Intertwingled: Information Changes Everything (2014)

Chapter 4, Culture

“The power of authoritative knowledge is not that it is correct but that it counts.”

– Brigitte Jordan

They stride into the arena wearing the maize and blue. They are tall, strong, fast, and confident they will conquer the world. It wasn’t easy getting here, but after countless hours of practice, weight training, and gut-busting cardio workouts, they have arrived. The price is high. It costs thousands of dollars a year to play at this level, but without access to the best coaches, facilities, and technologies, you might as well just go home.

It’s six-thirty in the morning in January, and as I watch our fourteen year old daughter’s volleyball team make their way to the court, my feelings are mixed. I’m not happy about waking up at five o’clock on a Saturday to drive for an hour through the snow. A few years ago, I’d have laughed at this elite sports scene. Now I’m a part of it. Claire is staying fit, making friends, building self-confidence, learning teamwork.

Still, it’s over the top. Our club makes me uneasy. What bothers me most is the uniforms. They are beautiful. Since our club is run by the University of Michigan, our girls are decked out in blue and gold. While a lot of teams satisfice with cotton t-shirts, we have personalized, lightweight, wicking Nike jerseys with matching shorts, warm ups, and backpacks. As our girls prepare to play, I can’t help feeling we’re on the wrong side of the tracks. And sure enough, we are crushed by the t-shirt team, just like in the movies. Later, after a day of losses, I tell Claire not to worry, it’s the first tournament of a six-month season, the team will get better.

Of course, it was all downhill from there. Our coach was a hard-ass all season. One girl was berated for not hitting hard enough. Later it turned out her finger was broken. Claire was told she couldn’t take a break even though she felt sick. Soon after she was vomiting into a bucket. The girls were taught how to trick the referee. They were instructed to lie. The coach invited them to voice complaints. Claire did so and found herself benched. The parents weren’t any better. Our alpha mom reduced other moms to tears, taunted the opposing teams, and paid for weekly private lessons with the coach. This looked like pay-to-play corruption to us, but several of the parents said that’s simply how you play the game.

The next year we switched clubs. The new one was a little less expensive and a whole lot better. When the coach told the girls it was okay to miss practice for homework, since education is more important than volleyball, he actually meant it. When we lose a game, you won’t hear a word from our alpha mom. We don’t have one. The girls practice in an old warehouse, no windows, flickering lights. It’s nothing fancy. Neither are the uniforms. And that’s the way we like it. We found our fit.

Cultural Fit

In the 1990s, as co-owner and CEO of a consulting practice, I hired and managed several dozen employees. Mostly we got it right, but once in a while we hired someone who didn’t fit. The consequence of a cultural mismatch is often compared to an immune system response. It’s not a bad analogy. The first symptom is inflammation. This pain is followed by isolation of the foreign body. But in organizations, there’s no need to destroy the antigen. Few people endure outsider status for long. They quit. At the time I thought there was something wrong with those people. My enculturation was complete. Now I know it simply wasn’t a good fit.

As a consultant for two decades, I’ve been a tourist in all sorts of cultures. I’ve worked with startups, Fortune 500 companies, nonprofits, Ivy League colleges, and Federal Government agencies in multiple countries. My clients have included folks from marketing, support, human resources, engineering, and design. Being exposed to diverse ways of knowing and doing is one of the best parts of my work. But my interest runs deeper than cultural tourism. Over the years, I’ve realized that understanding culture is central to what I do.

First, as an information architect, I must understand the culture of users. When I run a “usability test,” evaluating the system is only half my aim. I also hope to uncover the beliefs, values, and behaviors of the people who use the system. Before imposing my own theories, I want to see how they define their world. What can we learn from their use of language and the way they sort concepts into categories? Which sources of information and authority do they trust? What is the meaning behind their behavior? For years, I’ve used lightweight forms of design ethnography as part of my user research practice. It’s helped me to better understand and design for oncologists, middle school children, university faculty, bargain hunters, and network engineers. And, as the systems we design only grow more rooted in culture, I’m convinced we must dig deeper into ethnography.

Second, as an outside consultant, I must understand the culture of the organizations for which I work. Today’s systems aren’t only integral to the lives of users, but they are progressively part of the way we do business. To improve user experience, it may be necessary to change the org chart, metrics, incentives, processes, rules, and relationships. Connections and consequences run all the way from code to culture. Software that doesn’t work “the way we work” will fail like an employee who doesn’t fit. So we must also study and design for stakeholders. In my research, I always interview a mix of executives and employees about roles, responsibilities, vision, and goals. And I’ve learned that if I don’t ask the right questions in the right way, or if I don’t listen carefully and read between the lines, I may mistake the surface for substance and invent a design that won’t fit.

Figure 4-1. We must design for a bi-cultural fit.

In short, the right design is one that fits the company and its customers. A mismatch on either side results in fatal error. We must use ethnography with our users and stakeholders to search for a bi-cultural fit. This is tricky since culture is mostly invisible. That’s why we should start with a map.

Mapping Culture

Edgar Schein, professor emeritus at MIT and the father of the study of corporate culture, offers a useful definition.

Culture is a pattern of shared tacit assumptions that was learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.xciii

Culture is a powerful, often unconscious set of forces that shape both our individual and collective behavior. In an organization, culture is reflected in “the way we do things here.” It influences goals, governance, strategy, planning, hiring, metrics, management, status, and rewards.

And culture is an artifact of history. Organizational culture is rooted in the values of the entrepreneur. In the early days, as leaders struggle to build the business, the beliefs and behaviors that lead to success are internalized. Eventually they become taken for granted, invisible, and non-negotiable.

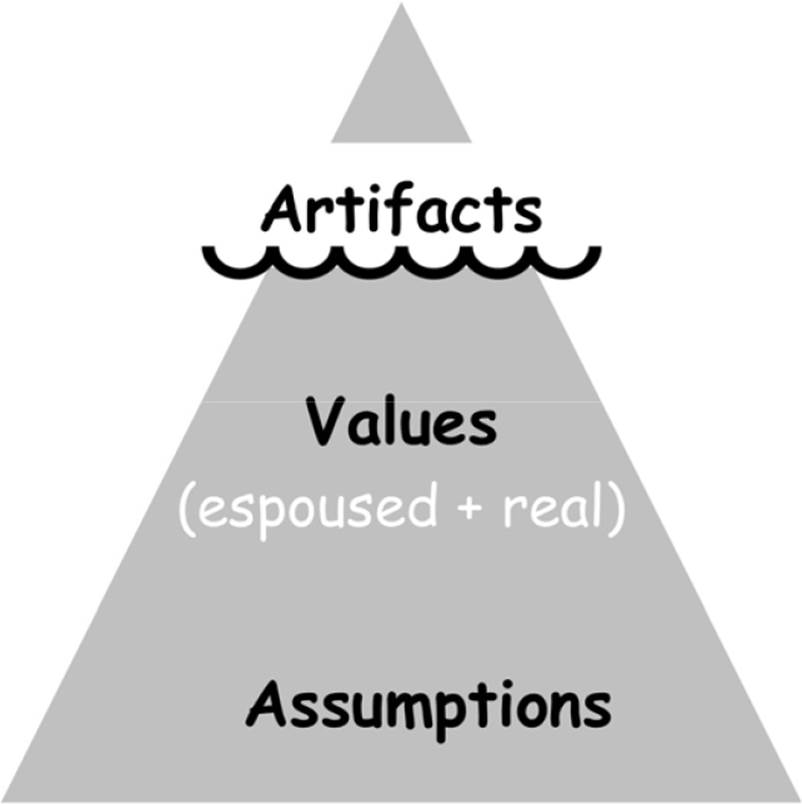

At this point, it’s difficult to decipher the culture without a compass or map. Fortunately, Edgar Schein’s model offers the orientation we need. We can use his Three Levels of Culture to ask questions about any institution.

