or icon names touched by this rectangle are selected when you release the mouse. If you press the Shift or ⌘ key as you do this, then any previously highlighted icons remain selected.

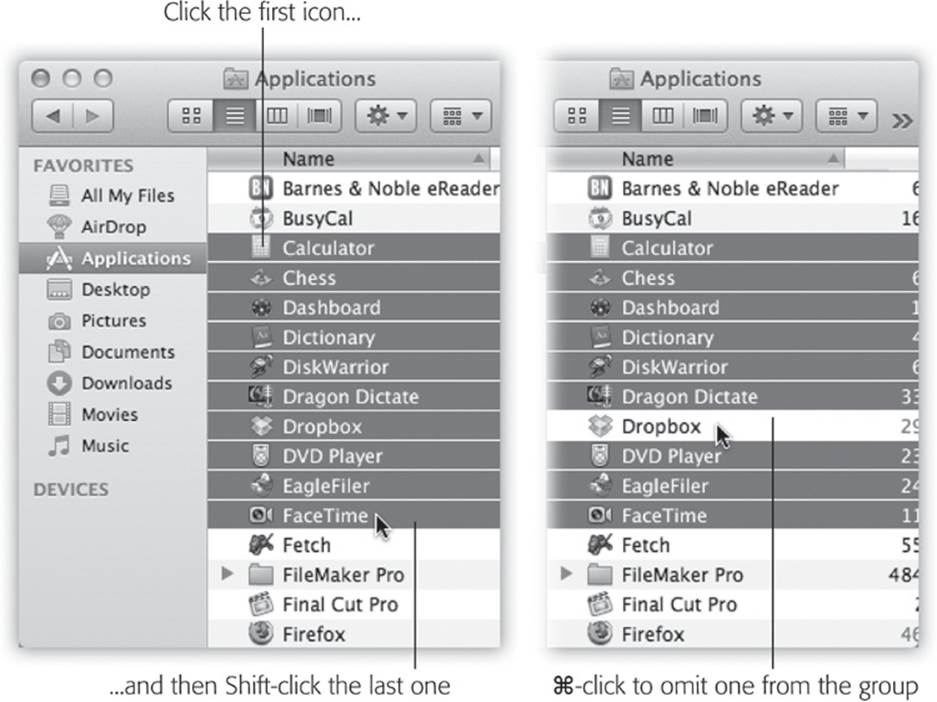

§ To highlight consecutive icons in a list. If you’re looking at the contents of a window in list view or column view, you can drag vertically over the file and folder names to highlight a group of consecutive icons, as described above. (Begin the drag in a blank spot.)

There’s a faster way to do the same thing: Click the first icon you want to highlight, and then Shift-click the last file. All the files in between are automatically selected, along with the two icons you clicked. Figure 3-3 illustrates the idea.

Figure 3-3. Left: To select a block of files in list view, click the first icon. Then, while pressing Shift, click the last one. OS X highlights those files and all the files in between your clicks. This technique mirrors the way Shift-clicking works in a word processor and in many other kinds of programs. Right: To remove one of the icons from your selection, ⌘-click it.

§ To highlight random icons. If you want to highlight only the first, third, and seventh icons in a window, for example, start by clicking icon No. 1. Then ⌘-click each of the others (or ⌘-drag new rectangles around them). Each icon darkens to show that you’ve selected it.

If you’re highlighting a long string of icons and click one by mistake, you don’t have to start over. Instead, just ⌘-click it again so the dark highlighting disappears. (If you do want to start over, you can deselect all selected icons by clicking any empty part of the window—or by pressing the Esc key.) The ⌘ key trick is especially handy if you want to select almost all the icons in a window. Press ⌘-A to select everything in the folder, and then⌘-click any unwanted icons to deselect them.

TIP

In icon view, you can either Shift-click or ⌘-click to select multiple individual icons. But you may as well just learn to use the ⌘ key when selecting individual icons. That way you won’t have to use a different key in each view.

Once you’ve highlighted multiple icons, you can manipulate them all at once. For example, you can drag them en masse to another folder or disk by dragging any one of the highlighted icons. All other highlighted icons go along for the ride. This technique is especially useful when you want to back up a bunch of files by dragging them onto a different disk, delete them all by dragging them to the Trash, and so on.

When multiple icons are selected, the commands in the File and Edit menus—like Duplicate, Open, and Make Alias—apply to all of them simultaneously.

TIP

Don’t forget that you can instantly highlight all the files in a window (or on the desktop) by choosing Edit→Select All (⌘-A)—no icon-clicking required.

Selecting Icons from the Keyboard

For the speed fanatic, using the mouse to click an icon is a hopeless waste of time. Fortunately, you can also select an icon by typing the first few letters of its name.

When looking at your Home window, for example, you can type M to highlight the Movies folder. And if you actually intended to highlight the Music folder instead, then press the Tab key to highlight the next icon in the window alphabetically. Shift-Tab highlights the previous icon alphabetically. Or use the arrow keys to highlight a neighboring icon.

(The Tab-key trick works only in icon, list, and Cover Flow views—not column view, alas. You can always use the ![]() and

and ![]() keys to highlight adjacent columns, however.)

keys to highlight adjacent columns, however.)

After highlighting an icon this way, you can manipulate it using the commands in the File menu or their keyboard equivalents: Open (⌘-O), put it into the Trash (⌘-Delete), Get Info (⌘-I), Duplicate (⌘-D), or make an alias (⌘-L), as described later in this chapter. By turning on the special disability features described on New Folder with Selection, you can even move the highlighted icon using only the keyboard.

If you’re a first-time Mac user, you may find it excessively nerdy to memorize keystrokes for jobs the mouse can do. If you make your living using the Mac, however, memorizing these keystrokes will reward you immeasurably with speed and efficiency.

Moving and Copying Icons

In OS X, there are two ways to move or copy icons from one place to another: by dragging them and by using the Copy and Paste commands.

Copying by Dragging

You can drag icons from one folder to another, from one drive to another, from a drive to a folder on another drive, and so on. (When you’ve selected several icons, drag any one of them; the others tag along.) As you drag, you see the ghostly images of all the selected icons moving with your cursor. And the cursor itself sprouts a circled number that reminds you how many files you’re moving.

TIP

You can tell that the copying is under way even if the progress bar is hidden. In Mavericks, a tiny progress bar appears right on the icon of the copied material in its new home. You can cancel the process either by pressing ⌘-period or by clicking the ![]() in the progress window.

in the progress window.

Understanding when the Mac copies a dragged icon and when it moves it bewilders many a beginner. However, the scheme is fairly simple when you consider the following:

§ On a single disk, dragging from one folder to another moves the icon.

§ Dragging from one disk (or disk partition) to another copies the folder or file. (You can drag icons either into an open window or directly onto a disk or folder icon.)

§ If you press the Option key as you release an icon you’ve dragged, you copy the icon instead of moving it. Doing so within a single folder produces a duplicate of the file called “[Whatever its name was] copy.”

§ If you press the ⌘ key as you release an icon you’ve dragged from one disk to another, you move the file or folder, in the process deleting it from the original disk.

NOTE

This business of pressing Option or ⌘ after you begin dragging is a tad awkward, but it has its charms. For example, it means you can change your mind about the purpose of your drag in mid-movement, without having to drag back and start over.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: SMART HANDLING OF IDENTICALLY NAMED ICONS

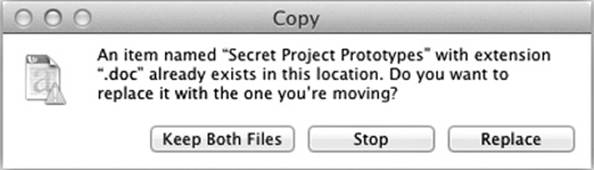

What if you’re dragging a file or folder into some window—and there’s already a file or folder there with the same name?

In operating systems in days of yore, a warning message appeared. It let you Stop (the whole operation) or Replace (the existing items with the ones you were moving).

OS X is just a little bit smarter. It offers a third option: Keep Both.

For example, if you drag or paste files of the same name, you’re offered a button called Keep Both Files. If you click it, OS X adds the number 2 (or 3, or 4…) to the end of the incoming file’s name, so you can tell it apart from the existing one in the destination.

Tip: If you’re dragging several files whose names match existing files in the destination folder, then OS X asks you individually about each one (Stop, Replace, Keep Both Files?). If you intend to answer the same way for every single file, save yourself the insanity by turning on the “Apply to all” checkbox before answering the question.

There’s another, related feature that comes into play when you paste a folder into a spot where there’s another folder with the same name. In this case, the Mac offers to merge the contents of the two folders.

It might say, for example: “An item named ‘Notes’ already exists in this location. Do you want to replace it with the one you’re moving? Each folder has unique items such as ‘Salary Projections’ and ‘Stealth Projects.doc.’ ” And your choices are Stop, Keep Both, or Replace All. (These options appear only when you’re pasting a folder into a new window—not dragging it. They also appear when you Option-drag a folder into a new window to copy it there, or when you drag it to a different disk.)

If you click Keep Both, the Finder combines the contents of the two folders. The folder you’re pasting disappears, but its contents join the contents of the other folder (the one in the destination window) in blissful harmony.

And if it turns out you just dragged something into the wrong window or folder, a quick ⌘-Z (the shortcut for Edit→Undo) puts it right back where it came from.

Copying or Moving with Copy and Paste

Dragging icons to copy or move them probably feels good because it’s so direct: You actually see your arrow cursor pushing the icons into the new location.

But you pay a price for this satisfying illusion. You may have to spend a moment or two fiddling with your windows to create a clear “line of drag” between the icon to be moved and the destination folder. (A background window will courteously pop to the foreground to accept your drag. But if it wasn’t even open to begin with, you’re out of luck.)

There’s a better way. Use Copy and Paste to move icons from one window into another.

The routine goes like this:

1. Highlight the icon or icons you want to move.

Use any of the techniques described starting on Selecting Icons.

2. Choose Edit→Copy.

Or press the keyboard shortcut: ⌘-C.

TIP

You can combine steps 1 and 2 by right-clicking (two-finger clicking) an icon and choosing the Copy command from the shortcut menu that appears—or by using the ![]() menu. If you’ve selected several icons, say five, then the command says, “Copy 5 items.”

menu. If you’ve selected several icons, say five, then the command says, “Copy 5 items.”

3. Open the window where you want to put the icons. Choose Edit→Paste.

Once again, you may prefer to use the keyboard equivalent: ⌘-V. And once again, you can also right-click or two-finger click inside the window and then choose Paste from the shortcut menu that appears, or you can use the ![]() menu.

menu.

If you add the Option key—press Option-⌘-V—you move the icons to the new window instead of copying them. That is, the originals disappear after they appear in the new location, exactly as though you’d used the Cut command in Windows. (This might make more sense if you use the menu way: If you open the Edit menu and press Option, you’ll see the Paste Items command change to say Move Items Here.) It took 27 years, but you can finally cut and paste icons, just as in Windows.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTION: DRAGGING TO COPY A DISK

Help! I’m trying to copy a CD onto my hard drive. When I drag it onto the hard drive icon, I get only an alias—not a copy of the CD.

