Data Stewardship (2014)

CHAPTER 6 Practical Data Stewardship

Tools, processes, key business data elements, an issue log, and metadata are discussed as cornerstones of practicing practical Data Stewardship. The importance of a communications plan for disseminating decisions to the enterprise is also discussed.

Keywords

issue log; workflow; business metadata; Wiki; business glossary; metadata repository; repeatable; processes; logistics; work groups; communications

Introduction

If done properly, Business Data Stewardship achieves its goals, providing job satisfaction and a sense of adding value to the participants. They work together as a team, see the results of their efforts, and end up doing less—but more effective—work. If not done properly, Business Data Stewardship can overwhelm the stewards, leading to frustration and “push back” from them. The key is to focus on just the practical and fundamental aspects of Data Stewardship: determining the key business data elements and assigning stewardship for them, creating quality metadata (e.g., a business definition and business rules), creating and following a set of repeatable processes, and putting procedures in place to streamline the logistics of working together.

The day-to-day stewardship work often revolves around issues that have been raised and must be dealt with. A well-managed issue log can provide structure to this work and ensure that the issues are resolved in a timely manner. Other tools, such as a Data Stewardship web portal, Wiki, business glossary, and metadata repository, can guide the stewardship work, and ensure that decisions are documented and published to the enterprise. Key to the documentation and publication of decisions is a Data Stewardship communications plan, which should leverage common enterprise communications (web articles, newsletters, and brown-bag presentations), as well as create specialized Data Stewardship communications for participants in the effort.

The Basics

The starting point for Data Stewardship is to choose the key business data elements that are worth spending time on, and creating robust definitions, derivations and business rules for creation and usage. Of course, to do all this, you need to assign a Business Data Steward to the key business data elements. The assigned/owning Business Data Steward makes the decisions about the data elements and creates the metadata.

Choosing Key Business Data Elements

As mentioned in Chapter 2, bringing data elements under governance requires some effort. First, the Data Stewardship Council must decide on an owner for the elements. Next, the elements need to be defined, the creation and usage business rules ascertained, and the data quality rules documented. Often, the data has to be examined (“profiled”) to find out whether it meets the data quality rules. In addition to all this “setup” work, established procedures must then be followed for any changes to the key business data elements.

Since most companies have thousands of data elements, the very first thing you need to do is establish the most important (Key) Business Elements (KBEs) to focus on. If you think of the work done to bring data elements under governance as an investment, then it is reasonable to determine KBEs by the Return on Investment (ROI). That is, how important is it to the company that particular data elements be governed? Which data elements are worth spending the necessary time on? Or, to put it bluntly, what is the business case for spending time on these data elements when there is so much else to do?

Here are some types of data elements to consider in making this determination:

- Financial reporting data. Data that is reported to the financial community—and from which investment decisions may be made—must be governed. The good news is that the finance folks typically understand this requirement, and have usually long since defined their data elements, including the derivation rules. They are often frustrated by the fact that other parts of the company use the same terms to mean different things, and often welcome Data Governance, because it provides the opportunity for them to own their data and enforce their decisions, including having a common definition and derivation across the company. In fact, finance is often a great place to start working on Data Stewardship because of this.

- Compliance and regulatory data elements. Data that is required to be reported because of regulations must be governed. Regulations are notoriously bad about defining exactly what is needed, and often the company’s lawyers and regulatory experts must step in to clarify the options and provide additional details. Having a rigorous governance process and a clearly defined set of tools for recording decisions about regulatory data is key in answering questions from the regulators and documenting exactly how the reported results were calculated. Doing so can keep important people out of jail! At a large bank, fines were levied by regulators over several years due to violation of anti-money laundering rules. However, once these data elements were given a high priority, it was discovered that, in fact, the rules were not being violated—it just looked like they were because of poor-quality data. In this particular case, a direct monetary return could be attached—the value of the fines that no longer had to be paid—to bringing the data under governance (and thus tracing the information chain and locating where the poor quality was introduced).

- Data elements introduced by company executives. It should come as no surprise that terms (data elements) that figure prominently in presentations given by company executives need to have a high priority. You would think that when highly placed individuals in the company use terms regularly they would have a clear idea of what the terms mean and how they are measured. But that is rarely the case. In one example, the president of a large insurance company introduced a new metric that everyone in the company was going to have in their bonus program. The metric was calculated by dividing one number by another. However, when questioned, she was unable to fully define either of the two terms involved, despite having set a numerical goal to be reached! On another occasion, a senior executive created a presentation that explained how a “prospect” moved through the sales funnel to become a “lead,” then an “opportunity,” and finally a “customer.” However, except for “customer,” none of these terms were defined, nor did we have any way to determine when the change in state occurred. This situation needed to be addressed quickly as well.

- Data used by high-profile projects. As discussed earlier, large projects should have representation from Data Stewardship (Project Data Stewards), and the data used by high-profile projects should have a high priority for being brought under governance. Also, high-profile projects present the opportunity to bring data under governance in a managed way with the limited scope of the project. Ungoverned data raises the probability that the project will fail, or at least take longer and cost more than was originally predicted. High-profile projects catch the attention of important people when these failures occur. Examples of high-profile projects may include replacement of aging enterprise-critical systems, systems that provide distinct competitive advantage, and analytical systems such as data warehouses, especially when multiple failures have occurred in the past.

- The Business Data Stewards decide. One way to identify KBEs that is often overlooked is to let the Business Data Stewards decide what elements are important enough to be worthy of their attention. After all, they are the ones doing the work, so it only stands to reason that they would be willing to put work in on particularly troublesome data elements. And, as the data experts, Business Data Stewards are in a great position to know what data elements should be dealt with that would benefit their business function. And even if each steward only picks five data elements to work on at a time, the number of governed elements can build up quickly.

Subtle Definition Differences can be Important

We’ve all had business people tell us that writing down definitions for key business data elements is unnecessary because “everyone knows what it means.” At a macro level, this may occasionally be true, but detailed definitions and derivation rules can point out subtleties that are important. Robust definitions and derivations often explain differences in reported numbers and help resolve nagging inconsistencies. A good example is the definition of delinquency date that I encountered at a large bank. Two reports purported to show how many loans (and the total value of those loans) were delinquent—that is, payment on the loan was overdue. Yet the two reports—one from Loan Servicing and the other from Risk Management—showed two different sets of numbers. Each identified a different number of loans and the value of those loans differed as well. Both reports calculated the delinquent loans the same way—comparing the loan due date to the loan delinquency date. So how could they be different? The answer was in the definition of “delinquency date.” One report defined it as the date on which the loan became delinquent; the other report defined it as the next day. Once this difference was discovered, the Business Data Stewards agreed on a common definition and the reports reconciled. In fact, once the agreement was in place, the Risk Management group stopped running their report and began using the loan servicing report instead.

Another example involves the count and value of financial transactions on a travel agency website. Two different groups were reporting vastly different numbers for both, yet on the face of it, their definition for a “financial transaction” (to pay for reservations) was the same. It wasn’t until the Data Governance group delved into the discrepancy that things became clear. In one group, any attempted transaction was counted and the count was triggered any time an attempted payment occurred, whether the payment was successful or not. In the other group, only successful transactions were counted. Since credit card transactions are frequently rejected due to incorrect data being entered (e.g., the card number, expiration date, etc.), the counts were quite different. As it turned out, both numbers were important. The successful transactions represented actual financial commitments, while the total transactions represented costs to the travel agency as each transaction cost them money, regardless of whether it was successful or not. As is usual in such cases, the “financial transaction” was broken up into two separate terms—attempted financial transactions and completed financial transactions—with different business functions owning each term.