Figure 4-2. Three levels of culture.

First, what will a visitor see, hear, and feel? Artifacts include architecture, interior design and layout, technology, process, work style, social interactions, and meetings. Who’s the boss? How can you tell? Is there music? Are people talking? What do they wear? Where do they sit? When do they eat? What makes ‘em smile? Artifacts are easy to see but hard to decode. The art on the wall is visible but what does it mean? Why’s it there? Artifacts aren’t answers, but they raise good questions.

Second, what are the mission, vision, and values? How about goals, strategy, brand? Websites, annual reports, and those colorful posters so artfully framed in the lobby offer a place to start, but interviews with insiders are the only way to the truth. Espoused values are hard to miss yet often inconsistent with behavior, which is why we need “informants” to help us see what’s really going on. If teamwork is a core value, why are individuals so competitive? If the organization is user-centered, why doesn’t anyone talk to users? It’s vital to listen carefully as insiders may not know or be willing to tell the truth. Dissonance and its justifications serve as keys to the invisible culture. Entry is earned by paying attention.

Third, what are the tacit beliefs that are taken for granted and non-negotiable? Level three is all about history. What were the ways of the founders that led to success? Are they still valid or holding us back? When we fail to seize the future, it’s often because we’re blinded to the present by the radiance of our past success. Assumptions are the bedrock of culture. They are hidden and resistant to change. As organizations grow, technologies advance, and markets evolve, friction between old assumptions and new realities is inevitable, but people don’t question what they can’t see. This is where an advisor can help. Only insiders can effect cultural change, but it often takes an outsider to sketch the map.

Subcultures

No culture is an island. To understand any culture, we must study its context. For example, Ed Schein notes that “in some organizations the subcultures are as strong or stronger than the overall organizational culture.”xciv It may be useful to think of them as “co-cultures” to avoid false assumptions about influence and power. To succeed we must employ multiple levels of analysis and seek leverage in the layer that counts.

A few years ago, I was asked to evaluate site search for one of the world’s largest technology firms. The problems were painfully obvious. Customer satisfaction surveys showed findability to be the #1 complaint. Search analytics data revealed a zero click-through rate of forty-eight percent. In nearly half of all queries, users failed to click on a single result. And in my user research, I saw people fail to find basic content, over and over again. One customer summed up the search results interface by stating “There’s a lot of garbage here. And the filters are all gobbledygook.”

I was excited by this opportunity to make search better, but I soon hit a roadblock. As I led stakeholder interviews, a pattern emerged. The folks in Support were eager to fix site search, but those in Marketing weren’t very interested. Most of them were too polite to say it straight, but it wasn’t hard to read between the lines. They were enthusiastic about search engine optimization as it offered new customers and easy metrics, but site search didn’t fit their sense of mission. They didn’t study it in business school. This was a major problem, as Marketing owned the website and held all the money and power.

So, I worked with my clients in Support to craft a message that would resonate with the people in Marketing. We used data, told stories, and invoked experts. Here’s an excerpt.

Gerry McGovern argues that “Support is the new Marketing.” This hints at the emerging tendency of customers to evaluate a company’s online support as part of the pre-purchase process. Our prospective customers and partners are smart. They know that Support is a vital component of the total cost of ownership. If they can’t find what they need quickly, they lose time and business. Also, we can help users become aware of related products and services while seeking support. If done in a user-centered manner, this cross-sell and up-sell can be a win-win-win for us, our partners, and our customers…Mark Hurst says “the experience is the brand.” He’s acknowledging the tectonic shift from push to pull that’s driven by the Internet. While names, logos, prices, packaging, and product quality are all still contributors to the brand, people’s perceptions are increasingly shaped by their experiences with the website. When customers can’t find what they need, the brand suffers. In an era of user-centered design, where expectations are shaped by positive experiences with consumer sites from Amazon to Zappos, it’s clear that the sad state of site search is damaging and merits further attention and investment.

We asked customers to solve problems using the site, and captured video footage so stakeholders could see, feel, and share their frustration. We also appealed to the original source of the organization’s success, the culture of Engineering, noting the potential of a slow, broken search system to embarrass a technology firm known for its software and hardware. Finally, we delivered a blueprint and a roadmap. We inspired confidence that these difficult problems could be solved. And it worked. We spoke the language of their culture, and they listened. Together we made search better.

Of course, when it comes to co-cultures, there are some things you just can’t fix. I saw this firsthand while working with DaimlerChrylser soon after the 1998 merger. We were hired to build an information architecture strategy for a unified corporate portal. By integrating several American and German intranets into a single source of truth, executives hoped to bring the cultures together. While this seemed unrealistic, we were willing to give it a go. But the more we learned, the less we believed in the mission. In stakeholder interviews, the absence of trust was palpable.

This was a culture clash of epic proportions. On the surface, friction was caused by different wage structures, org charts, values, and brands. But at a deeper level, conflict was driven by differences in national culture. The entrepreneurial frontier spirit and individualism of the Americans did not fit with the methodical, risk-averse, team-oriented, bureaucratic culture of the Germans. At the time, we didn’t understand all the forces at work, but we knew the unified portal would never happen. Of course, that was the least of their worries. Eventually the failed merger resulted in a market loss of over $30 billion. Nowadays people agree it didn’t fail because the strategy was unsound. It’s a deal that was killed by culture.

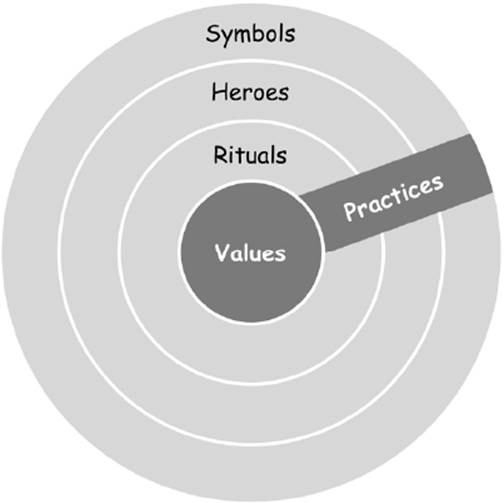

This story serves as a reminder that corporate culture is rooted in the national culture in which an organization operates. This brings us to the work of Geert Hofstede, a pioneer of cross-cultural research, who offers us an onion as a metaphor for understanding the cultures of countries.xcv

Figure 4-3. The Cultural Onion.

