Fire in the Valley (2014)

Chapter 7

Apple

I try to get people to see what I see. When you run a company, you have to get people to buy into your dreams.

Steve Jobs

It was the prototypical Silicon Valley start-up story: two smart boys with a driving passion and an angel investor, all three of them willing to risk it all for a chance at the gold ring. Conceived at a Homebrew meeting and launched on April Fool’s Day, Apple would grow to be the most valuable company in the world. But it started with two bored teenagers playing with scavenged electronics.

Jobs and Woz

Woz was fortunate to hook up with an evangelist.

—Regis McKenna, high-tech marketing guru

There were still orchards in Santa Clara Valley.

But by the 1960s it was no longer the largest fruit-producing area in the world. It was starting to transition to urban sprawl as the electronics and semiconductor companies began taking over, and for the son of an engineer in Sunnyvale it was easier to pick up a spare transistor than to find somewhere to pick an apple.

The Prankster

In 1962, an eighth-grade boy in Sunnyvale built an addition-subtraction machine out of a few transistors and some parts. He did all the work himself, soldering wires in the backyard of his suburban home in the heart of what became Silicon Valley. And when he entered the machine in a local science fair, no one who knew him was surprised that he won the top award for electronics. He had designed a tic-tac-toe machine two years earlier and, with a little help from his engineer dad, had assembled a crystal radio in the second grade.

The boy, born Stephen Gary Wozniak, but called Woz by his friends, was brilliant, and when a problem caught his interest, he worked relentlessly to solve it. When he enrolled in Homestead High School in 1964, Woz quickly became one of the top math students there, although electronics remained his true passion. Unfortunately for the teachers and administrators of Homestead High, that wasn’t his only passion.

Woz was a prankster, and he applied the same ingenuity and determination to carrying out his practical jokes as he did to building electronics. He spent hours at school concocting the perfect prank. His jokes were clever and well executed, and he usually emerged from them unscathed.

But not always. Once, Woz got the bright idea to wire up an electronic metronome and plant it inside a friend’s locker, its bomblike ticking audible to anyone standing nearby. “Just the ticking would have sufficed,” Woz said, “but I taped together some battery cylinders with the labeling removed. I also had a switch that sped up the ticking when the locker was opened.” But it was the high-school principal who fell for the trick. Bravely snatching the “bomb” from the locker, he ran out of the building with it. Wozniak thought the whole incident was hilarious. Post-9/11 he would probably have been expelled. At the time, the principal showed his appreciation of the joke by suspending Woz for two days.

The Cream Soda Computer

Soon after that, Steve Wozniak’s electronics teacher, John McCullum, decided to take him in tow. Woz clearly found high school less than stimulating, and McCullum saw that his pupil needed a genuine challenge. Although Woz loved electronics, the class McCullum taught was nowhere near demanding enough. McCullum worked out an arrangement with Sylvania Electronics whereby Wozniak could visit the company’s nearby facilities during school hours to use their computers.

Woz was enthralled. For the first time, he saw the capabilities of a real computer. One of the machines he played with was a Digital Equipment Corporation PDP-8 minicomputer. “Play” for Woz was an intense and engrossing activity. He read the PDP-8 manual from cover to cover, soaking up the information about instruction sets, registers, bits, and Boolean algebra. He studied the manuals for the chips inside the PDP-8. Confident of his newfound expertise, within weeks Woz began drawing up plans for his own version of the PDP-8.

“I designed most of the PDP-8 on paper just for the heck of it. Then I started looking for other computer manuals. I would redesign each [computer] over and over, trying to reduce my chip count, and using newer and newer TTL chips in my designs. I never had a way to get the chips to build one of these designs as my own.”

He knew that he was going to build computers himself one day—he hadn’t the slightest doubt of that. But he wanted to build them now.

During the years Steve Wozniak attended Homestead High, semiconductor technology advances made possible the creation of minicomputers like the PDP-8. The PDP-8 was one of the most popular, while the Nova, produced by Data General in 1969, was one of the most elegant. Woz was enchanted by the Nova. He loved the way its programmers had packed so much power into a few simple instructions. The Data General software was not just powerful; it was beautiful. The computer’s chassis also appealed to him. While his buddies were plastering posters of rock stars on their bedroom walls, Woz covered his with photos of the Nova and brochures from Data General. He then decided—and it became the biggest goal in his life—that he would one day own his own computer.

Woz was not the only student in Silicon Valley with electronics dreams. Many of his fellow students at Homestead High had parents in the electronics industry. Having grown up with new technology around them, these kids were accustomed to watching their parents play around with oscilloscopes and soldering irons in the garage. And Homestead High had teachers who encouraged their students’ interests in technology. Woz may have followed his dream more single-mindedly than the others, but the dream was not his alone.

The dream was, however, highly unrealistic. In 1969, it was almost unthinkable that individuals could own their own computers. Even minicomputers like the Nova and the PDP-8 were priced to sell to research laboratories. Nevertheless, Woz went on dreaming. He did well on his college entrance exams but hadn’t given much thought to which college to attend. When he eventually made his choice, it had nothing to do with academics. On a visit to the University of Colorado with some friends, the California boy saw snow for the first time and was enchanted. He concluded that Colorado would suffice. His father agreed he could go there for a year, at least.

At the University of Colorado, Woz played bridge intensely, designed more computers on paper, and engineered pranks. After creating a device to jam the television in his college dorm, he told trusting hallmates that the television was badly grounded, and they would have to move the outside antenna around until they got a clear picture. When he had one of them on the roof in a sufficiently awkward position, he quietly turned off his jammer and restored the television reception. His hallmate remained contorted on the roof, for the public good, until the prank was revealed.

Woz took a graduate computer class and got an A+. But the computer center allocated the computer’s time jealously and Woz wrote so many programs that he ran his class over its computer-time budget by a large multiple. His professor instructed the computer center to bill him. Woz was afraid to tell his parents and he never went back to school there. After his first year, he came home and attended a local college. For a summer job in 1971, he worked at a small computer company called Tenet Incorporated that built a medium-scale computer. He enjoyed it enough to stay on into the fall rather than returning to school.

The same summer he started work, Woz and his old high school friend Bill Fernandez actually built a computer out of parts rejected by local manufacturers because of cosmetic defects. Woz and Fernandez stayed up late cataloging the parts on the Fernandez family’s living-room carpet. Within a week, Woz showed up at his friend’s house with a cryptic penciled diagram. “This is a computer,” Woz told Fernandez. “Let’s build it.” They worked far into the night, soldering connections and drinking cream soda. When they finished, they named their creation the Cream Soda Computer; it had the same sort of lights and switches as the Altair would more than three years later.

Woz and Fernandez telephoned the local newspaper to boast about their computer. A reporter and a photographer arrived at the Fernandez house, sniffing out a possible “local prodigy” cover story. But when Woz and Fernandez plugged in the Cream Soda Computer and began to run a program, the power supply overheated. The computer literally went up in smoke, and with it Woz’s chance for fame, at least for the moment. Woz laughed the incident off and went back to his paper designs.

The Two Steves Meet

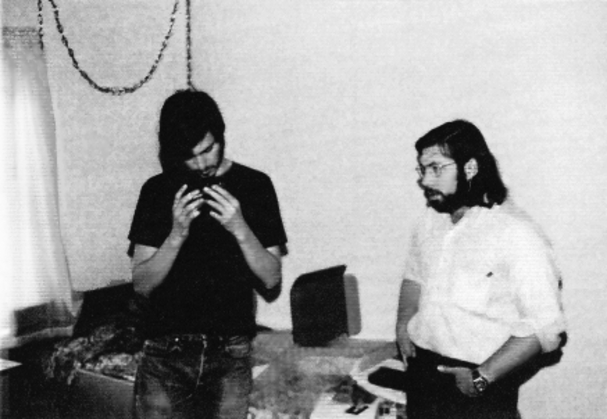

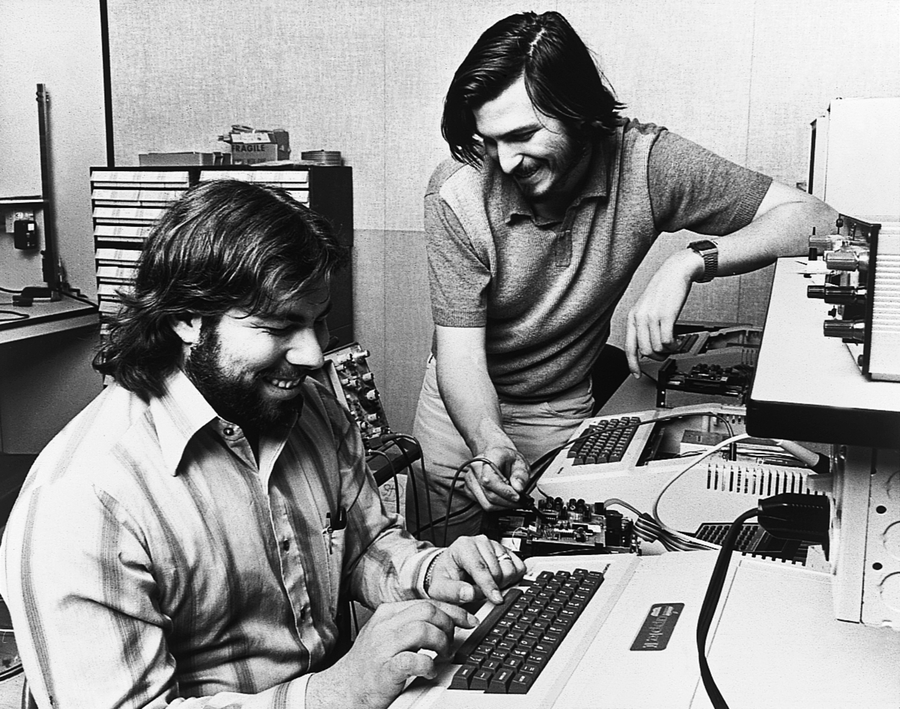

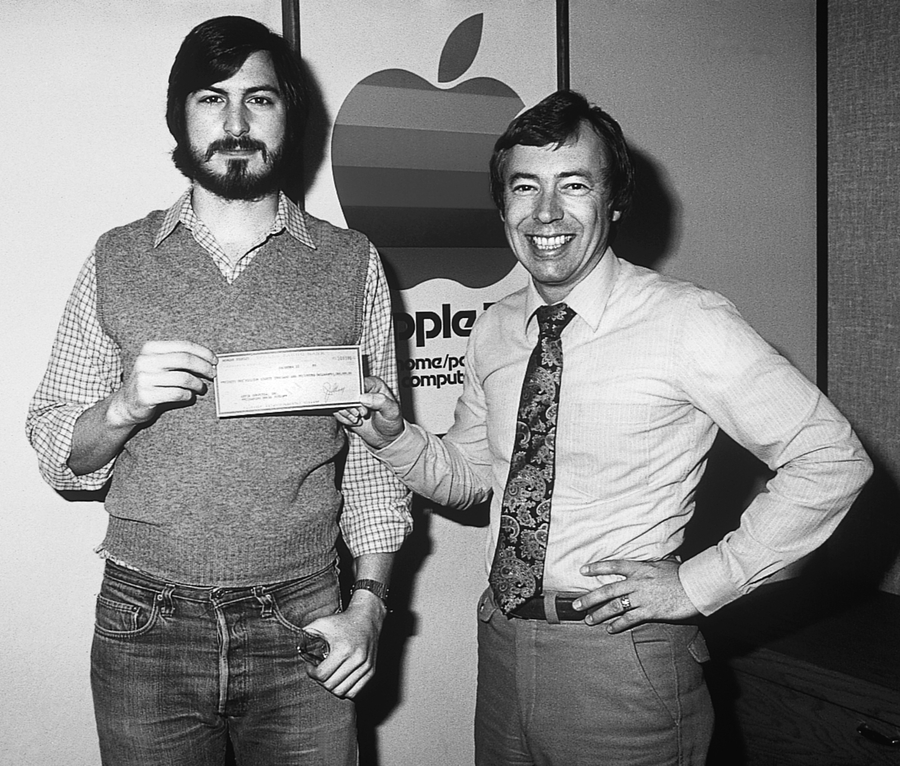

Figure 54. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak Jobs and Woz look over an early Apple I circuit board. (Courtesy of Margaret Kern Wozniak)

Besides assisting with the Cream Soda Computer, Bill Fernandez did something that would profoundly change the life of his friend. He introduced Woz to another electronics hobbyist, an old friend of his from junior high school. Although a good number of Silicon Valley students were interested in electronics because their parents were engineers, this friend, a couple of years behind Fernandez in school, was an anomaly in that respect. His parents were blue-collar workers, unconnected to the computer industry. This friend, a quiet, intense, long-haired boy, was named Steven Paul Jobs.

