How Google Works

Communications—Be a Damn Good Router

At one point early in his career at Google, Jonathan was in a conversation with one of our engineers, who wondered about Jonathan’s propensity to respond to emails immediately and route his replies to so many Googlers. The engineer was frustrated with what he saw as Jonathan’s misplaced priorities—obviously someone so responsive to email and so prolific at spreading information must not be busy enough. So he told Jonathan, in a fit of pique, “You’re just an expensive router!” This was meant as an insult, since a router is a fairly basic networking device whose main job is to move packets of data from one point to another. Jonathan took the barb as a compliment.

Here’s a way to think about corporate communications: Picture a twenty-story building. You are on a middle floor, say the tenth, standing on a balcony. The number of people on each floor decreases as you go up. The top floor is occupied by just one person, while the bottom floor, aka the “entry level,” has hordes of people. Now imagine you are standing out on a balcony when the person above you—let’s call her your “boss”—yells something and drops a few documents. You catch them, being careful not to let them flutter away in the wind, and take them back inside to read. There’s some good stuff in there, and you carefully parse out a few bits that you think the people on the ninth floor should see, given the carefully pre-scripted boundaries of their jobs. So you go back out to the balcony and drop a sheet here and a paragraph there to your team below, who consume them as if they were the proverbial cold waters to a thirsty soul.136 When they’re done, they turn around and perform their own parsing ritual for the benefit of the thirsty people on eight. Meanwhile, up on eleven, your boss is starting the process all over again. And up on twenty… well, who knows what that guy’s doing.

This is the traditional model of information flow in most companies. The upper echelons of management gather information and carefully decide which bits to distribute to those that toil beneath them. In this world, information is hoarded as a means of control and power. As the leadership scholars James O’Toole and Warren Bennis note, many businesspeople who rise to positions of power often get there “not for their demonstrated teamwork but for their ability to compete successfully against their colleagues in the executive suite, which only encourages the hoarding of information.”137 We are reminded of the Communist apparatchiks of the Soviet Union, who kept all office copiers behind double-locked, steel-plated doors lest someone use the wonders of xerography to create an unauthorized copy of the five-year plan for grain production.138Most managers still think like those Soviet-era bureaucrats: Their job is to parse information and distribute it sparingly, because obviously you can’t trust those young rabble-rousers on the lower floors with the information keys to the company’s kingdom.

But the Soviet Union collapsed, and while such a parsimonious approach to spreading information may have been successful when people were hired to work, in the Internet Century you hire people to think. When Jonathan was in business school, one of his finance professors used to say that “money is the lifeblood of any company.” This is only partially true. In the Internet Century money is obviously critical, but information is the true lifeblood of the business. Attracting smart creatives and leading them to do amazing things is the key to building a twenty-first-century business, but none of that happens if they aren’t flush with information.

The most effective leaders today don’t hoard information, they share it. (Bill Gates in 1999: “Power comes not from knowledge kept but from knowledge shared. A company’s values and reward system should reflect that idea.”)139 Leadership’s purpose is to optimize the flow of information throughout the company, all the time, every day. This is an entirely different skill set.

As Jonathan told that engineer on that day several years ago, “If all I am is a very expensive router, I intend to be a damn good one.” What does that entail? Default to open, set challenging public goals and regularly fail to achieve them, and when in doubt, talk about your travels.

Default to open

Your default mode should be to share everything. Case in point: the Google board report. When Eric was CEO, he started a process that continues today. Every quarter the team creates an in-depth report on the state of the business, to be presented to the board. There is a written section—the board letter—which is crammed with data and insights on the business and the products, and slides with data and charts that the product leads (the senior executives in charge of the various product areas, including Search, Ads, YouTube, Android, and so on) use to guide the board meeting. Not surprisingly, much of this information is not for public consumption. But after the board meeting we do something that is surprising. We take the material that we presented to our board and share it with all of our employees. Eric presents the slides—the exact same slides that were presented to the board—to a company-wide meeting, and the entire board letter goes out in a Google-wide email.

Fine, Mr. Technicality, not the entire letter. Since it contains some data that shouldn’t be shared with everyone for legal reasons, we need to send the lawyers, along with a few communications folks, traipsing through the text to find and redact the legal landmines. This is where the “share everything” rubber hits the “but you can’t possibly mean everything, can you?” road. Every quarter, well-meaning and otherwise Googley Googlers highlight sentences and paragraphs with the red marker of death (digitally, of course—no paper was inked in the evisceration of this letter). “We can’t put that in the letter,” they say. “What if it leaks? It would cause problems.” Or “We can’t tell employees this, even though it’s true and it’s what we told the board. It might hurt morale.”

Fortunately, the people running this process understand that “share everything” doesn’t mean “share everything that wouldn’t look bad if it leaked and that doesn’t hurt anyone’s feelings,” it means “share everything except for the very few things that are prohibited by law or regulation.” Big difference! This is why we make everyone who wants something to be removed justify exactly why it needs to come out, and the reason better be very good. We have shared our board letter every quarter since the company went public in 2004, and leaks have not been a problem. Meanwhile, nobody complains that they don’t know what’s going on across the company. Or if they do, we tell them to read the board letter and watch Eric’s presentation. And there is an ancillary benefit to sharing the board materials: quality. While people will do a good job in preparing something for the board’s consumption, they will do a great job if they know that material will be shared with the entire company.

