The Go Programming Language (2016)

13. Low-Level Programming

The design of Go guarantees a number of safety properties that limit the ways in which a Go program can “go wrong.” During compilation, type checking detects most attempts to apply an operation to a value that is inappropriate for its type, for instance, subtracting one string from another.Strict rules for type conversions prevent direct access to the internals of built-in types like strings, maps, slices, and channels.

For errors that cannot be detected statically, such as out-of-bounds array accesses or nil pointer dereferences, dynamic checks ensure that the program immediately terminates with an informative error whenever a forbidden operation occurs. Automatic memory management (garbagecollection) eliminates “use after free” bugs, as well as most memory leaks.

Many implementation details are inaccessible to Go programs. There is no way to discover the memory layout of an aggregate type like a struct, or the machine code for a function, or the identity of the operating system thread on which the current goroutine is running. Indeed, the Go scheduler freely moves goroutines from one thread to another. A pointer identifies a variable without revealing the variable’s numeric address. Addresses may change as the garbage collector moves variables; pointers are transparently updated.

Together, these features make Go programs, especially failing ones, more predictable and less mysterious than programs in C, the quintessential low-level language. By hiding the underlying details, they also make Go programs highly portable, since the language semantics are largely independent of any particular compiler, operating system, or CPU architecture. (Not entirely independent: some details leak through, such as the word size of the processor, the order of evaluation of certain expressions, and the set of implementation restrictions imposed by the compiler.)

Occasionally, we may choose to forfeit some of these helpful guarantees to achieve the highest possible performance, to interoperate with libraries written in other languages, or to implement a function that cannot be expressed in pure Go.

In this chapter, we’ll see how the unsafe package lets us step outside the usual rules, and how to use the cgo tool to create Go bindings for C libraries and operating system calls.

The approaches described in this chapter should not be used frivolously. Without careful attention to detail, they may cause the kinds of unpredictable, inscrutable, non-local failures with which C programmers are unhappily acquainted. Use of unsafe also voids Go’s warranty of compatibility with future releases, since, whether intended or inadvertent, it is easy to depend on unspecified implementation details that may change unexpectedly.

The unsafe package is rather magical. Although it appears to be a regular package and is imported in the usual way, it is actually implemented by the compiler. It provides access to a number of built-in language features that are not ordinarily available because they expose details of Go’s memory layout. Presenting these features as a separate package makes the rare occasions on which they are needed more conspicuous. Also, some environments may restrict the use of the unsafe package for security reasons.

Package unsafe is used extensively within low-level packages like runtime, os, syscall, and net that interact with the operating system, but is almost never needed by ordinary programs.

13.1 unsafe.Sizeof, Alignof, and Offsetof

The unsafe.Sizeof function reports the size in bytes of the representation of its operand, which may be an expression of any type; the expression is not evaluated. A call to Sizeof is a constant expression of type uintptr, so the result may be used as the dimension of an array type, or to compute other constants.

import "unsafe"

fmt.Println(unsafe.Sizeof(float64(0))) // "8"

Sizeof reports only the size of the fixed part of each data structure, like the pointer and length of a string, but not indirect parts like the contents of the string. Typical sizes for all non-aggregate Go types are shown below, though the exact sizes may vary by toolchain. For portability, we’ve given the sizes of reference types (or types containing references) in terms of words, where a word is 4 bytes on a 32-bit platform and 8 bytes on a 64-bit platform.

Computers load and store values from memory most efficiently when those values are properly aligned. For example, the address of a value of a two-byte type such as int16 should be an even number, the address of a four-byte value such as a rune should be a multiple of four, and the address of an eight-byte value such as a float64, uint64, or 64-bit pointer should be a multiple of eight. Alignment requirements of higher multiples are unusual, even for larger data types such as complex128.

