How Google Works

Culture—Believe Your Own Slogans

One Friday afternoon in May 2002, Larry Page was playing around on the Google site, typing in search terms and seeing what sort of results and ads he’d get back. He wasn’t happy with what he saw. He would enter a query for one thing, and while Google came back with plenty of relevant organic results, some of the ads were completely unrelated to the search.22 A search for something like “Kawasaki H1B” would yield lots of ads for lawyers offering to help immigrants get H-1B US visas, but none related to the vintage motorcycle to which the search query referred. Or a search for “french cave paintings” delivered ads that said “buy french cave paintings at…,” with the name of an online retailer that obviously did not stock French cave paintings (or even facsimiles of them). Larry was horrified that the AdWords engine, which figured out which ads worked best with which queries, was occasionally subjecting our users to such useless messages.

At that point, Eric still thought Google was a fairly normal start-up. But what happened over the next seventy-two hours completely shifted that perception. In a normal company, the CEO, seeing a bad product, would call the person in charge of the product. There would be a meeting or two or three to discuss the problem, review potential solutions, and decide on a course of action. A plan would come together to implement the solution. Then, after a fair amount of quality assurance testing, the solution would launch. In a normal company, this would take several weeks. This isn’t what Larry did.

Instead, he printed out the pages containing the results he didn’t like, highlighted the offending ads, posted them on a bulletin board on the wall of the kitchen by the pool table, and wrote THESE ADS SUCK in big letters across the top. Then he went home. He didn’t call or email anyone. He didn’t schedule an emergency meeting. He didn’t mention the issue to either of us.

At 5:05 a.m. the following Monday, one of our search engineers, Jeff Dean, sent out an email. He and a few colleagues (including Georges Harik, Ben Gomes, Noam Shazeer, and Olcan Sercinoglu) had seen Larry’s note on the wall and agreed with Larry’s assessment of the ads’ relative suckiness. But the email didn’t just concur with the founder and add some facile bromide about looking into the problem. Rather, it included a detailed analysis of why the problem was occurring, described a solution, included a link to a prototype implementation of the solution the five had coded over the weekend, and provided sample results that demonstrated how the new prototype was an improvement over the then-current system. While the details of the solution were geeky and complex (our favorite phrase from the note: “query snippet term vector”), the gist of it was that we would compute an “ad relevance score” that would assess the quality of the ad relevant to the query, and then determine whether and where the ad would be placed on the page based on that score. This core insight—that ads should be placed based on their relevancy, not just how much the advertiser was willing to pay and the number of clicks they received—became the foundation upon which Google’s AdWords engine, and a multibillion-dollar business, was built.

And the kicker? Jeff and team weren’t even on the ads team. They had just been in the office that Friday afternoon, seen Larry’s note, and understood that when your mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful, then having ads (which are information) that suck (which isn’t useful) is a problem. So they decided to fix it. Over the weekend.

The reason a bunch of employees who had no direct responsibility for ads, or culpability when they were lousy, spent their weekends transforming someone else’s problem into a profitable solution speaks to the power of culture. Jeff and gang had a clear understanding of their company’s priorities, and knew they had the freedom to try to solve any big problem that stood in the way of success. If they had failed, no one would have chastised them in any way, and when they succeeded, no one—even on the ads team—was jealous of their progress. But it wasn’t Google’s culture that turned those five engineers into problem-solving ninjas who changed the course of the company over the weekend. Rather it was the culture that attracted the ninjas to the company in the first place.

Many people, when considering a job, are primarily concerned with their role and responsibilities, the company’s track record, the industry, and compensation. Further down on that list, probably somewhere between “length of commute” and “quality of coffee in the kitchen,” comes culture. Smart creatives, though, place culture at the top of the list. To be effective, they need to care about the place they work. This is why, when starting a new company or initiative, culture is the most important thing to consider.

Most companies’ culture just happens; no one plans it. That can work, but it means leaving a critical component of your success to chance. Elsewhere in this book we preach the value of experimentation and the virtues of failure, but culture is perhaps the one important aspect of a company where failed experiments hurt. Once established, company culture is very difficult to change, because early on in a company’s life a self-selection tendency sets in. People who believe in the same things the company does will be drawn to work there, while people who don’t, won’t.23 If a company believes in a culture where everyone gets a say and decisions are made by committee, it will attract like-minded employees. But if that company tries to adopt a more autocratic or combative approach, it will have a very hard time getting employees to go along with it. Change like that not only goes against what the company stands for, it goes against its employees’ personal beliefs. That’s a tough road.

The smart approach is to ponder and define what sort of culture you want at the outset of your company’s life. And the best way to do that is to ask the smart creatives who form your core team, the ones who know the gospel and believe in it as much as you do. Culture stems from founders, but it is best reflected in the trusted team the founders form to launch their venture. So ask that team: What do we care about? What do we believe? Who do we want to be? How do we want our company to act and make decisions? Then write down their responses. They will, in all likelihood, encompass the founders’ values, but embellish them with insights from the team’s different perspectives and experiences.

Most companies neglect this. They become successful, and then decide they need to document their culture. The job falls to someone in the human resources or PR department who probably wasn’t a member of the founding team but who is expected to draft a mission statement that captures the essence of the place. The result is usually a set of corporate sayings that are full of “delighted” customers, “maximized” shareholder value, and “innovative” employees. The difference, though, between successful companies and unsuccessful ones is whether employees believe the words.

Here’s a little thought experiment for you: Think about someplace where you’ve worked. Now, try to recite its mission statement. Can you do it? If so, do you believe in it? Does it strike you as authentic, something that honestly reflects the actions and culture of the company and its employees? Or does it seem like something a group of marketing and communications people conjured up one night with a six-pack and a thesaurus? Something like: “Our mission is to build unrivaled partnerships with and value for our clients, through the knowledge, creativity, and dedication of our people, leading to superior results for our shareholders.”24 Boy, that sure checks all the boxes, doesn’t it? Clients—check; employees—check; shareholders—check. Lehman Brothers was the owner of that mission statement—at least until its bankruptcy in 2008. Surely Lehman stood for something, but you couldn’t tell from those words.