Although Jobs was five years younger than Woz, the two hit it off immediately. Both were fascinated with electronics. In Woz’s case, this led to the concentrated study of schematics and manuals and lengthy sessions designing electronic gadgets. Jobs was as intense as Woz, but his passion showed itself in different ways, and it sometimes got him into trouble.

Jobs confessed to being a terror as a child. He claimed that he would have “ended up in jail” if it hadn’t been for a teacher, Mrs. Hill, who moved him ahead a year to separate him from a boisterous buddy. Mrs. Hill also bribed Jobs to study. “In just two weeks, she had figured me out,” Jobs recalled. “She told me she’d give me five dollars to finish a workbook.” Later, she bought him a camera kit. He learned a lot that year.

As an adolescent, Jobs had an unshakable self-confidence. When he ran out of parts for an electronics project he was working on, he simply picked up the phone and called William Hewlett, cofounder of Hewlett-Packard. “I’m Steve Jobs,” he told Hewlett, “and I was wondering if you had any spare parts I could use to build a frequency counter.” Hewlett was understandably taken aback by the call, but Jobs got his parts. The 12-year-old was not only very convincing but also surprisingly enterprising. He made money at Homestead High by buying a broken stereo or other piece of electronic equipment, fixing it, and selling it at a profit.

But it was a mutual love of practical jokes that cemented the relationship. Jobs, Woz discovered, was another born prankster. This led the two to engage in a rather shady early business enterprise.

Blue Boxes

Woz returned to school, this time to the University of California at Berkeley, to study engineering. He had resolved to take school more seriously and even enrolled in several graduate courses. He did well, even though by the end of the school year he was spending most of his time with Steve Jobs building blue boxes.

Woz first learned about these sneaky devices for tricking the phone network and making free long-distance phone calls in a piece in Esquire magazine. The story described a colorful character who used such a device as he crisscrossed the country in his van, the FBI panting in pursuit. Although the story was a blend of fiction and truth, the descriptions of the blue box sounded very plausible to the budding engineer. Before Woz even finished the piece, he was on the phone to Steve Jobs, reading him the juicy parts.

The Esquire story was drawn from the extraordinary real-life experiences of John Draper, a.k.a. Captain Crunch. Draper had discovered that a whistle included in boxes of Cap’n Crunch cereal had an interesting ability. Blow the whistle directly into a telephone receiver and it would exactly mimic the tones that caused the central telephone circuitry to release a long-distance trunk line. With it, you could make long-distance calls for free.

Draper expanded on this trick with electronics, essentially inventing phone phreaking and becoming its prime practitioner, traveling around the country showing people how to build and operate these blue boxes. True phreaking, purists said, was motivated solely by the intellectual challenge of getting past a complex network of circuits and switches. The telephone company, however, took a dim view of the enterprise and prosecuted the phreaks whenever it could catch them.

With his customary thoroughness, Wozniak collected articles on phone-phreaking devices of all kinds. In a few months, he had become a phone-phreaking expert himself, known to insiders by the nickname Berkeley Blue. Perhaps it was inevitable that Woz’s newfound infamy would get back to the man who had inspired him. One night a van pulled up outside Woz’s dorm.

Wozniak was thrilled to meet John Draper. The two quickly became good friends, and together they used phone-phreak techniques to tap information from computers all over the United States. At least once they listened in on an FBI phone conversation, according to Wozniak.

It was Jobs, however, who made this pastime turn a profit. Jobs got into phone phreaking, too, later claiming that he and Woz had called around the world several times and once woke the Pope with a blue-box call. Soon Wozniak and Jobs had a neat little business marketing phone-phreaking boxes. “We sold a ton of ’em,” Woz would later confess. When Jobs was still in high school, Woz made most of the sales to students in the Berkeley dorms. In the fall of 1972, when Jobs entered Reed College in Oregon, they were able to broaden their market.

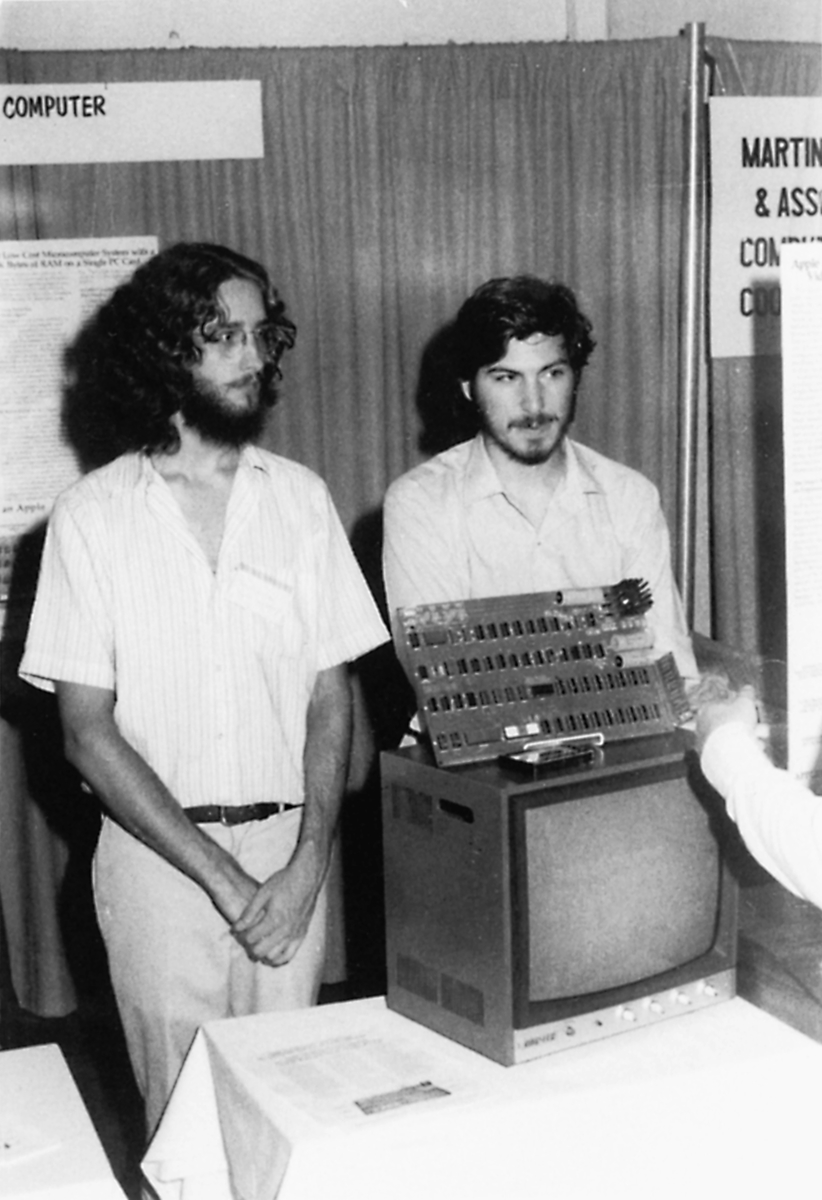

Figure 55. Dan Kottke and Steve Jobs Kottke traveled to India with Jobs and later worked for Apple. Here he and Jobs are manning the booth at an early computer show. (Courtesy of Dan Kottke)

Buddhism

Jobs had considered going to Stanford, where he had attended some classes during high school. “But everyone there knew what they wanted to do with their lives,” he said. “And I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life at all.” On a trip to Reed, he had fallen in love with the school, seeing it as a place where “nobody knew what they were going to do. They were trying to find out about life.” When Reed accepted him, he was ecstatic.

But once at Reed, Jobs lived as a recluse. As the son of working-class parents, he may have felt out of place in a school populated largely by upper-class youths. He began investigating Eastern religions, staying up late at night with his friend Dan Kottke to discuss Buddhism. They devoured dozens of books on philosophy and religion, and at one point Jobs became interested in primal therapy.

In the year Jobs spent at Reed, he seldom attended class. After six months, he dropped out but managed to remain in the dorm. “The school sort of gave me an unofficial scholarship. They let me live on campus and looked the other way.” He remained for over a year, attending classes when he felt like it, spending much of his time studying philosophy and meditating. He converted to vegetarianism and lived on Roman Meal cereal, a box of which cost less than 50 cents and would feed him for a week. At parties he tended to sit quietly in a corner. Jobs seemed to be clearing things out of his life, searching for some utter simplicity.

Although Woz had little interest in Jobs’s nontechnical pursuits, his friendship with Jobs remained strong. Woz frequently drove up to Oregon on weekends to visit Jobs.

Breakout

Woz took a summer job in 1973 at Hewlett-Packard, joining Bill Fernandez, who was already working there. Woz had only just finished his junior year, but the lure of Silicon Valley’s most prestigious electronics company was hard to resist. College would have to wait once again as Woz continued his education in the firm’s calculator division. This was the pre-Altair era when calculators were a hot commodity, and HP was manufacturing the HP-35 programmable calculator. Wozniak realized just how much the device resembled a computer. “It had this little chip, serial registers, and an instruction set,” he thought. “Except for its I/O, it’s a computer.” He studied the calculator design with the same energy that he had applied to the minicomputers of his high-school days.

After his year at Reed College, Jobs returned to Silicon Valley and took a job with a young video-game company called Atari. He stayed until he had saved enough money for a trip to India that he and Dan Kottke had planned. The two had long discussions about the Kainchi Ashram and its famous inhabitant, Neem Karoli Baba, a holy man described in the popular book Be Here Now. Jobs rendezvoused with Kottke in India, and together they searched for the ashram. When they learned that Neem Karoli Baba had died, they drifted around India, reading and talking about philosophy.

When Kottke ran out of money, Jobs gave him several hundred dollars. Kottke went on a meditation retreat for a month. Jobs didn’t go with him, but instead wandered the subcontinent for a few months before returning to California. On his return, Jobs went back to work for Atari and reconnected with his friend Woz, who was still at HP. Jobs himself had worked at Hewlett-Packard years before, on the strength of that brazen phone call to Bill Hewlett asking for spare parts. Now he was at Atari, and though he was still just as brash and just as convinced that he could get anything he wanted, he had been changed in subtle ways by his year at Reed and his experiences in India.

Woz was still a jokester at heart. Every morning before he left for work he would change the outgoing message on his telephone answering machine. In a gravelly voice and thick accent, he would recite his Polish joke for the day. Woz’s Dial-A-Joke phone number became the most frequently called phone number in the San Francisco Bay Area, and he had to argue more than once with the telephone company to keep it going. The Polish American Congress sent him a letter asking him to cease and desist with the jokes, even though Woz himself was of Polish extraction. So Wozniak simply made Italians the butt of his jokes instead. When the attention faded, he went back to Polish jokes.

In the early 1970s, computer arcade games were becoming popular. When Woz spotted one of those games, Pong, in a bowling alley, he was inspired. “I can make one of those,” he thought, and immediately went home and designed a video game. Even though its marketability was questionable (when a player missed the moving blip, “OH SHIT” flashed on the screen), the programming on the game was first-rate. When Woz demonstrated his game for Atari, the company offered him a job on the spot. Being comfortable with his position at HP, Woz turned them down.

But he was devoting much of his time to Atari technology. Woz had already dropped a small fortune in quarters into arcade games when Jobs, who often worked nights, began sneaking him into the Atari factory. Woz could play the games for free, sometimes for eight hours at a stretch. It worked out well for Jobs, too. “If I had a problem, I’d say, ‘Hey, Woz,’ and he’d come and help me.”

At the time, Atari wanted to produce a new game, and company founder Nolan Bushnell gave Jobs his ideas for what came to be called Breakout, a fast-paced game in which the player controls a paddle to hit a ball that breaks through a wall, piece by piece. Jobs boasted he could design the game in four days, secretly planning to enlist Woz’s help.