Assigning the Responsible Business Data Stewards

As KBEs are identified by the Business Data Stewards (with guidance from the Data Governance Program Office, DGPO), the very first thing that needs to be done is to assign a steward who will be responsible for that data element.

Note

The first law of Data Stewardship is that every governed data element must have at least one, and usually only one, Business Data Steward responsible for that element.

It is often clear (dare I say “obvious”) which business function should own the data element. Many data elements are collected by and for a single business function. For example, the policy information collected by an insurance company belongs to the underwriting business function. That isn’t to say that the data isn’t used by other business functions. That same policy information may be used by the accounting business function to bill customers and by the data management group to manage master customer data. When determining an owning business function, there are some key questions you need to ask:

- Whose business will fundamentally change if the definition or derivation of the data element were to change? There is a difference between using a data element and driving your business with it. As mentioned, accounting, finance, Master Data Management (MDM), risk management, and other groups may use the data. However, if the definition or derivation changes, these other groups can usually make a small change to the way they use the data and continue on as before. The owning business function, however, will be significantly impacted by any change. Put another way, which business function owns the core business processes that most depend on the data element?

- Where within a business process does the data element originate? Using the information chain concept, if the group that originates the element is responsible for it then the ownership is clear. With a well-documented information chain, the owner can see the implications of the various uses of the data element.

An example may help here. An insurance company identified their agents using a three-digit code. These representative IDs were used in all sorts of ways, including by finance to pay commissions on policies sold. Unfortunately, as the company grew, they found that they were running out of codes. The need, therefore, arose to expand the field, which was a major undertaking. It seemed reasonable to expect the owning business function to pay the costs, which led to the unusual circumstance that no one wanted to own the field! The argument was made that finance owned the field because they cut the commission checks, and without the code they couldn’t do that. But paying commissions is not a core finance process—that is, Finance could continue to operate just fine without cutting the checks. On the other hand, keeping track of the agents and what they sold was definitely a core underwriting process. Without an upgrade to the code, underwriting would not be able to identify agents, associate policies with the agents, and make sure that finance had the data needed to get the agents paid. The end result would be that the agents would leave the company and start selling someone else’s insurance, perhaps from a company that would pay them! In addition, all the existing policies would no longer have agents to manage them, leaving the company with the major headache of handling existing customers with a rapidly shrinking workforce! Given these facts, underwriting had to take ownership of the representative IDs and pay for the change.

This example also brings up another important role—that of a stakeholder. As stated earlier, decisions have impacts, and it is important for Business Data Stewards to understand the impacts. To do so they need a clear idea of who uses their data, and need to consult with those users to understand the impact that a decision would have on that usage (via a well-documented information chain). The users of the data—that is, those who are impacted by a decision—are the stakeholders. In the parlance of RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed), the stakeholders need to be consulted about a proposed decision. In the delinquency date example, Risk Management was a stakeholder, as they based many of their risk reports on the value of delinquent loans, and that would change with the new definition. In the representative ID example, Finance was a stakeholder, as they need to be able to accept the longer code, translate it into real people, and then cut the checks.

Creating Good Business Definitions

As stated earlier, one of the primary responsibilities for Business Data Stewards is to provide business definitions that clearly define what the element is and why it is important to the business. These definitions must meet the standards for a high-quality business definition.

A repeatable process must be established for identifying data elements and creating definitions for them, as discussed later in this chapter. The definition goes through various statuses, and different people contribute to the process as it moves to a finalized definition.

Characteristics of a Good Business Definition

So, what is a good business definition for a data element? We’ve all seen the bad ones—just the name of the element, or the name with the words switched around. But a good business definition should include the following to be complete and useful:

1. The definition of the term, using business language. The definition should be concise and describe the meaning of the data element. That is, we want to know (through the definition) how the business talks and thinks about the data element, nothow it is named and resides in a database.

2. What purpose the term serves to the business—how the business uses the information represented by the data element. The importance of the term to the business helps to clarify what the term means.

3. Must be specific enough to tell the term apart from similar data elements. This requirement often leads to qualifying or specializing a generically named term. This was what happened in the previous example with “financial transaction,” which became “attempted financial transaction” and “complete financial transaction.”

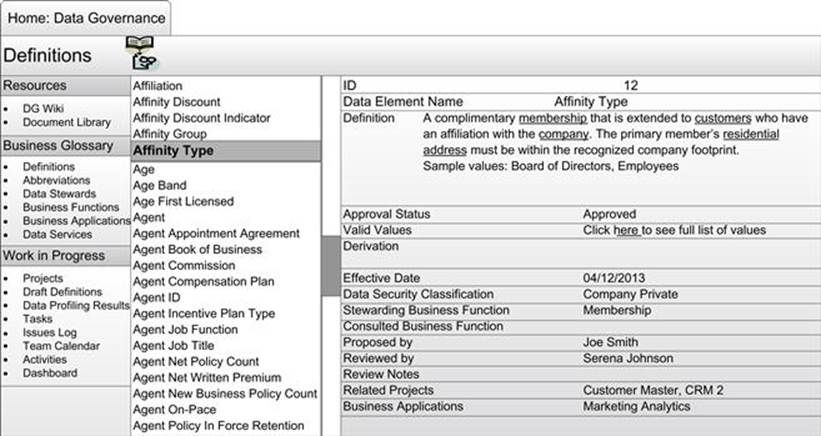

4. Should link to already-defined terms that are used in the definition (see Figure 6.8 later and notice the underlined terms in the definition). The key here is not to define (again) other terms that are already defined, but simply provide a link to those embedded definitions.

5. Should either state the creation business rules or link to them (See the section Defining the Creation and Usage Business Rules for a Data Element later in this chapter).

There are certain questions you can ask yourself to determine how complete and accurate the definition is. First, completeness—after reading the definition, does it leave you asking another question or wanting more detail? Next, can you provide a specific example that would not fit the definition as it stands? Finally, could someone new to the organization understand the definition? You have to be careful with this last question. It does not mean that someone who is completely unfamiliar with the industry should be able to understand the definition. Instead, all that should be necessary to understand the term is a general background and familiarity with other common terms. For example:

- Business term: Representative ID

- Poor definition: The identifier for a representative. (Generally, it is not acceptable to use the term in its own definition.)

- Good definition: Uniquely identifies the Agent or other representative who is directly responsible for a new or a renewed Insurance Policy. Data about a new account is filled in by the agent during the initial data entry process for the policy. Identifying the representative is crucial to measuring the productivity of the agent as well as for use when compensating the agent. This data is not captured when a customer logs in and fills out the insurance information directly using web-based access.

Note that ISO (International Standards Organization) has published a definition of a good definition (International Standards Organization, 2004-07-15, ISO/IEC 11179-4 Information Technology—Metadata Registries (MDR) Part 4, Formulation of Data Definitions, 2nd ed.). Section 4.1 provides requirements, such as the definition should be stated in the singular; it should state what the concept is, not only what it is not; it should be stated as a descriptive phrase or sentence(s); and it should be expressed without embedding the definitions of other data or underlying concepts. Section 4.2 additionally provides a set of recommendations, such as the definition should state the essential meaning of the concept; be precise and unambiguous; it should be able to stand alone; and it should be expressed without embedding rationale, functional usage, or procedural information.