In contrast to Lehman Brothers’ leaders, David Packard, a founding member of our all-time Smart Creative Hall of Fame, took culture seriously. He noted in a 1960 speech to his managers that companies exist to “do something worthwhile—they make a contribution to society.… You can look around and still see people who are interested in money and nothing else, but the underlying drives come largely from a desire to do something else—to make a product, to give a service, generally to do something which is of value.”25

People’s BS detectors are finely tuned when it comes to corporate-speak; they can tell when you don’t mean it. So when you put your mission into writing, it had better be authentic. A good litmus test is to ask what would happen if you changed the statements that describe culture. Take “Respect, Integrity, Communication and Excellence,” which was Enron’s motto. If execs at Enron had decided to replace those concepts with something different—perhaps Greed, Greed, Lust for Money, and Greed—it might have drawn a few chuckles but otherwise there would have been no impact. On the other hand, one of Google’s stated values has always been to “Focus on the User.” If we changed that, perhaps by putting the needs of advertisers or publishing partners first, our inboxes would be flooded, and outraged engineers would take over the weekly, company-wide TGIF meeting (which is hosted by Larry and Sergey, and where employees are welcome to—and often do—voice their disagreement with company decisions). Employees always have a choice, so belie your values at your own risk.

Think about your culture, either what you want it to be or what it already is. Imagine, months or years from now, an employee working late, unable to make up his mind about a tough decision.26 He walks to the kitchen for a cup of coffee, and thinks back on the cultural values he heard expressed at company meetings, talked about with colleagues over lunch, saw demonstrated by that company veteran whom everyone respects. For this employee—for all employees—those values should clearly and plainly outline the things that matter most to the company, the things you care about. Otherwise they are meaningless, and won’t be worth a damn when it comes to helping that smart creative make the right call. What values would you want that bleary-eyed employee to consider? Write them down in a simple, concise way. Then share them, not in posters and guides, but through constant, authentic communications. As former General Electric CEO Jack Welch said in Winning: “No vision is worth the paper it’s printed on unless it is communicated constantly and reinforced with rewards.”27

When Google went public in 2004, Sergey and Larry recognized the IPO as the perfect opportunity to codify the values that would guide the company’s actions and decisions. And not just the most important actions and decisions and not just management’s actions and decisions, buteveryone’s actions and decisions, big and small, every day. These values had guided how the company had run since its founding six years earlier, and were deeply grounded in the founders’ personal experiences. Inspired by the annual letter Warren Buffett writes to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, they drafted a “letter from the founders” to include in the IPO prospectus.

The Securities and Exchange Commission initially ruled that the letter did not contain information that would be relevant to investors, and so didn’t belong in the company’s investment prospectus. We argued and eventually won the right to include it. Still, some of the statements in the letter gave the lawyers and bankers heartburn, and at one point Jonathan found himself in a conference room facing a battalion of them picking at this point or that. He steadfastly defended the text of the letter, using two main arguments: (1) Larry and Sergey had written the letter themselves, with input only from a small group of Googlers, and wouldn’t change a thing (it’s easy to hold the line in a negotiation when you are, in fact, completely unable to get your side to budge!), and (2) everything the letter said was heartfelt and true.

When it was published in April 2004, the letter generated a lot of curiosity and some criticism. What most people didn’t understand, though, was exactly why the company’s founders had spent so much time getting the letter exactly right (and why Jonathan dug his heels in every time one of the bankers or lawyers tried to change something). The letter was not primarily about Dutch auctions, voting rights, or showing off a blatant disregard for everything Wall Street. In fact, if we Wall Street have offended, think but this, and all is mended:28 The founders didn’t care about maximizing the short-term value and marketability of their stock, because they knew that recording the company’s unique values for future employees and partners would be far more instrumental to long-term success. As we write this today, the arcane details of that IPO a decade ago are a matter of history, but phrases like “long term focus,” “serving end users,” “don’t be evil,” and “making the world a better place” still describe how the company is run.

There are other aspects of Google culture—about things like crowded offices, hippos, knaves, and Israeli tank commanders—that didn’t make the letter. But these, as we shall see, would become integral to creating—and sustaining—a culture where a simple statement like “These ads suck” is all that’s needed to make things happen.

Keep them crowded

A new visitor to the Googleplex will immediately notice the dazzling array of amenities available to employees: volleyball courts, bowling alleys, climbing walls and slides, gyms with personal trainers and lap pools, colorful bikes to get from building to building, free gourmet cafeterias, and numerous kitchens stocked with all sorts of snacks, drinks, and top-of-the-line espresso machines. These things usually leave visitors with the correct impression that Googlers are awash in luxuries, and the mistaken impression that luxury is part of our culture. Giving hardworking employees extra goodies is a Silicon Valley tradition dating back to the 1960s, when Bill Hewlett and David Packard bought a few hundred acres of land in the Santa Cruz Mountains and turned it into Little Basin29—a camping and recreational retreat for employees and their families.30 In the 1970s, companies such as ROLM started bringing the amenities closer to work, with full gymnasiums and subsidized cafeterias that served gourmet food, and Apple chipped in with its legendary (at least among the hookup-hopeful geek set) Friday afternoon beer busts. In Google’s case, our approach to facilities was grounded in the company’s beginnings in a Stanford dorm room. Larry and Sergey set out to create an environment similar to a university, where students have access to world-class cultural, athletic, and academic facilities… and spend most of their time working their butts off. What most outsiders fail to see when they visit Google is the offices where employees spend the bulk of their time. Follow your typical Googler (and probably LinkedIn, Yahoo, Twitter, or Facebook employee, although the last time we tried we got stopped by security) from the volleyball court, café, or kitchen back to their workspace and what will you find? A series of cubicles that are crowded, messy, and a petri dish for creativity.

Are you in your office right now? Are your coworkers nearby? Spin around and wave your arms. Do you hit anyone? If you have a quiet conversation on your phone while sitting at your desk, can your coworkers hear you? We’re guessing no. Are you a manager? If so, can you close your door and have private conversations? We’re guessing yes. In fact, your company’s facilities master plan was most likely specifically designed to maximize space and quiet (while minimizing cost). And the higher you are on the corporate hierarchy, the more space and quiet you get. Entry-level associates are shoehorned into interior cubicles, while CEOs get the big corner office with lots of space outside the door to house assistants and act as a barrier against everyone else.

Humans are by nature territorial, and the corporate world reflects this. In most companies the size of your office, the quality of your furniture, and the view from your window connote accomplishment and respect. Conversely, nothing reduces smart people to whiny complainers as quickly as a new office floor plan. It’s not uncommon for interior design to become a passive-aggressive means of literally keeping people “in their place.” When Eric was at Bell Labs, he had a boss whose office was chronically cold, so he bought a carpet for his cement floor. HR made him take it out because he wasn’t a high-enough-level employee to have such a fine amenity. That was a place where all privileges were accorded by tenure, not need or merit.