Jobs was always very persuasive, but in this case he didn’t have to bring out the thumbscrews to get his friend to help him. Woz stayed up for four straight nights designing the game, and still managed to put in his regular hours at Hewlett-Packard. In the daytime, Jobs would work at putting the device together, and at night Woz would examine what he’d done and perfect the design. They finished it in four days.

The experience taught them something: they could work well together on a tough project with a tight deadline and succeed.

Woz also learned something else, but not until much later. The $350 Jobs gave Woz as his share for the work was considerably less than the $6,650 cut that Jobs kept for himself. With Jobs, friendship only went so far.

Starting Apple

I met the two Steves. They showed me the Apple I. I thought they were really right on.

—Mike Markkula

Jobs and Woz had discovered that they were a good team. Jobs, inspired by the blue box and Breakout experiences, was eager to find a way to make this pay off. But the inspiration would have to come from Woz, and it was Homebrew that gave him that inspiration.

Woz Discovers Homebrew

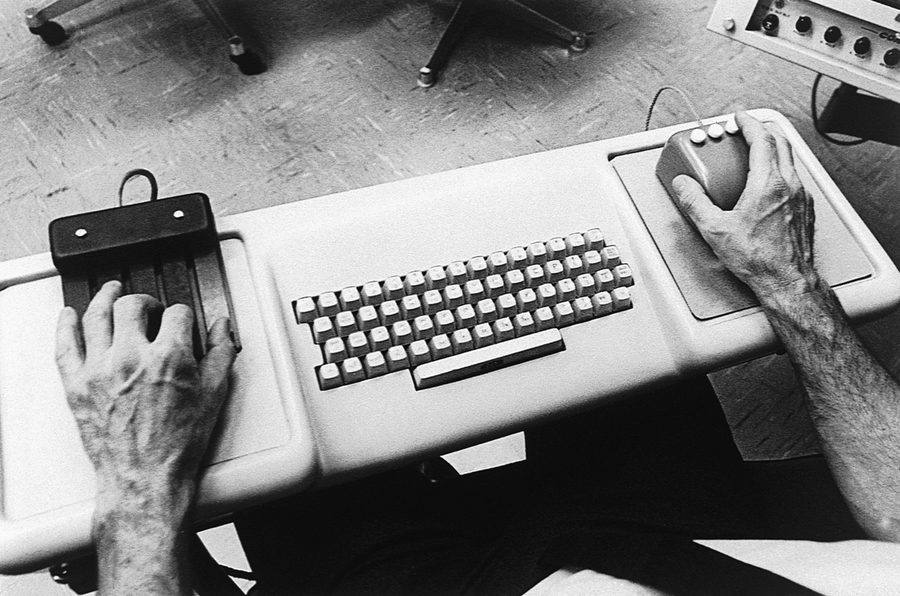

Breakout wasn’t Woz’s only extracurricular project while at HP. He also designed and built a computer terminal. Jobs had heard that a local company that rented computer time needed an inexpensive home terminal to access the company’s large computer. Jobs told Woz about it, and Woz designed a small device that used a television set for a display, much like Don Lancaster’s TV Typewriter. More significantly, around this same time Woz began attending the Homebrew Computer Club meetings.

Homebrew was a revelation for Woz. For the first time, he found himself surrounded by people who shared his love for computers, and who were more knowledgeable about computers than any of his friends, or sometimes even himself. He attended his first Homebrew meeting only because a friend of his at HP told him a new club was forming for people interested in computer terminals. When he first arrived at Gordon French’s suburban garage, he felt a little out of place. Club members were talking about the latest chips, the 8008 and the 8080, and Woz was unfamiliar with them. There, too, he learned about this new computer an individual could actually buy, called the Altair. Club members were interested in the video terminal he designed, however, and that encouraged Woz. He went home and studied up on the latest microprocessor chips. He bought the first issue of Byte and made it a point to attend the biweekly Homebrew Computer Club meetings.

Woz was inspired by Jim Warren’s and Lee Felsenstein’s visions that these devices could and should be used for social good. These things could help stop wars, he thought as he listened to Felsenstein talk about using computers for the antiwar movement.

“It changed my life,” Woz recalled. “My interest in computers was renewed. Every two weeks the club meeting was the biggest thing in my life.” And Woz’s enthusiasm, in turn, invigorated the club. His technical expertise and innocent, friendly manner attracted people to him. He quickly developed a following. For two younger club members—Randy Wigginton and Chris Espinosa—Woz became the prime source of technical information, as well as their ride to meetings. (They didn’t have their driver’s licenses yet.)

Woz couldn’t afford an Altair, but he watched with fascination as others brought theirs to the gatherings. He was impressed by the way Lee Felsenstein chaired the meetings. He realized that many of the home-built machines shown at the club resembled his Cream Soda Computer, and he began to feel that he could improve on their basic designs. But the 8080 was out of his price range. What he needed was a low-cost chip.

Then he learned that MOS Technology was going to sell samples of its new 6502 microprocessor chip at the upcoming Wescon electronics show in San Francisco for only $20. At the time, microprocessors were generally sold only to companies that had established accounts with the semiconductor houses, and they cost hundreds of dollars apiece. The Wescon show did not permit sales on the exhibit floor, so Chuck Peddle, the designer of the 6502, rented a hotel room to make the sales. Woz walked in, gave his 20 bucks to Chuck Peddle’s wife, who was handling the transactions, and went to work.

Designing the Apple I

Before designing the computer, Woz wrote a programming language for it. BASIC was the hit of the Homebrew Computer Club, and he knew he could impress his friends if he could get BASIC to work on his machine. “I’m going to be the first one to have BASIC for the 6502,” he thought. “I can whip it out in a few weeks and I’ll zap the world with it.” He did wrap it up in a few weeks, and when he finished, he set to work making something for it to run on. He considered that the easy part: he already had experience building a computer.

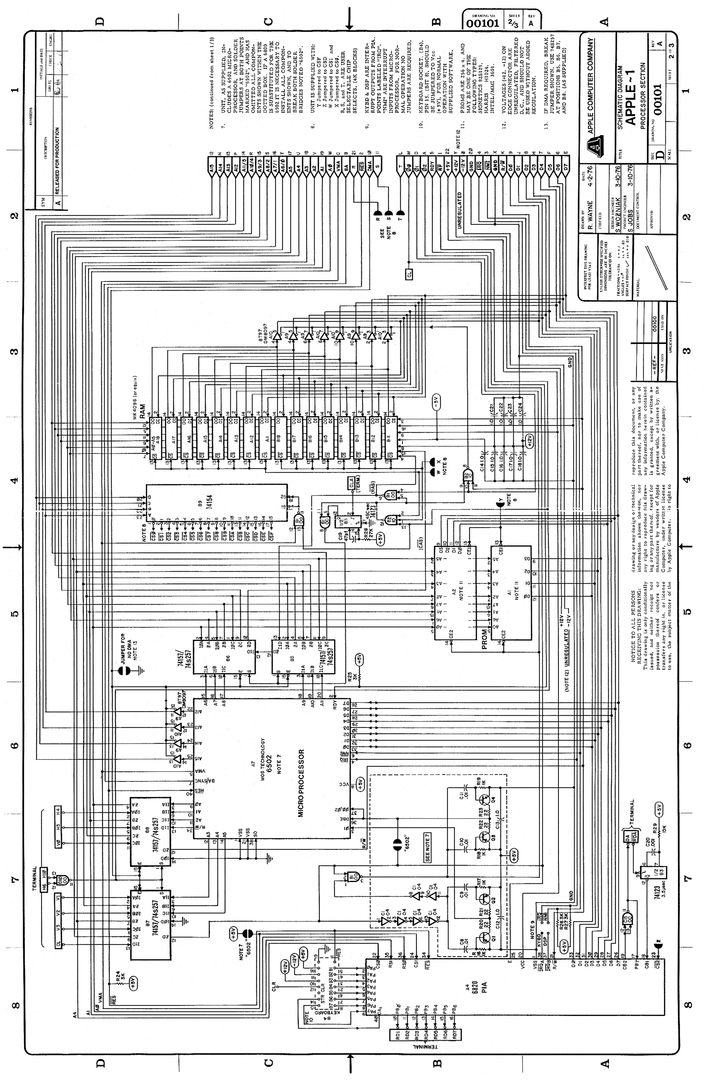

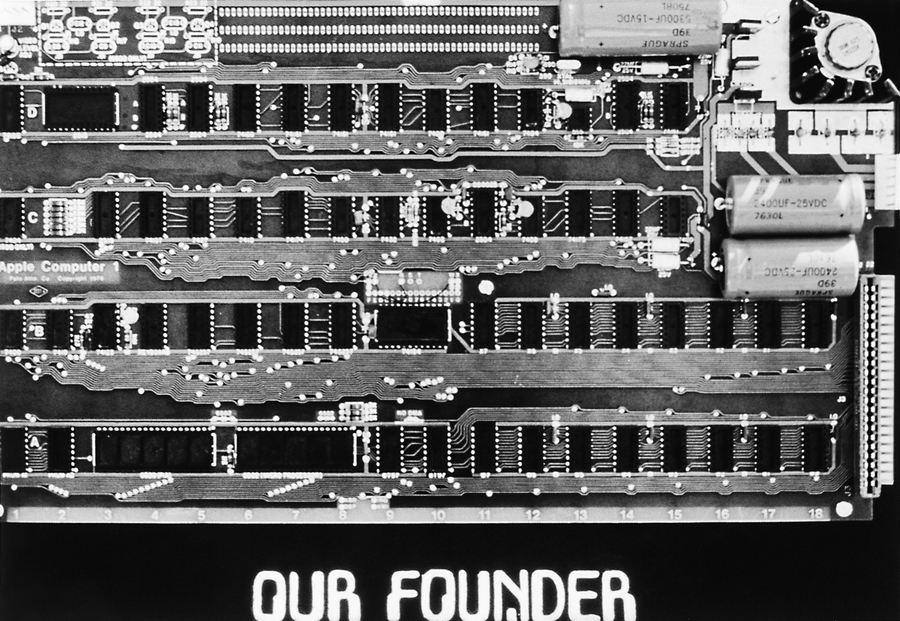

Figure 56. The Apple I schematic Many engineers consider this design by Wozniak a work of art. (Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

Woz designed a board that included the 6502 processor and interfaces connecting the processor to a keyboard and video monitor. This was no mean feat. The Intel 8008, which Popular Electronics had ignored in publishing the groundbreaking Altair story, was arguably far more suited to be used as the brain of a computer than the 6502 processor. Nevertheless, Woz finished the computer within a few weeks. Woz took his computer to Homebrew and passed out photocopies of his design. The design was so simple that he could describe it in just one page and anyone who read the description could duplicate his design. The consummate hobbyist, Woz believed in sharing information. The other hobbyists were duly impressed. Some questioned his choice of processor, but no one argued with the processor’s $20 price tag. He called his machine an Apple.