Defaulting to open doesn’t just cover board communications. We try to share virtually everything. The company’s intranet, Moma, includes information on just about every upcoming product, for example, and the weekly TGIF meeting usually features presentations by product teams of coming attractions, complete with demos and screenshots of cool things that are under development. Attending TGIF would be like scoring a Willy Wonka golden ticket for those legions of bloggers who love to speculate on what Google will be up to next, because we put it all out there, sharing stuff that in most companies would stay carefully hidden. Again, no grainy photos of screenshots or herky-jerky videos of demos are leaked, furtively captured from the back row. We trust our employees with all sorts of vital information, and they honor that trust.140

OKRs are another great example of transparency. These are an individual’s Objectives (the strategic goals to accomplish) and Key Results (the way in which progress toward that goal is measured). Every employee updates and posts his OKRs company-wide every quarter, making it easy for anyone to quickly find anyone else’s priorities. When you meet someone at Google and want to learn more about what they do, you go on Moma and read their OKRs. This isn’t just a job title and description of the role, it’s their first-person account of the stuff they are working on and care about. It’s the fastest way to figure out what motivates them.

Of course, this starts at the top. Every quarter at Google, Larry—like Eric before him—posts his OKRs and hosts a company-wide meeting to discuss them. All the various product and business leads join him onstage to talk through each OKR and what it means for their teams, and to grade themselves on how they performed against the previous quarter’s OKRs. This isn’t for show—the OKRs are real objectives, hammered out between the various product leaders at the outset of each quarter, and the grades of the previous quarter’s OKRs are usually full of red and yellow marks. The top leaders of the company candidly discuss where they failed and why. (At your company, does the top brass stand up each quarter and talk about the ambitious goals that they didn’t achieve?) After this meeting, when people go off to create their own OKRs, they have no doubt what the company priorities are for the quarter. This helps maintain alignment across teams even as the organization scales tremendously.

Know the details

John Seely Brown, the former director of Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center, once said, “The essence of being human involves asking questions, not answering them.”141 Eric likes to put this concept to the test when he walks the halls of Google or of the other companies with which he’s involved. When he runs into an exec he hasn’t seen in a while, the pleasantries don’t last long. After a cordial hello he’ll get to the point: “What’s going on in your job? What issues do you have? Tell me about that deliverable you owe me.” This has a couple of results: It helps Eric keep on top of the details of his business, and it helps him know which of his executives are on top of the details of their business. If someone is in charge of a business and can’t rattle off the key issues she faces in a matter of ten seconds, then she’s not up to the job. A hands-off approach to leadership doesn’t cut it anymore. You need to know the details.

Eric tends to remember everything and knows the deliverables people owe him, so the approach works well for him. Jonathan’s not quite in Eric’s league memory-wise, so he keeps the things that people owe him in the notes field of their contact on his phone. Then, if he runs into that person, he takes a moment and brings up the list, so he can query them on their progress.

Even when you ask the right questions, the true details can be hard to get. One day early in Eric’s tenure at Google, Larry and Sergey were upset about some problems in engineering and how some of the leaders were handling them. Eric listened to them talk about it for a while, then interjected, “Well, I’ve talked to them, and I’ll tell you what they are doing.” He then went on to describe what he believed was happening with that particular team.

Larry listened for a few sentences and then interrupted. “That’s not what they’re doing. Here’s what they’re doing.” Larry listed some things and Eric quickly realized that Larry was right. Eric had details, but Larry had the truth. The forest always trumps the trees.

How had this happened? Eric was listening to the managers, who were doing their old-school best to control the flow of information upward (the regurgitation and parsing technique works both ways, as any red-blooded middle manager worth his weight in plausible deniability knows full well). But Larry was listening to the engineers—not directly but via a smart little tool he had implemented called “snippets.” Snippets are like weekly status reports that cover a person’s most important activities for a week, but in a short, pithy format, so they can be written in just a few minutes or compiled (in a doc or draft email) as the week goes on. There is no set format, but a good set of snippets includes the most important activities and achievements of the week and quickly conveys what the person is working on right now, from cryptic (“SMB Framework,” “10% list”) to mundane (“completed quarterly performance reviews,” “started family vacation”). Like OKRs, they are shared with everyone. Snippets are posted on Moma, where anyone can see anyone else’s, and for years Larry received a weekly compendium of the snippets from engineering and product leads. That way he always could get at the truth.

Speaking of which…

It must be safe to tell the truth

Jonathan once took a history class in college that he knew was a favorite of the school’s football players. When the time came to present his research project for the semester, he remembered that the kids in the class, most of whom actually knew something about history, had been challenged by the instructor to ask difficult questions of their peers, not out of spite but to boost the class-participation portion of their grade. Jonathan did not relish the idea of standing before a bunch of grade-hungry history majors intent on skewering a wayward econ geek, so he devised a plan. He wrote his own questions and distributed them to the football players, who were also eager to improve their class-participation score. The quarterbacks and safeties lobbed their softballs, Jonathan knocked them out of the park, and everyone went home happy (except for you English majors cringing at our mixed sports metaphor).