Defining the Creation and Usage Business Rules for a Data Element

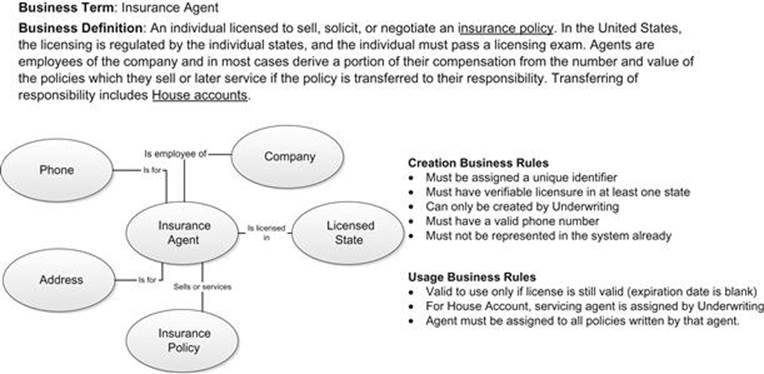

Defining the creation and usage business rules is key to ensuring that (not surprisingly) the data is created only when it is appropriate to do so, and used only for the purposes for which it was designed. Figure 6.1 shows an example of a defined element with its listed business rules. Since the quality of the data (and the perceived quality) are often negatively impacted by improperly creating data or using it for purposes for which it was not designed, having and following the creation and usage business rules can go a long way toward protecting the data quality.

FIGURE 6.1 Business rules for a term and the associated definition. The conceptual model shows how the insurance agent is related to other important terms, such as the licensing state.

The creation rules for a data element state the specific conditions under which an instance of the data can be created. They may include:

- At what point in the business process the data must be created or captured, and any circumstances under which it may not be created.

- What other data must be present and available prior to creating the data.

- Which business function is allowed to create the data.

- What approval process (if any) is needed before the data can be used in production.

The usage rules state how (and for what purpose) the data is allowed to be used. These rules may include:

- Validity tests that must be applied and passed before the data can be used.

- Relationships to other data that must exist.

- What business processes must use the data and in the way in which each process uses the data.

Tip

It can be very helpful to show the conceptual model of the relationships between major pieces of data when defining and stating the business rules for the term. See Figure 6.1 for an example.

Defining the Derivation Rules

The values of many data elements are derived. Some of these derivations are direct numerical calculations, such as “loan to value” in banking. For each derived data element, it is critical that a single, well-documented equation be used to calculate the quantity consistently across the enterprise. Otherwise, different reports purporting to display the same calculated quantity will not agree. It is also crucial that the component parts of the calculated quantity be themselves consistently defined (and if derived, derived in a consistent way). For example, what is the value of “loan” in the equation? Is it the original mortgage value with closing costs and points? Without closing costs and points? Our earlier example of the loan delinquency date is another calculated quantity—the due date of the payment plus a contractually agreed-on grace period. But the due date itself is a derived quantity based on the origination date of the loan and the period between payments.

Some terms (especially those with a specified set of valid values) may also be derived based on a triggering event. Some are relatively simple—an insurance policy status is considered “active” if the current date is less than the expiration date of the policy. Other data elements are more complex to derive. At the same insurance company, a person was considered a “customer” if he or she was actively doing business with the company, had ever done business with the company, or showed a willingness to do business with the company. The tricky part of the definition was that last bit—the willingness to do business. Sales (who owned “customer”) defined willingness to do business as someone who had received a quote on a policy. That is, when looking at the sales funnel, a person moved from “prospect” to “customer” when they received a quote. This definition made it not only important to know when a particular person received a quote, but also to be able to identify a person uniquely before they were a customer.

Setting Up Repeatable Processes

Having a set of repeatable Data Stewardship processes is one key to a successful Data Stewardship implementation, and ultimately leads to better management of data (which is, after all, the goal of Data Stewardship). One of the biggest issues with current data management is that people all tend to manage data differently. Having a set of repeatable Data Stewardship processes helps bring consistency to overall data management. With documented processes, everyone is aware of how to proceed to get a specific job done, what the steps in the workflow are, and who is responsible for each step in the process.

Note

In Chapter 5 (Figures 5.2 and 5.3) we saw some sample repeatable Data Stewardship processes.

As the Data Stewardship effort matures, you will find that you are adding processes as needed. The essential processes are listed here, though your organization may require others as well:

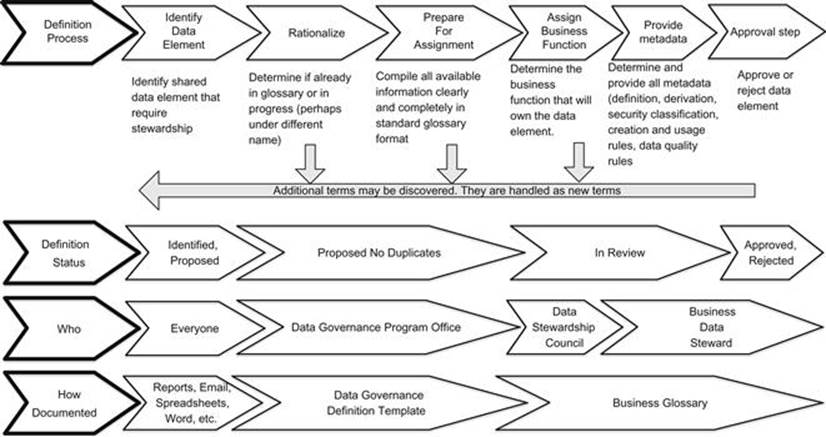

- Bringing new data elements under governance (Figure 6.2)

FIGURE 6.2 The flow (across the top) of the process to identify, assign business function owner, define, and approve a new data element.

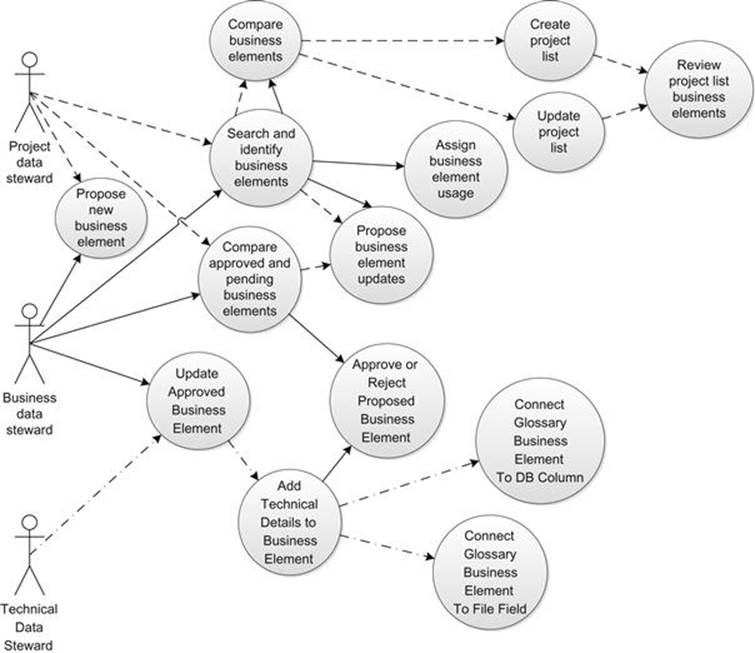

- Managing the business glossary (Figure 6.3)

FIGURE 6.3 The use cases (with actors) for adding, modifying, and removing business data elements in the business glossary, as well as mapping the business data elements to the physical data elements.