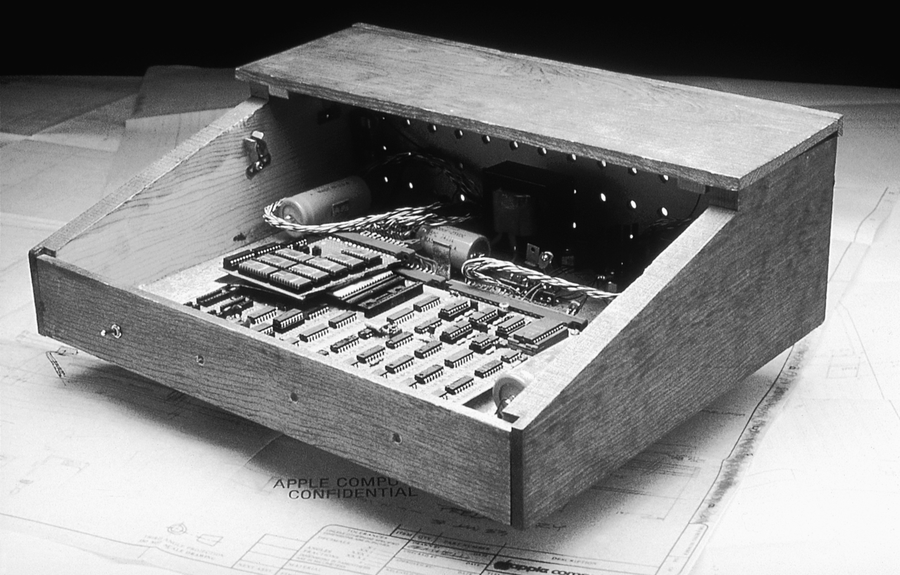

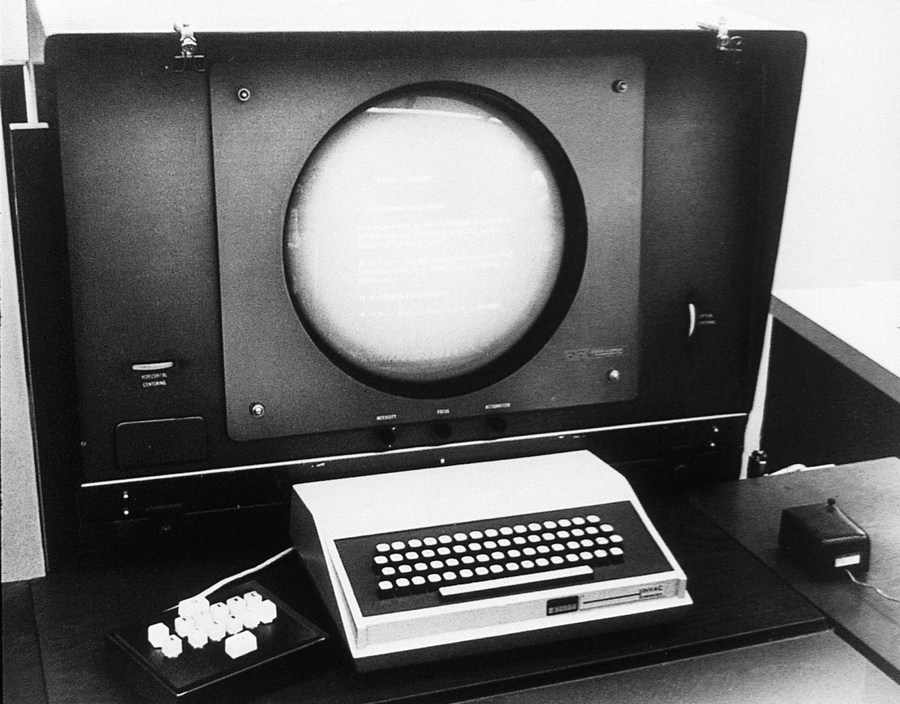

Figure 57. The Apple I Steve Wozniak’s original Apple I was a circuit board.

(Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

The Apple I had only the bare essentials. It lacked a case, a keyboard, and a power supply. The hobbyist owner had to connect a transformer to it in order to get it to work. The Apple I also required laborious assembly by hand. Woz spent a lot of time helping friends implement his design.

Steve Jobs saw a great financial opportunity in this skeletal machine, and urged Woz to start a company with him. Woz reluctantly agreed. The idea of turning his hobby into a business bothered him, but Jobs, as usual, was persistent. “Look, there’s a lot of interest at the club in what you’ve done,” he insisted. Woz conceded the point with the understanding that he wouldn’t have to leave his job at Hewlett-Packard, which he loved.

Starting a Company

Figure 58. Apple’s original logo The 1976 logo, designed by Apple cofounder Ron Wayne, features Isaac Newton under an apple tree. (Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

They founded the company on April Fool’s Day, 1976 (an appropriate date for two pranksters), together with a third partner, Ron Wayne. An Atari field service engineer, Wayne agreed to help found the company for a 10 percent stake. Wayne immediately started work on a company logo, a drawing of Isaac Newton seated under an apple tree.

Jobs sold his Volkswagen microbus and Wozniak sold his two prized HP calculators to pay for the creation of a printed circuit board. The PC board would save them the trouble of assembling and wiring each computer—a task that was forcing them to clock 60-hour work weeks. Jobs figured they would be able to sell the boards at Homebrew.

But Jobs wasn’t content to sell boards merely to hobbyists. He also began trying to interest retailers in the Apple. At a Homebrew meeting in July 1976, Woz gave a demonstration of the Apple I. Paul Terrell, one of the industry’s earliest retailers, was in attendance. Jobs gave Terrell a personal demonstration of the machine. “Take a look at this,” Jobs told Terrell. “You’re going to like what you see.”

Jobs was right. Terrell did like the machine, but he didn’t immediately place an order. When Terrell told Jobs the machine showed promise and that Jobs should keep in touch, Terrell meant what he said. The machine was interesting, but there were a lot of sharp engineers at Homebrew. This computer could be a winner, or some other machine might be better. If Jobs and Wozniak really had something, Terrell figured they’d keep in touch with him.

The next day, Jobs appeared, barefoot, at Byte Shop. “I’m keeping in touch,” he said. Terrell, impressed by his confidence and perseverance, ordered 50 Apple I computers. Visions of instant wealth flashed before Jobs’s eyes. But Terrell added a condition: he wanted the computers fully assembled. Woz and Jobs were back to their 60-hour work weeks.

The two Steves had no parts and no money to buy them, but with a purchase order from Terrell for 50 Apple I computers, they were able to obtain net 30 credit from suppliers. Jobs didn’t even know what net 30 meant. Terrell later received several calls from parts suppliers who wondered whether Jobs and Woz really had the guarantee from Terrell that they claimed they did.

Jobs and Woz were now in business. But even though they had successfully worked together under time pressure in the past, they knew they couldn’t do this task alone. The parts had to be paid for in 30 days, and that meant they had to build 50 computers and deliver them to Paul Terrell within the same time period. Jobs paid his stepsister to plug chips into the Apple I board. He also hired Dan Kottke, who was on summer break from college. “You’ve got to come out here this summer,” Jobs told Kottke. “I’ll give you a job. We’ve got this amazing thing called 30 days net.”

Terrell got his 50 Apple I machines on the 29th day, and Apple Computer was off and running. Jobs ran the business. All of the 200 or so Apple I computers eventually built were sold either through a handful of computer stores in the Bay Area or by a parcel service out of Jobs’s “home office” (initially his bedroom, and later his parents’ garage). The Apple I was priced at $666, the so-called Number of the Beast from the Book of Revelation, evidence that the prankster spirit was alive and well at Apple.

A Partner Bows Out

Unfortunately, the Apple Computer partnership wasn’t faring as well. Ron Wayne, overwhelmed by Jobs’s intensity and ambition, wanted out, and submitted his formal resignation. Jobs bought him out for $500.

By the end of the summer, Wozniak had begun work on another computer. The Apple II would have several advantages over the Apple I. Like Processor Technology’s Sol, which had not yet appeared, the Apple II would be an integrated computer, featuring a keyboard and power supply and BASIC, all within an attractive case. For output, the user could hook the computer up to a television set. Jobs and Woz made provisions to sell just the circuit board to hobbyists who wanted to customize the machine. They were both sure the Apple II would be the hit of Homebrew, but Jobs hoped it would have a much broader appeal.

After deciding on the features to include in the Apple II, Woz and Jobs argued over its price. Jobs wanted to sell the board alone for $1,200. Woz said that if the price were that high, he wanted nothing to do with it. They finally decided to charge $1,200 for the board and the case.

Now they had at least the outline of a real commercial product, and Jobs’s ambition flowered. “Steve was the hustler, the entrepreneurial type,” said Woz. Jobs wanted to build a large company, and once again he went straight to the top for help, seeking advice from Atari founder Nolan Bushnell. Bushnell, figuring that Apple needed a money guy in their corner, introduced Jobs to Don Valentine, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist. Valentine suggested that Jobs talk to a friend of his named Mike Markkula.

A Partner Signs On

In the busy two years after the introduction of the Altair, the microcomputer industry had reached a critical turning point. Dozens of companies had come and gone. MITS, the industry pioneer, was foundering; IMSAI, Processor Technology, and a few other companies were jockeying for control of the market even as they faltered. Before long, all these companies failed.

In some cases, the failure of these early companies stemmed from technical problems with the computers, but more often it was a lack of expertise in management and in marketing, distributing, and selling the products that did in these companies. Their corporate leaders were primarily engineers, not managers; they weren’t versed in the ways of business, and often alienated their customers and dealers. MITS drove retailers away by forbidding them to sell other companies’ products; IMSAI ignored dealer and customer complaints about defects in its machines; and Processor Technology responded to design problems with a bewildering series of slightly different versions, failed to keep pace with advances in the technology, and boxed itself in by refusing the venture capital needed for growth. Computer dealers eventually grew tired of these practices.

At the same time, the market was changing. Hobbyists had organized into clubs and users’ groups that met regularly in garages, basements, and school auditoriums around the country. The number of people who wanted to own computers was growing, as were the ranks of knowledgeable hobbyists who wanted “a better computer.” Unfortunately, would-be manufacturers of that “better computer” all faced one seemingly insurmountable problem: they didn’t have the money to develop such a device.

The manufacturers, usually garage enterprises, needed investment capital, but there were strong arguments against giving it to them: the high failure rate among microcomputer companies, the lack of managerial experience among their leaders, and—the ultimate puzzle—the absence of IBM from the field. Investors had to wonder, if this area of computer technology had any promise, why hadn’t IBM preempted it? In addition, some of the founders of the early companies looked unfavorably on the notion of taking money from an outside source, as that could mean losing some control of their companies.

For the microcomputer industry to continue advancing, an individual with a special perspective was needed—someone who could see beyond the basic risks to the potential rewards, right the bad management and poor dealer relations, and address the sometimes-slipshod workmanship in order to capitalize on the enormous potential of these garage entrepreneurships.

In 1976, Armas Clifford “Mike” Markkula, Jr., had been out of work for more than a year. His unemployment was self-imposed. Markkula had done well for himself during his tenure with two of the most successful chip manufacturers in the country, Fairchild and Intel, largely because he was uniquely suited to the work. Although a trained electrical engineer who understood the possibilities of the microprocessor, at Intel he worked in the marketing department, where he was considered a wizard. Beyond the excitement of being around emerging technology, Markkula enjoyed forging ahead with a large company in a competitive environment.

Outside the hobbyist community, few people understood the potential of microprocessor-based technology as well as Mike Markkula did. With his rare combination of business savvy and engineering background, Markkula was just the person microcomputer companies needed to promote their technology, if any could afford him.

Markkula had retired from Intel in his early thirties with stock options that made him a millionaire. He planned a leisurely existence, and he convinced himself that after the breakneck pace of life in the semiconductor industry, he could be happy learning to play the guitar and going skiing at his cabin near Lake Tahoe. Friends may have observed that his investments in wildcat oil wells did not bespeak a full commitment to the idle life, but Markkula was adamant about being out of the rat race for good.

Nevertheless, in October 1976, at Don Valentine’s suggestion, Markkula visited Jobs’s garage. He liked what he saw. It made sense to provide computing power to individuals in the home and workplace, and these boys had a good product. When Markkula offered to help them draw up a business plan, he told himself he wasn’t violating his resolve to stay retired—he was just giving advice to two sharp kids. He was doing it more for pleasure than business, he rationalized, as Jobs and Woz couldn’t afford to pay him what a consultant with his experience would normally get.

But within a few months, Markkula decided to throw in with these two kids. He assessed Jobs and Woz’s equity in the company at about $5,000. He put up a considerably larger chunk of money himself, promising Apple up to $250,000 of his own money, and then investing $92,000 to buy himself a one-third interest in the company. Jobs and Woz were stunned by Markkula’s assurance that they each owned a third of a nearly $300,000 company.

Why did this 34-year-old retired executive throw in his lot with two long-haired novices who had no collateral except their ingenuity, ambition, and creative ideas? Even Markkula couldn’t answer the question satisfactorily, but he had become convinced—and hooked on the idea—that he could take Apple to the Fortune 500 in five years.

The first decision Markkula made was to keep the name Apple. From a marketing standpoint, he recognized the simple advantage of being first in the phone book. He also believed that the word apple, unlike the word computer, had a positive connotation. “Very few people don’t like apples,” he said. Furthermore, he liked the incongruous pairing of the words apple and computer, and believed it would be good for name recognition.

Then he set out to turn Apple into a real company. He helped Jobs with the business plan and obtained a line of credit for Apple at the Bank of America. He told Woz and Jobs that neither of them had the experience to run a company and hired a president: Michael Scott, nicknamed Scotty, a seasoned executive who had worked for him at Fairchild.

