Java 8 Lambdas (2014)

Chapter 4. Libraries

I’ve talked about how to write lambda expressions but so far haven’t covered the other side of the fence: how to use them. This lesson is important even if you’re not writing a heavily functional library like streams. Even the simplest application is still likely to have application code that could benefit from code as data.

Another Java 8 change that has altered the way that we need to think about libraries is the introduction of default methods and static methods on interfaces. This change means that methods on interfaces can now have bodies and contain code.

I’ll also fill in some gaps in this chapter, covering topics such as what happens when you overload methods with lambda expressions and how to use primitives. These are important things to be aware of when you’re writing lambda-enabled code.

Using Lambda Expressions in Code

In Chapter 2, I described how a lambda expression is given the type of a functional interface and how this type is inferred. From the point of view of code calling the lambda expression, you can treat it identically to calling a method on an interface.

Let’s look at a concrete example framed in terms of logging frameworks. Several commonly used Java logging frameworks, including slf4j and log4j, have methods that log output only when their logging level is set to a certain level or higher. So, they will have a method like void debug(String message) that will log message if the level is at debug.

Unfortunately, calculating the message to log frequently has a performance cost associated with it. Consequently, you end up with a situation in which people start explicitly calling the Boolean isDebugEnabled method in order to optimize this performance cost. A code sample is shown inExample 4-1. Even though a direct call to debug would have avoided logging the text, it still would had to call the expensiveOperation method and also concatenate its output to the message String, so the explicit if check still ends up being faster.

Example 4-1. A logger using isDebugEnabled to avoid performance overhead

Logger logger = new Logger();

if (logger.isDebugEnabled()) {

logger.debug("Look at this: " + expensiveOperation());

}

What we actually want to be able to do is pass in a lambda expression that generates a String to be used as the message. This expression would be called only if the Logger was actually at debug level or above. This approach would allow us to rewrite the previous code example to look like the code in Example 4-2.

Example 4-2. Using lambda expressions to simplify logging code

Logger logger = new Logger();

logger.debug(() -> "Look at this: " + expensiveOperation());

So how do we implement this method from within our Logger class? From the library point of view, we can just use the builtin Supplier functional interface, which has a single get method. We can then call isDebugEnabled in order to find out whether to call this method and pass the result into our debug method if it is enabled. The resulting code is shown in Example 4-3.

Example 4-3. The implementation of a lambda-enabled logger

public void debug(Supplier<String> message) {

if (isDebugEnabled()) {

debug(message.get());

}

}

Calling the get() method in this example corresponds to calling the lambda expression that was passed into the method to be called. This approach also conveniently works with anonymous inner classes, which allows you maintain a backward-compatible API if you have consumers of your code who can’t upgrade to Java 8 yet.

It’s important to remember that each of the different functional interfaces can have a different name for its actual method. So, if we were using a Predicate, we would have to call test, or if we were using Function, we would have to call apply.

Primitives

You might have noticed in the previous section that we skimmed over the use of primitive types. In Java we have a set of parallel types—for example, int and Integer—where one is a primitive type and the other a boxed type. Primitive types are built into the language and runtime environment as fundamental building blocks; boxed types are just normal Java classes that wrap up the primitives.

Because Java generics are based around erasing a generic parameter—in other words, pretending it’s an instance of Object—only the boxed types can be used as generic arguments. This is why if you want a list of integer values in Java it will always be List<Integer> and notList<int>.

Unfortunately, because boxed types are objects, there is a memory overhead to them. For example, although an int takes 4 bytes of memory, an Integer takes 16 bytes. This gets even worse when you start to look at arrays of numbers, as each element of a primitive array is just the size of the primitive, while each element of a boxed array is actually an in-memory pointer to another object on the Java heap. In the worst case, this might make an Integer[] take up nearly six times more memory than an int[] of the same size.

There is also a computational overhead when converting from a primitive type to a boxed type, called boxing, and vice versa, called unboxing. For algorithms that perform lots of numerical operations, the cost of boxing and unboxing combined with the additional memory bandwidth used by allocated boxed objects can make the code significantly slower.

