Game Programming Patterns (2014)

Decoupling Patterns

Once you get the hang of a programming language, writing code to do what you want is actually pretty easy. What’s hard is writing code that’s easy to adapt when your requirements change. Rarely do we have the luxury of a perfect feature set before we’ve fired up our editor.

A powerful tool we have for making change easier is decoupling. When we say two pieces of code are “decoupled”, we mean a change in one usually doesn’t require a change in the other. When you change some feature in your game, the fewer places in code you have to touch, the easier it is.

Components decouple different domains in your game from each other within a single entity that has aspects of all of them. Event Queues decouple two objects communicating with each other, both statically and in time. Service Locators let code access a facility without being bound to the code that provides it.

The Patterns

· Component

· Event Queue

· Service Locator

Component

Intent

Allow a single entity to span multiple domains without coupling the domains to each other.

Motivation

Let’s say we’re building a platformer. The Italian plumber demographic is covered, so ours will star a Danish baker, Bjørn. It stands to reason that we’ll have a class representing our friendly pastry chef, and it will contain everything he does in the game.

Brilliant game ideas like this are why I’m a programmer and not a designer.

Since the player controls him, that means reading controller input and translating that input into motion. And, of course, he needs to interact with the level, so some physics and collision go in there. Once that’s done, he’s got to show up on screen, so toss in animation and rendering. He’ll probably play some sounds too.

Hold on a minute; this is getting out of control. Software Architecture 101 tells us that different domains in a program should be kept isolated from each other. If we’re making a word processor, the code that handles printing shouldn’t be affected by the code that loads and saves documents. A game doesn’t have the same domains as a business app, but the rule still applies.

As much as possible, we don’t want AI, physics, rendering, sound and other domains to know about each other, but now we’ve got all of that crammed into one class. We’ve seen where this road leads to: a 5,000-line dumping ground source file so big that only the bravest ninja coders on your team even dare to go in there.

This is great job security for the few who can tame it, but it’s hell for the rest of us. A class that big means even the most seemingly trivial changes can have far-reaching implications. Soon, the class collects bugs faster than it collects features.

The Gordian knot

Even worse than the simple scale problem is the coupling one. All of the different systems in our game have been tied into a giant knotted ball of code like:

if (collidingWithFloor() && (getRenderState() != INVISIBLE))

{

playSound(HIT_FLOOR);

}

Any programmer trying to make a change in code like that will need to know something about physics, graphics, and sound just to make sure they don’t break anything.

While coupling like this sucks in any game, it’s even worse on modern games that use concurrency. On multi-core hardware, it’s vital that code is running on multiple threads simultaneously. One common way to split a game across threads is along domain boundaries — run AI on one core, sound on another, rendering on a third, etc.

Once you do that, it’s critical that those domains stay decoupled in order to avoid deadlocks or other fiendish concurrency bugs. Having a single class with an UpdateSounds() method that must be called from one thread and a RenderGraphics() method that must be called from another is begging for those kinds of bugs to happen.

These two problems compound each other; the class touches so many domains that every programmer will have to work on it, but it’s so huge that doing so is a nightmare. If it gets bad enough, coders will start putting hacks in other parts of the codebase just to stay out of the hairball that thisBjorn class has become.

Cutting the knot

We can solve this like Alexander the Great — with a sword. We’ll take our monolithic Bjorn class and slice it into separate parts along domain boundaries. For example, we’ll take all of the code for handling user input and move it into a separate InputComponent class. Bjorn will then own an instance of this component. We’ll repeat this process for each of the domains that Bjorn touches.

When we’re done, we’ll have moved almost everything out of Bjorn. All that remains is a thin shell that binds the components together. We’ve solved our huge class problem by simply dividing it up into multiple smaller classes, but we’ve accomplished more than just that.

Loose ends

Our component classes are now decoupled. Even though Bjorn has a PhysicsComponent and a GraphicsComponent, the two don’t know about each other. This means the person working on physics can modify their component without needing to know anything about graphics and vice versa.

In practice, the components will need to have some interaction between themselves. For example, the AI component may need to tell the physics component where Bjørn is trying to go. However, we can restrict this to the components that do need to talk instead of just tossing them all in the same playpen together.