Symbols are words, images, objects, and gestures with special meaning to those in the culture. Heroes are people, alive or dead, real or imaginary, who exhibit role model qualities. Rituals are activities that are technically superfluous but socially essential, like how we say please and thank you. All three can be seen as practices and are visible to the outside observer. The hidden core is formed by values, defined as “broad tendencies to prefer certain states of affairs over others.”xcvi Our feelings about good and evil, danger, beauty, and nature are values, and they’re acquired in childhood. Practices come later. They are learned at school and work.

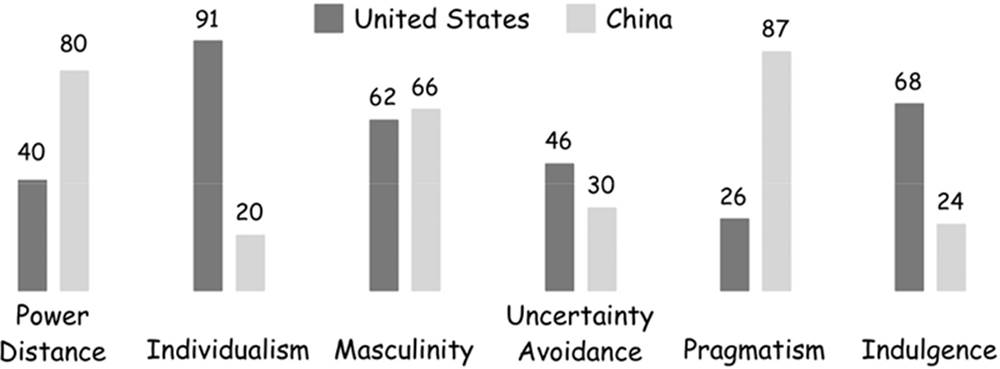

In a heroic effort to make the invisible visible, Geert Hofstede led a multi-national, multi-decade research program to study cultural differences. He concluded that six dimensions – power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, pragmatism, and indulgence – offer insight into what makes us tick differently. Let’s take a look by comparing two countries.

Power distance describes the degree to which members of society accept and expect the unequal distribution of power. In the United States where “all men are created equal,” the score is low relative to China where formal authority, hierarchy, and inequality require no justification. As inequality continues to rise in the U.S. we can expect cultural resistance.

Figure 4-4. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions.

Individualism measures interdependence among members. The U.S. is the most individualist society in the world. People are expected to look after themselves and their direct family. In contrast, China is collectivist with an emphasis less on “I” than “we.” People belong to “in-groups” that take care of them in return for loyalty and preferential treatment.

Masculine cultures are driven by competition, assertiveness, and material success, whereas feminine societies like Sweden and Norway value cooperation, modesty, caring for the weak, and quality of life. Both the U.S. and China are masculine. In masculine societies, homosexuality is seen as a threat, and the label of this dimension is politically incorrect.

In an uncertainty avoidance culture like Japan, plans and rituals are used to manage risk, ambiguity, and fear of the unknown future. The U.S. and China score low. Both are open to new ideas, practices, and technologies.

Pragmatism is about how we relate to our inability to explain the world. In the normative U.S. people seek absolute Truth in science, religion, and politics, and we evaluate performance using simple, short-term metrics. In pragmatic China, the truth depends on context, traditions can be changed, thriftiness is admirable, and the long term is really what counts.

Indulgence measures the degree to which people control their desires. In a restrained society such as China, people adhere to strict social norms, tend to be cynical, and hold a low view of leisure. In the indulgent U.S. we’re fairly free to gratify natural drives by enjoying life and having fun.

Geert Hofstede argues these values are built atop national paradigms – China (family), Germany (order), Britain (systems), U.S. (markets) – and that together they interact to shape the unique culture of each country. Also, he asks us to consider relationships between cultures at multiple levels.

National value systems should be considered given facts, as hard as a country’s geographical position or its weather. Layers of culture acquired later in life tend to be more changeable. This is the case, in particular, for organizational cultures, which the organization’s members joined as adults. It doesn’t mean that changing organizational culture is easy, but at least it is feasible.xcvii

Our beliefs and behaviors emerge from interactions between the cultures of nations, organizations, communities, families; and the forces of individual personality and human nature. It’s not worth trying to draw clear boundaries. Instead, we should aim for a rough map of the relevant co-cultures and contexts in which they exist. A deep dive into culture reveals “turtles all the way down,” but that’s no reason to give up. Between perfect vision and total blindness lies all the truth we know.

Ways of Knowing

Brigitte Jordan, the legendary corporate anthropologist and beloved godmother of design ethnography, made a mark early in her career with a brilliant series of cross-cultural studies of childbirth. In one, conducted in a U.S. city hospital in the 1980s, she used video, medical records, and postpartum interviews to explore and describe the culture of obstetrics.

The people present in the labor room with the woman are her husband and a nurse…The husband appears intimidated…The nurse is in a delicate position…she needs to assess the woman’s state within a small range of error in order to be able to call the physician in time for the crucial stages of delivery that require his presence, but not so early as to waste his valuable time…she is very much preoccupied with the electronic fetal monitor (EFM)…even though it has never been shown that routine EFM treatment improves birth outcome…The woman is not allowed to push. Every effort is made to keep her from giving in to the overpowering impulse to bear down. She is asked to suppress the urge long enough for the physician to come in and pronounce her ready. The physician is paged several times but does not appear…The physician finally arrives, together with a male medical student. He examines the woman and declares she is ready to push. The staff prepare her for delivery…The child is delivered by the medical student who announces it’s a boy…Finally, several minutes after the baby is born, he is given to his mother to hold. xcviii

In the half hour before the baby is born, the woman “knows she has to push and says so clearly.” The nurse largely ignores the woman’s body and voice but repeatedly checks the EFM (19 times in 5 minutes). When the doctor enters the room, he doesn’t talk to the woman, and after making his decision, he says “she can push” and the nurse relays the message.

Throughout the labor, participants work hard to maintain the definition of the situation as one where the woman’s knowledge counts for nothing. They all know she “cannot” push until the doctor gives the official go-ahead. Within this particular knowledge system, it is believed that only the doctor can tell when a woman is ready to push – information he gains from checking the dilation of the cervix during a vaginal examination. This fiction is maintained collaboratively, by the woman herself, her husband, the nurse, the medical student – in the face of the fact that anybody who cares to look or listen can see that this woman’s body is ready to push the baby out…However, what the woman knows and displays, by virtue of her bodily experience, has no status.

In short, the woman is treated as an object, and the doctor is in charge of the facts. Jordan uses this powerful ethnography to illustrate the concept of “authoritative knowledge.”