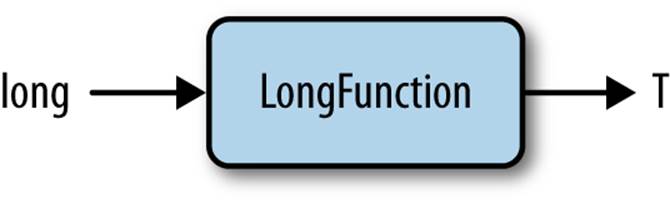

As a consequence of these performance overheads, the streams library differentiates between the primitive and boxed versions of some library functions. The mapToLong higher-order function and ToLongFunction, shown in Figure 4-1, are examples of this effort. Only the int, long, anddouble types have been chosen as the focus of the primitive specialization implementation in Java 8 because the impact is most noticeable in numerical algorithms.

Figure 4-1. ToLongFunction

The primitive specializations have a very clear-cut naming convention. If the return type is a primitive, the interface is prefixed with To and the primitive type, as in ToLongFunction (shown in Figure 4-1). If the argument type is a primitive type, the name prefix is just the type name, as inLongFunction (Figure 4-2). If the higher-order function uses a primitive type, it is suffixed with To and the primitive type, as in mapToLong.

Figure 4-2. LongFunction

There are also specialized versions of Stream for these primitive types that prefix the type name, such as LongStream. In fact, methods like mapToLong don’t return a Stream; they return these specialized streams. On the specialized streams, the map implementation is also specialized: it takes a function called LongUnaryOperator, visible in Figure 4-3, which maps a long to a long. It’s also possible to get back from a primitive stream to a boxed stream through higher-order function variations such as mapToObj and the boxed method, which returns a stream of boxed objects such as Stream<Long>.

Figure 4-3. LongUnaryOperator

It’s a good idea to use the primitive specialized functions wherever possible because of the performance benefits. You also get additional functionality available on the specialized streams. This allows you to avoid having to implement common functionality and to use code that better conveys the intent of numerical operations. You can see an example of how to use this functionality in Example 4-4.

Example 4-4. Using summaryStatistics to understand track length data

public static void printTrackLengthStatistics(Album album) {

IntSummaryStatistics trackLengthStats

= album.getTracks()

.mapToInt(track -> track.getLength())

.summaryStatistics();

System.out.printf("Max: %d, Min: %d, Ave: %f, Sum: %d",

trackLengthStats.getMax(),

trackLengthStats.getMin(),

trackLengthStats.getAverage(),

trackLengthStats.getSum());

}

Example 4-4 prints out a summary of track length information to the console. Instead of calculating that information ourselves, we map each track to its length, using the primitive specialized mapToInt method. Because this method returns an IntStream, we can callsummaryStatistics, which calculates statistics such as the minimum, maximum, average, and sum values on the IntStream.

These values are available on all the specialized streams, such as DoubleStream and LongStream. It’s also possible to calculate the individual summary statistics if you don’t need all of them through the min, max, average, and sum methods, which are all also available on all three primitive specialized Stream variants.

Overload Resolution

It’s possible in Java to overload methods, so you have multiple methods with the same name but different signatures. This approach poses a problem for parameter-type inference because it means that there are several types that could be inferred. In these situations javac will pick the most specific type for you. For example, the method call in Example 4-5, when choosing between the two methods in Example 4-6, prints out String, not Object.

Example 4-5. A method that could be dispatched to one of two methods

overloadedMethod("abc");

Example 4-6. Two methods that are overloaded

private void overloadedMethod(Object o) {

System.out.print("Object");

}

private void overloadedMethod(String s) {

System.out.print("String");

}

A BinaryOperator is special type of BiFunction for which the arguments and the return type are all the same. For example, adding two integers would be a BinaryOperator.

Because lambda expressions have the types of their functional interfaces, the same rules apply when passing them as arguments. We can overload a method with the BinaryOperator and an interface that extends it. When calling these methods, Java will infer the type of your lambda to be the most specific functional interface. For example, the code in Example 4-7 prints out IntegerBinaryOperator when choosing between the two methods in Example 4-8.