Sure enough, dragging a disk onto a disk creates an alias.

But producing a copy of the dragged icon is easy enough: Just press Option or ⌘ as you drag.

Honestly, though: Why are you trying to copy a CD this way? Using Disk Utility (Disk Utility) saves space, lets you assign a password, and usually fools whatever software was on the CD into thinking that it’s still on the original CD.

You can press ⌘-period to interrupt the process. When the progress bar goes away, it means you’ve successfully transferred the icons, which now appear fully fleshed in the new window.

Spring-Loaded Folders: Dragging Icons into Closed Folders

Here’s a common dilemma: You want to drag an icon not just into a folder, but into a folder nested inside that folder. This awkward challenge would ordinarily require you to open the folder, open the inner folder, drag the icon in, and then close both windows. As you can imagine, the process is even messier if you want to drag an icon into a sub-subfolder or a sub-sub-subfolder.

Instead of fiddling around with all those windows, you can instead use the spring-loaded folders feature (Figure 3-4).

It works like this: With a single drag, drag the icon onto the first folder—but keep your mouse button pressed. After a few seconds, the folder window opens automatically, centered on your cursor. In icon and Cover Flow views, the new window instantly replaces the original. In column view, you get a new column that shows the target folder’s contents. In list view, a second window appears.

Still keeping the button down, drag onto the inner folder; its window opens, too. Now drag onto the inner inner folder—and so on. (If the inner folder you intend to open isn’t visible in the window, you can scroll by dragging your cursor close to any edge of the window.)

TIP

You can even drag icons onto disks or folders whose icons appear in the Sidebar (Chapter 1). When you do so, the main part of the window flashes to reveal the contents of the disk or folder you’ve dragged onto. When you let go of the mouse, the main window changes back to reveal the contents of the disk or folder where you started dragging.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: ICON’S PROGRESS: THE LEAST-MARKETED FEATURE IN OS X

Here’s an unsung little Mac feature: When you’re copying a file or a folder, a tiny progress bar appears right on the icons as they sit in their new location. Animated and everything!

Doesn’t matter if it’s list view, icon view, or what—you’ll see the progress bar.

You’ll also see the little ![]() button at the top left corner. That, of course, means “click me to cancel this copying job, since you obviously don’t know about the ⌘-period keystroke.”

button at the top left corner. That, of course, means “click me to cancel this copying job, since you obviously don’t know about the ⌘-period keystroke.”

Think of it as a little bit of mistake-recovery insurance, finally on the Mac after almost 30 years.

In short, Sidebar and spring-loaded folders make a terrific drag-and-drop way to move an icon from anywhere to anywhere—without having to open or close any windows at all.

Figure 3-4. Top: To make spring-loaded folders work, start by dragging an icon onto a folder or disk icon. Don’t release the mouse button. Wait for the window to open automatically around your cursor. Bottom: Now you can either let go of the mouse button to release the file in its new window or drag it onto yet another, inner folder. It, too, will open. As long as you don’t release the mouse button, you can continue until you’ve reached your folder-within-a-folder destination.

When you finally release the mouse, you’re left facing the final window. All the previous windows closed along the way. You’ve placed the icon into the depths of the nested folders.

Making Spring-Loaded Folders Work

That spring-loaded folder technique sounds good in theory, but it can be disconcerting in practice. For most people, the long wait before the first folder opens is almost enough wasted time to negate the value of the feature altogether. Furthermore, when the first window finally does open, you’re often caught by surprise. Suddenly your cursor—mouse button still down—is inside a window, sometimes directly on top of another folder you never intended to open.

Fortunately, you can regain control of spring-loaded folders using these tricks:

§ Choose Finder→Preferences. On the General pane, adjust the “Spring-loaded folders and windows” delay slider to a setting that drives you less crazy. For example, if the first folder takes too long to open, then drag the slider toward the Short setting. Or turn off this feature entirely by turning off the “Spring-loaded folders and windows” checkbox.

§ Tap the space bar to make the folder spring open at your command. That is, even with the Finder→Preferences slider set to the Long delay setting, you can force each folder to spring open when you are ready by tapping the space bar as you hold down the mouse button. True, you need two hands to master this one, but the control you regain is immeasurable.

§ Whenever a folder springs open into a window, twitch your mouse up to the opened window’s title bar. With the cursor parked on the gradient gray, you can take your time to get your bearings before plunging into an inner folder.

TIP

Email programs like Outlook and Mail have spring-loaded folders, too. You can drag a message out of the list and into one of your filing folders, wait for the folder to spring open and reveal its subfolders, and then drag it directly into one of them.

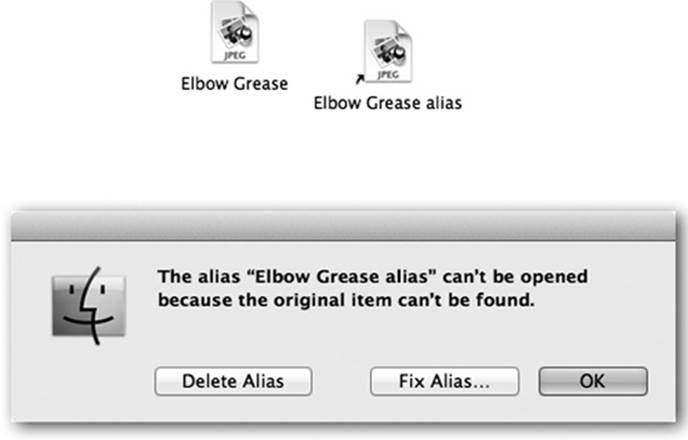

Aliases: Icons in Two Places at Once

Highlighting an icon and then choosing File→Make Alias (or pressing ⌘-L) generates an alias, a specially branded duplicate of the original icon (Figure 3-5). It’s not a duplicate of the file—just of the icon; therefore it requires negligible storage space.

Figure 3-5. Top: You can identify an alias by the tiny arrow badge on the lower-left corner. (Longtime Mac fans should note that the name no longer appears in italics.) Bottom: If the alias can’t find the original file, you’re offered the chance to hook it up to a different file.

When you double-click the alias, the original file opens. (A Macintosh alias is essentially the same as a Windows shortcut.)

You can create as many aliases as you want of a single file; therefore, in effect, aliases let you stash that file in many different folder locations simultaneously. Double-click any one of them and you open the original file, wherever it may be on your system.

TIP

You can also create an alias of an icon by Option-⌘-dragging it out of its window. (Aliases you create this way lack the word alias on the file name—a delight to those who find the suffix redundant and annoying.) You can also create an alias by right-clicking or two-finger clicking a normal icon and choosing Make Alias from the shortcut menu that appears, or by highlighting an icon and then choosing Make Alias from the ![]() menu.

menu.

What’s Good about Aliases

An alias takes up very little disk space, even if the original file is enormous. Aliases are smart, too: Even if you rename the alias, rename the original file, move the alias, and move the original around on the disk, double-clicking the alias still opens the original file.

Here are a couple of ways you can put aliases to work:

§ You can file a document you’re working on in several different folders, or place a particular folder in several different locations, for convenience.

§ You can use the alias feature to save you some of the steps required to access another hard drive on the network. (Details on this trick are on Connection Method B: Connect to Server.)

TIP

OS X makes it easy to find the file an alias “points to” without actually having to open it. Just highlight the alias and then choose File→Show Original (⌘-R), or choose Show Original from the ![]() menu. OS X immediately displays the actual, original file, sitting patiently in its folder, wherever that may be.

menu. OS X immediately displays the actual, original file, sitting patiently in its folder, wherever that may be.

Broken Aliases

An alias doesn’t contain any of the information you’ve typed or composed in the original file. Don’t email an alias to the Tokyo office and then depart for the airport, hoping to give the presentation upon your arrival in Japan. When you double-click the alias, now separated from its original, you’ll be shown the dialog box at the bottom of Figure 3-5.

If you find yourself 3,000 miles away from the hard drive on which the original file resides, click Delete Alias (to delete the orphan alias) or OK (to do nothing, leaving it where it is).

In certain circumstances, however, the third button—Fix Alias—is the most useful. Click it to summon the Fix Alias dialog box, which you can use to navigate the folders on your Mac. When you click a new icon and then click Choose, you associate the orphaned alias with a different file.

Such techniques become handy when, for example, you click your book manuscript’s alias on the desktop, forgetting that you recently saved it under a new name and deleted the older draft. Instead of simply showing you an error message that says “ ‘Enron Corporate Ethics Handbook’ can’t be found,” the Mac displays the box that contains the Fix Alias button. By reassociating the alias with the new document, you can save yourself the trouble of creating a new alias. From now on, double-clicking your manuscript’s alias on the desktop opens the new draft.