- Evaluating and finding resolutions for data quality issues

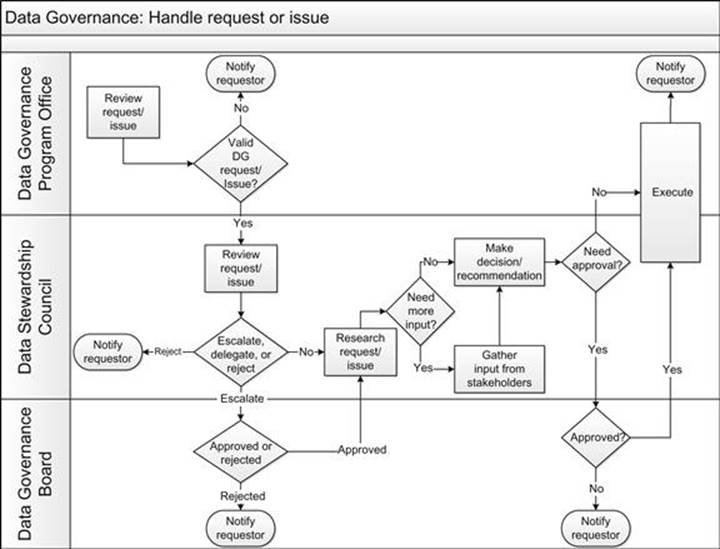

- Resolving a Data Governance request or issue (Figure 6.4)

FIGURE 6.4 A “swim lane” diagram that shows the steps and decision points for managing a Data Governance issue or request. The horizontal swim lanes indicate which role(s) are responsible for each step in the process.

- Managing policies, procedures, and metrics

- Coordinating the work of multiple Project Data Stewards

- Managing the issue log

Note

There are a variety of ways to document processes. While Figure 6.4 uses swim lanes, Figure 6.2 uses a straightforward flow, and Figure 6.3 uses a set of use cases. You should pick the format that works best for your audience and for the nature of the process that you need to document.

Workflow

To track the progress of repeatable processes efficiently, Data Stewardship is going to eventually need a tool with configurable workflow capabilities. Manually tracking statuses and attempting to shepherd processes through the required steps is both tedious and error-prone. In addition, a tool with workflow can automatically perform certain tasks, such as moving a process to a secondary approver if it has sat too long in the primary approver’s queue (e.g., if the primary approver is on vacation). Further, reports generated from the tool can show how many processes are at what stage, and if there is a bottleneck (e.g., one particular approver who takes a long time to do their work).

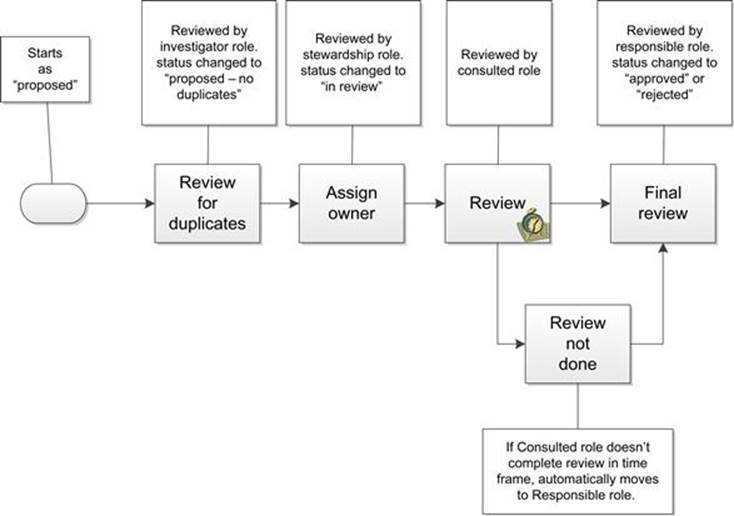

The workflow tool must be configurable because the workflows change over time and different kinds of tasks require different levels of workflow rigor. For example, a two-step approval process may prove to be too cumbersome, and the Data Stewardship Council could decide to dispense with one of the steps. Figure 6.5 shows an example of a new data element moving through the approval process.

FIGURE 6.5 Workflow for approval of a business data element in the business glossary.

Understanding How the Business Data Stewards Interact With the Data Governance Program Office

The DGPO staff needs to work closely with the Business Data Stewards on an ongoing basis. One key to a successful collaboration is to respect the Data Steward’s time. Frequent or purposeless meetings can quickly sour the steward’s willingness to participate in the Data Governance program. And while high-level support from the executives can mandate this participation, it is much better to have the stewards participate willingly. This is far more likely to happen if the demands on their time are limited to a reasonable amount, and each meeting that is held is purposeful and clearly results in value added for the Data Stewardship effort.

Tip

You should never have a meeting without an agenda, nor an agenda without goals. With goals (and an agenda that drives toward those goals), you can state what should be achieved in the meeting and whether those goals were actually achieved. Data Stewards are far more likely to attend a meeting that has goals they are interested in!

Regular Meetings with the Data Stewards

The key guidance for meetings is that you don’t schedule a meeting every time an issue comes up. Instead, regular general meetings should be scheduled for items like:

- Developments and issues related to the overall Data Stewardship effort. These can include organizational changes, new lines of business, new demands being placed on Data Stewardship by the Executive Steering Committee, and major data-related issues that require a concerted and coordinated effort by the Data Stewards.

- Training and updates on Data Stewardship tools. New tools or major updates to existing tools may require that the stewards be brought up to date on tool usage, including moving existing manual processes to an automated tool. Training is critically important, and should be done as close to the time of the tool change as possible.

- New and improved processes and procedures. As new processes and procedures are worked out, or existing ones are revised to make them more robust or efficient, the Data Stewards need to be made familiar with these changes. It is best to review such changes as a group if possible, because the group dynamics can lead to valuable feedback on the efficacy of the changes.

- Planning for major enterprise efforts that require Data Stewardship participation. Major data quality improvement efforts, MDM projects, and data warehousing initiatives all require significant input from the Data Stewards. Without careful planning and analysis of the level of effort and timing, Data Stewards can be overwhelmed. Meeting as a group—and including the project managers where possible—can help alleviate this risk and set realistic expectations. In addition, such meetings can make the overall stewardship effort more efficient since they provide an opportunity for stewards to apply their past experience to these new situations.

![]() In the Real World

In the Real World

Periodic assignment meetings are needed to assign ownership of new key business data elements. As discussed previously, new elements can pop up from many sources, and it is important to get ownership assigned early in the process. How frequently the assignment meetings are needed depends on the rate at which new data elements need to be brought under governance, but it is not unusual to have meetings weekly or every two weeks. The frequency of the assignment meetings will also depend on where you are in your governance process. As the Business Data Stewards get more experienced in determining ownership, the process will go faster, and meetings will not need to be held as often.

A good set of steps to follow for assignment meetings starts with gathering up potential names and as good a definition as possible for the data elements. These should then be forwarded to the members of the Data Stewardship Council, along with an invite to the assignment meeting. The Data Stewards who have an interest in the data elements would then show up to the meeting; those who don’t have any interest would not have to attend. For example, if there is a set of insurance data elements, the human resources steward would not need to attend. This approach keeps the audience to a small number of interested parties, rather than forcing everyone to attend. The stewards who do attend can then agree on ownership.