Tying back together

Another feature of this design is that the components are now reusable packages. So far, we’ve focused on our baker, but let’s consider a couple of other kinds of objects in our game world. Decorations are things in the world the player sees but doesn’t interact with: bushes, debris and other visual detail. Props are like decorations but can be touched: boxes, boulders, and trees. Zones are the opposite of decorations — invisible but interactive. They’re useful for things like triggering a cutscene when Bjørn enters an area.

When object-oriented programming first hit the scene, inheritance was the shiniest tool in its toolbox. It was considered the ultimate code-reuse hammer, and coders swung it often. Since then, we’ve learned the hard way that it’s a heavy hammer indeed. Inheritance has its uses, but it’s often too cumbersome for simple code reuse.

Instead, the growing trend in software design is to use composition instead of inheritance when possible. Instead of sharing code between two classes by having them inherit from the same class, we do so by having them both own an instance of the same class.

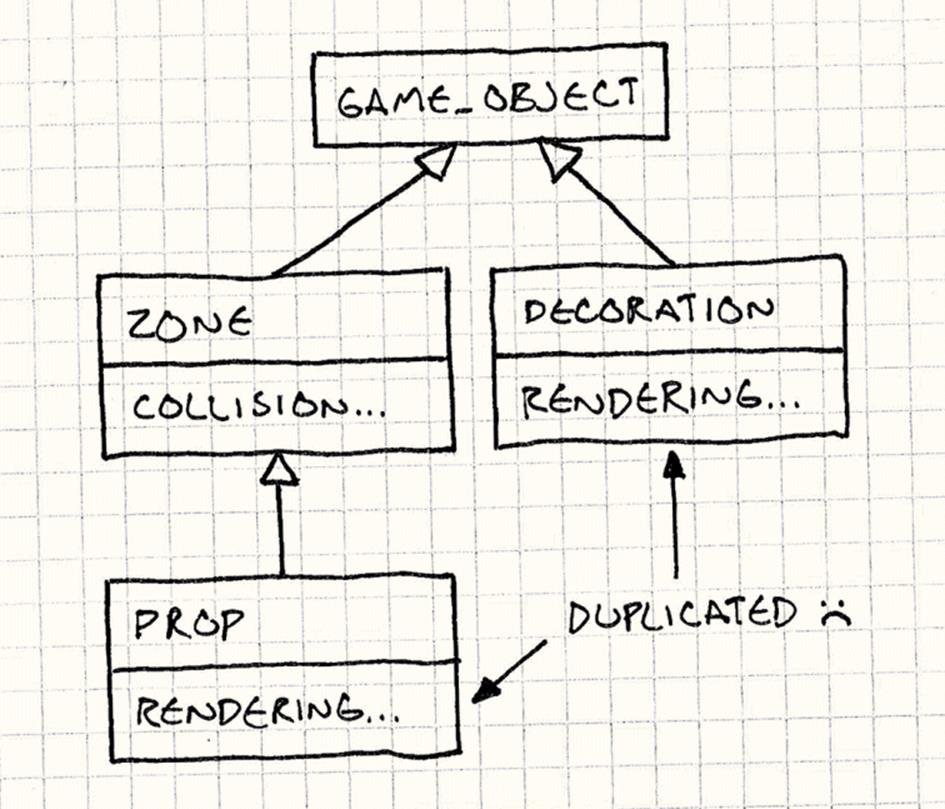

Now, consider how we’d set up an inheritance hierarchy for those classes if we weren’t using components. A first pass might look like:

We have a base GameObject class that has common stuff like position and orientation. Zone inherits from that and adds collision detection. Likewise, Decoration inherits from GameObject and adds rendering. Prop inherits from Zone, so it can reuse the collision code. However, Prop can’t alsoinherit from Decoration to reuse the rendering code without running into the Deadly Diamond.

The “Deadly Diamond” occurs in class hierarchies with multiple inheritance where there are two different paths to the same base class. The pain that causes is a bit out of the scope of this book, but understand that they named it “deadly” for a reason.

We could flip things around so that Prop inherits from Decoration, but then we end up having to duplicate the collision code. Either way, there’s no clean way to reuse the collision and rendering code between the classes that need it without resorting to multiple inheritance. The only other option is to push everything up into GameObject, but then Zone is wasting memory on rendering data it doesn’t need and Decoration is doing the same with physics.