Example 4-7. Another overloaded method call

overloadedMethod((x, y) -> x + y);

Example 4-8. A choice between two overloaded methods

private interface IntegerBiFunction extends BinaryOperator<Integer> {

}

private void overloadedMethod(BinaryOperator<Integer> lambda) {

System.out.print("BinaryOperator");

}

private void overloadedMethod(IntegerBiFunction lambda) {

System.out.print("IntegerBinaryOperator");

}

Of course, when there are multiple method overloads, there isn’t always a clear “most specific type.” Take a look at Example 4-9.

Example 4-9. A compile failure due to overloaded methods

overloadedMethod((x) -> true);

private interface IntPredicate {

public boolean test(int value);

}

private void overloadedMethod(Predicate<Integer> predicate) {

System.out.print("Predicate");

}

private void overloadedMethod(IntPredicate predicate) {

System.out.print("IntPredicate");

}

The lambda expression passed into overloadedMethod is compatible with both a normal Predicate and the IntPredicate. There are method overloads for each of these options defined within this code block. In this case, javac will fail to compile the example, complaining that the lambda expression is an ambiguous method call: IntPredicate doesn’t extend any Predicate, so the compiler isn’t able to infer that it’s more specific.

The way to fix these situations is to cast the lambda expression to either IntPredicate or Predicate<Integer>, depending upon which behavior you want to call. Of course, if you’ve designed the library yourself, you might conclude that this is a code smell and you should start renaming your overloaded methods.

In summary, the parameter types of a lambda are inferred from the target type, and the inference follows these rules:

§ If there is a single possible target type, the lambda expression infers the type from the corresponding argument on the functional interface.

§ If there are several possible target types, the most specific type is inferred.

§ If there are several possible target types and there is no most specific type, you must manually provide a type.

@FunctionalInterface

Although I talked about the criteria for what a functional interface actually is back in Chapter 2, I haven’t yet mentioned the @FunctionalInterface annotation. This is an annotation that should be applied to any interface that is intended to be used as a functional interface.

What does that really mean? Well, there are some interfaces in Java that have only a single method but aren’t normally meant to be implemented by lambda expressions. For example, they might assume that the object has internal state and be interfaces with a single method only coincidentally. A couple of good examples are java.lang.Comparable and java.io.Closeable.

If a class is Comparable, it means there is a defined order between instances, such as alphabetical order for strings. You don’t normally think about functions themselves as being comparable objects because they lack fields and state, and if there are no fields and no state, what is there to sensibly compare?

For an object to be Closeable it must hold an open resource, such as a file handle that needs to be closed at some point in time. Again, the interface being called cannot be a pure function because closing a resource is really another example of mutating state.

In contrast to Closeable and Comparable, all the new interfaces introduced in order to provide Stream interoperability are expected to be implemented by lambda expressions. They are really there to bundle up blocks of code as data. Consequently, they have the@FunctionalInterface annotation applied.

Using the annotation compels javac to actually check whether the interface meets the criteria for being a functional interface. If the annotation is applied to an enum, class, or annotation, or if the type is an interface with more than one single abstract method, then javac will generate an error message. This is quite helpful for being able to catch errors easily when refactoring your code.

Binary Interface Compatibility

As you saw in Chapter 3, one of the biggest API changes in Java 8 is to the collections library. As Java has evolved, it has maintained backward binary compatibility. In practical terms, this means that if you compiled a library or application with Java 1 through 7, it’ll run out of the box in Java 8.

Of course, there are still bugs from time to time, but compared to many other programming platforms, binary compatibility has been viewed as a key Java strength. Barring the introduction of a new keyword, such as enum, there has also been an effort to maintain backward source compatibility. Here the guarantee is that if you’ve got source code in Java 1-7, it’ll compile in Java 8.

These guarantees are really hard to maintain when you’re changing such a core library component as the collections library. As a thought exercise, consider a concrete example. The stream method was added to the Collection interface in Java 8, which means that any class that implements Collection must also have this method on it. For core library classes, this problem can easily be solved by implementing that method (e.g., adding a stream method to ArrayList).

Unfortunately, this change still breaks binary compatibility because it means that any class outside of the JDK that implements Collection—say, MyCustomList—must also have implemented the stream method. In Java 8 MyCustomList would no longer compile, and even if you had a compiled version when you tried to load MyCustomList into a JVM, it would result in an exception being thrown by your ClassLoader.

