Digital Shift: The Cultural Logic of Punctuation (2015)

Introduction

Textual Shift and the Cultural Logic of Punctuation

The Equal Sign Takes Over Facebook

Every day in 2013, over a million Facebook users in the United States updated their profile pictures. On March 26, 2013, however, 2.7 million (120 percent) more users than usual changed them. The overwhelming majority of the new images that accounted for this spike were variations of the same basic design: a pink equal sign on a red backdrop. This trend was due to the Human Rights Campaign’s (HRC’s) newly colored logo (now red and pink rather than their previous blue-and-yellow equal sign) to support marriage equality for homosexual Americans in the context of the Supreme Court’s hearing cases that week regarding California’s Proposition 8 and the Defense of Marriage Act, legislation that denied rights to gays in the United States. This swarm of pink-and-red pictures of symbols in squares represents a distinctly digital form of media activism whose usefulness and meanings are probably less obvious and more complicated than we might think at first. Like all popular Internet phenomena, this image generated a wave of responses and variations: from a pink “greater than” sign replacing the equal sign as a queer critique of heteronormativity by the activist organization Against Equality to an image of television’s Southern cooking icon Paula Deen edited sitting atop the image, with text reading “It’s like two sticks of butter, y’all.” Nearly all popular news websites in the week following the phenomenon compiled slide shows of their favorite variations.

Texts, as humanists know, exist in contexts. What might we discern about the context of this visual text, a pink equal sign in a red square, that millions of people adopted as their online avatar? How do we understand the significance of its politics? How does it relate to the Supreme Court hearings that occurred in conjunction with it? What picture does this image of the equal sign paint of American media and society in our digital twenty-first century? In what set of conditions does it make sense as a cultural phenomenon?

While the flood of pictures generated some expected criticism of the effort for having few practical political consequences — a critique lodged in terms for phenomena to which this could be said to belong, like slacktivism or clicktivism — the unprecedented number of changes made visible the massive public support for marriage equality. It undoubtedly serves as a strong visual statement about the popularity of the cause of gay rights among mainstream sentiments. In response to the mass picture change, an article published on the blog of Visual AIDS suggests,

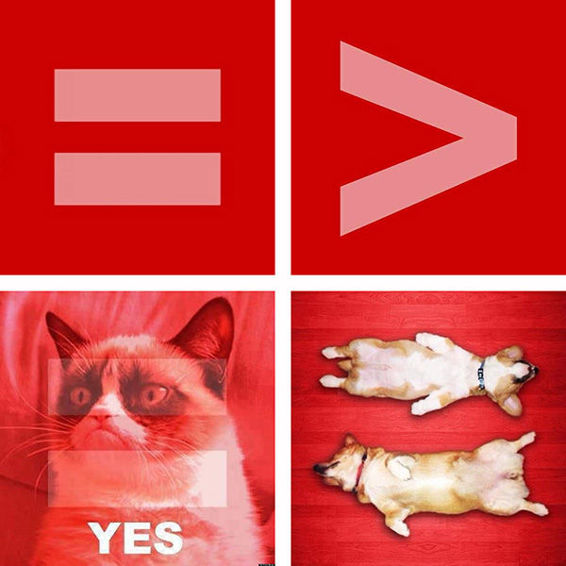

Figures 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d. HRC’s Facebook equal sign profile pictures and variations

Photoshop activism may seem like a silly thing, creating an image, being part of a picture-based conversation. But one of the numerous lessons we can gleam [sic] from ongoing AIDS activism, is that expression matters. It is not the be all and end all, but art helps interrupt a conversation, create new ways of thinking, provides a way to heal while acting up, and broadcasts dissent when words are not enough.1

The authors also quote Djuna Barnes: “An image is a stop the mind makes between uncertainties.”2

Between these and indeed probably other uncertainties, it is easy to take the contemporary phenomenon of the mass picture change for granted and as obvious, but what if we reflect on it as strange and unnatural, as if we are historians or cultural critics from the future looking back or societies of the past looking forward: How did we get here? I would like to pause, then, on something that not many observers have discussed in relation to this widely circulated and altered image: its actual content. It contains one simple typographical mark: an equal sign.

The equal sign, while not technically punctuation, is nevertheless like punctuation in that it is a single typographical mark that helps us make sense of the relationship between the two terms it comes between. It is what we might think of as loose punctuation as opposed to strict punctuation. In the digital mediascape, traditional conceptualizations of the parameters of punctuation as a category of typographic symbols no longer seem adequate to characterize the range of signification practices at play in textual exchanges. As I will argue more extensively at the end of this book in relation to the hashtag, identifying such a mark as punctuation, when it has not traditionally been used in writing as punctuation, productively alerts us to shifts in the ways language and image relate to each other via contemporary textual practices. Perhaps the most illustrative and familiar example of this is writing emoticons, where iconic compositions of punctuation integrated within textual exchanges call attention to new configurations and alliances between language and image within social practices, mirroring and standing in for a broader shift that has occurred with the emergence of digital media cultures. To understand how we have arrived here, for now we can think of loose punctuation like the equal sign and strict punctuation like the period and parenthesis together as belonging to a larger set of typographical marks that function with other typographical marks and units of language to signal a set of semantic and aesthetic relations. If not yet, hopefully by the end of this book, my readers will be comfortable with this expansive view of punctuation, convinced of this shift and how it helps us understand media, textuality, and aesthetics in the digital age.

Since its emergence in the mathematical context in which it was introduced in the sixteenth century, the equal sign is supposed to fall between two different terms, indicating that between them there is a relationship of equality, and thus of interchangeability and identicalness. But what does it mean when, here, the symbol stands by and for itself, isolated as a logo for a political media campaign? Furthermore, to what extent does its widespread circulation and reappropriation depend on the text being removed from its general contextual signifying practices and isolated?

