How Google Works

Talent—Hiring Is the Most Important Thing You Do

As Jonathan headed over to Mountain View one day in February 2000, to interview with Sergey for the role of product leader at Google, he assumed the meeting was a mere formality. As a senior VP at Excite@Home, he was quite happy in his current job and wasn’t sure he wanted to jump ship. But if he did, he fancied himself an expert in online search and advertising and he came recommended for the job by John Doerr, a partner at Kleiner Perkins and member of the Google and Excite@Home boards. So the job was certainly his for the asking, and Sergey would probably spend the interview time trying to convince him to take it.

Then he got to the crowded office on Bayshore Parkway, a stone’s throw from 101, and followed Sergey into a conference room. After a few pleasantries, Sergey asked one of his favorite interview questions: “Could you teach me something complicated I don’t know?” Jonathan was an economics major at Claremont McKenna and the offspring of a Stanford economist, so, after he got over his surprise that he was actually being interviewed, he launched into a whiteboard proof of the economic law that marginal cost bisects average cost at the latter’s minimum. From there he figured he could dazzle Sergey by demonstrating how to use cost and revenue functions to find the optimal point of production and profit by maximizing the firm’s output quantities. (For economics majors, this passes for pillow talk.) He soon realized, as Sergey started fiddling with his Rollerblades and looking out the window, that he was failing to address every aspect of the question. He wasn’t teaching Sergey anything, the economics law in question wasn’t interesting, and, as a math wizard, there was a good chance that Sergey already knew the calculus involved in resolving the economic formulas on the board. Jonathan needed to change tactics now. So he stopped the economics lesson and embarked on a new topic: courtship. It started with an explanation of how to “dangle the hook,” using Jonathan’s method for hooking a first date, with his wife as a case study.88 Sergey started paying attention, and Jonathan got the job.89

If you asked managers at large companies “What is the single most important thing you do at work?” most would reflexively answer “Go to meetings.” If you persisted—“No, not the most boring thing you do at work, the most important”—they would probably respond by spouting some of the standard principles they learned in business school, something about “devising smart strategies and creating opportunistic synergies to accumulate accretive financial effects in an increasingly competitive market.” Now imagine asking the same question of the top sports coaches or general managers. They go to meetings all day too, yet they would probably say that the most important thing they do is draft, recruit, or trade for the best players they can. Smart coaches know that no amount of strategy can substitute for talent, and that is as true in business as it is on the field. Scouting is like shaving: If you don’t do it every day, it shows.

For a manager, the right answer to the question “What is the single most important thing you do at work?” is hiring. When Sergey was interviewing Jonathan that day, he wasn’t just going through the paces, he was intent on doing a great job. At first Jonathan chalked this up to the fact that he would be a senior member of the team and would work closely with Sergey, but once he arrived at Google he realized that the company’s leaders pursued interviewing with the same level of intensity for every candidate. It didn’t matter if the person would be an entry-level software engineer or a senior executive, Googlers made it a priority to invest the time and energy to ensure they got the best possible people.

You would think this level of commitment would be common. But even though most managers get their own positions through the familiar hiring process—résumé, phone screen, interviews, more interviews, offer, haggling, more haggling, acceptance—once hired, they seemingly do everything in their power to avoid being involved in hiring anyone else. Recruiting is for recruiters. Reviewing résumés can be delegated to young associates or someone in human resources. Interviewing is a chore. That feedback form is so long and intimidating that the task of filling it out inevitably slides to late Friday afternoon, by which time the details of the interview have faded into a blur. So interviewers dash off a cursory report and hope that their colleagues do a better job with their interview feedback. The higher up you go in most organizations, the more detached the executives get from the hiring process. The inverse should be true.

There’s another, even more important aspect to hiring well in the Internet Century. The traditional hiring model is hierarchical: The hiring manager decides who gets the job, while other members of the team provide their input and senior executives rubber-stamp whatever decision the manager makes. The problem with this is that once that person starts at the company, the working model is (or should be) collaborative, with high degrees of freedom and transparency and a disdain for rank. So now a single hiring manager has made a decision that directly impacts numerous teams besides her own.

There’s another reason that hierarchical hiring doesn’t work. Leaders (and management book authors) often say they hire people smarter than themselves, but in practice this rarely happens in a hierarchical hiring process. The rational “let’s-hire-this-guy-because-he’s-so-smart” decision usually gets usurped by the more emotional “but-then-he-might-be-better-than-me-and-make-me-look-bad-and-then-I-won’t-get-promoted-and-my-kids-will-think-I’m-a-loser-and-my-wife-will-run-off-with-that-guy-from-Peet’s-Coffee-and-take-my-dog-and-truck” decision. In other words, human nature gets in the way.

From the outset, Google’s founders understood that to consistently hire the best people possible, the model to follow wasn’t that of corporate America, but that of academia. Universities usually don’t lay professors off, so they invest a lot of time in getting faculty hiring and promotion right, normally using committees. This is why we believe that hiring should be peer-based, not hierarchical, with decisions made by committees, and it should be focused on bringing the best possible people into the company, even if their experience might not match one of the open roles. Eric hired Sheryl Sandberg even though he didn’t have a job for her. It didn’t take long for her to assume the task of building our small business sales team, a role that didn’t formally exist until she helped create it. (Of course, Sheryl later left us and became COO of Facebook and a best-selling author. When you hire smart creatives, some of them eventually smartly create opportunities for themselves outside the company. More on that later in the chapter.) In a peer-based hiring process, the emphasis is on people, not organization. The smart creatives matter more than the role; the company matters more than the manager.

“Our people are our most important asset” is a well-worn cliché, but building a team of smart creatives that lives up to that statement requires more than just saying the words: You need to change how the members of the team are hired. The nice thing about these changes is that anyone can make them. Some of the culture recommendations that we made in the earlier chapter may be challenging for ongoing companies to adopt, but anyone can change how they hire. The not-so-nice thing is that hiring well takes a lot of work and time. But it is the best investment you can make.

The herd effect

A workforce of great people not only does great work, it attracts more great people.90 The best workers are like a herd: They tend to follow each other. Get a few of them, and you’re guaranteed that a bunch more will follow. Google is renowned for its fabulous amenities, but most of our smart creatives weren’t drawn to us because of our free lunches, subsidized massages, green pastures, or dog-friendly offices. They came because they wanted to work with the best smart creatives.

This “herd effect” can cut both ways: While A’s tend to hire A’s, B’s hire not just B’s, but C’s and D’s too. So if you compromise standards or make a mistake and hire a B, pretty soon you’ll have B’s, C’s, and even D’s in your company. And regardless of whether it works to the benefit or detriment of the company, the herd effect is more powerful when the employees are smart creatives and the company is new. In that case, each person’s relative importance is magnified; early employees are more conspicuous. Also, when you put great people with great people, you create an environment where they will share ideas and work on them. This is always true, but particularly in an early-stage environment.

A positive people herd effect can be orchestrated. “You’re brilliant, we’re hiring,” the phrase adorning Google’s early ads recruiting new employees,91 was a clever Marxist trick. Not Karl, Groucho, since it was designed to inspire a response along the lines of “Yes, I do want to belong to this club that wants me as a member!” The intent was to let the world know that we set the hiring bar quite high, and rather than dissuading applicants, this became a recruiting tool in itself. Jonathan used to keep a stack of résumés of the people he had hired in his desk, and when he was trying to close a candidate, he’d hand over the résumés and show the person the team she’d be joining. These weren’t just a cherry-picked group of Jonathan’s best hires, they were the entire set. That was a club our smart-creative Grouchos usually wanted to join. So set the bar high from the very beginning, and then shout it from the rafters.