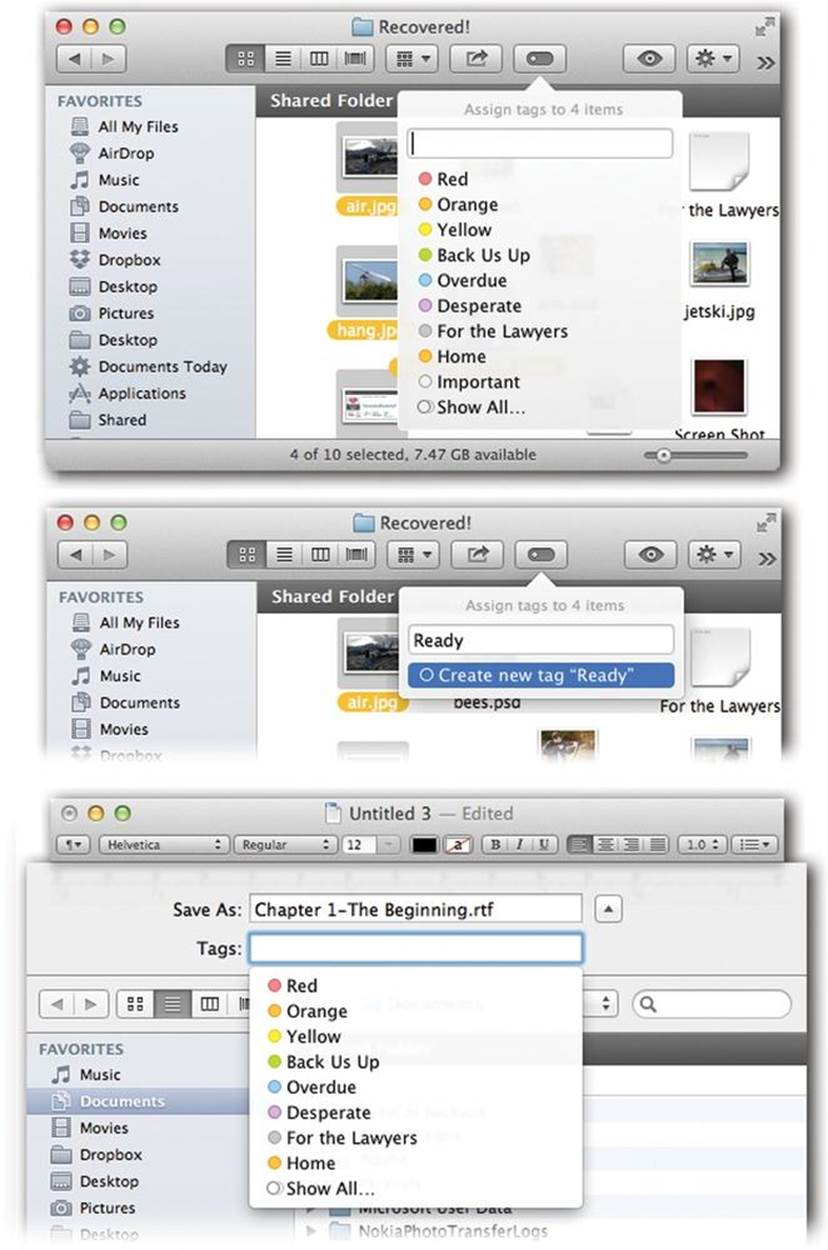

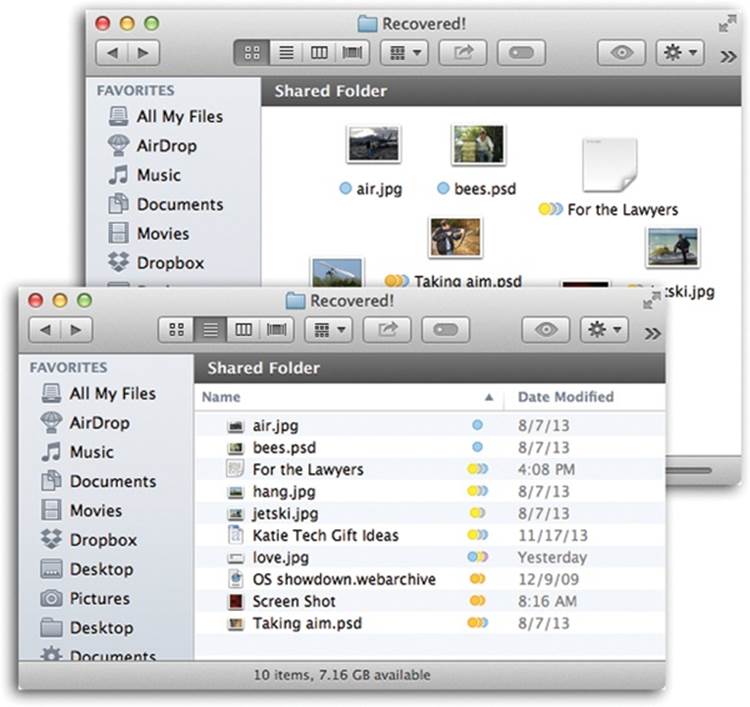

Finder Tags

Here it is, one of the big-ticket new features in Mavericks: Finder tags. They offer a way to color-code, or apply a keyword to, your icons (Figure 3-6). Finder tags are a lot like the Finder labels that have been on the Mac for decades, with a few differences:

§ You can apply more than one tag to an icon, in effect letting it be in more than one place, or sortable in more than one way. A photo of Aunt Edna in her early days on the farm could be tagged Relatives, Photos, and Ancient History.

§ You can have more than seven of them; in fact, you can have dozens (although you can choose from only seven colors).

§ You can create, assign, and use tags in many more ways, in many more places, than you could labels. For example, you can assign a label or two to a new document as you’re naming and saving it.

§ Tags sync. That is, if you have more than one Mac, and they’re signed into the same iCloud account, the same tags are available on all your machines.

What Tags Are Good For

After you’ve applied tags to icons, you can perform some unique file-management tasks—in some cases on all of them simultaneously, even if they’re scattered across multiple hard drives. For example:

§ Round up files with Find. Using the Spotlight search command described in Chapter 3, you can round up all the icons with a particular tag, no matter which folders they’re in.

§ Sort a list view by tag. No other Mac sorting method lets you create an arbitrary order for the icons in a window. When you sort by tag, the Mac creates alphabetical clusters within each tag grouping.

This technique might be useful when, for example, your job is to process several different folders of documents; for each folder, you’re supposed to convert graphics files, throw out old files, or whatever. As soon as you finish working your way through one folder, flag it with a tag called Done. The folder jumps to the top (or bottom) of the window, safely marked for your reference pleasure, leaving the next unprocessed folder at your fingertips, ready to go.

TIP

In a list view, the quickest way to sort by tag is to first make the tag column visible. Do so by choosing View→Show View Options and then turning on the Tags checkbox.

Figure 3-6. Use the File menu, ![]() menu, or shortcut menu to apply label tags to highlighted icons. You can even apply a label within an icon’s Get Info dialog box. Middle: The same menu is your opportunity to create (and simultaneously apply) a new tag. Just type it. Bottom: You can also apply a tag—or even create a new one—at the moment you’re saving a new document. Just type the new tag names into the Tags box that appears just below the Save As box.

menu, or shortcut menu to apply label tags to highlighted icons. You can even apply a label within an icon’s Get Info dialog box. Middle: The same menu is your opportunity to create (and simultaneously apply) a new tag. Just type it. Bottom: You can also apply a tag—or even create a new one—at the moment you’re saving a new document. Just type the new tag names into the Tags box that appears just below the Save As box.

§ Track progress. Use different-colored tags to track the status of files in a certain project. For example, the first drafts have no tags at all. Once they’ve been edited and approved, make them blue. Once they’ve been sent to the home office, make them purple.

(Heck, you could have all kinds of fun with this: Money-losing projects get red tints; profitable ones get green; things that make you sad are blue. Or not.)

Creating Tags

Apple starts you out with a few handy tags, ready to apply to any files you like. They come with ingenious names like Red, Yellow, Blue, and Gray.

If you upgraded your Mac from an earlier version of OS X, you’ll find your old Finder labels magically reincarnated as tags, too.

But to create a new tag, use one of the techniques shown in Figure 3-6. You’re simultaneously creating a new tag and applying it to the file(s) in question. The new tag will be available later in the regular Tags menus.

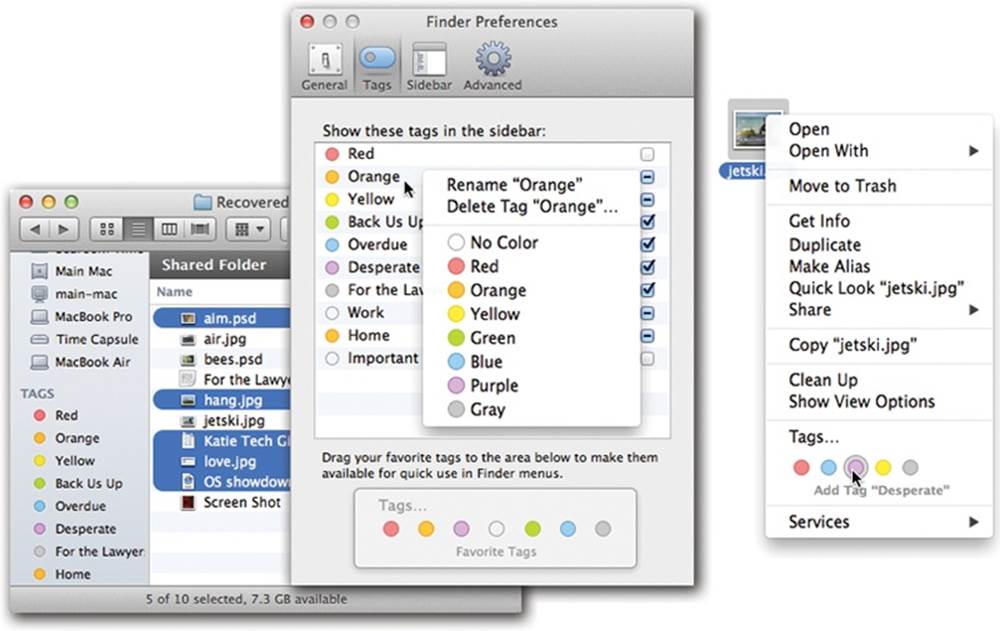

Editing Tag Names and Colors

To change a tag’s name, reassign it to a different color, or delete the tag entirely, open the Tags tab of the Preferences dialog box, as shown in Figure 3-7.

TIP

Actually, an identical set of controls appears when you right-click (or two-finger click) one of the tags that appears in the Sidebar of any Finder window.

Figure 3-7. Middle: In Finder→Preferences→Tags, you can right-click a tag for the shortcut menu shown here. It lets you rename a tag, delete it, or choose a different color. Left: You can install some favored tags in the Sidebar. Right: An even smaller set of favorites appears in Finder menus and shortcut menus.

Two Sets of Favorite Tags

Apple is prepared for Tagageddon; it’s created a system that could lead some people to create hundreds of tags. That number, of course, is a bit unwieldy. Fortunately, Apple has also equipped you with not one but two sets of “favorites.”

§ Sidebar favorites. In Mavericks, the Sidebar at the left side of each Finder window has a section reserved exclusively for displaying the tags you use the most (Figure 3-7, left). To choose which tags you want installed here, open the Preferences dialog box shown in Figure 3-7 and turn on the corresponding checkboxes. (Turn off a checkbox to remove its tag from the Sidebar, of course.)

§ Menu favorites. As shown in Figure 3-7 at right, there’s room for only a few favorite tags—their colored dots, anyway—right in the File→Tags menu, or the shortcut menu that appears when you right-click or two-finger click an icon.

So how do you choose which tags get these exalted positions? In the dialog box shown in Figure 3-7 (middle), drag each favored tag’s name into the Favorite Tags box at bottom. (You can remove one by dragging its dot out of that box.)

Applying Tags

To apply a tag to a file, highlight the file(s), and then do one of the following:

§ Choose from a menu. Right-click (or two-finger click) an icon in the Finder or click the ![]() button at the top of the Finder window (Figure 3-6, middle). Or choose File→Tags.

button at the top of the Finder window (Figure 3-6, middle). Or choose File→Tags.

In each case, you get to see colored dots representing the “menu favorite” tags in your arsenal, as described above. Or you can click Show All to see the complete scrolling list of dozens. (You can apply multiple tags to a single icon.)

§ Use the Sidebar. You can drag Finder icons onto the names of tags in the Sidebar.

§ Apply while saving. You can tag a file as you’re saving it (Figure 3-6, bottom).

§ Apply in the Get Info box. See Locked Files.

§ Apply within the app. Certain Apple programs, like TextEdit, Pages, Numbers, and Keynote, bear a tiny triangle next to the document’s name on the title bar. You can click it to open a Tags box, which lets you edit a document’s tags while you’re still working on it.

§ Hit a keystroke. The Spotlight Menu describes how you can assign keystrokes to common Mac menu commands. As it turns out, the File→Tags command is available for assignment, too. Give it, say, Control-T, and from now on you can call up the Tags dialog box without even taking your fingers off the keyboard.

For the application name, use Finder; for the menu title, type Tags… (press Option-semicolon to produce that three-dot ellipsis, not three periods).

Once you’ve applied a tag, you can see it in the Finder. It’s represented as a colored dot preceding the file’s name; see Figure 3-8.