Kant usefully implies in his Prolegomena that the equal sign is not as neutral as its users might like us to believe. He writes,

It might at first be thought that the proposition 7 + 5 = 12 is a mere analytic judgment, following from the concept of seven and five, according to the principle of contradiction. But on closer examination it appears that the concept of the sum of 7 + 5 contains merely their union in a single number, without its being at all thought what the particular number is that unites them. The concept of twelve is by no means thought by merely thinking of the combination of seven and five; and, analyze this possible sum as we may, we shall not discover twelve in the concept. We must go beyond these concepts by calling to our aid some intuition corresponding to one of them, i.e., either our five fingers or five points. . . . Hence our concept is really amplified by the proposition 7 + 5 = 12, and we add to the first concept a second one not thought in it. Arithmetical judgments are therefore synthetic, and the more plainly according as we take larger numbers; for in such cases it is clear that, however closely we analyze our concepts without calling intuition to our aid, we can never find the sum by such mere analysis.3

In other words, the equal sign does not just neutrally identify a relationship, it serves to make meaning, directing our thought to a relationship of equality between two terms that we do not a priori associate with each other — whether between the ideas of 5 + 7 and 12 or what this image wants to forge an association between, rights to heterosexual marriage and rights to homosexual marriage. To recall a more recent statement about the sign, consider, “2 + 2 = 5 (The Lukewarm),” the opening track of the band Radiohead’s 2003 Hail to the Thief album. Anticipating the album’s thematic focus on dishonesty, the song exposes the symbol’s conceit, confronting us with the equal sign’s power to signify our false hopes in fact and neutrality directly and effectively by presenting us with an incorrect equation, and hence the sign’s construction of meaning.

When the equal sign is isolated and is able to activate political signification processes, it indicates that we are in a particular textual regime, one where inscriptions that are not words are nevertheless able to be semantic, sufficient, and communicative. One specific way to understand this textual condition is in its correspondence to what Naomi Klein describes as the newly emergent role of the logo in the 1980s and companies’ “race toward weightlessness,” aiming to maximize the circulation of powerful images and minimize the creation of actual material products with its reliance on labor.4 Klein explains, “This scaling-up of the logo’s role has been so dramatic that it has become a change in substance. Over the past decade and a half, logos have grown so dominant that they have essentially transformed the clothing on which they appear into empty carriers for the brands they represent.” Referring to high-end apparel company Lacoste’s logo, she concludes, “The metaphorical alligator, in other words, has risen up and swallowed the literal shirt.” This shift resonates with Jean Baudrillard’s thoughts about postmodernity’s secessions of simulacra, where a primary, material realm is subsumed by a secondary, immaterial, image-based economy of exchange.5

To my mind, the power and spread of the Human Rights Campaign’s modified equal sign logo across the Internet is inseparable from these same issues raised by critiques of capital and discussions of postmodern semiotics, unfashionable as that periodizing category may have become at the current moment. As Ryan Conrad of Against Equality has noted, the campaign for marriage equality has been spearheaded by extremely well-funded nonprofits that are inextricable from the capitalist ideologies of neoliberalism.6 I will return to this concern with postmodernism as an ongoing inquiry in this book, as I believe that in the context of the digital, the status of postmodernity is productive to interrogate and, contrary to what we might think, it has not been exhaustively explored. To not scrutinize the power of images and their signifying practices across digital culture would be intellectually shortsighted.

In addition to “liking” and “posting,” we need to remember that there is an arsenal of strategies available for engaging with contemporary visual culture, including long traditions of aesthetic and semiotic inquiries. Indeed, when Facebook’s profile pictures transform into a sea of typographical symbols, is this not an all-too-literal manifestation of our real bodies becoming data bodies? On some level, does this sea change not ironically indicate that our selves are interchangeable with interchangeability itself? To answer in the affirmative with conviction, it is useful to imagine an alternative scenario. Would it have been possible to substitute the equal sign with an image of two members of the same sex in wedding attire, exchanging vows or kissing, which would then have been adopted by millions of users as their avatar? Or perhaps even more radically, imagine a scenario in which each individual member posts a photo of himself or herself engaged in an act of homosexual love, however he or she interprets the concept. With the equal sign, we must concede that we are algorithmic functions, machine parts of capitalism: data bodies that like, not human bodies that love.

In an age when we are increasingly constituted as data bodies, when our habits and knowledge are shaped by algorithmic functions and equations, typographical symbols to a certain degree have taken on the power to stand in for our selves. Significantly and compellingly, the equal sign could be read as an allegory of what David Golumbia has referred to as the “cultural logic of computation.” He writes, “There is little more to understanding computation than comprehending this simple principle: mathematical calculation can be made to stand for propositions that are themselves not mathematical, but must still conform to mathematical rules.”7 Golumbia contends that rather than representing an unprecedented, new historical rupture with previous philosophical traditions as so many writers about “new” media want to have it, computation in fact is an extension, culmination, and utopian realization of rationalism, a mode of thought that has been pursued for centuries. The wide circulation of the equality logo thus presents us with an allegory of our immersion in computationalism, where the desire to rid ourselves of ambiguity represented by mathematical calculation seamlessly extends to the logics of visual culture.