Silicon Valley is not immune to this syndrome. After all, it’s the place that turned the Aeron chair into a status symbol. (“It’s because of my back,” a legion of dot-com CEOs claimed. Really? At over $500 a pop, those chairs had better fix your front and sides too.) But the facilities-first culture needs to be killed, shot dead before it gains an insidious foothold in the building. Offices should be designed to maximize energy and interactions, not for isolation and status. Smart creatives thrive on interacting with each other. The mixture you get when you cram them together is combustible, so a top priority must be to keep them crowded.

When you can reach out and tap someone on the shoulder, there is nothing to get in the way of communications and the flow of ideas. The traditional office layout, with individual cubicles and offices, is designed so that the steady state is quiet. Most interactions between groups of people are either planned (a meeting in a conference room) or serendipitous (the hallway / water cooler / walking through the parking lot meeting). This is exactly backward; the steady state should be highly interactive, with boisterous, crowded offices brimming with hectic energy. Employees should always have the option to retire to a quiet place when they’ve had it with all the group stimulation, which is why our offices include plenty of retreats: nooks in the cafés and microkitchens, small conference rooms, outdoor terraces and spaces, and even nap pods. But when they go back to their desk, they should be surrounded by their teammates.

When Jonathan worked at Excite@Home, the company’s facilities team leased a second building to house customer support. But when the time came to move everyone to the new space, the management team overruled facilities and kept the support staff crowded in its original offices for a few more months. The new building was used to host lunchtime soccer games (making the new corner offices corner-kick offices). The soccer games brought people together, whereas putting people in that uncrowded space would have pulled them apart. Keeping people crowded also has the collateral benefit of killing facilities envy. When no one has a private office, no one complains about it.

Work, eat, and live together

And who should be in those jam-packed cubicles? We think it’s particularly important for teams to be functionally integrated. In too many places, employees are segregated by what they do, so product managers might sit here but the engineers are kept in that building across the street. This can work for traditional product managers, who are usually good with PERT and Gantt charts31 and at making themselves seem critical to the execution of the “Official Plan” that management bought into after seeing a fancy PowerPoint that projected financial returns above the company’s cost of capital hurdle rate. They are there to deliver against the defined plan, navigate any obstacles, “think outside the box” (which has to be the most inside-the-box phrase ever uttered), and obsequiously pander to late requests from the CEO and figure out how to push their team to get them done. This means that it’s OK, and sometimes better, for product managers to sit in a different location from engineers, as long as they can depend on regular work-process updates and detailed status reports to keep their finger on the pulse of their product. Not that we have any strong opinions on the matter, but let’s just say this is a twentieth-century product manager’s job, not a twenty-first-century one.

In the Internet Century, a product manager’s job is to work together with the people who design, engineer, and develop things to make great products. Some of this entails the traditional administrative work around owning the product life cycle, defining the product roadmap, representing the voice of the consumer, and communicating all that to the team and management. Mostly, though, smart-creative product managers need to find the technical insights that make products better. These derive from knowing how people use the products (and how those patterns will change as technology progresses), from understanding and analyzing data, and from looking at technology trends and anticipating how they will affect their industry. To do this well, product managers need to work, eat, and live with their engineers (or chemists, biologists, designers, or whichever other types of smart creatives the company employs to design and develop its products).

Your parents were wrong—messiness is a virtue

When offices get crowded, they tend to get messy too. Let them. When Eric first arrived at Google in 2001, he asked the head of facilities, George Salah, to clean up the place. George did, and was rewarded with a note the next day from Larry Page saying, “Where did all my stuff go?” That random collection of stuff was an icon of a busy, stimulated workforce.32 When she was at Google, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg gave people in her sales and support team fifty dollars apiece to decorate their space, while Jonathan ran a worldwide “Googley Art Wall” contest that had teams decorating office walls with Google logos fashioned from Rubik’s Cubes, photomosaics, and paint shot from paintball guns (the Chicago office, decorating Al Capone–style). The late Carnegie Mellon professor Randy Pausch, in his notable Last Lecture,33 showed off photos of his childhood bedroom with walls covered with his handwritten formulas. He told parents in the room, “If your kids want to paint their bedrooms, as a favor to me, let ’em do it.” Messiness is not an objective in itself (if it was, we know some teens who would be great hires), but since it is a frequent by-product of self-expression and innovation, it’s usually a good sign.34 And squashing it, which we’ve seen in so many companies, can have a surprisingly powerful negative effect. It’s OK to let your office be one hot mess.

But while offices can be crowded and messy, they need to provide employees with everything they need to get the job done. In our case, Google is a computer science company, so the thing that our smart creatives need most is computing power. That’s why we give our engineers access to the world’s most powerful data centers and Google’s entire software platform. This is another way to kill facilities envy among smart creatives: Be very generous with the resources they need to do their work. Be stingy with the stuff that doesn’t matter, like fancy furniture and big offices, but invest in the stuff that does.

There is a method to this madness, and it’s not profligacy. We invest in our offices because we expect people to work there, not from home. Working from home during normal working hours, which to many represents the height of enlightened culture, is a problem that—as Jonathan frequently says—can spread throughout a company and suck the life out of its workplace. Mervin Kelly, the late chairman of the board of Bell Labs, designed his company’s buildings to promote interactions between employees.35 It was practically impossible for an engineer or scientist to walk down the long halls without running into a colleague or being pulled into an office. This sort of serendipitous encounter will never happen when you are working at home. Google’s AdSense36 product, which developed into a multibillion-dollar business, was invented one day by a group of engineers from different teams who were playing pool in the office. Your partner or roommate is probably great, but the odds of the two of you coming up with a billion-dollar business during a coffee break at home are pretty small, even if you do have a pool table. Make your offices crowded and load them with amenities, then expect people to use them.

Don’t listen to the HiPPOs

Hippopotamuses are among the deadliest animals, faster than you think and capable of crushing (or biting in half) any enemy in their path. Hippos are dangerous in companies too, where they take the form of the Highest-Paid Person’s Opinion. When it comes to the quality of decision-making, pay level is intrinsically irrelevant and experience is valuable only if it is used to frame a winning argument. Unfortunately, in most companies experience is the winning argument. We call these places “tenurocracies,” because power derives from tenure, not merit. It reminds us of our favorite quote from Jim Barksdale, erstwhile CEO of Netscape: “If we have data, let’s look at data. If all we have are opinions, let’s go with mine.”37

When you stop listening to the hippos, you start creating a meritocracy, which our colleague Shona Brown concisely describes as a place where “it is the quality of the idea that matters, not who suggests it.” Sounds easy, but of course it isn’t. Creating a meritocracy requires equal participation by both the hippo, who could rule the day by fiat, and the brave smart creative, who risks getting trampled as she stands up for quality and merit.