This nightmare scenario of all third-party collections libraries being broken has been averted, but it did require the introduction of a new language concept: default methods.

Default Methods

So you’ve got your new stream method on Collection; how do you allow MyCustomList to compile without ever having to know about its existence? The Java 8 approach to solving the problem is to allow Collection to say, “If any of my children don’t have a stream method, they can use this one.” These methods on an interface are called default methods. They can be used on any interface, functional or not.

Another default method that has been added is the forEach method on Iterable, which provides similar functionality to the for loop but lets you use a lambda expression as the body of the loop. Example 4-10 shows how this could be implemented in the JDK.

Example 4-10. An example default method, showing how forEach might be implemented

default void forEach(Consumer<? super T> action) {

for (T t : this) {

action.accept(t);

}

}

Now that you’re familiar with the idea that you can use lambda expressions by just calling methods on interfaces, this example should look pretty simple. It uses a regular for loop to iterate over the underlying Iterable, calling the accept method with each value.

If it’s so simple, why mention it? The important thing is that new default keyword right at the beginning of the code snippet. That tells javac that you really want to add a method to an interface. Other than the addition of a new keyword, default methods also have slightly different inheritance rules to regular methods.

The other big difference is that, unlike classes, interfaces don’t have instance fields, so default methods can modify their child classes only by calling methods on them. This helps you avoid making assumptions about the implementation of their children.