The Cultural Logic of Punctuation

Where Golumbia writes of computation’s “cultural logic,” in this book, I write about punctuation’s “cultural logic,” a phrase popularized in critical theory by Fredric Jameson’s study of postmodernism, terms that he himself could have used an equal sign in front of when suggesting the substitutability of the terms “postmodernism” and “the cultural logic of late capitalism” in the title of his landmark “Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” As Jameson writes there, “I have felt . . . that it was only in the light of some conception of a dominant cultural logic or hegemonic norm that genuine difference could be measured or assessed.”8 Following Jameson’s reliance on the phrase’s assistance in the identification of difference (a pursuit that critics of Jameson tend to forget is his ultimate interest), I also find cultural logic a useful phrase for thinking about how dynamic, structuring, and shared ways of thinking — both obvious and not obvious — are inscribed in and interact in a single site. My use of the term, however, departs from, if still hopefully resonates with, the more directly Marxist connotations it carries in Jameson’s work. I use it more specifically in relation to “punctuation” — and unlike Jameson’s “late capitalism” and Golumbia’s “computation,” punctuation as a concept has been around as a seemingly stable category for hundreds of years. Working through punctuation’s cultural logic, we will be able to identify how these typographical marks correspond to particular styles of thinking, and how, in the context of the emergence of digital media, the roles of textuality in media culture have undergone a series of shifts. I am not arguing that there have been erosions or eruptions, but I am claiming there have been what one could envision as shifts in balance, in distributions of conceptual weight, in values and valences, in storytelling and communication habits, and in aesthetic and social relationships that changes in the cultural logic of punctuation help us measure. While I am very sympathetic to the resistance of Golumbia (and indeed, so many critics, such as Lisa Gitelman and Wendy Chun, to name primary examples) to the rhetoric of digital media’s “newness,” it is nevertheless equally as easy and problematic to discredit the significance of the profound changes that have accompanied the emergence of the digital. For a variety of reasons, punctuation and nonalphanumeric symbols, as marks that have existed (and changed) for centuries of writing, anchor opportunities to weigh these continuities, shifts, and expansions that can be sensed as occurring with the ongoing popularity of networked computing. By drawing attention to the concept of textual shift, I aim to both map out some significantly distinct textual dynamics of the digital era and to be wary of overstating divides and differences.

The example of the equality sign certainly does not tell the full story of this shift, but it offers a snapshot that sets the stage. Its aesthetics and politics, and its cascading contradictions, put us on a path for thinking more seriously in our contemporary postmillennial context about what Marshall McLuhan sought to explore fifty years ago as “typographic man,” a phrase that presciently forecasts the weight of electronic media’s textual shifts upon our consciousness and suggests that they have been tangibly perceptible and in the works for decades.9 With various textualities proliferating across our media landscape, zeroing in on specific punctuation marks sets in motion an intermedial series of questions about reading protocol and the social-affective dimensions of textual systems. Before we fully pursue this line of thought, a working definition of punctuation, along with a common understanding of its functions, is in order.

While we might be inclined to view punctuation marks as textual units predating language, out there in the world for us to pluck from the air (or more literally from the surfaces of our keyboards and typing pads) as we wish to write, they are not natural. Punctuation marks are invented inscriptions that arose in particular historical contexts, and their meanings have cyclically congealed and fluctuated in a variety of subsequent historical and linguistic contexts. As social inscriptions, they therefore carry with them ideological underpinnings. As stylistic markers, their usages reflect epistemological and aesthetic conditions. This is what Theodor Adorno provocatively observed in his terrific and somewhat uncharacteristic short essay on punctuation: “History has left its residue in punctuation marks, and it is history, far more than meaning or grammatical function, that looks out at us, rigified and trembling slightly, from every mark of punctuation.”10

M. B. Parkes’s Pause and Effect: An Introduction to the History of Punctuation in the West provides, as the book’s subtitle suggests, a more comprehensive overview of the evolving histories of punctuation marks, at least in the context of European languages and with the development of the printing press, which significantly stabilized punctuation and largely made it necessary. As Bruno Latour puts it, the printing press brought into circulation “immutable mobiles,” standardizing the form of inscriptions yet also enabling them to travel.11 Parkes explains, “Punctuation became an essential component of written language. Its primary function is to resolve structural uncertainties in a text, and to signal nuances of semantic significance which might otherwise not be conveyed at all, or would at best be much more difficult for a reader to figure out.”12

It is important to understand, then, that punctuation’s history coincides closely with the history of the mechanical reproduction of written language. In antiquity, language was viewed as an oral medium; texts were conveyed by the voice, to the mind. Through the Middle Ages, reading and writing continued to be seen as activities for an elite, educated few, and texts would often be studied and prepared carefully. Readers would practice proper readings, learning when to articulate appropriate breaks. Textual marks were experimented with to indicate such cues, but no standards were in place. With the invention of the printing press, as so many historians have documented, the book became a popular medium. This had two important consequences for the history of punctuation — one technological, the other social. First, now that it had to be set into movable type, punctuation became much more standardized than it ever had been. Second, with the subsequent rise in accessibility of the printed medium, written texts were no longer exclusively for an educated upper class that took time to practice reading aloud, but books were now read alone and by a mass audience. It became important for reading to be made economical and accessible, and for books to contain as little paratextual ambiguity as possible to facilitate reading practices. Punctuation served these purposes.

Punctuation marks are cues that writers leave for readers. They are meant to guide us and suggest how to move through the words that they fall between, giving us pause at appropriate moments to maximize our comprehension. As Parkes puts it, they “resolve uncertainties.” Punctuation marks in this sense are reading tools, aids that help convey meaning. They help us hear how text might sound if it were to be spoken. In this sense punctuation marks are sometimes perceived to have musical qualities. Adorno writes, for example, “There is no element in which language resembles music more than in the punctuation marks. The comma and the period correspond to the half-cadence and the authentic cadence. Exclamation points are like silent cymbal clashes, question marks like musical upbeats, colons dominant seventh chords; and only a person who can perceive the different weights of strong and weak phrasings in musical form can really feel the distinction between the comma and the semicolon.”13 Punctuation as Adorno sees it lends the written word a range of sonic qualities. By extension, one might consider the ways in which it adds a contrapuntal dimension to the text in which it occurs, in its relations with the words it punctuates, and in the ways in which punctuation registers expressivity and affects of a different sort than is possible with alphabetic language. Punctuation marks, in other words, represent a coded system composed of a range of symbols that work with and alongside the alphabet, a distinct but related coded system.