Sridhar Ramaswamy, one of Google’s ads leaders, told a story at a Google meeting that illustrates this nicely. It was early in the days of AdWords, Google’s flagship ads product, and Sergey Brin had an idea for something he wanted Sridhar’s engineering team to implement. There was no doubt Sergey was the highest-paid person in the room, but he didn’t make a compelling argument as to why his idea was the best, and Sridhar didn’t agree with it. Sridhar wasn’t a senior executive at the time, so as the hippo, Sergey could have simply ordered Sridhar to comply. Instead, he suggested a compromise. Half of Sridhar’s team could work on what Sergey wanted, and the other half would follow Sridhar’s lead. Sridhar still disagreed, and after much debate about the relative merits of the competing ideas, Sergey’s idea was discarded.

This outcome was possible only because Sergey, as a smart creative, deeply understood the data being presented, the technology of the platform, and the context of the decision. The hippo who doesn’t understand what’s going on is more apt to try to intimidate her way to success. If you are in a position of responsibility but are overwhelmed by the job, it’s easier to try to bluster your way through with a “because I said so” approach. You need to have confidence in your people, and enough self-confidence to let them identify a better way.

Sergey also didn’t mind ceding control and influence to Sridhar, because he knew that in Sridhar he had hired someone who was quite likely to have ideas better than his own. His job as the hippo was to get out of the way if he felt his idea wasn’t the best. Sridhar also had a job to do: He had to speak up. For a meritocracy to work, it needs to engender a culture where there is an “obligation to dissent”.38 If someone thinks there is something wrong with an idea, they must raise that concern. If they don’t, and if the subpar idea wins the day, then they are culpable. In our experience, most smart creatives have strong opinions and are itching to spout off; for them, the cultural obligation to dissent gives them freedom to do just that. Others, though, may feel more uncomfortable raising dissenting views, particularly in a public forum. That’s why dissent must be an obligation, not an option. Even the more naturally reticent people need to push themselves to take on hippos.

Meritocracies yield better decisions and create an environment where all employees feel valued and empowered. They demolish the culture of fear, the murky, muddy environment in which hippos prefer to wallow. And they remove biases that can hamper greatness. Our colleague Ellen West related a story to us that was told to her by a member of the Gayglers (Google’s diversity group for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender employees). He told Ellen that the Gayglers had discussed whether or not Google could be considered the first “post-gay” company at which they had worked. The consensus was that it was close, since at Google “it doesn’t matter who you are, just what you do.” Bingo.

The rule of seven

Reorganization is one of the most despised phrases in the corporate lexicon, perhaps matched only by “outsourcing” and “eighty-slide presentation.” An executive decides that the way the company is structured is the source of its problems, and if the company was organized differently everything would be puppies and sunshine. So the company lurches from centralized organization to decentralized, or from functional to divisional. Some execs “win” and others “lose.” Meanwhile, most employees remain in limbo, wondering if they still have jobs, and if so, who their new boss will be and whether they’ll get to keep their nice cube next to the window. Then a year or two later some other executive (or quite possibly the same one) realizes the company still has problems and orders another reorganization. Such is the glorious “for loop”39 of corporate life.

Organizational design is hard. What works when you’re small and in one location does not work when you get bigger and have people all over the world. This is why there are so many reorgs: If there is no perfect answer, companies lurch between the less-than-optimal alternatives. To help avoid this dance, the best approach is to put aside preconceived notions about how the company should be organized, and adhere to a few important principles.

First, keep it flat. In most companies, there is a basic underlying tension: People claim that they want a flat organization so they can be closer to the top, but in fact they usually long for hierarchy. Smart creatives are different: They prefer a flat organization, less because they want to be closer to the top and more because they want to get things done and need direct access to decision-makers. Larry and Sergey once tried to accommodate this need by abolishing managers altogether; they called it a “dis-org.” At one point the head of engineering, Wayne Rosing, had 130 direct reports. But smart creatives aren’t that different; like any other employee, they still need a formal organization structure. The no-manager experiment ended and Wayne got to see his family again.

The solution we finally hit upon was slightly less draconian but just as simple. We call it the rule of seven. We’ve worked at other companies with a rule of seven, but in all of those cases the rule meant that managers were allowed a maximum of seven direct reports. The Google version suggests that managers have a minimum of seven direct reports (Jonathan usually had fifteen to twenty when he ran the Google product team). We still have formal organization charts, but the rule (which is really more of a guideline, since there are exceptions) forces flatter charts with less managerial oversight and more employee freedom. With that many direct reports—most managers have a lot more than seven—there simply isn’t time to micromanage.

Every tub (not) on its own bottom

When Eric was at Sun and the company was growing quickly, the business was getting complex enough that the powers-that-be decided to reorganize into business units. The new units were called “planets,” because they revolved around Sun’s core business of selling computer servers, and each of them had its own profit-and-loss structure. (People within Sun often explained the separate P&L structure by saying “every tub has its own bottom,” probably because planets don’t have bottoms, tubs don’t rotate around the sun, or just saying “it’s how most big companies do it” wasn’t sufficient.)

The problem with this approach was that almost all of the company’s revenue came from the hardware business (the sun, not the planets), so it required a team of accountants to look at that revenue and allocate it among the planets. The structure of how this was all supposed to run was itself a secret, so much so that leaders of the business units were not allowed to have their own copy of the document that codified it. It was read aloud to them.

We believe in staying functionally organized—with separate departments such as engineering, products, finance, and sales reporting directly to the CEO—as long as possible, because organizing around business divisions or product lines can lead to the formation of silos, which usually stifle the free flow of information and people. Having separate P&Ls seems like a good way to measure performance, but it can have the unfortunate side effect of skewing leaders of a business unit are motivated to prioritize their unit’s P&L over the company’s. If you do have P&Ls, make sure they are driven by real external customers and partners. At Sun, the formation of the planets led to a huge loss of productivity, as leaders (and accountants) became focused not on creating great products that generate actual revenue, but on optimizing a number at the end of an accounting formula.

And whenever possible, avoid secret organizational documents.

Do all reorgs in a day

There are times when a reorganization actually does make sense. When that day comes, we have a couple of rules. First, beware of the tendencies of different groups: Engineers add complexity, marketing adds management layers, and sales adds assistants. Manage this (and being aware of it is a big first step). Second, do all reorgs in a day. This may seem impossible to accomplish, but there is a counterintuitive point working in its favor. When you have a company of smart creatives, you can tolerate messiness. In fact, it helps, because smart creatives find it empowering, not confusing.