Figure 3-8. In Mavericks, a tag no longer changes the background color of an icon’s name, as labels once did. That’s because you can now apply more than one tag to a single icon. Instead, tags show up as colored dots—and if you’ve applied more than one, they show up as stacked, side-by-side colored dots.

Using Tags

OK. So you sat up all weekend, painstakingly tagging each of your thousands of files. Now comes the payoff: using tags.

§ Find them all with a click. Click one of the tag names in the sidebar (Figure 3-7, left). You’ve instantly performed a Mac-wide search for all files with that tag. They appear in a single search-results window, regardless of where they’re actually sitting on your computer.

§ Find them all using the Find box. Type a few letters of the tag’s name in the Find box at the top-right corner of any Finder window. Use the “Tags” search token (Power Searches with Tokens).

§ Find them all with Spotlight. Into the Spotlight box, type tag:orange (or whatever the tag name is). The results list shows you all the icons you’ve tagged that way.

The beauty of these last two methods is that you can combine search criteria. In the Spotlight box, you could search for tag:orange and kind:movie, for example.

Detagging Files

To remove a tag from an icon, use any of the same menu commands you used to apply the tag in the first place (right-click, File→Tags, click the ![]() menu). In the Tags drop-down box, just delete the tag name.

menu). In the Tags drop-down box, just delete the tag name.

The Trash

No single element of the Macintosh interface is as recognizable or famous as the Trash icon, which appears at the end of the Dock. (It’s actually a wastebasket, not a can, but let’s not quibble.)

You can discard almost any icon by dragging it into the Trash can. When the tip of your arrow cursor touches the Trash icon, the little wastebasket turns black. When you release the mouse, you’re well on your way to discarding whatever it was you dragged. As a convenience, OS X even replaces the empty-wastebasket icon with a wastebasket-filled-with-crumpled-up-papers icon, to let you know there’s something in there.

It’s worth learning the keyboard alternative to dragging something into the Trash: Highlight the icon, and then press ⌘-Delete (which corresponds to the File→Move to Trash command). This technique is not only far faster than dragging, but it also requires far less precision, especially if you have a large screen. OS X does all the Trash-targeting for you.

Rescuing Files and Folders from the Trash

File and folder icons sit in the Trash forever—or until you choose Finder→Empty Trash, whichever comes first.

If you haven’t yet emptied the Trash, you can open its window by clicking the wastebasket icon once. Now you can review its contents: icons that you’ve placed on the waiting list for extinction. If you change your mind, you can rescue any of these items in any of these ways:

§ Use the Put Back command. This feature flings the trashed item back into whatever folder it came from, even if that was weeks ago.

You’ll find the Put Back command wherever fine shortcut menus are sold. For example, it appears when you right-click or two-finger click the icon or click it and then open the ![]() menu.

menu.

TIP

The same keystroke you use to hurl something into the trash—⌘-Delete—also works to hurl it back out again. That is, you can highlight something in the Trash and press ⌘-Delete to put it back where it once belonged.

§ Hit Undo. If dragging something to the Trash was something you just did, you can press ⌘-Z—the keyboard shortcut for the Edit→Undo command. (The Finder offers a five-level Undo, meaning that you can retrace your last five actions.)

Undo not only removes a file from the Trash, but also returns it to the folder from which it came. This trick works even if the Trash window isn’t open.

§ Drag it manually. Of course, you can also drag any icon out of the Trash with the mouse, which gives you the option of putting it somewhere new (as opposed to back in the folder it started from).

Emptying the Trash I: Quick and Easy

If you’re confident that the items in the Trash window are worth deleting, use any of these three options:

§ Choose Finder→Empty Trash.

§ Press Shift-⌘-Delete. Or, if you’d just as soon not bother with the “Are you sure?” message, then throw the Option key in there, too.

§ Right-click the wastebasket icon (or Control-click it, or just click it and hold the mouse button down for a moment); choose Empty Trash from the shortcut menu.

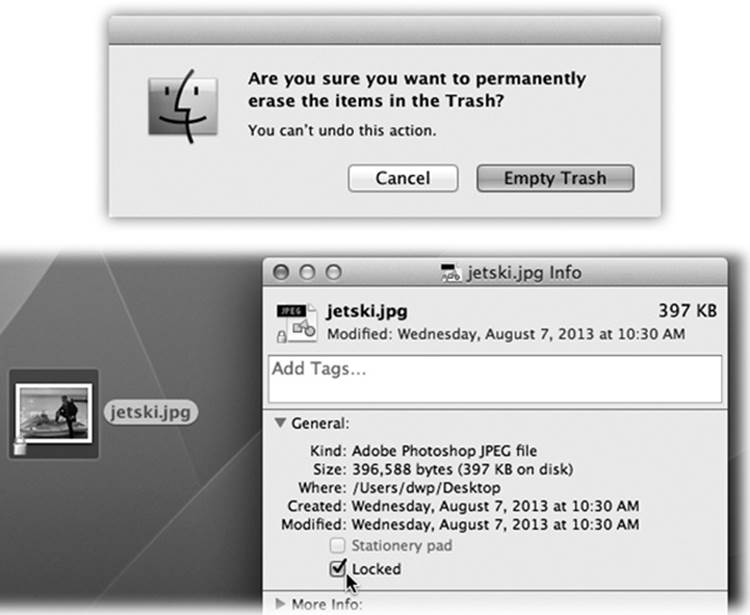

Figure 3-9. Top: Your last warning. OS X doesn’t tell you how many items are in the Trash or how much disk space they take up. Bottom: The Get Info window for a locked file. Locking a file in this way isn’t military-level security by any stretch—any passing evildoer can unlock the file in the same way. But it does trigger a warning when you try to put it into the Trash, providing at least one layer of protection against losing or deleting it.

The Mac asks you to confirm your decision. (Figure 3-9 shows this message.) If you click Empty Trash (or press Return), OS X deletes those files from your hard drive.

TIP

If you’d rather not be interrupted for confirmation every time you empty the Trash, you can suppress this message permanently. To do that, choose Finder→Preferences, click Advanced, and then turn off “Show warning before emptying the Trash.”

Emptying the Trash II: Secure and Forever

When you empty the Trash as described above, each trashed icon sure looks like it disappears. The truth is, though, the data in each file is still on the hard drive. Yes, the space occupied by the dearly departed is now marked with an internal “This space available” message, and in time, new files may overwrite that spot. But in the meantime, some future eBay buyer of your Mac—or, more imminently, a savvy family member or office mate—could use a program like Data Rescue or FileSalvage to resurrect those deleted files. (In more dire cases, companies like DriveSavers.com can use sophisticated clean-room techniques to recover crucial information—for several hundred dollars, of course.)

That notion doesn’t sit well with certain groups, like government agencies, international spies, and the paranoid. As far as they’re concerned, deleting a file should really, really delete it, irrevocably, irretrievably, and forever.

OS X’s Secure Empty Trash command to the rescue! When you choose this command from the Finder menu, the Mac doesn’t just obliterate the parking spaces around the dead file. It actually records new information over the old—random 0’s and 1’s. Pure static gibberish.

The process takes longer than the normal Empty Trash command, of course. But when it absolutely, positively has to be gone from this earth for good (and you’re absolutely, positively sure you’ll never need that file again), Secure Empty Trash is secure indeed.

GEM IN THE ROUGH: OPENING THINGS IN THE TRASH

Now and then, it’s very useful to see what some document in the Trash is before committing it to oblivion—and the only way to do that is to open it.

Trouble is, you can’t open it by double-clicking; you’ll get nothing but an error message.

Or at least that’s what Apple wants you to think.

First of all, you can use Quick Look (Quick Look) to inspect something in the Trash.

But if Quick Look can’t open the file—or if you want to edit it instead of just reading it—drag the document onto the icon of a program that can open it. That is, if a file called Don’t Read Me.txt is in the Trash, you can drag it onto, say, the Word or TextEdit icon in your Dock.

The document dutifully pops open on the screen. Inspect, close, and then empty the Trash (or rescue the document).

TIP

You can also direct the Mac to use this secure method all the time. To do that, choose Finder→Preferences, click Advanced, and turn on “Empty Trash securely.”

Locked Files

By highlighting a file or folder, choosing File→Get Info, and turning on the Locked checkbox, you protect that file or folder from accidental deletion (see Figure 3-9 at bottom). A little ![]() icon appears on the corner of the full-size icon, also shown in Figure 3-9.

icon appears on the corner of the full-size icon, also shown in Figure 3-9.

Locked files these days behave quite differently than they did in early OS X versions:

§ Dragging the file into another folder makes a copy; the original stays put.

§ Putting the icon into the Trash produces a warning message: “Item ‘Shopping List’ is locked. Do you want to move it to the Trash anyway?” If so, click Continue.

§ Once a locked file is in the Trash, you don’t get any more warnings. When you empty the Trash, that item gets erased right along with everything else.

You can unlock files easily enough. Press Option-⌘-I (or press Option as you choose File→Show Inspector). Turn off the Locked checkbox in the resulting Info window. (Yes, you can lock or unlock a mass of files at once.)