For this reason, the size of a value of an aggregate type (a struct or array) is at least the sum of the sizes of its fields or elements but may be greater due to the presence of “holes.” Holes are unused spaces added by the compiler to ensure that the following field or element is properly aligned relative to the start of the struct or array.

|

Type |

Size |

|

bool |

1 byte |

|

intN, uintN, floatN, complexN |

N / 8 bytes (for example, float64 is 8 bytes) |

|

int, uint, uintptr |

1 word |

|

*T |

1 word |

|

string |

2 words (data, len) |

|

[]T |

3 words (data, len, cap) |

|

map |

1 word |

|

func |

1 word |

|

chan |

1 word |

|

interface |

2 words (type, value) |

The language specification does not guarantee that the order in which fields are declared is the order in which they are laid out in memory, so in theory a compiler is free to rearrange them, although as we write this, none do. If the types of a struct’s fields are of different sizes, it may be more space-efficient to declare the fields in an order that packs them as tightly as possible. The three structs below have the same fields, but the first requires up to 50% more memory than the other two:

// 64-bit 32-bit

struct{ bool; float64; int16 } // 3 words 4 words

struct{ float64; int16; bool } // 2 words 3 words

struct{ bool; int16; float64 } // 2 words 3 words

The details of the alignment algorithm are beyond the scope of this book, and it’s certainly not worth worrying about every struct, but efficient packing may make frequently allocated data structures more compact and therefore faster.

The unsafe.Alignof function reports the required alignment of its argument’s type. Like Sizeof, it may be applied to an expression of any type, and it yields a constant. Typically, boolean and numeric types are aligned to their size (up to a maximum of 8 bytes) and all other types are word-aligned.

The unsafe.Offsetof function, whose operand must be a field selector x.f, computes the offset of field f relative to the start of its enclosing struct x, accounting for holes, if any.

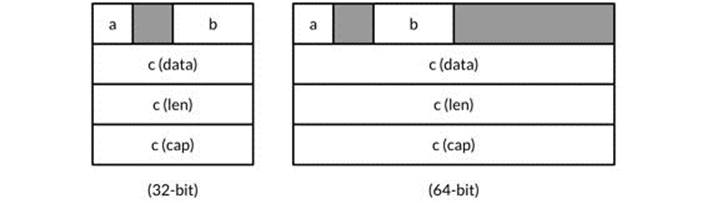

Figure 13.1 shows a struct variable x and its memory layout on typical 32- and 64-bit Go implementations. The gray regions are holes.

var x struct {

a bool

b int16

c []int

}

Figure 13.1. Holes in a struct.

The table below shows the results of applying the three unsafe functions to x itself and to each of its three fields:

Typical 32-bit platform:

Sizeof(x) = 16 Alignof(x) = 4

Sizeof(x.a) = 1 Alignof(x.a) = 1 Offsetof(x.a) = 0

Sizeof(x.b) = 2 Alignof(x.b) = 2 Offsetof(x.b) = 2

Sizeof(x.c) = 12 Alignof(x.c) = 4 Offsetof(x.c) = 4

Typical 64-bit platform:

Sizeof(x) = 32 Alignof(x) = 8

Sizeof(x.a) = 1 Alignof(x.a) = 1 Offsetof(x.a) = 0

Sizeof(x.b) = 2 Alignof(x.b) = 2 Offsetof(x.b) = 2

Sizeof(x.c) = 24 Alignof(x.c) = 8 Offsetof(x.c) = 8

Despite their names, these functions are not in fact unsafe, and they may be helpful for understanding the layout of raw memory in a program when optimizing for space.

13.2 unsafe.Pointer

Most pointer types are written *T, meaning “a pointer to a variable of type T.” The unsafe.Pointer type is a special kind of pointer that can hold the address of any variable. Of course, we can’t indirect through an unsafe.Pointer using *p because we don’t know what type that expression should have. Like ordinary pointers, unsafe.Pointers are comparable and may be compared with nil, which is the zero value of the type.