This is especially important for product people, because they can have such a big impact. Pay close attention to hiring them, and when your process guarantees excellence at the product core of the company, it will spill over to every other team as well. The objective is to create a hiring culture that resists the siren song of compromise, a song that only gets louder amidst the chaotic whirlwind of hypergrowth.

Passionate people don’t use the word

A fine marker of smart creatives is passion. They care. So how do you figure out if a person is truly passionate, since truly passionate people don’t often use the “P-word”? In our experience, a lot of job candidates have figured out that passion is a sought-after trait. When someone begins a sentence with the conspicuously obvious phrase “I’m passionate about…” and then proceeds to talk about something generic like travel, football, or family, that’s a red flag that maybe his only true passion is for conspicuously throwing the word “passion” around a lot during interviews.

Passionate people don’t wear their passion on their sleeves; they have it in their hearts. They live it. Passion is more than résumé-deep, because its hallmarks—persistence, grit, seriousness, all-encompassing absorption—cannot be gauged from a checklist. Nor is it always synonymous with success. If someone is truly passionate about something, they’ll do it for a long time even if they aren’t at first successful. Failure is often part of the deal. (This is one reason we value athletes, because sports teach how to rebound from loss, or at least give you plenty of opportunities to do so.) The passionate person will often talk at length, aka ramble, about his pursuits. This pursuit can be professional. In our world, “perfecting search” is a great example of something people can spend an entire career on and still find challenging and engaging every day. But it can also be a hobby. Andy Rubin, who started Android, loves robots (and is now spearheading Google’s nascent efforts in that area). Wayne Rosing, Google’s first head of engineering, loves telescopes. Captain Eric loves planes and flying (and telling stories of flying planes).

More often than not, these seemingly extracurricular passions can yield direct benefits to a company. Android’s great Sky Map is an astronomy application that turns a phone into a star chart. It was built by a team of Googlers in their spare time (what we call “20 percent time”—more on that later), not because they love to program computers, but because they were enthusiastic amateur astronomers.92 We have been just as impressed by one candidate who studied Sanskrit, and another who loved restoring old pinball machines. Their deep interest made them more interesting, which is why in an interview context our philosophy is not “Don’t get them started.” When it comes to the things they care most about, we want to get them started.

Once they start, listen very carefully. Pay attention to how they are passionate. For example, athletes can be quite passionate, but do you want the triathlete or ultramarathoner who pursues his craft all alone, or someone who trains with a group? Is the athlete solo or social, exclusive or inclusive? When people are talking about their professional experience, they know the right answers to these questions—most people don’t like a loner in the work environment. But when you get people talking about their passions, the guard usually comes down and you gain more insight into their personalities.

Hire learning animals

Think about your employees. Which of them can you honestly say are smarter than you? Who among them would you not want to face across a chessboard, on Jeopardy!, or in a crossword-puzzle duel? The adage is to always hire people who are smarter than you. How well do you follow it?

This adage still holds true, but not for the obvious reasons. Of course smart people know a lot and can therefore accomplish more than others less gifted. But hire them not for the knowledge they possess, but for the things they don’t yet know. Ray Kurzweil said that “information technology’s growing exponentially… And our intuition about the future is not exponential, it’s linear.”93 In our experience raw brainpower is the starting point for any exponential thinker. Intelligence is the best indicator of a person’s ability to handle change.

It is not, however, the only ingredient. We know plenty of very bright people who, when faced with the roller coaster of change, will choose the familiar spinning-teacups ride instead. They would rather avoid all those gut-wrenching lurches; in other words, reality. Henry Ford said that “anyone who stops learning is old, whether at twenty or eighty. Anyone who keeps learning stays young. The greatest thing in life is to keep your mind young.”94 Our ideal candidates are the ones who prefer roller coasters, the ones who keep learning. These “learning animals” have the smarts to handle massive change and the character to love it.

Psychologist Carol Dweck has another term for it. She calls it a “growth mindset.”95 If you believe that the qualities defining you are carved in stone, you will be stuck trying to prove them over and over again, regardless of the circumstances. But if you have a growth mindset, you believe the qualities that define you can be modified and cultivated through effort. You can change yourself; you can adapt; in fact, you are more comfortable and do better when you are forced to do so. Dweck’s experiments show that your mindset can set in motion a whole chain of thoughts and behaviors: If you think your abilities are fixed, you’ll set for yourself what she calls “performance goals” to maintain that self-image, but if you have a growth mindset, you’ll set “learning goals”96—goals that’ll drive you to take risks without worrying so much about how, for example, a dumb question or a wrong answer will make you look. You won’t care because you’re a learning animal, and in the long run you’ll learn more and scale greater heights.97

Most people, when they are hiring for a role, look for people who have excelled in that role before. This is not how you find a learning animal. Peruse virtually any job listing and one of the top criteria for a position will be relevant experience. If the job is for chief widget designer, it’s a given that high on the list of requirements will be five to ten years of widget design and a degree from Widget U.

Favoring specialization over intelligence is exactly wrong, especially in high tech. The world is changing so fast across every industry and endeavor that it’s a given the role for which you’re hiring is going to change. Yesterday’s widget will be obsolete tomorrow, and hiring a specialist in such a dynamic environment can backfire. A specialist brings an inherent bias to solving problems that spawns from the very expertise that is his putative advantage, and may be threatened by a new type of solution that requires new expertise. A smart generalist doesn’t have bias, so is free to survey the wide range of solutions and gravitate to the best one.

Finding learning animals can be a challenge. Jonathan’s modus operandi is to ask candidates to reflect on a past mistake. In the early 2000s, he used to ask candidates “What big trend did you miss about the Internet in 1996? What did you get right, and what did you get wrong?” It’s a deceptively tricky question. It makes candidates define what they expected, link it to what they observed and explore the revelations, and forces them to admit a mistake—and not in the lame, my-biggest-weakness-is-that-I’m-a-perfectionist sort of way. It’s impossible to fake the answer.

The question can be adapted to any big events of the recent past. The point is not to see if someone was prescient, but rather how she evolved her thinking and learned from her mistakes. Few people answer this question well, but when they do, it’s a great indication that you’re talking to a learning animal. Of course, they could just come out and tell you, “I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious.”98 That’s what Albert Einstein claimed, and we would have hired him in an instant (despite his use of the P-word; devising the theory of relativity trumps that).

Once you hire those learning animals, keep learning them!99 Create opportunities for every employee to be constantly learning new things—even skills and experiences that aren’t directly beneficial to the company—and then expect them to use them. This won’t be challenging for true learning animals, who will gladly avail themselves of training and other opportunities. But keep an eye on the people who don’t; perhaps they aren’t quite the learning animals you thought they were.

The LAX test

So, passion is crucial in a potential hire, as is intelligence and a learning-animal mindset. Another crucial quality is character. We mean not only someone who treats others well and can be trusted, but who is also well-rounded and engaged with the world. Someone who is interesting.

Judging character during the interview process used to be fairly easy, since job interviews often included lunch or dinner at a restaurant and perhaps a drink or two, Mad Men style. Such a venue allowed the hiring executive to observe how the candidate comported himself “as a civilian.” What happens when he lets his guard down? How does he treat the waiter and bartender? Great people treat others well, regardless of standing or sobriety.