Punctuation’s affinities with music offer a suggestive hermeneutic framework too for thinking about punctuation’s especially frequent references in indie rock of the 2000s — from Sigur Ros’s album simply titled ( ) and the band Parenthetical Girls to the band !!! and Vampire Weekend’s single “Oxford Comma,” to name just a few examples where the use of marks signifies a countercultural aesthetic departing from the mainstream. In the case of !!! or Sigur Ros’s album, for example, how is one even supposed to pronounce the band’s name or the album’s title? Audiences must be in the know to know that the most common way to pronounce !!! is “Chk Chk Chk.” By being stand-alone punctuation marks, both !!! and ( ) resist the primary function of punctuation — making the transition from reading to pronunciation easier — and instead render locution more difficult. The third chapter’s discussion of parentheses further contextualizes this aesthetic, as these marks in particular channel an alternative spirit and raise provocative questions about sound.

Textual Shift

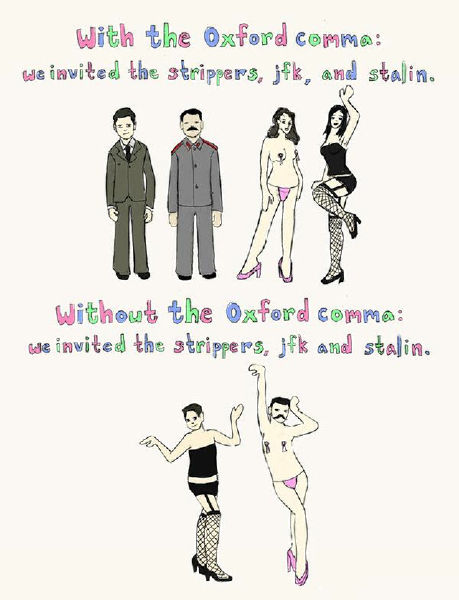

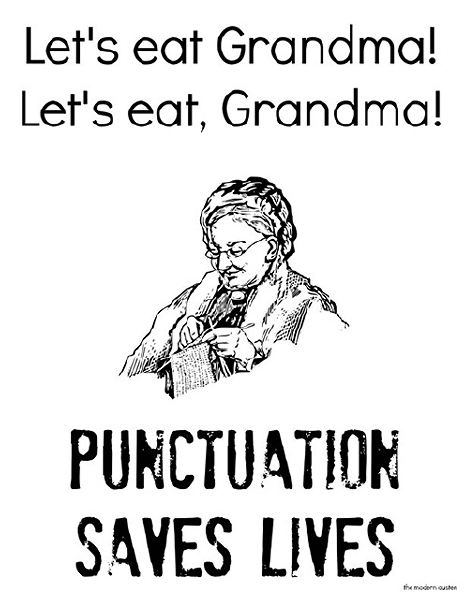

At the same time that punctuation might seem to be seeping into our earphones and onto the screens of our handheld devices, I write this book surrounded by a nagging anxiety that the days of the book — and closely connected with this, the idea of what it means to care about punctuation — might be numbered. This sentiment is echoed for example in a wide range of humorous image macros that have circulated online, which illustrate the drastic semantic differences slightly varied uses of punctuation can make — from the widely circulated JFK-Stalin-stripper Oxford comma pun to the “Let’s eat, Grandma” meme. Lurking behind these humorous images, one senses, is a more paranoid critique that we no longer know how to use language correctly, or care to.

Figure 2. Punctuation image macros. “With the Oxford comma: we invited the strippers, JFK, and Stalin. Without the Oxford comma: we invited the strippers, JFK and Stalin.”

Figure 3. Punctuation image macros. “Let’s eat Grandma! Let’s eat, Grandma! Punctuation saves lives.”

Long-form reading is on the decline and many scholars and authors surely wonder who will read the books they devote years of thought and labor to write. Do contemporary academic books speak to only a handful of specialized scholars, or worse yet to the last generation of people who might actually read a monograph with a theoretical orientation? Writing about punctuation and visual culture has in this sense necessarily been accompanied by a certain degree of self-reflexivity, allowing me to think about and speak to broader anxieties about language, and more specifically the changes in textual practices that have coincided with the emergence of digital media. These are among the textual changes I have in mind throughout this book when I refer to the idea of shift. Though much of this book comes from a self-reflexive space, the reader will find I have largely left myself out of it — other than in its idiosyncratic writing style and series of curiosities — for the sake of focusing on cultural analysis and putting forward ideas that will hopefully circulate and resonate beyond their own immediate moment of articulation.

This book has two overarching purposes, which at times work on separate but parallel tracks, at other times push up against each other to reveal their limits, and in their most provocative moments work on multiple levels to create a textured inquiry, as if in a performative dance. First, this book aims to simply describe a condition of contemporary culture in a comparative way that draws on a range of objects, texts, and media histories. The condition described is one in which textuality’s role has, in the context of the emergence of digital media, undergone profound changes. Most radically, this shift can be understood as one where our commonsense, established understanding of meaning has effectively been disconnected from textual inscriptions. On this level the book builds on and synthesizes many familiar arguments from critical theories about postmodern culture, whose reach has not been fully thought through and mapped out in relation to digital media and culture. I choose to map this shift, for reasons suggested above and elaborated further below, via punctuation marks and related typographical characters. This goal of the book might be understood as being more expository and observational, a mode that seems to me necessary but not alone sufficient for the critical apprehension of any contemporary or historical cultural logic.

The second aim of this book is less expository and more hermeneutical and imaginative. Broadly, I hope to suggest that the scales and scopes of humanistic inquiry need to be rethought and creatively imagined beyond the confines to which the questions we pose and the objects we examine are often limited. Beginning with single punctuation marks as units for thinking across media forms, I aim to discover unexpected connections and insights that fall outside the parameters of the book’s argument and first aim. What opportunities does beginning with a punctuation mark — nearly as microscopic a unit of textuality as one can cognitively process, aside from perhaps a drop of ink or a pixel — open up for a critic essaying to describe a text or for an everyday web user aiming to understand the visual culture of the Internet?

