The Resilient Investor (2015)

CHAPTER 2

More Than Money: Recognizing Your Real Net Worth

Personal, Tangible, and Financial Assets

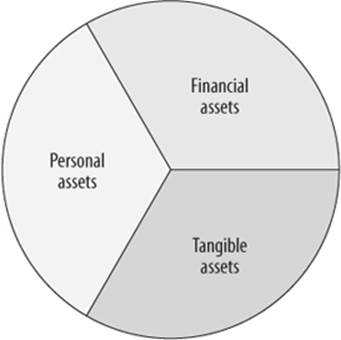

THE RESILIENT INVESTING MAP INVITES YOU TO INVEST IN YOUR LIFE in a way that recognizes and grows all of your assets. Indeed the goal of resilient investing is to consciously and methodically spread your time and money around the full RIM to nourish all the elements of your complete “net worth.” This will include prudence with your money (financial assets), appreciation of your possessions and the built and natural world (tangible assets), and nourishing your relationships and inner growth (personal assets). SEE FIGURE 2

It may feel a little strange to think of, say, the ways you prioritize activities that enhance your child’s well-being and the strategies you are using to manage a brokerage account as being parts of a unified investment system. We’re trained to think of these as very different kinds of decisions, but they are indeed related, as both are investments you make to bring about a desired result in the future.

Resilient investing enables you to put all of your goals on the table as you consider where you want to direct your time, attention, and money. Crucially, this approach acknowledges that for most people financial resources are limited. Those who cannot set aside money to invest should realize that they are indeed making investment decisions that are just as important—maybe more so—than those who are fortunate enough to have a brokerage account. At the same time, by looking beyond financial investments, we encourage everyone to diversify their investment horizons to include the equally important tangible and personal realms. The ways you engage and are nourished by your home and your ecosystem, and the crucial roles of your loved ones and the pursuit of your dreams, are at least as important as your portfolio balance.

Figure 2 Your Real Net Worth

Let’s take a closer look at your real net worth by taking a ramble along the rows of the RIM.

Financial Assets

Financial assets, the bottom row of the RIM, are the familiar currency of the realm that we are used to calling “investments.” This may include corporate stocks, debt instruments (i.e., bonds) that loan money to governments or corporations, and your short-term savings and checking accounts. Mutual funds, and now exchange-traded funds (ETFs), were created to help ordinary investors diversify their holdings of stocks and bonds. Wall Street also offers more complex instruments, ranging from relatively simple options contracts to a bewildering array of derivatives and bundled risk instruments that most of us, professionals included, would be stretched to comprehend (which is how their creators like it!). Those who have substantial assets or higher incomes may access the world of private investments and hedge funds.

Financial assets, the bottom row of the RIM, are the familiar currency of the realm that we are used to calling “investments.” This may include corporate stocks, debt instruments (i.e., bonds) that loan money to governments or corporations, and your short-term savings and checking accounts. Mutual funds, and now exchange-traded funds (ETFs), were created to help ordinary investors diversify their holdings of stocks and bonds. Wall Street also offers more complex instruments, ranging from relatively simple options contracts to a bewildering array of derivatives and bundled risk instruments that most of us, professionals included, would be stretched to comprehend (which is how their creators like it!). Those who have substantial assets or higher incomes may access the world of private investments and hedge funds.

For those who seek a “triple bottom line” (social, environmental, and financial), it has long been possible to select financial assets that align with one’s personal values.1 Most of the above choices are available through sustainable and responsible investing (SRI), and performance has been reliably competitive (see Resource 1: The Case for SRI). In recent years community investing has created many opportunities to bank locally as well as to put some savings into community loan funds that do great work. Opportunities to participate in microfinance in the developing world or to loan your money to programs supporting local food systems are increasing every year, while qualified investors can choose among a wide range of private placement offerings in social enterprises that serve sectors such as education, healthcare, renewable energy, green development, and sustainable agriculture and forestry.

Crowdfunding is one of the newest innovations, enabling people to directly support startup companies and arts, social change, or environmental projects; though not fully implemented as of this writing, legislation passed in 2012 is designed to allow small investors (as opposed to high-net-worth investors, who already have this right) to make modest investments in companies that are just getting started or that wish to expand. It holds great promise for individuals who wish to invest locally and for small businesses that can now access the capital markets.

Tangible Assets

Tangible assets are the “stuff” that we own or have access to; these occupy the middle row of the RIM. Most important are the practical aspects of daily life on which our survival and happiness depend: food, water, clothing, energy, land, buildings, transportation, and technology. Whenever we trade our time, energy, or money for anything physical—whether we hold it personally, like a well-forged shovel, or collectively, like a shared summer cabin—it becomes one of our tangible assets. It is easy to overlook this realm when thinking of our investments, especially those that are not “liquid,” or readily resold.

Tangible assets are the “stuff” that we own or have access to; these occupy the middle row of the RIM. Most important are the practical aspects of daily life on which our survival and happiness depend: food, water, clothing, energy, land, buildings, transportation, and technology. Whenever we trade our time, energy, or money for anything physical—whether we hold it personally, like a well-forged shovel, or collectively, like a shared summer cabin—it becomes one of our tangible assets. It is easy to overlook this realm when thinking of our investments, especially those that are not “liquid,” or readily resold.

Our decisions about which and how many tangible assets to invest in are often at the center of our economic lives and practice of investing. We are constantly faced with choices about when to convert some of our financial assets into tangible assets. While our homes and property are commonly considered “investments” because of their potential to gain value, this is the exception rather than the rule among tangible assets, many of which degrade in resale value quite quickly. We often choose to buy something that we know will never provide a financial payback because we believe it will enrich our lives in other ways. In addition, our possessions make apparent the impact we have on the world through our purchasing choices—all that stuff we have in our houses and garages offers the opportunity to contemplate the natural and human resources that were required to make and transport it to us.