Note that if the attending stewards realize that someone is missing who might well need to be an owner, the Enterprise Data Steward (who runs these meetings) can circle back with the missing party to see if they agree on the ownership assignment.

Using Interactive Forums

A great deal of the rest of the work and coordination between the DGPO and Data Stewards can be done through an interactive forum. That is, instead of holding meetings that many cannot attend, items can be posted on an interactive, web-based “bulletin board” such as a SharePoint website, and responded to at the convenience of the stewards. Examples of items that lend themselves to this sort of management are:

- Input on metadata definitions and derivations

- Creation and usage rules review

- Data quality rules review

- Evaluation of data profiling results

- General requests for feedback on issues

Using the interactive forum might work something like this:

1. A Data Steward or member of the DGPO would open an issue or discussion point on the forum and request feedback. Depending on how Data Governance was set up, a stakeholder, designated subject-matter expert, or impacted data analyst might also be able to open an item.

2. Members of the Data Stewardship Council would be notified about the open issue or item. This would most probably work by subscribing the members of the council to the list so they would get automatic notifications.

3. The members of the council would provide their feedback at their convenience, and the Enterprise Data Steward would monitor the discussion and provide periodic summaries or propose remedies.

4. If the issue had to be escalated, the Enterprise Data Steward would escalate it to the Data Governance Board members. This might work as a separate issue list for the Data Governors, or it might require an email and/or meeting to be held, managed by the Data Governance Manager.

5. Once a reasonable solution was found, the solution could be posted to the list for feedback or voting.

The main advantages to managing the appropriate items this way are three-fold. First, the stewards are notified automatically of all issues that may require their attention. Second, they are able to do their research and respond at their own convenience, which means that meetings with the entire group don’t need to be scheduled. Last, there is a clearly documented trail of discussions that were held and solutions proposed. No one has to keep track of multiple email threads to document what was discussed.

TIP

Success with online collaboration also depends on the company culture. In some organizations, people interact effectively online. In other organizations, if there has not been a meeting on a topic, then the topic remains open. It takes some prework within an organization to get people adjusted to the approach of online collaboration.

Using Working Groups

Between full Data Stewardship Council meetings and using the interactive forum(s) is the possibility of forming working groups. These are committees formed by Business Data Stewards who are responsible for gathering feedback from interested parties to resolve an issue or settle a disagreement. The working groups are needed when a question requires widespread input from the business community. The steward schedules and runs the meetings; the participants are business users who are impacted by items, such as:

- A proposed change to a data element definition or derivation

- Detection and correction of a perceived data quality problem, including revising data quality rules

- Changes to usage and creation business rules

The organizing steward is accountable for getting the issue resolved and bringing back a consensus to the Data Stewardship Council to propose adoption and sign-off where appropriate.

In the Real Life

An example from the insurance world should help to illustrate how an interactive forum (called a discussion board at this company) and a set of working group meetings helped to resolve an issue around a key term: “close ratio.” The process for resolving this issue also closely followed the process flow illustrated in Figure 6.2.

The term “close ratio” had been defined, approved, and entered in the business glossary by the owning business function (Sales). However, during a project, the term came up in internal discussions, and business people were confused by the usage and name. They therefore decided to change the definition. Fortunately, one of the team was aware of the DGPO, and advised the project team that they did not have the authority to make the change. Data Governance was then engaged in the process (Identify in Figure 6.2).

The sales Business Data Steward got a working group of the concerned participants together, who voiced their concerns and the confusion around what the term meant. The steward then created an issue on the discussion board, listing those concerns, and subscribed everyone in the working group to the issue. People individually stated what they thought the definition should be, as well as identifying variations on the term that could be considered as additional data terms. The steward then proposed the names and definitions on the discussion board (Rationalize). The assignment (to Sales) did not change. The discussion board entries fleshed out the full definition of the renamed term (“unique quote to close ratio”), the additional identified terms, and how the term was derived (Define/Derive). In the end, the revised definition was entered in the business glossary (Finalize and Document) and the Sales Business Data Steward approved it.

If you are interested in seeing the very complete definition and derivation associated with this business term, please see Appendix A.

How Project Data Stewards Work with Business Data Stewards

Project Data Stewards represent Data Stewardship on projects. The challenge of being a Project Data Steward is that you need to balance the needs of the project (which are likely to be immediate and time-constrained) with the needs of the Data Stewardship program (which necessarily has to have the bigger picture in mind). This is made more difficult because the Project Data Steward does not have the authority to make decisions, and must consult with the Business Data Steward. Use the following guidelines for Project Data Stewards to work with the Business Data Stewards:

- First and foremost, it is important not to overwhelm the Business Data Stewards. Make sure that the Business Data Stewards are aware that the Project Data Stewards will be working with them. In addition, Business Data Stewards need to include the interaction with Project Data Stewards in their time estimates (and time limits).

- The Project Data Steward should attempt to collect as much of a definition, derivation, and data quality rule(s) from the project business analysts and subject-matter experts. This information is then brought to the Business Data Steward. If (as often happens) the data element is the subject of a debate within the project team, the Project Data Steward should collect all the opinions presented so the Business Data Steward has as much information as possible. In other words, the Project Data Stewards should do their homework on any questions or concerns that they may need to bring to the Business Data Stewards.

- For data quality questions, data profiling should be performed and the results reviewed with the project team before bringing the information to the Business Data Steward. The data profiling shows what is actually in the database (rather than guessing at that information) and the project participants may decide that the condition of the data does not represent an issue for the project after viewing those results. In that circumstance, the Business Data Steward may not need to provide input. Nonetheless, it is still usually a good idea to share the results with the Business Data Steward, who may see something that the project members do not.

- Project Data Stewards should compare their project data element lists to cull duplicates so that different Project Data Stewards don’t end up asking the Business Data Steward about the same data element.

- If a Business Data Steward has not yet been identified for the project data elements, the question should come to the Enterprise Data Steward to identify a potential steward using the assignment process.

Using an Issue Log to Get the Day-To-Day Work Done

Data that is considered to be under governance has issues worked through an issue log. By using a centralized issue log and working on the issues using a set of well-defined processes, a clear picture of the status of issues can be provided to stakeholders. In addition, priorities can be established and resources allocated to getting the work done.

What is the Issue Log?

No too surprisingly, the issue log is where issues and questions about governed data are documented, worked on, and resolved. That is, the issue log is about tracking and knowing what the issues are, what their status is, and what impact they have. Resolving an issue may take the form of reaching a simple agreement or agreeing to a proposal to remediate the issue. Agreeing to a proposal is necessary when technical changes (which may require a project) are needed to remediate the issue. Understand also that remediating an issue may require that additional data be governed, perhaps because the data has become important (as described earlier in this chapter).

Managing the Issue Log

The issue log is usually managed by someone from the DGPO, often the Enterprise Data Steward. That doesn’t mean, however, that the DGPO staff is responsible for doing all the input. Depending on how permissions are set up, issues and questions can be entered by Business Data Stewards, Data Governors, stakeholders, and others. However, the DGPO staff is responsible for ensuring that all the pertinent information is entered for each issue or question. This is an important responsibility: if issues are poorly defined, it is really hard to resolve them. In addition, if someone is not actively managing the issue log, then there is a risk of duplicate entries, erroneous entries, or issues that are never addressed.