Today you usually don’t get to get candidates drunk, so you need to be more observant, especially during the before-and-after spaces of the interview. Jonathan interviewed for a job at a big consulting firm his second year in business school. His competition for the position was a fortunate and highly pedigreed fellow—Jonathan is sure his name was Hodsworth Bodsworth III—who was not only far more qualified than Jonathan, but better looking too. Jonathan was certainly doomed: Bodsworth was bound to get the job. But while Jonathan waited for his interview to start, he chatted with the administrative assistant and learned she was planning a trip to California, his home state. Soon he was giving her travel advice and recommending sites to see. When the firm called the next day to discuss an offer, he figured that either there was a mistake or two people were getting hired. But no. Bodsworth didn’t get hired because, according to the interviewer, “He was an asshole to my secretary, and she likes you.” We usually ask our assistants what they think of candidates, and listen to their response. Call it the Bodsworth rule.

As important as character, though, is whether or not a candidate is interesting. Imagine being stuck at an airport for six hours with a colleague; Eric always chooses LAX for maximum discomfort (although Atlanta or London will do in a pinch). Would you be able to pass the time in a good conversation with him? Would it be time well spent, or would you quickly find yourself rummaging through your carry-on for your tablet so you can read your latest email or the news or anything to avoid having to talk to this dull person? (TV star Tina Fey has her own version of the LAX test, which she credits to Saturday Night Live producer Lorne Michaels: “Don’t hire anyone that you wouldn’t want to run into by the bathrooms at three in the morning, because you’re going to be [in the office] all night.”)100

We institutionalized the LAX test by making “Googleyness” one of four standard sections—along with general cognitive ability, role-related knowledge, and leadership experience—on our interview feedback form. This includes ambition and drive, team orientation, service orientation, listening & communication skills, bias to action, effectiveness, interpersonal skills, creativity, and integrity.

(Larry and Sergey took the LAX test one step further when they were looking for a CEO: They took candidates away for a weekend. Eric played it a bit more conservatively: “Look, guys, I don’t need to go to Burning Man with you. How about dinner?”)

Insight that can’t be taught

A person who passes the LAX/Googleyness/three-a.m.-in-the-SNL-bathroom test has to be someone you could have an interesting conversation with and respect. However, he or she is not necessarily someone you have to like. Imagine that person with whom you are stuck at LAX has nothing in common with you, and in fact represents the polar opposite of wherever you stand on the political spectrum. Yet if this person is your equal (or more) in intellect, creativity, and these factors we call Googleyness, the two of you would still have a provocative conversation, and your company will be better off having the both of you on the same team.

You often hear people say they only want to work with (or elect as president) someone they would want to have a beer with. Truth be told, some of our most effective colleagues are people we most definitely would not want to have a beer with. (In a few rare instances they are people we would rather pour a beer on.) You must work with people you don’t like, because a workforce comprised of people who are all “best office buddies” can be homogeneous, and homogeneity in an organization breeds failure. A multiplicity of viewpoints—aka diversity—is your best defense against myopia.

We could go off on a politically correct tangent on how hiring a workforce that is diverse in terms of race, sexual orientation, physical challenges, and anything else that makes people different is the right thing to do (which it is). But from a strictly corporate point of view, diversity in hiring is even more emphatically the right thing to do. People from different backgrounds see the world differently. Women and men, whites and blacks, Jews and Muslims, Catholics and Protestants, veterans and civilians, gays and straights, Latinos and Europeans, Klingons and Romulans,101 Asians and Africans, wheelchair-bound and able-bodied: These differences of perspective generate insights that can’t be taught. When you bring them together in a work environment, they integrate to create a broader perspective that is priceless.102

Great talent often doesn’t look and act like you. When you go into that interview, check your biases at the door103 and focus on whether or not the person has the passion, intellect, and character to succeed and excel.

The same goes for managing people once they join you. Just like hiring, managing performance should be driven by data, with the sole objective of creating a meritocracy. You cannot be gender-, race-, and color-blind by fiat; you need to create empirical, objective methods to measure people. Then the best will thrive, regardless of where they’re from and what they look like.

Expand the aperture

The ideal candidate is out there. She has passion, intellect, integrity, and a unique perspective. Now, how do you find her and get her on board? There are four links in this critical chain: sourcing, interviewing, hiring, and compensation.

Let’s start with sourcing, which in turn starts with defining the type of candidate for whom you are looking. Our recruiting partner Martha Josephson calls this “expanding the aperture.” The aperture is the opening in a camera through which light flows to the sensors that capture the image. A typical hiring manager will have a narrow aperture, considering only certain people with certain titles in certain fields, those who will undoubtedly do today’s job well. But the successful manager sets a wider aperture and rounds up people beyond the usual suspects.

Let’s say you like to hire people from a particular company, one that is well known for harboring tremendous talent. Said company knows that you want its employees, and has made it pretty hard to pry people out of there. If you expand the aperture and look for someone who can do the job well tomorrow as well as today, you can find some gems, and you can offer them opportunities their current employer might not be able to. The engineer who wants to move into product management, but is blocked from leaving his team; the product manager who wants to get into sales, but there’s no open headcount. You can get great talent if you are willing to take a risk on people by challenging them to do new things. They will join you precisely because you are willing to take that risk. And those willing to take risks introduce the exact self-selection tendency you are looking for.

For example, if you’re hiring a software engineer and all your code is written in a certain language, that doesn’t necessarily mean you should hire an expert in that language. You should hire the best engineer you can find, regardless of her coding preference, because if she’s the best she can down enough Java to C how to make the Python Go.104 And when the language of choice changes (it inevitably will) she’ll be able to adapt better than anyone else. Supercomputer pioneer Seymour Cray used to deliberately hire for inexperience because it brought him people who “do not usually know what’s supposed to be impossible.”105 We do something similar at Google with our Associate Product Manager (APM) program, which was created by Marissa Mayer back when she was a director on Jonathan’s team with a prime directive of hiring the smartest computer scientists we could find straight out of school. This isn’t unusual; lots of companies hire smart recent graduates—that’s the easy part. The hard part is to give them vital roles in projects with real impact. Smart creatives thrive in these positions, while risk-averse managers cringe. They have no experience! (Good!) What if they screw up? (They will, but they will also succeed in ways you can’t imagine.) Brian Rakowski set the tone pretty well as our very first APM, hired straight out of Stanford and immediately given product management responsibility for Gmail, working directly with lead engineer Paul Buchheit. Brian is now a lead on the Android team, and Gmail hasn’t done too poorly either.

Of course, sometimes we screw this up ourselves. Once, Salar Kamangar was impressed with one of our young marketing associates and wanted to transfer said young man into the APM program. Unfortunately, the APM program only accepted candidates with degrees in computer science, which this associate didn’t have. Although Salar argued that the young associate was a self-taught programmer and had a “history of working closely with engineers and shipping things,” several influential execs, including Jonathan, steadfastly refused to expand the aperture, and denied the transfer. The young marketing associate, Kevin Systrom, eventually left Google. He cofounded a company called Instagram, which he later sold to Facebook for a billion dollars.106 You’re welcome, Kevin!

One way to make expanding the aperture work is to judge candidates based on trajectory. Our former colleague Jared Smith notes that the best people are often the ones whose careers are climbing, because when you project their path forward there is potential for great growth and achievement. There are plenty of strong, experienced people who have hit a plateau. With those candidates, you know exactly what you are getting (which is good) but there is much less potential for the extraordinary (bad). It’s important to note that age and trajectory are not correlated, and that there are exceptions to the trajectory guideline, such as people running their own business or those with nontraditional career paths.