Within any social situation a multitude of ways of knowing exist, but some carry more weight than others. Some kinds of knowledge become discredited and devalued, while others become socially sanctioned, consequential, even “official,” and are accepted as grounds for legitimate inference and action…The legitimation of one way of knowing as authoritative devalues, often totally dismisses, all other ways of knowing…The constitution of authoritative knowledge is an ongoing social process that both builds and reflects power relationships within a community of practice…The power of authoritative knowledge is not that it is correct but that it counts.

To be fair, we may rely on hierarchical decision-making for good reason, but authoritative knowledge is driven by both efficacy and power. So it’s naïve to inquire which way is better. Better for whom? Better in which contexts? Better for what purposes? These are the questions we must ask.

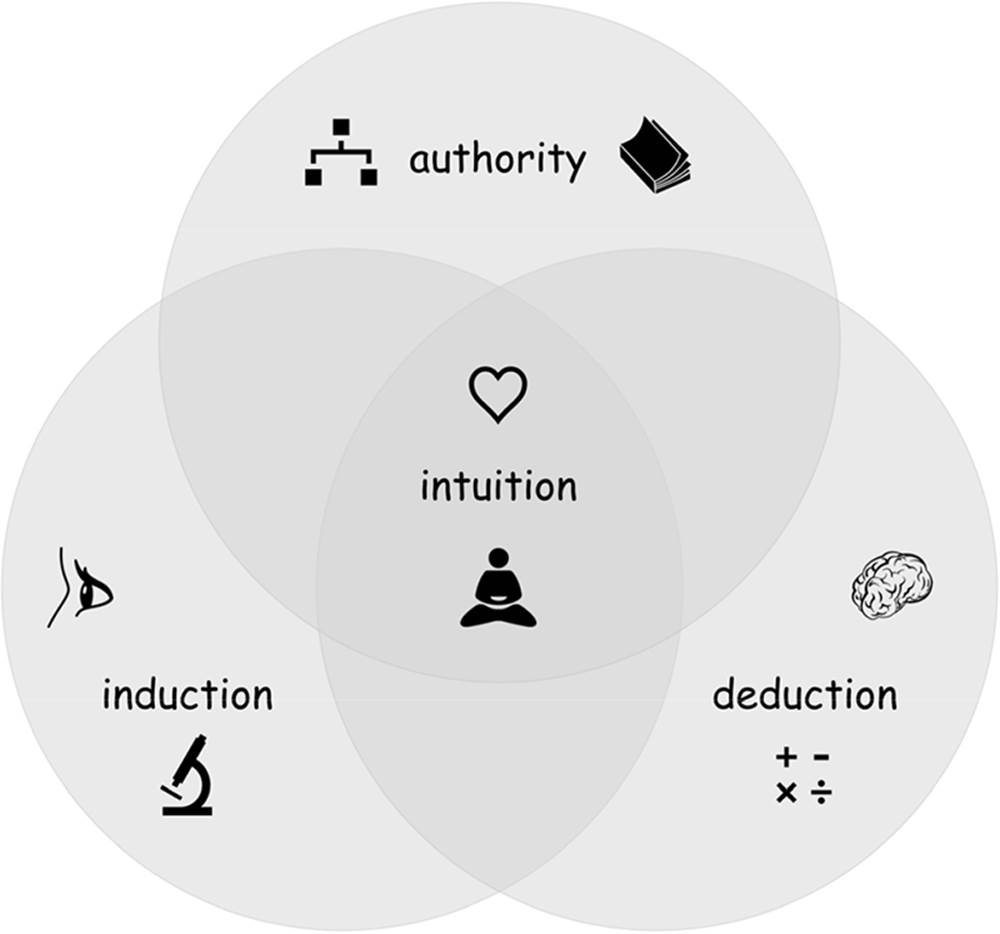

Not so long ago, our ways of knowing were different. Before the printing press, we relied heavily upon personal experience and our senses, using evidence and induction to find the truth. In time, we extended our senses with instruments and formalized trial-and-error as the scientific method. We added to our empirical ways with deduction, using reason and logic to mathematically prove the truth. To absorb second-hand knowledge, we had to do it in person. Cultural wisdom was embodied in rituals, habits, laws, and myths. Power, authority, and trust were centered in the community.

Today most knowledge is second-hand, and we don’t even know where it comes from. Access to massive amounts of conflicting information from myriad sources creates filter failure. We don’t know what to believe. So we fall back on simple ways of knowing. We trust experts and those in authority. We follow doctor’s orders. Or we reject expertise completely. Like U.S. senator James Inhofe, we know global warming is a hoax, because it’s cold outside. Of course, we’re not forced to a single extreme. We may allow for many inputs, and then use intuition to feel our way to the truth.

Figure 4-5. Ways of knowing.

We do this often in our personal lives, but it’s tricky to pull off in business. It’s hard to ask others to “trust my gut” so we routinely manufacture evidence. Experts are hired to validate the course of action. User studies are designed to approve the interface. Metrics are defined to back the plan. It’s amazing how much is done in support of what we already know.

Within a culture, the idiosyncrasy of authoritative information is mostly invisible. Insiders rarely question their institutional ways of knowing. As a consultant, I’ve had clients who place too much faith in my expertise, and others who don’t trust enough. Some use “usability tests” as the sole source of truth. Others track conversions as the way to know what’s right. And an awful lot of folks simply believe the boss knows best.

As an outsider, it’s my role to ask the questions that never get asked, but when I begin I have no idea what they are or where to find them. So I use a multi-method research process that affords breadth and depth. I wallow in data of all sorts and talk to people from all walks. While I begin with observation and analysis, I’m aiming for insight and synthesis. Towards this end, I find lightweight forms of ethnography to be great tools for digging into the cultures of users and stakeholders.

Design Ethnography

Unsurprisingly, Clifford Geertz, the eminent pioneer of symbolic anthropology, defines culture metaphorically.

Believing, with Max Weber, that man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be those webs, and the analysis of it to be not an experimental science in search of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning.xcix

Ethnography is how we discover and describe this meaning, and Geertz argues it isn’t defined by a methodology but by a particular way of knowing. “What defines it is the kind of intellectual effort it is: an elaborate venture in, to borrow a notion from Gilbert Ryle, thick description.”c

A thin description of the superficial behavior that’s easily accessible via observation misses the point. In the contraction of an eyelid lies the vast distance between an involuntary twitch and a conspiratorial wink. The ethnographer needs to understand the meaning behind the behavior.

In The Ethnographic Interview, James Spradley offers a thick description of the art of thick description. He sees words as keys to culture, noting “language is more than a means of communication about reality: it is a tool for constructing reality.”ci He enjoins ethnographers to pay attention to the words we hear and use. For instance, the people we study and interview are informants, not subjects, respondents, or actors.

Ethnographers adopt a particular stance toward people with whom they work. By word and action, in subtle ways and direct statements, they say, “I want to understand the world from your point of view. I want to know what you know in the way you know it. I want to understand the meaning of your experience, to walk in your shoes, to feel things as you feel them, to explain things as you explain them. Will you become my teacher and help me understand?”cii

We must be careful how we ask questions. Spradley recounts his experiences studying the “homeless men” who turned out to be “tramps” noting that if you ask “where do you live?” they answer “I have no home.” They use translation competence or “the ability to translate the meanings of one culture into a form that is appropriate to another culture.”ciii They tell you what they think you want to hear in your language. But if you admit ignorance and ask descriptive questions (e.g., Tell me about a day in your life. Where do you sleep? Where do you eat? What do you do?) you may learn about “making a flop” and realize that they aren’t homeless after all.