Designing the Apple II

By the fall of 1976, Woz had already made progress on the design of his new computer. The Apple II would embody all the engineering savvy he could bring to it. It would be the embodiment of Steve Wozniak’s dream computer, one he would like to own himself. He had made it considerably faster than the Apple I. There was a clever trick he wanted to try that would give the machine a color display, too.

Wozniak was skittish about forming a company from the start, and now he was worried about working full time for it. He had always enjoyed his job at Hewlett-Packard. HP was legendary among engineers for its commitment to quality design. It seemed crazy to give up a job at HP. Still…

Woz had shown his Apple I design to the managers at Hewlett-Packard with the hope that he could convince the company to build it. But they told him that the Apple was not a viable product for HP, and gave him a release to build the machine on his own. He’d also attempted, twice, to join computer-development projects at HP—the project that eventually developed into the HP 75 computer and a handheld BASIC machine—and, lacking the experience and the academic credentials HP expected, was turned down for both.

Wozniak was unarguably an outstanding engineer, but he really wanted to work on projects that interested him, and then only for as long as they interested him. Jobs understood his friend’s restless genius better than anyone. He constantly urged Woz on, and the pressure sometimes led to arguments.

Woz had no interest in designing the connector for hooking the computer up to the television set, nor did he want to design the power supply. Both tasks required skill in analog electronics. The digital circuitry of a computer basically comes down to power on or off, a 1 or a 0. To design a power supply or send a signal to a television set, an engineer has to consider voltage levels and interference effects, things Woz didn’t know or care about.

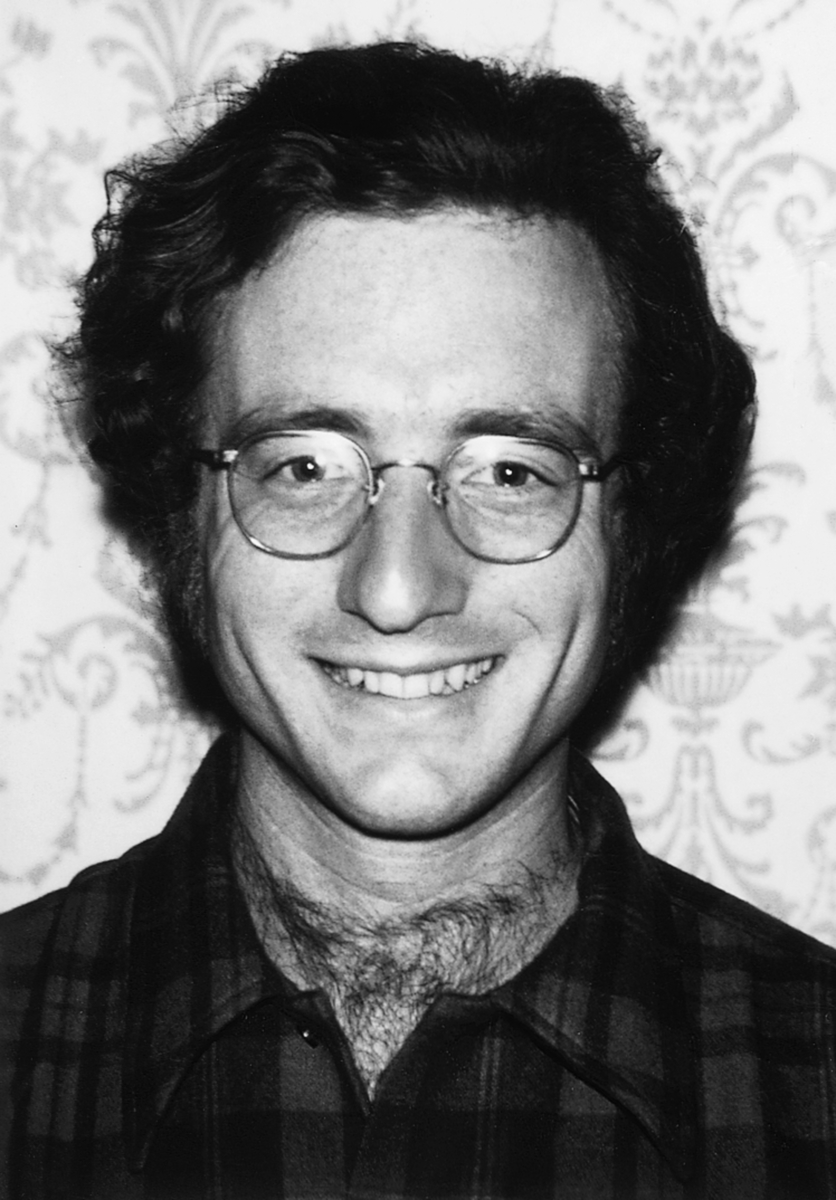

The Everything-Else Guy

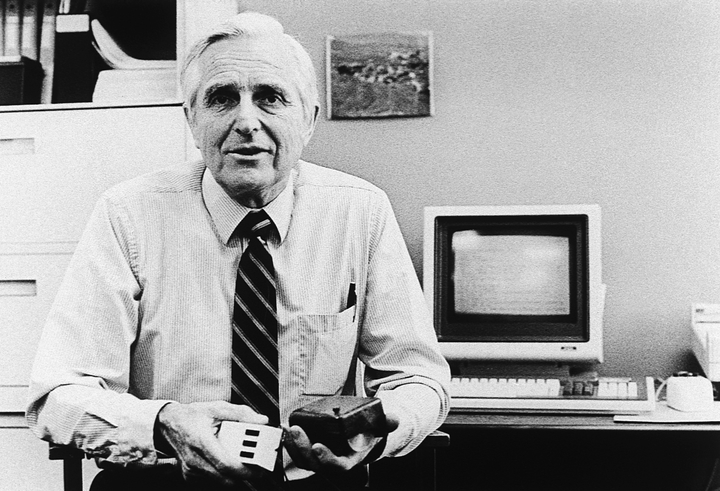

Figure 59. Rod Holt Holt, an early hire at Apple, wore many hats. (Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

Jobs turned to Al Alcorn, his boss at Atari, for help, and Alcorn suggested that Jobs talk to Rod Holt, a sharp analog engineer at Atari. When Jobs phoned Holt in the fall of 1976, Holt was feeling dissatisfied with his position at Atari. “I was a second-string quarterback,” he said. Holt suspected he had been hired just in case his manager, whose hobby was racing motorcycles, got hurt. But Holt was skeptical of Jobs. He had a daughter older than Steve Jobs. And he had trouble understanding the West Coast culture that shaped Apple’s founders.

Holt told Jobs that as an Atari engineer, his helping Apple represented a conflict of interest. Besides, he added, he was expensive. His services ran at least $200 a day. That didn’t faze Jobs. “We can afford you,” he said. “Absolutely.” Holt liked the brashness. Regarding the conflict of interest, Jobs told him to check with his boss. Alcorn told Holt, “Help the kids out.”

Holt started working after hours at Atari on Apple’s television interface and power supply, concentrating especially on the latter. He persuaded Jobs not to challenge FCC regulations by trying to build an interface for a television set. Holt knew that the FCC would hassle them over interference. Jobs was frustrated at first, but then hit on a clever way out of the problem: just make it easy for someone else to design the modulators to link the computer to a television set. If regulations got bent, the culprit wouldn’t be Apple.

Soon Holt was on board full time. Wherever no one else had the technical or managerial expertise to solve a problem, Holt took care of it. “I was the everything-else guy,” he said. As the company began growing faster than even Markkula had hoped, Holt found that he was overseeing the quality-control department, the service department, the production engineering department, and the documentation department. Things got so stressful that Holt threatened to resign several times. But he couldn’t do it. Apple was just too interesting to leave.

Rod Holt was one of the first employees of Apple once Markkula came aboard, but the real first employees date back to the Apple I era. Bill Fernandez, the friend who had introduced the Steves to each other several years earlier, was the first hire. As a formality, Jobs tested Fernandez with a series of questions about digital electronics before officially hiring him to manufacture Apple I computers. Fernandez practiced the Bahai faith and he and Jobs spent many hours discussing religion in Jobs’s garage that doubled as their workshop.

Other early employees included high-school students Chris Espinosa and Randy Wigginton, Woz’s friends from the Homebrew meetings. After the meetings, the trio routinely headed to Woz’s house to continue discussing ways to improve the capabilities of the Apple I to turn it into something more powerful.

Espinosa and Wigginton were software hackers. They had no special expertise in designing machines. Instead, they loved writing programs. Whenever Woz brought the Apple I to the Homebrew meetings, Espinosa and Wigginton would knock off some programs on the spot to demonstrate the machine to club members. Woz had built a working prototype of the Apple II by August of 1976, and loaned one to Espinosa, who began developing games and demonstration software for the computer. By actually using the new computer, the self-confident teenager was able to suggest ways to better its design.

Before he went to work for Apple, Espinosa spent a lot of time at Paul Terrell’s Byte Shop. He recalled that a “tall, scraggly looking guy would come in every day and say, ‘We got a new version of the BASIC!’” That was how Espinosa met Steve Jobs. Later, at Homebrew, Jobs noticed a demo program running on the Apple I. He asked Espinosa, “Did you do that?” Shortly thereafter, Espinosa was working for Apple.

Espinosa spent Christmas vacation of his sophomore year of high school in Jobs’s garage, helping debug the BASIC that would be sold with the Apple II. Jobs took him under his wing, although Espinosa’s early impression of Jobs was as something other than a paternal figure. “I thought he seemed dangerous,” Espinosa said about Jobs. “Quiet, enigmatic, almost sullen, a fierce look in his eyes. His powers of persuasion are something to be reckoned with. I always had this feeling that he was shaping me.”

Woz Waffles

Jobs then faced the biggest obstacle thus far to his legendary powers of persuasion. By this time, Markkula had agreed to join Jobs and Woz. The final hurdle was convincing Woz to leave his job at Hewlett-Packard to work full time for Apple. Markkula would have it no other way.

Woz wasn’t sure he wanted to make the move. Jobs was panicking. All of his carefully wrought plans depended on Woz. Then, one day in October 1976, Woz said that he would not leave his great job at HP, and that his decision was final. “Steve went into fits and started crying,” Woz recalled. Soon Jobs began lobbying Woz’s friends, having them call Woz to persuade him to change his mind.

Woz was afraid that designing computers full time would be drudgery, unlike the efforts he put into designing the Apple I and II. Somehow his friends convinced him otherwise, and he finally agreed to leave his job at HP and join Apple full time. It was a brave move given that Woz imagined that they would, at best, sell no more than a thousand Apple II computers.

But Jobs had an entirely different vision and aggressively set out to get people who could help him achieve it—people like Regis McKenna, owner of one of the most successful public-relations and advertising firms in Silicon Valley.

Creating an Image

Jobs had placed an ad in the computer magazine Interface Age. He’d also seen the Intel ads in various electronics magazines and was impressed enough to call the semiconductor company and ask who had done them, and got McKenna’s name. Jobs wanted the best for Apple and, deciding that McKenna was the best, set about getting his firm to handle Apple’s PR.

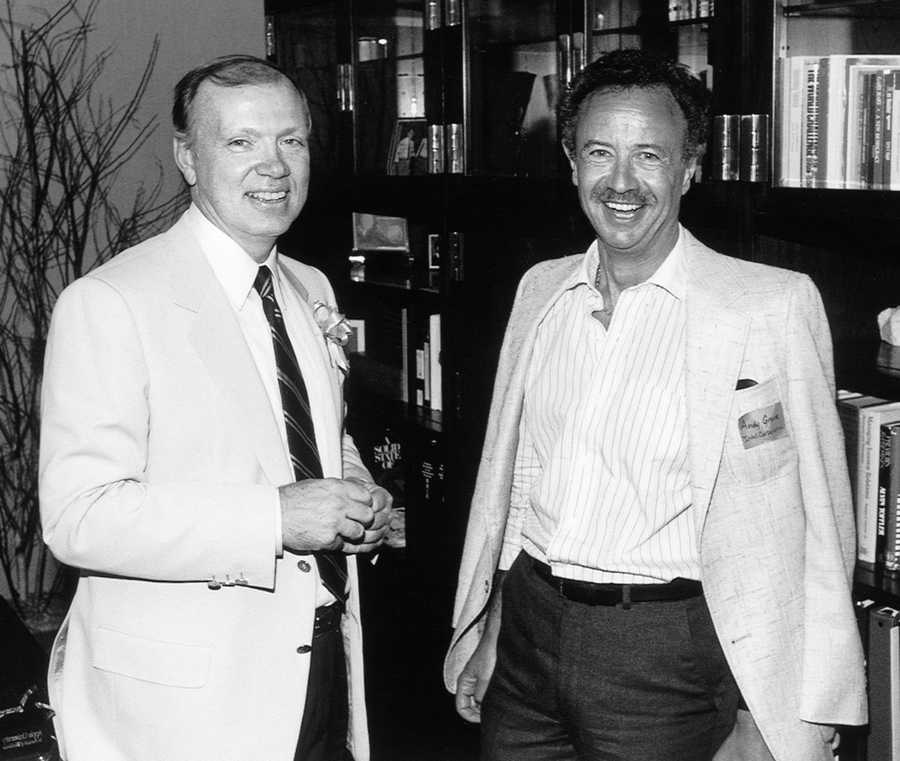

Figure 60. Regis McKenna and Andy Grove McKenna talks with Intel cofounder Andy Grove.

