Digital Archaeology (2014)

1. The Anatomy of a Digital Investigation

This chapter will deal with the structural aspects that are common to most, if not all, digital investigations. Most current texts on the subject refer to a common investigation model, although there is some disagreement on how many components make up the model. This book will use a six-part model, which will be covered in more detail later in this chapter.

It is essential to understand at the outset precisely what the scope of the investigation entails. The type of investigation dictates the level of authorization required. Generally, there are three types of investigation. Internal investigations are sponsored by an organization. They generally start out as a deep, dark secret that the company doesn’t want getting out. Therefore, courts and state and federal agencies are rarely involved at the outset. The other two types—civil and criminal—both require involvement by the courts, but on different levels.

There will never be an investigation that does not have multiple stakeholders. In all court cases, there is the plaintiff and the defendant. In civil cases, these are the two litigants asking the courts to settle a dispute. In criminal cases, the defendant is the person accused of a crime and the plaintiff is the one making the accusation, which will always be some level of government authority. In addition to these obvious players, there are those on the sidelines whose interests must be considered. Lawyers will almost always be involved, and in cases that are likely to end up in court, be assured that the judge will take an active interest.

With people’s finances, freedom, or even lives at stake, the necessity for accurate and thorough reporting cannot be emphasized enough. It is so critically important that the subject of documentation will be discussed several times and in several places in this book. This chapter will start the reader off with the basics of good documentation.

Please be aware that this chapter deals only with the process of investigation. In Chapters 2 and 3, there will be detailed discussions of the various legal issues that the digital investigator must face on a daily basis. Consider the legal issues to be the glue that binds the model, but not the actual model. You can perform any number of investigations with no regard for the law. The results will be very revealing, but useless. Failure to be aware of legal aspects will cause the most perfectly executed investigation to fall apart the instant the case is picked up by the legal team.

A Basic Model for Investigators

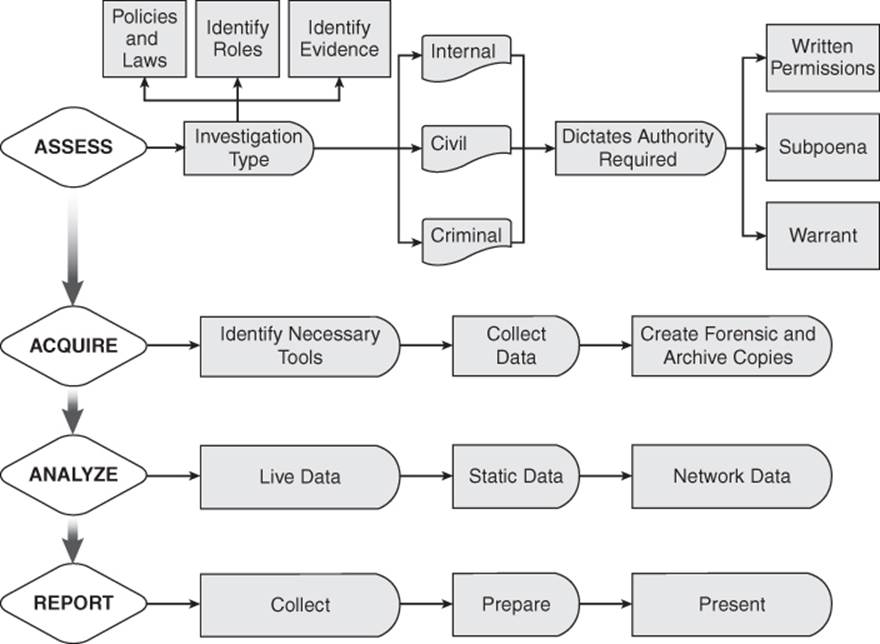

Today’s teaching methods require everything to be broken down into a simplified structure that you can put into a diagram. Computer investigations are no different. Even though there will probably never be any two cases that are identical, they should always be processed in accordance with a standard investigative model. Kruse and Heiser (2001) laid out the basic computer investigation model in their book entitled Computer Forensics: Incident Response Essentials. Their model was a four-part model with the following steps:

• Assess

• Acquire

• Analyze

• Report

As shown in Figure 1.1, the four steps are further broken down into more granular levels that represent processes that occur within each step. A more thorough study expands the model to six steps, as follows:

• Identification/assessment

• Collection/acquisition

• Preservation

• Examination

• Analysis

• Reporting

Figure 1.1 The steps of a digital investigation

The six-step model (Casey 2001) as seen in Figure 1.1 emphasizes the importance (and process) of preserving the data. It also distinguishes between the process of examination and analysis, whereas Kruse and Heiser considered them to be two parts of a single process. Experience has shown that acquisition and preservation are not the same, and while it might be an easy enough procedure to extract and examine data, accurate analysis is as much an art as it is a science.

