Game Programming Patterns (2014)

Optimization Patterns

Dirty Flag

Intent

Avoid unnecessary work by deferring it until the result is needed.

Motivation

Many games have something called a scene graph. This is a big data structure that contains all of the objects in the world. The rendering engine uses this to determine where to draw stuff on the screen.

At its simplest, a scene graph is just a flat list of objects. Each object has a model, or some other graphic primitive, and a transform. The transform describes the object’s position, rotation, and scale in the world. To move or turn an object, we simply change its transform.

The mechanics of how this transform is stored and manipulated are unfortunately out of scope here. The comically abbreviated summary is that it’s a 4x4 matrix. You can make a single transform that combines two transforms — for example, translating and then rotating an object — by multiplying the two matrices.

How and why that works is left as an exercise for the reader.

When the renderer draws an object, it takes the object’s model, applies the transform to it, and then renders it there in the world. If we had a scene bag and not a scene graph, that would be it, and life would be simple.

However, most scene graphs are hierarchical. An object in the graph may have a parent object that it is anchored to. In that case, its transform is relative to the parent’s position and isn’t an absolute position in the world.

For example, imagine our game world has a pirate ship at sea. Atop the ship’s mast is a crow’s nest. Hunched in that crow’s nest is a pirate. Clutching the pirate’s shoulder is a parrot. The ship’s local transform positions the ship in the sea. The crow’s nest’s transform positions the nest on the ship, and so on.

Programmer art!

This way, when a parent object moves, its children move with it automatically. If we change the local transform of the ship, the crow’s nest, pirate, and parrot go along for the ride. It would be a total headache if, when the ship moved, we had to manually adjust the transforms of all the objects on it to keep them from sliding off.

To be honest, when you are at sea you do have to keep manually adjusting your position to keep from sliding off. Maybe I should have chosen a drier example.

But to actually draw the parrot on screen, we need to know its absolute position in the world. I’ll call the parent-relative transform the object’s local transform. To render an object, we need to know its world transform.

Local and world transforms

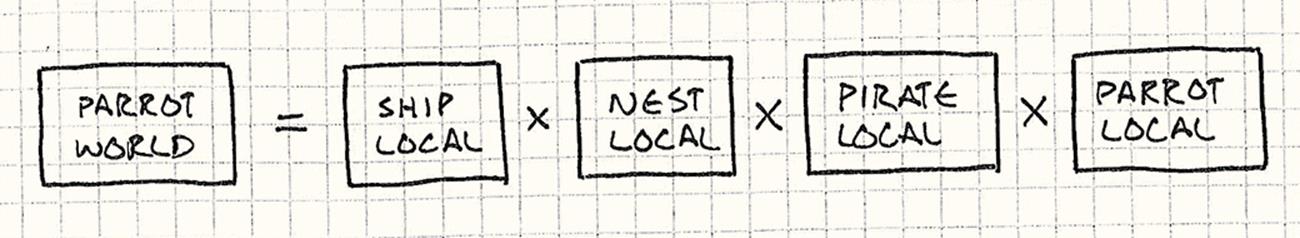

Calculating an object’s world transform is pretty straightforward — you just walk its parent chain starting at the root all the way down to the object, combining transforms as you go. In other words, the parrot’s world transform is:

In the degenerate case where the object has no parent, its local and world transforms are equivalent.

We need the world transform for every object in the world every frame, so even though there are only a handful of matrix multiplications per model, it’s on the hot code path where performance is critical. Keeping them up to date is tricky because when a parent object moves, that affects the world transform of itself and all of its children, recursively.

The simplest approach is to calculate transforms on the fly while rendering. Each frame, we recursively traverse the scene graph starting at the top of the hierarchy. For each object, we calculate its world transform right then and draw it.

But this is terribly wasteful of our precious CPU juice! Many objects in the world are not moving every frame. Think of all of the static geometry that makes up the level. Recalculating their world transforms each frame even though they haven’t changed is a waste.

Cached world transforms

The obvious answer is to cache it. In each object, we store its local transform and its derived world transform. When we render, we only use the precalculated world transform. If the object never moves, the cached transform is always up to date and everything’s happy.

When an object does move, the simple approach is to refresh its world transform right then. But don’t forget the hierarchy! When a parent moves, we have to recalculate its world transform and all of its children’s, recursively.