(Courtesy of Regis McKenna)

McKenna’s ads had been very good for Intel, as well as for McKenna himself, whose office decor spelled success. Customarily dressed in a natty suit, McKenna sat behind a large desk backed by photographs of his favorite Intel ads. He spoke softly and reflectively, in sharp contrast to the unkempt and pushy kid who walked into his office one afternoon in cutoffs, sandals, and what McKenna called a “Ho Chi Minh beard.” McKenna was accustomed to taking start-up companies as clients, so Jobs’s garb didn’t put him off. “Inventions come from individuals,” he reminded himself, “not from companies,” and this Jobs was certainly an individual.

At first McKenna said no, but that didn’t stop Jobs. “I don’t deny that Woz designed a good machine,” said McKenna. “But that machine would be sitting in hobby shops today were it not for Steve Jobs.”

McKenna eventually succumbed to Jobs’s persistence, and his agency became Apple’s PR firm. The agency immediately made two major moves.

The first was a new logo to replace Ron Wayne’s overly busy Newton under the apple tree: a rainbow-striped apple with a bite taken out of it. The logo was designed by Rob Janoff and, with variation, served as the company’s trademark ever since. From a printing standpoint, there was some initial fear that the multiple colors would run together. Jobs vetoed the addition of lines to separate the colors, making the cost of printing the logo very high. Apple president Michael Scott called it “the most expensive bloody logo ever designed.” But when the first foil labels arrived for the Apple II, everyone loved the look of the design. Jobs made one change: he rearranged the order of the colors to put the darker shades at the bottom. A later president of Apple products, Jean-Louis Gassée, would say that the logo was perfect for Apple: “It is the symbol of lust and knowledge, bitten into, all crossed with the colors of the rainbow in the wrong order…lust, knowledge, hope, and anarchy.”

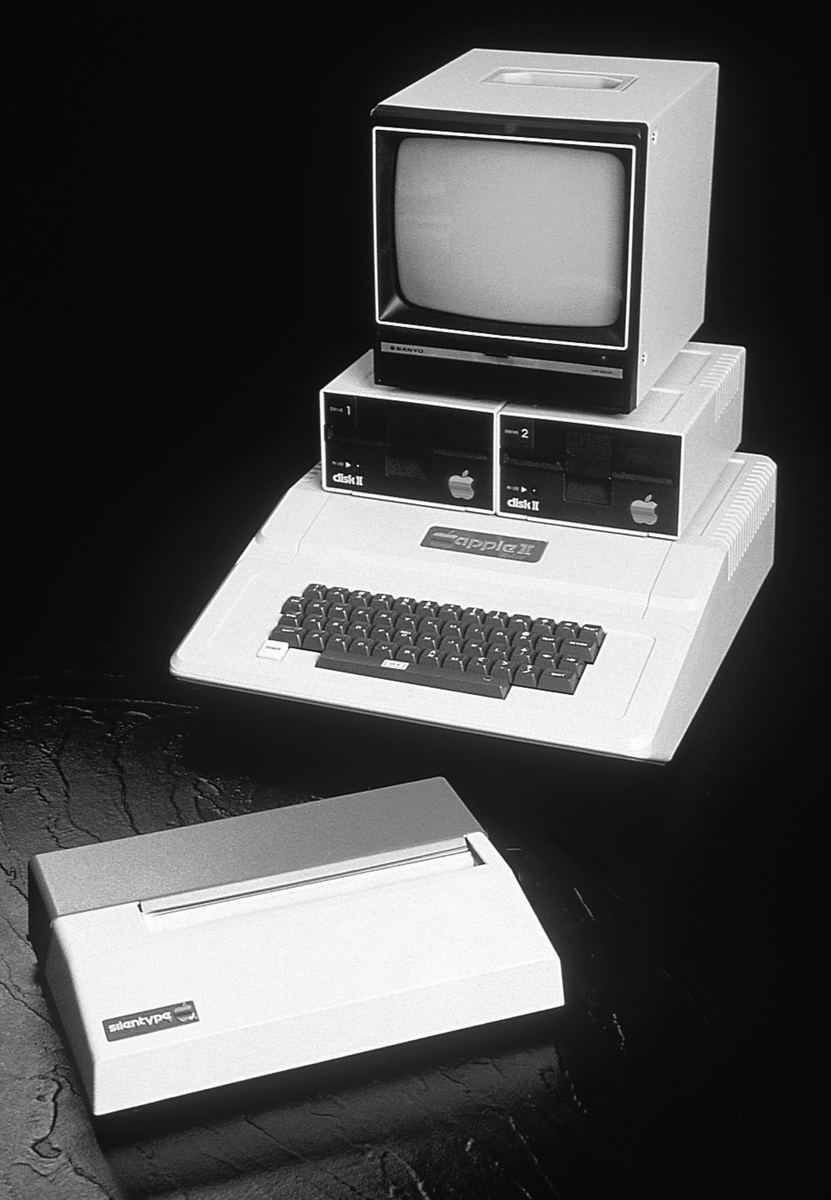

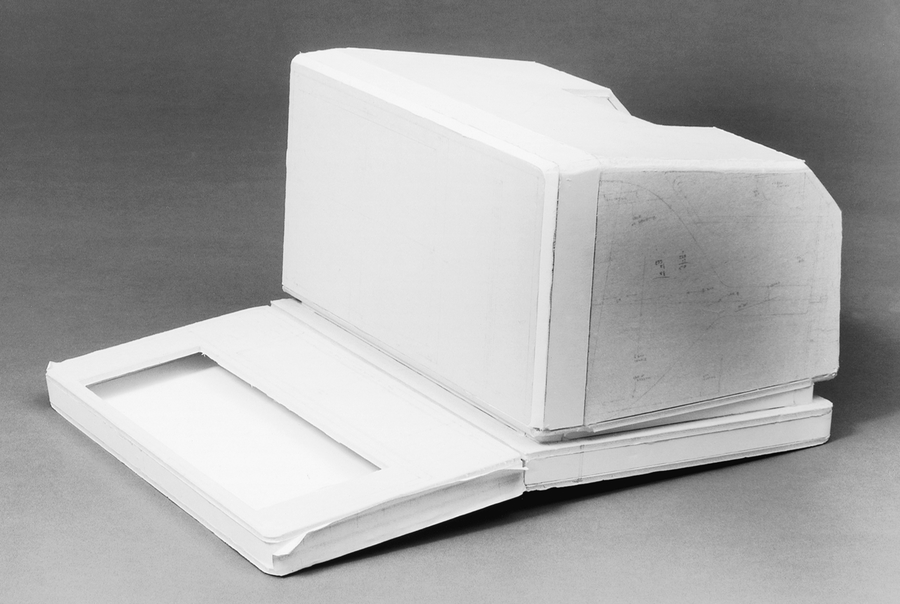

Figure 61. The Apple II This is the product that launched Apple as a serious business.

(Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

McKenna also decided to run a full-color ad in Playboy magazine. It was a bold, expensive grab for publicity. A cheaper ad in Byte would have reached virtually all the microcomputer buyers of that time, and Playboy seemed an off-the-wall choice given that there were no demographic studies to support it. “It was done to get national attention,” said McKenna, “and to popularize the idea of low-cost computers.” Other companies had been selling microcomputers for two years, but no one had yet tried to capture the public’s imagination in this way. Apple’s publicity campaign resulted in follow-up articles in national magazines, and not just about Apple, but about small computers in general.

Apple was bringing the idea of a personal computer into the mainstream consciousness.

Jobs’s persistence persuaded McKenna to buy into the Apple dream, as it had with Woz, Markkula, and Holt. Woz invented the machine, Markkula had the business sense, McKenna provided the marketing talent, Scotty ran the shop, and Holt was the everything-else guy, but the pushy kid with the scraggly beard was the driving force behind it all.

By February 1977, Apple Computer had established its first office in two large rooms a few miles from Homestead High School in Cupertino. Desks were hauled in and work benches were trundled over from Jobs’s garage. The night before they were to begin working in their new suite, Woz, Jobs, Wigginton, and Espinosa scattered around the 2,000-square-foot office playing telephone games, with each trying to buzz one of the other extensions first. The whole thing felt like play. It was hard to imagine that they were starting a real business. “We never thought that we’d grow up to be battling one-on-one with IBM,” said Espinosa.

The Debut

The young company faced a more modest challenge than tackling the company that had defined computer for generations: they had to finish the Apple II design in time for Jim Warren’s first West Coast Computer Faire in April and get it ready for production shortly thereafter. Markkula was already signing up distributors nationwide, many of whom were eager to work with a company that would give them greater freedom than microcomputer manufacturer MITS had, as well as provide a product that actually did something.

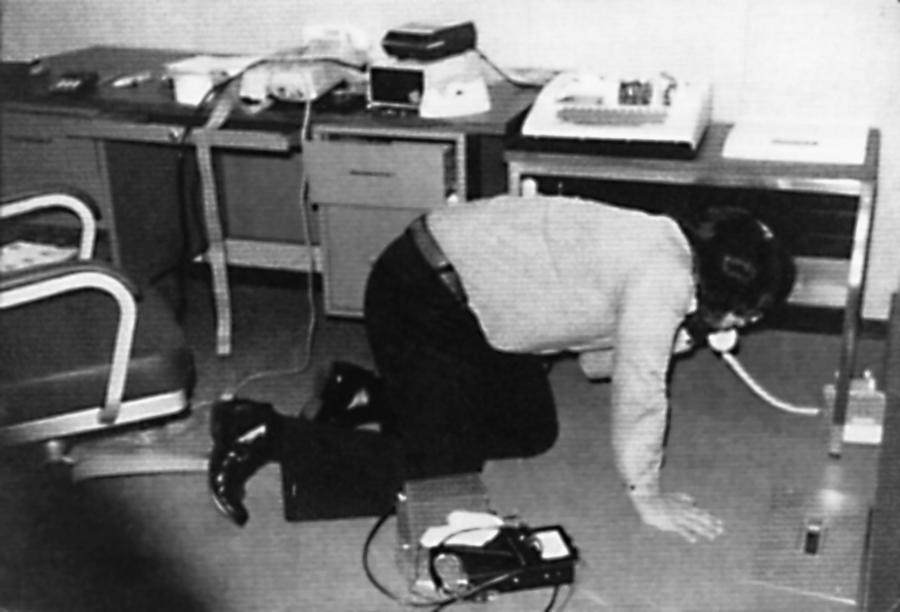

Figure 62. Steve Wozniak Woz scrambles for a phone in one of Apple’s early offices.

(Courtesy of Margaret Kern Wozniak)

Steve Wozniak is justly credited with the technical design of the Apple I and Apple II. Nevertheless, an essential contribution to making the Apple II a commercial success came from Jobs. Early microcomputers were typically drab and ugly metal boxes. Steve Jobs decided to spruce up the look of the product. He would encase the device in a lightweight beige plastic shell that melded the keyboard and computer together in a modular design. Woz could design an efficient computer, but he cheerfully admitted that he didn’t care whether or not wires were left dangling out of it. Jobs realized that the Apple had to look presentable to better the competition.