Issue Log Fields

To properly record issues and questions in the issue log, you need the right set of fields. Although you will need to tune this list for your own requirements, here is a starting list of fields that should help get you going. These fields are adopted from Collibra’s Data Governance Center tool, and are used by permission:

Issue description: A description of the issue and why it is important that it be dealt with. For example, it is not good enough to simply state that the meaning of a location code changed; the description must also state that the change could lead to staffing errors and how that might happen.

Analysis: Records the results of analyzing the issue, ideas on root causes, potential solutions, and impacts to the information chain and processes. Analysis should include as much as possible quantification of the issue (number of records impacted, timeframes impacted, number of customers or business areas impacted).

Resolution: The chosen solution and reasons for that choice. Note that the solution may be to do nothing and accept the risks associated with that choice. Those risks should be listed in this field as well.

Priority: The importance of the issue, chosen from an agreed-on set of priorities (properly documented, of course!).

Related to: This documents any connection from the issue to any other type of enterprise asset. For example, if the issue is poor data quality, the “related to” could be the business data element and the physical data element (and the system it is in). The data quality rule that is being violated is documented in the “violates” field (see below).

Impacted by: This documents any connection from the issue to any other type of enterprise asset that impacts the issue. For example, another issue could impact this issue.

Requestor: The person who submitted the issue.

Reviewer: The person who reviews the issue, reviews the resolution, assigns priority, or in some way needs to provide input. Multiple persons can be listed.

Assignee: The person responsible for handling and resolving the issue.

Violates: Governance assets (e.g., a data quality rule) that the issue is violating.

Resolved by: Governance assets (e.g., a new procedure, policy, or rule) that are put in place to prevent the issue from reoccurring.

Business function domain: The business function and/or data domain that owns the issue.

Date the issue was identified.

Understanding the Issue Log Processes

Working on the issues and questions in the issue log requires executing on a well-defined set of processes to drive to a solution or remediation. The tasks involved are listed and defined in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1

Issue Log Processes, Descriptions, and Who is Responsible

|

Task |

Description |

Responsible |

|

Log |

This task involves logging a description of the issue, including what the issue is, who noticed it, the extent of the issue (how many records, over what time period, etc.), and a statement as to the possible negative impacts to the company. It is important to fill in as many of the fields noted in the last section as possible—the better the information logged, the easier it will be to find a solution. |

The issue should be logged by a member of the DGPO staff and possibly Business Data Stewards. However, anyone can report an issue to have it logged. |

|

Research |

This task largely consists of validating that the reported issue actually is an issue, and if it is, locating the root cause of the issue. The research should be carried out by either the Business Data Steward responsible for the data, or by a team led by that individual. |

Business Data Steward(s) |

|

Propose solution |

Once the root cause is identified, the people most knowledgeable about the affected data can propose a solution to alleviate the issue. Potential solutions could be making a simple workaround, making system changes, or even instituting a major project. The proposed solution should also include the impacts to the information chain, including systems, reports, data stores, ETL, and Data Governance tools such as the metadata repository. It is likely that IT support will be needed to identify the impacts. |

Business Data Stewards Technical Data Stewards |

|

Escalate |

Since many issues cannot be solved at the Data Stewardship Council level, the next step is to escalate to the Data Governance Board for prioritization and approval. For large issues, or where board members cannot agree on proposed solutions, it may be necessary to escalate to the Executive Steering Committee. |

Business Data Stewards Data Governors Executive Steering Committee member(s) |

|

Prioritize |

When multiple issues must be dealt with (the normal case), prioritization is necessary. This consists of establishing the order in which issues will be worked, as well as the resources (both people and funding) that will work the issue. At this stage it will be necessary to get cost estimates from IT as part of the input to the decision. In addition, other efforts (e.g., major implementations) can have significant effect on the priority of an issue. |

Data Governor(s)Executive Steering Committee member(s)Technical Data Steward(s) |

|

Approve |

This step is where people with sufficient authority approve the plan and resource allocation, or, alternatively, choose to reject remediation of the issue and accept the impacts and risks associated with doing so. |

Data Governor(s)Executive Steering Committee members(s) |

|

Communicate |

This task involves making all impacted parties aware of how the issue is going to be resolved (or not resolved). It is a parallel task to all the others. That is, interested parties should be able to track the issue through the process and provide input as necessary. |

DGPO |

Documenting and Communicating the Decisions

Once decisions have been made, it is extremely important to document those decisions so that they are easily available to all interested parties. For example, anyone who wonders how a particular data element is defined or derived should be able to easily find that term in the business glossary. Successful information sharing obviously requires that the interested parties are aware that definitions are being created, and that they are being stored in something called the business glossary! To put it more generally, people need to know that information exists, and how to get it (or ask for it).

Major decisions made by stewards must be documented for the business community, and notification about those decisions made as well. A solid communication plan is an absolute imperative to communicate decisions and developments to the business and IT.

Note

Various tools may include publish and subscribe mechanisms so people can get periodic notifications about issues and decisions. Summary reports are also useful, especially for executives and Data Governors.