Sometimes it seems like Jonathan’s questionable techniques have found their way to the business world. People are afraid to ask their leaders the tough questions, so they serve up softballs instead. This doesn’t just apply to questions. It is one of the most universal of human truths: No one wants to be the bearer of bad news. Yet as a leader it is precisely the bad news that you most need to hear. Good news will be just as good tomorrow, but bad news will be worse. That’s why you must make it safe to ask the tough questions and to tell the truth at all times, even when the truth hurts. When you learn of something going off the rails, and the news is delivered in a timely, forthright fashion, this means—in its own, screwed-up way—that the process is working. Canaries are dying in the coal mine, but at least you are aware of the avian carnage and the poor guy who brought their sad yellow corpses up into the light knows he won’t be thrown back down the shaft.

There are a few things we can recommend to make it easier to speak bad truth to power. After a product or key feature launches, we ask teams to conduct “postmortem” sessions where everyone gets together to discuss what went right and what went wrong. We then post the findings for everyone to see. The most important result of all these postmortems is the process itself. Never skip a chance to promote open, transparent, honest communications.

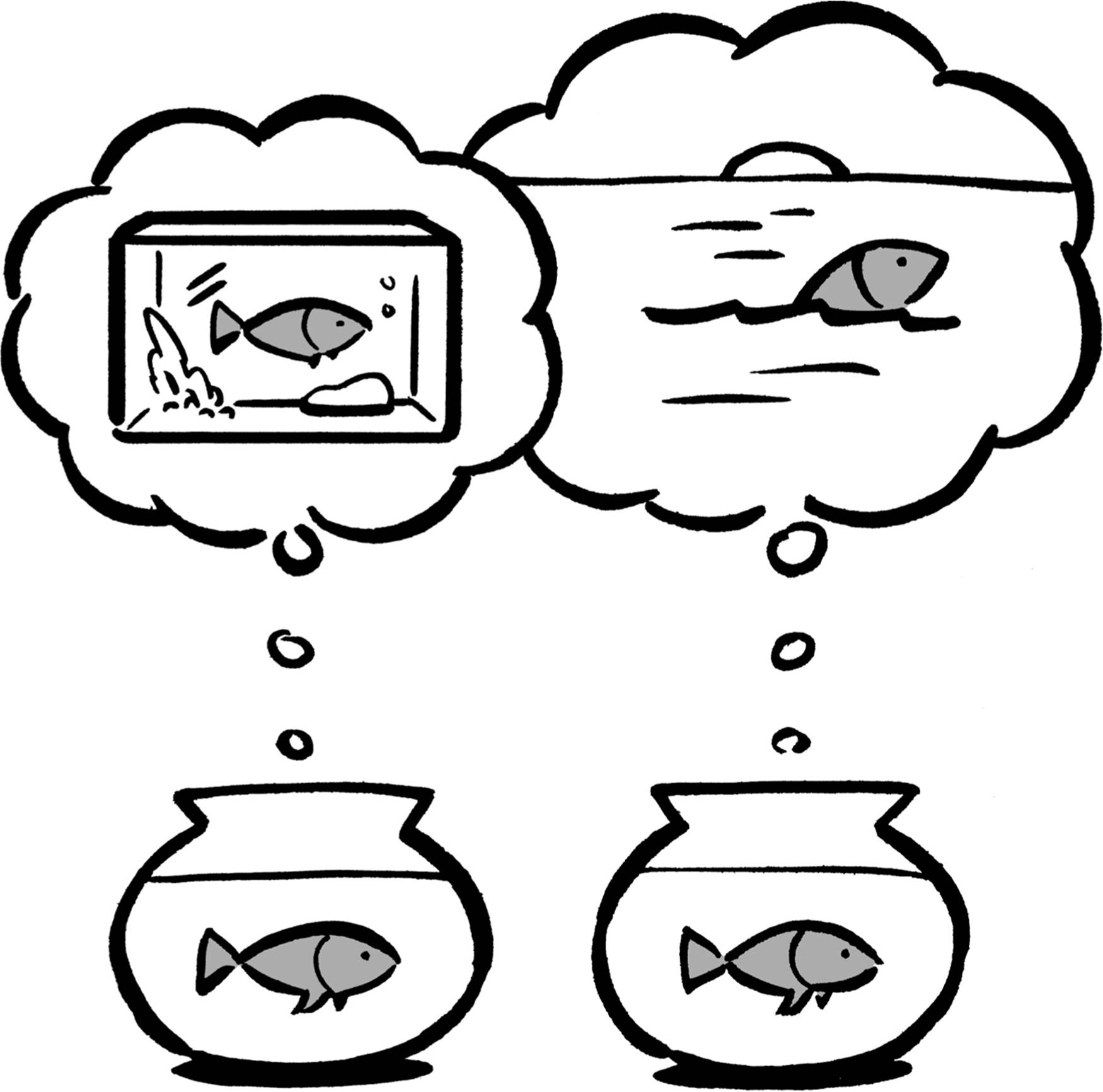

Another example is TGIF. The weekly company-wide meeting that Larry and Sergey host has always featured a no-holds-barred Q&A session, but as the company grew, this got harder and harder to manage. So we developed a system called Dory. People who can’t (or don’t want to) ask a question in person can submit it to Dory (named after the memory-challenged fish in Finding Nemo, though, like Dory herself, we can’t recall why), and when they do, others get to vote on whether it’s a good question or not. The more thumbs-up votes a question receives, the higher it goes in the queue, and the tougher questions tend to get a lot of thumbs-up. At TGIF the Dory queue is put on the screen, so as Larry and Sergey go through the questions they can’t cherry-pick which ones they want to answer. They just go down the list, top to bottom, tough questions and easy. Dory lets anyone directly ask the CEO and his team the toughest questions, while the crowdsourcing aspect of it keeps the lame questions to a minimum. Lame answers, on the other hand, are judged in a much lower-tech fashion: TGIF attendees are equipped with red and green paddles and encouraged to wave the red paddles if they don’t feel the questions are fully addressed.142

Eric calls our approach to transparency a “climb, confess, comply” model. Pilots learn that when they get in trouble, the first step is to climb: Get yourself out of danger. Then, confess: Talk to the tower and explain that you screwed up and how. Finally, comply: When traffic controllers tell you how to do it better next time, do it! So in your venture, when someone comes to you with bad news or a problem, they are in climb, confess, and comply mode. They have spent a lot of time considering the situation, and you need to reward their transparency by listening, helping, and having the confidence that next time around they will nail the landing.

Start the conversation

When the Michael Jackson concert movie, This Is It, was first released in October 2009, Jonathan got an idea. Google’s main campus in Mountain View is right next to a multiscreen movie theater, so Jonathan bought a bunch of tickets for the day of the premiere and invited the product team to select a viewing time and go. Hundreds of colleagues took him up on the offer. Teams organized outings to see the “King of Pop” at work on what was to be his comeback concert series, before his tragic death wrecked those plans.