I discovered that making a flop was such a rich phrase that I scarcely scratched the surface of its meaning. My informants identified more than a hundred different categories of flops. They had strategies for locating flops, for protecting themselves from the weather and intruders in flops. Making a flop defined their friendship patterns and even their police record…I realized that, in some ways, a flop was like a home to a tramp, but I did not merely translate the one term into the other for my ethnography. Instead I worked to elucidate the full meaning of this concept, to describe their culture in its own terms.civ

Ethnography is tricky since we aim to discover from our informants not just the answers but the questions as well. It’s all too easy to impose our assumptions on their culture. In observations and interviews, we should aim for what Zen Buddhists call “beginner’s mind” – an attitude of openness, awareness, and curiosity without beliefs or expectations. If we study high school students, for instance, instead of starting with specific questions about academics or athletics, we might say “If I sat at your table at lunch, what sorts of things might I hear?” This invites our informants to tell us about topics that are important to them in their own language.

Of course, perfect openness is neither possible nor desirable. As ethnographers, we seek insights to advance our goals. Spradley’s list of universal cultural themes serves as a good place to start. He suggests we look for social conflict, cultural contradictions, informal techniques of control (e.g., gossip, rewards), strategies for dealing with strangers, and ways of acquiring and maintaining status. Similarly, Hofstede offers an interview checklist, but his is aimed at corporate culture.

Symbols: What are the special terms that only insiders understand?

Heroes: What kinds of people advance quickly in their careers here? Whom do you consider as particularly meaningful persons for this organization?

Rituals: In what periodic meetings do you participate? How do people behave during those meetings? Which events are celebrated in this organization?

Values: What things do people like to see happening here? What is the biggest mistake one can make? What work problems can keep you awake at night? cv

And Edgar Schein tells us to “decipher the reward-and-status system. What kind of behavior is expected, and how do you know when you are doing the right or wrong thing?”cvi While pay increases and promotions do matter, less obvious forms of social currency may also be powerful.

Finally, as information architects, we may ask about the use of systems and services. What tools do you use, and why? Can you show me how you achieve that goal? What happens when this tool doesn’t work? Where you do go to find answers? How do you know who to trust? It appears we could ask questions all day, but as Spradley reminds us, we’re less interested in surface-level specifics than deep structure.

Cultural knowledge is more than random bits of information; [it] is organized into categories, all of which are systematically related to the entire culture.cvii

Culture is a system of symbols and relationships. Using domain analysis and taxonomy construction, ethnographers make maps that show how people have organized their knowledge. The first step is to describe the domain by identifying categories, connections, and boundaries.

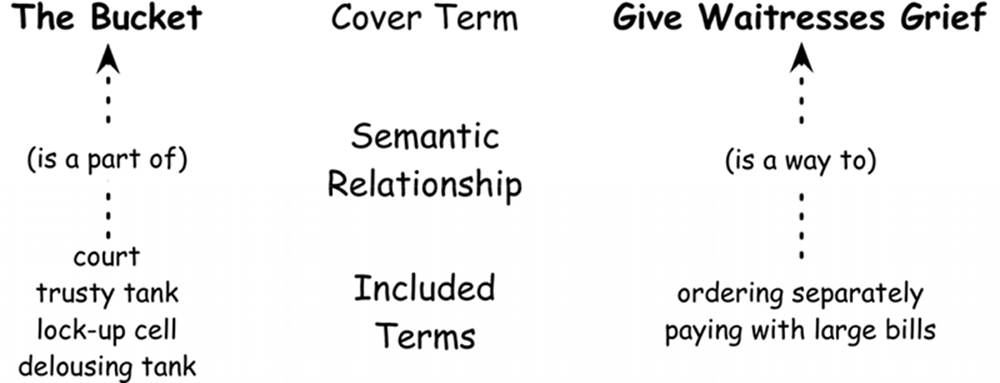

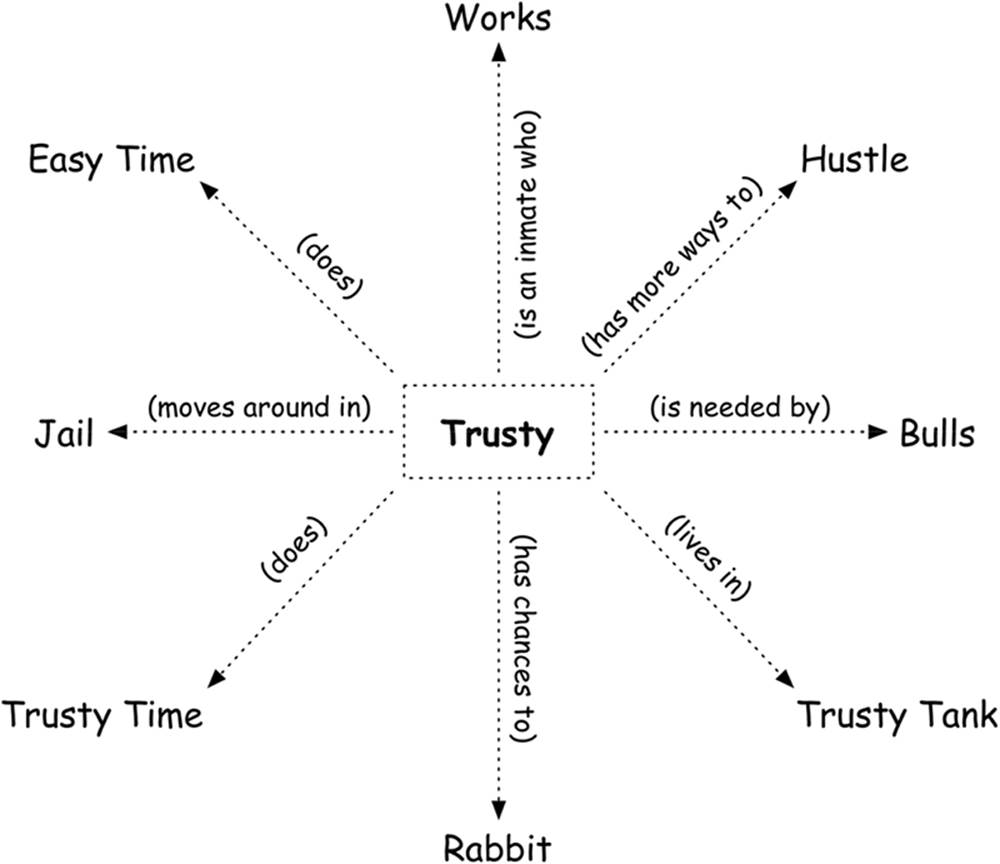

Figure 4-6. Elements in a domain.cviii

This domain analysis builds towards taxonomy construction and the mapping of attributes and semantic relationships.