But tangible assets also extend beyond the things within our personal grasp. The burgeoning “sharing economy” surely involves tangible assets, whether it’s owning tools collectively with others or joining a car-sharing service that provides you with a vehicle when you need it. You might choose to invest in local food security by joining a community-supported agriculture (CSA) farm.2 The parks, libraries, and other shared resources we enjoy in our communities are also part of our tangible portfolio.3 On a larger scale, you may decide to support efforts that create tangible benefits to the local or global community and the biosphere. This could include things like habitat conservation and wildlife corridor projects around the globe, efforts to keep water rights with the land rather than sold to distant cities, and investments that conserve agricultural land for future generations of farmers. Ultimately, a healthy, functioning ecosystem is our most fundamental tangible asset, one that we all hold in common.

Personal and Social Assets

Personal and social assets (which we refer to simply as personal assets) compose the row that we are least likely to think of as part of our investment choices, and for that reason we’ll invest a few more words in this section! Though it’s off our investment radar, this is humanity’s oldest asset class and is still the one in which many of us are most actively engaged. Here we take care of ourselves—mind, heart, body, and soul—as well as nurture the web of social relationships that define us: partner, family, neighborhood, school, church, community, culture, country, and even global social networks.

Personal and social assets (which we refer to simply as personal assets) compose the row that we are least likely to think of as part of our investment choices, and for that reason we’ll invest a few more words in this section! Though it’s off our investment radar, this is humanity’s oldest asset class and is still the one in which many of us are most actively engaged. Here we take care of ourselves—mind, heart, body, and soul—as well as nurture the web of social relationships that define us: partner, family, neighborhood, school, church, community, culture, country, and even global social networks.

Our social, interpersonal relationships are an essential kind of wealth that cannot be ignored; they require dedicated investment to reap the human returns that we each need in our life. We all have many examples in our personal lives of the ways that friends, family, and professional, recreational, or faith networks have carried us through our times of greatest need. In the face of the complexity and uncertainty that we are addressing throughout this book, these personal assets are likely to be the most stable and valuable form of investment that most of us hold. Best of all, they tend to reap the highest returns when times are rough.

Volunteering at a local soup kitchen, joining advocacy groups and getting active in politics, and pitching in at your kid’s school—all are ways to invest and grow your personal assets. It is widely accepted that altruistic and charitable actions not only help the intended recipient but also give the donor substantial benefits ranging from stress reduction to being held in higher esteem in the community.4

Lifestyle choices can build these assets, as well. This might be simple things like working in your garden or learning to do your own plumbing repair, activities that build your personal assets (enjoyment and skills) while adding to your tangible assets (nicer home) and conserving financial assets. How do you want to invest your leisure time? Does a little voice in your head whisper that it’s time to make a career change? One corollary of complexity is that we now have many more choices, over more aspects of life, than any generation that came before us. This means we have more decisions to make, but it also provides us with more opportunities to shape our lives in very personal ways.

The same is true for your family; giving generously of your time, money, and attention to encourage their interests and growth will have a positive impact on your life as well as theirs. Sharing music and the arts, exploring and learning about nature by hiking and camping together, supporting their education and personal development—all will show rich returns in your relationships and in the lives of your kids as they come of age. For those with the means, taking even one trip abroad to show American children what life is like for people in other countries is a powerful reality check that can foster a feeling of gratitude and appreciation for their own lives as well as a social consciousness that can guide them toward ethical choices.

And then there’s the really personal: taking care of yourself. Here are your most internal investments: diet and exercise choices that foster health, education, and lifelong learning in a range of forms as well as spiritual nourishment and growth. Sometimes taking a walk is all you need to regain some perspective; at those times that walk is the best investment you can make. Other times you might really need to buckle down and learn some new skills, or dedicate time to healing a chronic condition.

Again, these are the kinds of investment decisions we make all the time, but by being mindful of the choices we’re making we can become more aware of how they support, or do not support, the goals we’re pursuing with our other assets.

Putting energy into your community, improving your relationship skills, participating in both real-world and online networks relevant to your interests—all are ways to strengthen the personal and social elements of a resilient life. When you invest time and money in things you believe in, the intangible returns that flow back can often outshine the financial returns that are overemphasized in our society. Forming and growing these connections builds your social capital, a value term that even economists can appreciate.

Finally, many people find essential meaning by cultivating their spiritual life. One of the bounties of living in these times is our access to a wide range of wisdom traditions sourced from many cultures and eras. Organized religion falls into this realm, as do both secular and nonsecular meditative practices. Or perhaps you prefer engagement with nature as a restorative and balancing force. There are many paths, but by acknowledging and connecting to a greater whole within which one’s own life plays out, and learning to quiet the chatter of our minds, we can find ourselves gaining in both purpose and direction.

In fact, many of the authors who have been thinking about this age of complexity are strong advocates of investing time and energy into one’s spiritual life, citing returns that include cultivating a grounded sense of equanimity and calmness as well as the development of capacities for insight and integration, essential qualities that will always be there for us as we head into the unknowable future.

It is appropriate that this forms the top row of our map, as many of us tend to downplay the importance of nurturing what integral theory philosopher Ken Wilber terms our “interiors.”5 By embracing personal assets as something you actually invest in, resilient investing has embedded within itself the practice of considering these essential realms whenever we make important decisions about our future.