Now, let’s try it with components. Our subclasses disappear completely. Instead, we have a single GameObject class and two component classes: PhysicsComponent and GraphicsComponent. A decoration is simply a GameObject with a GraphicsComponent but no PhysicsComponent. A zone is the opposite, and a prop has both components. No code duplication, no multiple inheritance, and only three classes instead of four.

A restaurant menu is a good analogy. If each entity is a monolithic class, it’s like you can only order combos. We need to have a separate class for each possible combination of features. To satisfy every customer, we would need dozens of combos.

Components are à la carte dining — each customer can select just the dishes they want, and the menu is a list of the dishes they can choose from.

Components are basically plug-and-play for objects. They let us build complex entities with rich behavior by plugging different reusable component objects into sockets on the entity. Think software Voltron.

The Pattern

A single entity spans multiple domains. To keep the domains isolated, the code for each is placed in its own component class. The entity is reduced to a simple container of components.

“Component”, like “Object”, is one of those words that means everything and nothing in programming. Because of that, it’s been used to describe a few concepts. In business software, there’s a “Component” design pattern that describes decoupled services that communicate over the web.

I tried to find a different name for this unrelated pattern found in games, but “Component” seems to be the most common term for it. Since design patterns are about documenting existing practices, I don’t have the luxury of coining a new term. So, following in the footsteps of XNA, Delta3D, and others, “Component” it is.

When to Use It

Components are most commonly found within the core class that defines the entities in a game, but they may be useful in other places as well. This pattern can be put to good use when any of these are true:

· You have a class that touches multiple domains which you want to keep decoupled from each other.

· A class is getting massive and hard to work with.

· You want to be able to define a variety of objects that share different capabilities, but using inheritance doesn’t let you pick the parts you want to reuse precisely enough.

Keep in Mind

The Component pattern adds a good bit of complexity over simply making a class and putting code in it. Each conceptual “object” becomes a cluster of objects that must be instantiated, initialized, and correctly wired together. Communication between the different components becomes more challenging, and controlling how they occupy memory is more complex.

For a large codebase, this complexity may be worth it for the decoupling and code reuse it enables, but take care to ensure you aren’t over-engineering a “solution” to a non-existent problem before applying this pattern.

Another consequence of using components is that you often have to hop through a level of indirection to get anything done. Given the container object, first you have to get the component you want, then you can do what you need. In performance-critical inner loops, this pointer following may lead to poor performance.

There’s a flip side to this coin. The Component pattern can often improve performance and cache coherence. Components make it easier to use the Data Locality pattern to organize your data in the order that the CPU wants it.

Sample Code

One of the biggest challenges for me in writing this book is figuring out how to isolate each pattern. Many design patterns exist to contain code that itself isn’t part of the pattern. In order to distill the pattern down to its essence, I try to cut as much of that out as possible, but at some point it becomes a bit like explaining how to organize a closet without showing any clothes.

The Component pattern is a particularly hard one. You can’t get a real feel for it without seeing some code for each of the domains that it decouples, so I’ll have to sketch in a bit more of Bjørn’s code than I’d like. The pattern is really only the component classes themselves, but the code in them should help clarify what the classes are for. It’s fake code — it calls into other classes that aren’t presented here — but it should give you an idea of what we’re going for.

A monolithic class

To get a clearer picture of how this pattern is applied, we’ll start by showing a monolithic Bjorn class that does everything we need but doesn’t use this pattern:

I should point out that using the actual name of the character in the codebase is usually a bad idea. The marketing department has an annoying habit of demanding name changes days before you ship. “Focus tests show males between 11 and 15 respond negatively to ‘Bjørn’. Use ‘Sven’ instead.”

This is why many software projects use internal-only codenames. Well, that and because it’s more fun to tell people you’re working on “Big Electric Cat” than just “the next version of Photoshop.”

class Bjorn

{

public:

Bjorn()

: velocity_(0),

x_(0), y_(0)

{}

void update(World& world, Graphics& graphics);

private:

static const int WALK_ACCELERATION = 1;

int velocity_;

int x_, y_;

Volume volume_;

Sprite spriteStand_;

Sprite spriteWalkLeft_;

Sprite spriteWalkRight_;

};

Bjorn has an update() method that gets called once per frame by the game:

void Bjorn::update(World& world, Graphics& graphics)

{

// Apply user input to hero's velocity.

switch (Controller::getJoystickDirection())

{

case DIR_LEFT:

velocity_ -= WALK_ACCELERATION;

break;

case DIR_RIGHT:

velocity_ += WALK_ACCELERATION;

break;

}

// Modify position by velocity.

x_ += velocity_;

world.resolveCollision(volume_, x_, y_, velocity_);

// Draw the appropriate sprite.