Expanding the aperture is much harder as you work your way up the corporate food chain. Hiring senior people is almost always experience-based, and experience is important, but in most industries today technology has rendered the environment so dynamic that having the right experience is only a part of what it takes to succeed. Companies consistently overvalue relevant experience when judging senior candidates. They should be more focused on what talented smart creatives have to offer.

For example, in 2003, when we were looking for a head of human resources to round out our executive team, we interviewed something like fifty candidates, many with great experience in the traditional sense but none who were qualified to do what we knew needed to be done. We were growing a company faster than perhaps any other company in history, so all the standard operating experience that these candidates brought to the table was not going to cut it. We needed executives who understood how to build scalable engines on which a company could run at a fundamentally different pace.

It was a long process. At one point Eric blurted out, “Find me a Rhodes scholar who is also an astrophysicist.” We decided after some discussion that an astrophysicist, although probably qualified for the job, wouldn’t come to Google to be a business executive. “Alright,” Sergey said, “get me a law partner.” Jonathan found one of the law partner candidates in Sergey’s office one day, furiously writing a contract. Sergey had given him an assignment: Write a contract that is well done, comprehensive, and funny. A half hour later, the candidate delivered contract 666, whereby Mr. Sergey Brin sold his soul to the devil in exchange for one dollar and numerous other considerations. The piece was brilliant and funny but he didn’t get the job—not technical enough.

With the lawyer approach not working out, our search partner, Martha Josephson, suggested that the right combination might be McKinsey partner + Rhodes scholar, and brought us Shona Brown, whom we hired to run business operations even though she had never held a role like that before. It worked out so well that when we needed a new CFO in 2008 to replace the estimable George Reyes, Eric asked Martha to “find another Shona Brown.” She found Rhodes scholar and former McKinsey partner Patrick Pichette, who became CFO in 2008.

(Google’s preference for talented people goes well beyond senior execs. One year, Jonathan was heading out to our London office, where his agenda included speaking at an event with a group of Rhodes scholars that Shona was hosting. He was trying to determine how to decide which of them would receive offers to interview in Mountain View, when he ran into Sergey in a hallway and explained his problem. “Why decide at all?” Sergey said. “Offer all of them jobs.” Which seemed crazy at first, but not so crazy when he thought about it. Some of those Rhodes scholars went on to do very well at Google.)

Expanding the aperture brings risks. It leads to some failures, and the start-up costs for hiring a brilliant, inexperienced person are higher than those of hiring a less-brilliant, experienced one. The hiring manager may not want to bear the costs, but such concerns need to be set aside for the greater good. Hiring brilliant generalists is far better for the company.

Everyone knows someone great

You probably know someone whose résumé is truly exceptional: someone who climbed K2, is an Olympic-class hockey player, published a critically acclaimed novel, worked her way through college and finished cum laude, just had an art exhibit, started a (real) nonprofit, speaks four languages, owns three patents, codes top-100 apps for fun, plays lead guitar in a band, and once danced onstage with Bruno Mars. If you know at least one person like that, then it stands to reason that everyone you work with knows one of them too. Then why do you let only recruiters handle recruiting? If everyone knows someone great, why isn’t it everyone’s job to recruit that great person?

Establishing a successful hiring culture that delivers a steady stream of outstanding people starts with understanding the role of recruiters in sourcing candidates. Hint: It isn’t their exclusive realm. Don’t get us wrong, we love good recruiters. We work with them all the time and appreciate their insights and their hard work. But the job of finding people belongs to everyone, and this fact needs to be woven into the fabric of the company. Recruiters can manage the process, but everyone should be recruited into recruiting.

This is easy when a company is small, since getting all hands on the recruiting deck is natural. At a certain size, however—in our experience the number is around five hundred employees—managers start worrying about headcount allocation more than about whom they’re going to get to fill those allocations. You hear about “fighting for headcount” a lot more than “finding great people,” because the latter is what those recruiters are for, right? Not exactly. The problem with overdependence on recruiters is that it becomes tempting for recruiters to stop looking for the cream of the crop and settle for the half-and-half or even the skim milk. They don’t have to live with their mistakes, the company does. On the other hand, it is easy for any company to double in size with great people. All it takes, as Larry often told us, is for each employee to refer just one great person. When you completely delegate recruiting, quality degrades.

The simple way to keep recruiting in everyone’s job description is to measure it. Count referrals and interviews. Measure how quickly people fill out interview feedback forms. Encourage employees to help with recruiting events, and track how often they do. Then make these metrics count when it comes to performance reviews and promotions. Recruiting is everyone’s job, so grade it that way.

Interviewing is the most important skill

The loftier your hiring aspirations, the more challenging and important the interview process becomes. The interview is where you truly learn about a person—it is far more important than the résumé. The résumé tells you that the person got a 3.8 from an elite school while majoring in computer science and running track; the interview tells you that the person is a boring grind who hasn’t had an original idea in years.

The most important skill any business person can develop is interviewing. You’ve probably never read that in any management book or heard it in an MBA course. CEOs, professors, and venture capitalists always (correctly) preach the primacy of people when it comes to success, but they often don’t say how to get those great people. They talk in theory, but business is practice and in practice your job is to determine a candidate’s merit in the context of an artificial, time-constrained interview. That calls for a unique and difficult skill set, and the simple truth is most people are not good at it.

Go back to the initial response people had in our hypothetical “What is the most important thing you do at work?” exercise, which was “Go to meetings.” Meetings are indeed how we spend the majority of our time. The nice thing about meetings is that the higher up you are on the food chain, the less you have to prepare for them. When you’re the top dog (or somewhere up there on the canine hierarchy), other people prepare for the meeting while all you have to do is listen and opine. Your colleagues leave with the action items, and you leave with nothing to do but run to the next meeting.

Conducting a good interview requires something different: preparation. This is true regardless of whether you’re a senior executive or a fresh associate. Being a good interviewer requires understanding the role, reading the résumé, and—most important—considering your questions.

You should first do your own research on who the interviewee is and why they are important. Look at their résumé, do a Google search, find out what they worked on and do a search on that too. You aren’t looking for the drunken Carnival photo, but rather trying to form an opinion of them—is this someone who is interesting? Then, in the interview use your researched knowledge of their projects to dig deeper. You need to ask challenging questions that push the candidate. What was the low point in the project? Or why was it successful? You want to learn if the candidate was the hammer or the egg, someone who caused a change or went along with it.

Your objective is to find the limits of his capabilities, not have a polite conversation, but the interview shouldn’t be an overly stressful experience. The best interviews feel like intellectual discussions between friends (“What books are you reading right now?”). Questions should be large and complex, with a range of answers (to draw out the person’s thought process) that the interviewer can push back on (to see how the candidate stakes out and defends a position). It’s a good idea to reuse questions across candidates, so you can calibrate responses.

When asking about a candidate’s background, you want to ask questions that, rather than offering her a chance to regurgitate her experiences, allow her to express what insights she gained from them. Get her to show off her thinking, not just her résumé. “What surprised you about…?” is one good way to approach this, as it is just different enough to surprise a candidate, so you don’t get rehearsed responses, and forces her to think about her experiences from a slightly different perspective. “How did you pay for college?” is another good one, as is “If I were to look at the web history section of your browser, what would I learn about you that isn’t on your résumé?” Both of these can lead to a far better understanding of the candidate. They are also quite specific, which helps you gauge how well someone listens and parses questions.