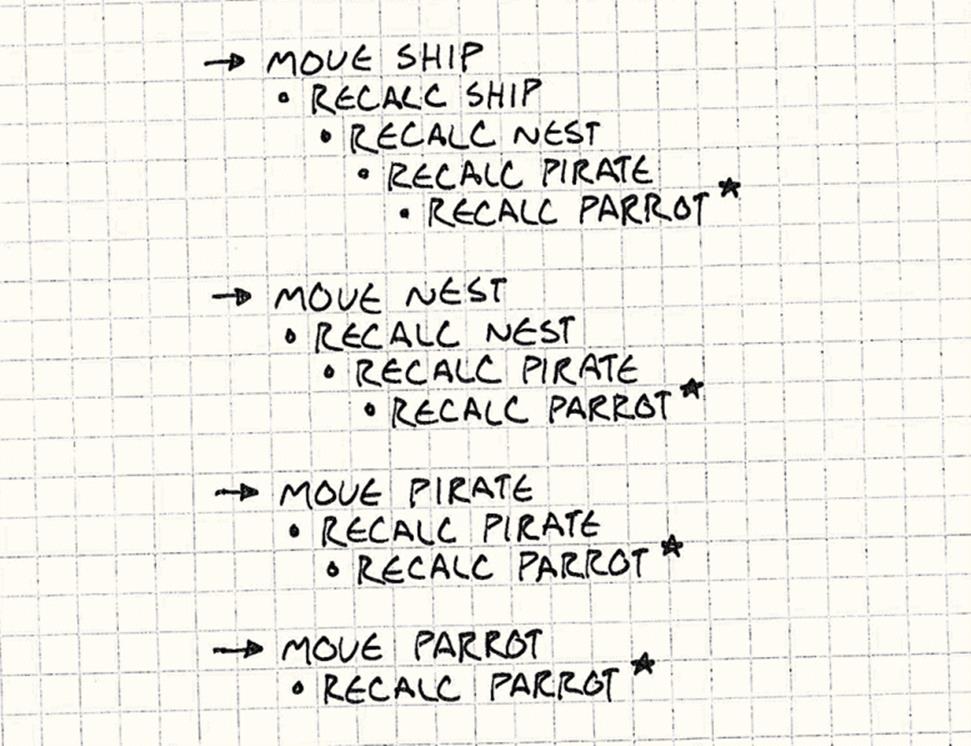

Imagine some busy gameplay. In a single frame, the ship gets tossed on the ocean, the crow’s nest rocks in the wind, the pirate leans to the edge, and the parrot hops onto his head. We changed four local transforms. If we recalculate world transforms eagerly whenever a local transform changes, what ends up happening?

You can see on the lines marked ★ that we’re recalculating the parrot’s world transform four times when we only need the result of the final one.

We only moved four objects, but we did ten world transform calculations. That’s six pointless calculations that get thrown out before they are ever used by the renderer. We calculated the parrot’s world transform four times, but it is only rendered once.

The problem is that a world transform may depend on several local transforms. Since we recalculate immediately each time one of the transforms changes, we end up recalculating the same transform multiple times when more than one of the local transforms it depends on changes in the same frame.