Figure 4-7. Attributes and semantic relationships.cix

The folk taxonomy or “set of categories organized on the basis of a single semantic relationship” is the core. Analysis may reveal the attributes and relationships for each folk term.

Here, ethnography and information architecture are indistinguishable. Taxonomies are boundary objects used in many ways by many communities. But our practices diverge in their goals. An ethnographer’s work concludes with a “thick description” and the understanding of a culture, while the information architect aims to create or change a system.

So our approach to ethnography differs from that of an anthropologist. We have less time for field work, but that’s mitigated by more directed goals. Since we’re focused on interactions with systems and services, in addition to asking questions, we use sketches and prototypes to probe for possibility. We’re interested in what is and what if as well.

Levers of Change

Early in my career, I designed some fancy information architectures that were never built, and others that failed to stand the test of time. I had a freshly minted degree in library science and knew all sorts of ways to structure and organize information, but I didn’t realize the value of the right fit. My designs were technically elegant but culturally clumsy. I paid scant attention to silos, subcultures, and reward-and-status systems. My clients paid the price. On the bright side, they learned valuable lessons about change. In The Fifth Discipline, Peter Senge argues for systems thinking as the basis for learning organizations, and defines eleven laws, including:

The cure can be worse than the disease.

The harder you push, the harder the system pushes back.

The easy way out usually leads back in.cx

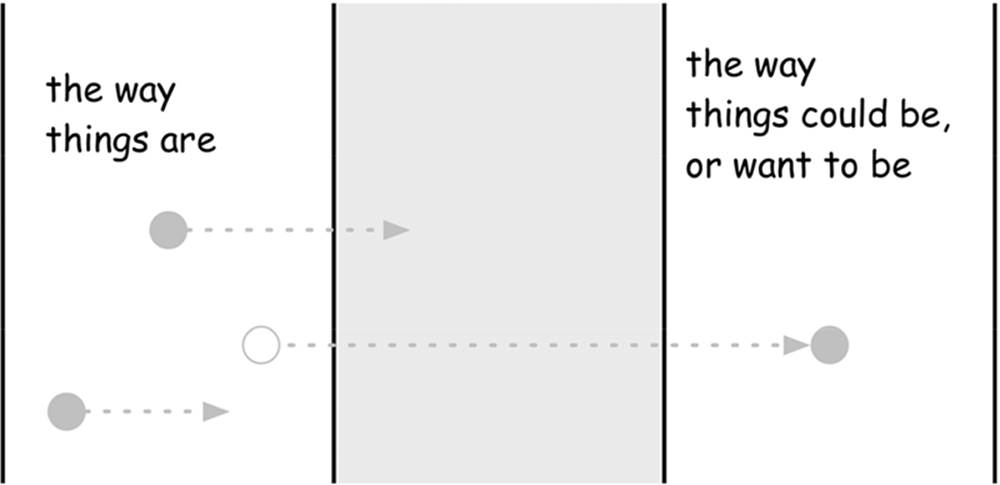

One of the most useful things I’ve learned in twenty years of consulting is that change is surprisingly difficult. Most interventions fail to stick. Organizations get all jazzed up about the way things could be only to revert to the way things are.

Figure 4-8. The power of organizational inertia.

This is discouraging, but lasting change is possible if we work to understand the source of inertia. As Peter Senge explains “Resistance is a response by the system, trying to maintain an implicit system goal. Until this goal is recognized, the change effort is doomed to failure.”cxi Senge also offers a word of encouragement. “Small changes can produce big results, but the areas of highest leverage are often the least obvious.”cxii

His insights capture my experience as an information architect precisely. In recent years, I’ve learned to search for a fit and to look for the levers. I aim to align my design with culture, and to the extent that a cultural shift is desirable, I look for sources of power while cultivating my own humility. My approach to intervention is inspired by the wisdom of Edgar Schein.

Culture is deep. If you treat it as a superficial phenomenon, if you assume that you can manipulate it and change it at will, you are sure to fail.cxiii

Schein warns us to “never start with the idea of changing a culture,”cxiv but to begin with business goals and enlist culture as an ally when possible.

Since culture is very difficult to change, focus most of your energy on identifying the assumptions that can help you. Try to see your culture as a positive force to be used, rather than a constraint to be overcome.cxv

To identify opportunities for cultural jujitsu, a multi-level approach is most useful. If our design invites resistance from the corporate culture, for instance, perhaps we can look to an organizational subculture or the national culture or human nature for support. Also, rather than limit ourselves to a single tactic, we must embrace multiple ways of changing.

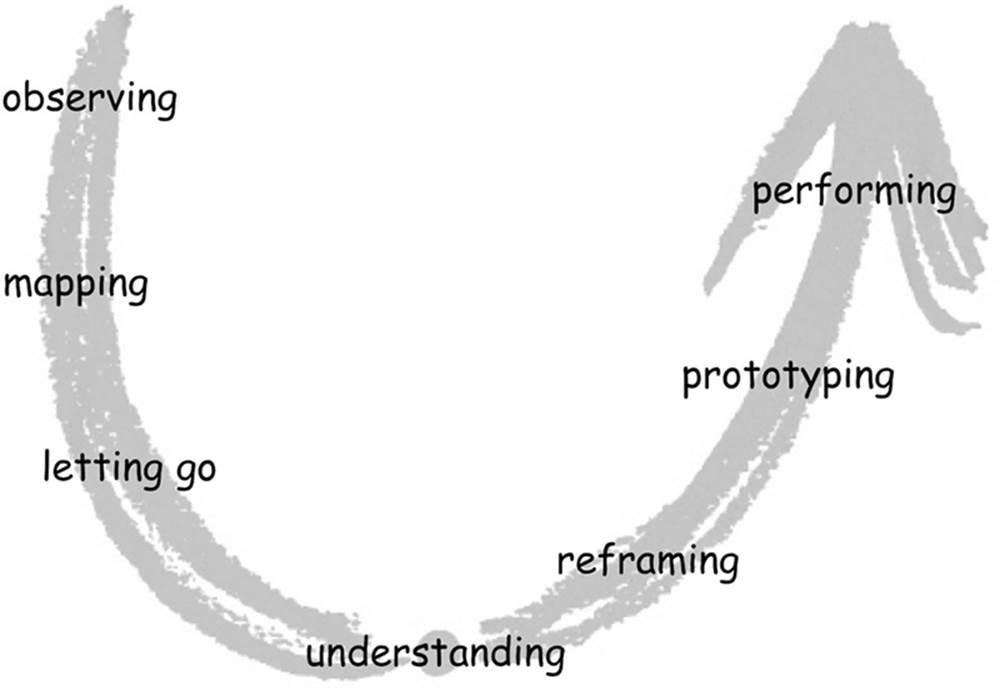

Figure 4-9. Multiple ways of changing.