Sprite* sprite = &spriteStand_;

if (velocity_ < 0)

{

sprite = &spriteWalkLeft_;

}

else if (velocity_ > 0)

{

sprite = &spriteWalkRight_;

}

graphics.draw(*sprite, x_, y_);

}

It reads the joystick to determine how to accelerate the baker. Then it resolves its new position with the physics engine. Finally, it draws Bjørn onto the screen.

The sample implementation here is trivially simple. There’s no gravity, animation, or any of the dozens of other details that make a character fun to play. Even so, we can see that we’ve got a single function that several different coders on our team will probably have to spend time in, and it’s starting to get a bit messy. Imagine this scaled up to a thousand lines and you can get an idea of how painful it can become.

Splitting out a domain

Starting with one domain, let’s pull a piece out of Bjorn and push it into a separate component class. We’ll start with the first domain that gets processed: input. The first thing Bjorn does is read in user input and adjust his velocity based on it. Let’s move that logic out into a separate class:

class InputComponent

{

public:

void update(Bjorn& bjorn)

{

switch (Controller::getJoystickDirection())

{

case DIR_LEFT:

bjorn.velocity -= WALK_ACCELERATION;

break;

case DIR_RIGHT:

bjorn.velocity += WALK_ACCELERATION;

break;

}

}

private:

static const int WALK_ACCELERATION = 1;

};

Pretty simple. We’ve taken the first section of Bjorn’s update() method and put it into this class. The changes to Bjorn are also straightforward:

class Bjorn

{

public:

int velocity;

int x, y;

void update(World& world, Graphics& graphics)

{

input_.update(*this);

// Modify position by velocity.

x += velocity;

world.resolveCollision(volume_, x, y, velocity);

// Draw the appropriate sprite.

Sprite* sprite = &spriteStand_;

if (velocity < 0)

{

sprite = &spriteWalkLeft_;

}

else if (velocity > 0)

{

sprite = &spriteWalkRight_;

}

graphics.draw(*sprite, x, y);

}

private:

InputComponent input_;

Volume volume_;

Sprite spriteStand_;

Sprite spriteWalkLeft_;

Sprite spriteWalkRight_;

};

Bjorn now owns an InputComponent object. Where before he was handling user input directly in the update() method, now he delegates to the component:

input_.update(*this);

We’ve only started, but already we’ve gotten rid of some coupling — the main Bjorn class no longer has any reference to Controller. This will come in handy later.

Splitting out the rest

Now, let’s go ahead and do the same cut-and-paste job on the physics and graphics code. Here’s our new PhysicsComponent:

class PhysicsComponent

{

public:

void update(Bjorn& bjorn, World& world)

{

bjorn.x += bjorn.velocity;

world.resolveCollision(volume_,

bjorn.x, bjorn.y, bjorn.velocity);

}

private:

Volume volume_;

};

In addition to moving the physics behavior out of the main Bjorn class, you can see we’ve also moved out the data too: The Volume object is now owned by the component.

Last but not least, here’s where the rendering code lives now:

class GraphicsComponent

{

public:

void update(Bjorn& bjorn, Graphics& graphics)

{

Sprite* sprite = &spriteStand_;

if (bjorn.velocity < 0)

{

sprite = &spriteWalkLeft_;

}

else if (bjorn.velocity > 0)

{

sprite = &spriteWalkRight_;

}

graphics.draw(*sprite, bjorn.x, bjorn.y);

}

private:

Sprite spriteStand_;

Sprite spriteWalkLeft_;

Sprite spriteWalkRight_;

};

We’ve yanked almost everything out, so what’s left of our humble pastry chef? Not much:

class Bjorn

{

public:

int velocity;

int x, y;

void update(World& world, Graphics& graphics)

{

input_.update(*this);

physics_.update(*this, world);

graphics_.update(*this, graphics);

}

private:

InputComponent input_;

PhysicsComponent physics_;

GraphicsComponent graphics_;

};

The Bjorn class now basically does two things: it holds the set of components that actually define it, and it holds the state that is shared across multiple domains. Position and velocity are still in the core Bjorn class for two reasons. First, they are “pan-domain” state — almost every component will make use of them, so it isn’t clear which component should own them if we did want to push them down.