Jonathan got some criticism from friends and coworkers—was it really worth the cost and lost productivity just so a bunch of Googlers could go see a movie? The answer was a resounding yes. The movie showed a world-class smart creative pushing his team and himself to be great by paying attention to every detail and always taking the concert audience’s point of view. But the more subtle objective of the Michael Jackson outing was that it was a way to start conversations. For months afterward, members of Jonathan’s team, from senior leaders to associates right out of college, would stop him by the espresso machine or in the café to thank him for the movie. Jonathan usually asked what they liked about it, and the conversation always took off from there.

Conversation is still the most important and valuable form of communication, but technology and the pace of work often conspire to make it one of the rarest. We are all connected 24/7, anywhere in the world, which is awesome but also tempting: How often have you emailed, chatted, or texted someone who was sitting only a few feet away? Yeah, too often; us too. Sociologists have a name for this phenomenon (as do anthropologists and mixologists): laziness. But in all fairness to tech-happy smart creatives, there is another factor at work, especially at big companies and especially for people who are newer to the company. As much as top executives and other company bigwigs may profess to be willing to talk, the open door works only when people walk through it. It can be hard for people who don’t know the organization to start that conversation. As a leader, you need to help them.

Some of our best leaders have taken unusual steps to facilitate. Urs Hölzle wrote and published a “user manual”… about himself. Anyone on his team (which numbers a few thousand) can read the manual and understand the best way to approach him, and how to fix him if he breaks.143Marissa Mayer held regular office hours—another cultural characteristic of early Google inspired by academia. Like a university professor, she set aside a few hours per week where anyone could come and talk to her. People signed up on a whiteboard outside her office (which she shared with a couple of other Googlers who usually decamped to other locations during her office hours), and on Wednesday afternoons the nearby couches were full of young product managers with some question or other to discuss.

Most every company has “tribal elders” who possess unique expertise in their field and a deep knowledge of the organization. Some of them are well known within the company, but others may not be, and one of the biggest favors a leader can do for a new smart creative is to connect her with them. At Bell Labs, these savants were often called “the guys who wrote the book,” because they had written a definitive book or article on the topic, and new employees were often directed by their supervisors to seek them out.144 At many companies (universities too), the incorrect, knee-jerk management reaction is to discourage employees from connecting with company rock stars. After all, they might waste their time with stupid questions, right? Yes, that does happen, but it turns out that most rock stars have very little patience for people wasting their time and they make doing so a very unpleasant experience. The inexperienced smart creative who does it once quickly learns not to do it again.

Repetition doesn’t spoil the prayer

In most aspects of life, you need to say something about twenty times before it truly starts to sink in.145 Say it a few times, people are too busy to even notice. A few more times, they start to become aware of a vague buzzing in their ear. By the time you’ve repeated it fifteen to twenty timesyou may be completely sick of it, but that’s about the time people are starting to get it. So as a leader you want to habitually overcommunicate. As Eric likes to say, “Repetition doesn’t spoil the prayer,” an axiom any Hail Mary–dispensing priest would second (or third, or fiftieth).

But there’s a right way to overcommunicate and a wrong way. In the Internet Century, the typical method, especially given the ease of the technology, is to share more stuff with more people. See an interesting article? Cut and paste the link into an email and send it to anyone who may be remotely interested. Yay! You’ve overcommunicated! You’ve also wasted hours of people’s time. Overcommunication done wrong leads to a careless proliferation of useless information, an avalanche of drivel piling into already overwhelmed inboxes.