From a management standpoint, each of these steps must be carefully monitored. Through a process of careful documentation of the history of each case, the various processes can be constantly reassessed for efficiency and reliability. When it becomes necessary, knowing what works and what doesn’t allows the observant manager to tweak the steps in order to improve organizational effectiveness.

Figure 1.1 emphasizes just how detailed these seemingly simple steps can actually be. The assessment phase alone has a multitude of steps involving people, hardware, environment factors, political implications, and jurisdiction. Acquisition of evidence cannot begin until all potential sources of evidentiary material are identified, collected, inventoried, and catalogued. All of this must be done according to strict legal guidelines, or any subsequent investigation will be a waste of time. Legal and internal regulations regarding privacy must be followed at all times, or any information collected will not be admissible as evidence should the case ever make its way to court. In the case of internal investigations, adherence to corporate guidelines will generally be sufficient.

Identification/Assessment

Before beginning any investigation, the general rules of engagement must be established in advance and from the very start be strictly followed. Those rules can be very different between criminal and civil cases. It is essential that the investigator know what regulations apply to a specific investigation in order to not damage or destroy a case by failure to abide, either flagrantly or inadvertently.

In a criminal investigation, it is almost always necessary to obtain a warrant before seizing systems, media, or storage devices. In order to obtain that warrant, the investigating entity must provide a judge sufficient evidence that a crime has been committed, is about to be committed, or is in the process of commission. The specific type of information sought by the investigation must be identified; general fishing expeditions are never approved by a reputable judge—at least not for the purpose of issuing warrants.

Civil cases have more lenient guidelines. Internal investigations sponsored by an organization can be even more lenient. Federal guidelines regarding invasion of privacy are not as strictly enforced on civilian investigators looking into civil infractions as they are on agents of a government—state, federal, or local—who are investigating criminal complaints. Internal investigations can be made even easier when employees or members have signed a statement outlining an organization’s policies and guidelines.

No case should be accepted by an investigator directly. An executive-level decision, based on a set of predefined guidelines (to be discussed later), must be made on whether to accept or decline each individual case presented to the organization. While it falls upon a law enforcement agency to accept any case assigned that involves violation of state or federal statutes, a private organization can refuse to accept cases for a variety of reasons. The organization’s leadership must indentify the criteria for case acceptance and stick to those criteria. It does the company’s reputation no good to be associated with a pedophile after publicly stating that its motives are to defend the community.

Make a list of all legal documentation that will be required. Warrants will be required in criminal cases. Court orders or subpoenas will be needed in civil matters. Signed agreements outlining the scope of the investigation should be required in all internal investigations.

Once the ground rules are established, it is time to identify potential sources of evidence. The obvious place to look is on the local system, including hard disk drives, removable media that might be lying about, printers, digital cameras, and so forth. Less obvious sources of information might be PDAs, external hard disks or optical drives, and even system RAM if the data processing systems are still running when the incident is reported. Knowing in advance what must be acquired can prevent the investigator from making critical errors during the process of acquisition.

Collection/Acquisition

This is the most technical part of the investigation and can also be the most critical time for making errors. If the case under scrutiny should ever come to trial, the investigator presenting the case must be able to prove the following:

• The data is authentic.

• The copy of the data used for analysis is reliable.

• The data was not modified during acquisition or analysis (chain of custody).

• The tools used to analyze the data are valid tools.

• Sufficient evidence, both incriminating and exculpatory, has been acquired and analyzed to support the proffered conclusion.

• The conclusions drawn are consistent with the data collected and analyzed.

• People involved in the collection and analysis of the data are properly trained and qualified to do their job.

This doesn’t sound easy, and it isn’t. Details on how to assure that all of these requirements are met are covered in greater detail in later chapters. For now, suffice it to say that it is essential that they be fulfilled.

Preservation

A cardinal rule of digital investigation is that the original data must never be touched. For many years, the standard rule has been that a forensically sound copy of the original be made and that the examination and analysis of data be performed on the forensic copy. In terms of nonvolatile media, such as hard disks, removable media, and optical disks, this is still the rule. Devices should always be mounted as read-only in order to assure that no data is modified or overwritten during the process of mounting the device. Hard disk duplicators are designed specifically for this purpose, and in Windows systems, a simple modification of the registry allows USB devices to mount read-only.

Legal issues might arise if there is any possibility that media used to store images may have been contaminated. Be aware of that possibility and either have new media available for collection or be certain that previously used media has been forensically wiped.

In many cases, it becomes essential that copies of data be acquired through a process of live acquisition. This is the case when it becomes necessary to capture the contents of memory from a running system, to acquire log files from network devices that cannot be brought down, or to archive information from network servers or storage appliances that defy the making of a forensic copy. If it is not possible, for any reason, to create a forensically sound copy, it is essential that the investigator document the reasons such a copy could not be made and record as accurately as possible the state of the evidentiary source before and after acquisition.