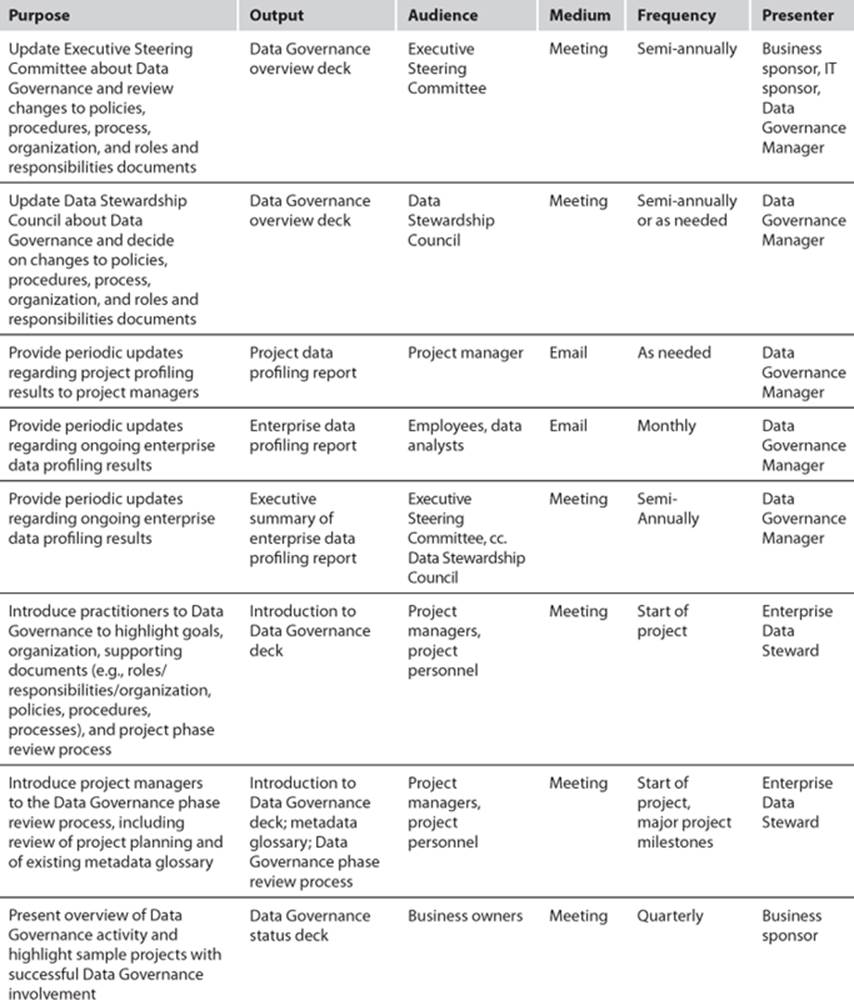

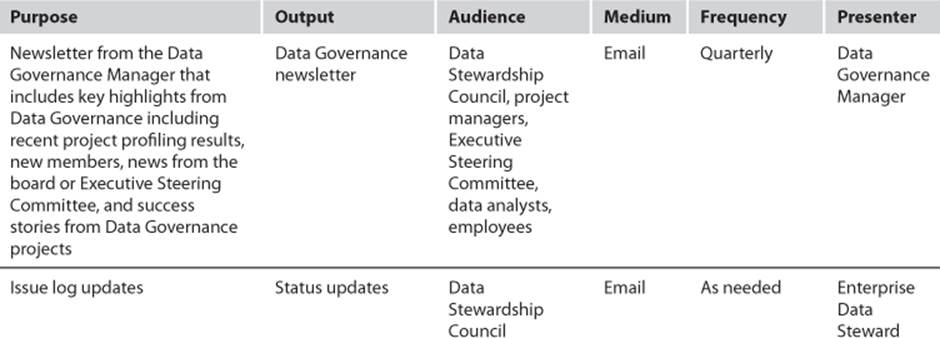

The good news is that since Data Stewardship is part of Data Governance, a communications plan should have been built early in the implementation of Data Governance. This plan (see Table 6.2 for an example) should, at a minimum, include:

- The purpose that the communication serves.

- The title of the communication output.

- The audience for the communication. This normally consists of various groups within the enterprise who will benefit from this information, including project managers, developers, Data Governors, and Data Stewards.

- The communication medium. Information can be communicated in various ways, such as meetings, emails, pushed via subscriptions, and so on.

- The frequency in which the communication is issued.

- What role is responsible for presenting the communication to the audience.

Table 6.2

Data Stewardship Communications Plan Sample

Data Stewardship progress should also be included in normal company publications, so that the “general public” is made aware (and kept aware) of the efforts going on in Data Stewardship. Table 6.3 shows how a schedule of company publications might look. The Content column is a general classification of the type of content included in the article. The Article Title/Heading column is the name of the column or article in the publication. For example, each company newsletter has a column called “Passport,” and the “What’s going on?” information is included in the column.

Table 6.3

Company Publication Schedule for Data Stewardship

|

Content |

Article Title/Heading |

Frequency |

|

What’s going on? |

Newsletter column: Passport |

Every other month |

|

Information just in time |

Newsletter column: What You Need to Know |

Every other month |

|

Data Stewardship milestones |

Web column: Company Achievements |

Quarterly |

Specifying the Data Stewardship Tools

There are four important tools that can help document the Data Stewardship effort and communicate the results of these efforts. The four tools are the Data Stewardship portal, the Data Stewardship Wiki, the business glossary, and a metadata repository. Note that the Data Stewardship portal should include links to the other tools, and usually displays the contents of the Wiki and possibly the business glossary and issue log as well.

Note

These tools are in addition to the issue log, discussed previously.

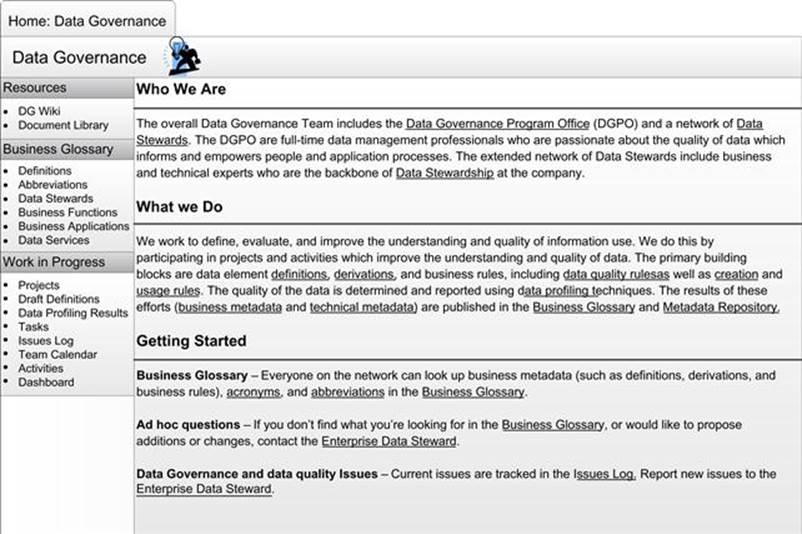

Data Stewardship Portal

It is imperative that Data Stewardship efforts be transparent. People directly involved with Data Governance and Data Stewardship (e.g., members of the DGPO, Business Data Stewards, Data Governance board members, etc.) and people who need and use the information provided by the Data Stewardship effort (which should be pretty much everyone else) should have a web portal where they can find what they need. The web portal should provide staffing information, links to other tools (e.g., the business glossary), and links to status reports, policies, procedures, issues, and contact information.

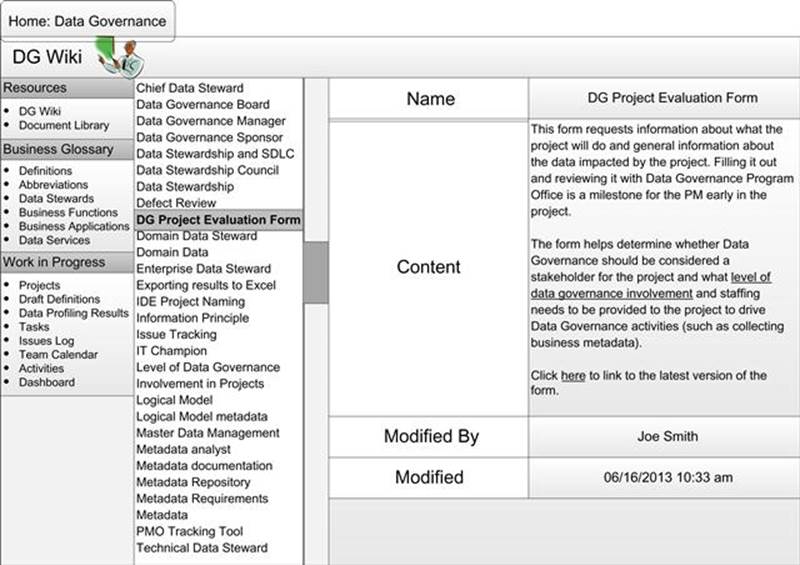

In addition, the web portal homepage should provide a brief description of “who we are” and “what we do.” Think of these sections as the “one-minute elevator speech” version of Data Stewardship. Figure 6.6 shows a sample of what a web portal homepage might look like.

FIGURE 6.6 A sample Data Stewardship web portal homepage.

Data Stewardship Wiki

Data Stewardship and Data Governance use many specialized terms, forms, and processes. As these are defined, they need to be documented and easily available to the target audience. Documenting everything also improves the standardizing of these terms, forms, and processes. Figure 6.7 shows a sample of what a Data Stewardship Wiki might look like, and a sample of the terms that could be present and available.

