Pro Bash Programming: Scripting the GNU/Linux Shell, Second Edition (2015)

CHAPTER 11. Programming for the Command Line

This book is about programming with the shell, not about using it at the command line. You will not find information here about editing the command line, creating a command prompt (the PS1 variable), or retrieving commands from your interactive history. This chapter is about scripts that will mostly be useful at the command line rather than in other scripts.

Many of the scripts presented in this chapter are shell functions. Some of them have to be that way because they change the environment. Others are functions because they are used often and are quicker that way. Others are both functions and standalone scripts.

Manipulating the Directory Stack

The cd command remembers the previous working directory, and cd - will return to it. There is another command that will change the directory and remember an unlimited number of directories: pushd. The directories are stored in an array, DIRSTACK. To return to a previous directory,popd pulls the top entry off DIRSTACK and makes that the current directory. I use two functions that make handling DIRSTACK easier, and I’ve added a third one here just for the sake of completeness.

![]() Note The names of some of the functions that are created in this chapter are similar to the commands available in Bash. The reason for this is to use your existing shell scripts without making any changes to them and still availing of some additional functionality.

Note The names of some of the functions that are created in this chapter are similar to the commands available in Bash. The reason for this is to use your existing shell scripts without making any changes to them and still availing of some additional functionality.

cd

The cd function replaces the built-in command of the same name. The function uses the built-in command pushd to change the directory and store the new directory on DIRSTACK. If no directory is given, pushd uses $HOME. If changing the directory fails, cd prints an error message, and the function returns with a failing exit code (Listing 11-1).

Listing 11-1. cd, Change Directory, Saving Location on the Directory Stack

cd() #@ Change directory, storing new directory on DIRSTACK

{

local dir error ## variables for directory and return code

while : ## ignore all options

do

case $1 in

--) break ;;

-*) shift ;;

*) break ;;

esac

done

dir=$1

if [ -n "$dir" ] ## if a $dir is not empty

then

pushd "$dir" ## change directory

else

pushd "$HOME" ## go HOME if nothing on the command line

fi 2>/dev/null ## error message should come from cd, not pushd

error=$? ## store pushd's exit code

if [ $error -ne 0 ] ## failed, print error message

then

builtin cd "$dir" ## let the builtin cd provide the error message

fi

return "$error" ## leave with pushd's exit code

} > /dev/null

The standard output is redirected to the bit bucket because pushd prints the contents of DIRSTACK, and the only other output is sent to standard error (>&2).

![]() Note A replacement for a standard command such as cd should accept anything that the original accepts. In the case of cd, the options -L and -P are accepted, even though they are ignored. That said, I do sometimes ignore options without even making provisions for them, especially if they are ones I never use.

Note A replacement for a standard command such as cd should accept anything that the original accepts. In the case of cd, the options -L and -P are accepted, even though they are ignored. That said, I do sometimes ignore options without even making provisions for them, especially if they are ones I never use.

pd

The pd function is here for the sake of completeness (Listing 11-2). It is a lazy man’s way of calling popd; I don’t use it.

Listing 11-2. pd, Return to Previous Directory with popd

pd ()

{

popd

} >/dev/null ### for the same reason as cd

cdm

The reason I don’t use pd isn’t because I’m not lazy. Far from it, but I prefer to leave DIRSTACK intact so I can move back and forth between directories. For that reason, I use a menu that presents all the directories in DIRSTACK.

The cdm function sets the input field separator (IFS) to a single newline (NL or LF) to ensure that the output of the dirs built-in command keeps file names together after word splitting (Listing 11-3). File names containing a newline would still cause problems; names with spaces are an annoyance, but names with newlines are an abomination.

The function loops through the names in DIRSTACK (for dir in $(dirs -l -p)), adding each one to an array, item, unless it is already there. This array is then used as the argument to the menu function (discussed below), which must be sourced before cdm can be used.

DIRS BUILT-IN COMMAND

The dirs built-in command lists the directories in the DIRSTACK array. By default, it lists them on a single line with the value of HOME represented by a tilde. The -l option expands ~ to $HOME, and -p prints the directories, one per line.