Storage of preserved information becomes part of the chain of custody process, and care must be taken that all data and devices collected during this phase are properly documented and tracked. Be able to verify that there was never a possibility for evidence to become tainted through outside tampering, corruption, or improper procedure.

Examination

The process of examining data increases in scope and complexity every year. Whereas 1.44MB floppy disks were once the repository for stolen and illicit data, investigators these days are presented with flash drives the size of key fobs that hold 64 or more gigabytes of data and hard disks that store in excess of a terabyte. To make matters worse, the data is not likely to sit on a porch swing in plain view for anyone to see. Investigators will find it necessary to look for evidence in unallocated space left behind by deleted files. Hidden partitions, slack space, and even registry entries are capable of hiding large quantities of data. Steganography can hide documents inside of an image or music file. So essentially, the investigator is given an archive the size of the Chicago Public Library and asked to find a handwritten note on the back of a napkin tucked somewhere inside of a book.

Data carving tools and methods of looking for evidentiary material have evolved, and depending on the nature of the case, the investigator’s tool kit will require having several utilities. For criminal cases requiring forensically sound presentation, it is critical that the tools used to examine data be those considered valid by the courts. There are a few commercially available software suites approved for evidentiary use. Among these are Encase by Guidance Software and the Forensics Tool Kit (FTK) from Access Data Corporation. A suite of tools running on Linux that is not “officially” sanctioned but is generally considered acceptable by most courts is The Sleuth Kit, designed by Brian Carrier.

Keeping up with technical innovations in the industry is most critical in this area. As new technology emerges, new tools will be needed to examine the accumulated data it creates. The organization that follows the cutting edge of technology will always be two steps behind those that help develop it. The balancing act comes when management must defend the use of a new tool to which the courts and lawyers have not yet been exposed. Be prepared to defend the tool along with the conclusions it helped you formulate.

Analysis

Here is where the process of digital forensic investigation leaves the realm of technology and enters that of black magic. It is up to the investigator to determine what constitutes evidence and what constitutes digital clutter. A variety of tools exist that assist the investigator in separating OS files from user data files. Others assist in identifying and locating specific types of files.

Technique is as critical as the selection of tools. For example, when searching an e-mail archive for messages related to a specific case, string searches can bring up all those that contain specific keywords. Other utilities can detect steganography or alternate data streams in NTFS file systems. Collecting the data necessary to prove a case becomes as much art as it is science. One thing that the investigator must always keep in mind is that exculpatory evidence must be considered as strongly as incriminating evidence.

Reporting

Documentation of the project begins the minute an investigator is approached with a potential case. Every step of the process must be thoroughly documented to include what people are involved (who reported what, who might be potential suspects, potential witnesses, or possible sources of help), as well as thorough documentation of the scene, including photographs of the environment and anything that might be showing on computer monitors. Each step taken by the investigator needs to be recorded, defining what was done, why it was done, how it was done, and what results were obtained. Hash files of data sources must be generated before and after acquisition. Any differences must be documented and explained. Conclusions drawn by the investigating team must be fully explained. On the witness stand, it is likely that an investigator will be required to prove his or her qualifications to act as an investigator. A meticulously investigated case can be destroyed by inadequate documentation. While commercial forensic suites automate much of the documentation process, there is still much manual attention required of the investigator.

Understanding the Scope of the Investigation

As mentioned, there are three basic types of investigation. With each type, the rules get tighter and the consequences of failure to comply get progressively stricter. A good rule of thumb is to pretend that the strictest rules apply to all investigations. However, as you might imagine, there are some role-specific requirements that don’t apply to all of them.

Internal Investigations

Internal investigation is the least restrictive of the inquiries you might make. From a standpoint of professional courtesy, internal investigations are more likely to be the least hostile type you’ll ever do. You work directly with management, and the target of your inquiries probably won’t even be aware of your activities until you are finished. You don’t have courts and lawyers combing every word you say or write, hoping to find the smallest mistake.

That is not to say that there aren’t laws that apply to internal probes. There most certainly are. State and federal laws regarding privacy apply to even the smallest organization. Also, different states have different laws regarding how companies deal with employment matters, implied privacy issues, and implied contracts. This isn’t intended to be a law book, so for the purposes of brevity and clarity, understand this. It is important to review any relevant regulations before you make your first move.

Most corporations have formal guidelines for such matters. In addition to a written employee handbook, it is very likely that a company has documented guidelines regarding issues leading to termination, use of company infrastructure (including computers, e-mail systems, and network services), and so forth. In every step of your process, make sure that you adhere to the law and to corporate policy. If there appears to be a conflict between the two, get legal advice. At the very least, make sure you have written authorization to perform every step you take. Management needs to be aware of your process and every step involved in the course of investigation, and they must sign off, giving approval. Document everything you do, how you did it, and what results you obtained. In digging into the source and impact of any internal security breach, your foremost concern is the protection of your client. However, should your probe uncover deeper issues, such as illegal activity or a national security breach, then it becomes necessary to call in outside authorities.