FIGURE 6.7 A sample Data Stewardship Wiki page.

A Critical Artifact: The Business Glossary

To manage data as an asset, the data must be inventoried. That is, you must document the answer to the question “What data elements do we have (and which ones are we tracking)?” The place to do that is the business glossary, which is a tool that records and helps to manage business data and metadata. Much of the process of bringing data under governance involves business-focused metadata, such as business terms, data definitions, derivations, data quality requirements, business rules, and stewardship. This information should all be found in the business glossary, and be accessible to everyone in the enterprise. It is also helpful to be able to classify the terms in a taxonomy. In addition, a good business glossary should manage the routing and workflow related to the business metadata, such as drafting and approving definitions.

The business glossary (along with a robust search function and warning for potential duplicates) enables Business Data Stewards to rationalize the data, picking out the unique elements from those that are actually the same data but with variations in business names (or the same names but different data). Most data analysts want to name data elements however they feel like it, and don’t recognize that the naming that works for them may not work for everyone else. As a result, data analysts often don’t provide data element names that are specific enough. Data Stewards have to deal with these naming inconsistencies and must ensure that an agreed-on and rigorous naming standard is followed when creating data element names. For example, Table 6.4 shows how much of a difference proper naming can make in inventorying the data.

Table 6.4

Rationalizing the Data Elements

|

Data Element |

Different Names or Different Data? |

Total Data Points |

|

Entry time |

Ticket issue ime, time of entry, transaction start time |

1 or 4? |

|

Prepayment time |

Ticket paid time, payment time |

1 or 3? |

|

Amount due |

Transaction total, transaction amount |

1 or 3? |

|

Payment method |

Payment type |

1 or 2? |

|

Amount tendered |

Amount paid, collected amount |

1 or 3? |

|

Change issued |

Overpayment amount, refund amount, amount due to client |

1 or 4? |

|

Receipt issued |

Receipt requested, receipt printed |

1 or 3? |

|

Actual exit time |

Exit time, departure ime |

1 or 3? |

|

Total |

8 or 25? |

The business glossary is where the business metadata is published. This metadata should include the business name, definition, derivation, valid values (where appropriate), any usage notes, data security classification, the stewarding business function, approval status, any related projects, related definitions, consulted business function (for domain data), effective date, proposed by, reviewed by, review notes, applications known to use this data, and reference documents. The key deliverable is a set of business names with stewards/owners (as shown in Table 6.5). Figure 6.8 shows a sample of how an element in the business glossary might look.

Building a Hierarchy of Terms

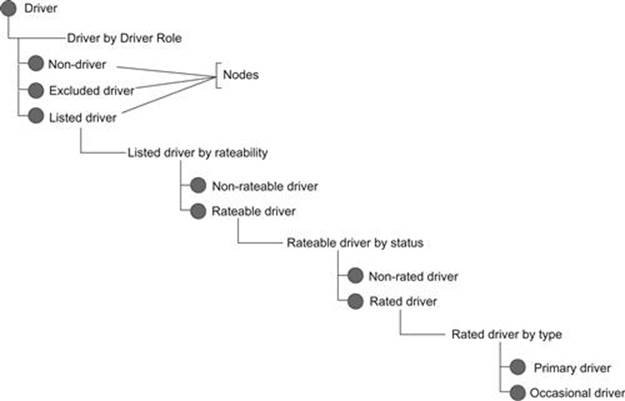

One capability of a robust business glossary is the ability to define a semantic hierarchy of terms. A hierarchy enables the Data Stewards to classify their terms and show the relationships between them. It also helps to sort out a multitude of terms that seem to overlap or conflict in meaning. By building a hierarchy and defining each node, a clear picture of the meaning and relationships between terms can be derived.

A good example was the large number of terms used in referring to a “driver” in an automobile insurance policy. These terms included “excluded driver,” “nonratable driver,” “nonrated driver,” and “primary driver.” By building the hierarchy shown in Figure 6.9 and defining each node, it was possible to create a coherent picture of these related terms.

Table 6.5

Business Names, Definitions, and Owner/Stewards

|

Data Element Name |

Definition |

Steward/Owner |

|

Location |

Any place where customers do business with the company. Includes all types of locations, such as a branch, express outlet, contact center, main office, and Internet. |

Sales |

|

Location ID |

A unique identifier for a location, such as company location ID, office number, branch ID. |

Sales |

|

Policyholder tenure |

The number of years a member has owned a policy with the company, including affiliated companies in other states. |

Sales |

|

Collection posting date |

The date on which the collection amount was recovered by the company. |

Financial operations |

|

Retired employee indicator |

Identifies whether or not a person is a retired employee of the company. |

HR |

|

Accident surcharge waiver indicator |

Identifies whether the surcharge for an accident was waived during the rating process based on certain business rules—that is, accident forgiveness indicator. |

Underwriting |

|

Accounting state |

Residential address state where the policyholder resided at the time a new business transaction took place. |

Financial reporting |

|

Assumed earned premium |

Earned premium assumed from another insurer, when the company is the reinsurer. As a reinsurer assuming risk from another insurer, we effectively assume part of the risk and part of the premium originally taken by the primary insurer. |

Financial reporting |

FIGURE 6.8 A sample screen from a Data Stewardship business glossary.

FIGURE 6.9 A hierarchical description of the terms related to “driver.”

A Metadata Repository

At its most basic level, a Metadata Repository (MDR) is a tool for storing metadata. In some cases, the MDR is largely focused on recording physical and technical metadata, such as data models, database structures, metadata associated with business intelligence tools (e.g., Business Objects universes), ETL, copylibs, file structures, and so on. Business metadata (e.g., business data elements, definitions, business rules, etc.) is often thought of as being stored in a business glossary, but many commercial MDR products include the business glossary component. The MDR can provide impact analysis for proposed changes, and lineage (where data came from and how it was manipulated). The MDR should also provide the link between the business term (in the business glossary) and the physical implementation of that term. Finally, rules (e.g., the list of valid values for a data element) should be documented, and in sophisticated MDRs, even managed from the repository.

A MDR is crucial to Data Stewardship because of the ability to link the business data element to its (potentially) many physical implementations. This is crucial for:

- Impact analysis. When changes are proposed, it is very important to know everywhere the data exists so that the impact (a key deliverable from the Data Stewards) can be assessed and the proposed change can be propagated everywhere the data element exists.

- Data quality improvement. To assess the quality of data (and potentially improve it), the data must profiled so that the actual quality can be compared against the stated quality needed for business purposes. This process usually starts by identifying a business data element; however, the profiling assesses the physical data in the database. Thus, it is necessary to establish a link from the business data element to the database element. This is accomplished using the tools in a metadata repository.

Summary

Practical Data Stewardship includes choosing key business data elements based on their value, and then assigning responsibility and determining and documenting the business metadata (definition, derivation, and creation and usage business rules) for those data elements.

To execute on Data Stewardship, issues must be recorded and worked on in an issue log using repeatable processes driven by workflow. These processes include rules for the interactions between the Data Stewards and between the stewards and the DGPO.

A robust set of tools—including a portal, Wiki, business glossary, and metadata repository—are also instrumental in documenting and publishing the progress of the stewardship effort as well. More importantly, these tools enable the effort to have the desired impact and be easily accessible to those who need the output from the Data Stewardship program. On top of the tools, a communications plan must be designed and used to let everyone know what Data Stewardship is, and what it is accomplishing.