Listing 11-3. cdm, Select New Directory from a Menu of Those Already Visited

cdm() #@ select new directory from a menu of those already visited

{

local dir IFS=$'\n' item

for dir in $(dirs -l -p) ## loop through diretories in DIRSTACK[@]

do

[ "$dir" = "$PWD" ] && continue ## skip current directory

case ${item[*]} in

*"$dir:"*) ;; ## $dir already in array; do nothing

*) item+=( "$dir:cd '$dir'" ) ;; ## add $dir to array

esac

done

menu "${item[@]}" Quit: ## pass array to menu function

}

When run, the menu looks like this:

$ cdm

1. /public/music/magnatune.com

2. /public/video

3. /home/jayant

4. /home/jayant/tmp/qwe rty uio p

5. /home/jayant/tmp

6. Quit

(1 to 6) ==>

menu

The calling syntax for the menu function comes from 9menu, which was part of the Plan 9 operating system. Each argument contains two colon-separated fields: the item to be displayed and the command to be executed. If there is no colon in an argument, it is used both as the display and as the command:

$ menu who date "df:df ."

1. who

2. date

3. df

(1 to 3) ==> 3

Filesystem 1K-blocks Used Available Use% Mounted on

/dev/hda5 48070472 43616892 2011704 96% /home

$ menu who date "df: df ."

1. who

2. date

3. df

(1 to 3) ==> 1

jayant tty8 Jun 18 14:00 (:1)

jayant tty2 Jun 21 18:10

A for loop numbers and prints the menu; read gets the response; and a case statement checks for the exit characters q, Q, or 0 in the response. Finally, indirect expansion retrieves the selected item, further expansion extracts the command, and eval executes it: eval "${!num#*:}" (Listing 11-4).

Listing 11-4. menu, Print Menu, and Execute-Associated Command

menu()

{

local IFS=$' \t\n' ## Use default setting of IFS

local num n=1 opt item cmd

echo

## Loop though the command-line arguments

for item

do

printf " %3d. %s\n" "$n" "${item%%:*}"

n=$(( $n + 1 ))

done

echo

## If there are fewer than 10 items, set option to accept key without ENTER

if [ $# -lt 10 ]

then

opt=-sn1

else

opt=

fi

read -p " (1 to $#) ==> " $opt num ## Get response from user

## Check that user entry is valid

case $num in

[qQ0] | "" ) return ;; ## q, Q or 0 or "" exits

*[!0-9]* | 0*) ## invalid entry

printf "\aInvalid response: %s\n" "$num" >&2

return 1

;;

esac

echo

if [ "$num" -le "$#" ] ## Check that number is <= to the number of menu items

then

eval "${!num#*:}" ## Execute it using indirect expansion

else

printf "\aInvalid response: %s\n" "$num" >&2

return 1

fi

}

Filesystem Functions

These functions vary from laziness (giving a short name to a longer command) to adding functionality to standard commands (cp and mv). They list, copy, or move files or create directories.

l

There is no single-letter command required by the POSIX specification, and there is only one that is found on most Unixes: w, which shows who is logged on and what they are doing. I have defined a number of single-letter functions:

· a: Lists the currently playing music track

· c: Clears the screen (sometimes quicker or easier than ^L)

· d: The date "+%A, %-d %B %Y %-I:%M:%S %P (%H:%M:%S)"

· k: Is equivalent to man -k, or apropos

· t: For the Amiga and MS-DOS command type, invokes less

· v and V: Lowers and raises the sound volume, respectively

· x: Logout

And there’s the one I use most that pipes a long file listing through less, as shown in Listing 11-5.

Listing 11-5. l, List Files in Long Format, Piped Through less

l()

{

ls -lA "$@" | less ## the -A option is specific to GNU and *BSD versions

}

lsr

The commands I use most frequently are l, cd, xx.sh, cdm, and lsr; xx.sh is a file for throwaway scripts. I keep adding new ones to the top; lsr displays the most recent files (or with the -o option, the oldest files). The default setting is for ten files to be shown, but that can be changed with the -n option.