An ordinary *T pointer may be converted to an unsafe.Pointer, and an unsafe.Pointer may be converted back to an ordinary pointer, not necessarily of the same type *T. By converting a *float64 pointer to a *uint64, for instance, we can inspect the bit pattern of a floating-point variable:

package math

func Float64bits(f float64) uint64 { return *(*uint64)(unsafe.Pointer(&f)) }

fmt.Printf("%#016x\n", Float64bits(1.0)) // "0x3ff0000000000000"

Through the resulting pointer, we can update the bit pattern too. This is harmless for a floating-point variable since any bit pattern is legal, but in general, unsafe.Pointer conversions let us write arbitrary values to memory and thus subvert the type system.

An unsafe.Pointer may also be converted to a uintptr that holds the pointer’s numeric value, letting us perform arithmetic on addresses. (Recall from Chapter 3 that a uintptr is an unsigned integer wide enough to represent an address.) This conversion too may be applied in reverse, but again, converting from a uintptr to an unsafe.Pointer may subvert the type system since not all numbers are valid addresses.

Many unsafe.Pointer values are thus intermediaries for converting ordinary pointers to raw numeric addresses and back again. The example below takes the address of variable x, adds the offset of its b field, converts the resulting address to *int16, and through that pointer updatesx.b:

gopl.io/ch13/unsafeptr

var x struct {

a bool

b int16

c []int

}

// equivalent to pb := &x.b

pb := (*int16)(unsafe.Pointer(

uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&x)) + unsafe.Offsetof(x.b)))

*pb = 42

fmt.Println(x.b) // "42"

Although the syntax is cumbersome—perhaps no bad thing since these features should be used sparingly—do not be tempted to introduce temporary variables of type uintptr to break the lines. This code is incorrect:

// NOTE: subtly incorrect!

tmp := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&x)) + unsafe.Offsetof(x.b)

pb := (*int16)(unsafe.Pointer(tmp))

*pb = 42

The reason is very subtle. Some garbage collectors move variables around in memory to reduce fragmentation or bookkeeping. Garbage collectors of this kind are known as moving GCs. When a variable is moved, all pointers that hold the address of the old location must be updated to point to the new one. From the perspective of the garbage collector, an unsafe.Pointer is a pointer and thus its value must change as the variable moves, but a uintptr is just a number so its value must not change. The incorrect code above hides a pointer from the garbage collector in the non-pointer variable tmp. By the time the second statement executes, the variable x could have moved and the number in tmp would no longer be the address &x.b. The third statement clobbers an arbitrary memory location with the value 42.

There are myriad pathological variations on this theme. After this statement has executed:

pT := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(new(T))) // NOTE: wrong!

there are no pointers that refer to the variable created by new, so the garbage collector is entitled to recycle its storage when this statement completes, after which pT contains the address where the variable was but is no longer.

No current Go implementation uses a moving garbage collector (though future implementations might), but this is no reason for complacency: current versions of Go do move some variables around in memory. Recall from Section 5.2 that goroutine stacks grow as needed. When this happens, all variables on the old stack may be relocated to a new, larger stack, so we cannot rely on the numeric value of a variable’s address remaining unchanged throughout its lifetime.

At the time of writing, there is little clear guidance on what Go programmers may rely upon after an unsafe.Pointer to uintptr conversion (see Go issue 7192), so we strongly recommend that you assume the bare minimum. Treat all uintptr values as if they contain the formeraddress of a variable, and minimize the number of operations between converting an unsafe.Pointer to a uintptr and using that uintptr. In our first example above, the three operations—conversion to a uintptr, addition of the field offset, conversion back—all appeared within a single expression.