Here are a few of our basic guidelines for overcommunicating well:

1. Does the communication reinforce core themes that you want everyone to get?

To get this right, you first need to know what the core themes are. When we say repetition doesn’t spoil the prayer, these are the prayers we are talking about. They are the things you want everyone to grasp; they should be sacred; and there should be only a few of them, all related to your mission, values, strategy, and industry. At Google, our themes include putting users first, thinking big, and not being afraid to fail. Also, we are all technology optimists: We believe technology and the Internet have the power to change the world for the better.

By the way, if you repeat something twenty times and people don’t get it, then the problem is with the theme, not the communications. If you stand up at your company’s all-hands meeting every week and reiterate your strategy and plan, and people still don’t understand or believe in it, then it’s the plan that’s flawed, not the method of delivering it.

2. Is the communication effective?

To get this right, you need to have something fresh to say. When we say repetition doesn’t spoil the prayer, we don’t quite mean it literally. This isn’t the Pledge of Allegiance, to be pounded verbatim into schoolchildren’s heads until the words are branded on the brain and the meaning has evaporated. Sometimes the presentation of the idea has to be varied to grab (or re-grab) attention. For example, Eric’s periodic memos to Googlers almost always made the point to focus on the user. To make it fresh, in one of his notes Eric pointed out that users are getting more sophisticated, as proven by the fact that search query length was increasing nearly 5 percent annually. This was a new and interesting stat that most Googlers didn’t know. It took a venerable theme and made it relevant.

3. Is the communication interesting, fun, or inspirational?

Most management teams are not curious—they are focused on doing the job at hand and tend to keep their communications equally businesslike. Smart creatives, though, have a wide array of interests. So if you come across an article that is insightful or interesting, and somehow relates to a core theme you have been communicating, go ahead and share it. Make it relevant to the team by picking a highlight or arguing a point. People will like it when you take off the blinders and talk about a wider variety of things. They want to be curious. A few years ago Jonathan spotted an article by journalist and founding Wired editor Kevin Kelly called Was Moore’s Law Inevitable?,146 which explored the history of Moore’s Law and predicted that its next iteration was inevitable. He sent a link to the article to his team with a short summary and a couple of simple questions: Do you think the next iteration of Moore’s Law is inevitable? How much longer before the current one runs its course? Given Kelly’s conclusions, is there anything Google should do differently? The email kicked off a spirited debate—a conversation!—that lasted a week. The subject of the future of Moore’s Law had no direct bearing on our business or on the jobs of the people who got involved in the discussion, but it was consistent with Google’s broader strategy to bet on the future of technology.

4. Is the communication authentic?

If it has your name on it, it should have your thoughts in it. Effective communication cannot be 100 percent outsourced. Yes, you can have people help you make the words pretty, but the thoughts, ideas, and experiences need to be yours. The more authentic the better.

When Eric toured Iraq in late 2009, he wrote a short, thoughtful analysis of his trip, with his observations about what was and wasn’t working there. His note had nothing to do with our employees as Googlers, but it had everything to do with them as citizens of the world, and it quickly circulated throughout the company. On a much lighter note, Jonathan often entertained his team with video clips of his daughter’s stellar exploits on the soccer field. Whether you are traveling to war zones or bursting with parental pride, don’t be afraid to tell your story!

5. Is the communication going to the right people?

The problem with email is that it’s too easy to add recipients. Not sure if someone should get something? What the hell, add them! Or better yet, just send it to the team distribution list. But a good communication goes only to the people who will find it useful. Choosing this list takes time, but the investment of a few seconds can have a big payoff. When you avoid distribution lists and instead actually pick the right people for the note, they are more likely to read it. Think about it from the other end: Which email are you more likely to read, the note to a distribution list or the one to you? It’s like the difference between junk mail and a hand-addressed card.

6. Are you using the right media?

Say yes to all forms of communication. People assimilate information in all sorts of ways, so what works for some people won’t work for others. If the message is important, use all the tools at your disposal to get it across: email, video, social networks, meetings and video conferences, even flyers or posters taped to the wall in the kitchen or café. Learn which methods work to connect with your colleagues, and then use them.

7. Tell the truth, be humble, and bank goodwill for a rainy day.

Smart creatives don’t have to work for you; they have plenty of options. Setting a constant tone of truth and humility creates a store of goodwill and loyalty among the team. Then, when you screw up, communicate that story with truth and humility too. You may draw down that balance of goodwill, but not completely.

How was London?

Most businesspeople go to staff meetings. You have probably lived through hundreds of them, so you already know what their agenda is: Receive status updates, conduct administrivia, nap with eyes open, check email surreptitiously under the table, wonder what mistakes in life were made to warrant this torture. The problem with the typical staff meeting is that it is organized around functional updates, rather than around the key issues facing the team, so you may end up spending too much time on things that don’t matter (do you really need a weekly update on everything?) and not enough on things that do. This structure also reinforces the organizational boxes around people—Pam is in quality control, Jason is the sales guy—rather than creating a forum where everyone has a stake in the key issues of the day.