The script in Listing 11-6 uses the -t (or -tr) option to ls and pipes the result to head.

Listing 11-6. lsr, List Most Recently Modified Files

num=10 ## number of files to print

short=0 ## set to 1 for short listing

timestyle='--time-style="+ %d-%b-%Y %H:%M:%S "' ## GNU-specific time format

opts=Aadn:os

while getopts $opts opt

do

case $opt in

a|A|d) ls_opts="$ls_opts -$opt" ;; ## options passed to ls

n) num=$OPTARG ;; ## number of files to display

o) ls_opts="$ls_opts -r" ;; ## show oldest files, not newest

s) short=$(( $short + 1 )) ;;

esac

done

shift $(( $OPTIND - 1 ))

case $short in

0) ls_opts="$ls_opts -l -t" ;; ## long listing, use -l

*) ls_opts="$ls_opts -t" ;; ## short listing, do not use -l

esac

ls $ls_opts $timestyle "$@" | {

read ## In bash, the same as: IFS= read -r REPLY

case $line in

total*) ;; ## do not display the 'total' line

*) printf "%s\n" "$REPLY" ;;

esac

cat

} | head -n$num

cp, mv

Before switching my desktop to GNU/Linux, I used an Amiga. Its copy command would copy a file to the current directory if no destination was given. This function gives the same ability as cp (Listing 11-7). The -b option is GNU specific, so remove it if you are using a different version of cp.

Listing 11-7. cp, Copy, Using the Current Directory if No Destination Is Given

cp()

{

local final

if [ $# -eq 1 ] ## Only one arg,

then

command cp -b "$1" . ## so copy it to the current directory

else

final=${!#}

if [ -d "$final" ] ## if last arg is a directory

then

command cp -b "$@" ## copy all the files into it

else

command cp -b "$@" . ## otherwise, copy to the current directory

fi

fi

}

The mv function is identical except that it has mv wherever cp appears in that function.

md

Laziness is the order of the day with the md function (Listing 11-8). It calls mkdir with the -p option to create intermediate directories if they don’t exist. With the -c option, md creates the directory (if it doesn’t already exist) and then cds into it. Because of the -p option, no error is generated if the directory exists.

Listing 11-8. md, Create a New Directory and Intermediate Directories and Optionally cd into It

md() { #@ create new directory, including intermediate directories if necessary

case $1 in

-c) mkdir -p "$2" && cd "$2" ;;

*) mkdir -p "$@" ;;

esac

}

Miscellaneous Functions

I use the next two functions a great deal, but they don’t fit into any category.

pr1

I have the pr1 function as both a function and a stand-alone script (Listing 11-9). It prints each of its argument on a separate line. By default, it limits the length to the number of columns in the terminal, truncating lines as necessary.

There are two options, -w and -W. The former removes the truncation, so lines will always print in full, wrapping to the next line when necessary. The latter specifies a width at which to truncate lines.

Listing 11-9. pr1, Function to Print Its Argument One to a Line

pr1() #@ Print arguments one to a line

{

case $1 in

-w) pr_w= ## width specification modifier

shift

;;

-W) pr_w=${2}

shift 2

;;

-W*) pr_w=${1#??}

shift

;;

*) pr_w=-.${COLUMNS:-80} ## default to number of columns in window

;;

esac

printf "%${pr_w}s\n" "$@"

}

The script version (Listing 11-10) uses getopts; I didn’t use them in the function because I wanted it to be POSIX compliant.

Listing 11-10. pr1, Script to Print Its Arguments One to a Line

while getopts wW: opt

do

case $opt in

w) w=

shift

;;

W) w=$OPTARG ;;

*) w=-.${COLUMNS:-80} ;;

esac

done

shift $(( $OPTIND - 1 ))

printf "%${w}s\n" "$@"

calc

Bash lacks the capacity for arithmetic with decimal fractions, so I wrote this function (Listing 11-11) to use awk to do the dirty work. Note that characters special to the shell must be escaped or quoted on the command line. This applies particularly to the multiplication symbol, *.