Deferred recalculation

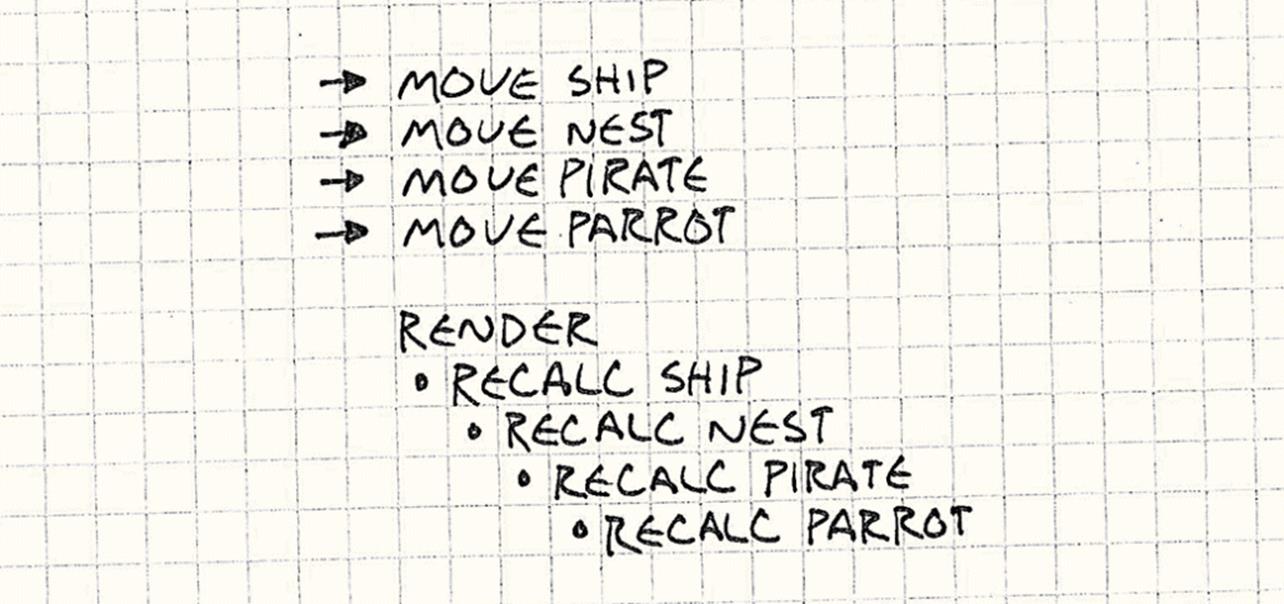

We’ll solve this by decoupling changing local transforms from updating the world transforms. This lets us change a bunch of local transforms in a single batch and then recalculate the affected world transform just once after all of those modifications are done, right before we need it to render.

It’s interesting how much of software architecture is intentionally engineering a little slippage.

To do this, we add a flag to each object in the graph. “Flag” and “bit” are synonymous in programming — they both mean a single micron of data that can be in one of two states. We call those “true” and “false”, or sometimes “set” and “cleared”. I’ll use all of these interchangeably.

When the local transform changes, we set it. When we need the object’s world transform, we check the flag. If it’s set, we calculate the world transform and then clear the flag. The flag represents, “Is the world transform out of date?” For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, the traditional name for this “out-of-date-ness” is “dirty”. Hence: a dirty flag. “Dirty bit” is an equally common name for this pattern, but I figured I’d stick with the name that didn’t seem as prurient.

Wikipedia’s editors don’t have my level of self-control and went with dirty bit.

If we apply this pattern and then move all of the objects in our previous example, the game ends up doing:

That’s the best you could hope to do — the world transform for each affected object is calculated exactly once. With only a single bit of data, this pattern does a few things for us:

· It collapses modifications to multiple local transforms along an object’s parent chain into a single recalculation on the object.

· It avoids recalculation on objects that didn’t move.

· And a minor bonus: if an object gets removed before it’s rendered, it doesn’t calculate its world transform at all.

The Pattern

A set of primary data changes over time. A set of derived data is determined from this using some expensive process. A “dirty” flag tracks when the derived data is out of sync with the primary data. It is set when the primary data changes. If the flag is set when the derived data is needed, then it is reprocessed and the flag is cleared. Otherwise, the previous cached derived data is used.

When to Use It

Compared to some other patterns in this book, this one solves a pretty specific problem. Also, like most optimizations, you should only reach for it when you have a performance problem big enough to justify the added code complexity.

Dirty flags are applied to two kinds of work: calculation and synchronization. In both cases, the process of going from the primary data to the derived data is time-consuming or otherwise costly.

In our scene graph example, the process is slow because of the amount of math to perform. When using this pattern for synchronization, on the other hand, it’s more often that the derived data is somewhere else — either on disk or over the network on another machine — and simply getting it from point A to point B is what’s expensive.

There are a couple of other requirements too:

· The primary data has to change more often than the derived data is used. This pattern works by avoiding processing derived data when a subsequent primary data change would invalidate it before it gets used. If you find yourself always needing that derived data after every single modification to the primary data, this pattern can’t help.

· It should be hard to update incrementally. Let’s say the pirate ship in our game can only carry so much booty. We need to know the total weight of everything in the hold. We could use this pattern and have a dirty flag for the total weight. Every time we add or remove some loot, we set the flag. When we need the total, we add up all of the booty and clear the flag.

But a simpler solution is to keep a running total. When we add or remove an item, just add or remove its weight from the current total. If we can “pay as we go” like this and keep the derived data updated, then that’s often a better choice than using this pattern and calculating the derived data from scratch when needed.