When calling a library function that returns a uintptr, such as those below from the reflect package, the result should be immediately converted to an unsafe.Pointer to ensure that it continues to point to the same variable.

package reflect

func (Value) Pointer() uintptr

func (Value) UnsafeAddr() uintptr

func (Value) InterfaceData() [2]uintptr // (index 1)

13.3 Example: Deep Equivalence

The DeepEqual function from the reflect package reports whether two values are “deeply” equal. DeepEqual compares basic values as if by the built-in == operator; for composite values, it traverses them recursively, comparing corresponding elements. Because it works for any pair of values, even ones that are not comparable with ==, it finds widespread use in tests. The following test uses DeepEqual to compare two []string values:

func TestSplit(t *testing.T) {

got := strings.Split("a:b:c", ":")

want := []string{"a", "b", "c"};

if !reflect.DeepEqual(got, want) { /* ... */ }

}

Although DeepEqual is convenient, its distinctions can seem arbitrary. For example, it doesn’t consider a nil map equal to a non-nil empty map, nor a nil slice equal to a non-nil empty one:

var a, b []string = nil, []string{}

fmt.Println(reflect.DeepEqual(a, b)) // "false"

var c, d map[string]int = nil, make(map[string]int)

fmt.Println(reflect.DeepEqual(c, d)) // "false"

In this section we’ll define a function Equal that compares arbitrary values. Like DeepEqual, it compares slices and maps based on their elements, but unlike DeepEqual, it considers a nil slice (or map) equal to a non-nil empty one. The basic recursion over the arguments can be done with reflection, using a similar approach to the Display program we saw in Section 12.3. As usual, we define an unexported function, equal, for the recursion. Don’t worry about the seen parameter just yet. For each pair of values x and y to be compared, equal checks that both (or neither) are valid and checks that they have the same type. The result of the function is defined as a set of switch cases that compare two values of the same type. For reasons of space, we’ve omitted several cases since the pattern should be familiar by now.

gopl.io/ch13/equal

func equal(x, y reflect.Value, seen map[comparison]bool) bool {

if !x.IsValid() || !y.IsValid() {

return x.IsValid() == y.IsValid()

}

if x.Type() != y.Type() {

return false

}

// ...cycle check omitted (shown later)...

switch x.Kind() {

case reflect.Bool:

return x.Bool() == y.Bool()

case reflect.String:

return x.String() == y.String()

// ...numeric cases omitted for brevity...

case reflect.Chan, reflect.UnsafePointer, reflect.Func:

return x.Pointer() == y.Pointer()

case reflect.Ptr, reflect.Interface:

return equal(x.Elem(), y.Elem(), seen)

case reflect.Array, reflect.Slice:

if x.Len() != y.Len() {

return false

}

for i := 0; i < x.Len(); i++ {

if !equal(x.Index(i), y.Index(i), seen) {

return false

}

}

return true

// ...struct and map cases omitted for brevity...

}

panic("unreachable")

}

As usual, we don’t expose the use of reflection in the API, so the exported function Equal must call reflect.ValueOf on its arguments:

// Equal reports whether x and y are deeply equal.

func Equal(x, y interface{}) bool {

seen := make(map[comparison]bool)

return equal(reflect.ValueOf(x), reflect.ValueOf(y), seen)

}

type comparison struct {

x, y unsafe.Pointer

t reflect.Type

}

To ensure that the algorithm terminates even for cyclic data structures, it must record which pairs of variables it has already compared and avoid comparing them a second time. Equal allocates a set of comparison structs, each holding the address of two variables (represented asunsafe.Pointer values) and the type of the comparison. We need to record the type in addition to the addresses because different variables can have the same address. For example, if x and y are both arrays, x and x[0] have the same address, as do y and y[0], and it is important to distinguish whether we have compared x and y or x[0] and y[0].

Once equal has established that its arguments have the same type, and before it executes the switch, it checks whether it is comparing two variables it has already seen and, if so, terminates the recursion.