Civil Investigations

Civil cases are likely to be brought to the organization in situations where intellectual property rights are at risk, when a company’s network security has been breached, or when a company suspects that an employee or an outsider is making unauthorized use of the network. Marcella and Menendez (2008) identify the following possible attacks:

• Intrusions

• Denial-of-service attacks

• Malicious code

• Malicious communication

• Misuse of resources

An investigator involved in a civil dispute should be cognizant of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Although a legal degree is hardly necessary, a strong background in civil law is invaluable. Additionally, experience in business management is useful, in that a good understanding of standard corporate policy is necessary. Good communications skills are required. Management needs to be able to feel equally comfortable dealing with a CEO or a secretary.

When working with large repositories of data connected to many different users and devices, it becomes more difficult to assess who actually committed an infraction. Proving that a specific user was accessing the network at a specific time (and possibly from a particular machine) can be critical to winning a case. Anson and Bunting (2007) point out the difficulties of generating an accurate timeline and recommend some good tools for simplifying the matter. A good manager will keep abreast of changing technology and make sure that the organization is equipped with the proper tools.

Tools required for examining large networks or performing live data capture are substantially more expensive than those used to search individual data sources. Generally, it is not possible to bring down a corporate network while the investigative team captures images of thousands of drives. Costs in time and materials would be prohibitive, as would be the negative impact of downtime on the company. Specialized software is needed to capture, preserve, and document the data. Additional tools are needed for data reduction. Filtering out the general network chatter and unrelated business documents can be a time-consuming process.

Keeping up with newer technology is essential, as is constant refresher training. The organization must continually assess its current capabilities and apply them to what imminent future needs are likely to be. As technology advances, investigative tools and techniques need to advance as well. Cases are won and lost on the ability of investigators to extract evidence. If a forensics team finds itself faced with a technology it doesn’t understand, there will be no time for on-the-job training.

Criminal Procedure Management

Defining precisely what constitutes computer crime is very difficult to do. Fortunately, it is not up to the investigator to determine what is and what is not criminal activity. However, some definitions have been presented by various experts. Reyes (2007) states that a computer crime will exhibit one or more of the following characteristics:

• The computer is the object, or the data in the computer are the objects, of the act.

• The computer creates a unique environment or unique form of assets.

• The computer is the instrument or the tool of the act.

• The computer represents a symbol used for intimidation or deception.

Generally speaking, computer crimes are little different from conventional crimes. Somebody stole something, somebody hurt somebody else, somebody committed fraud, or somebody possessed or distributed something that is illegal to own (contraband). While not an exhaustive list of possible computer crimes, the following is a list of the most commonly investigated:

• Auction or online retail fraud

• Child pornography

• Child endangerment

• Counterfeiting

• Cyberstalking

• Forgery

• Gambling

• Identity theft

• Piracy (software, literature, and music)

• Prostitution

• Securities fraud

• Theft of services

Prosecution of criminal cases requires a somewhat different approach than do civil cases. Legal restrictions are stricter, and the investigator is more likely to be impacted by constitutional limitations regarding search and seizure or privacy. Failure to abide by all applicable regulations will almost certainly result in having all collected evidence suppressed because of technicalities. Many civil investigations are not impacted as severely by constitutional law because there is no representative of the government involved in the investigation. To assure that the investigation succeeds, management of a criminal division needs to have someone with a strong legal background. Courts will use the Federal Rules of Evidence to decide whether or not to allow evidence to be admitted in an individual case.

For the same reasons, reporting procedures and chain of custody must be rigorously followed by each person involved in an investigation, whether they are involved directly or peripherally. Even a minor departure from best practice is likely to be challenged by opposing counsel. Because of this, selection of personnel becomes a greater challenge. A technical whiz with little or no documentation ability is likely to fail in criminal investigation. Anyone who demonstrates a disregard for authority is a poor candidate for investigating criminal cases.

Tools used in criminal cases are subject to a tighter scrutiny than those used in civil cases. When a person’s life or liberty hangs in the balance, judges and juries are less sympathetic to a technician who cannot verify that the tools used to extract the evidence being presented are reliable. Software and hardware tools used by the organization must be recognized by the court for use, and the techniques used by investigators must be diligently documented to show there was no deviation from accepted standard procedures.