This makes it sound like dirty flags are rarely appropriate, but you’ll find a place here or there where they help. Searching your average game codebase for the word “dirty” will often turn up uses of this pattern.

From my research, it also turns up a lot of comments apologizing for “dirty” hacks.

Keep in Mind

Even after you’ve convinced yourself this pattern is a good fit, there are a few wrinkles that can cause you some discomfort.

There is a cost to deferring for too long

This pattern defers some slow work until the result is actually needed, but when it is, it’s often needed right now. But the reason we’re using this pattern to begin with is because calculating that result is slow!

This isn’t a problem in our example because we can still calculate world coordinates fast enough to fit within a frame, but you can imagine other cases where the work you’re doing is a big chunk that takes noticeable time to chew through. If the game doesn’t start chewing until right when the player expects to see the result, that can cause an unpleasant visible pause.

Another problem with deferring is that if something goes wrong, you may fail to do the work at all. This can be particularly problematic when you’re using this pattern to save some state to a more persistent form.

For example, text editors know if your document has “unsaved changes”. That little bullet or star in your file’s title bar is literally the dirty flag visualized. The primary data is the open document in memory, and the derived data is the file on disk.

Many programs don’t save to disk until either the document is closed or the application is exited. That’s fine most of the time, but if you accidentally kick the power cable out, there goes your masterpiece.

Editors that auto-save a backup in the background are compensating specifically for this shortcoming. The auto-save frequency is a point on the continuum between not losing too much work when a crash occurs and not thrashing the file system too much by saving all the time.

This mirrors the different garbage collection strategies in systems that automatically manage memory. Reference counting frees memory the second it’s no longer needed, but it burns CPU time updating ref counts eagerly every time references are changed.

Simple garbage collectors defer reclaiming memory until it’s really needed, but the cost is the dreaded “GC pause” that can freeze your entire game until the collector is done scouring the heap.

In between the two are more complex systems like deferred ref-counting and incremental GC that reclaim memory less eagerly than pure ref-counting but more eagerly than stop-the-world collectors.

You have to make sure to set the flag every time the state changes

Since the derived data is calculated from the primary data, it’s essentially a cache. Whenever you have cached data, the trickiest aspect of it is cache invalidation — correctly noting when the cache is out of sync with its source data. In this pattern, that means setting the dirty flag when anyprimary data changes.

Phil Karlton famously said, “There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.”

Miss it in one place, and your program will incorrectly use stale derived data. This leads to confused players and bugs that are very hard to track down. When you use this pattern, you’ll have to take care that any code that modifies the primary state also sets the dirty flag.

One way to mitigate this is by encapsulating modifications to the primary data behind some interface. If anything that can change the state goes through a single narrow API, you can set the dirty flag there and rest assured that it won’t be missed.

You have to keep the previous derived data in memory

When the derived data is needed and the dirty flag isn’t set, it uses the previously calculated data. This is obvious, but that does imply that you have to keep that derived data around in memory in case you end up needing it later.

This isn’t much of an issue when you’re using this pattern to synchronize the primary state to some other place. In that case, the derived data isn’t usually in memory at all.

If you weren’t using this pattern, you could calculate the derived data on the fly whenever you needed it, then discard it when you were done. That avoids the expense of keeping it cached in memory at the cost of having to do that calculation every time you need the result.

Like many optimizations, then, this pattern trades memory for speed. In return for keeping the previously calculated data in memory, you avoid having to recalculate it when it hasn’t changed. This trade-off makes sense when the calculation is slow and memory is cheap. When you’ve got more time than memory on your hands, it’s better to calculate it as needed.

Conversely, compression algorithms make the opposite trade-off: they optimize space at the expense of the processing time needed to decompress.

Sample Code

Let’s assume we’ve met the surprisingly long list of requirements and see how the pattern looks in code. As I mentioned before, the actual math behind transform matrices is beyond the humble aims of this book, so I’ll just encapsulate that in a class whose implementation you can presume exists somewhere out in the æther:

class Transform

{

public:

static Transform origin();

Transform combine(Transform& other);

};

The only operation we need here is combine() so that we can get an object’s world transform by combining all of the local transforms along its parent chain. It also has a method to get an “origin” transform — basically an identity matrix that means no translation, rotation, or scaling at all.