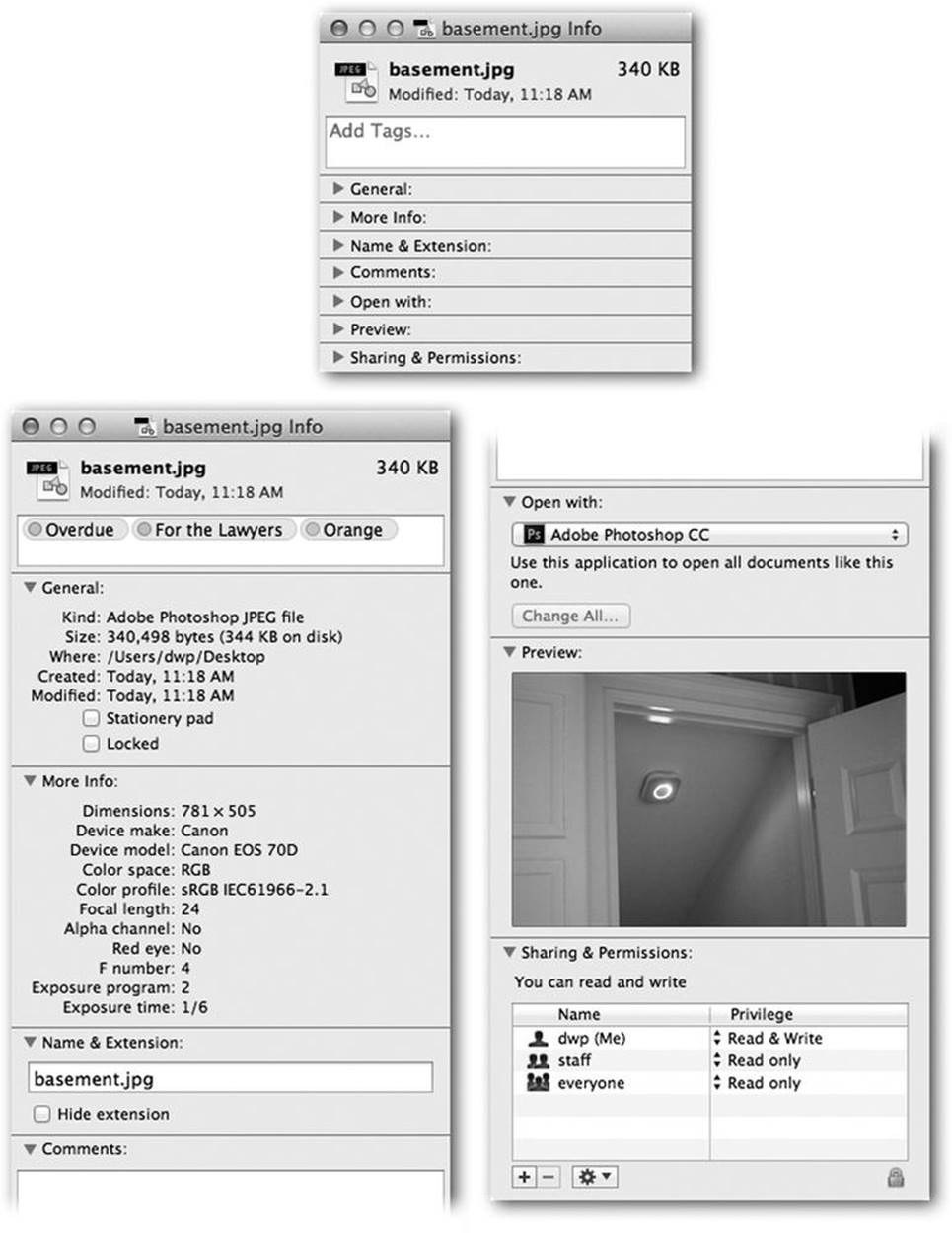

Get Info

By clicking an icon and then choosing File→Get Info, you open an important window like the one shown in Figure 3-10. It’s a collapsible, multipanel screen that provides a wealth of information about a highlighted icon.

For example:

§ For a document icon, you see when it was created and modified, and what programs it “belongs” to.

§ For an alias, you learn the location of the actual icon it refers to.

§ For a program, you see whether or not it’s been updated to run on Intel-based Macs. If so, the Get Info window says either “Kind: Intel” (requires an Intel Mac) or “Kind: Universal” (runs on Intel and older Macs). If it says “Kind: PowerPC,” then it can’t run in Mavericks.

§ For a disk icon, you get statistics about its capacity and how much of it is full.

§ If you open the Get Info window when nothing is selected, you get information about the desktop itself (or the open window), including the amount of disk space consumed by everything sitting on or in it.

§ If you highlight so many icons simultaneously that their Get Info windows would overwhelm your screen, OS X thoughtfully tallies up their information into a single summary window. It shows you how many icons you highlighted, breaks them down by type (“23 documents, 3 folders,” for example), and adds up the total of their file sizes. That’s a great opportunity to change certain file characteristics on numerous files simultaneously, such as locking or unlocking them, hiding or showing their file name suffixes, changing their ownership or permissions (Sharing Any Folder), and so on.

Figure 3-10. Top: The Get Info window can be as small as this, with all its information panes collapsed. Bottom: Or, if you click each flippy triangle to open its corresponding panel of information (or Option-click to expand or collapse them all at once), it can be as huge as this—shown here split in two because the book isn’t tall enough to show the whole thing. The resulting dialog box can easily grow taller than your screen, which is a good argument for either (a) closing the panels you don’t need at any given moment or (b) running out to buy a really gigantic monitor. And as long as you’re taking the trouble to read this caption, here’s a tasty bonus: There’s a secret command called Get Summary Info. Highlight a group of icons, press Control-⌘-I, and marvel at the special Get Info box that tallies up their sizes and other characteristics.

How many icons do you have to highlight to trigger this Multiple Item Info box? That depends on the size of your screen; bigger monitors can hold more Get Info boxes. If you highlight fewer than that magic number of icons, OS X opens up individual Get Info windows for each one.

TIP

You can force the Multiple Item Info dialog box to appear, though, even if you’ve highlighted only a couple of icons. Just press Control-⌘-I. (The Option-⌘-I trick described next works for this purpose, too.)

The Get Info Panels

Apple built the Get Info window out of a series of collapsed “flippy triangles,” as shown in Figure 3-10. Click a triangle to expand a corresponding information panel.

Depending on whether you clicked a document, program, disk, alias, or whatever, the various panels may include the following:

§ Tags. Yes, here’s yet another place where you can add or delete tags for a file.

§ Spotlight Comments. Here you can type in comments for your own reference. Later, you can view these remarks in any list view if you display the Comments column—and you can find them when you conduct Spotlight searches (The Spotlight Menu).

§ General. Here’s where you can view the name of the icon and also see its size, creation date, most recent change date, locked status, and so on.

If you click a disk, this info window shows you its capacity and how full it is. If you click the Trash, you see how much stuff is in it. If you click an alias, this panel shows you a Select New Original button and reveals where the original file is. The General panel always opens the first time you summon the Get Info window.

§ More Info. Just as the name implies, here you’ll find more info, most often the dimensions and color format (graphics only) and when the icon was last opened. These morsels are also easily Spotlight-searchable.

§ Name & Extension. On this panel, you can read and edit the name of the icon in question. The “Hide extension” checkbox refers to the suffix on OS X file names (the last three letters of Letter to Congress.doc, for example).

Many OS X documents, behind the scenes, have file name extensions of this kind—but OS X comes factory-set to hide them. By turning off this checkbox, you can make the suffix reappear for an individual file. (Conversely, if you’ve elected to have OS X show all file name suffixes, then this checkbox lets you hide the extensions on individual icons.)

UP TO SPEED: COMPRESSING, ZIPPING, AND ARCHIVING

OS X comes with a built-in command that compresses a file or folder down to a single, smaller icon—an archive—suitable for storing or emailing. It creates .zip files, the same compression format used in Windows. That means you can now send .zip files back and forth to PC owners without worrying that they won’t be able to open them.

To compress something, right-click (two-finger click) a file or folder and choose “Compress [the icon’s name]” from the shortcut menu. (Of course, you can use the File menu or ![]() menu instead.)

menu instead.)

OS X thoughtfully creates a .zip archive, but it leaves the original behind so you can continue working with it.

Opening a .zip file somebody sends you is equally easy: Just double-click it. Zip!—it opens.

§ Open with. This section is available for documents only. Use the controls on this screen to specify which program will open when you double-click this document, or any document of its type.

§ Preview. When you’re examining pictures, text files, PDF files, Microsoft Office files, sounds, clippings, and movies, you see a magnified thumbnail version of what’s actually in that document. This preview is like a tiny version of Quick Look (Chapter 2). A controller lets you play sounds and movies where appropriate.

§ Sharing & Permissions. This panel is available for all kinds of icons. If other people have access to your Mac (either from across the network or when logging in, in person), this panel lets you specify who is allowed to open or change this particular icon. See Chapter 15 for a complete discussion of this hairy topic.

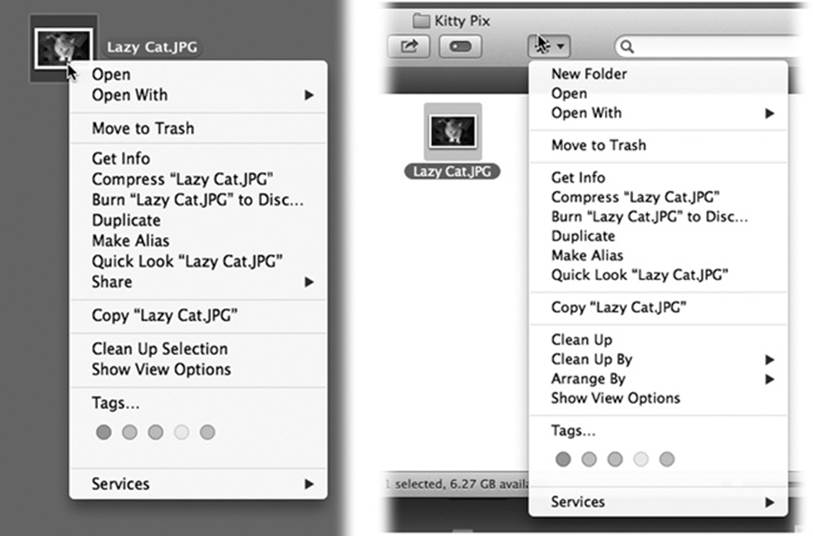

Shortcut Menus, Action Menus

It’s part of the Mac’s user-friendly heritage: You can do practically everything using only the mouse. Everything is out front, unhidden, and clickable, whether it’s an icon, button, or menu.

But as in Windows, you can shave seconds and steps off your workload if you master shortcut menus: short menus that sprout out of things you click, offering commands that the software thinks you might want to invoke at the moment (Figure 3-11).

Figure 3-11. These pop-up entities used to be called contextual menus, but Apple started calling them “shortcut menus” a few years ago, perhaps because that’s what they’re called in Windows and Unix.

To summon one, just right-click or two-finger click something—an icon, the desktop, a window, a link in Safari, text in a word processor, whatever. You can also trigger these shortcut menus with special clicks on your trackpad or Magic Mouse; see What to Do with Search Results for additional options.

In any case, a menu drops down listing relevant commands: Get Info, Move to Trash, Copy, and so on. You can click the command you want, or type the first couple of letters of it and then tap the space bar.

These menus become more useful the more you get to know them. The trouble is, millions of Mac fans never even knew they existed.

That’s why there’s a second way to access them. At the top of every Finder window, you’ll find a ![]() pop-up menu that’s technically called the Action menu (shown in Figure 3-11).

pop-up menu that’s technically called the Action menu (shown in Figure 3-11).

It lists the same sorts of commands you’d find in the shortcut menus, but it’s visible, so novices stand a better chance of stumbling onto it.

The Finder shortcut menus offer some of the most useful Mac features ever. Don’t miss these two in particular:

New Folder with Selection

Imagine this: You’ve got a bunch of scattered icons on your desktop, or a mass of related files in a window. You can now highlight all of them; right-click or two-finger click any one of them; and from the shortcut menu, choose “New Folder with Selection (12 items)” (or whatever the number of icons is).

With a cool animation, the Finder visibly throws the selected icons into a brand-new folder. It’s initially named New Folder With Items (duh), but the hard part is over. All you have to do is rename it—and be grateful that you were spared the 736 steps it would have taken you to do the same job manually.

Share ![]()

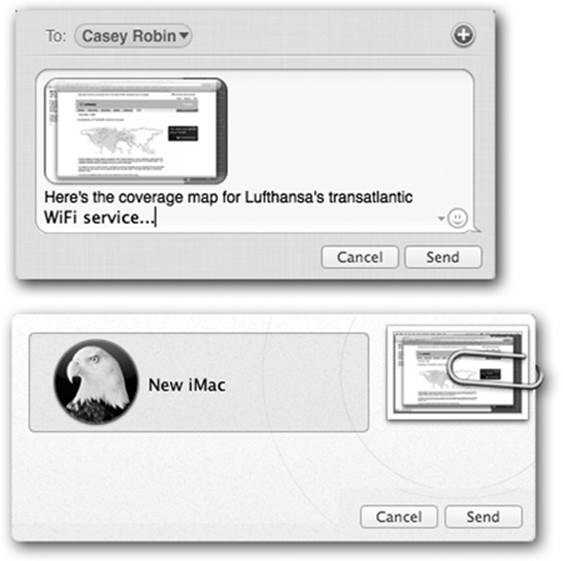

Here’s a handy menu of ways to send whatever’s highlighted to somebody else. In the case of selected Finder icons, you can use these three methods (see Figure 3-12):

§ Email whips open Mail and creates a new, outgoing message with the selected file(s) already attached. Address and send, and make a sacrifice to the right-clicky gods.