One simple tactic to break the staff meeting monotony is the humble trip report. When people travel, ask them to put together a “What I Did on My Summer Vacation”–style report on what they did and what they learned. Then start all staff meetings with trip reports. (If no one traveled that week, then ask someone to do a weekend report instead.) The trip report makes the staff meeting more interesting. It inspires conversation, and when a person knows he is expected to present the trip report at the staff meeting, he’ll do a better job of it. Also because the well-done trip report gets people out of their functional rut, which is exactly what helps make a staff meeting successful. No matter what a person’s job is, they should be encouraged to have opinions about the business, industry, customers and partners, and different cultures.

Not long after he joined Google in 2008, CFO Patrick Pichette visited our office in London. When he returned, Eric opened his staff meeting by asking Patrick to talk about his trip. After saying how great the office was and whom he met with and blah blah blah, Patrick veered onto a completely different tangent. While in London, he had walked into every mobile phone store he saw and talked to the salespeople about the different phones and plans. So in his trip report he gave the executive team at Google an impromptu update on how our new mobile operating system, Android, and our slew of mobile apps were doing at the ground level. This had nothing to do with finance—Patrick didn’t assume he could offer observations only within his own jurisdiction—and it set the expectation that anyone could and should have insights across the entire business.

Review yourself

One of Eric’s most basic rules is sort of a golden rule for management: Make sure you would work for yourself. If you are so bad as a manager that you as a worker would hate working for you, then you have some work to do. The best tool we have found for this is the self-review: At least once per year, write a review of your own performance, then read it and see if you would work for you. And then, share it with the people who do in fact work for you. This will elicit greater insights than the standard 360-degree review process, because when you are initiating criticism of yourself it gives others the freedom to be more honest.

We mentioned Eric’s self-review from 2002 earlier in the book, when we were talking about Bill Campbell and how Eric initially (and incorrectly) believed he didn’t need a coach. There are other passages from that review where Eric candidly admitted his failings to his staff. For example: “I should have empowered the team earlier and forced more decisions down into the organization.” And: “I should have been more forceful to force closure on certain decisions and be impatient. I have tended to value the development of consensus more than I should in some situations.” These critiques were very well received by Eric’s team, because they showed a CEO who was as interested in improving as they were.

Email wisdom

Communication in the Internet Century usually means using email, and email, despite being remarkably useful and powerful, often inspires momentous dread in otherwise optimistic, happy humans. Here are our personal rules for mitigating that sense of foreboding:

1. Respond quickly. There are people who can be relied upon to respond promptly to emails, and those who can’t. Strive to be one of the former. Most of the best—and busiest—people we know act quickly on their emails, not just to us or to a select few senders, but to everyone. Being responsive sets up a positive communications feedback loop whereby your team and colleagues will be more likely to include you in important discussions and decisions, and being responsive to everyone reinforces the flat, meritocratic culture you are trying to establish. These responses can be quite short—“got it” is a favorite of ours. And when you are confident in your ability to respond quickly, you can tell people exactly what a non-response means. In our case it’s usually “got it and proceed.” Which is better than what a non-response means from most people: “I’m overwhelmed and don’t know when or if I’ll get to your note, so if you needed my feedback you’ll just have to wait in limbo a while longer. Plus I don’t like you.”

2. When writing an email, every word matters, and useless prose doesn’t. Be crisp in your delivery. If you are describing a problem, define it clearly. Doing this well requires more time, not less. You have to write a draft then go through it and eliminate any words that aren’t necessary. Think about the late novelist Elmore Leonard’s response to a question about his success as a writer: “I leave out the parts that people skip.”147 Most emails are full of stuff that people can skip.

3. Clean out your inbox constantly. How much time do you spend looking at your inbox, just trying to decide which email to answer next? How much time do you spend opening and reading emails that you have already read? Any time you spend thinking about which items in your inbox you should attack next is a waste of time. Same with any time you spend rereading a message that you have already read (and failed to act upon).

When you open a new message, you have a few options: Read enough of it to realize that you don’t need to read it, read it and act right away, read it and act later, or read it later (worth reading but not urgent and too long to read at the moment). Choose among these options right away, with a strong bias toward the first two. Remember the old OHIO acronym: Only Hold It Once. If you read the note and know what needs doing, do it right away. Otherwise you are dooming yourself to rereading it, which is 100 percent wasted time.

If you do this well, then your inbox becomes a to-do list of only the complex issues, things that require deeper thought (label these emails “take action,” or in Gmail mark them as starred), with a few “to read” items that you can take care of later.

To make sure that the bloat doesn’t simply transfer from your inbox to your “take action” folder, you must clean out the action items every day. This is a good evening activity. Zero items is the goal, but anything less than five is reasonable. Otherwise you will waste time later trying to figure out which of the long list of things to look at.

4. Handle email in LIFO order (Last In First Out). Sometimes the older stuff gets taken care of by someone else.

5. Remember, you’re a router. When you get a note with useful information, consider who else would find it useful. At the end of the day, make a mental pass through the mail you received and ask yourself, “What should I have forwarded but didn’t?”

6. When you use the bcc (blind copy) feature, ask yourself why. The answer is almost always that you are trying to hide something, which is counterproductive and potentially knavish in a transparent culture. When that is your answer, copy the person openly or don’t copy them at all.