Next, we’ll sketch out the class for an object in the scene graph. This is the bare minimum we need before applying this pattern:

class GraphNode

{

public:

GraphNode(Mesh* mesh)

: mesh_(mesh),

local_(Transform::origin())

{}

private:

Transform local_;

Mesh* mesh_;

GraphNode* children_[MAX_CHILDREN];

int numChildren_;

};

Each node has a local transform which describes where it is relative to its parent. It has a mesh which is the actual graphic for the object. (We’ll allow mesh_ to be NULL too to handle non-visual nodes that are used just to group their children.) Finally, each node has a possibly empty collection of child nodes.

With this, a “scene graph” is really only a single root GraphNode whose children (and grandchildren, etc.) are all of the objects in the world:

GraphNode* graph_ = new GraphNode(NULL);

// Add children to root graph node...

In order to render a scene graph, all we need to do is traverse that tree of nodes, starting at the root, and call the following function for each node’s mesh with the right world transform:

void renderMesh(Mesh* mesh, Transform transform);

We won’t implement this here, but if we did, it would do whatever magic the renderer needs to draw that mesh at the given location in the world. If we can call that correctly and efficiently on every node in the scene graph, we’re happy.

An unoptimized traversal

To get our hands dirty, let’s throw together a basic traversal for rendering the scene graph that calculates the world positions on the fly. It won’t be optimal, but it will be simple. We’ll add a new method to GraphNode:

void GraphNode::render(Transform parentWorld)

{

Transform world = local_.combine(parentWorld);

if (mesh_) renderMesh(mesh_, world);

for (int i = 0; i < numChildren_; i++)

{

children_[i]->render(world);

}

}

We pass the world transform of the node’s parent into this using parentWorld. With that, all that’s left to get the correct world transform of this node is to combine that with its own local transform. We don’t have to walk up the parent chain to calculate world transforms because we calculate as we go while walking down the chain.

We calculate the node’s world transform and store it in world, then we render the mesh, if we have one. Finally, we recurse into the child nodes, passing in this node’s world transform. All in all, it’s a tight, simple recursive method.

To draw an entire scene graph, we kick off the process at the root node:

graph_->render(Transform::origin());

Let’s get dirty

So this code does the right thing — it renders all the meshes in the right place — but it doesn’t do it efficiently. It’s calling local_.combine(parentWorld) on every node in the graph, every frame. Let’s see how this pattern fixes that. First, we need to add two fields to GraphNode:

class GraphNode

{

public:

GraphNode(Mesh* mesh)

: mesh_(mesh),

local_(Transform::origin()),

dirty_(true)

{}

// Other methods...

private:

Transform world_;

bool dirty_;

// Other fields...

};

The world_ field caches the previously calculated world transform, and dirty_, of course, is the dirty flag. Note that the flag starts out true. When we create a new node, we haven’t calculated its world transform yet. At birth, it’s already out of sync with the local transform.

The only reason we need this pattern is because objects can move, so let’s add support for that:

void GraphNode::setTransform(Transform local)

{

local_ = local;

dirty_ = true;

}

The important part here is that it sets the dirty flag too. Are we forgetting anything? Right — the child nodes!

When a parent node moves, all of its children’s world coordinates are invalidated too. But here, we aren’t setting their dirty flags. We could do that, but that’s recursive and slow. Instead, we’ll do something clever when we go to render. Let’s see:

void GraphNode::render(Transform parentWorld, bool dirty)

{

dirty |= dirty_;

if (dirty)

{

world_ = local_.combine(parentWorld);

dirty_ = false;

}

if (mesh_) renderMesh(mesh_, world_);

for (int i = 0; i < numChildren_; i++)

{

children_[i]->render(world_, dirty);

}

}

There’s a subtle assumption here that the if check is faster than a matrix multiply. Intuitively, you would think it is; surely testing a single bit is faster than a bunch of floating point arithmetic.

However, modern CPUs are fantastically complex. They rely heavily on pipelining — queueing up a series of sequential instructions. A branch like our if here can cause a branch misprediction and force the CPU to lose cycles refilling the pipeline.

The Data Locality chapter has more about how modern CPUs try to go faster and how you can avoid tripping them up like this.

This is similar to the original naïve implementation. The key changes are that we check to see if the node is dirty before calculating the world transform and we store the result in a field instead of a local variable. When the node is clean, we skip combine() completely and use the old-but-still-correct world_ value.