Funding is likely to be more limited in criminal work than in civil investigations. Money will be coming from budget-strapped government entities or from law offices watching every dime. In some cases, courts will apply the Zubulake test to determine if costs should be shifted from one party to the other. This test is based on findings from the case Zubulake v. UBS Warburg (217 F.R.D. at 320, 2003) where the judge issued a list of seven factors to be considered in ordering discovery (and in reassigning costs). These factors are to be considered in order of importance, the most important being listed first:

1. The extent to which the request is specifically tailored to discover relevant information

2. The availability of such information from other sources

3. The total cost of production compared to the amount in controversy

4. The total cost of production compared to the resources available to each party

5. The relative ability of each party to control costs and its incentive to do so

6. The importance of the issues at stake in the litigation

7. The relative benefits to the parties of obtaining the information

Identifying the Stakeholders

In any investigation, there are going to be a large number of people with a vested interest in the outcome. These people are the stakeholders. Stakeholders vary in each investigation, depending in part on the scope of the investigation and in part on the raw size of the organization and the data set involved. Sometimes it is easy for the investigator to become overwhelmed by the sheer number of people involved. In all cases, it is safe to assume that there are two primary stakeholders with a greater investment than any other. Those are the accused and the accuser.

The accuser is the easiest to identify. This is the person or the organization that initiated the inquiry to begin with. As simple as that may seem, all too often the actual accuser gets left in the wake of bureaucracy and procedure. This is particularly true in cases that are destined to be presented before a court. Lawyers suddenly take the place of the stakeholders, and the assumption becomes that suddenly they are the primary stakeholders. A good investigator never lets this happen. Communications may be with these attorneys as representatives of the stakeholders, but the primary stakeholders remain the accused and the accuser.

Depending on the magnitude and the scope of the case, there might be a wide variety of secondary stakeholders—or none at all. To be a stakeholder of any kind, an individual or organization must have something to gain or lose from the outcome of the investigation. In spite of possible arguments to the contrary, this does not include the news media. Key stakeholders include

• Decision makers: Those who have the authority to initiate or to cancel an investigation or to reassign personnel.

• Mediators: Judges or third-party arbitrators who are responsible for deciding the outcome of the case or issue decisions pertaining to procedure.

• Customers: People or organizations downstream from the accused or accuser who will be directly impacted by the decision. For example, in i4i Limited Partnership v. Microsoft Corporation, virtually every reseller of Microsoft Word was impacted (i4i v. Microsoft Corporation,6:07VC113, 2009).

• Process owners: People or organizations whose actions may have contributed to the case or whose operations were or will be impacted by the case.

Extraordinary circumstances can lead to unexpected stakeholders. The Exxon-Valdez incident in 1989 started out as the accidental grounding of an oil tanker that resulted in Exxon’s launch of an investigation into the actions of the ship’s captain. Before it was over, there were more than 38,000 litigants, including individuals, agencies, and environmental organizations, and three different sets of judges involved in a variety of decisions (Lebedoff 1997). That’s a lot of stakeholders.

The Art of Documentation

Any individual who lacks organizational skills or who finds it difficult to keep accurate notes as he works is not a likely candidate for the position of digital investigator. The vast majority of work the investigator does is documentation. There are five levels of documentation that must be either maintained or created during the course of each case study:

• General case documentation

• Procedural documentation

• Process documentation

• Case timeline

• Evidence chain of custody

Every one of these is important to winning a case should it make its way to court. Faulty, incomplete, or missing documentation can destroy an otherwise meticulously prepared case. In addition to these items, there is also the final report, but that will be covered elsewhere in this book.

The Craft of Project Management

While this book is not intended to be a treatise on what makes a good project manager, it should be pointed out that good project management practices can facilitate the smooth completion of an investigation from beginning to end. Virtually all of the principles defined in the Project Management Institute’s (PMI) Project Management Book of Knowledge (PMBOK) apply directly to the investigatory process. Wysocki (2009) defines a project as “a sequence of unique, complex, and connected activities that have one goal or purpose and that must be completed by a specific time, within budget, and according to specification.”

Like all other projects, a digital forensics investigation involves multiple stakeholders and a defined scope, and has specific objectives that must be pursued. Multiple people will be involved, requiring the project leader to manage people’s time, to assure that tasks are assigned to the person most skilling in performing the work involved, and to keep everything in budget and on time.

General Case Documentation

Case documentation begins the moment you are asked to consider investigating an incident. Even if an investigator or agency chooses not to accept a case (assuming that possibility exists), it may later become necessary to explain why the case was turned away. Another thing the investigator needs to keep in mind is that anything recorded during the case is discoverable. To be discoverable means that opposing counsel has the right to examine and analyze data collected during the process. If an investigator takes written notes or uses a digital voice recorder to make verbal observations, copies of the notes and audio files must be made available to the opposition if requested. Therefore, great care should be taken in the creation of documentation.

A number of factors need to be addressed in the basic case documentation:

• What is the name and contact information for the organization involved in the incident? Record every individual contacted during the investigation, that person’s role in the process, and when, where, and how he or she was contacted.

• When was the investigative agency notified, and who initially took the information? Record exact dates and times.

• A description of the incident, both in technical terms and in lay terms.

• When was the incident discovered?

• When did the incident occur? This may be a best-guess scenario.

• Who discovered the incident?

• To whom was the incident reported? This means anyone who learned of it, regardless of rank and file.