When Nikesh Arora reorganized Google’s business organization—a team of thousands of people spanning sales, operations, and marketing—in 2012, he moved quickly, announcing the changes to his team before all the details were worked out. Google’s product line had expanded from just one main product, AdWords, to several offerings (including YouTube ads, Google Display Network, and Mobile Ads) in just a few years, spawning new sales teams and leading to some confusion in the field. Nikesh wanted—like many sales leaders with multiple products—to create a “One Google” organization that would return its focus to the customer. But unlike most sales leaders, Nikesh planned and executed the reorganization in just a few weeks (OK, it wasn’t a day, but as Clarence Darrow might point out, sometimes a day doesn’t literally mean twenty-four hours),40 knowing that his team would jump in and finish the job. Over the next few months, the business team did make several adjustments, staying true to the intent of the changes while making them work better. The key was doing the reorg quickly and launching it before it was complete. As a result, the organization design was stronger than initially conceived, and the team was more invested in its success because it helped create the end result. Since there is no perfect organizational design, don’t try to find one. Get as close as you can and let your smart creatives figure out the rest.

The Bezos two-pizza rule

The building block of organizations should be small teams. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder, at one point had a “two-pizza team” rule,41 which stipulates that teams be small enough to be fed by two pizzas. Small teams get more done than big ones, and they spend less time politicking and worrying about who gets credit. Small teams are like families: They can bicker and fight, or even be downright dysfunctional, but they usually pull together at crunch time. Small teams tend to get bigger as their products grow; things built by only a handful of people eventually require a much bigger team to maintain them. This is OK, as long as the bigger teams don’t preclude the existence of small teams working on the next breakthroughs. A scaling company needs both.

Organize the company around the people whose impact is the highest

One last organizational principle: Determine which people are having the biggest impact and organize around them. Decide who runs the company not based on function or experience, but by performance and passion. Performance should be relatively easy to measure, but passion can be trickier to gauge. It is native in the best leaders—the sort of people who are elected captain of the team without even volunteering—and it draws others to them like iron filings to a magnet. Bill Campbell, the former Intuit CEO and ongoing coach and mentor to us both, often quotes Debbie Biondolillo, Apple’s former head of human resources, who said, “Your title makes you a manager. Your people make you a leader.”

Eric once chatted with Warren Buffett about what he looks for when acquiring companies. His answer was: a leader who doesn’t need him. If the company is run by a person who is performing well because she is committed to its success, and not just by making a bundle by selling to Berkshire Hathaway, then Warren will invest. Internal teams work in much the same way: You want to invest in the people who are going to do what they think is right, whether or not you give them permission. You’ll find that those people will usually be your best smart creatives.

This does not mean you should create a star system, in fact the best management systems are built around an ensemble, more like a dance troupe than a set of coordinated superstars. This approach creates long-term consistency, with a deep bench of high-performance talent ready to lead when the opportunity appears.

At the most senior level, the people with the greatest impact—the ones who are running the company—should be product people. When a CEO looks around her staff meeting, a good rule of thumb is that at least 50 percent of the people at the table should be experts in the company’s products and services and responsible for product development. This will help ensure that the leadership team maintains focus on product excellence. Operational components like finance, sales, and legal are obviously critical to a company’s success, but they should not dominate the conversation.

You also want to select as your leaders people who don’t place their own interests above the company’s. We see this a lot in companies with business units or divisions, where the success of the unit, as we noted before, can take precedence over that of the company as a whole. Once, when he was at Sun, Eric needed a new server. It was during the holidays, so rather than ordering one through the internal purchasing system he just went down to the warehouse and pulled a system from the shelves. He opened the box and found six “Read me first” documents, each one representing a division whose hippo felt its message was the most important.

A lot of government websites are guilty of this. (TV remotes too. At least, that’s the only explanation we can conceive for why they are so horrible. Seriously, why is the mute button tiny and hidden, while the “on demand” button is big and a different color? Because the exec who runs the on-demand business unit has a number to hit, and no one gets paid when viewers mute ads.) You should never be able to reverse engineer a company’s organizational chart from the design of its product. Can you figure out who reigns supreme at Apple when you open the box for your new iPhone? Yes. It’s you, the customer; not the head of software, manufacturing, retail, hardware, apps, or the Guy Who Signs the Checks. That is exactly as it should be.

Once you identify the people who have the biggest impact, give them more to do. When you pile more responsibility on your best people, trust that they will keep taking it on or tell you when enough is enough. As the old saying goes: If you want something done, give it to a busy person.

Exile knaves but fight for divas

Remember the childhood riddle about knights and knaves? You are on an island with knights, who always tell the truth, and knaves, who always lie. You stand at a fork in a road. One way leads to freedom, the other to death. There are two people standing there, one a knight and the other a knave, but you don’t know which is which. You get to ask one yes/no question to determine which way to go. What do you do?42

Life is something like that island, only more complicated. For not only are knaves in real life devoid of integrity, they are also sloppy, selfish, and have a sneaky way of working their way into virtually any company. Arrogance, for example, is a knavish tendency that is a natural by-product of success, since exceptionalism is fundamental to winning. Nice humble engineers have a way of becoming insufferable when they think they are the sole inventors of the world’s next big thing. This is quite dangerous, as ego creates blind spots.

There are other things that classify people as knaves. Jealous of your colleague’s success? You’re a knave. (Remember that famous knave Iago, warning the smart creative Othello to “beware, my lord, of jealousy. It is the green-eye’d monster, which doth mock the meat it feeds on.”43) Taking credit for someone else’s work? Knave. Selling a customer something she doesn’t need or won’t benefit from? Knave. Blowing up a Lean Cuisine in the company microwave and not cleaning it up? Knave. Tagging the wall of a nave? Knave.

The character of a company is the sum of the characters of its people, so if you strive for a company of sterling character, that is the standard you must set for your employees. There is no room for knaves. And generally, in our experience, once a knave, always a knave. (Tom Peters: “There is no such thing as a minor lapse of integrity.”)