Often, our first tactic for making change is information. To improve diets, we tell kids about the links between donuts, soda, obesity, and diabetes. To improve efficiency, we inform staff about new procedures or values. These educational interventions draw upon the power of authoritative information to change minds and behavior. While this tactic works well sometimes, it’s easily thwarted by established habits and assumptions. People tend to deny data that proves inconvenient truths unless the driving forces (burning platform, external threat, positive vision) are greater than the restraining forces (self-justification, fear of change, cultural inertia).

To offset defensiveness, we may need to guide folks through a U-shaped process that makes room for learning through unlearning. By observing the system and mapping the whole, we unfreeze beliefs and open minds. We help folks understand the context and consequences of their actions.

Figure 4-10. U-shaped learning.

As Otto Scharmer, a leading proponent of Theory U, explains:

The journey from ego-system to eco-system awareness or from “me” to “we” has three dimensions: (1) better relating to others; (2) better relating to the whole system; (3) better relating to oneself. These three dimensions require participants to explore the edges of the system and the self.cxvi

This is why ethnography is so vital to design. Personal interaction with users leads to insight and empathy. When we see customers struggling and suffering, we’re motivated to improve our systems. Often, to create change, information isn’t enough. People need to care about the outcome.

Relative to information, architecture is a less direct but more persuasive path to change. Of course, the two tactics usually work best when paired. For instance, asking designers and engineers to collaborate may have a limited effect, unless we also co-locate their desks. As Winston Churchill famously remarked “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

In Nudge, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein define a “choice architect” as a person responsible for “organizing the context in which people make decisions.”cxvii They note that by rearranging a school cafeteria, it’s possible to increase or decrease the consumption of many food items by as much as 25 percent.cxviii Of course the context need not be physical. In one study, forty thousand people were asked “Do you intend to buy a new car in the next six months?” The act of asking the question increased purchase rates by 35 percent.cxix In another study, changing a retirement plan from opt-in to opt-out bumped up long-term enrollment from 65 to 98 percent.cxx

The practice of information architecture has been all about nudging users by organizing context. We design taxonomies, order search results, and define all sorts of defaults to shape behavior by priming. Now, if we hope to create deep, enduring change, we must turn our rhetoric on ourselves. This is the hidden need Dave Gray has met with culture mapping.

In most large-scale organizational change projects, culture is the “elephant in the room.” It is not only undiscussed, it is undiscussable, at least in any serious, meaningful way. And yet it is the biggest threat to any major change.cxxi

To understand and change a culture, you must make the invisible visible, so Dave offers us a “Culture Map,” inspired by the work of Ed Schein, that asks a series of questions.

Evidence. How do we behave? What is observable (the language we use, the spaces we work in, how we collaborate, compete, create, control)?

Levers. What are the rules of the game that drive behavior (who controls what, decisions, resource allocation, rewards, workspace design)?

Values. What are the stated values (public statements)? How about the acted values (inferred from evidence, demonstrated by behavior)?

Assumptions. Based on acted values. Why do we believe they will help us succeed (or confer competitive advantage in our marketplace)?

These questions are designed to help us reveal and map the structure of a culture, since the first step towards change is awareness of the architecture that already exists.

A third means of change is direct intervention in the routine, unconscious behavior patterns we call habits. In The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg explores the science of habit formation and explains how to lose weight, achieve goals, and be more productive by hacking habits. He argues that “keystone habits” like exercise, diet, and family dinners can be fashioned into levers of change and used to start a chain reaction.

When you learn to force yourself to go to the gym or start your homework or eat a salad instead of a hamburger, part of what’s happening is that you’re changing how you think. People get better at regulating their impulses. They learn how to distract themselves from temptations. And once you’ve got into that willpower groove, your brain is practiced at helping you focus on a goal.cxxii

We need not change our habits all at once. In fact, it’s best to start small. As B.J. Fogg, the inventor of Tiny Habits, explains:

The number one mistake people make is not going tiny enough. If you’re trying to make a change in your life, you need to add something to your routine that is smaller than small, smaller than tiny, something minuscule, that takes almost no effort or time. This eliminates not only running as a new habit, but also running around the block or running down the driveway. Just put on your running shoes. That’s it. Put them on in the morning every day for five days. You’re done. Push-ups? You don’t do 10 push-ups. You do one. Flossing? You don’t floss your teeth. You floss one tooth.cxxiii

At first this sounds absurd. One tooth? Seriously? But there’s a method to Fogg’s madness. He asks people to practice their tiny habits in a particular way. A habit must require little effort, take less than 30 seconds, and be done at least once a day. The habit must be preceded by an anchor, an existing habit or event that triggers the new behavior. And the tiny habit must be followed by a reward or self-celebration. So, for instance, you may decide that “After I brush my teeth, I’ll floss one tooth, then shout Victory!”

Figure 4-11. The architecture of tiny habits.

Tiny habits are the building blocks of behavior. Fogg’s method makes the architecture of behavior visible, so we can see how to change what we do. After working with 10,000 people, he has proven that if you start small and take it one step at a time, you’ll see that tiny habits really add up.

Habits can be practiced not only by individuals but by teams as well, as this anecdote by Clay Shirky reveals.

Every now and again, I see a business doing something so sensible and so radical at the same time that I realize I’m seeing a little piece of the future. I had that feeling last week, after visiting my friend Scott Heiferman at Meetup. On my way out after a meeting, Scott pulled me into a room by the elevators, where a couple of product people were watching a live webcam feed of someone using Meetup. Said user was having a hard time figuring out a new feature, and the product people, riveted, were taking notes. It was the simplest setup I’d ever seen for user feedback, and I asked Scott how often they did that sort of thing. “Every day” came the reply.cxxiv

In most businesses, user research is sporadic, and only a few specialists participate in direct observation. But it’s not very difficult or expensive to create a setup that lets people who build systems watch people use those systems on a routine basis. Imagine how much better our systems and services might be if more teams made user research a regular habit.

Of course, cultural change must come from the top, but even with strong leadership, it’s hard to move the needle. Charles Duhigg tells the story of Paul O’Neil who set out to change the keystone habits of worker safety at Alcoa. In his first speech as CEO, he surprised his audience of investors and analysts.

I want to talk to you about worker safety. Every year, numerous Alcoa workers are injured so badly they miss a day of work. Our safety record is better than the general American workforce, especially considering that our employees work with metals that are 1500 degrees and machines that can rip a man’s arm off. But it’s not good enough. I intend to make Alcoa the safest company in America. I intend to go for zero injuries.cxxv

The audience was confused. Usually, new CEOs explained how they would lower costs, avoid taxes, and boost profits, but O’Neil talked only about safety. After the speech, financial advisors told clients to dump the stock. And initially, employees didn’t get on board either. They had all learned not to trust the words of executives. Then, six months into his tenure, O’Neil got a call in the middle of the night. A new hire had been killed while repairing a machine. The next day, after due diligence, O’Neil gathered all the plant executives and Alcoa’s top officers, and he gave another speech.