Here, like Walter Benjamin’s famous description of the Angel of History, the book moves forward while looking backward, arguing for the continued usefulness of semiotic inquiry in and for the digital age. Now as much as ever, we must attend to questions of the meanings of textual procedures. Just because texts spread so fast, across multiple formats, just because they are here today and gone tomorrow, seeming impossible to apprehend, are not satisfactory excuses to refrain from singling out moments within the visual culture of textuality and analyzing what we see when we engage in such critical isolations. As Jodi Dean writes, “A problem specific to critical media theory is the turbulence of networked communications: that is, the rapidity of information, adoption, adaptation, and obsolescence.”14 Think back to the example of the equal sign phenomenon with which this chapter opened. Facebook — a corporate platform that translates identities into data and then sells it to marketers, particularly via the popular habit of “liking”—encourages an ephemeral engagement with images and the ideas they generate, but in effect its “newsfeed” design emphasizes the nowness and newness of the present and actively discourages sustained, critical engagement. The very appearance of the equality sign image across Facebook therefore poses a paradox in terms of how to confront its effects, which would seem momentarily vast rather than longitudinally significant. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun would view its paradoxical effects as being part of digital media’s temporality that she refers to as the “enduring ephemeral,” never quite there but never quite gone, always there for us to access as a moment in history but almost immediately lost and forgotten in a digital archive.15

In focusing on punctuation’s relationship to visual culture and critical theory, it is instructive to recall one of critical theory’s most influential concepts, Roland Barthes’s punctum, which Michael Fried notes parenthetically in an essay “has proven almost as popular as Benjamin’s aura.”16 (Key observations in and about theory are often inconspicuously tucked away inside parentheses, as the third chapter will claim.) Barthes introduces the idea in his book on photography, Camera Lucida. He expresses dissatisfaction as a critic with language’s ability to describe the photographic experience, ontologically based as it is not in verbal language but in the image. He explains that in wanting to write about photography, he became aware of a “discomfort” he “had always suffered from: the uneasiness of being a subject torn between two languages, one expressive, the other critical. . . . For each time, having resorted to any such language to whatever degree, each time I felt it hardening and thereby tending to reduction and reprimand, I would gently leave it and seek elsewhere.”17 He introduces two concepts — the studium and the punctum — to both address and move beyond this critical impasse. For Barthes, the studium characterizes a sort of general interest, a standard reading based in an educated, shared perspective, but as he says, “without special acuity.”18 By way of contrast to this, he develops a discussion of the punctum, his introduction of which, even if familiar, is worth quoting fully:

The second element will break (or punctuate) the studium. This time it is not I who seek it out (as I invest the field of the studium with my sovereign consciousness), it is this element which rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me. A Latin word exists to designate this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument: the word suits me all the better in that it also refers to the notion of punctuation, and because the photographs I am speaking of are in effect punctuated, sometimes even speckled with these sensitive points; precisely, these marks, these wounds are so many points. This second element which will disturb the studium I shall therefore call punctum; for punctum is also: sting, speck, cut, little hold — and also a cast of the dice. A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).19

The idea of the punctum allows Barthes to conceptualize a personal encounter with a work of art, to identify a particular detail in a photograph that speaks to him as a spectator. It is not something intended by the artist; rather it represents a unique experience on the part of the observer that idiosyncratically elevates his aesthetic investment in a piece beyond the more ordinary level of the studium. Fried explains its central import succinctly: “The punctum,we might say, is seen by Barthes, but not because it has been shown to him by the photographer, for whom it does not exist.”20

As Fried observes, Barthes’s punctum is one of the most frequently referenced concepts in theoretical discussions of photography and related arts. Rather than rehearsing these theoretical appropriations and debates about photography here, I would prefer to briefly linger on the term’s actual etymology. What is interesting is precisely that the punctum is such an influential, resonant concept in tandem with the fact that it, as Barthes writes, “refers to the notion of punctuation.” Indeed, for all the term’s critical circulation, relatively little has been written about the concept’s relation to punctuation, which is to say nothing of Barthes’s own elegant and precise punctuation. Barthes turns to the concept because the punctum breaks, interrupts, “pricks,” “wounds,” “rises from the scene, shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces” him. The punctum as he frames it can both refer to literal “marks” in an image (“sometimes,” he writes, photographs are “even speckled with these sensitive points”) and more metaphorical marks, which are “in effect” punctuated, “rising from the scene.”

It is fascinating, if somewhat unintuitive, that Barthes attributes such punctuations of the image to elements that the artist did not intend to be there, to characteristics that in his encounter with the photograph he discovers unexpectedly; to what has been seen, not shown, to recall Fried’s summarization. It is worth considering what this implies about how Barthes conceptualizes punctuation. Recall that a punctuation mark’s purpose in writing is to aid the reader. It is, one could say, a quite intentional mark left in the text for the reader, a figure whom we could analogize to Barthes’s photographic viewer. This likeness by Barthes’s logic takes us only so far, then, as punctuation marks — unlike the punctum — are generally deliberately, even artfully, inscribed by writers. Combined with this move punctuation forges from the writer to the reader, punctuation for Barthes nonetheless seem to be as close as one can get to an appropriate metaphor for parts of a work that are easily overlooked and neglected, not noticed by everyone. In fact, reading the punctum more directly in the context of punctuation could serve to revise the concept’s tight connection to that which is not artistically intended, to instead associate it with that which is not noticed by most viewers, refined as their observational skills might be.

To align the inquiry to the present questions at hand, I wish to emphasize that a punctuational concept serves as Barthes’s answer for moving beyond the impasse or incompatibility between image and language, or what he refers to as the “reduction and reprimand” that take place when “critical” language encounters “expressive” language.21 It enhances our attention to the production of visual critique to remember that the punctum is so intimately tied to punctuation. Punctuation marks hover between and beyond language and image — almost, one could say, both and neither at the same time. Thus it makes sense that they are closely related to Barthes’s identification of a way to mediate the impasse between the photograph and the critical text. Focusing on punctuation enables one to move between visual culture and critical theory in a comparative manner, to think through the dimensions of text’s visibility in and structuring of both language-based criticism and image-based media.