Secondly, and more importantly, it gives us an easy way for the components to communicate without being coupled to each other. Let’s see if we can put that to use.

Robo-Bjørn

So far, we’ve pushed our behavior out to separate component classes, but we haven’t abstracted the behavior out. Bjorn still knows the exact concrete classes where his behavior is defined. Let’s change that.

We’ll take our component for handling user input and hide it behind an interface. We’ll turn InputComponent into an abstract base class:

class InputComponent

{

public:

virtual ~InputComponent() {}

virtual void update(Bjorn& bjorn) = 0;

};

Then, we’ll take our existing user input handling code and push it down into a class that implements that interface:

class PlayerInputComponent : public InputComponent

{

public:

virtual void update(Bjorn& bjorn)

{

switch (Controller::getJoystickDirection())

{

case DIR_LEFT:

bjorn.velocity -= WALK_ACCELERATION;

break;

case DIR_RIGHT:

bjorn.velocity += WALK_ACCELERATION;

break;

}

}

private:

static const int WALK_ACCELERATION = 1;

};

We’ll change Bjorn to hold a pointer to the input component instead of having an inline instance:

class Bjorn

{

public:

int velocity;

int x, y;

Bjorn(InputComponent* input)

: input_(input)

{}

void update(World& world, Graphics& graphics)

{

input_->update(*this);

physics_.update(*this, world);

graphics_.update(*this, graphics);

}

private:

InputComponent* input_;

PhysicsComponent physics_;

GraphicsComponent graphics_;

};

Now, when we instantiate Bjorn, we can pass in an input component for it to use, like so:

Bjorn* bjorn = new Bjorn(new PlayerInputComponent());

This instance can be any concrete type that implements our abstract InputComponent interface. We pay a price for this — update() is now a virtual method call, which is a little slower. What do we get in return for this cost?

Most consoles require a game to support “demo mode.” If the player sits at the main menu without doing anything, the game will start playing automatically, with the computer standing in for the player. This keeps the game from burning the main menu into your TV and also makes the game look nicer when it’s running on a kiosk in a store.

Hiding the input component class behind an interface lets us get that working. We already have our concrete PlayerInputComponent that’s normally used when playing the game. Now, let’s make another one:

class DemoInputComponent : public InputComponent

{

public:

virtual void update(Bjorn& bjorn)

{

// AI to automatically control Bjorn...

}

};

When the game goes into demo mode, instead of constructing Bjørn like we did earlier, we’ll wire him up with our new component:

Bjorn* bjorn = new Bjorn(new DemoInputComponent());

And now, just by swapping out a component, we’ve got a fully functioning computer-controlled player for demo mode. We’re able to reuse all of the other code for Bjørn — physics and graphics don’t even know there’s a difference. Maybe I’m a bit strange, but it’s stuff like this that gets me up in the morning.

That, and coffee. Sweet, steaming hot coffee.

No Bjørn at all?

If you look at our Bjorn class now, you’ll notice there’s nothing really “Bjørn” about it — it’s just a component bag. In fact, it looks like a pretty good candidate for a base “game object” class that we can use for every object in the game. All we need to do is pass in all the components, and we can build any kind of object by picking and choosing parts like Dr. Frankenstein.

Let’s take our two remaining concrete components — physics and graphics — and hide them behind interfaces like we did with input:

class PhysicsComponent

{

public:

virtual ~PhysicsComponent() {}

virtual void update(GameObject& obj, World& world) = 0;

};

class GraphicsComponent

{

public:

virtual ~GraphicsComponent() {}

virtual void update(GameObject& obj, Graphics& graphics) = 0;

};

Then we re-christen Bjorn into a generic GameObject class that uses those interfaces:

class GameObject

{

public:

int velocity;

int x, y;

GameObject(InputComponent* input,

PhysicsComponent* physics,

GraphicsComponent* graphics)

: input_(input),

physics_(physics),

graphics_(graphics)

{}

void update(World& world, Graphics& graphics)

{

input_->update(*this);

physics_->update(*this, world);

graphics_->update(*this, graphics);

}

private:

InputComponent* input_;

PhysicsComponent* physics_;

GraphicsComponent* graphics_;

};

Some component systems take this even further. Instead of a GameObject that contains its components, the game entity is just an ID, a number. Then, you maintain separate collections of components where each one knows the ID of the entity its attached to.