Listing 11-11. calc, Print Result of Arithmetic Expression

calc() #@ Perform arithmetic, including decimal fractions

{

local result=$(awk 'BEGIN { OFMT="%f"; print '"$*"'; exit}')

case $result in

*.*0) result=${result%"${result##*[!0]}"} ;;

esac

printf "%s\n" "$result"

}

The case statement removes trailing zeroes after a decimal point.

Managing Man Pages

I use three functions related to man pages. The first searches a man page for a pattern or string, the second looks up a POSIX man page, and the third is equivalent to man -k.

sman

The sman function calls up a man page and searches for a given string. It assumes that less is the default pager (Listing 11-12).

Listing 11-12. sman, Call Up a Man Page and Search for a Pattern

sman() #@ USAGE: sman command search_pattern

{

LESS="$LESS${2:+ +/$2}" man "$1"

}

sus

When I want to check the portability of a given command or, more usually, to check which options are specified by POSIX, I use sus. It stores a copy of the POSIX man page locally so that it doesn’t need to be fetched on subsequent queries (Listing 11-13).

Listing 11-13. sus, Look Up a Man Page in the POSIX Spec

sus()

{

local html_file=/usr/share/sus/$1.html ## adjust to taste

local dir=9699919799

local sus_dir=http://www.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/$dir/utilities/

[ -f "$html_file" ] ||

lynx -source $sus_dir${1##*/}.html > $html_file ##>/dev/null 2>&1

lynx -dump -nolist $html_file | ${PAGER:-less}

}

Here lynx is a text-mode web browser. Though normally used interactively to access the Web, the -source and -dump directives can be used in scripts.

k

The k function saves all the typing of apropos or man -k. It actually does a little more. It filters the result so that only user commands (from the first section of the man pages) show. System and kernel functions and file specifications, and so on, do not get shown (Listing 11-14).

Listing 11-14. k, List Commands Whose Short Descriptions Include a Search String

k() #@ USAGE: k string

{

man -k "$@" | grep '(1'