The clever bit is that dirty parameter. That will be true if any node above this node in the parent chain was dirty. In much the same way that parentWorld updates the world transform incrementally as we traverse down the hierarchy, dirty tracks the dirtiness of the parent chain.

This lets us avoid having to recursively mark each child’s dirty_ flag in setTransform(). Instead, we pass the parent’s dirty flag down to its children when we render and look at that too to see if we need to recalculate the world transform.

The end result here is exactly what we want: changing a node’s local transform is just a couple of assignments, and rendering the world calculates the exact minimum number of world transforms that have changed since the last frame.

Note that this clever trick only works because render() is the only thing in GraphNode that needs an up-to-date world transform. If other things accessed it, we’d have to do something different.

Design Decisions

This pattern is fairly specific, so there are only a couple of knobs to twiddle:

When is the dirty flag cleaned?

· When the result is needed:

o It avoids doing calculation entirely if the result is never used. For primary data that changes much more frequently than the derived data is accessed, this can be a big win.

o If the calculation is time-consuming, it can cause a noticeable pause. Postponing the work until the player is expecting to see the result can affect their gameplay experience. It’s often fast enough that this isn’t a problem, but if it is, you’ll have to do the work earlier.

· At well-defined checkpoints:

Sometimes, there is a point in time or in the progression of the game where it’s natural to do the deferred processing. For example, we may want to save the game only when the pirate sails into port. Or the sync point may not be part of the game mechanics. We may just want to hide the work behind a loading screen or a cut scene.

o Doing the work doesn’t impact the user experience. Unlike the previous option, you can often give something to distract the player while the game is busy processing.

o You lose control over when the work happens. This is sort of the opposite of the earlier point. You have micro-scale control over when you process, and can make sure the game handles it gracefully.

What you can’t do is ensure the player actually makes it to the checkpoint or meets whatever criteria you’ve defined. If they get lost or the game gets in a weird state, you can end up deferring longer than you expect.

· In the background:

Usually, you start a fixed timer on the first modification and then process all of the changes that happen between then and when the timer fires.

The term in human-computer interaction for an intentional delay between when a program receives user input and when it responds is hysteresis.

o You can tune how often the work is performed. By adjusting the timer interval, you can ensure it happens as frequently (or infrequently) as you want.

o You can do more redundant work. If the primary state only changes a tiny amount during the timer’s run, you can end up processing a large chunk of mostly unchanged data.

o You need support for doing work asynchronously. Processing the data “in the background” implies that the player can keep doing whatever it is that they’re doing at the same time. That means you’ll likely need threading or some other kind of concurrency support so that the game can work on the data while it’s still being played.

Since the player is likely interacting with the same primary state that you’re processing, you’ll need to think about making that safe for concurrent modification too.

How fine-grained is your dirty tracking?

Imagine our pirate game lets players build and customize their pirate ship. Ships are automatically saved online so the player can resume where they left off. We’re using dirty flags to determine which decks of the ship have been fitted and need to be sent to the server. Each chunk of data we send to the server contains some modified ship data and a bit of metadata describing where on the ship this modification occurred.

· If it’s more fine-grained:

Say you slap a dirty flag on each tiny plank of each deck.

o You only process data that actually changed. You’ll send exactly the facets of the ship that were modified to the server.

· If it’s more coarse-grained:

Alternatively, we could associate a dirty bit with each deck. Changing anything on it marks the entire deck dirty.

I could make some terrible joke about it needing to be swabbed here, but I’ll refrain.

o You end up processing unchanged data. Add a single barrel to a deck and you’ll have to send the whole thing to the server.

o Less memory is used for storing dirty flags. Add ten barrels to a deck and you only need a single bit to track them all.

o Less time is spent on fixed overhead. When processing some changed data, there’s often a bit of fixed work you have to do on top of handling the data itself. In the example here, that’s the metadata required to identify where on the ship the changed data is. The bigger your processing chunks, the fewer of them there are, which means the less overhead you have.

See Also

· This pattern is common outside of games in browser-side web frameworks like Angular. They use dirty flags to track which data has been changed in the browser and needs to be pushed up to the server.

· Physics engines track which objects are in motion and which are resting. Since a resting body won’t move until an impulse is applied to it, they don’t need processing until they get touched. This “is moving” bit is a dirty flag to note which objects have had forces applied and need to have their physics resolved.