These entity component systems take decoupling components to the extreme and let you add new components to an entity without the entity even knowing. The Data Locality chapter has more details.

Our existing concrete classes will get renamed and implement those interfaces:

class BjornPhysicsComponent : public PhysicsComponent

{

public:

virtual void update(GameObject& obj, World& world)

{

// Physics code...

}

};

class BjornGraphicsComponent : public GraphicsComponent

{

public:

virtual void update(GameObject& obj, Graphics& graphics)

{

// Graphics code...

}

};

And now we can build an object that has all of Bjørn’s original behavior without having to actually create a class for him, just like this:

GameObject* createBjorn()

{

return new GameObject(new PlayerInputComponent(),

new BjornPhysicsComponent(),

new BjornGraphicsComponent());

}

This createBjorn() function is, of course, an example of the classic Gang of Four Factory Method pattern.

By defining other functions that instantiate GameObjects with different components, we can create all of the different kinds of objects our game needs.

Design Decisions

The most important design question you’ll need to answer with this pattern is, “What set of components do I need?” The answer there is going to depend on the needs and genre of your game. The bigger and more complex your engine is, the more finely you’ll likely want to slice your components.

Beyond that, there are a couple of more specific options to consider:

How does the object get its components?

Once we’ve split up our monolithic object into a few separate component parts, we have to decide who puts the parts back together.

· If the object creates its own components:

o It ensures that the object always has the components it needs. You never have to worry about someone forgetting to wire up the right components to the object and breaking the game. The container object itself takes care of it for you.

o It’s harder to reconfigure the object. One of the powerful features of this pattern is that it lets you build new kinds of objects simply by recombining components. If our object always wires itself with the same set of hard-coded components, we aren’t taking advantage of that flexibility.

· If outside code provides the components:

o The object becomes more flexible. We can completely change the behavior of the object by giving it different components to work with. Taken to its fullest extent, our object becomes a generic component container that we can reuse over and over again for different purposes.

o The object can be decoupled from the concrete component types. If we’re allowing outside code to pass in components, odds are good that we’re also letting it pass in derived component types. At that point, the object only knows about the component interfaces and not the concrete types themselves. This can make for a nicely encapsulated architecture.

How do components communicate with each other?

Perfectly decoupled components that function in isolation is a nice ideal, but it doesn’t really work in practice. The fact that these components are part of the same object implies that they are part of a larger whole and need to coordinate. That means communication.

So how can the components talk to each other? There are a couple of options, but unlike most design “alternatives” in this book, these aren’t exclusive — you will likely support more than one at the same time in your designs.

· By modifying the container object’s state:

o It keeps the components decoupled. When our InputComponent set Bjørn’s velocity and the PhysicsComponent later used it, the two components had no idea that the other even existed. For all they knew, Bjørn’s velocity could have changed through black magic.

o It requires any information that components need to share to get pushed up into the container object. Often, there’s state that’s really only needed by a subset of the components. For example, an animation and a rendering component may need to share information that’s graphics-specific. Pushing that information up into the container object where every component can get to it muddies the object class.

Worse, if we use the same container object class with different component configurations, we can end up wasting memory on state that isn’t needed by any of the object’s components. If we push some rendering-specific data into the container object, any invisible object will be burning memory on it with no benefit.

o It makes communication implicit and dependent on the order that components are processed. In our sample code, the original monolithic update() method had a very carefully laid out order of operations. The user input modified the velocity, which was then used by the physics code to modify the position, which in turn was used by the rendering code to draw Bjørn at the right spot. When we split that code out into components, we were careful to preserve that order of operations.

If we hadn’t, we would have introduced subtle, hard-to-track bugs. For example, if we’d updated the graphics component first, we would wrongly render Bjørn at his position on the last frame, not this one. If you imagine several more components and lots more code, then you can get an idea of how hard it can be to avoid bugs like this.

Shared mutable state like this where lots of code is reading and writing the same data is notoriously hard to get right. That’s a big part of why academics are spending time researching pure functional languages like Haskell where there is no mutable state at all.

· By referring directly to each other:

The idea here is that components that need to talk will have direct references to each other without having to go through the container object at all.