We killed this man. It’s my failure of leadership. I caused his death. And it’s the failure of all of you in the chain of command. cxxvi

O’Neil assumed responsibility for the incident and presented a plan to make sure it never happened again. He invited people of all ranks to contact him directly about safety, and when they did, he made sure the problems got fixed. Employees began to believe in the mission, and the culture steadily transformed. Soon Alcoa became the safest company in America. And its profits and market capitalization hit record highs. Safety turned out to be a keystone habit that started a chain reaction, but it took an act of leadership to write the story that made the people believe.

The folk singer and activist Pete Seeger is another leader who knew how to walk the talk. He didn’t just sing in support of freedom. In 1955, when subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Seeger refused to answer their questions and was cited for contempt and sentenced to a year in jail. And he didn’t just preach environmentalism but lived it, as the blues guitarist Guy Davis recalls in a story.

We were driving back from Amherst to an afternoon gig in Poughkeepsie. We had an hour to kill. We took a rest at this little walkway mall to take a nap, and we leaned our backs against a fountain. It was about ten feet in diameter with a brick wall. I closed my eyes and fell asleep. The next thing I know, I heard some splashing. I opened my eyes up, turned around, there’s Pete with his pants rolled up in the water picking the garbage out of the fountain, and he’s got these kids helping him, and I said to myself “this man is no hypocrite.”cxxvii

There’s a similar story about the Ann Arbor District Library. The director, Josie Parker, assumed leadership in the wake of a scandal. The former finance director had been found guilty of fraud. To regain the trust of the community, Josie set out to build “a culture of generosity.” In time, her efforts became visible on all levels, from the forgiveness of fines to construction of new branch libraries which are among the most beautiful buildings in town. One day, during the holiday season, Josie was volunteering at a bookstore, wrapping gifts to raise money for charity. People had been generous that day, and the donation jar was filled with dollars and change. Suddenly a man grabbed the jar and ran for the door. Josie chased and tackled him, fracturing her leg in the process. The thief escaped empty-handed, and the story made national news with a headline of “the librarian who saved Christmas.”

Each of these three leaders embodied their values and inspired people to tell their story. A compelling vision isn’t enough. Actions and words must fit. We withhold belief in the absence of behavior. But since only a few may witness the original act, it must be sufficiently interesting to be shared widely. In short, to change a culture, you must change the story.

We’ve examined four ways of changing – information, architecture, behavior, leadership – while saving the best for last. Synthesis is how we combine these elements into a holistic plan. None of them stands alone. One way is the wrong way to change culture. To overcome resistance, we must engage on multiple fronts. Marc Rettig offers a model for parallel thinking which builds upon William Gibson’s insight that “The future exists today. It’s just unevenly distributed.” Rettig tells us to identify the seeds around us that hold the promise of a better tomorrow.cxxviii If we show progress on multiple fronts by nurturing seeds into sprouts and helping people connect the dots, we can create momentum for change.

Figure 4-12. Marc Rettig’s seeds and sprouts.

In the 1990s, researchers proved the efficacy of this sort of approach by applying the concept of “positive deviance” to the stubborn problem of malnutrition in Vietnam. First, they enlisted villagers to help identify unusually well-nourished children. Then, using ethnographic methods, they learned these families were collecting foods considered inappropriate for children (sweet potato greens, shrimp, crab). Also, contrary to cultural norms, these “positive deviants” were feeding their kids three to four times a day, and washing their hands before and after each meal. A nutrition program based on these insights was created, and it worked. In two years, malnutrition fell by 85 percent. As the researchers explain, the approach leads to success because it starts with locally grown seeds.

Positive deviant behavior is an uncommon practice that confers advantage to the people who practice it compared with the rest of the community. Such behaviors are likely to be affordable, acceptable, and sustainable as they are already practiced by at risk people, they do not conflict with local culture, and they work. cxxix

I’m reminded of a project for Hewlett-Packard in which we discovered an example of positive deviance. We were asked to redesign the information architecture of the @hp employee portal. The existing system was the end result of a centralized, top-down redesign that failed to meet the needs of employees. The plan was to fix it with a centralized, top-down redesign. During our research, we stumbled upon a brilliant annotated index. Built and maintained by and for the administrative staff of HP Labs, it boasted an organized, curated list of contacts, links, and instructions. It was an unofficial, under the radar, totally awesome guide for getting things done. We held it up as an example of the decentralized, bottom-up tools that employees should be encouraged to create in order to complement the top-down structures we’d been asked to design. Sadly, there wasn’t much interest. In 2001, executives weren’t marching the HP way. But the idea was solid. Small wins, like an annotated index, are the right place to start.

Alone, each small win stands a good chance of making it past the cultural immune system. Together, multiple small wins create a visible pattern of progress. V.S. Ramachandran explains that “Culture consists of massive collections of complex skills and knowledge which are transferred from person to person through two core mediums, language and imitation.”cxxx We can use this monkey see, monkey do proclivity to our advantage. Once people perceive a trend, they are infinitely more likely to adopt a new tool, process, belief, or value. Under certain conditions, after passing the proverbial tipping point, a culture can change shockingly fast.

So, culture is not an immovable object. If we use multiple ways of changing in concert, we may be able to move the needle. But we must be ready for curveballs, since people make complex systems even less predictable. For instance, five years ago, I went bald. I mean, it had been going on for a while, but one day I finished the job. My wife was out, so I showed our daughters first. “Claire, I have a surprise for you,” I called, and our ten year old walked into the room. She then screamed, ran to the corner, curled into a fetal ball, and cried and cried and cried. I hugged her and told her it was okay, and then I cheered her up by suggesting we surprise her eight year old sister. But when we found Claudia, she surprised us instead, by staring me in the face and asking “what’s the big surprise?”

When we change, some people totally freak out, while others don’t notice or care, and it’s only after you act that you understand who will do what. When Claire played for the maize and blue volleyball club, she and her teammates were unhappy with the way the coach ran practices. The girls were too scared to speak up, but I encouraged Claire to talk to her coach. The meeting went badly. The coach behaved defensively. She expected the players to accept her authority without question, but that’s not the way we raise our girls, so the confrontation escalated, and the next gameClaire was benched. It was a painful but useful lesson, and an illustration of Brigitte Jordan’s insight that “the power of authoritative knowledge is not that it is correct but that it counts.” Claire learned that in some cultures and contexts, it’s best to keep your mouth shut, and escape as soon as you can.

As an information architect, I think about change on two levels. First, I identify opportunities for improvement that fit my client’s culture. Once I’ve uncovered the problem and described a solution, these technical fixes become low-hanging fruit. Second, I explore innovative ways to improve the user experience that may be obstructed by the organizational culture. In this quest, I proceed very carefully. If I believe that change is possible, and if the cause is worth it, I may push hard. In the words of Brenda Laurel, I’ll try “inserting new material into the cultural organism without activating its immune system.”cxxxi Otherwise, I’ll tactfully tell my client of the cultural constraints, and let them decide whether to act.

Experience teaches us that change is hard. Often we opt for the serenity of Paul McCartney’s Let It Be. But once in a while we summon the courage to change the things we think we can. It doesn’t always work out. Mostly we lack the wisdom to know the difference. Time and again, we don’t know our own limits.