// cycle check

if x.CanAddr() && y.CanAddr() {

xptr := unsafe.Pointer(x.UnsafeAddr())

yptr := unsafe.Pointer(y.UnsafeAddr())

if xptr == yptr {

return true // identical references

}

c := comparison{xptr, yptr, x.Type()}

if seen[c] {

return true // already seen

}

seen[c] = true

}

Here’s our Equal function in action:

fmt.Println(Equal([]int{1, 2, 3}, []int{1, 2, 3})) // "true"

fmt.Println(Equal([]string{"foo"}, []string{"bar"})) // "false"

fmt.Println(Equal([]string(nil), []string{})) // "true"

fmt.Println(Equal(map[string]int(nil), map[string]int{})) // "true"

It even works on cyclic inputs similar to the one that caused the Display function from Section 12.3 to get stuck in a loop:

// Circular linked lists a -> b -> a and c -> c.

type link struct {

value string

tail *link

}

a, b, c := &link{value: "a"}, &link{value: "b"}, &link{value: "c"}

a.tail, b.tail, c.tail = b, a, c

fmt.Println(Equal(a, a)) // "true"

fmt.Println(Equal(b, b)) // "true"

fmt.Println(Equal(c, c)) // "true"

fmt.Println(Equal(a, b)) // "false"

fmt.Println(Equal(a, c)) // "false"

Exercise 13.1: Define a deep comparison function that considers numbers (of any type) equal if they differ by less than one part in a billion.

Exercise 13.2: Write a function that reports whether its argument is a cyclic data structure.

13.4 Calling C Code with cgo

A Go program might need to use a hardware driver implemented in C, query an embedded database implemented in C++, or use some linear algebra routines implemented in Fortran. C has long been the lingua franca of programming, so many packages intended for widespread use export a C-compatible API, regardless of the language of their implementation.

In this section, we’ll build a simple data compression program that uses cgo, a tool that creates Go bindings for C functions. Such tools are called foreign-function interfaces (FFIs), and cgo is not the only one for Go programs. SWIG (swig.org) is another; it provides more complex features for integrating with C++ classes, but we won’t show it here.

The compress/... subtree of the standard library provides compressors and decompressors for popular compression algorithms, including LZW (used by the Unix compress command) and DEFLATE (used by the GNU gzip command). The APIs of these packages vary slightly in details, but they all provide a wrapper for an io.Writer that compresses the data written to it, and a wrapper for an io.Reader that decompresses the data read from it. For example:

package gzip // compress/gzip

func NewWriter(w io.Writer) io.WriteCloser

func NewReader(r io.Reader) (io.ReadCloser, error)

The bzip2 algorithm, which is based on the elegant Burrows-Wheeler transform, runs slower than gzip but yields significantly better compression. The compress/bzip2 package provides a decompressor for bzip2, but at the moment the package provides no compressor. Building one from scratch is a substantial undertaking, but there is a well-documented and high-performance open-source C implementation, the libbzip2 package from bzip.org.

If the C library were small, we would just port it to pure Go, and if its performance were not critical for our purposes, we would be better off invoking a C program as a helper subprocess using the os/exec package. It’s when you need to use a complex, performance-critical library with a narrow C API that it may make sense to wrap it using cgo. For the rest of this chapter, we’ll work through an example.

From the libbzip2 C package, we need the bz_stream struct type, which holds the input and output buffers, and three C functions: BZ2_bzCompressInit, which allocates the stream’s buffers; BZ2_bzCompress, which compresses data from the input buffer to the output buffer; and BZ2_bzCompressEnd, which releases the buffers. (Don’t worry about the mechanics of the libbzip2 package; the purpose of this example is to show how the parts fit together.)

We’ll call the BZ2_bzCompressInit and BZ2_bzCompressEnd C functions directly from Go, but for BZ2_bzCompress, we’ll define a wrapper function in C, to show how it’s done. The C source file below lives alongside the Go code in our package:

gopl.io/ch13/bzip

/* This file is gopl.io/ch13/bzip/bzip2.c, */

/* a simple wrapper for libbzip2 suitable for cgo. */

#include <bzlib.h>

int bz2compress(bz_stream *s, int action,

char *in, unsigned *inlen, char *out, unsigned *outlen) {

s->next_in = in;

s->avail_in = *inlen;

s->next_out = out;

s->avail_out = *outlen;

int r = BZ2_bzCompress(s, action);

*inlen -= s->avail_in;

*outlen -= s->avail_out;

return r;

}

Now let’s turn to the Go code, the first part of which is shown below. The import "C" declaration is special. There is no package C, but this import causes go build to preprocess the file using the cgo tool before the Go compiler sees it.