An additional layer of resonance to punctuation’s place in mediating between medium and thought emerges when comparing the aesthetic value Barthes attributes to the punctum with Vilém Flusser’s claims about medium differentiality and writing in his 1987 book, Does Writing Have a Future? Flusser writes that an “inner dialectic of writing and its associated consciousness, this thinking that is driven by a pressing impulse, on one hand, and forced into contemplative pauses, on the other, is what we call ‘critical thinking.’ We are repeatedly forced to come up from the flow of notation to get a critical overview. Notation is a critical gesture, leading to constant interruptions. Such crises demand criteria. What is true of notation is true of all history.”22 If for Barthes the dialectic in question is that of image and language and in the space of the synthesis we find critical work, then Flusser offers a similarly dialectical view of criticism, emerging out of opposing processes of “pressing impulses” and “contemplative pauses.”

Recall that the title of Parkes’s book on punctuation is Pause and Effect, where pause is the effect in writing that punctuation historically instantiates. The earliest marks, such as empty single spaces, periods, and commas, aid readers because they indicate where to pause, reducing ambiguity and heightening clarity. On a sentence-level scale, then, following Flusser, one could view punctuation as the inscriptions of such moments of contemplation, pauses allowing readers to stop and think, however momentarily. This book wagers that punctuation across media forms and contexts provides brief moments for thought, collected in the following pages of reflections.

The affinities tying Flusser to Barthes and to punctuation are stronger still. Consider Flusser’s following observation, just a few pages after the one cited earlier.

A scientific text differs from a Bach fugue and a Mondrian image primarily in that it raises the expectation of meaning something “out there,” for example, atomic particles. It seeks to be “true,” adequate to what is out there. And here aesthetic perception is faced with a potentially perplexing question: what in the text is actually adequate to what is out there? Letters or numbers? The auditory or the visual? Is it the literal thinking that describes things or the pictorial that counts things? Are there things that want to be described and others that want to be counted? And are there things that can be neither described or counted — and for which science is therefore inadequate? Or are letters and numbers something like nets that we throw out to fish for things, leaving all indescribable and uncountable things to disappear? Or ever, do the letter and number nets themselves actually form describable and countable things out of a formless mass? This last question suggests that science is not fundamentally so different from art. Letters and numbers function as chisels do in sculpture, and external reality is like the block of marble from which science carves an image of the world.23

Letters and numbers, in the broader view Flusser lays out, correspond with distinct ways of thinking — auditory and visual, respectively — a perspective one finds implied here. In the increasingly digital age of the computer, the visual, numbered mode, Flusser claims, takes center stage over the auditory, lettered mode that previously prevailed. This formulation coincides with this book’s own broader view of the notion of shift. But for the moment note that, drawing on richly evocative maritime and sculptural metaphors, Flusser is trying to understand how categories (letters and numbers) for phenomena might limit our abilities to grasp the full spectrum of experience, not unlike Barthes’s unsatisfactory encounter with the studium. (We are also not conceptually far removed from Wittgensteinian philosophies of language.) Before this passage, he writes, “The alphanumeric code we have adopted for linear notation over the centuries is a mixture of various kinds of signs: letters (signs for sounds), numbers (signs for quantities), and an inexact number of signs for rules of the writing game (e.g., stops, brackets, and quotation marks). Each of these types of signs demands that the writer think in the way that uniquely corresponds to it.”24

While Flusser here makes a passing reference to punctuation alongside letters and numbers as a distinct set of signs corresponding to a distinct type of thought, it is curious that in his discussion just a couple pages later, this “inexact” third character set is abandoned. If as Flusser writes in these pages, letters describe and numbers count, and if he suggests that procedures of description and counting might exclude alternative epistemological and phenomenological dimensions, an example of such a dimension would, one might strongly suspect, be found in punctuation.

For Flusser and Barthes alike, then, punctuation engenders a needed but insufficiently pursued frame within which to stage the critical encounter with media: For Barthes, it offers a passing but structuring metaphor for a critic’s ability to perceive the unintentional mark in the text that makes the work of art exciting and validates criticism. For Flusser, punctuation is a more literal type of textuality that corresponds to a logic that is neither for description nor for counting, neither visual nor auditory. Indeed, what “unique” ways of thinking could we say punctuation corresponds to? If we configure punctuation as Flusser’s fishing net, what undescribable and uncountable things will emerge from the ocean?

Importantly, both Barthes and Flusser point to punctuation as a neglected dimension, if differently. For Barthes punctuation stands in for the neglected, while for Flusser punctuation is, given his extensive focus on writing’s symbols, more symptomatically neglected. Punctuation marks as reading lenses for thought raise interesting questions about what we take for granted. They are tiny bits of textuality that are smaller units than words — and only the most sensitive of writers pay careful attention to word choice, which is to say nothing of punctuation. The speediness with which we are able to communicate with one another today via the keyboards of interconnected computers and mobile devices would seem to trump a certain care for language ensured or taken for granted by the rhythms and practices associated with slower, predigital methods of writing. Indeed, a cursory glance at communication online and in SMS text messaging might even suggest we tend to forget punctuation altogether — dropping periods and question marks from the ends of sentences, not bothering to include commas where they once would have been needed.

On the other hand, paradoxically, it might seem that punctuation is everywhere. In graphic design, in the emoticons we text to one another, in computer code, in the proliferating textualities we see on screens in the street and on screens at home. As Johanna Drucker notes of our “postalphabetic” era, “Contemporary life is more saturated with signs, letters, language in visual form than that of any other epoch — T-shirts, billboards, electronic marquees, neon signs, mass-produced print media — all are part of the visible landscape of daily life, especially in urban Western culture.”25 In this context, one might think of endless examples of punctuation’s visibility.