Fortunately, employee behavior is socially normative. In a healthy culture of knightish values, the knights will call out the knaves for their poor behavior until they either shape up or leave. (This is another argument for crowded offices: Humans are at their best when surrounded by social controls, and crowded offices have lots of social controls!) This is pretty effective for most knavish offenses, since knaves are generally more motivated by personal success than knights, and if they sense that their behavior is not a route to success they are more apt to leave. As a manager, if you detect a knave in your midst it’s best to reduce his responsibility and appoint a knight to assume it. And for more egregious offenses, you need to get rid of the knave, quickly. Think about the baby elephant seals (knaves) who try to steal milk from other baby seals’ mothers; they are bitten not only by the nursing mother but also by other female seals (knights).44 You must always be firm with the people who violate the basic interests of the company. Don’t bite them, but do act swiftly and decisively. Nip crazy in the bud.

There are tipping points in knave density. It approaches a critical mass—which is smaller than you think45—and people start to believe they need to be knave-like to succeed, which only exacerbates the problem. Smart creatives may have a lot of good traits, but they aren’t saints, so it’s important to watch your knave quotient.

Knaves are not to be confused with divas. Knavish behavior is a product of low integrity; diva-ish behavior is one of high exceptionalism. Knaves prioritize the individual over the team; divas think they are better than the team, but want success equally for both. Knaves need to be dealt with as quickly as possible. But as long as their contributions match their outlandish egos, divas should be tolerated and even protected. Great people are often unusual and difficult, and some of those quirks can be quite off-putting. Since culture is about social norms and divas refuse to be normal, cultural factors can conspire to sweep out the divas along with the knaves. As long as people can figure out any way to work with the divas, and the divas’ achievements outweigh the collateral damage caused by their diva ways, you should fight for them. They will pay off your investment by doing interesting things. (And if you have been reading this paragraph thinking “she” every time we mention diva, remember that Steve Jobs was one of the greatest business divas the world has ever known!)

Overworked in a good way

Work-life balance. This is another touchstone of supposedly “enlightened” management practices that can be insulting to smart, dedicated employees. The phrase itself is part of the problem: For many people, work is an important part of life, not something to be separated. The best cultures invite and enable people to be overworked in a good way, with too many interesting things to do both at work and at home. So if you are a manager, it’s your responsibility to keep the work part lively and full; it’s not a key component of your job to ensure that employees consistently have a forty-hour workweek.

We’ve both worked with young moms who go completely dark for a few hours in the evening, when they are with their families and putting their kids to bed. Then, around nine, the emails and chats start coming and we know we have their attention. (Dads too, but the pattern is especially true for the working moms.) Are they overworked? Yes. Do they have too much to do at home too? Yes. Are they sacrificing their family and life for work? Yes and no. They have made their lifestyle decisions. There are times when work overwhelms everything and they have to make sacrifices, and they accept that. But there are also those times when they sneak away for an afternoon to take the kids to the beach or—more likely—have the gang drop by the office for lunch or dinner. (Google’s main campus courtyard on a summer evening looks like family camp, there are so many children running around while their parents enjoy a nice dinner.) The intense stretches may last for weeks or even months, especially in start-ups, but they never last forever.

Manage this by giving people responsibility and freedom. Don’t order them to stay late and work or to go home early and spend time with their families. Instead, tell them to own the things for which they are responsible, and they will do what it takes to get them done. Give them the space and the freedom to make it happen. Marissa Mayer, who became one of Silicon Valley’s most famous working mothers not long after she took over as Yahoo’s CEO in 2012, says that burnout isn’t caused by working too hard, but by resentment at having to give up what really matters to you.46 Give your smart creatives control, and they will usually make their own best decisions about how to balance their lives.47

Keeping them in small teams can help too. In small teams, teammates are more apt to sense when one member is burning out and needs to go home early or take a vacation. A big team may think someone who takes a vacation is slacking off; a small team is happy to see that empty seat.

We encourage people to take real vacations, although not to promote “work-life balance.” If someone is so critical to the company’s success that he believes he can’t unplug for a week or two without things crashing down, then there is a larger problem that must be addressed. No one should or can be indispensable. Occasionally you will encounter employees who create this situation intentionally, perhaps to feed their ego or in the mistaken belief that “indispensability” equals job security. Make such people take a nice vacation and make sure their next-in-line fills in for them while they are gone. They will return refreshed and motivated, and the people who filled their shoes will be more confident. (This is a huge hidden benefit of people taking maternity and paternity leaves too.)

Establish a culture of Yes

We are both parents, so we understand through years of firsthand experience the dispiriting parental habit of the reflexive no. “Can I have a soda?” No. “Can I get two scoops of ice cream instead of one?” No. “Can I play video games even though my homework isn’t done?” No. “Can I put the cat in the dryer?” NO!

The “Just Say No” syndrome can creep into the workplace too. Companies come up with elaborate, often passive-aggressive ways to say no: processes to follow, approvals to get, meetings to attend. No is like a tiny death to smart creatives. No is a signal that the company has lost its start-up verve, that it’s too corporate. Enough no’s, and smart creatives stop asking and start heading to the exits.

To keep this from happening, establish a culture of Yes. Growing companies spawn chaos, which most managers try to control by creating more processes. While some of these processes may be necessary to help the company scale, they should be delayed for as long as possible. Set the bar high for that new process or approval gate; make sure there are very compelling business reasons for it to be created. We like this quote from American academic and former University of Connecticut president Michael Hogan: “My first word of advice is this: Say yes. In fact, say yes as often as you can. Saying yes begins things. Saying yes is how things grow. Saying yes leads to new experiences, and new experiences will lead you to knowledge and wisdom.… An attitude of yes is how you will be able to go forward in these uncertain times.”48

A few years ago the former head of YouTube, Salar Kamangar, had his own “attitude of yes” moment. It came during his weekly staff meeting, at which the testing of a new feature—high-definition playback—was being discussed. The testing was going well. So well, in fact, that Salar asked if there was any good reason the feature couldn’t be launched right away. “Well,” someone replied, “the schedule says it’s not supposed to be released for several more weeks, so we can test it further and make sure it works.” “Right,” Salar replied, “but besides the schedule is there any good reason we can’t launch it now?” No one could think of one, and high-def YouTube launched the next day. Nothing blew up, nothing broke, and millions of happy YouTube users benefited weeks early from one man’s commitment to saying yes.

fun, not Fun

Every week, at Google’s TGIF all-hands meeting, all the new hires are seated in one section and provided with multicolored propeller hats to identify them. Sergey warmly welcomes them, everyone applauds, then he says “Now get back to work.” It’s not the greatest joke, but delivered in Sergey’s deadpan tone and slightly Russian accent it always gets a hearty laugh. Among his other great talents, one of Sergey’s strengths as a leader of smart creatives is his sense of humor. When he hosts TGIF, his constant ad-libbed one-liners generate a lot of laughs—not laugh-at-the-founder’s-jokes-or-else laughs, but real laughs.