// Package bzip provides a writer that uses bzip2 compression (bzip.org).

package bzip

/*

#cgo CFLAGS: -I/usr/include

#cgo LDFLAGS: -L/usr/lib -lbz2

#include <bzlib.h>

int bz2compress(bz_stream *s, int action,

char *in, unsigned *inlen, char *out, unsigned *outlen);

*/

import "C"

import (

"io"

"unsafe"

)

type writer struct {

w io.Writer // underlying output stream

stream *C.bz_stream

outbuf [64 * 1024]byte

}

// NewWriter returns a writer for bzip2-compressed streams.

func NewWriter(out io.Writer) io.WriteCloser {

const (

blockSize = 9

verbosity = 0

workFactor = 30

)

w := &writer{w: out, stream: new(C.bz_stream)}

C.BZ2_bzCompressInit(w.stream, blockSize, verbosity, workFactor)

return w

}

During preprocessing, cgo generates a temporary package that contains Go declarations corresponding to all the C functions and types used by the file, such as C.bz_stream and C.BZ2_bzCompressInit. The cgo tool discovers these types by invoking the C compiler in a special way on the contents of the comment that precedes the import declaration.

The comment may also contain #cgo directives that specify extra options to the C toolchain. The CFLAGS and LDFLAGS values contribute extra arguments to the compiler and linker commands so that they can locate the bzlib.h header file and the libbz2.a archive library. The example assumes that these are installed beneath /usr on your system. You may need to alter or delete these flags for your installation.

NewWriter makes a call to the C function BZ2_bzCompressInit to initialize the buffers for the stream. The writer type includes another buffer that will be used to drain the decompressor’s output buffer.

The Write method, shown below, feeds the uncompressed data to the compressor, calling the function bz2compress in a loop until all the data has been consumed. Observe that the Go program may access C types like bz_stream, char, and uint, C functions like bz2compress, and even object-like C preprocessor macros such as BZ_RUN, all through the C.x notation. The C.uint type is distinct from Go’s uint type, even if both have the same width.

func (w *writer) Write(data []byte) (int, error) {

if w.stream == nil {

panic("closed")

}

var total int // uncompressed bytes written

for len(data) > 0 {

inlen, outlen := C.uint(len(data)), C.uint(cap(w.outbuf))

C.bz2compress(w.stream, C.BZ_RUN,

(*C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(&data[0])), &inlen,

(*C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(&w.outbuf)), &outlen)

total += int(inlen)

data = data[inlen:]

if _, err := w.w.Write(w.outbuf[:outlen]); err != nil {

return total, err

}

}

return total, nil

}

Each iteration of the loop passes bz2compress the address and length of the remaining portion of data, and the address and capacity of w.outbuf. The two length variables are passed by their addresses, not their values, so that the C function can update them to indicate how much uncompressed data was consumed and how much compressed data was produced. Each chunk of compressed data is then written to the underlying io.Writer.

The Close method has a similar structure to Write, using a loop to flush out any remaining compressed data from the stream’s output buffer.

// Close flushes the compressed data and closes the stream.

// It does not close the underlying io.Writer.

func (w *writer) Close() error {

if w.stream == nil {

panic("closed")

}

defer func() {

C.BZ2_bzCompressEnd(w.stream)

w.stream = nil

}()

for {

inlen, outlen := C.uint(0), C.uint(cap(w.outbuf))

r := C.bz2compress(w.stream, C.BZ_FINISH, nil, &inlen,

(*C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(&w.outbuf)), &outlen)

if _, err := w.w.Write(w.outbuf[:outlen]); err != nil {

return err

}

if r == C.BZ_STREAM_END {

return nil

}

}

}

Upon completion, Close calls C.BZ2_bzCompressEnd to release the stream buffers, using defer to ensure that this happens on all return paths. At this point the w.stream pointer is no longer safe to dereference. To be defensive, we set it to nil, and add explicit nil checks to each method, so that the program panics if the user mistakenly calls a method after Close. Not only is writer not concurrency-safe, but concurrent calls to Close and Write could cause the program to crash in C code. Fixing this is Exercise 13.3.