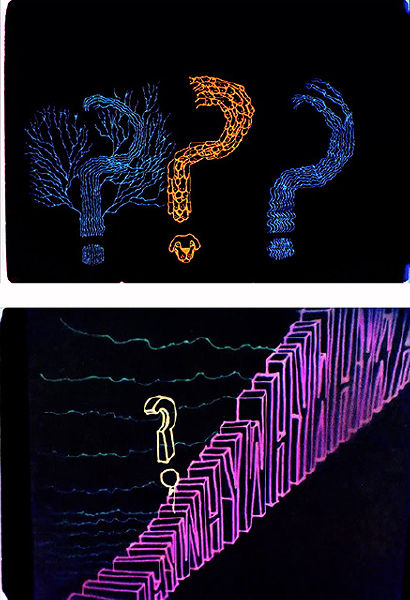

Figure 4. Question mark as vanishing point: information booth outside the Mont-Royal subway station in Montreal. Photo by author, 2013

Both lines of thought — that punctuation is nowhere and that it is everywhere — could, it would seem, be argued persuasively. But discerning a distinction helps make this paradox less paradoxical: the first scenario (punctuation is nowhere) relies on a predominantly linguistic conceptualization of punctuation, while the second (punctuation is everywhere) relies on a predominantly visual one, which W. J. T. Mitchell would associate with the “pictorial turn.”26 I therefore take this paradox as a starting point from which to launch the following argument: Language and image, two signifying spheres that we traditionally conceptualize as discrete, today increasingly overlap and change functions as screen technologies proliferate and form the interfaces of everyday life. Punctuation marks, symbols that hover between and beyond image and language, provide a unique opportunity to harness these shifts in language-image relations.

Thinking Punctuationally: Comma Boat

While this book relies on the distinction between language and image as being key to making sense of a textual shift that has coincided with the emergence of digital media, I also complicate it. Beyond the provocative ways in which punctuation indexes such a textual shift, I also want to invite my readers to think about the wide range of ways in which we (can) think punctuationally. Here, the following chapters share a significant amount in common with two other book-length works of cultural studies on punctuation. Marjorie Garber’s 2000 book of cultural criticism, Quotation Marks, brilliantly mobilizes these titular punctuation marks and thinks across literature, media, history, politics, the law, and affect, interrogating how, ultimately, quotation marks paradoxically but necessarily render and take away credibility. As such, Garber demonstrates how punctuation gives rise to ideas and intervenes in broader considerations of cultural discourse. This is a key previous study, and indeed might be the first to demonstrate just how pervasive and generative thinking punctuationally can be. Jennifer Devere-Brody, in her 2008 work Punctuation: Art, Politics, and Play, presents a second book to explore such associations, analyzing a wide range of performances and cultural texts not only where we find explicit uses of punctuation but also where we find visual patterns, ideas, or political discourses that recall punctuation marks, from Yayoi Kasuma’s politically charged use of polka dots on bodies in her 1960s “naked demonstrations” to driving at night and seeing “bright white lights speeding toward us along an otherwise pitch-black freeway.”27 Following Garber and Devere-Brody, I am compelled to open up any narrow conceptualizations we might have of where we find punctuation. Making this move involves understanding that marks are fundamentally structures of relation, showing us how to bring two different units (usually clauses of language but also image and thought) together. In turn, marks can be — and indeed often already are — mobilized as reading lenses through which to pose questions about how, among various cultural configurations, certain structures and sets of relations might be viewed as behaving punctuationally (such as, very generally, Barthes’s punctum), which can in turn lead us to discover patterns in political and aesthetic practices. In short, punctuation can help us theorize.

The present book’s investment in media theory, however, leads it to depart on a trajectory that sets it on a path largely different from Garber’s and Devere-Brody’s, insofar as it more centrally posits an argument that punctuation’s relationships to digital media allow us to index a large textual shift that has been occurring over the course of the past few decades, a claim that has not been pursued by either Garber or Devere-Brody. This specifically digital shift occurs in a time propelled by technological speed, the global information economy, smart phones, social networking, and corresponding reconfigurations of labor, leisure, and love. Within these new circulations, textuality — letters, numbers, punctuation marks, words, slogans, messages, user manuals, contracts, information, stories, billboards, web pages, and the visual and/or sonic inscriptions of these things — has spread far beyond the books to which it was generally more neatly confined and in relation to which it has tended to be conceptualized. In the process, textual inscriptions themselves have come to take on a greater number of functions used to enable and ensure the efficiency of communication, opening up a whole parallel set of effects, much like the secondary set of inscriptions that shift keys on our computers make possible. In this same cultural condition, everyday language practices carried over from predigital times are also undergoing notable transitions. Content of individual statements becomes briefer, requiring busy, always-connected subjects to surrender less precious time from the seemingly incessant demands of daily life and what Jonathan Crary calls the “unrelenting rhythm of technological consumption” that keeps us awake more hours and controlled by the apparatuses of 24/7 capitalism.28 Textual shorthand —ubiquitous acronyms like LOL and OMG, combined with the stylishness of leaving vowels out of words — is, meanwhile, increasingly familiar and acceptable in a variety of discursive habitats. While such changes are met with nervous critiques that echo concerns about postmodernity’s depthlessness, they are also accompanied by other important features, from an affinity with play to collaborative writing with artificial intelligence that draws on autocorrecting tools built into text-based applications for fixing typos in the final versions of files and messages we send or submit. Such habits of assistance of course might also be viewed with ironic distance, given all the “fails” such “corrects” generate — something humorous popular blogs and websites like Damn You Autocorrect capitalize upon for comedy.