A great start-up, a great project—a great job, for that matter—should be fun, and if you’re working your butt off without deriving any enjoyment, something’s probably wrong. Part of the fun comes from inhaling the fumes of future success. But a lot of it comes from laughing and joking and enjoying the company of your coworkers.

Most companies try to manufacture Fun, with a capital F. As in: We are having the annual company picnic / holiday party / off-site on Friday. There will be Fun music. There will be Fun prizes. There will be a Fun contest of some sort that will embarrass some of your coworkers. There will be Fun face painting / clowns / fortune-tellers. There will be Fun food (but no Fun alcohol). You will go. You will have Fun. There’s a problem with these Fun events: They aren’t fun.

This doesn’t have to be the case. There’s nothing wrong with organized company events, as long as they are done with flair. In fact, it’s not hard to throw a fun company party. The formula is exactly the same as fun weddings: great people (and you did hire great people, didn’t you?) + great music + great food and drink. While the fun factor can be endangered by those guests who are congenitally unfun (Aunt Barbara from Boca Raton, Craig from accounting), there’s nothing a good ’80s cover band and a fine brew can’t fix. Everyone’s fun when they’re dancing to Billy Idol and swigging an Anchor Steam.

Then there are group or company off-sites. These are often justified as “team building” events that will help the group learn how to work together better. You go to the ropes course or chef’s class, take a personality test or solve a group problem, and just like that you will coalesce into a fine-tuned machine. Or not. Here’s our idea for off-sites: Forget “team building” and have fun. Jonathan’s criteria for his excursions included doing outdoor group activities (weather permitting) in a new place far enough from the office to feel like a real trip, but still doable in a day, and providing an experience that people couldn’t or wouldn’t have on their own.

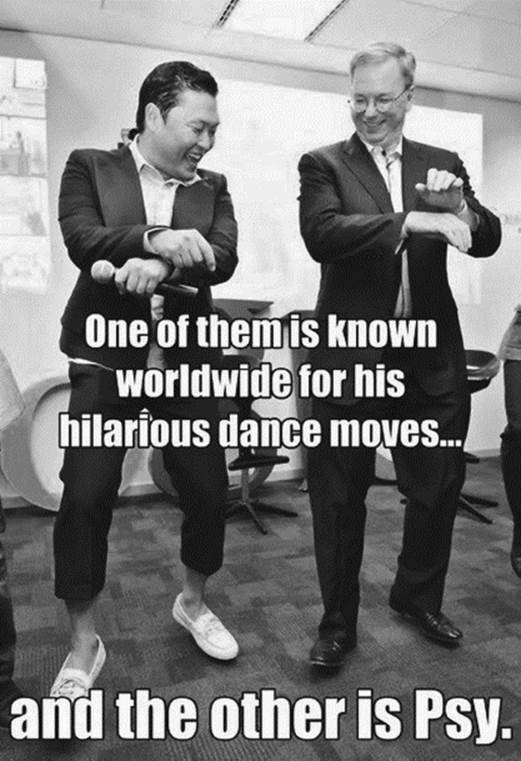

These rules have led Jonathan to take his teams on trips all over Northern California: to Muir Woods, Pinnacles National Park, Año Nuevo to see the famous elephant seals, and the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. These events don’t cost much—fun can be cheap (Fun, usually not). The price of admission to Larry and Sergey’s roller hockey games in Google’s early days was nothing more than a stick, a pair of skates, and the willingness to be hip-checked by a founder. Sheryl Sandberg ran a book club for her sales team that was so popular in our India office that every single person participated. Eric led the entire Seoul team in dancing “Gangnam Style” with Korean pop star PSY, who had come by the office for a visit. (Eric doesn’t adhere to Satchel Paige’s advice to “dance like nobody’s watching.” When you’re a leader, everyone is watching, so it doesn’t matter that you dance poorly, it matters that you dance.)

Jonathan once made a bet with head of marketing Cindy McCaffrey on whose team would have higher participation in the company’s annual employee feedback survey, Googlegeist. The loser had to wash the winner’s car. When Jonathan lost, Cindy rented a stretch Hummer, caked it in as much mud as possible (to this day we don’t know how), and then gathered her team so they could watch Jonathan wash the behemoth SUV and pelt him with water balloons while he was at it. Another time, Jonathan got the company basketball court built by bringing in a couple of hoop sets and challenging a few engineering teams to see who could put them together first. Some of these guys didn’t know a dunk from a dongle, but they knew an engineering challenge when they saw it.

A defining mark of a fun culture is identical to that of an innovative one: The fun comes from everywhere. The key is to set the boundaries of what is permissible as broadly as possible. Nothing can be sacred. In 2007, a few of our engineers discovered that Eric’s profile photo in our intranet system was in a public folder. They altered the background of the photo to include a portrait of Bill Gates, and, on April Fools’ Day, posted the updated image on Eric’s page. Any Googler who looked up Eric saw this:

Eric kept it as his profile photo for a month.

Smart-creative humor is often not quite as gentle as a photo of Bill Gates on a wall, which is where the loose boundaries come in. In October 2010, a couple of Google engineers named Colin McMillen49 and Jonathan Feinberg launched an internal site called Memegen, which lets Googlers create memes—pithy captions matched to images—and vote on each other’s creations. Memegen created a new way for Googlers to have fun while commenting acerbically on the state of the company. It has succeeded wildly on both fronts. In the fine tradition of Tom Lehrer and Jon Stewart, Memegen can be very funny while cutting to the heart of controversies within the company. To wit:

Eric is apparently popular with the memegeners:

Because a constant Google complaint is how things at the company used to be so much better:

An idea for a new Google Glass app:

After Project Loon (which we explain in more detail later in the book) was announced, one Googler felt that his OKRs (quarterly performance goals—they are also explained further on) needed revising:

Seoul dancing with Korean pop star PSY:

This isn’t Fun—it couldn’t possibly be created by fiat. It’s fun, and can only occur in a permissive environment that trusts its employees and doesn’t defer to the “what happens if this leaks?” worrywarts. It’s impossible to have too much of that kind of fun. The more you have, the more you get done.

You must wear something

Not long after he became the CEO of Novell, Eric heard a good piece of advice from an acquaintance. “When you are in a turnaround,” the man told him, “find the smart people first. And to find the smart people, find one of them.” A few weeks later, Eric was on a flight from San Jose to Utah (where the company is based) with a Novell engineer who impressed him. Eric remembered the advice he had received about turnarounds, stopped the smart engineer practically mid-sentence, and asked him to produce a list of the ten smartest people he knew at Novell. A few minutes later Eric had his list. He set up one-on-one meetings with each of the ten.