The only time we recommend using the bcc feature is when you are removing someone from an email thread. When you “reply all” to a lengthy series of emails, move the people who are no longer relevant to the thread to the bcc field, and state in the text of the note that you are doing this. They will be relieved to have one less irrelevant note cluttering up their inbox.

7. Don’t yell. If you need to yell, do it in person. It is FAR TOO EASY to do it electronically.

8. Make it easy to follow up on requests. When you send a note to someone with an action item that you want to track, copy yourself, then label the note “follow up.” That makes it easy to find and follow up on the things that haven’t been done; just resend the original note with a new intro asking “Is this done?”

9. Help your future self search for stuff. If you get something you think you may want to recall later, forward it to yourself along with a few keywords that describe its content. Think to yourself, How will I search for this later? Then, when you search for it later, you’ll probably use those same search terms.

This isn’t just handy for emails, but important documents too. Jonathan scans his family’s passports, licenses, and health insurance cards and emails them to himself along with descriptive keywords. Should any of those things go missing during a trip, the copies are easy to retrieve from any browser.

Have a playbook

As a business leader, you have several constituencies: employees, bosses, boards of directors and advisors, customers, partners, investors, and so on. It helps to have a playbook with notes on how to communicate most effectively in each of these scenarios. Here are ours:

1:1s—match the lists

Bill Campbell once suggested to us an interesting approach to organizing 1:1s (aka one-on-ones, the periodic meetings between manager and employee). The manager should write down the top five things she wants to cover in the meeting, and the employee should do the same. When the separate lists are revealed, chances are that at least some of the items overlap. The mutual objective of any 1:1 meeting should be to solve problems, and if a manager and employee can’t independently identify the same top problems that they should solve together, there are even bigger problems afoot.

Bill also suggests a nice format for 1:1s, which we have adopted with good results:

1. Performance on job requirements

a. Could be sales figures

b. Could be product delivery or product milestones

c. Could be customer feedback or product quality

d. Could be budget numbers

2. Relationship with peer groups (critical for company integration and cohesiveness)

a. Product and Engineering

b. Marketing and Product

c. Sales and Engineering

3. Management/Leadership

a. Are you guiding/coaching your people?

b. Are you weeding out the bad ones?

c. Are you working hard at hiring?

d. Are you able to get your people to do heroic things?

4. Innovation (Best Practices)

a. Are you constantly moving ahead… thinking about how to continually get better?

b. Are you constantly evaluating new technologies, new products, new practices?

c. Do you measure yourself vs. the best in the industry/world?

Board Meetings—noses in, fingers out

The goals of a board meeting are harmony, transparency, and advice. You want to exit the meeting with the board’s support of your strategy and tactics. You need to be completely transparent in everything you communicate. And you want to hear their advice, even if you plan to ignore it—they are usually trying to be helpful, and cannot have all the context that you have. Another way to put this: You want their noses in, but fingers out.148

As CEO, Eric started his board meetings with a concise review of the highlights and lowlights of the previous quarter. The lowlights were especially important, and Eric always spent more preparation time on them than anything else. This is because it is always harder for people to present bad news to a board than good. The highlights are easy, but when you ask a team for a list of lowlights, you often get a sugarcoated version of the truth: “Here’s the problem but it’s not all that bad and we already have a solution in the works.” This can’t possibly be true for all the problems the company faces, and the board knows it. So the best approach is also the honest one: We have difficult problems and we don’t have all the answers. Eric’s lowlights brought up issues ranging from revenue to competition to products, honestly and frankly, which always set the stage for an engaged board discussion. For example, at one board meeting we wanted to discuss our concern that bureaucracy was slowing us down. The lowlight read: “Google constipated: key challenges we need to address.”

Eric followed the highlights and lowlights with a detailed review of each of the company’s product and functional areas, with an emphasis on succinct, data-driven discussions. The process of constructing this presentation wasn’t run by a communications or legal team, but by product managers on Jonathan’s team who were embedded in the business. Jonathan picked his brightest smart creatives for the task. He knew they would do a great job, despite the big time commitment the task required. He also knew that the experience of constructing detailed board presentations (and the accompanying letter) would give these talented people incredible insights into the art and skill of executive communications and a solid purview over what was going on across the company. To delegate this task to communications people would have been a huge lost opportunity to give the company’s future leaders hands-on training.149

Board members want to talk about strategy and products, not governance and lawsuits. (If this isn’t true, get new board members.) Remember this when you establish the rules and agenda of the board, and stick to it even when the going gets tough. When Eric was on the board of Siebel Systems, a software company acquired by Oracle in 2005, the company became embroiled in a series of SEC violations in the early 2000s. The board meetings became dominated by legal conversations and the board spent much more time thinking about lawyers and liabilities than it did about the business, which was slowly eroding.

Administrivia, even important board stuff, can become a nice refuge when the alternative is to have difficult conversations about the decay of the core business. The board should be of strategic value, but you won’t get these interesting conversations and valuable insights if you are constantly distracted by governance issues. Of course the board needs to understand what’s going on with critical legal stuff and other tactical issues, but these can generally be handled in subcommittees and summarized at the board level in fifteen-minute segments. When he came to Google, Eric made a commitment to the board that it would get to focus on issues relevant to the scale and strategy of the business. The Apple board also did this well during the time Eric served on it, as the meetings were full of great conversations about products, leadership, and strategy. And there was no question who was in charge!