Scenario questions are often helpful, but more so when interviewing more senior people, because they can reveal how a person will use or trust their own staff. For example, “When you are in a crisis, or need to make an important decision, how do you do it?” will often reveal if a candidate is of the “if you want something done, do it yourself” ilk, or if they will rely on the people around them. The former is more likely to get frustrated with the people who work for them and thus hang on to control, the latter more likely to hire great people and have faith in them. Generic answers to these questions indicate someone who lacks insight on issues. You want the answers to be interesting or at least specific. If the answers you get are cut and pasted from marketing claims, or are simply the reflection of commonly held wisdom, then you have a generic candidate, one who will not be adept at thinking deeply about things.

Then there are Google’s infamous brainteasers. In recent years, we have phased out the practice of asking these puzzling questions during interviews. Many of the questions (and answers) ended up online, so continuing to ask them wouldn’t necessarily reveal a candidate’s ability to reason out a complex problem as much as her ability to conduct research before an interview and then act as if she hadn’t memorized the answers to all of our brainteasers. (A valuable skill, to be sure; just not the one we’re looking for.) The brainteasers also became a lightning rod for criticism as an elitist tool. To those critics, let us say once and for all: You are right. We want to hire the best minds available, because we believe there is a big difference between people who are great and those who are good, and we will do everything we can to separate the two. And if you, our critics, still persist in believing that elitism in hiring is wrong, well, we have just one question for you: If you have twelve coins, one of which is counterfeit and a different weight than the others, and a balance, how do you identify the counterfeit coin in just three weighings?107

When preparing for an interview, it helps to keep in mind that the interviewee is not the only person being interviewed. A highly qualified candidate is evaluating you as much as you are evaluating her. If you waste the first few minutes of the interview reading her résumé and making small talk, the candidate who is considering several options (and the great candidates always have several options) may not be impressed. First impressions work both ways.

While you want to ask thoughtful questions, you should also identify the candidates who ask thoughtful questions. People who ask good questions are curious, smarter, more flexible and interesting, and understand that they don’t have all the answers—exactly the type of smart-creative characteristics you want.

The only way to get good at interviewing is to practice. That’s why we tell young people to take advantage of every opportunity to interview. Some of them do but most of them don’t, preferring to spend their time on things they think are more important. They don’t realize what a great gift we are giving them. Come on, we’re saying, you can practice the most important skill you can possibly develop, get paid for doing it, and since you will most likely not be the person’s manager, you won’t have to live with the consequences of a bad hire. They ignore us. Getting people to interview is like pulling teeth.

Of course, not everyone is good at interviewing, and people who don’t want to get good at it won’t. At Google we implemented a trusted-interviewer program, an elite team of people who were actually good at interviewing and liked to do it, and they got to do the bulk of the work (and were rewarded with higher scores during performance review). Product managers who wanted to be in the program had to go through interview training and shadow a minimum of four interviewers as they met with candidates. Once in the program they were scored on a variety of performance metrics, including how many interviews they conducted, reliability (it’s amazing how many people think it’s OK to cancel interviews at the last minute, or not even show up), and quality and promptness of their feedback (quality of feedback declines precipitously after forty-eight hours; our best interviewers schedule time to enter their feedback right after the interview). We published these stats and let people not in the program “challenge” the incumbents and replace them if their performance was better. In other words, not interviewing was seen as punishment. With this program, interviewing became a privilege, not a chore, and quality increased across the board.

And about that drunken Carnival photo: Unless they demonstrate a serious character flaw, we generally don’t hold a candidate’s online photos and commentary against her. We are hiring for passion, remember, and passionate people will often have an exuberant online presence. This demonstrates a love of the digital medium, an important characteristic in today’s world.

Schedule interviews for thirty minutes

Who decided that an interview should last an hour? Oftentimes, you walk into an interview and know within minutes that a person is wrong for the company and the job. Who says you have to spend the rest of the hour making useless conversation? What a waste of time. That’s why Google interviews are a half hour. Most interviews will result in a no-hire decision, so you want to invest less time in them, and most good interviewers can make that negative call in a half hour. If you like the candidate and want to keep talking, you can always schedule another interview or choose to make time in your calendar right then and there (easy to do if you have scheduled the following fifteen minutes to write up your feedback). The shorter interview time forces a conversation that’s more protein and less fat; there’s no time for small talk or meaningless questions. It forces people, including (especially!) you, into a substantive discussion.

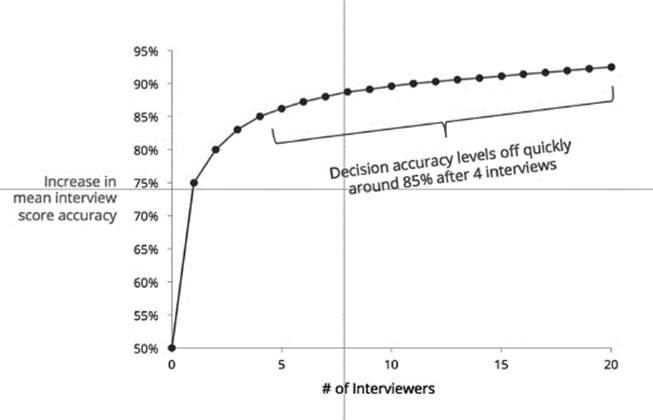

Not only do most companies conduct overlong interviews, they conduct too many of them. One time, in our early days at Google, we interviewed a particular candidate over thirty times and we still couldn’t decide if we wanted to hire him. That’s just wrong. So we declared by fiat that a candidate couldn’t be interviewed more than thirty times. Then we did some research and discovered that each additional interviewer after the fourth increased our “decision accuracy” by less than 1 percent. In other words, after four interviews the incremental cost of conducting additional interviews outweighs the value the additional feedback contributes to the ultimate hiring decision. So we lowered the maximum to five, a number with the added benefit (at least for computer scientists) of being prime.

Have an opinion

Remember: From the interviewer’s standpoint, the goal of the interview is to form an opinion. A strong opinion. A yes or no. At Google we grade interview candidates on a scale of 1 to 4. The average score falls around a 3, which translates to “I’ll be okay with this person getting an offer, but someone else should like them a lot.” As an average, 3 is fine, but as an individual response it’s a cop-out, since what it really means is that the interviewer can’t make up his mind and is passing the buck to someone else to decide. We encourage interviewers to take a stand. For example, on the product management team the score of 4.0 meant “This person is perfect for this role. If you don’t hire them, expect to hear from me.” This isn’t just saying we should hire the person. It’s saying, “If someone wants to get in the way of hiring this person, I will hunt you down and… passionately debate the decision based on the objective data included in the packet.”

The language assigned to these scores was deliberately emotional—“expect to hear from me”—because smart creatives care about who joins their team. It’s as if they are inviting someone into their family. They believe every interview must lead to a decision, and that decision is personal. There’s no wishy-washy.

When you tell people to have an opinion, though, you need to tell them what to have an opinion about. Whether or not to hire the candidate is obvious, but interviewers also need to be guided in how to form that opinion. At Google we break down candidate evaluations into four different categories, and we keep these categories consistent across functions. From sales to finance to engineering, smart creatives tend to score well on all of these, regardless of what they do or at what level. The categories and descriptions:

• Leadership: We’ll want to know how someone has flexed different muscles in various situations in order to mobilize a team. This can include asserting a leadership role at work or with an organization, or even helping a team succeed when they weren’t officially appointed as the leader.

• Role-Related Knowledge: We look for people who have a variety of strengths and passions, not just isolated skill sets. We also want to make sure that candidates have the experience and the background that will set them up for success in the role. For engineering candidates in particular, we check out coding skills and technical areas of expertise.

• General cognitive ability: We’re less concerned about grades and transcripts and more interested in how a candidate thinks. We’re likely to ask a candidate some role-related questions that provide insight into how they solve problems.