§ Message sends the file to somebody’s iPhone. Type a little message and then click Send. Off it goes, just as though you’d sent it from the Messages app (Chapter 13).

§ AirDrop. AirDrop is a slick, simple way to shoot a file from one Mac to another without involving any setup, network settings, or user accounts. Click the file(s) you want to send, click Share→AirDrop, click the name of the nearby destination Mac, and click Send. Off it goes!

This menu may also offer to send your file to Twitter, Facebook, or (if it’s a photo or video (Flickr or Vimeo). For details on these and other Share-menu options, see The Share Button.

Figure 3-12. The Share menu in every Finder window offers direct access to three ways of transmitting a selected file icon to somebody else. Top: For example, you can send a file to somebody’s cellphone or iMessage account. Just specify the lucky winner’s name here—and add a smiley face, if the mood strikes you (use the pop-up menu in the lower right). Bottom: Alternatively, you can send a file to a nearby Mac (running Lion or later) without having to fiddle with network or sharing settings. Just type the name of the Mac you want and then click Send.

The Spotlight Menu

Every computer offers a way to find files. And every system offers several different ways to open them. But Spotlight, a star feature of OS X, combines these two functions in a fast, efficient way.

See the little magnifying-glass icon (![]() ) in your menu bar? That’s the mouse-driven way to open the Spotlight search box.

) in your menu bar? That’s the mouse-driven way to open the Spotlight search box.

The other way is to press ⌘-space bar. If you can memorize only one keystroke on your Mac, that’s the one to learn. It works both at the desktop and in other programs.

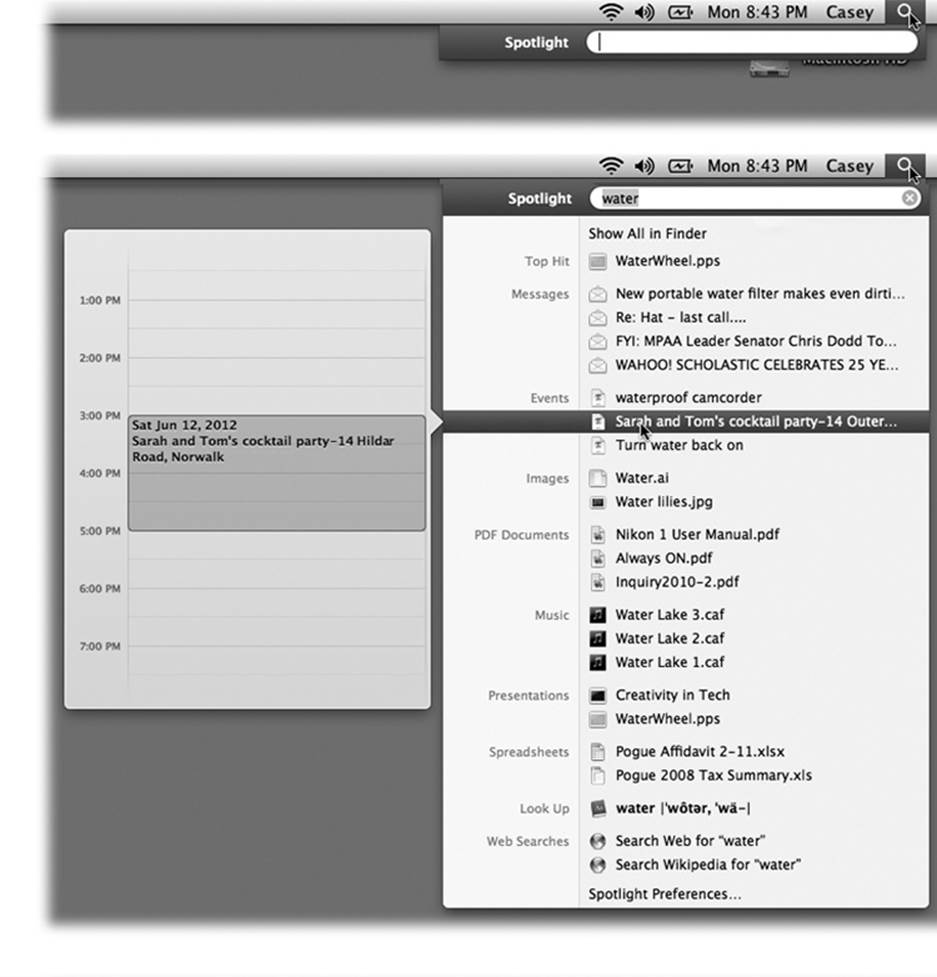

In any case, the Spotlight text box appears just below your menu bar (Figure 3-13).

Begin typing to identify what you want to find and open. For example, if you’re trying to find a file called Pokémon Fantasy League.doc, typing just pok or leag would probably suffice. (The search box doesn’t find text in the middles of words, though; it searches from the beginnings of words.)

A menu immediately appears below the search box, listing everything Spotlight can find containing what you’ve typed so far. (This is a live, interactive search; that is, Spotlight modifies the menu of search results as you type.) The menu lists every file, folder, program, email message, Contacts entry, calendar appointment, picture, movie, PDF document, music file, Web bookmark, Microsoft Office document (Word, PowerPoint, Excel, Entourage), System Preferences panel, To Do item, chat transcript, Web site in your History list, and even font that contains what you typed, regardless of its name or folder location.

NOTE

Spotlight also finds things according to their file types (type .doc to find Word files), download source (type cnet.com to find programs you downloaded from that site), sender (a name or email address), and Finder tag.

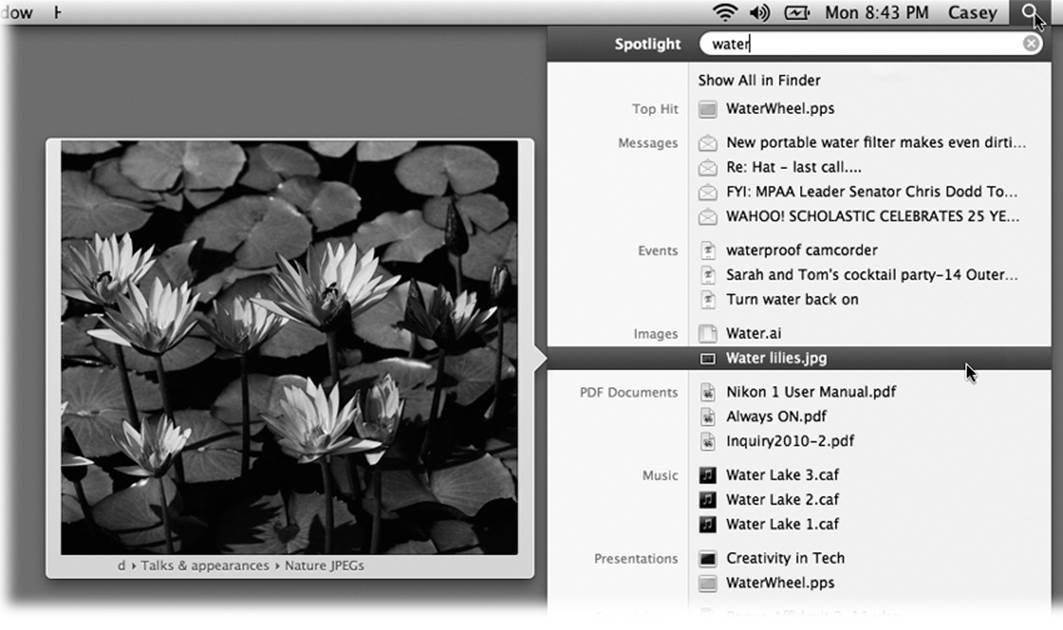

Figure 3-13. Top: Press ⌘-space bar, or click the magnifying-glass icon, to make the search box appear. Bottom: As you type, Spotlight builds the list of every match it can find, neatly organized by type: programs, documents, folders, images, PDF documents, and so on. But don’t miss what may be one of the most useful tweaks ever: If you’re not sure what something is, point to it without clicking—or pause on it as you walk down the list with the arrow keys. A Quick Look preview pops out to the left. It shows exactly what’s in that movie, picture, document, or whatever. If your search has found an appointment from your calendar, you actually see a slice of that day’s calendar, showing the appointment in context!

If you see the icon you were hoping to dig up, just click it to open it. Or use the arrow keys to walk down the menu, and then press Return to open the one you want.

You can use the Quick Look preview to see what something is before you take the time to open it, as shown in Figure 3-13. Or check out Figure 3-14 to see how to find out where something is.

If you click an application, it opens. If you select a System Preferences panel, System Preferences opens and presents that panel. If you choose an appointment, the Calendar program opens, already set to the appropriate day and time. Selecting an email message opens that message in Mail or Outlook. And so on.

Spotlight is so fast, it eliminates a lot of the folders-in-folders business that’s a side effect of modern computing. Why burrow around in folders when you can open any file or program with a couple of keystrokes?

TIP

You can drag icons right out of the results list. For example, you can drag one onto the Desktop to park it there, into a window or a folder to move it, into the Trash to delete it, onto the AirDrop icon (in the Sidebar) to hand it over to a colleague, to another disk icon to back it up, and so on.

Figure 3-14. If you press ⌘-Option as you point to one of the results, you get a line of text beneath the image that identifies the file’s location.

Spotlight-Menu Tips

It should be no surprise that a feature as important as Spotlight comes loaded with options, tips, and tricks. Here it is—the official, unexpurgated Spotlight Tip-O-Rama:

§ If the very first item—labeled Top Hit—is the icon you were looking for, just press Return to open it. This is a huge deal, because it means that in most cases, you can perform the entire operation without ever taking your hands off the keyboard.

To open Safari in a hurry, for example, press ⌘-space bar (to open the Spotlight search box), type safa, and hit Return, all in rapid-fire sequence, without even looking. Presto: Safari is before you.

And what, exactly, is the Top Hit? OS X chooses it based on its relevance (the importance of your search term inside that item) and timeliness (when you last opened it).

TIP

Spotlight makes a spectacular application launcher. That’s because Job One for Spotlight is to display the names of matching programs in the results menu. Their names appear in the list nearly instantly—long before Spotlight has built the rest of the menu of search results.

If some program on your hard drive doesn’t have a Dock icon, for example—or even if it does—there’s no faster way to open it than to use Spotlight.

§ To jump to (highlight) a search result’s Finder icon instead of opening it, ⌘-click its name. Or arrow-key your way to the result’s name and then press ⌘-Return.