Let’s say we want to let Bjørn jump. The graphics code needs to know if he should be drawn using a jump sprite or not. It can determine this by asking the physics engine if he’s currently on the ground. An easy way to do this is by letting the graphics component know about the physics component directly:

class BjornGraphicsComponent

{

public:

BjornGraphicsComponent(BjornPhysicsComponent* physics)

: physics_(physics)

{}

void Update(GameObject& obj, Graphics& graphics)

{

Sprite* sprite;

if (!physics_->isOnGround())

{

sprite = &spriteJump_;

}

else

{

// Existing graphics code...

}

graphics.draw(*sprite, obj.x, obj.y);

}

private:

BjornPhysicsComponent* physics_;

Sprite spriteStand_;

Sprite spriteWalkLeft_;

Sprite spriteWalkRight_;

Sprite spriteJump_;

};

When we construct Bjørn’s GraphicsComponent, we’ll give it a reference to his corresponding PhysicsComponent.

o It’s simple and fast. Communication is a direct method call from one object to another. The component can call any method that is supported by the component it has a reference to. It’s a free-for-all.

o The two components are tightly coupled. The downside of the free-for-all. We’ve basically taken a step back towards our monolithic class. It’s not quite as bad as the original single class though, since we’re at least restricting the coupling to only the component pairs that need to interact.

· By sending messages:

o This is the most complex alternative. We can actually build a little messaging system into our container object and let the components broadcast information to each other.

Here’s one possible implementation. We’ll start by defining a base Component interface that all of our components will implement:

class Component

{

public:

virtual ~Component() {}

virtual void receive(int message) = 0;

};

It has a single receive() method that component classes implement in order to listen to an incoming message. Here, we’re just using an int to identify the message, but a fuller implementation could attach additional data to the message.

Then, we’ll add a method to our container object for sending messages:

class ContainerObject

{

public:

void send(int message)

{

for (int i = 0; i < MAX_COMPONENTS; i++)

{

if (components_[i] != NULL)

{

components_[i]->receive(message);

}

}

}

private:

static const int MAX_COMPONENTS = 10;

Component* components_[MAX_COMPONENTS];

};

Now, if a component has access to its container, it can send messages to the container, which will rebroadcast the message to all of the contained components. (That inclues the original component that sent the message; be careful that you don’t get stuck in a feedback loop!) This has a couple of consequences:

If you really want to get fancy, you can even make this message system queue messages to be delivered later. For more on this, see Event Queue.

o Sibling components are decoupled. By going through the parent container object, like our shared state alternative, we ensure that the components are still decoupled from each other. With this system, the only coupling they have is the message values themselves.

The Gang of Four call this the Mediator pattern — two or more objects communicate with each other indirectly by routing the message through an intermediate object. In this case, the container object itself is the mediator.

o The container object is simple. Unlike using shared state where the container object itself owns and knows about data used by the components, here, all it does is blindly pass the messages along. That can be useful for letting two components pass very domain-specific information between themselves without having that bleed into the container object.

Unsurprisingly, there’s no one best answer here. What you’ll likely end up doing is using a bit of all of them. Shared state is useful for the really basic stuff that you can take for granted that every object has — things like position and size.

Some domains are distinct but still closely related. Think animation and rendering, user input and AI, or physics and collision. If you have separate components for each half of those pairs, you may find it easiest to just let them know directly about their other half.

Messaging is useful for “less important” communication. Its fire-and-forget nature is a good fit for things like having an audio component play a sound when a physics component sends a message that the object has collided with something.

As always, I recommend you start simple and then add in additional communication paths if you need them.

See Also

· The Unity framework’s core GameObject class is designed entirely around components.

· The open source Delta3D engine has a base GameActor class that implements this pattern with the appropriately named ActorComponent base class.

· Microsoft’s XNA game framework comes with a core Game class. It owns a collection of GameComponent objects. Where our example uses components at the individual game entity level, XNA implements the pattern at the level of the main game object itself, but the purpose is the same.

· This pattern bears resemblance to the Gang of Four’s Strategy pattern. Both patterns are about taking part of an object’s behavior and delegating it to a separate subordinate object. The difference is that with the Strategy pattern, the separate “strategy” object is usually stateless — it encapsulates an algorithm, but no data. It defines how an object behaves, but not what it is.

Components are a bit more self-important. They often hold state that describes the object and helps define its actual identity. However, the line may blur. You may have some components that don’t need any local state. In that case, you’re free to use the same component instance across multiple container objects. At that point, it really is behaving more akin to a strategy.