• Googleyness: We want to get a feel for what makes a candidate unique. We also want to make sure this is a place they’ll thrive, so we look for signs around their comfort with ambiguity, bias to action, and collaborative nature.

Friends don’t let friends hire (or promote) friends

Another part of the interviewing process that most companies screw up is letting the hiring manager make the hiring decision. The problem with this is that the hiring manager will probably be the new employee’s manager for only a matter of months or a year or two; organizations are highly fungible. Besides, in the most effective organizations, who you work for matters a lot less than who you work with. Hiring decisions are too important to be left in the hands of a manager who may or may not have a stake in the employee’s success a year later.

That’s why at Google we set up the process so that the hiring decision is made by committee. With hiring committees, it doesn’t matter who you are: If you want to hire someone, the decision needs approval from a hiring committee, whose decisions are based on data, not relationships or opinion. The primary criterion for serving on a hiring committee is that you will not be driven by anything other than what is best for the company, period. Committees should have enough members to allow a good range of viewpoints, but should be small enough to allow an efficient process; four or five is a pretty good number. The best composition promotes a wide variety of perspectives, so aim for diversity: in seniority, in skills and strengths (since people will often favor people cut in their own mold), and in background. The hiring manager is not entirely powerless in a committee-based process; she (or her recruiter) can participate in committee meetings, and she gets to decide whether or not to move a candidate from interview process to offer process, meaning she has veto power but not hiring power. The hiring committee ensures that people don’t hire their friends, unless those friends happen to be superstars.

In the early 2000s, as Google started adding employees by the thousands, Eric, Larry, and Sergey observed that many of the newer hires were good but not as strong as needed. Perhaps they couldn’t control what every group was doing, the trio decided, but they could control whom they hired. Larry suggested a policy that senior management would review every offer. The resulting hiring committee process, which was developed by Urs Hölzle, entails a hierarchy of committees, culminating with a committee of one: Larry, who for several years reviewed every offer. This made it clear to everyone involved in hiring just how high a priority it was to the company. The process was designed to optimize for quality, not efficiency, and for control, not scale. Over the years, we have done our best to make it scale efficiently anyway, but our original tenet still stands, even as we pass forty-five thousand employees: Nothing is more important than the quality of hiring.

The unit of currency in this system is the hiring packet, a document containing all the known information about a candidate who has progressed through the interview process. A hiring packet needs to be both comprehensive and standardized, so that all members of the hiring committee get the exact same information, and that information comprises a complete picture of the candidate. The Google hiring packet was designed by engineers with this objective in mind (as well as the objective of keeping Larry happy, since he reviewed each one getting an offer). It is based on a template that is standardized across the entire company (functions, countries, levels), with room for flexibility.

When completed, the ideal hiring packet is stuffed to the brim with data, not opinion, and this distinction is critical. If you are the hiring manager or one of the interviewers, it isn’t sufficient to express an opinion; you need to support it with data. You can’t say, “We should hire Jane because she’s smart.” You have to say, “We should hire Jane because she’s smart and has the MacArthur Fellowship to prove it.” Most candidates aren’t accommodating enough to win MacArthur Fellowships, so supporting every opinion with data or empirical observations tends to be a lot harder than this example. But when people don’t do it, packets get kicked out of the committee.

The other important rule is that the packet is the only source of information for the hiring committee. If something isn’t in the packet, it doesn’t get considered. This forces people to be thorough in constructing a hiring packet. You can’t omit information from the packet and then bring it up in the meeting as a power move; aces up the sleeve get people shot (figuratively… usually). The people who get hired are the ones with the best packets, not the loudest cheerleaders on the committee.

The best packets are like any other great piece of executive communications: a one-page summary with all the key facts, and comprehensive supporting material. The summary consists of hard data and evidence in support of the hiring decision, and the supporting material includes interview reports, résumé, compensation history, reference information (especially if the candidate was sourced via internal reference), and any other relevant material (college transcripts, copy of a candidate’s patents or awards, writing or coding samples).

In compiling a hiring packet, details matter. For example, for recent graduates, does their school’s GPA comply with a typical American four-point scale, or is it like the University of Geneva, which grades on a six-point scale? Class rank is another important detail for recent grads; because of grade inflation, an A may no longer be worth that much, but a top class ranking is still the best. The packet also needs to be well formatted and easy to read quickly; for example, the candidate’s best or worst answers should be highlighted for easy reference. But not everything should be formatted: A candidate’s original résumé should be included as is, so everyone can see the typos and formatting errors (or bold or italic fonts). Getting all of these details of the packet right is what enables the committee to get the details of the candidate right.

Even a purely data-based packet can lie, though. Interviewers have natural biases—one person’s 3.8 rating is another’s 2.9 (and another, more irrational person’s π). The solution to this? More data. Stipulate that all packets include statistics on each interviewer’s past scores—including number of interviews, range of scores, and mean—so committee members can factor into their decision-making which interviewers grade higher and which clump their scores in the middle of the bell curve. (Interviewers, knowing that this data is part of the packet, will often be more conscientious in grading tougher and providing more opinionated scores.)

Some managers want absolute control over building their teams. When we instituted the committee system, some people hated it and even threatened to leave. That’s OK. If someone cares that much about having absolute control over their team, perhaps you don’t want them around. Dictatorial tendencies rarely contain themselves to just one aspect of work. The good managers will realize that hiring by committee is actually better for the company as a whole.

Similarly, deciding who gets promoted should also be via a committee rather than a top-down management decision. Our managers can nominate their people for promotion and act as advocates throughout the process, but the decision itself is out of their hands. The reasons are the same as they are for hiring: Promotions have a company-wide impact, so they are too important to be left in the hands of individual managers. But with promotions, there is an additional factor favoring a committee-based process. Many smart creatives (a majority, in our experience) are conflict-averse and have a hard time saying no. With committees, the rejection doesn’t come from an individual but from the more faceless committee. This small detail can have a surprisingly big calming effect on promotion rates.

(There’s a lot more to how Google hires people than we can get into here. If you want to learn more and get the science behind not just recruiting but all of our people practices, read our colleague Laszlo Bock’s upcoming book, Work Rules! Laszlo runs people operations at Google, and in his book he details how the principles we established in the early days grew into a system that any team or business can emulate.)

Urgency of the role isn’t sufficiently important to compromise quality in hiring

Our emphasis on quality hiring does not mean the process has to be slow. In fact, everything that we’ve described about our method is set up to make it faster. We keep interviews at a half hour and limit ourselves to five per candidate. We tell interviewers that once they finish meeting with a candidate they should immediately tell the recruiter thumbs-up or -down. We design candidate packets so that the hiring committees making final decisions on candidates can review a packet within 120 seconds. (Literally. We timed it.) These steps make the hiring process scalable and force clarity. They’re good for candidates too, because piling on interviews and stringing out a decision is unfair. After all, if they’re the kind of people you want to hire, they want to move fast too.

But there is a golden rule to hiring that cannot be violated: The urgency of the role isn’t sufficiently important to compromise quality in hiring. In the inevitable showdown between speed and quality, quality must prevail.

Disproportionate rewards

Once you get your smart creatives on board, you need to pay them; exceptional people deserve exceptional pay. Here again we can look to the sports world for guidance: Outstanding athletes get paid outstanding amounts. It’s not uncommon for the best player on a professional team to be compensated with deals worth hundreds of millions, while the deal the rookie at the end of the bench gets is only in the hundreds of thousands. Are those stars worth it? Baseball great Babe Ruth, when asked if he thought it was right that his salary was higher than President Herbert Hoover’s, answered, “Why not? I had a better year than he did.” We have a more reasoned response. Yes, they are worth it (when they perform up to expectations), because successful athletes possess rare skills that are tremendously leverageable. When they do well, they have a disproportionate impact. They help teams win, and winning drives huge business benefits: more fans, more viewers, more jerseys and hats sold. Hence, the big money.