It took a gargantuan effort to ready the Apple II for the West Coast Computer Faire. Woz worked day and night, as was his modus operandi, until it was done. Jobs made sure that nobody would miss it. He arranged to have the biggest and most elegant booth at the show. He brought in a large projection screen to demonstrate programs and placed Apple II computers on either side of the booth. Jobs, Mike Scott, Chris Espinosa, and Randy Wigginton manned the booth while Mike Markkula toured the auditorium signing up dealers for the company. Woz walked around checking out other machines. All in all, the Computer Faire was a big success for Apple. Everyone seemed to like the Apple II, although Computer Lib author Ted Nelson complained that it displayed only uppercase letters.

Woz couldn’t resist playing one of his practical jokes. MITS was absent from the show, and with the help of Randy Wigginton, Woz whipped up a brochure on the “Zaltair,” supposedly an enhanced Altair computer.

“Imagine a dream machine. Imagine the computer surprise of the century, here today. Imagine BAZIC in ROM, the most complete and powerful language ever developed,” the fake advertisement purred. Woz was satirizing the marketing hype that he’d learned from Jobs. The brochure gushed on, “A computer engineer’s dream, all electronics are on a single PC card, even the 18-slot motherboard. And what a motherboard.…” On the back of the brochure was a mock performance chart comparing the Zaltair to other microcomputers—including the Apple.

Figure 63. From Altair to Zaltair One of Wozniak’s practical jokes; this one fooled Jobs.

(Courtesy of Steve Wozniak)

Jobs, knowing nothing of the joke, picked up one of the brochures and read it in dismay. He took a quick, nervous scan of the performance chart, and a look of relief came over his face. “Hey,” he said, “We came out okay on this.”

Magic Times

After the West Coast Computer Faire, we had a sense of exhilaration for having pulled off something so well, not just for Apple, but for the whole computer movement.

—Chris Espinosa

In 1977, Apple could do no wrong. It was an enchanted time for the tiny company, whose principals radiated an innocent confidence. Hobbyists praised Woz’s design, dealers clamored for the new computer, and investors were itching to sink money into the company.

Figure 64. Apple I circuit board The original Apple I circuit board was framed and hung in the Apple offices, with the legend “Our Founder.” (Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

Assembling the Team

In May, Woz reviewed Wigginton’s performance to see if he deserved a raise. His work was fine, but Woz demanded more. He found it unacceptably inefficient that he had to walk around the block to get to the next-door 7-Eleven. If Wigginton would remove a board from a fence, Woz could slip under it and Wigginton could have his raise. The next day Woz found the board on his desk, and Wigginton started earning $3.50 an hour.

Apple employee Chris Espinosa was in his first semester at Homestead High. Every Tuesday and Thursday he drove to the Apple offices on his moped, purchased with Apple earnings, because he wasn’t old enough to drive a car. There he supervised the twice-weekly public demonstrations of the Apple II. Once when representatives of Bank of America dropped by, Espinosa had to quicky replace “OH SHIT” in Woz’s implementation of the Breakout game with “THAT’S TERRIBLE.” Espinosa had a precocious air of responsibility. Jobs and Markkula were thankful that he kept the visitors engaged so that they could attend to the more important task of signing up new dealers. “For about six months, I was the sole means by which people off the street in the Bay Area would learn about Apple Computer,” Espinosa said.

It wasn’t the most professional environment, and Mike Scott was tiring of the crowd that frequently dropped in to check out Woz’s progress. Sometimes they did more than watch: Allen Baum, a close friend of Wozniak’s from Hewlett-Packard, contributed important design ideas. But if they could contribute ideas, they could just as easily swipe them. Mike Scott finally decreed that some confidentiality was necessary. He felt it was his job to instill a professional environment in Apple. Under pressure from Scotty, Baum visited less and less frequently. Scotty recognized some young talent, however, and he convinced Randy Wigginton to stay involved by offering to have Apple pay for his college education.

Mike Scott was a complex individual who was vital to Apple’s success. Unlike the dapper Mike Markkula, he was down-to-earth, boisterous, frank, and not one to hide his feelings, positive or negative. He liked to stroll through the office and chat with employees, often using maritime metaphors. He saw himself as a captain of a ship, wheel in hand at the helm. “Welcome aboard,” he would say to a new employee. When Scotty was happy, those around him were happy. According to Rod Holt, Scotty had a slush fund for special expenses, part of which paid for an enormous hot-air balloon and a sail for Holt’s yacht, each sporting the Apple logo. One Christmas, he walked around dressed in a Santa Claus suit, handing out presents to employees. But if Scotty was displeased with your performance, he let you know it.

Scott quickly grew impatient when projects were delayed. He couldn’t understand Wozniak’s irregular work habits, which swung from total dedication to headstrong avoidance, depending on his interest in the task at hand. Scotty also objected to some of Woz’s friends—like John Draper, a.k.a. Captain Crunch.

Peripheral Issues

In the fall of 1977, Draper was visiting Woz at Apple and expressed interest in helping design a digital telephone card for the Apple II. No one understood telephone technology better than Captain Crunch. Scott had granted Woz a separate office in which to work, hoping that it might encourage his creativity, and soon John Draper was working there, too.

Figure 65. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs Wozniak at the keyboard of his creation as Jobs looks on (Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

Draper and Woz constructed a device that could, among other things, dial numbers automatically and function much like a telephone answering machine. But Draper also built a blue-box capability into the card. According to Espinosa, a network of a dozen Apples equipped with Draper’s cards could bring down the nation’s entire phone system. When Scott learned that the device could be used illegally, he stalked the Apple offices in a rage.

The phone card didn’t last long after that, although, without Draper’s knowledge, modifications were being designed into the card by other engineers to nullify most of its phone-phreak capabilities. According to one Apple board member, Scott considered firing Woz after that. It wasn’t inconceivable that Scott would have made one of the company’s founders walk the plank. “Scotty is the only guy that would dare fire me,” said Woz. “That guy could do anything.” Rod Holt agreed: “Scotty could fire anybody.” All he needed was a single excuse. When John Draper was later arrested for phone phreaking, he had an Apple computer with him. The machine was confiscated, and Scotty again cursed Woz.

At the same time Woz hired Draper, Scotty recruited two other key employees. In August 1977, Gene Carter became Apple’s sales manager and Wendell Sander came on board to work under Rod Holt. An electrical engineer with a PhD from Iowa State University, Sander had years of experience in the semiconductor field. But it wasn’t his high-technology experience that convinced Apple to hire him.

Sander had bought an Apple I a year earlier and was working on a version of a Star Trek game for his teenage children to play. In the course of writing the program, he had met Steve Jobs while chasing down updated versions of the integer BASIC programming language. Jobs supplied him with the updates and in the process learned about the Star Trek program. When Jobs was getting ready to ship the first Apple IIs, he invited Sander to the company’s office and asked him to rework the program to run on the new machine. Sander met with Mike Markkula and decided that he wanted to work for the young company. After he was hired, he took a loan on his San Jose home in order to buy Apple stock. Woz, Rod Holt, and Sander made up the core of Apple’s engineering department for the remainder of 1977.

During 1977 and 1978, Woz worked on a number of accessory products that were necessary to keep Apple on stable ground during its formative years. To make the Apple II appealing to customers outside the hobbyist realm, add-on peripherals were needed. These devices enabled the machine to work with different kinds of printers and connect with modems used to transfer information from one machine to another over a telephone line.

Thanks to its small size and well-oiled internal mechanism, the company could choose and build new products more easily than many other firms. Among the most important of these items were peripheral cards: printer cards, serial cards, communications cards, and ROM cards. Woz worked on developing most of these, with Wendell Sander and Rod Holt contributing their share of the development duties.

Business was building. More and more dealers signed on, and Apple began manufacturing the Apple II. By the end of 1977, the company was making a profit and doubling production every three months. An article in Byte helped to further popularize the Apple II. Mike Markkula had also attracted investment capital from the successful New York—based firm of Venrock Associates, which was formed by the Rockefeller family to invest in high-tech enterprises. Venrock’s Arthur Rock became a member of Apple’s board of directors.

Figure 66. Regis McKenna and Arthur Rock McKenna talks here with venture capitalist Arthur Rock, one of Apple’s first investors.

(Courtesy of Regis McKenna)

By year’s end, the company moved into a larger office on nearby Bandley Drive in Cupertino. The structure felt huge, and gave the Apple employees a feeling that the firm was going to become something big. They were right. Apple soon outgrew the building and added another on the same street. Perhaps the most significant accomplishment of this period occurred during Woz’s 1977 Christmas vacation.

Beautiful Circuitry

Before the end of 1977, Woz had started working on his next big project. The idea arose from a December executive board meeting attended by Markkula, Scott, Holt, Jobs, and Woz. At the meeting, Markkula stepped forward and wrote on a board a list of goals for the company. At the top of the list, Woz saw the words “floppy disk.” “I don’t know how floppy disks work,” Woz thought.

But Woz knew Markkula was right in his priorities. Cassette-tape storage of data was slow and unreliable compared to disks, and dealers were constantly complaining about it. Markkula had decided that disk drives were essential about the time he and Randy Wigginton were writing a checkbook program that Markkula thought the Apple needed. Markkula was fed up with the laborious task of reading data off cassette tapes and realized how much a floppy-disk drive would help. He told Woz that he wanted the disk drive ready for the Consumer Electronics Show that Apple was scheduled to attend in January.

Markkula knew that by issuing the edict he was in essence taking away Woz’s Christmas vacation. It was unreasonable to expect anyone to devise a functioning disk drive in a month. But this was the kind of challenge Woz thrived on. No one had to tell him to work long hours over the vacation. Woz wasn’t entirely ignorant about disk drives: while at Hewlett-Packard, he had perused a manual from Shugart, the Silicon Valley disk-drive manufacturer. Just for fun, Woz designed a circuit that would do much of what the Shugart manual said was needed to control a disk drive. Woz didn’t know how computers actually controlled drives, but his method seemed to him to be reasonably simple and clever.

When Markkula challenged Woz to put a disk drive on the Apple, Woz remembered that disk-drive circuit and began seriously considering its feasibility. He examined how other computers—including those from IBM—controlled drives. He also dissected disk drives—particularly the ones produced by North Star. After reading the North Star manual, Woz knew just how clever his design was—his circuit could do what theirs did, and more.

But Wozniak’s coming up with a circuit solved only part of the disk-control problem. The puzzle had other pieces—like how to handle synchronization. A disk drive presents tricky problems with timing. Somehow the software has to keep track of where the data is while the disk is spinning. IBM’s technique for dealing with timing involved complex circuitry, which Woz studied until he fully understood it.

All that circuitry was unnecessary, he realized, if he could alter the way in which the data were written to the disk. For the Apple disk drive, he figured out how to make the drive synchronize itself automatically with no hardware circuitry at all.

This “self-sync” technique scored a point against IBM: Woz gloated over the fact that the mammoth corporation lacked the flexibility to come up with such an unlikely solution. He also knew that no matter what economies of scale IBM brought to its product, no circuitry is less expensive than some circuitry.

Wozniak could now write the software to read from and write to the floppy disk. At this point, he called in Randy Wigginton to help. Woz needed a formatter, a program that could write a form of “nondata” to the disk, essentially wiping it clean to set it up for reuse. Woz gave Wigginton just the essential instructions, like how to make the drive motor move via software. Wigginton took it from there.

Woz and Wigginton worked day and night throughout December, including a 10-hour day on Christmas. They knew they couldn’t get a complete disk operating system running for the show, so they spent time developing a demo operating system that would let them type in single-letter filenames and read files stored in fixed locations on the disk. But when they left for the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, they weren’t even able to do that.

The Consumer Electronics Show was not a hobby computer show. Many of the exhibitors were established consumer-electronics firms that manufactured stereo equipment and calculators. The buyers of such items were general consumers, not electronics hobbyists. But Markkula wanted Apple to pursue a broader market, and he regarded this show as vital for Apple’s growth. For Woz and Wigginton, it was an adventure outside time.

Wigginton and Woz arrived in Las Vegas the evening before the event. They helped set up the booth that night and went back to work on the drive and the demo program. They planned to have it done when the show opened in the morning even if they had to go without sleep. Staying up all night is no novelty in Las Vegas, and that’s what they did, taking periodic breaks from programming to inspect the craps tables. Wigginton, 17, was elated when he won $35 at craps, but a little later back in the room, his spirits were dashed when he accidentally erased a disk they had been working on. Woz patiently helped him reconstruct all the information. They tried to take a nap at 7:30 that morning, but both were too keyed up.