Spotlight’s menu shows you only 20 of the most likely suspects, evenly divided among the categories (Documents, Applications, and so on). The downside: To see the complete list, you have to open the Spotlight window (The Spotlight Window).

The upside: It’s fairly easy to open something in this menu from the keyboard. Just press ⌘-![]() (or ⌘-

(or ⌘-![]() ) to jump from category to category. Once you’ve highlighted the first result in a category, you can walk through the remaining four by pressing the arrow key by itself. Then, once you’ve highlighted what you want, press Return to open it.

) to jump from category to category. Once you’ve highlighted the first result in a category, you can walk through the remaining four by pressing the arrow key by itself. Then, once you’ve highlighted what you want, press Return to open it.

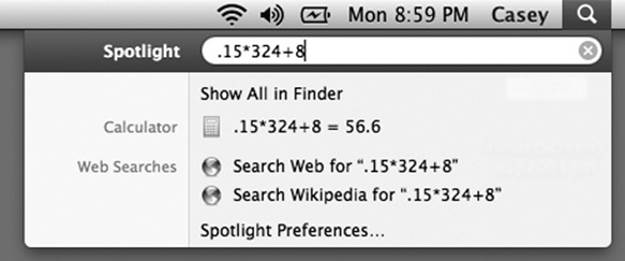

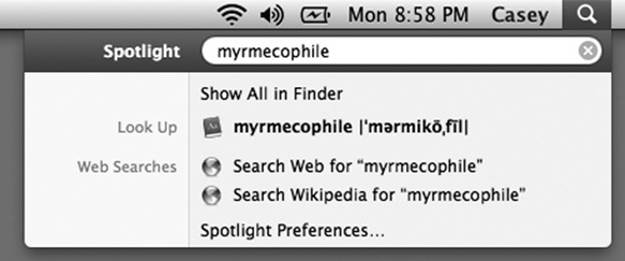

GEM IN THE ROUGH: SWEET SPOTLIGHT SERENDIPITY: EQUATIONS AND DEFINITIONS

Spotlight has two secret features that turn it into a different beast altogether.

First, it’s a tiny pocket calculator, always at the ready. Click in the search box (or press ⌘-space bar), type or paste 38*48.2-7+55, and marvel at the first result in the Spotlight menu: 1879.6. There’s your answer—and you didn’t even have to fire up the Calculator.

(For shorter equations—only a few characters long—the first result in the Spotlight menu shows the entire equation, like .15*234=35.1.)

And it’s not just a four-function calculator, either. It works with square roots: Type sqrt(25), and you’ll get the answer 5. It also works with powers: Type pow(6,6)—that is, 6 to the power of 6—and you’ll get 46656. You can even type pi to represent, you know, pi.

You can copy the result to the Clipboard, or even drag it out of the Spotlight bar into another program.

For a complete list of math functions in Spotlight, open Terminal (see Saving a report), type man math, and press Return.

Second, the Spotlight menu is now a full-blown English dictionary. Or, more specifically, it’s wired directly into OS X’s own dictionary, which sits in your Applications folder.

So if you type a word—say, myrmecophile—into the search box, you’ll see the Dictionary definition near the bottom of the results. Point to it without clicking to read the full-blown entry, thanks to the pop-out Quick Look preview. (In this example, that would be: “n: an invertebrate or plant that has a symbiotic relationship with ants.”)

In other words, you can get to anything in the Spotlight menu with only a few keystrokes.

§ The Esc key (top-left corner of your keyboard) offers a two-stage “back out of this” method. Tap it once to close the Spotlight menu and erase what you’ve typed, so that you’re all ready to type in something different. Tap Esc a second time to close the Spotlight text box entirely, having given up on the whole idea of searching.

§ Think of Spotlight as your little black book. When you need to look up a number in Contacts, don’t bother opening Contacts; it’s faster to use Spotlight. You can type somebody’s name or even part of someone’s phone number.

§ If you’re searching for just one word, you’ll see a “Look Up” category near the bottom of the results menu. Click it to open up that word’s definition in the Dictionary program.

§ The bottom of Spotlight always lists commands for “Search Web for [your phrase]” and “Search Wikipedia for [your phrase].” They take you straight to the Google search or the Wikipedia (online encyclopedia) results for whatever you typed.

§ Among a million other things, Spotlight tracks the keywords, descriptions, faces, and places you’ve applied to your pictures in iPhoto. As a result, you can find, open, or insert any iPhoto photo at any time, no matter what program you’re using, just by using the Spotlight box at the top of every Open File dialog box! This is a great way to insert a photo into an outgoing email message, a presentation, or a Web page you’re designing. iPhoto doesn’t even have to be running.

§ Spotlight is also a quick way to adjust one of your Mac’s preference settings. Instead of opening the System Preferences program, type the first few letters of, say, volume or network or clock into Spotlight. The Spotlight menu lists the appropriate System Preferences panel, so you can jump directly to it.

§ As shown in Figure 3-14, you get a preview of what’s inside a file listed in the Spotlight menu when you point to it without clicking. But if you add the ⌘ key, you see a tiny line of text below the preview. It tells you the item’s actual name—which is useful if Spotlight listed something because of text that appears inside the file, not its name—and if you wait a moment, you also see its folder path (that is, where it is on your hard drive).

TIP

If you’re in a hurry, just press ⌘-Option as you point. That makes the folder path appear immediately.

§ While you’re pointing to something in the results list, you can press ⌘-I to open the Get Info window for it.

§ The Spotlight menu lists 20 found items. In the following pages, you’ll learn about how to see the rest of the stuff. But for now, note that you can eliminate some of the categories that show up here (like PDF documents or Bookmarks), and even rearrange them, to permit more of the otherkinds of things to enjoy those 20 seats of honor. Details on Customizing Spotlight.

§ Spotlight shows you only the matches from your account and the public areas of the Mac (like the System, Application, and Developer folders)—but not what’s in anyone else’s Home folder. If you were hoping to search your spouse’s email for phrases like “meet you at midnight,” forget it.

§ If Spotlight finds a different version of something on each of two hard drives, it lets you know by displaying a faint gray hard drive name after each such item in the menu.

§ Spotlight works by storing an index, a private, multimegabyte Dewey Decimal System, on each hard drive, disk partition, or USB flash (memory) drive. If you have some oddball type of disk, like a hard drive that’s been formatted for Windows, Spotlight doesn’t ordinarily index it—but you can turn on indexing by using the File→Get Info command on that drive’s icon.

TIP

Spotlight can even find words inside files on other computers on your network—as long as they’re also Macs running Mac OS X Leopard (10.5) or later. If not, Spotlight can search only for the names of files on other networked computers.

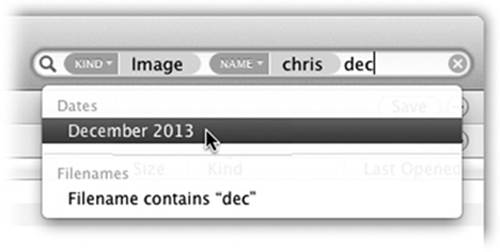

Advanced Menu Searches

Most people just type the words they’re looking for into the Spotlight box. But if that’s all you type, you’re missing a lot of the fun.

Use quotes

If you type more than one word, Spotlight works just the way Google does. That is, it finds things that contain both words somewhere inside.

But if you’re searching for a phrase where the words really belong together, put quotes around them. You’ll save yourself from having to wade through hundreds of results where the words appear separately.

For example, searching for military intelligence rounds up documents that contain those two words, but not necessarily side by side. Searching for “military intelligence” finds documents that contain that exact phrase. (Insert your own political joke here.)

Limit by kind

You can confine your search to certain categories using a simple code. For example, to find all photos, type kind:image. If you’re looking for a presentation document but you’re not sure whether you used Keynote, iWork, or PowerPoint to create it, type kind:presentation into the box. And so on.

Here’s the complete list of kinds. Remember to precede each keyword type with kind and a colon.

|

To find this: |

Use one of these keywords: |

|

A program |

app, application, applications |

|

Someone in your address book |

contact, contacts |

|

A folder or disk |

folder, folders |

|

A message in Mail |

email, emails, mail message, mail messages |

|

A Calendar appointment |

event, events |

|

A Calendar task |

to do, to dos, todo, todos |

|

A graphic |

image, images |

|

A movie |

movie, movies |

|

A music file |

music |

|

An audio file |

audio |

|

A PDF file |

pdf, pdfs |

|

A System Preferences control |

preferences, system preferences |

|

A Safari bookmark |

bookmark, bookmarks |

|

A font |

font, fonts |

|

A presentation (PowerPoint, iWork) |

presentation, presentations |

You can combine these codes with the text you’re seeking, too. For example, if you’re pretty sure you had a photo called “Naked Mole-Rat,” you could cut directly to it by typing mole kind:images or kind:images mole (the order doesn’t matter).

Limit by recent date

You can use a similar code to restrict the search by chronology. If you type date:yesterday, then Spotlight limits its hunt to items you last opened yesterday.

Here’s the complete list of date keywords you can use: this year, this month, this week, yesterday, today, tomorrow, next week, next month, next year. (The last four items are useful only for finding upcoming Calendar appointments. Even Spotlight can’t show you files you haven’t created yet.)

Limit by metadata

If your brain is already on the verge of exploding, now might be a good time to take a break.

You can limit Spotlight searches by any of the 125 different info-morsels that may be stored as part of the files on your Mac: author, audio bit rate, city, composer, camera model, pixel width, and so on. Other has a complete discussion of these so-called metadata types. (Metadata means “data about the data”—that is, descriptive info-bites about the files themselves.) Here are a few examples:

§ author:casey. Finds all documents with “casey” in the Author field. (This presumes that you’ve actually entered the name Casey into the document’s Author box. Microsoft Word, for example, has a place to store this information.)

§ width:800. Finds all graphics that are 800 pixels wide.

§ flash:1. Finds all photos that were taken with the camera’s flash on. (To find photos with the flash off, you’d type flash:0. A number of the yes/no criteria work this way: Use 1 for yes, 0 for no.)

§ modified:3/7/14-3/10/14. Finds all documents modified between March 7 and March 10, 2014. You can also type created:6/1/14 to find all the files you created on June 1, 2014. Type modified:<=3/9/14 to find all documents you edited on or before March 9, 2014.

As you can see, three range-finding symbols are available for your queries: <, >, and - (hyphen). The < means “before” or “less than”; the > means “after” or “greater than”; and the hyphen indicates a range (of dates, sizes, or whatever you’re looking for).

TIP

Here again, you can string words together. To find all PDFs you opened today, use date:today kind:PDF. And if you’re looking for a PDF document that you created on July 4, 2012, containing the word wombat, you can type created:7/4/12 kind:pdf wombat—although at this point, you’re not saving all that much time.

The Spotlight Window

As you may have noticed, the Spotlight menu doesn’t list every match on your hard drive. Unless you own one of those extremely rare 60-inch Apple Skyscraper Displays, there just isn’t room.

Instead, Spotlight uses some fancy behind-the-scenes analysis to calculate and display the 20 most likely matches for what you typed. But at the top of the menu, you usually see that there are many other possible matches; it says, “Show All in Finder,” meaning that there are other candidates.