Default Methods and Subclassing

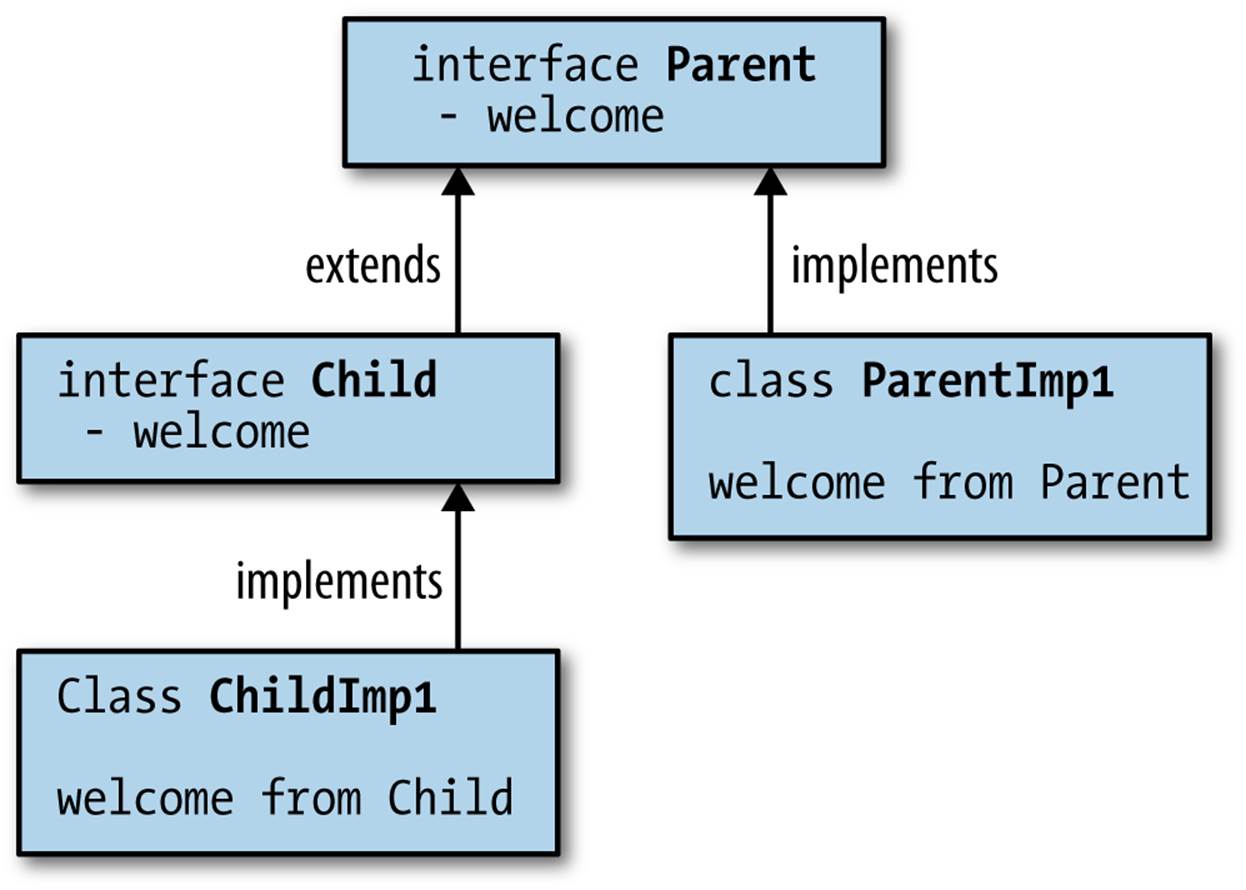

There are some subtleties about the way that default methods override and can be overridden by other methods. Let’s look the simplest case to begin with: no overriding. In Example 4-11, our Parent interface defines a welcome method that sends a message when called. TheParentImpl class doesn’t provide an implementation of welcome, so it inherits the default method.

Example 4-11. The Parent interface; the welcome method is a default

public interface Parent {

public void message(String body);

public default void welcome() {

message("Parent: Hi!");

}

public String getLastMessage();

}

When we come to call this code, in Example 4-12, the default method is called and our assertion passes.

Example 4-12. Using the default method from client code

@Test

public void parentDefaultUsed() {

Parent parent = new ParentImpl();

parent.welcome();

assertEquals("Parent: Hi!", parent.getLastMessage());

}

Now we can extend Parent with a Child interface, whose code is listed in Example 4-13. Child implements its own default welcome method. As you would intuitively expect, the default method on Child overrides the default method on Parent. In this example, again, theChildImpl class doesn’t provide an implementation of welcome, so it inherits the default method.

Example 4-13. Child interface that extends Parent

public interface Child extends Parent {

@Override

public default void welcome() {

message("Child: Hi!");

}

}

You can see the class hierarchy at this point in Figure 4-4.

Figure 4-4. A diagram showing the inheritance hierarchy at this point

Example 4-14 calls this interface and consequently ends up sending the string "Child: Hi!".

Example 4-14. Client code that calls our Child interface

@Test

public void childOverrideDefault() {

Child child = new ChildImpl();

child.welcome();

assertEquals("Child: Hi!", child.getLastMessage());

}

Now the default method is a virtual method—that is, the opposite of a static method. What this means is that whenever it comes up against competition from a class method, the logic for determining which override to pick always chooses the class. A simple example of this is shown in Examples 4-15 and 4-16, where the welcome method of OverridingParent is chosen over that of Parent.

Example 4-15. A parent class that overrides the default implementation of welcome

public class OverridingParent extends ParentImpl {

@Override

public void welcome() {

message("Class Parent: Hi!");

}

}

Example 4-16. An example of a concrete method beating a default method

@Test

public void concreteBeatsDefault() {

Parent parent = new OverridingParent();

parent.welcome();

assertEquals("Class Parent: Hi!", parent.getLastMessage());