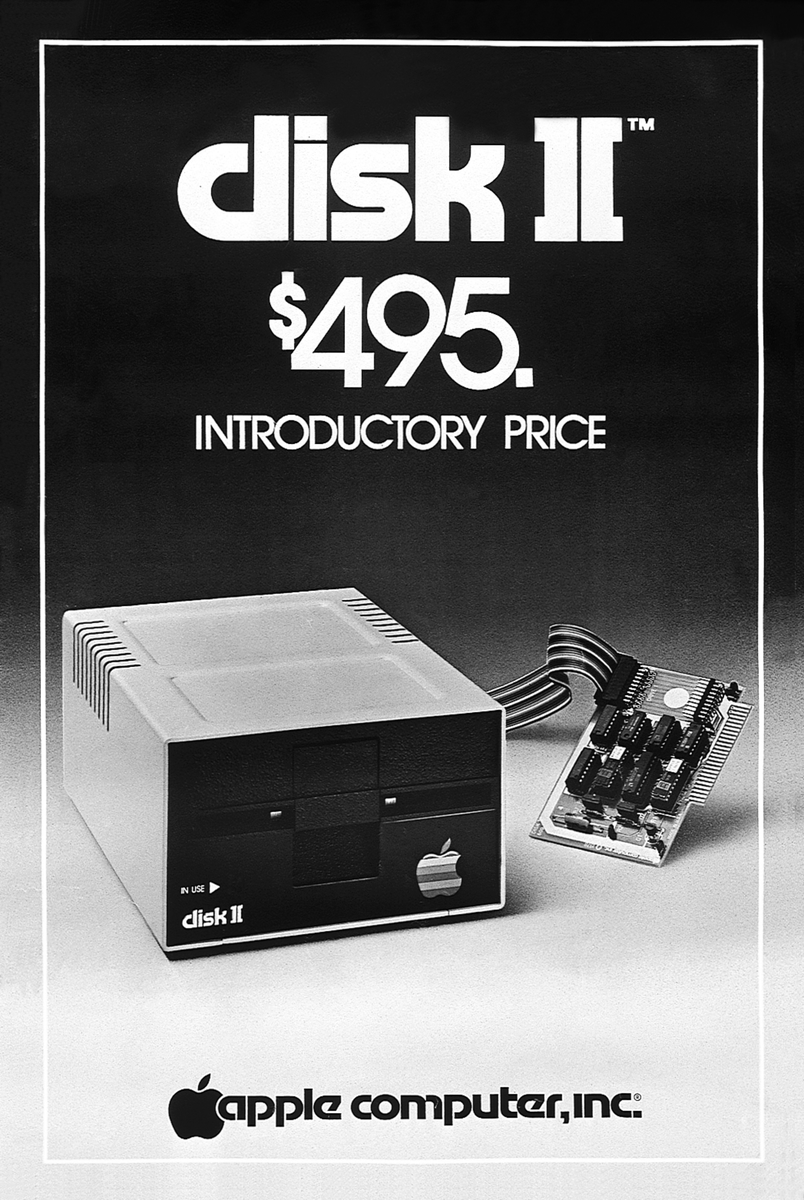

Figure 67. The disk drive Apple’s first ad as a company.

(Courtesy of Apple Computer Inc.)

Despite the snafus, the demo went well. After the show, Woz, together with Rod Holt, completed work on the disk drive so that it met Woz’s expectations as to what it could realistically accomplish. Normally the layout work was sent to a contracting firm, but the contractor was busy and Woz wasn’t. So, Woz himself laid out the circuit board that was to control the drive. He worked on it every night until 2 A.M. for two weeks.

When Woz was finished, he saw a way to cut down on feedthroughs—signal lines crossing on the board—by moving a connector. The improvement meant redoing the entire layout, but this time he completed the task in less than 24 hours. He then saw a way to eliminate one more feed-through by reversing the order of the bits of data transmitted by the board. So he laid out the board again. The final design was generally recognized as brilliant by computer engineers, and beautiful in terms of engineering aesthetics. Woz later said, “It’s something you can only do if you’re the engineer and the PC board layout person yourself. That was an artistic layout. The board has virtually no feedthroughs.”

The disk drive, which Apple began shipping in June 1978, was vital to the company’s success, second only to the computer itself in importance. The drive made possible the development of robust software like word processors and database packages. Like most early successes at Apple, it represented an enormous amount of unconstrained individual effort, as did the early achievements of the Altair and the Sol. But at Apple, the hobbyist spirit was being channeled by a few sharp executives who understood how to build a company.

The Red Book

The Apple II desperately needed a good technical reference manual. When the company started shipping the computer in 1977, the instruction manual wasn’t much better than any other documentation in the industry; that is, it was unspeakably bad. Documentation was the last thing a microcomputer company worried about in 1977. Customers were still mostly hobbyists and would tolerate abominable documentation because they welcomed the challenge of assembling and troubleshooting their machines. But Apple couldn’t afford to neglect documentation if it wanted to bring a broader spectrum of consumers into personal computing.

Apple lured Jef Raskin from a writing job at Dr. Dobb’s Journal to run the company’s documentation effort. Raskin encouraged Chris Espinosa, who had planned on attending college full time in the fall, to write something that would explain the Apple computer to its users.

The manual’s genesis is a true hobbyist’s story. Espinosa had left his high-school job at Apple to go to college and was a freshman living in the dorms at Cal Berkeley—Lee Felsenstein and Bob Marsh’s alma mater—when he began work on a manual that would explain, in a clear and organized fashion, the technical details of the Apple II. Espinosa wasn’t quite finished with it when he had to leave his dorm at the end of the term. For a week, he slept in parks and in the campus computer rooms, living out of his backpack and working 18-hour days to complete the manual. He typeset it on university equipment and turned it in to Apple.

The Red Book, as the manual came to be known, provided the kind of information that mattered to people who wanted to develop software or add-on products for the Apple II; it was a great success and unquestionably aided in Apple’s growth. It would be hard to overestimate the contribution made to Apple by outsiders and such third-party developers as Espinosa, who wasn’t employed by Apple when he wrote the Red Book.

Apple was definitely on to something, but if it was going to continue to grow, it had to get beyond enthusiasts and create a perceived need for personal computers within a broader buying public. People had to believe that the machines served a practical purpose. Gary Kildall’s CP/M operating system and the subsequent development of business-application software helped some companies sell machines in quantity. But Apple’s operating system was different from CP/M, and the Apple machines needed their own software.

Several programmers started writing games and business applications for the Apple. And although some of them were impressive, none were important enough to induce people to buy the computer just to use the program. Not until VisiCalc.

The Killer App

Back on the East Coast, Dan Bricklin, a quiet and unassuming Harvard MBA candidate, conceived an idea for a computer program to do financial forecasting. He thought it would be especially useful in real-estate transactions. Bricklin had been a software engineer with DEC and had worked on its first word-processing system. He thought he could sell his program to users of DEC minicomputers, or perhaps even sell it in the new microcomputer market.

Bricklin approached a Harvard finance professor with the idea. The professor laughed at him, but said that he might want to talk to an ex-student of his, Dan Fylstra, who had researched the market for personal-computer software. The professor also gave Bricklin the same warning he’d once given to Fylstra: because of the availability of time-sharing systems, personal-computer software would never sell.

Daniel Fylstra was a Californian who had gone east to study computers and electronics at MIT. As an associate editor for Byte magazine in its early days, he had been impressed with the chess program designed by Peter Jennings. While pursuing an MBA degree from Harvard Business School, he started a small software-marketing company, Personal Software, whose chief product was Jennings’s Microchess. By this time, Tandy Corporation had entered the microcomputer field, and the first version of the program Fylstra sold ran on the TRS-80 Model I. Fylstra liked the way graphics programming worked on the Apple II, and soon he was also offering Microchess for the Apple II.

Fylstra ended up liking Bricklin’s idea for the financial-forecasting program. The only personal computer he had available at the time was an Apple II. He lent it to Bricklin, who began designing the program with a friend of his, Bob Frankston. Something of a mathematics genius, Frankston had been involved with computers since he was 13. And he had done some programming for Fylstra’s company, converting a bridge game program to run on the Apple II.

Shortly thereafter, Bricklin and Frankston founded a company, Software Arts, and started coding the financial-analysis program. Throughout the winter, Frankston worked on the program at night in an attic office, and during the day he consulted with his partner on his progress. Occasionally the two would get together with Dan Fylstra to dream of the lucrative future that would soon be theirs.

Figure 68. Bob Frankston and Dan Bricklin They invented VisiCalc, the first electronic spreadsheet program, in 1979. (Courtesy of Dan Bricklin)

A prototype of the program was ready by the spring of 1979. Bricklin and Frankston called it VisiCalc, short for “visible calculations.” VisiCalc was a novelty in computer software. Nothing like it existed on any computer, large or small. In many ways, VisiCalc was a purely personal computer program. It kept track of tabular data, such as financial spreadsheets, using the computer’s screen like a window through which a large table of data was viewed. The “window” could slide across a table, displaying different parts of it.

The VisiCalc program simulated paper-and-pencil operations very well, but also went dramatically beyond that. Data entered in rows and columns in a table could be interrelated so that changing one value in the table caused other values to change correspondingly. This “what-if” capability made VisiCalc very appealing: one could enter budget figures, for instance, and see at once what would happen to the other values if one particular value were changed by a certain amount.

When Bricklin and Fylstra began showing the product around, not everyone responded as enthusiastically as they had expected. Fylstra recalls demonstrating VisiCalc to Apple chairman Mike Markkula, who was unimpressed and proceeded to show Fylstra his own checkbook-balancing program. But when VisiCalc was released through Personal Software in October of 1979, it was an immediate success. By this time, Fylstra had moved his company to Silicon Valley.

Another early application program for the Apple was a simple word processor called EasyWriter, a program similar to Electric Pencil, written by John Draper. Eventually Draper marketed his program through Information Unlimited Software of Berkeley, California, the same company that was selling the early database-management program WHATSIT.

But VisiCalc was far more significant.

Fylstra asked his dealers to estimate a competitive price for VisiCalc, and he was told between $35 and $100. Initially Fylstra offered the package for $100, but it sold so fast that he quickly raised the price to $150. Serious business software for personal computers was rare, and no one was sure how to price it. Plus, VisiCalc had capabilities other business software didn’t. Year after year, even as VisiCalc increased in price, the volume of sales rose dramatically. In its first release in 1979, Personal Software shipped 500 copies of VisiCalc per month. By 1981, the company was shipping 12,000 copies per month.

Not only did VisiCalc sell, but the popularity of the program also helped to sell Apple computers. It was the “killer app,” the application program that people bought the computer to get. During its first year, VisiCalc was available only for the Apple, and it provided a compelling reason to buy an Apple computer. In fact, the Apple II and VisiCalc had an impressive symbiotic relationship, and it’s difficult to say which contributed more to the other. Together they did much to legitimize both the hardware and the software industries.

Trouble in Paradise

Committee marketing decisions—that was the major source of all the problems.

—Dan Kottke

During Apple’s third fiscal year, which ended on September 30, 1979, sales of the Apple II increased to 35,100 units, more than quadruple the number of the previous year. But the company felt the need to develop another product soon. No one believed that the Apple II could remain a best-seller for much longer.

Looking for the Next Thing

In 1978, Apple took several steps to gear up for the challenge. They hired Chuck Peddle that summer, with undefined responsibilities. As the designer of both the 6502 microprocessor and the Commodore PET computer (which competed with the Apple II), he just seemed like a good person to have around. Peddle had seen possibilities in Apple even before it had emerged from the garage, and had tried unsuccessfully to get Commodore to purchase the company.

Peddle’s PET computer (said to stand for either Personal Electronic Transactor or Peddle’s Ego Trip, but actually named after the pet-rock fad of the day) was introduced at the first West Coast Computer Faire in 1977, as was the Apple II. As it turned out, the PET did not greatly influence the development of the American personal-computer industry, largely because Commodore president Jack Tramiel opted to concentrate on European sales and Commodore delayed in providing a disk drive for its computer.

Peddle and the Apple executives ultimately failed to agree on what role he would play at the company, and he returned to Commodore at the end of the year.

By that time, Tom Whitney, Woz’s old boss at Hewlett-Packard, had been hired to supervise and enlarge the engineering department in order to begin designing new products.