}

Games

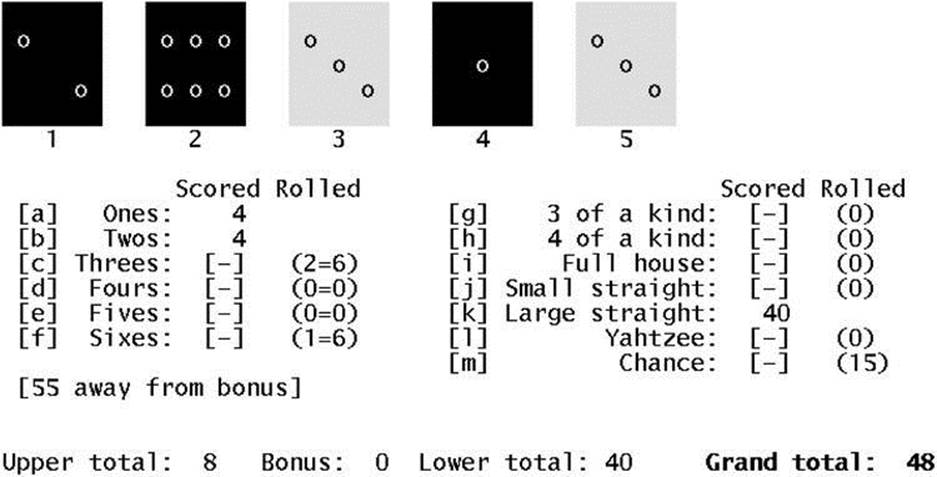

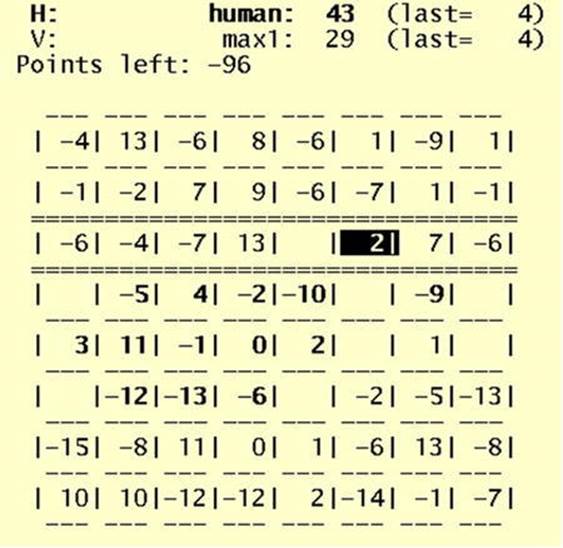

What’s a command line without games? Boring, that’s what! I have written a number of games using the shell. They include yahtzee (Figure 11-1), a game that uses five dice; maxit (Figure 11-2), based on an arithmetic game for the Commodore 64; and, of course, tic-tac-toe(Figure 11-3). All these games are too large to include their scripts in this book, but sections of them (such as the yahtzee dice) will be demonstrated in later chapters. The one game that I can include here is the fifteen puzzle.

Figure 11-1. The game of yahtzee, in which the player attempts to get runs, a full house, or three, four, or five of a kind

Figure 11-2. The game of maxit, in which one player selects from a row, and the other from a column

Figure 11-3. The ubiquitous game of tic-tac-toe

The fifteen Puzzle

The fifteen puzzle consists of 15 numbered, sliding tiles in a frame; the object is to arrange them in ascending order like this:

+----+----+----+----+

| | | | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| | | | |

+----+----+----+----+

| | | | |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| | | | |

+----+----+----+----+

| | | | |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| | | | |

+----+----+----+----+

| | | | |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | |

| | | | |

+----+----+----+----+

In this script (Listing 11-15), the tiles are moved with the cursor keys.

Listing 11-15. fifteen, Place Tiles in Ascending Order

########################################

## Meta data

########################################

scriptname=${0##*/}

description="The Fifteen Puzzle"

author="Chris F.A. Johnson"

created=2009-06-20

########################################

## Variables

########################################

board=( {1..15} "" ) ## The basic board array

target=( "${board[@]}" ) ## A copy for comparison (the target)

empty=15 ## The empty square

last=0 ## The last move made

A=0 B=1 C=2 D=3 ## Indices into array of possible moves

topleft='\e[0;0H' ## Move cursor to top left corner of window

nocursor='\e[?25l' ## Make cursor invisible

normal=\e[0m\e[?12l\e[?25h ## Resume normal operation

## Board layout is a printf format string

## At its most basic, it could be a simple:

fmt="$nocursor$topleft

%2s %2s %2s %2s

%2s %2s %2s %2s

%2s %2s %2s %2s

%2s %2s %2s %2s

"

## I prefer this ASCII board

fmt="\e[?25l\e[0;0H\n

\t+----+----+----+----+

\t| | | | |

\t| %2s | %2s | %2s | %2s |

\t| | | | |

\t+----+----+----+----+

\t| | | | |

\t| %2s | %2s | %2s | %2s |

\t| | | | |

\t+----+----+----+----+

\t| | | | |

\t| %2s | %2s | %2s | %2s |

\t| | | | |

\t+----+----+----+----+

\t| | | | |

\t| %2s | %2s | %2s | %2s |

\t| | | | |

\t+----+----+----+----+\n\n"

########################################

### Functions

########################################

print_board() #@ What the name says

{

printf "$fmt" "${board[@]}"

}

borders() #@ List squares bordering on the empty square

{

## Calculate x/y co-ordinates of the empty square

local x=$(( ${empty:=0} % 4 )) y=$(( $empty / 4 ))