Smart creatives today may not share many characteristics with professional athletes, but they do share one important thing: the potential for disproportionate impact. Top performers get paid well in athletics, and they should in business too. If you want better performance from the best, celebrate and reward it disproportionately.

This doesn’t mean you should give new hires a blank check. In fact, the compensation curve should start low. You can attract the best smart creatives with factors beyond money: the great things they can do, the people they’ll work with, the responsibility and opportunities they’ll be given, the inspiring company culture and values, and yes, maybe even free food and happy dogs sitting desk-side. (One of the early engineers at Google wanted to bring his ferret to the office. We said yes. He didn’t haggle over salary.) But when those smart creatives become employees and start performing, pay them appropriately. The bigger the impact, the bigger the comp.

At the opposite end of the scale, managers should reward people greatly only when they do a great job. They are managing professionals, not coaching Little League, where everyone gets a standing ovation and a trophy, even the dreamer in right field who spends the game picking daisies and hunting for four-leaf clovers. All men and women are created equal in that they are all endowed with certain inalienable rights, but that decidedly does not mean they are all equally good at what they do. So don’t pay or promote them as if they are. The business world traditionally rewards people for being closer to the top (case in point: outrageous CEO salaries) or for being closer to the transactions (investment bankers, salespeople).108 But what’s most important in the Internet Century is product excellence, so it follows that big rewards should be given to the people who are closest to great products and innovations. This means that yes, the lower-level employee who helps create a breakthrough product or feature should be very handsomely rewarded. Pay outrageously good people outrageously well, regardless of their title or tenure. What counts is their impact.109

Trade the M&Ms, keep the raisins

You have done all this work to create a hiring process that brings in all these awesome smart creatives, and how do they pay you back? By leaving!! That’s right. News flash: When you hire great people, some of them may come to realize that there is a world beyond yours. This isn’t a bad thing, in fact it’s an inevitable by-product of a healthy, innovative team. Still, fight like hell to keep them.

The best way to retain smart creatives is to not let them get too comfortable, to always come up with ways to make their jobs interesting. When Georges Harik, who was part of the team that created AdSense and who helped solve the “ads suck” problem we discussed earlier in the book, was thinking about leaving the company, Eric suggested that he might be interested in sitting in on his staff meetings. So it came to be that Eric’s staff meetings included the founders, all the execs who reported to Eric… and Georges, who was also added to the staff’s email distribution list. Eric and the rest of the company’s leaders got more perspective from the engineering trenches, and Georges learned a lot about business. He was intrigued enough by what he heard that he ended up joining the product management team and stayed at the company for two more years. That’s two years of contribution from Georges we otherwise would not have gotten.

Jonathan employed the same approach when he was looking for help in managing his staff meetings. Typically, senior execs may bring in a chief of staff to play this role, but having a full-time chief of staff just encourages politics. Jonathan’s solution was to rotate a series of APMs through the job in six-month stints, serving as his de facto chief of staff and working directly for Jonathan while still holding down their day jobs. Other APMs were encouraged to sign up for so-called chain-gang tasks, which were side projects posted on an internal site for which anyone could volunteer. For example, one task, created in September 2003, was to help Larry Page learn more about how projects got done at Google. Maybe not the most exciting assignment, but several young APMs jumped at the chance to work with the company’s cofounder. The point of these assignments wasn’t to spice up our staff meetings or to take advantage of cheap labor, it was to make the lives of our talented employees more interesting and challenging.

But often it takes more than interesting side projects to keep people engaged and prevent them from leaving. You need to prioritize the interests of the highly valued individual over the constraints of the organization. Salar Kamangar, whom the founders hired straight out of Stanford, is a great example of this. Salar helped invent AdWords and spent several years in the product organization, but when he was ready to expand his responsibilities and become a general manager, we didn’t have a role for him. So we created one, appointing him the head of YouTube. There arenumerous other cases like this, where smart creatives need or want to do something new and the company figures out a way to make it happen. Do the best thing for the person and make the organization adjust.

Encouraging people to take on new roles can be institutionalized in the form of rotations, but it needs to be done properly or it will backfire. Google’s APM program (and its spin-offs in marketing and people operations) forces rotation every twelve months. This works great in a small program with entry-level employees, but it is difficult to create a structured rotation program across bigger segments of the company. So our approach has always been to encourage job movement, to make it as easy as possible, and to make it a standard part of the management discussion. We discuss it in our staff meetings and one-on-ones: Who on your team is a good candidate for rotation? Where do they want to go? Do you think that is the best thing for them?

Make sure as you have these discussions that the employees in question are the good ones. Managers are like kids trading goodies after a night of Halloween trick-or-treating: When you push them to rotate people off their teams, their inclination is to hang on to the Reese’s cups and M&Ms and get rid of the boxes of raisins. This may be good for them, but it’s bad for the company. It keeps the very best people, the ones you want to keep challenged and inspired, locked up on one team. When Eric let Georges Harik sit in on his staff meetings, he didn’t do it because Georges was a mediocre performer whom he was trying to improve, but rather because Georges was a superior performer he was trying to keep. Make managers trade away their M&Ms; let them keep their raisins.

If you love them, let them go (but only after taking these steps)

Even if you keep your best people challenged and engaged, some of them will still consider leaving for greener pastures. When that happens, focus your retention efforts on the stars, the leaders, and the innovators (not necessarily the same people), and do whatever it takes to keep them around. The loss of these people can have a big ripple effect, as they often inspire their followers to leave too. Because people seldom leave over compensation, the first step to keeping them is to listen. They want to be heard, to be relevant and valued.

In these conversations, the leader’s role is not to be the advocate of the organization (“Please stay!”) but the advocate of the smart creative who is thinking about leaving. Many employees, particularly the younger ones, tend to think in terms of shorter time frames (perhaps still attached to the rhythms of a school year). They can overreact when they hit a bump in the road, and relish the days when they could start each semester with a clean notebook and no grades yet recorded. Help them take a longer-term perspective. How could staying at the company ultimately position them for much greater success when they do decide to leave? Have they considered the financial ramifications of leaving? Do they have a clear financial plan and a good sense of what they might be leaving behind? Listen to why they want to leave, and help them find a way to perhaps recharge their dilithium crystals while sticking around. Then, if they want to continue the conversation, have a plan for how they can develop their career while staying. This demonstrates your commitment to their success, not just the company’s.

The best smart creatives often want to leave so they can go start something on their own. Don’t discourage this, but do ask them for their elevator pitch. (“Elevator pitch” is venture capital–speak for “you have thirty seconds to impress me with your business idea.”) What is your strategic foundation? What sort of culture do you envision? What would you tell me if I were a prospective investor? If they don’t give good answers, then they obviously aren’t ready to go. In that case, we usually advise them to stick around and continue to contribute at the company while they are working on their idea, and tell them that when they actually can convince us to invest, we’ll let them go with our best wishes (if not a check!). This is a hard-to-resist offer, and it has helped us retain numerous talented people.

Then there is the case when the valued smart creative has an attractive offer in hand from another company. Sometimes that person will negotiate with an either/or threat: “Either do this, or else I’m out of here.” When that happens, the game is usually already over, since someone who operates that way is not emotionally attached to the company anymore and is unlikely to rebuild that commitment. But if there is a bond still there and you want to make a counteroffer, do it very quickly—within an hour if possible. After that, the employee has started to settle into the new company in her mind.