}

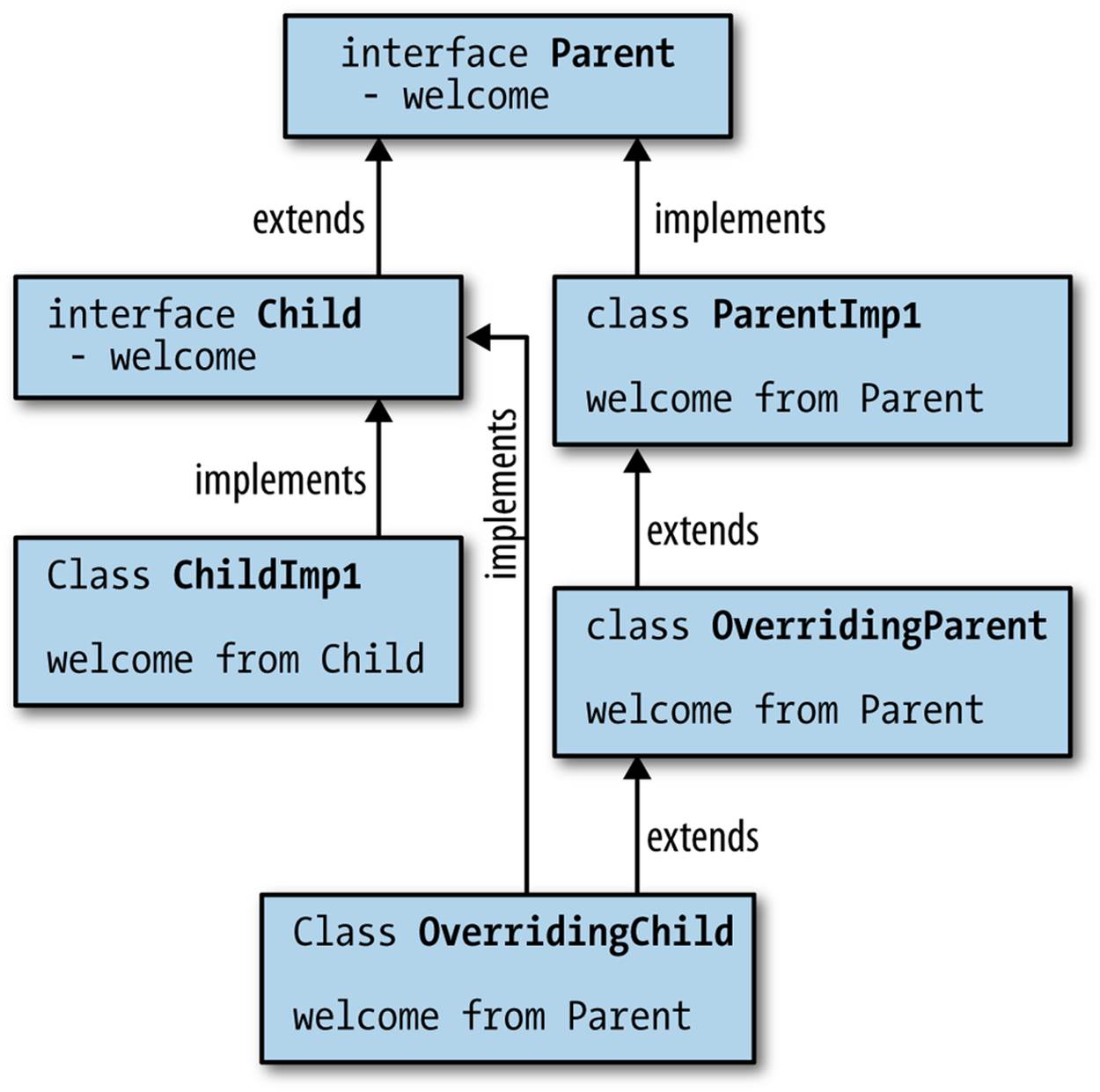

Here’s a situation, presented in Example 4-18, in which you might not expect the concrete class to override the default method. OverridingChild inherits both the welcome method from Child and the welcome method from OverridingParent and doesn’t do anything itself.OverridingParent is chosen despite OverridingChild (the code in Example 4-17), being a more specific type because it’s a concrete method from a class rather than a default method (see Figure 4-5).

Example 4-17. Again, our child interface overrides the default welcome method

public class OverridingChild extends OverridingParent implements Child {

}

Example 4-18. An example of a concrete method beating a default method that is more specific

@Test

public void concreteBeatsCloserDefault() {

Child child = new OverridingChild();

child.welcome();

assertEquals("Class Parent: Hi!", child.getLastMessage());

}

Figure 4-5. A diagram showing the complete inheritance hierarchy

Put simply: class wins. The motivation for this decision is that default methods are designed primarily to allow binary compatible API evolution. Allowing classes to win over any default methods simplifies a lot of inheritance scenarios.

Suppose we had a custom list implementation called MyCustomList and had implemented a custom addAll method, and the new List interface provided a default addAll that delegated to the add method. If the default method wasn’t guaranteed to be overridden by this addAllmethod, we could break the existing implementation.

Multiple Inheritance

Because interfaces are subject to multiple inheritance, it’s possible to get into situations where two interfaces both provide default methods with the same signature. Here’s an example in which both a Carriage and a Jukebox provide a method to rock—in each case, for different purposes. We also have a MusicalCarriage, which is both a Jukebox (Example 4-19) and a Carriage (Example 4-20) and tries to inherit the rock method.

Example 4-19. Jukebox

public interface Jukebox {

public default String rock() {

return "... all over the world!";

}

}

Example 4-20. Carriage

public interface Carriage {

public default String rock() {

return "... from side to side";

}

}

public class MusicalCarriage implements Carriage, Jukebox {

}

Because it’s not clear to javac which method it should inherit, this will just result in the compile error class MusicalCarriage inherits unrelated defaults for rock() from types Carriage and Jukebox. Of course, it’s possible to resolve this by implementing therock method, shown in Example 4-21.

Example 4-21. Implementing the rock method

public class MusicalCarriage

implements Carriage, Jukebox {

@Override

public String rock() {

return Carriage.super.rock();

}

}

This example uses the enhanced super syntax in order to pick Carriage as its preferred rock implementation. Previously, super acted as a reference to the parent class, but by using the InterfaceName.super variant it’s possible to specify a method from an inherited interface.

The Three Rules

If you’re ever unsure of what will happen with default methods or with multiple inheritance of behavior, there are three simple rules for handling conflicts:

1. Any class wins over any interface. So if there’s a method with a body, or an abstract declaration, in the superclass chain, we can ignore the interfaces completely.

2. Subtype wins over supertype. If we have a situation in which two interfaces are competing to provide a default method and one interface extends the other, the subclass wins.

3. No rule 3. If the previous two rules don’t give us the answer, the subclass must either implement the method or declare it abstract.

Rule 1 is what brings us compatibility with old code.

Tradeoffs

These changes raise a bunch of issues regarding what an interface really is in Java 8, as you can define methods with code bodies on them. This means that interfaces now provide a form of multiple inheritance that has previously been frowned upon and whose removal has been considered a usability advantage of Java over C++.

No language feature is always good or always bad. Many would argue that the real issue is multiple inheritance of state rather than just blocks of code, and as default methods avoid multiple inheritance of state, they avoid the worst pitfalls of multiple inheritance in C++.

It can also be very tempting to try and work around these limitations. Blog posts have already cropped up trying to implement full-on traits with multiple inheritance of state as well as default methods. Trying to hack around the deliberate restrictions of Java 8 puts us back into the old pitfalls of C++.

It’s also pretty clear that there’s still a distinction between interfaces and abstract classes. Interfaces give you multiple inheritance but no fields, while abstract classes let you inherit fields but you don’t get multiple inheritance. When modeling your problem domain, you need to think about this tradeoff, which wasn’t necessary in previous versions of Java.

Static Methods on Interfaces

We’ve seen a lot of calling of Stream.of but haven’t gotten into its details yet. You may recall that Stream is an interface, but this is a static method on an interface. This is another new language change that has made its way into Java 8, primarily in order to help library developers, but with benefits for day-to-day application developers as well.

An idiom that has accidentally developed over time is ending up with classes full of static methods. Sometimes a class can be an appropriate location for utility code, such as the Objects class introduced in Java 7 that contained functionality that wasn’t specific to any particular class.

Of course, when there’s a good semantic reason for a method to relate to a concept, it should always be put in the same class or interface rather than hidden in a utility class to the side. This helps structure your code in a way that’s easier for someone reading it to find the relevant method.

For example, if you want to create a simple Stream of values, you would expect the method to be located on Stream. Previously, this was impossible, and the addition of a very interface-heavy API in terms of Stream finally motivated the addition of static methods on interfaces.

NOTE

There are other methods on Stream and its primitive specialized variants. Specifically, range and iterate give us other ways of generating our own streams.

Optional

Something I’ve glossed over so far is that reduce can come in a couple of forms: the one we’ve seen, which takes an initial value, and another variant, which doesn’t. When the initial value is left out, the first call to the reducer uses the first two elements of the Stream. This is useful if there’s no sensible initial value for a reduce operation and will return an instance of Optional.

Optional is a new core library data type that is designed to provide a better alternative to null. There’s quite a lot of hatred for the old null value. Even the man who invented the concept, Tony Hoare, described it as “my billion-dollar mistake.” That’s the trouble with being an influential computer scientist—you can make a billion-dollar mistake without even seeing the billion dollars yourself!

null is often used to represent the absence of a value, and this is the use case that Optional is replacing. The problem with using null in order to represent absence is the dreaded NullPointerException. If you refer to a variable that is null, your code blows up. The goal ofOptional is twofold. First, it encourages the coder to make appropriate checks as to whether a variable is null in order to avoid bugs. Second, it documents values that are expected to be absent in a class’s API. This makes it easier to see where the bodies are buried.

Let’s take a look at the API for Optional in order to get a feel for how to use it. If you want to create an Optional instance from a value, there is a factory method called of. The Optional is now a container for this value, which can be pulled out with get, as shown in Example 4-22.

Example 4-22. Creating an Optional from a value

Optional<String> a = Optional.of("a");

assertEquals("a", a.get());

Because an Optional may also represent an absent value, there’s also a factory method called empty, and you can convert a nullable value into an Optional using the ofNullable method. Both of these are shown in Example 4-23, along with the use of the isPresent method (which indicates whether the Optional is holding a value).

Example 4-23. Creating an empty Optional and checking whether it contains a value

Optional emptyOptional = Optional.empty();

Optional alsoEmpty = Optional.ofNullable(null);

assertFalse(emptyOptional.isPresent());

// a is defined above

assertTrue(a.isPresent());

One approach to using Optional is to guard any call to get() by checking isPresent(). A neater approach is to call the orElse method, which provides an alternative value in case the Optional is empty. If creating an alternative value is computationally expensive, the orElseGetmethod should be used. This allows you to pass in a Supplier that is called only if the Optional is genuinely empty. Both of these methods are demonstrated in Example 4-24.

Example 4-24. Using orElse and orElseGet

assertEquals("b", emptyOptional.orElse("b"));

assertEquals("c", emptyOptional.orElseGet(() -> "c"));

Not only is Optional used in new Java 8 APIs, but it’s also just a regular class that you can use yourself when writing domain classes. This is definitely something to think about when trying to avoid nullness-related bugs such as uncaught exceptions.

Key Points

§ A significant performance advantage can be had by using primitive specialized lambda expressions and streams such as IntStream.

§ Default methods are methods with bodies on interfaces prefixed with the keyword default.

§ The Optional class lets you avoid using null by modeling situations where a value may not be present.

Exercises

1. Given the Performance interface in Example 4-25, add a method called getAllMusicians that returns a Stream of the artists performing and, in the case of groups, any musicians who are members of those groups. For example, if getMusicians returns The Beatles, then you should return The Beatles along with Lennon, McCartney, and so on.

Example 4-25. An interface denoting the concept of a musical performance

/** A Performance by some musicians - e.g., an Album or Gig. */

public interface Performance {

public String getName();

public Stream<Artist> getMusicians();

}

2. Based on the resolution rules described earlier, can you ever override equals or hashCode in a default method?

3. Take a look at the Artists domain class in Example 4-26, which represents a group of artists. Your assignment is to refactor the getArtist method in order to return an Optional<Artist>. It contains an element if the index is within range and is an empty Optional otherwise. Remember that you also need to refactor the getArtistName method, and it should retain the same behavior.

Example 4-26. The Artists domain class, which represents more than one Artist

public class Artists {

private List<Artist> artists;

public Artists(List<Artist> artists) {

this.artists = artists;

}

public Artist getArtist(int index) {

if (index < 0 || index >= artists.size()) {

indexException(index);

}

return artists.get(index);

}

private void indexException(int index) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException(index +

" doesn't correspond to an Artist");

}

public String getArtistName(int index) {

try {

Artist artist = getArtist(index);

return artist.getName();

} catch (IllegalArgumentException e) {

return "unknown";

}

}

}

Open Exercises

1. Look through your work code base or an open source project you’re familiar with and try to identify classes that have just static methods that could be moved to static methods on interfaces. It might be worth discussing with your colleagues whether they agree or disagree with you.