## The array, bordering, has 4 elements, corresponding to the 4 directions

## If a move in any direction would be off the board, that element is empty

##

unset bordering ## clear array before setting it

[ $y -lt 3 ] && bordering[$A]=$(( $empty + 4 ))

[ $y -gt 0 ] && bordering[$B]=$(( $empty - 4 ))

[ $x -gt 0 ] && bordering[$C]=$(( $empty - 1 ))

[ $x -lt 3 ] && bordering[$D]=$(( $empty + 1 ))

}

check() #@ Check whether puzzle has been solved

{

## Compare current board with target

if [ "${board[*]}" = "${target[*]}" ]

then

## Puzzle is completed, print message and exit

print_board

printf "\a\tCompleted in %d moves\n\n" "$moves"

exit

fi

}

move() #@ Move the square in $1

{

movelist="$empty $movelist" ## add current empty square to the move list

moves=$(( $moves + 1 )) ## increment move counter

board[$empty]=${board[$1]} ## put $1 into the current empty square

board[$1]="" ## remove number from new empty square

last=$empty ## .... and put it in old empty square

empty=$1 ## set new value for empty-square pointer

}

random_move() #@ Move one of the squares in the arguments

{

## The arguments to random_move are the squares that can be moved

## (as generated by the borders function)

local sq

while :

do

sq=$(( $RANDOM % $# + 1 ))

sq=${!sq}

[ $sq -ne ${last:-666} ] && ## do not undo last move

break

done

move "$sq"

}

shuffle() #@ Mix up the board using legitimate moves (to ensure solvable puzzle)

{

local n=0 max=$(( $RANDOM % 100 + 150 )) ## number of moves to make

while [ $(( n += 1 )) -lt $max ]

do

borders ## generate list of possible moves

random_move "${bordering[@]}" ## move to one of them at random

done

}

########################################

### End of functions

########################################

trap 'printf "$normal"' EXIT ## return terminal to normal state on exit

########################################

### Instructions and initialization

########################################

clear

print_board

echo

printf "\t%s\n" "$description" "by $author, ${created%%-*}" ""

printf "

Use the cursor keys to move the tiles around.

The game is finished when you return to the

position shown above.

Try to complete the puzzle in as few moves

as possible.

Press \e[1mENTER\e[0m to continue

"

shuffle ## randomize board

moves=0 ## reset move counter

read -s ## wait for user

clear ## clear the screen

########################################

### Main loop

########################################

while :

do

borders

print_board

printf "\t %d move" "$moves"

[ $moves -ne 1 ] && printf "s"

check

## read a single character without waiting for <ENTER>

read -sn1 -p $' \e[K' key

## The cursor keys generate three characters: ESC, [ and A, B, C, or D;

## this loop will run three times for each press of a cursor key

## but will not do anything until it receives a letter

## from the cursor key (or entered directly with A etc.), or a 'q' to exit

case $key in

A) [ -n "${bordering[$A]}" ] && move "${bordering[$A]}" ;;

B) [ -n "${bordering[$B]}" ] && move "${bordering[$B]}" ;;

C) [ -n "${bordering[$C]}" ] && move "${bordering[$C]}" ;;

D) [ -n "${bordering[$D]}" ] && move "${bordering[$D]}" ;;

q) echo; break ;;

esac

done

Summary

The scripts provided in this chapter are a smattering of the possibilities for using scripts at the command line. Where the environment needs to be changed (as in cd and cdm), the scripts must be shell functions. These are usually kept in $HOME/.bashrc or in a file sourced by .bashrc.

Even games can be programmed without needing a GUI interface.

Exercises

1. Modify the menu function to accept its parameters from a file.

2. Rewrite the pr1 function as prx that will behave in the manner of pr4 from Chapter 8 but will take an option for any number of columns.

3. Add a getopts section to the fifteen game that allows the user to select between three different board formats. Write a third format.

All materials on the site are licensed Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported CC BY-SA 3.0 & GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL)

If you are the copyright holder of any material contained on our site and intend to remove it, please contact our site administrator for approval.

© 2016-2026 All site design rights belong to S.Y.A.