And of course, if it truly is in the best interest of the person to go, then let her go. As Reid Hoffman, Jonathan’s former colleague at Apple and founding CEO of LinkedIn notes, “Just because a job ends, your relationship with your employee doesn’t have to.… The first thing you should do when a valuable employee tells you he is leaving is try to change his mind. The second is congratulate him on the new job and welcome him to your company’s alumni network.”110

We had one talented young product manager, Jessica Ewing, who helped us launch iGoogle (which let users customize the Google home page and was retired in 2013) and had a very bright future at the company. But she also had a burning desire to try her hand at writing. Think about your career trajectory, we advised. Think about those stock units you still have to vest. She did and left anyway. Jessica, we haven’t heard from you in a while! Why don’t you write?

Firing sucks

Not as much as getting fired, to be sure, but it’s still plenty bad. If you’ve ever had to do it, you know how difficult it is to pull some poor soul aside and tell him it’s not working out. Maybe the employee will see it coming and take it well; maybe he won’t and will start throwing things. And maybe he’ll use labor laws as silver bullets in a vindictive quest to make your life miserable. All the factors that make the right smart creatives great hires can make the wrong ones hell to fire: their intensity, their confidence, their fearlessness. So always keep in mind, from the outset, that the best way to avoid having to fire underperformers is not to hire them. This is why we would rather our hiring process generate more false negatives (people we should have hired but didn’t) than false positives (we shouldn’t have hired, but did).

Test yourself: If you could trade the bottom 10 percent of your team for new hires, would your organization improve? If so, then you need to look at the hiring process that yielded those low performers and see how you can improve it. Another test: Are there members of your team whom, if they told you they were leaving, you would not fight hard to keep? If there are employees you would let go, then perhaps you should.

One last note: There are some people who actually enjoy firing. Beware of them. Firing instills a culture of fear that will inevitably fail, and “I’ll just fire them” is an excuse for not investing the time to execute the hiring process well.

Google’s Hiring Dos and Don’ts

Hire people who are smarter and more knowledgeable than you are.

Don’t hire people you can’t learn from or be challenged by.

Hire people who will add value to the product and our culture.

Don’t hire people who won’t contribute well to both.

Hire people who will get things done.

Don’t hire people who just think about problems.

Hire people who are enthusiastic, self-motivated, and passionate.

Don’t hire people who just want a job.

Hire people who inspire and work well with others.

Don’t hire people who prefer to work alone.

Hire people who will grow with your team and with the company.

Don’t hire people with narrow skill sets or interests.

Hire people who are well rounded, with unique interests and talents.

Don’t hire people who only live to work.

Hire people who are ethical and who communicate openly.

Don’t hire people who are political or manipulative.

Hire only when you’ve found a great candidate.

Don’t settle for anything less.

Career—Choose the F-16

We are frequently asked for career advice. Budding entrepreneurs, Nooglers fresh out of school, emerging superstars—they all want to know what they should do to manage their path. And if we are ever fortunate enough to be invited to give another graduation speech, say at one of our alma maters (are you paying attention, Princeton and Claremont McKenna?), it might sound something like this:

Treat your career like you are surfing

When Jonathan was in business school and interested in product management, he went to a couple of presentations given by prospective employers. One was from a company that was a leader in consumer packaged goods, stuff like shampoo and household cleaners. They described product management in their business as a science, driven by precise data garnered from focus groups and product performance. “It’s like driving forward by looking in your rearview mirror,” they said, and they meant that as a good thing.

Then he went to a presentation by one of the leading high-tech firms in Silicon Valley. They said that product management in Silicon Valley was like “flying an F-16 at Mach 2 over a boulder-strewn landscape, two meters off the ground. Plus, if you crash it’s just like a video game at the arcade, and we have lots of quarters.” Cool! The best industries are the ones where you’re flying the F-16, your pocket full of quarters, trying not to crash.

In business, and particularly in high tech, it’s not enough to be great at what you do, you have to catch at least one really big wave and ride it all the way in to shore. When people are right out of school, they tend to prioritize company first, then job, then industry. But at this point in their career that is exactly the wrong order. The right industry is paramount, because while you will likely switch companies several times in your career, it is much harder to switch industries. Think of the industry as the place you surf (in Northern California the most rad waves are at Mavericks, dude) and the company as the wave you catch. You always want to be in the place with the biggest and best waves.

If you choose the wrong company or you have bad luck with an aggro boss who drops in on your first wave, you’ll still have a killer time if you’re surfing in an industry with bodacious waves. (Alright, Mr. Spicoli, that’s enough surfer lingo.) Conversely, if you choose the wrong industry early in your career, then growth opportunities within your company will be limited. Your boss won’t move, and you’ll be stuck without much leverage when you’re ready to look for jobs at other companies.

Fortunately, the tectonic forces driving the Internet Century mean that a lot of industries are great places to surf. It’s not just the Internet companies that have a big upside, but also energy, pharmaceuticals, high-tech manufacturing, advertising, media, entertainment, and consumer electronics. The most interesting industries are those where product cycle times are accelerating, because this creates more chances for disruption and so more opportunities for fresh talent. But even businesses like energy and pharmaceuticals, where product cycle times are long, are ripe for massive transformation and opportunity.

From a compensation standpoint, stock options and other forms of equity are quite limited early in your career, so it’s more lucrative to develop expertise in the right industry than to bet on a particular company. Later, as you gain experience (and age!), it becomes more important to pick the right wave. At that point you can start to earn compensation packages with much more equity, so the priority flips.

Always listen for those who get technology

After you pick the industry, then it’s time to pick the company. When you do, listen for the people who truly get technology. These are the genius-level smart creatives who see, before the rest of us, where technology is going and how it will transform industries. Bill Gates and Paul Allen saw that chips and computers were getting cheap and that software would be the key to the future of computing, so they started Microsoft. Chad Hurley saw that cheap video cameras, bandwidth, and storage would transform how video entertainment is created and consumed, so he cofounded YouTube. Reid Hoffman knew that the connecting power of the web would be vital to professionals, so he started LinkedIn. Marc Benioff believed that powerful software would live in the cloud, so he based Salesforce.com on that principle and didn’t waver during the dot-com meltdown. Steve Jobs foresaw computers as consumer accessories and it took over two decades for the technology and market to catch up to him.

How do you know if someone gets it? It helps to look at their history. Often, they are playing with technology and entrepreneurship long before they think of it as a career. Reid Hoffman got his first job (at age twelve) by presenting a copy of a computer game’s manual marked up with his suggestions for product improvements to one of the game’s developers.111 He wasn’t looking for a job—he wanted to make the game better. Marc Benioff sold his first computer program (“How To Juggle”) and started a company making games for the Atari 800 when he was fifteen. Larry Page built a printer out of Legos. (It was dot matrix, but still.)

These are the famous examples, but there are many others, people who may not be as well known but brim with insights. They are the ones navigating the best waves in the best places. Find them, hook in, and hang on.

Plan your career

Career development takes effort and forethought—you need to plan it. This is such an obvious point, yet it’s astonishing how many people who have come to us over the years have failed to do it. Jonathan usually gives these folks a set of career exercises, accompanied with his favorite Tom Lehrer line—“Life is like a sewer: What you get out of it depends on what you put into it”112—and a promise that if they put real effort into the exercises, he will help them.

Here are some simple steps to creating a plan: