Data Stewardship (2014)

CHAPTER 4 Implementing Data Stewardship

To get Data Stewardship going in an organization, you need to figure out who are the key players and organizations that own data, communicate with them, and get support from their management. In addition, you must gain support from the analysts and data subject-matter experts who will provide the information about the data that will be stewarded. You must lay out the structure of the Data Stewardship Council, identify the types of Data Stewards you will need, and ascertain what information already exists in the enterprise that can provide a starting point. This information includes such things as data dictionaries, data quality specifications, and tools.

Keywords

framework; work; repository; data quality; business glossary; business function; organization; structure support

Introduction

As you begin to put together your Data Stewardship effort, there are some things you need to find out, much like surveying the land before deciding what to build on it. The first thing is to get the word out on what Data Stewardship is and find your organization champions who will help you drive it. You also need to understand how your business is organized, and ascertain who owns data and who just uses data that others own. The business functions that own data will need to supply Business Data Stewards. It is important to put together a framework that determines how the stewards work together.

Note

Data ownership means several things. First of all, it means that the owning business function is responsible for establishing the meaning (definition) and business rules (e.g., creation, usage, and data quality rules) for the data. That is, the owning business function is responsible for establishing the metadata for the data it owns. It also means that decisions about changing the metadata are the sole responsibility of the owning business function. That is, other business functions can suggest needed changes, but only the owning business function can actually make those changes. Finally, data ownership means that maintaining the quality of the data is the responsibility of the owning business function.

Beyond the organization structures though, there is the very important task of finding out what resources the enterprise has already. For example, a survey of the data analyst community might uncover a data dictionary that someone put together, a set of data quality specifications that people are using to ensure the data supports their needs, and even a set of tools in IT that can be leveraged for Data Stewardship. These tools might even be just sitting idle.

Championing and Communicating Data Stewardship

One of the most important things you need to do to ensure the success of Data Stewardship is to get the word out that it exists, what it means, and why it is important. The reasons for this are fairly simple. In a nutshell, although your stewards are highly knowledgeable about their data, no one can know everything. Especially in a large company, there are many data analysts, and some will have information the steward lacks. If the data analysts (and other data users) are aware of Data Stewardship and how it operates, as well as who the Data Stewards are, then they can:

- Bring up matters or data issues to the appropriate people. In some companies this may even mean having the data analysts open their own issues in the issue log (see Chapter 6).

- Offer solutions and known workarounds for data issues.

- Make available data dictionaries, lists of valid values, queries, data quality specifications, and other artifacts that have been useful to them.

- Advise people to contact the Data Stewardship function when the analyst believes that a Data Stewardship procedure is not being followed. A good example of a data analyst stepping in was the incident where an insurance data analyst who had sat in one of our training sessions heard that one project was planning to redefine the data element “close ratio” because they didn’t feel the current definition was accurate. That analyst advised the project lead that she needed to contact the Business Data Steward, and provided the name of that person. The Business Data Steward then worked with the group to figure out what the shortcomings were, and ended up renaming the data element to “unique quote to close ratio” and redefining it by adding more specificity to the definition. In addition, several additional data elements (e.g., “agent unique quote to close ratio”) were defined and added to the business glossary as well.

The first step in communicating and championing Data Stewardship is to be prepared to talk about it to anyone who will listen. This requires a consistent message about its value, your vision, and what Data Stewardship consists of it. The Data Stewardship message should push the ideas of metadata (definitions, derivations, creation, and usage business rules) and improvement of data quality. In addition, the message must stress that data needs knowledgeable and acknowledged decision makers. To put it another way, Data Stewardship needs three central components:

- Documented, comprehensible knowledge about data (metadata)

- Cultivation of knowledge about data for the purpose of getting more value out of data (data quality)

- A framework for making decisions about data (Data Governance)

You also need various versions of your message, from a set of sound bites all the way up to a one-hour presentation. The various-length presentations are useful under the following circumstances:

- 15 to 30 seconds: This is the classic “elevator speech,” in which you need to get your point across very quickly. You need to be prepared to tell an executive or other important person enough of what you do and why it is valuable to pique their interest. My favorite example was the day I got on the elevator with the new COO. When he asked me what I did, I managed to tell him enough (including how it would impact his favorite initiative) by the time the doors opened on the fifth floor that he asked me get on his calendar for a half hour so he could hear more (see next bullet!).

- 15 to 30 minutes: While the “elevator speech” must of necessity be delivered extemporaneously, these longer presentations are often better done with a few slides that you can leave behind. They are typically presented in executive briefings, short lunch meetings, or meetings of the direct reports to executives. For example, I was invited in to talk to the direct reports of the executive VP of insurance services to explain to these people why they should appoint resources to support Data Governance and Data Stewardship, as well as support an internal metadata/definitions project that some of their analysts wanted to do (which Data Stewardship could then leverage). I started with a brief rundown of the overall goals of Data Governance, followed by what Data Stewardship was and the importance of it, mentioning that it required assigned stewards from the business. I then finished by noting how many of their key initiatives would benefit from a strong understanding of their data, which tied directly to the metadata initiative. Sold! Of course, being able to present this information required some research into what the members of the audience considered important (the key initiatives).

- One hour and longer: Longer presentations start to move into the territory of training, presenting material at a level and depth needed by participants in the Data Stewardship and Data Governance programs. For example, a one-hour presentation on Data Stewardship should be standard delivery fare for new Data Governors so they understand the role of the Data Stewards in the overall process. Such training is critical because the Data Governors appoint the Business Data Stewards and must understand their duties and the type of person needed. “Brown bag” presentations are often close to an hour in length, and presentations given to IT developers are often up to one and a half hours long. In many companies, people who attend these presentations are given educational credit for that attendance.

Finally, you can make use of the regular communications vehicles that your company provides. These may include newsletters and various informational websites. A good communications plan (discussed at length in Chapter 6) should include all these types of communication vehicles.

Customizing the Message

One key tenet of effectively communicating anything, including Data Stewardship, is to customize your message for the audience. Customizing the message was illustrated above in the 15- to 30-minute message. Customizing the message for the audience is especially important when discussing Data Stewardship because it is often a foreign concept to many people. In addition, different audiences will have different relationships to Data Stewardship and thus different levels of detail are needed. Before talking to business people, take time to find out about the initiatives underway or being considered by that business function, and to understand how the success of such initiatives depends on data. Also pay particular attention to difficulties the business is experiencing with their data. That is, research what problems the business function has with its data, and ask what data issues have gotten in the way of their success in the past. If you focus on how Data Stewardship will help drive key initiatives or has the potential to relieve some of the data pain that they are feeling, it makes the message far more effective because it is directly relevant.

Speaking about the relationship of stewardship to their initiatives also shows that you care enough to find out about their business and don’t just deliver a canned presentation. For example, in the case of the insurance executive’s meeting discussed previously, they were struggling with various reports that showed differing results for what appeared to be the same calculated result for paid claims. I discovered (and presented) that the basic problem was that each report defined and calculated this number differently, that there was no formal accountability for either the report or the definition/calculation, and no mechanism for fixing these issues—unless, of course, they participated in the Data Stewardship effort. I pointed out that the data warehouse they were building would have the same problems unless they took the time to define and get consensus on their terms and rules. I also told them that if they implement Data Stewardship procedures, they would have a structured way to determine what dimensions and facts were needed, and ensure that all of them were defined and calculated in a consistent way, and documented in an accessible and shared repository.

Something else to keep in mind is that when presenting to IT (especially developers) there is a huge opportunity to gain an active and enthusiastic community of gatekeepers. Developers often feel the pain of being given requirements that lack the information they need to do a good job of locating and using the right data, as well as checking its validity. If you provide the developers with the tenets of doing proper Data Stewardship, they can push back when they are handed half-baked requirements and they can involve the Data Governance organization to help improve things. It is the equivalent of the “old days” when I was managing the data modeling group at a large pharmacy chain. We maintained the logical and physical models, and generated the Database Description Language (DDL) to create and modify the database structures. Of course, it was important that the database structure be in synch with the models. What we did was enlist the aid of the Database Administrators (DBAs), who were often given requests by developers to add a column here and there. This was a pain for the DBAs and caused all sorts of deployment issues. It also often led to creating columns that already existed or were created in the wrong table because the developers didn’t understand the structure of the database. The DBAs then had to undo their work. The DBAs worked with us and became the gatekeepers of the database, and would refer any request for a column to our group. We would work with the developer to understand the need, and if it was legitimate, we would change the model, generate the new DDL, and hand it off to the DBA for implementation. It was a beautiful example of teamwork, not only protecting the integrity of the database (and the models) but also getting the notoriously overworked DBAs out of the business of hand-coding DDL (the only option in those days) for these small changes.

Gaining Support from Above and Below

It is really imperative to have support for the Data Stewardship initiative from both management (above) and staff (below). The support from management should be fairly obvious—as with most efforts that span the enterprise, there will be some resistance, and management support is needed to make it clear that ignoring the effort (or worse, actively opposing it) is not okay. In addition, it usually takes clear and obvious high-level support to get employees to believe that the organization is very serious about the implementation of Data Stewardship. Further (as we will discuss in Chapter 5), Data Stewardship often involves cultural changes, and only the executives can make those happen. Finally, if the rewards system is going to be adjusted to encourage active participation in Data Stewardship, high-level management support is needed for that too.

Support from staff is less obvious but just as important. The ideal situation is to build a ground swell of support in the organization, and that requires winning the hearts and minds of the analysts who use the data and feel the pain. That pain—which stems from the lack of definitions and standardized derivations, poor or uncertain data quality, and no guidance or rules for creation and usage of the data—serves as incentive to the analyst community to participate and support the Data Stewards. Much like the developers, the data analysts can be your eyes and ears throughout the organization, and can bring data-related issues to the Business Data Stewards for a solution. The data analysts directly benefit from better-defined data, better-quality data, and data with rigorous rules about creation and usage. Make them aware of this benefit and they will be your allies. Fail to do so, and they can end up looking on the Data Stewardship efforts as more overhead and a roadblock to getting their work done.

Support from below can provide you with champions of Data Stewardship throughout the organization. These champions will help you get out your messages of success. If the data analysts are happy with the improvements in data quality and how the data is used, they trumpet those successes. That is, they tell their colleagues how these new techniques deliver value and recommend that the Data Stewards be engaged whenever there are data issues, including uncertain meaning and poor quality.

Practical Advice

If you’re good at getting out the message about the value of Data Stewardship and how important it is for the data analysts to participate and support it, you may find yourself in the position of “overwhelming demand,” with many analysts bringing multiple issues to you to be dealt with. This situation can develop rapidly in organizations with a lot of data problems. At first glance, having people bring a multitude of data problems to the Data Stewards might appear to be a good thing, but that is not necessarily true. If the Data Stewardship effort is overwhelmed, and there starts to be long delays in dealing with issues that are brought up by the analysts, the analysts may get frustrated and stop participating because they don’t see any results. What to do? The first thing is to have the Business Data Stewards prioritize the issues. That usually involves having the Data Stewards talk to the analysts who raised the issue in the first place to determine the impact that the issue is having on the analyst’s work and the analyst’s understanding of the scope and work effort needed to resolve the issue. The Data Stewards may also recruit an analyst’s help in getting the issues resolved.

Understanding the Organization

Organizations have a structure, which is often represented as an organization chart. They also have a culture that affects how decisions are made. It is imperative that you have a good understanding of both of these facets of an organization to set up and run an effective Data Stewardship organization.

Organization Structure

Since Data Governance and Data Stewardship are all about caring for the data and making and enforcing decisions about the data, it is critical to understand which business functions own data, and what data they own. It is also important to understand how the organization makes decisions and what levels of the organization make those decisions. Understanding the organization’s levels is critical so that participants in Data Governance (e.g., members of the Executive Steering Committee, Data Governance Board, and Data Stewardship Council) can be selected from the right decision-making levels.

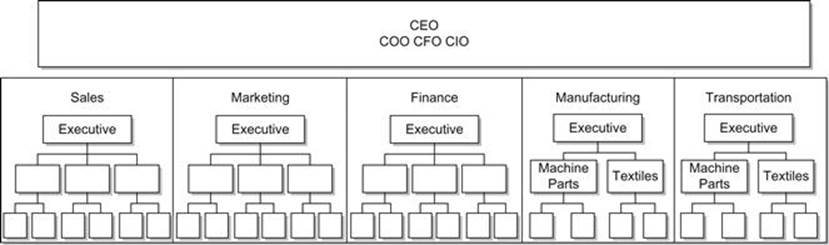

The first step in sorting out the organization’s decision-making levels is to understand how the organization is structured. The structure can be relatively straightforward, as illustrated in Figure 4.1.

FIGURE 4.1 A fairly straightforward organization chart.

The complexity of the organization chart is not necessarily a function of the size of the company. Instead, it tends to vary by the number of business lines the company is in, though size often correlates with a large number of lines of business, and how many layers of management the organization has in place.

When building up a Data Stewardship function, however, you need to look past the strict structure of the business units and focus on the business functions. How do business units differ from business functions? A business unit is a structural part of the organization—that is, a division or a department in the overall company. A business unit often has its own budget and management structure as well. On the other hand, a business function is an area of the business responsible for the execution of a particular set of business responsibilities. On the face of it, they may sound the same, but they are not. Business units change frequently, that is what reorganizations are all about. I worked in one company that had a membership department and an insurance department. In less than a year, the two departments were bundled together into a “product” department, and then broken apart again. This kind of fluidity can play havoc with the assignment of Data Stewards if based on the business units—each restructuring may change the makeup of the Data Stewardship Council. On the other hand, business functions rarely change unless the basic nature of the business changes (the company gets into a new business area it had not been in before). If you base the Data Stewards on business function, they don’t have to change even when reorganization occurs. That is, basing the Data Stewards on business function rather than business unit makes Data Stewardship more stable. For example, the membership and insurance Data Stewards did not change as a result of the aforementioned reshuffling of the company’s departments.

Focusing on business functions means that restructuring is largely irrelevant. For example, if the transportation department for textiles was suddenly reorganized to be under manufacturing for textiles, the transportation steward wouldn’t change because the transportation business (and data) didn’t change.

Basing stewardship on business function also provides more flexibility. For example, Figure 4.1 shows a company that has two main lines of business: manufacturing machine parts and textiles. While the data around these business areas is likely to be quite different, notice that the company also has a transportation division that is also split into departments for machine parts and textiles. But warehouses are warehouses, and trucks are trucks, so the data there is likely to be quite similar and the company could benefit from having common definitions and quality requirements across the two departments.

Practical Advice

Even complex organizations tend to have fairly standardized functions, such as finance, sales, and marketing. These are good places to start a Data Stewardship effort. First of all, sales and marketing are often able to quantify the pain they suffer from poor data. For example, a large insurance company marketing organization paid out $24,000 each month to an outside firm to standardize addresses and recognize when two of pieces of mail were going to the same person (no customer Master Data Management existed). In addition, a sample count revealed that they also paid out about $3,000 per month mailing to outdated addresses.

The Business and Technical Data Stewards for this data worked together to:

- Add enforcement at data collection to allow only valid addresses

- Purchase outside data on valid addresses

- Do address standardization on existing addresses

The result was that in just five months of eliminating these costs, the company had earned back the money that had been invested in improving the data.

Finance is another good place to start because the finance department not only has standardized definitions and calculations for external reporting, but is also used to having rigorous governance of its data. The financial analysts often have the authority to force the reporting agencies to standardize and improve the data being reported. Rigorous governance is such an integral part of finance, that in many organizations the Data Governance function may fall under the CFO.

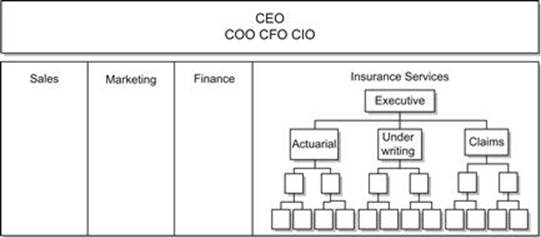

As shown in Figure 4.2, a single division may have multiple Data Stewards as well. A large and complex business area (e.g., insurance services) may handle several categories of data (e.g., actuarial, underwriting, and claims) and often requires one or more stewards from each because no one person is familiar with all three sets of this widely disparate data. Again, the point is that the organization chart is not a straitjacket when it comes to Data Stewardship, and is often not the best way to designate stewards.

FIGURE 4.2 A single business function may have multiple stewards, such as this example for an insurance company.

Note

In theory, a Business Data Steward can come from any level of the organization, as they are designated as having the authority as well as roles and responsibilities detailed earlier in this book. But it doesn’t hurt if Business Data Stewards are chosen from the ranks of people who already have some decision-making authority, as long as those people meet the requirements for being an effective Business Data Steward. Thus, there is a balance between someone who knows a lot about the data (because of his or her experience regardless of whom he or she reports to) and someone who has direct power to make decisions because of whom he or she reports to.

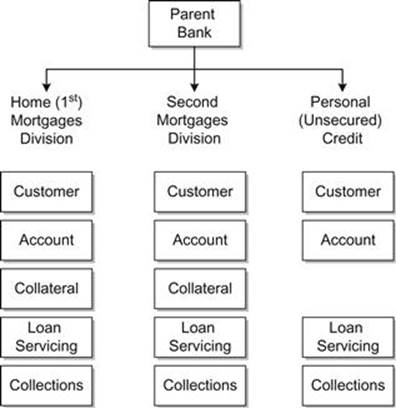

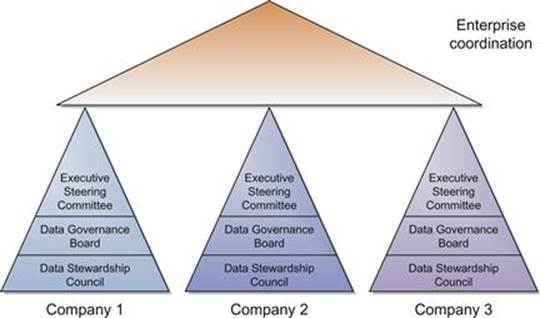

Things start getting more complicated when an organization is highly complex, or has the same function occurring in multiple subsidiaries, as shown in Figure 4.3. An organizational structure like this can often grow out of a vigorous growth-by-acquisition strategy. When this kind of organizational structure exists, it invites different business units to adopt different definitions and business rules. In such cases, it is even more critical to have Business Data Stewards, maybe even having one steward from each business unit to ensure that consistency is enforced where it is likely to be beneficial.

FIGURE 4.3 An organizational chart where very similar or identical business functions take place in different subsidiaries, leading to data overlap.

For example, a large bank grew by acquiring other banks, and keeping systems and business functions that were superior to the existing systems and functions. This did, however, lead to the odd situation where first mortgages were issued from one subsidiary (and system), second mortgages were issued from another, and personal credit (which has no collateral) was issued by a third. As you can probably imagine, the vast majority of data used by the three systems was (or should have been) the same, yet issuing a combined first and second mortgage was next to impossible. Each business function felt that it owned the data it used, and the only way to resolve this was by joint ownership, with the three Data Stewards working closely together to reach a consensus on meaning and business rules. A side benefit of this arrangement was that the three stewards were able to determine in which system the data was of better quality and match customer/account holders across the systems. This was possible because in a banking environment, the SSN (Social Security Number) was a valid identifier for the account holders and was always (well, almost always) collected when the account was opened.

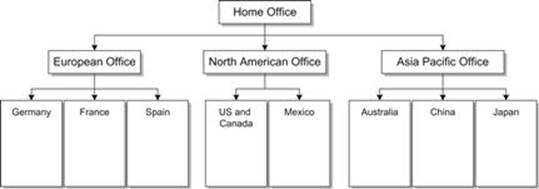

Establishing Data Stewardship gets even more complicated when the company is divided up by country, each with different regulations, languages, and customs. A sample of such an organizational structure is shown in Figure 4.4.

FIGURE 4.4 A more complex organizational chart for a multinational corporation.

The typical implementation in a situation where each company operates with a great deal of autonomy is that each company has to establish its own Data Governance and Data Stewardship, pretty much independent of the other companies. Once this occurs, an international board then needs to look across the key data elements and focus on those for which there is a solid business reason to have a common definition and business rules across the entire company. To achieve the goal of having commonality across key business data elements, it may be necessary to modify the metadata (e.g., the definition) in each company to match the definition required at the corporate level. Another solution may be to define the set of common data elements and a derivation rule from each company’s data to the common data. A Data Stewardship organization to support largely autonomous companies is shown in Figure 4.5

FIGURE 4.5 Data Stewardship for a multinational company usually must add the enterprise layer to handle the common business data elements.

Culture of an Organization

It is important to understand the organizational culture if you want to be successful at implementing a Data Stewardship program because Data Stewardship almost always requires significant cultural change. This is especially true if you have been hired from outside the organization to implement Data Stewardship. The rigorous establishment of decision rights for data is often a new experience for the organization as a whole, as well as for those who use the data. So is establishing and enforcing processes for dealing with data issues. The analysts may be used to having endless discussions to reach consensus, or simply doing what they please with the data. Data Stewardship changes all that, so people have to do things and behave differently than they used to. It may be quite a shock for the analysts to discover that the Business Data Stewards have the authority to state what the data owned by the steward’s business function means, how it is calculated, and what the quality, creation, and usage business rules are with little discussion. That is, the concept of data decision making may be foreign to the corporate culture, and that has to change. Changed behavior has cultural impacts. This is especially true in companies where achieving consensus is a requirement for every decision. While Data Stewards should try to get people to work together, understand data in similar ways, and achieve consensus, in the end they are responsible for getting recommendations (and ultimately decisions) made, whether consensus is achieved or not.

Of course, you aren’t going to be able to change the culture right away, nor would you want to, as you need to understand the current state before trying to make changes. Analyzing the current culture really helps to understand where there will be issues. In companies where decision making by designated individuals (who may be peers of the people they are making decisions for) is inconsistent with the company’s culture, executive support is even more important. The company’s leaders must put out the message that this new way of doing the “business of data” is accepted and supported by upper management, and is in the best interests of the enterprise. This same message must be repeated by the Data Stewards and the Data Stewardship function of the Data Governance Program Office (DGPO) whenever there is pushback from people in the organization.

Organizing Data Stewards

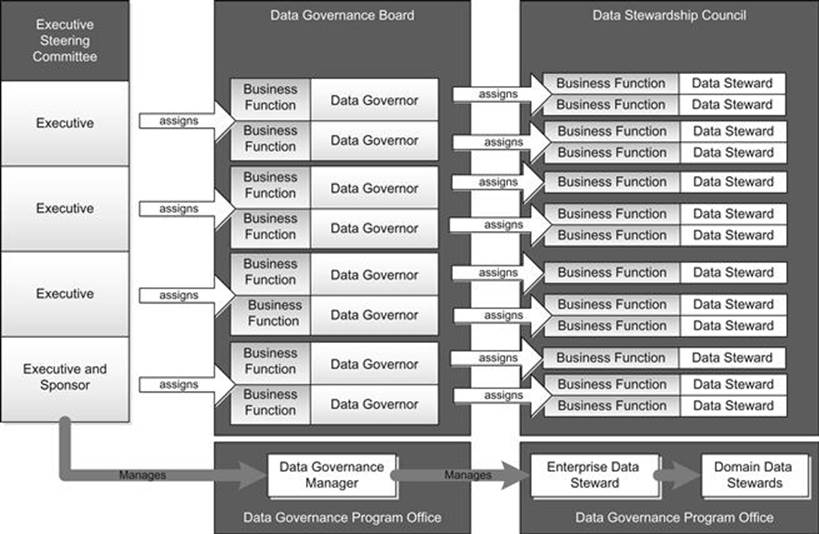

As discussed in Chapter 1, Data Stewards are organized into a Data Stewardship Council, which works with the Data Governance Board and subject-matter experts to make decisions about data. Figure 4.6 shows the relationship between the various groups involved in Data Governance (including the Data Stewards). The DGPO is shown across the bottom. Notice that the members of the DGPO are recommended to be part of the business (rather than IT), and to report to a business executive (whoever the sponsor is).

FIGURE 4.6 The interaction between the various levels of the Data Governance participants and organization.

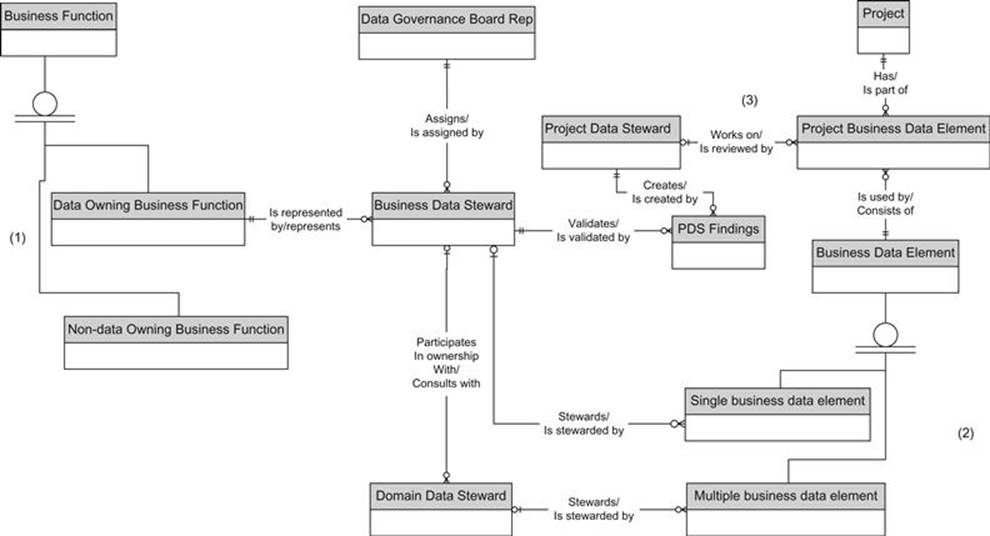

The various types of Data Stewards (Business Data Stewards, Domain Data Stewards, and Project Data Stewards) also need to be organized to work together smoothly, so it is important to understand the relationships between the stewards and what they deliver.Figure 4.7 shows a conceptual model that illustrates these relationships. We will discuss that next.

FIGURE 4.7 A model of how Data Stewards work together.

Here are some key points illustrated by the model shown in Figure 4.7:

- Business functions can be broken up into two subtypes: those that own data and those that don’t (1). There are a significant number of business functions that don’t own data, such as corporate audit, who just make trouble for everyone else by examining the data, but don’t have any of their own. Of course, the really interesting part of the Data Stewardship model hangs off the data-owning business functions.

- Business data elements can be broken up into two subtypes: those that can be stewarded by a single business function and those that must be jointly owned by multiple business functions (2). The multiple business function data elements are stewarded by a Domain Data Steward, who works with the multiple interested Business Data Stewards.

- A data-owning business function is represented by a Business Data Steward, who is assigned by a representative from the Data Governance Board. The Business Data Steward is responsible for stewarding single business function data elements—that is, business data elements that can be owned by a single business function.

- Projects have or define business data elements, which are shepherded along by the Project Data Steward (PDS) (3). The Project Data Steward is in place to make sure people understand the meaning of the data and can assess it. The Project Data Steward does not directly make decisions about the data, but works with the designated Business Data Steward to get decisions, definitions, and business rules determined for the project and the enterprise.

As you can see, the various Data Stewards need to work together, especially when there are large projects underway. Working together usually means periodically meeting to

- Determine ownership for new data elements

- Coordinate the work between the Business Data Stewards and Project Data Stewards

- Determine interested parties for shared data domains

- Prioritize new data elements to be brought under Data Governance

These meetings, as well as other ways of coordinating work, are discussed in Chapter 6. But it is important to note that you don’t necessarily have a meeting every time an issue comes up—there are better and more efficient ways to handle the coordination between stewards, such as email-driven issue lists.

Figuring Out Your Starting Point

As you kick off a Data Stewardship effort, you are going to be focusing on data, metadata, improving data quality, clear and repeatable processes, and implementing a robust toolset for documentation and information. The good news is that you rarely have to start from scratch; the chances are that someone somewhere has been collecting this sort of information, perhaps for their own use, perhaps to help out the group they belong to. If you can locate this information, you’ll have a body of work to build from.

Figuring Out What You’ve Got: The Data

To govern and steward your data, you are going to have to know about the following items:

- What data you have. Initially, this information will be more in terms of data domains (e.g., finance, sales, customer, product, and so on) than specific data elements. And while it is likely that stewardship will eventually be assigned at the individual data element level, it is still very useful to have an idea of what domains of data are important to your enterprise. You can think about data stewardship at a macro level, and associate business functions with data domains, as shown previously in Figure 2.3. This serves at an excellent starting point for the more granular approach of stewardship at the data element level, as shown previously in Figure 2.4.

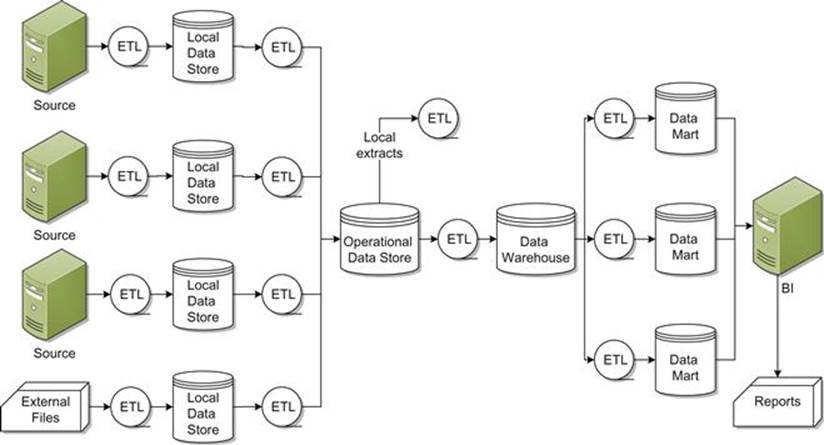

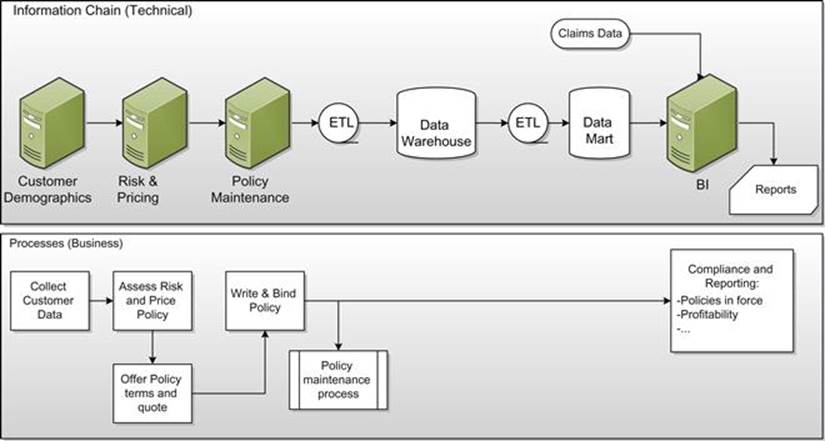

- Where the data comes from. Data doesn’t just sit in one place, it flows through the enterprise. This flow, known as the information chain, includes capture (via outside files or source systems), movement and transformation (via Extract, Transform, and load, or ETL), storage (in intermediate databases and operational data stores), summary and aggregation (in data warehouses and data marts), and being used for decision aking (via business intelligence). Of course, there is not just one information chain in an enterprise, and the chains may branch off in varied (and often strange) ways. A simple information chain is shown in Figure 4.8.

FIGURE 4.8 Information flows through an enterprise in the information chain.

- What parts of the organization are responsible for source data capture, ETL, and reporting? Typically, various IT groups are responsible for “chunks” of the information chain, including the source systems, ETL, data stores, and business intelligence reporting environments. These groups (along with enterprise architecture) can help you figure out how the data flows, what occurs in the various source systems, where files are consumed or produced for outside sources, and the key reports produced (which will help you understand what data is most important to the organization). Knowing who these folks are and establishing a good working relationship with them will go a long way toward understanding the data and how it is used.

Business Processes and the Information Chain

The information chain is in place to support the flow of business data for business processes. Understanding these business processes is important to making sense of the technical systems and processes in the information chain because the technical systems and processes support the business processes. That is, without the business processes, there is no reason to even have the information chain. When analyzing the purpose and details of an information chain, the first step is to understand the business process it supports. Oftentimes, information chains linger long after the business process has changed or been discontinued; if that happens, the information chain needs to be modified or eliminated altogether.

An example of the relationship between the information chain and business processes may help. Figure 4.9 shows an information chain (in the top box) and the business processes supported by the information chain (in the bottom box). This example, which is based on writing an insurance policy, shows how the processes necessary to assess the risk, offer a policy, sell (“bind”) the policy, and report on what has been accomplished line up to the various systems and infrastructure (e.g., the data warehouse and data marts) support the needs of the business. Note also how the business process flow may (and usually does) branch off to other business processes (e.g., the policy maintenance process), which are themselves supported by an information chain.

FIGURE 4.9 An information chain exists to support business processes.

Practical Advice

In an enterprise of any complexity, you are not going to get all the information related to the flow of data through the organization at once. However, you can focus on the data and information chain for major areas of the business on a one-by-one basis, and come up to speed incrementally. The priority of digging into the available data will often be dictated by high-visibility projects and issues. Also, don’t forget that enterprise architecture often maintains diagrams that illustrate various information chains and how they interact. Enterprise architecture may also be able to provide a good high-level schematic of the enterprise as a whole, which is crucial before starting on any given piece of the overall information chain.

Figuring Out What You’ve Got: The Metadata

Metadata is key to a Data Stewardship effort. Much of what you need to discover and document about your data is its metadata. The chances are good (because metadata is so useful to the analysts making use of the data) that those same analysts have collected what they need in various ways, and documented the metadata in everything from home-built desktop databases to spreadsheets. The key is to find the metadata, collect it, and validate it with the Business Data Stewards.

Note

Once Data Stewards have been designated, a significant portion of their job is to create and manage metadata. When new sources of metadata are discovered (e.g., another analyst offers a spreadsheet of definitions), they should be referred to the appropriate Data Stewards.

Definition

And what is metadata? In her book Measuring Data Quality for Ongoing Improvement (Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2013), Laura Sebastian Coleman defines metadata: Metadata is usually defined as “data about data” but it would be better defined as explicit knowledge, documented to enable a common understanding of an organization’s data, including what the data is intended to represent (definition of terms and business rules), how it effects this representation (data definition, system design, system processes), the limits of that representation (what it does not represent), what happens to it as it moves through processes and systems (provenance, lineage, information chain, and information life cycle), how data is used and can be used, and how it should not be used.

The important parts of digging up the metadata include:

- Finding definitions. Many analysts collect data definitions. They usually also collect lists of valid values and their meanings, so that they can evaluate and use the data that consists of code values. Report writers/managers are a good source of data definitions. This is because people who receive the reports usually turn to the reporting folks whenever they don’t understand what they are looking at in the report or think some result looks “off.” Although the people who construct the reports are often initially not experts on what the data means, they begin collecting and documenting this information in self-defense so that they can answer the questions that invariably come their way. People who input the data may also understand the data definitions, and in fact, this is the ideal case. If the people who perform data input understand what they are inputting, they are often the first to become aware that something is not right with the data.

- Finding derivations. Analysts also collect data derivations, which are rules about how a quantity is calculated or otherwise derived. These rules are often embedded in program code, and thus require a different kind of research and documentation than definitions.

- Where is the metadata being kept? Most of the people who collect metadata for their own uses store it away in spreadsheets or something similar. Gathering up copies of these, keeping up with the latest versions as they get updated, and cross-indexing between multiple spreadsheets to locate the duplicates can be a painful task. Ideally, you’ll want to convince the providers of the metadata to start using a shareable resource (such as a SharePoint-based glossary) and updating that resource via a set of procedures designed to protect the integrity of the metadata. This would eliminate most of the “housekeeping” in keeping up to date as the metadata changes in all the various little repositories. The ideal situation is that metadata is kept in a single, enterprise-wide repository, the use of which is enforced by the DGPO.

- Is anyone managing and validating the metadata and by what means? It is often true that the people who are collecting metadata for their own purposes simply jot it down in a spreadsheet (or some other tool). But groups of analysts may discuss and validate the metadata, perhaps to create a single consolidated list of data elements with definitions for their department. The validation effort usually consists of reaching a consensus, or perhaps asking the person who they all agree is the best expert on the data (sounds sort of like a Data Steward, doesn’t it?).

Note

There are many different kinds of metadata, so “validation” of the metadata can take many different forms. Some metadata is fairly easy to validate—database structures can be validated by examining the database itself. Business metadata (i.e., data names, definitions, derivations, business rules) must be validated by working through agreed-on processes with the Business Data Stewards (including ascertaining what business function owns the data).

![]() In the Real World

In the Real World

At one large bank where I worked, the data analysts across the company could dial into a weekly meeting where data and metadata were discussed. The discussions revolved primarily around what data was available, what it meant, how it was derived, what issues were known, and where it was stored. They could send in questions, and the attendees would provide input and answers. The Enterprise Data Steward attended these meetings and would collect this intelligence, then work with the appropriate Business Data Stewards to find answers, validate the provided information, and get the metadata into the repository.

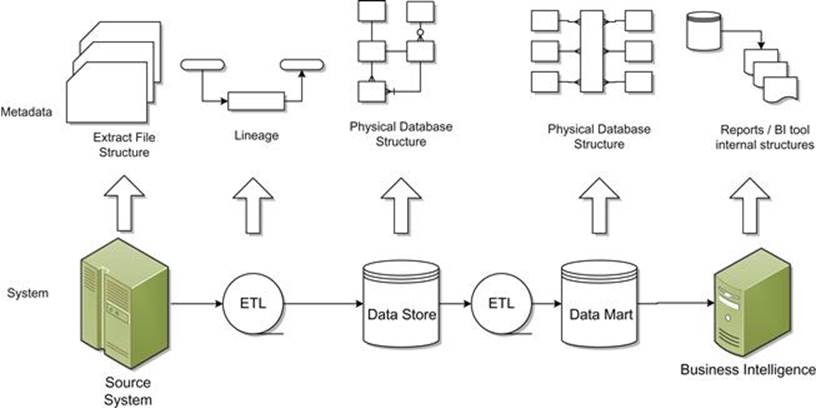

- How is IT tracking its metadata? Many of the tools that IT uses, including ETL and data profiling tools, produce a considerable amount of metadata. In general, these tools store the metadata internally in some sort of repository. Most modern tools support extracting this metadata into another tool (e.g., a metadata repository) for use (see Figure 4.10). More advanced IT departments may indeed go this extra step to make the lineage, data profiling results, and physical database structures available even to those who don’t use these tools. But even if your IT department doesn’t externalize the metadata, just knowing what tools they use for these purposes will make it more straightforward to get at metadata that is important to use in the Data Stewardship effort.

FIGURE 4.10 Extracting metadata from IT data tools makes it available to a much wider audience.

- Are there any data dictionaries for legacy systems lying around? One of the toughest nuts to crack is to understand the meaning and usage of data in older systems. These systems often form the backbone of corporate processing, but just as often the people who understood them have long since retired or moved on. Any documentation you can find, even if it is out of date, can help with the understanding of the data captured, used, and stored in these systems. Data dictionaries from older systems often reside in printed binders, stashed away on some dusty shelf, so it may be a bit of treasure hunt to locate them. Generally, though, it is worth the effort!

- Does the current project methodology support capture and validation of metadata? Capturing and validating metadata as part of a project is absolutely critical. Even if you can’t find metadata from older systems, ensuring that you capture the metadata as part of projects can start to make up for the lack of documentation. Projects often expose new data to scrutiny, questioning meaning, attempting to ascertain whether the data actually represents what the documentation says it does, and examining the quality of the data to ensure that it can be used for the project’s needs. As these investigations proceed, a lot of important metadata is discovered. If the project methodology demands that the metadata be captured and validated, then project documents become an important source of metadata. Ideally, the project methodology would capture this information in an easily available form, rather than some Word document that gets stuffed into a set of files or printed and put on a shelf. Unfortunately, this level of sophistication is rare in companies that have not already implemented Data Stewardship.

Note

One of the most important jobs for the DGPO is to establish the deliverables around metadata and data quality for projects by working with the Project Management Office. Establishing the deliverables includes at what stage of the project the deliverables must be completed, sign-off authority, and how the deliverables are to be leveraged for future use through various web-based tools. In addition, the project managers must be trained to include the deliverables and budget in their project plans, and call on Data Governance to provide resources to represent the interests of Data Governance on the project (Project Data Stewards).

Figuring Out What You’ve Got: Data Quality

Improvement of data quality is not only a very important goal of Data Stewardship and Data Governance as a whole, but one of the more important ways of measuring how successful your stewardship effort is. Improving the quality of data so that it becomes more useful and presents less risk to the enterprise can reap huge benefits. One of my favorite stories is from Con-Agra, the huge food (among other things) company. Most shipment is done by loading product onto pallets, and then loading those pallets onto trucks. Not surprisingly, the size of the products determined how much product could be loaded onto a pallet. However, the product size data was of poor quality, which led to the suspicion (as well as the observation) that trucks were not leaving fully loaded. Improving the quality of product size data (by actually measuring and recording the product dimensions) allowed for more efficient loading of product onto pallets, enabling 19 trucks to do the work that required 20 trucks previously. That is, every 20th truck was essentially free, resulting in a 5% reduction in cost. The cost savings benefit dwarfed the cost of improving the data quality.

Since improving data quality is so important, it is one of the early tasks that the Data Stewards will want to focus on. It is usually not too hard to convince them of this priority, as they live with the pain of poor data quality on a daily basis. This includes hunting down data that is of sufficient quality, extracting and “correcting” data to get it up to the required level of quality, or simply not being able to produce deliverables required. Very often a good starting point for working on data quality in Data Stewardship is to find out why analysts are extracting data into their own computers from source systems or official data stores. Very often the reason is to manipulate the data in ways they have deemed necessary to get the quality up to snuff.

To get started on the data quality aspects of Data Stewardship, you need to ask the following questions:

- What data quality issues have been raised and documented? Data quality issues give a very real sense of where the pain points are in the data picture of the enterprise. Of course, just because someone classified an issue as a data quality issue doesn’t mean that the Business Data Stewards need to be involved in correcting the issue. For example, I once saw a data quality issue raised because an entire table was empty. And while a big batch of missing data is a data quality issue, in fact, the cause was that a job didn’t run correctly, and IT needed to correct it. So use a trained eye as you look at data quality issues. Once you sift out the issues that are clearly technical (job didn’t run, table space was too small, column was missing) you should have content-related issues remaining that need to be addressed by the Data Stewards. You can then categorize these and start examining how often they occur, along with input from the Data Stewards on root causes and impacts to the business. There are a variety of places where a data quality issue could be documented, so you’ll need to know where to look. Possibilities include:

![]() A real data quality issue log. This is rare unless Data Governance has been implemented and procedures are in place to collect data quality issues and put them only in the log.

A real data quality issue log. This is rare unless Data Governance has been implemented and procedures are in place to collect data quality issues and put them only in the log.

![]() The IT issue-tracking tool, sometimes called trouble tickets. Data quality issues end up here a lot when there is nowhere else to record them. Unfortunately, these issues often get lost among the wealth of purely technical issues. In addition, IT often then gets forced into taking responsibility for fixing issues that should belong to the business and require business input.

The IT issue-tracking tool, sometimes called trouble tickets. Data quality issues end up here a lot when there is nowhere else to record them. Unfortunately, these issues often get lost among the wealth of purely technical issues. In addition, IT often then gets forced into taking responsibility for fixing issues that should belong to the business and require business input.

![]() The Quality Assurance (QA) issue-tracking tool. Data quality issues can come up as new discoveries during QA testing of systems. This is especially true if test cases have been written around the data and what data is expected to be returned. Further, the more competent QA tools can be customized to provide an ideal environment to record data quality issues and track progress and workflow in finding and implementing a solution.

The Quality Assurance (QA) issue-tracking tool. Data quality issues can come up as new discoveries during QA testing of systems. This is especially true if test cases have been written around the data and what data is expected to be returned. Further, the more competent QA tools can be customized to provide an ideal environment to record data quality issues and track progress and workflow in finding and implementing a solution.

![]() Project documentation. If data quality issues come up as part of a project, they may be recorded in the project documentation. On occasion, projects may be tabled or cancelled because the quality of the data is so bad that it simply can’t be used for the project’s purposes. This may lead to a whole new project to fix the poor-quality data.

Project documentation. If data quality issues come up as part of a project, they may be recorded in the project documentation. On occasion, projects may be tabled or cancelled because the quality of the data is so bad that it simply can’t be used for the project’s purposes. This may lead to a whole new project to fix the poor-quality data.

- Are there any projects “in flight” to fix data quality issues? If poor data quality is making it difficult or impossible for the company to do business the way it wants to, one or more projects may have been initiated to correct the data quality issues. It is very important to locate these projects early in the Data Stewardship effort. The benefit of engaging Data Stewardship on data quality improvement projects is very high. These projects also point directly at data quality issues that are so important (and so high profile) that the company is willing to spend significant amounts of money on them. Helping to enable these projects shows a clear and rapid return on investment for the Data Stewardship effort and leads to buy-in from people who might otherwise ignore the effort. In addition, engaging Data Stewardship can help prevent the same data quality issues from occurring again.

- Does the current project development methodology support capture of data quality rules? As mentioned previously, projects often expose new data (and old data) to scrutiny, examining the quality of the data to ensure that it can be used to meet the project’s goals. As the projects progress, a lot of information about data quality (and lack thereof) is discovered. If the project methodology demands that the data quality rules be captured, validated, and compared to the data, then project documents become an important source of data quality rules. Again, ideally, the project methodology would engage Data Stewardship in discovering and defining data quality rules; these rules would then be documented by the Data Stewards.

- Is anyone doing data profiling? Data profiling consists of examining the contents of a database and providing the findings in a human-readable form. Most data profiling is done using tools designed specifically for that purpose. The tools are quite sophisticated, and can discern possible data quality rules from the data, as well as point out the outliers. For example, the tools might ascertain that a particular column contains only positive numbers formatted as money, or that the contents of a column are unique with just a few exceptions. Most profiling tools also enable you to enter specified data quality rules (e.g., “the contents of this column must never be null”) and then tell you how often that rule is violated. The point of data profiling is to try and spot data quality issues proactively and analyze those issues. Data profiling requires an environment. In addition, there is considerable expense for the tool and efforts by both the Business Data Stewards and Technical Data Stewards to analyze the results. Thus, it is not something that is done on a whim. If you discover that data is being profiled, it is likely to be important data for which data quality issues are a significant problem. This would therefore be a great place to focus a Data Steward’s data quality improvement efforts.

Figure Out What You’ve Got: Processes

Data Stewardship establishes and enforces repeatable processes for managing data. However, even in the absence of a Data Stewardship program, organizations often have already established processes. Finding, documenting, and possibly formalizing these processes—and the business reasons for the processes—can give a Data Stewardship program a jumpstart. For example, one company has to report its data to a state agency. To avoid having the data rejected by the state agency (which could affect funding for many programs run by the company), the company instituted a set of over 100 data validation checks on the load to the data warehouse. The company established a set of processes for specifying, creating, and testing new data validation checks, as well as a robust set of business processes (including accountable personnel) for remediating errors that were reported by the checks. The business processes include analyzing the errors to identify the source and root cause, working with the users of the source system to correct the data, training the users to prevent future occurrences, and tracking the number and distribution of the data errors. As you can see, this process could easily be leveraged by Data Stewardship, and the accountable personnel could even be considered either Business or Operational Data Stewards.

Figure Out What You’ve Got: Tools

A full-fledged Data Stewardship effort benefits significantly from a robust toolset. Tools include a metadata repository (with a business glossary component), a data profiling tool, and some sort of collaboration/website tool to post issues, handle communications, and so on. Of course, licensing all these tools could be quite expensive, and many Data Stewardship efforts have little or no budget when they first get started.

Before you throw up your hands in despair, talk to the IT people, especially those responsible for software licensing. It is possible that you already have some or all of these tools and don’t even realize it. For example, at one company where I worked, we had licensed the entire tool suite from a prominent vendor known for their ETL tools. However, it turned out that the suite also included a data profiling tool, a business glossary tool, and even a metadata repository. None of these tools were “best in breed,” but we could start using them without any added expense, and some of them were even in production and sitting unused.

Many companies also have Microsoft SharePoint or its equivalent, and use this type of tool to create department websites. Data Stewardship can do the very same thing, again, for little or no cost. It does require a certain amount of expertise to use SharePoint (or its equivalent) effectively, but such expertise usually exists in the company if the tool is widely used. We even used a SharePoint list as our starting business glossary. Again, it wasn’t the ideal solution due to the limits of the tool, but it was better than a shared spreadsheet!

Another important tool is some variation on a data quality dashboard to show what is being worked on and the level of quality in various data quality dimensions such as timeliness, validity, integrity, completeness, and others. While it is possible to cobble together something out of a spreadsheet and a whole bunch of macros, if you already have a business intelligence tool (all of which can generate dashboard-style reports), you can feed the results from data profiling into the business intelligence tool and generate dashboards.

Summary

There are many steps to getting Data Stewardship going. Understanding your organization and its culture, getting the message out and gaining support, and surveying what resources exist are all tasks you need to undertake at the beginning. But performing them gives you a clear baseline for your efforts, from which progress can be measured.