• What systems, information, or resources were impacted by the event? This includes hardware, organizational entities, and people.

• Is there any preliminary information that suggests how the offending actions were accomplished?

• What is the impact of the incident on the individual or organization affected? This includes financial impact, impact on the systems involved, and any effect it may have had on the health or mental welfare of individuals involved.

• What actions were taken between discovery of the incident and reporting it to authorities? This means everything that was done, including simple files searches.

• Who are the stakeholders as they are identified?

• As soon as possible, provide a detailed inventory of all hardware (and possibly software) that is involved in the incident. If hardware is seized, provide a separate, itemized list of seized equipment.

• Have all copies of all pertinent documentation, such as warrants, summons, written correspondence, and so forth, been added to the case file?

Any other generic information that does not fit directly into one of the other reporting categories would be included in this section. This would include expense reports, timesheets, and any other general recordkeeping.

Procedural Documentation

During the course of the investigation, a number of tasks will be performed. The history of these tasks should be maintained as painstakingly as possible. The investigator should describe every step taken, the tools used to perform specific tasks, a description of the procedure, and a brief summary of the results. Detailed results can be included in the final report. When describing a technical process, process documentation should be provided whenever possible (as described in the next section).

Anytime the investigator chooses not to follow recommended best practice, it is essential to record the action being taken, what the recommended procedure would normally be, and what actual procedure is being used, and to explain precisely why the deviation is occurring. For the longest time, the best practice when coming upon a running suspect system was to pull the plug. The reasoning was that an orderly shutdown of the system overwrote a lot of data and drastically altered paging files. However, in a live network event that is still transpiring, it may be necessary to collect information from active memory, including current network connections, user connections, and possibly cached passwords. Shutting down the system would kill all that information. The proper course would then be to perform a live analysis and document precisely why the action was taken.

The following is a summary of events and tasks that should be meticulously reported. Some organizations performing investigations on a full-time basis have a template that the investigator follows, filling in the results as tasks are completed.

• Document the condition of the original scene, including a list of hardware found, status (on/off, logged on/logged off, etc.), along with photographs or a video tape.

• Record the names and contact information of all individuals interviewed during the investigations. A summary (or if possible, a transcript) of the interview should be provided as an attachment.

• If equipment is seized, document the make, model, and serial numbers of each device. Provide documentation authorizing the seizure as a separate attachment.

• Record the exact time materials were seized, the location it was taken from, and the name and contact information of the person performing the action.

• If equipment is transported, provide a detailed description of how the devices were packaged if antistatic or Faraday protection was provided. If not, why not?

• Describe the location where seized materials were taken, including the location and type of storage facilities used to house the materials. Record the name and contact information of the person transporting each item.

• Whenever live data acquisition is deemed necessary, record the following:

• What type of date was acquired (memory dump, system files, paging files, etc.)?

• What tools and procedures were used to connect to the suspect machine?

• What tools and procedures were used to acquire the data?

• What was the time and date the data was imaged, and what was the time and date reported by the device from which the data was acquired? The two are not always the same.

• What are the type, make, model, and serial number of the target device to which the data was copied?

• What is the condition of the target device (new, forensically cleaned, data-wiped, or formatted)?

• What are the MD5 and SHA-2 hash calculations of the image?

• When devices are imaged for later analysis, record the following:

• The type, make, model, and serial numbers of source devices

• The type, make, model, and serial numbers of target devices

• Precautions taken to avoid contamination or loss of data in evidence

• For disk drives:

![]() Drive parameters of disk drives, both target and source

Drive parameters of disk drives, both target and source

![]() Jumper settings

Jumper settings

![]() Master/slave configuration if IDE

Master/slave configuration if IDE

![]() Device ID if SCSI or SATA

Device ID if SCSI or SATA

• For optical or flash drives:

![]() Make, model, and capacity

Make, model, and capacity

![]() Mounted or not mounted at time of seizure

Mounted or not mounted at time of seizure

![]() Inventory of blank or used media

Inventory of blank or used media

• For seized media:

![]() Form of disks (CD, DVD, Zip, etc.)

Form of disks (CD, DVD, Zip, etc.)

![]() Capacity of disks

Capacity of disks

![]() Number and type of seized disks

Number and type of seized disks

![]() Possible evidence that there are missing disks (empty jewel boxes, etc.)

Possible evidence that there are missing disks (empty jewel boxes, etc.)

• The date and time of each action taken.

• The process used for mounting the seized device, including mechanisms in place to assure write-protection

• The process and tools used to acquire the forensic image

• MD5 and SHA-2 hash calculations of the image before and after acquisition

• Photograph computer systems before and after disassembling for transport.

• During the examination and analysis of data, record each procedure in detail, identifying any tool used. Record beginning and ending hash calculations of source data, explaining any discrepancies that may occur.

• Above all: Maintain an unbroken chain of custody that includes each piece of evidence handled throughout the course of the investigation.