In between meetings, call board members periodically. But hope you get voice mail. ;-)

Partners—act like diplomats

To build platforms and successful product ecosystems, companies must work with partners. This often creates interesting situations (and bastardized words: “coopetition,” “frenemy”) where the two companies may be competing in some realms but collaborating in others. The key to success in these situations lies in one of the oldest of the communications arts: diplomacy.

In many ways, complex business partnerships are similar to the realpolitik style of diplomacy between countries, which holds that relations should be managed based on pragmatic, not ideological principles. Countries can have a long list of grievances with each other, but it is in their mutual best interests to figure out a way to work together. The alternative—a lack of a relationship, or war—is destructive for everyone. For example, China and the United States have lots of issues, but there is so much trade between the two countries that we must find ways to maintain and build our relationship in spite of our differences.

Countries, like business partners, have their own belief systems, and everyone is aware when they have moved from one system to the other. An important first step in managing a successful partnership is to acknowledge those differences and assume that they are here to stay. The other country/company has a right to its own system and believes in it just as fervently as you do, so to work effectively with it as a partner, you need to put aside moral judgment. As Henry Kissinger said in 1969, when he was the US National Security Adviser, “We have always made it clear that we have no permanent enemies and that we will judge other countries, including Communist countries, and specifically countries like Communist China, on the basis of their actions and not on the basis of their domestic ideology.”150 Less than two years later he traveled to China, in secrecy, which led to the reopening of diplomatic relations between the two countries for the first time since World War II.

If managing partnerships is like diplomacy, then it stands to reason that it needs to be conducted by diplomats. For the most important partnerships, companies should create a role with the objective of serving dual constituencies: To keep the external partner happy, while also pursuing the interests of their own company.151 This is different from a traditional sales role, which is often weighted toward the company’s interests, not the partner’s.

Press Interviews—have a conversation, not a message

When you are doing a press interview, do you have people to help prepare you? If so, do they give you a document of “frequently asked questions” (FAQs) that includes all the questions that the pesky journalist might ask and a carefully scripted set of sanitized responses that are designed to stick as closely as possible to the messaging themes of the launch? When said helpful person gives you said FAQs, do you ever look at them and say to yourself, “That’s exactly what I would say?” Because if you do, you are probably made out of a silicon-titanium alloy.

Many believe that a press interview is a marketing speech, to be scripted word for word. Jonathan, who can be a rather difficult client for a communications person, used to suggest rather loudly upon seeing his scripted messages that if they wanted a trained monkey to give the interview, he’d be happy to arrange it. But if they wanted him, a person who usually bears no resemblance to a monkey, to do the interview, they better start over and come back with something intelligent to say. Because a successful interview shouldn’t be an exercise in regurgitating bland marketing messages, it should be a conversation with insight.

A good communications person will understand the difference between messaging and conversation. Messages don’t answer the question. In a conversation you listen to the questions and try to figure out a way to answer intelligently, with insights and stories, while reinforcing the message but not parroting it. Too many people try to manage the downside of communications, which messaging certainly accomplishes, but it also uniformly fails to accomplish anything else. The world can spot messaging a mile away.

Having an insightful conversation with a journalist is challenging—much more challenging than memorizing a script—and not because [insert witty barb about journalists here]. A back-and-forth conversation with a journalist often results in tension, which is something that journalists often try to create but most people try to avoid. So, if you want to engage in actual conversations with a reporter, you have to have a tough skin when the resulting article has negative elements. If you aren’t being criticized, then you probably didn’t have a good conversation.

Mostly, though, people don’t have smart conversations with the press because it is much easier to draft messages than it is to discover insights. But the insights are there, you just have to push the team to find them. Remind them, as our communications colleague Ellen West always tells her team, “To be a thought leader, you have to have a thought.”

Relationships, not hierarchy

One advantage of hierarchical, process-laden organizations is that it’s easy to figure out with whom you need to talk: Just look for the right box on the right chart, and you’ve got your person. But the steady state of a successful Internet Century venture is chaos. When things are running perfectly smoothly, with people and boxes on charts enjoying a one-to-one relationship, then the processes and infrastructure have caught up to the business. This is a bad thing. When Eric was CEO at Novell, the company was running like a well-oiled machine. The only problem was that the new-great-product cupboard was bare. (Champion racecar driver Mario Andretti: “If everything seems under control, you’re just not going fast enough.”)152

The business should always be outrunning the processes, so chaos is right where you want to be. And when you’re there, the only way to get things done is through relationships. Take the time to know and care about people. Note the little things—partner’s and kids’ names, important family issues (these can be easily recorded in your contacts). Eric believes in the three-week rule: When you start a new position, for the first three weeks don’t do anything. Listen to people, understand their issues and priorities, get to know and care about them, and earn their trust. So in fact, you are doing something: You are establishing a healthy relationship.

And don’t forget to make people smile. Praise is underused and underappreciated as a management tool. When it is deserved, don’t hold back.