A couple of days later the first person on the list showed up in Eric’s office, white as a sheet. “Have I done something wrong?” he asked. The next few meetings started off in similar fashion. Each of the smart people arrived at the meeting defensive and fearful. Eric soon figured out that the way people were let go at Novell was in one-on-one meetings with the CEO. He had inadvertently scared some of the best people in the company into thinking they were being fired.

This was one of our early lessons in how difficult it can be to change the culture of an ongoing enterprise. The advice to find the smart people was sound, but its execution was disrupted by an incumbent culture that Eric hadn’t anticipated. While establishing a culture in a start-up is relatively easy, changing the culture of an ongoing enterprise is extraordinarily difficult, but even more critical to success: A stagnant, overly “corporate” culture is anathema to the average smart creative.

We have some recent hands-on experience with this scenario in our work at Motorola Mobility, which Google acquired in 2012.50 There are a couple of important steps to take. First, recognize the problem. What is the culture that defines your company today (not the one described by the mission or value statements, the real one that people live in every day)? What problems has this culture caused with the business? It is important not to simply criticize the existing culture, which will just insult people, but rather to draw a connection between business failures and how the culture may have played a hand in those situations.

Then articulate the new culture you envision—to borrow Nike’s advertising phrase from the 2010 World Cup, “write the future”—and take specific, high-profile steps to start moving that way. Promote transparency and sharing of ideas across divisions. Open up everyone’s calendar so that employees can see what other employees are doing. Hold more company-wide meetings and encourage honest questions without reprisal. And when you get those tough questions, answer them honestly and authentically. When Motorola was the topic one week at a TGIF meeting, several Googlers asked challenging questions about the company’s products, which were answered as well as possible. Later Jonathan overheard a few Motorolans wondering if the questioners would be fired. No, he told them.

Sometimes, when looking to redefine a culture, it can be useful to look at the original one. Lou Gerstner, who helped engineer a turnaround at IBM, notes in his book Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?, “It’s been said that every institution is nothing but the extended shadow of one person.51 In IBM’s case, that was Thomas J. Watson, Sr.”52 Gerstner goes on to talk about rebuilding IBM based on Watson’s core beliefs: excellence in everything they do, superior customer service, and respect for the individual. But while building on the legacy of that founder, don’t be afraid to scrap its obsolete trappings. Gerstner abolished the famous blue-suit, white-shirt dress code that Watson established, because it no longer served its purpose of showing respect for the customer. “We didn’t replace one dress code with another. I simply returned to the wisdom of Mr. Watson and decided: Dress according to the circumstances of your day and recognize who you will be with.”53

(Eric was once asked at a company meeting what the Google dress code was. “You must wear something” was his answer.)

This all takes a lot of time. The most important lesson from our Moto experience is something that many of you who work at incumbents may already know: Practicing what we preach in this book in the effort to change a culture takes a lot more time than expected.

Ah’cha’rye

As someone launching a new venture (or reinventing an established one), you are signing up for long days, sleepless nights, and maybe some missed birthday parties. You will hire people who need to believe in you and your idea enough to be willing to make the same sacrifices. To do all this, you have to be crazy enough to think you will succeed, but sane enough to make it happen. This requires commitment, tenacity, and most of all, single-mindedness. When Israeli tank commanders head into combat, they don’t yell “Charge!” Rather, they rally their troops by shouting “Ah’cha’rye,” which translates from Hebrew as “Follow me.” Anyone who aspires to lead smart creatives needs to adopt this attitude.

Eric once had a meeting with Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook headquarters in Palo Alto. At the time, it was already clear that Facebook and Mark were going to be massively successful. The two men chatted for a couple of hours, wrapping up around seven p.m. As Eric was leaving, an assistant brought Mark’s dinner and placed it next to his computer. Mark sat down and got back to work. There was no doubt where his commitment lay.

One of our early engineers, Matt Cutts, recalls how he would often see Urs Hölzle, the engineering executive who led the creation of Google’s data center infrastructure, picking up small bits of trash in the hallway as he walked through the office. This is a common refrain you hear in Silicon Valley: the CEO who picks up the stack of newspapers outside the front door, the founder who wipes the counters. With these actions, the leaders demonstrate their egalitarian natures—we’re all in this together and none of us are above the menial tasks that need to get done. Mostly, though, they do it because they care so much about the company. Leadership requires passion. If you don’t have it, get out now.

Don’t be evil

Eric had been at Google for about six months. By then he knew all about the company’s “Don’t be evil” mantra, which had been coined by engineers Paul Buchheit and Amit Patel during a meeting earlier in the company’s life. But he completely underestimated how much this simple phrase had become a part of the company’s culture. He was in a meeting in which they were debating the merits of a change to the advertising system, one that had the potential to be quite lucrative for the company. One of the engineering leads pounded the table and said, “We can’t do that, it would be evil.” The room suddenly got quiet; it was like a poker game in an old Western, when one player accuses another of cheating and everyone else backs away from the table, waiting for someone to draw. Eric thought, Wow, these guys take these things seriously. A long, sometimes contentious discussion followed, and ultimately the change did not go through.

The famous Google mantra of “Don’t be evil” is not entirely what it seems. Yes, it genuinely expresses a company value and aspiration that is deeply felt by employees. But “Don’t be evil” is mainly another way to empower employees. The experience Eric had was not unusual (except for the fist pounding): Googlers do regularly check their moral compass when making decisions.

When Toyota invented its famous kanban system of just-in-time production, one of its quality control rules was that any employee on the assembly line could pull the cord to stop production if he noticed a quality problem.54 That same philosophy lies behind our simple three-word slogan. When the engineer in Eric’s meeting called the proposed new feature “evil,” he was pulling the cord to stop production, forcing everyone to assess the proposed feature and determine if it was consistent with the company’s values. Every company needs a “Don’t be evil,” a cultural lodestar that shines over all management layers, product plans, and office politics.

This is the ultimate value of having a well-established and well-understood company culture. It becomes the basis for everything you and the company do; it is the safeguard against something going off the rails, because it is the rails. The best cultures are aspirational. For each of the components we discuss in this chapter, we have given examples where we have lived up to our ideals. But we could have just as easily talked about cases where we fell short. There will be failures, but there will be more cases where people overdeliver, and when that happens the bar gets set even higher. That is the power of a great culture: It can make each member of the company better. And it can make the company ascendant.