As is readily apparent, case documentation is not to be taken lightly. While individuals should be treated as innocent until proven guilty, sources of evidence by default get the opposite treatment. The astute investigator always assumes that any case he or she is working will eventually end up in court. Even the seemingly benign cases, such as uncovering evidence of employee misconduct, can end up in court as a civil (or even criminal) court case. Poor documentation can endanger what would otherwise be a sound case.

Process Documentation

Unless an investigator or an organization utilizes homegrown tools, most process documentation is likely to come from the vendors providing the hardware or software used. There are some pieces of documentation that must be generated by the agency. Process documentation includes

• User manuals

• Installation manuals

• Readme files stored on installation media

• Updates to manuals posted online by the vendor

• Logs showing updates, upgrades, or patch installations

This is the type of documentation that does not necessarily need to be provided with each investigation report. It must, however, be available if demanded by opposing counsel, a judge, or arbitrator. There are situations that occur where process documentation is used to support or refute claims that proper procedure was followed during specific steps in the investigation.

Building the Timeline

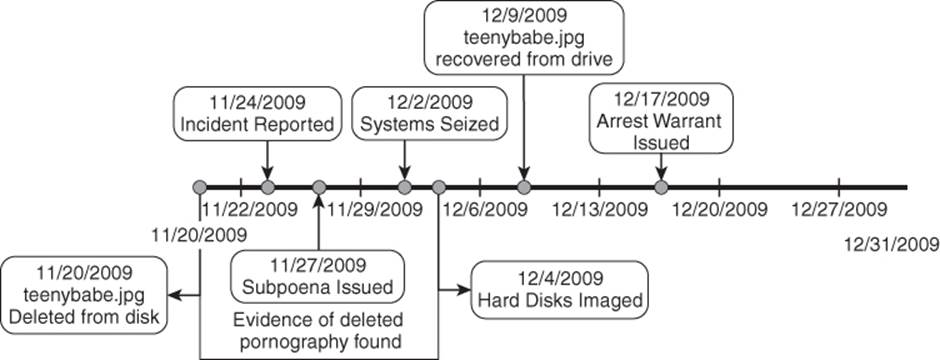

Key to virtually every investigation involving computer or network activity is the creation of an accurate history of events related to the incident under investigation. By creating an easily comprehensible report of the order of events that occurred, the investigator can more easily and more accurately show correlation between those events. For example, it is easier to associate a specific user to the origination of a particular file if the timeline shows that the file was created at a time when it can be shown unequivocally that the user was logged onto the computer or network.

The timeline (Figure 1.2) needs to start from a time just before the incident was known to begin or was initially discovered to the point when the evidentiary materials were acquired for analysis. This is why it is essential that the investigator do nothing that could alter the metadata of files stored on the computer. Metadata is information about files that can be either stored within the file itself or extracted from other repositories, such as the Windows master file tables or registry. Three critical pieces of information are the creation date, last accessed date, and last modified date. Together these form the file’s MAC (modified, accessed, and created) data. Simply viewing a file in a browser or application alters the accessed data. Copying a file from one location to another can modify both the creation and modified dates if forensically acceptable methods are not used. Metadata and ways of protecting and analyzing it will be covered in greater detail in Chapters 9 and 10.

Figure 1.2 A good timeline is essential in communicating the order of events to outside parties of interest.

Network and user logon activity are also critical to creating a timeline, as are Internet and e-mail usage. There are various tools that help the investigator validate times that certain events occurred. MACtime is a common forensic tool that can extract a history of user activity on a system. It creates an ASCII timeline of file activity. X-Ways Trace can be used to extract and analyze Internet history. In a network environment, event tracking in utilities such as Microsoft’s Event Viewer, the registry, or log files can reveal valuable information that can be used for assembling a credible timeline.

Timelines can be assembled in graphical form that makes it easy for laypeople such as lawyers and judges to understand. Some of the forensic suites (notably Encase) produce automated timelines. Others, such as the Forensic Tool Kit, do not. It is possible, but not necessarily pleasant, to create a timeline using commercial products such as Microsoft Visio, Excel, or OpenOffice. Excel is very cumbersome for this task and is not recommended. Microsoft Visio produces more polished timelines but is limited by the fact that each event must be entered into the timeline separately. A better use of the investigator’s time is to invest in a proprietary product such as Timeline Maker for Windows or Bee Docs for Macintosh computers.

Chain of Custody Reports

For every physical unit of evidence taken into possession by an investigator or agency, there must be a continuously maintained chain of custody report. Consider it the equivalent of a timeline for evidence. The chain of custody report must be able to verify several critical pieces of information:

• Identify the item precisely, listing type of evidence, make, model, and serial number (if relevant), and make a photograph of the item (if possible).

• Specify when was the item taken into possession.

• Identify where or from whom the item was seized.