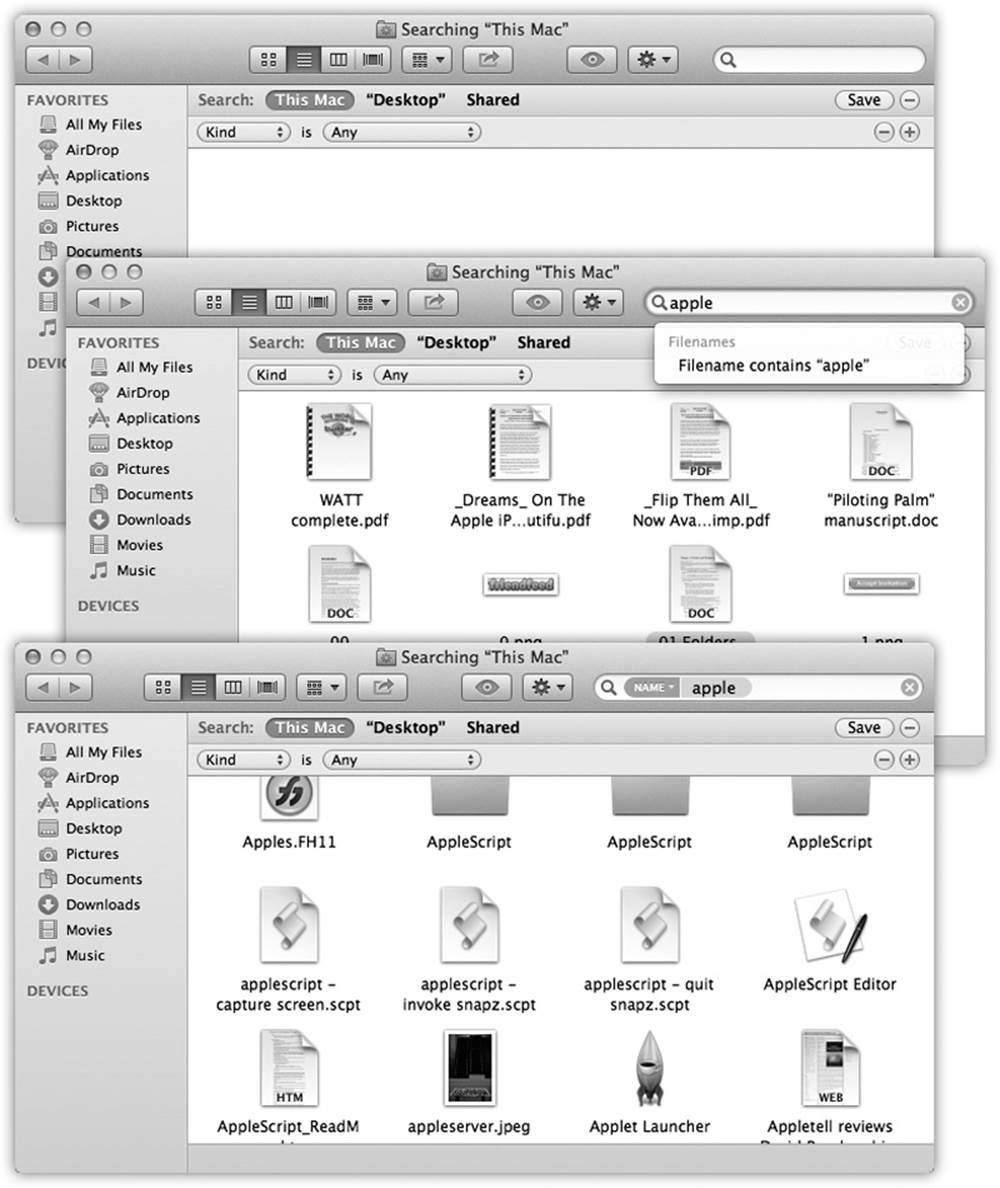

There is, however, a second, more powerful way into the Spotlight labyrinth. And that’s to use the Spotlight window, shown in Figure 3-15.

You can open the Spotlight window in either of two ways:

From Spotlight Menu

If the Spotlight menu—its Most Likely to Succeed list—doesn’t include what you’re looking for, then click Show All in Finder. You’ve just opened the Spotlight window.

Now you have access to the complete list of matches, neatly listed in what appears to be a standard Finder window.

From the Finder

When you’re in the Finder, you can also open the Spotlight window directly, without using the Spotlight menu as a trigger. Actually, there are three ways to get there:

§ ⌘-F (for Find, get it?). When you choose File→Find (⌘-F), you get an empty Spotlight window, ready to fill in for your search (Figure 3-15, top).

TIP

When the Find window opens, what folder does it intend to search?

That’s up to you. Choose Finder→Preferences→Advanced. From the “When performing a search” pop-up menu, you can choose Search This Mac, Search the Current Folder (usually what you want), or Use the Previous Search Scope (that is, either “the whole Mac” or “the current folder,” whichever you set up last time).

Figure 3-15. Top: The Spotlight window stands ready to search the currently open window. Middle: When you begin to type your search term, OS X presents a pop-up menu of suggestions. For example, when you type apple, it’s asking: “Would you like me to limit the search results to files with the word ‘apple’ in their names?” If you ignore the suggestions, the window shows you all matches—including files with the word “apple” inside them. Bottom: But if you click one of those suggestions—“Filename contains ‘apple,’ ” in this case—the results window changes. Now you’re seeing only icons that contain the word “apple.”

§ Option-⌘-space bar. This keystroke opens the same window. But it always comes set to search everything on your Mac (except other people’s Home folders, of course), regardless of the setting you made in Preferences (as described in the Tip above).

§ Open any desktop window, and type something into the search box at upper right. Presto—the mild-mannered folder window turns into the Spotlight window, complete with search results.

TIP

You can change the Find keystrokes to just about anything you like. See Privacy Settings.

The Basic Search

When the Searching window opens, you can start typing whatever you’re looking for into the search box at the top.

As you type, the window fills with a list of the files and folders whose names contain what you typed. It’s just like the Spotlight menu, but without the 20-item limit (Figure 3-15, middle).

Where to look

The three phrases at the top of the window—This Mac, [Folder Name], and Shared—are buttons. Click one to tell Spotlight where to search:

§ This Mac means your entire computer, including secondary disks attached to it (or installed inside)—minus other people’s files, of course.

§ “Letters to Congress” (or whatever the current window is) limits the search to whatever window was open. So if you want to search your Pictures folder, open it first and then hit ⌘-F. You’ll see the “Pictures” button at the top of the window, and you can click it to restrict the search to that folder.

§ Shared. Click this button to expand the search to your entire network and all the computers on it. (This assumes, of course, that you’ve brought their icons to your screen as described in Chapter 15.)

If the other computers are Macs running Leopard (Mac OS X 10.5) or later, Spotlight can search their files just the way it does on your own Mac—finding words inside the files, for example. If they’re any other kind of computer, Spotlight can search for files only by name.

TIP

If the object of your quest doesn’t show up, you can adjust the scope of the search with one quick click on another button at the top of the window, like This Mac or Shared. Spotlight updates the results list.

Then again, if you always prefer one of those options, don’t forget that you can save yourself a click by choosing it to be the new factory setting. Specify your favorite “where to look” option by visiting Finder→Preferences→Advanced and using the “When performing a search” pop-up menu. Your choices are Search This Mac, Search the Current Folder, or Use the Previous Search Scope (that is, “whatever I chose last time”).

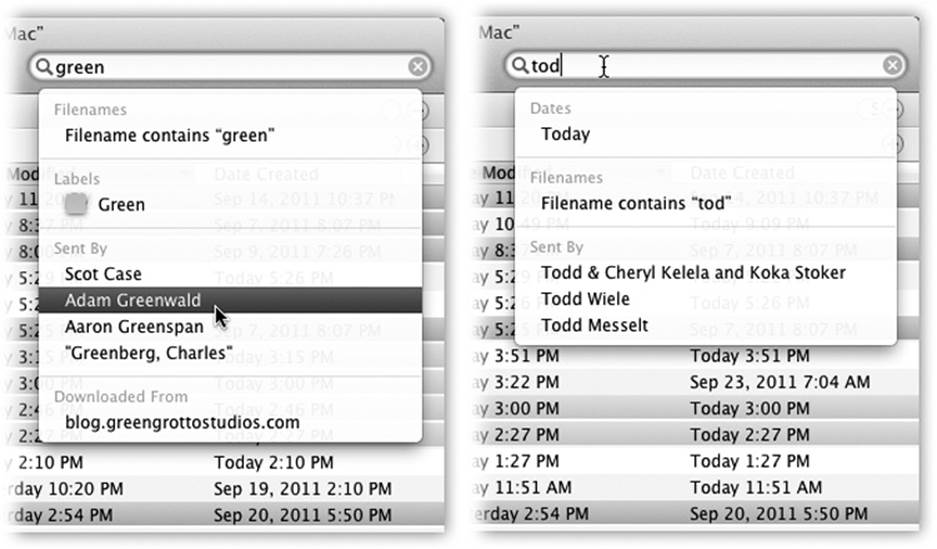

The suggestions list

The Find window used to offer two other important buttons at the top: Contents, meaning, “Search for the words inside your files, along with all the metadata attached to them,” and File Name, for when it’s faster to search for characters in the file’s name, just as people did before Spotlight came along.

These days, though, OS X tries to figure out what you’re looking for—file names or words inside files. It may show you both in the same results list.

But more important, it offers a suggestions pop-up menu, shown in Figure 3-16. Its purpose is to help you narrow down the results list with one quick click. Whatever you click here is instantly immortalized as a search token, described below.

Figure 3-16. If you find these suggestions helpful, click one (or press the ![]() key to walk down the list, and then press Enter to select the one you want). If you’re fine with the search results as they’ve already popped up—no further refining necessary—tap the Esc key to close the drop-down list.

key to walk down the list, and then press Enter to select the one you want). If you’re fine with the search results as they’ve already popped up—no further refining necessary—tap the Esc key to close the drop-down list.

You may see any of these headings in the suggestions list:

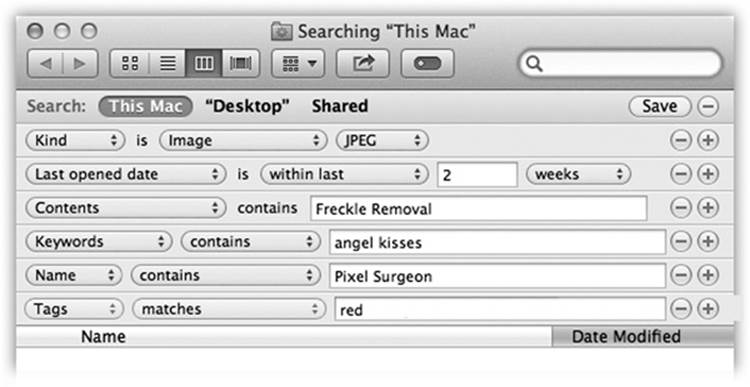

§ Filenames. The top option is always “Filenames”; click it to search by the files’ names only. If you type chris into the box, you want files whose names contain that word.