The program below, bzipper, is a bzip2 compressor command that uses our new package. It behaves like the bzip2 command present on many Unix systems.

gopl.io/ch13/bzipper

// Bzipper reads input, bzip2-compresses it, and writes it out.

package main

import (

"io"

"log"

"os"

"gopl.io/ch13/bzip"

)

func main() {

w := bzip.NewWriter(os.Stdout)

if _, err := io.Copy(w, os.Stdin); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("bzipper: %v\n", err)

}

if err := w.Close(); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("bzipper: close: %v\n", err)

}

}

In the session below, we use bzipper to compress /usr/share/dict/words, the system dictionary, from 938,848 bytes to 335,405 bytes—about a third of its original size—then uncompress it with the system bunzip2 command. The SHA256 hash is the same before and after, giving us confidence that the compressor is working correctly. (If you don’t have sha256sum on your system, use your solution to Exercise 4.2.)

$ go build gopl.io/ch13/bzipper

$ wc -c < /usr/share/dict/words

938848

$ sha256sum < /usr/share/dict/words

126a4ef38493313edc50b86f90dfdaf7c59ec6c948451eac228f2f3a8ab1a6ed -

$ ./bzipper < /usr/share/dict/words | wc -c

335405

$ ./bzipper < /usr/share/dict/words | bunzip2 | sha256sum

126a4ef38493313edc50b86f90dfdaf7c59ec6c948451eac228f2f3a8ab1a6ed -

We’ve demonstrated linking a C library into a Go program. Going in the other direction, it’s also possible to compile a Go program as a static archive that can be linked into a C program or as a shared library that can be dynamically loaded by a C program. We’ve only scratched the surface ofcgo here, and there is much more to say about memory management, pointers, callbacks, signal handling, strings, errno, finalizers, and the relationship between goroutines and operating system threads, much of it very subtle. In particular, the rules for correctly passing pointers from Go to C or vice versa are complex, for reasons similar to those we discussed in Section 13.2, and not yet authoritatively specified. For further reading, start with https://golang.org/cmd/cgo.

Exercise 13.3: Use sync.Mutex to make bzip2.writer safe for concurrent use by multiple goroutines.

Exercise 13.4: Depending on C libraries has its drawbacks. Provide an alternative pure-Go implementation of bzip.NewWriter that uses the os/exec package to run /bin/bzip2 as a subprocess.

13.5 Another Word of Caution

We ended the previous chapter with a warning about the downsides of the reflection interface. That warning applies with even more force to the unsafe package described in this chapter.

High-level languages insulate programs and programmers not only from the arcane specifics of individual computer instruction sets, but from dependence on irrelevancies like where in memory a variable lives, how big a data type is, the details of structure layout, and a host of other implementation details. Because of that insulating layer, it’s possible to write programs that are safe and robust and that will run on any operating system without change.

The unsafe package lets programmers reach through the insulation to use some crucial but otherwise inaccessible feature, or perhaps to achieve higher performance. The cost is usually to portability and safety, so one uses unsafe at one’s peril. Our advice on how and when to useunsafe parallels Knuth’s comments on premature optimization, which we quoted in Section 11.5. Most programmers will never need to use unsafe at all. Nevertheless, there will occasionally be situations where some critical piece of code can be best written using unsafe. If careful study and measurement indicates that unsafe really is the best approach, restrict it to as small a region as possible, so that most of the program is oblivious to its use.

For now, put the last two chapters in the back of your mind. Write some substantial Go programs. Avoid reflect and unsafe; come back to these chapters only if you must.

Meanwhile, happy Go programming. We hope you enjoy writing Go as much as we do.