• Record who acquired the item along with the time and date acquired.

• Document who transported the item and how was it transported.

• Document how was the item stored during transport.

• Regularly record how the item was stored during possession.

• Provide a continual log, showing the time and date of each time it was checked out for examination, the purpose for checking it out, and the time and date it was checked back in for storage, identifying who had possession of the item during that time.

While an item is in possession of an individual investigator, that person should document what steps were taken to preserve the integrity of the evidence while in possession. Such documentation needs to include a precise identification of the device in possession (as defined above) and what controls were in place to protect the device from electrostatic discharge, electromagnetic interference, and other potential sources of data corruption and other protections. Document what methods were used to prevent data from being inadvertently written to the device (write-blocker devices, software write-protection, etc.). Generate before and after hash values to confirm that the data source did not change while in possession. If it did change, document what process caused the change, along with how and why the change occurred.

Any deviation from standard documentation procedures in preparing the chain of custody can, and most likely will, lead to challenges from opposing counsel and can possibly cause the evidence to be thrown out. No breaks can exist in the timeline, because this indicates an opportunity for the data to be replaced, corrupted, or modified.

Case Law: Chain of Custody

It is inevitably a good idea to present a flawless chain of custody in order to avoid having evidence declared inadmissible. The courts have vacillated in how they treat evidence in regards to “missing links” in the chain. In Jeter v. Commonwealth, Justice Roberts of the Twelfth Virginia Appellate Court wrote, “When a ‘vital link’ in the possession and treatment of the evidence is left to conjecture, the chain of custody is incomplete, and the evidence is inadmissible” (Jeter v. Commonwealth 2005).

Conversely, in Hargrove v. Commonwealth, the defendant argued that since the chain of custody did not include any signed statements or testimony from the officer who delivered the evidence to the laboratory, nor was there any evidence that an authorized agent accepted delivery of the evidence at the lab, the integrity of the evidence was in doubt. In denying this appeal, Justice Felton wrote, “It concluded that because the evidence container was received at the lab ‘sealed and intact,’ there was no evidence that it was subject to tampering between the time it left the police evidence room and the time that it was removed from the lab storage locker. We conclude that the trial court did not err in admitting the evidence container and the certificate of its analysis” (Hargrove v. Commonwealth 2009).

Chapter Review

1. In what ways does Casey’s six-step model differ from the earlier four-step models of digital investigation? What is new, and what has changed?

2. Where in the Casey model would one begin to ascertain precisely what legal documentation would be required for a particular investigation?

3. Is Zubulake v. UBS Warburg more relevant to a criminal case or a civil matter? Explain your answer.

4. Discuss the difference between procedural documentation and process documentation. In which document would you explain what steps you took during the examination of a file system?

5. During the process of examination, you have reason to suspect that files that were deleted may still exist. What is the process for locating intact files in unallocated disk space?

Chapter Exercises

1. Look up at least one criminal case that involved data carving. Was the technique useful for the prosecution or for the defense?

2. Think of as many ways as possible in which a civil case involving electronic discovery of specific e-mails would differ from a criminal cases in which a search of a suspect’s e-mail archives must be conducted. Don’t try to get too specific here, as this is simply an overview chapter.

3. Throughout the investigation, a myriad of actions are performed. At what point does the chain of custody begin, and how is it relevant at each subsequent stage?

References

Anson, S., and S. Bunting. 2007. Mastering Windows network forensics and investigation. Boca Raton: Sybex.

Casey, E. 2004. Digital evidence and computer crime. New York: Elsevier Academic Press.

Hargrove v. Commonwealth. 2009. Record No. 2410-07-2. Court of Appeals of Virginia Published Opinions. www.courts.state.va.us/wpcap.htm (accessed April 8, 2010).

Hargrove v. Commonwealth, 44 Va. App. 733, 607 S.E.2d 734 (2009). www.lexisone.com/lx1/caselaw/freecaselaw?action=OCLGetCaseDetail&format=FULL&sourceID=bdjcca&searchTerm=eGjb.diCa.aadj.eeWH&searchFlag=y&l1loc=FCLOW (accessed April 8, 2010).

Jeter v. Commonwealth, 44 Va. App. 733, 737, 607 S.E.2d 734 (2005).

Kruse, W., and J. Heiser. 2001. Computer forensics: Incident response essentials. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Lebedoff, D. 1997. Cleaning up: The Exxon Valdez case—The story behind the biggest legal bonanza of our time. New York: Free Press.

Marcella, A., Jr., and D. Menendez. 2008. Cyber forensics: A field manual for collecting, examining, and preserving evidence of computer crimes, 2nd ed. Florida: Auerbach Publications.

Reyes, A. 2007. Cyber crime investigations. Rockland: Syngress Publishing

Wysocki, R. 2009. Effective project management: Traditional, agile, extreme. 5th ed. Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons.

Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, 217 F.R.D. at 320 (2003).