These everyday changes often seem most effectively registered when removed from mundane, habitual contexts and channeled through artistic work, forcing us to encounter their experiential textures and structures of feeling through distanced creative or hermeneutic reflection. This is the effect spectators experience for example with work by contemporary video artist Ryan Trecartin, often hailed as one of the most original and important contemporary video artists working today. His videos rely on scripts with a prosody that uncannily channels the rhythm and flow of the digital-native generation’s communication practices. Made in the middle of night, they almost seem to channel the sleeplessness that Crary observes structuring global, digital exchange. The artist explains, “There’s no light coming in the windows at night, and people have fewer distractions — they’re not checking their cell phones, and their associations are weirder at night.”29 Probably the most important component of Trecartin’s videos are his scripts, which produce uncanny effects through their language’s surreal relation to sense; a spectator would have a difficult time following the exact meanings of what the characters in his videos are actually referencing. As Bryan Droitcour notes, “the forms of all the aspects of Trecartin’s work — the camerawork, the editing, the music, the makeup, and the costumes . . . — are prefigured in the way he works with words.”30 Trecartin constructs one-of-a-kind, language-laden environments in which frenetic, irreverent characters are simultaneously of our world and not, removed and present, seeming to channel an unconscious logic that is neither and both digital and human. The experience of submitting oneself to them spectatorially is likened by Allegra Krasznekewicz to “riding a roller coaster into the vertiginous depths of the Web or looking through a kaleidoscope on acid.”31 In Comma Boat (2013), a movie whose title foregrounds punctuation, the characters’ language resembles the claustrophobically narcissistic oversharing of the validation-seeking self constructed by social media platforms crossed with theatricized, bot-generated qualities of familiar spam e-mails more than it does literary conversation or performative computer code.

Figure 5. Still from Comma Boat (directed by Ryan Trecartin, 2013)

Consider the following dialogue from an early scene in Comma Boat, which has four participants, whom in the absence of names I identify with numbers, representing their on-screen positions from left (1) to right (4):

1: And she’s not talking about sex or making families that matter. Because she’s talking about um particles. Basically. I love particles. What the whore and balls . . . What the whore and balls is she saying? Yes. I love a good comma. That is the name of my cat. Comma.

3: Like survival . . .

1: comma

(4 gestures comma with hand)

3: Like survival

1: Comma. Meow

3: Before gear

1: Meow. Comma

(4 gestures comma)

3: Of the present

1: Comma

3: Type. Mega foundational shiftsssss

1: Shit

3: Shift

X (unknown, offscreen voice): comma.

1: You think you’re so smart, you can’t say the word shit. You have to say shift. Knots. Try to untie that one. Try to fucking untie that one. Right?

(4 claps)

3: She thinks she can act with her face.

4: Off. Off.

2: Veronica Mars, you’re off.

3: Esoteric.

2: Comma.

The third character seems to be more of an official, academic reporter from the media, wearing a suit and holding a handheld camera, in a mise en scène that evokes an interview. Like the rest of the entire thirty-three-minute video, originally displayed on three screens, in its single-screen version the scene is not only sonically but visually disorienting, framed by a rectangular frame on the edges that is split in half and features two other camera angles recording the same scene. This is clearly not exactly an interview, because the question/answer format that normally structures an interview is not present. Rather, the characters, especially the first and third, are talking over each other (thus becoming more of a critique of the very genre of the interview), with the first androgynous character, played by Trecartin in a black wig and with his face painted with a purple beard, seeming to negatively react to his or her distaste of the third character’s pretentious, academic language (“What the whore and balls is she saying?” “Try to untie that one.”).

The best way to read this scene is perhaps as a battle staged between an artist who resists interpretation and a critic who attempts to generate vocabulary to analyze the artist, character 3 versus character 1, high versus low culture, “shift” versus “shit.” (It is not lost on me that this dialogue makes the present book’s title and critical position vulnerable to the same pun and critique.) In fact, this scene might even be read as a playfully veiled response to Droitcour’s Rhizome essay about Trecartin, specifically his discussion of the artist’s K-CoreaINC.K (section a) (2009) — where characters, all named different national “Koreas” (Mexico Korea, Canada Korea, Hungary Korea) and presided over by Global Korea, a CEO, attempt to meet. Upon reading the video’s script, Droitcour notes,

Punctuation was invented to represent the pauses and pitches of speech; long after it moved beyond this purpose to become a set of standards for clarifying the meaning of written language, punctuation marks were remixed as emoticons when writing began to take on the phatic functions of speech. Trecartin’s unruly use of punctuation draws on all stages of its history. When, in the script’s first lines, Mexico Korea says “Yaw,,,,,,”, the comma does more than make a pause. It’s a winking eye torn from a smiling face, repeated until it’s a nervous tic. Colons join, parentheses cut, and in the designation of Global Korea’s role — before the dialogue even starts — those marks are staggered to herald K-CoreaINC.K (Section A) as a drama of belonging and difference, of where the self stands with regards to others.32

The eponymous conversation about commas in Trecartin’s video made two years after Droitcour’s article was published, whether intended so or not, could be productively viewed as a tongue-in-cheek, or even dismissive, response to Droitcour’s scholarly analysis of the artist’s earlier use of commas. Trecartin, who distances himself from associating with overly intellectual rhetoric and shamelessly admits to preferring MTV over literature, in effect reclaims the comma from critical language and brings it back into his art. He makes “comma” the name of the cat of the resistant character played by himself, reminiscent of that most banal but pervasive culture of Internet comedy: the endless hours of cat videos archived on YouTube.

The comma, the punctuation mark we use to create lists, to elongate sentences, in the dialogue of the scene adds to Trecartin’s sonic cacophony, becoming a way to articulate and tie together an aggregation of language as it traditionally does in written language. But the comma, here interjected into another speaker’s words, also cuts the critic off, as if to expose her discourse as nonsense. In pronouncing the punctuation mark out loud, the dialogue might also remind us of the act of machinic transcription specific to digital contexts: as though the characters are dictating lines to be transcribed by an artificially intelligent system, recorded for posterity’s sake. Probably even more than that, saying the name of the mark out loud after single words recalls the fashion of speech whereby people repeatedly pronounce the word hashtag in conversations — a phenomenon explored further in this book’s final chapter. Comma Boat’s dialogue in a sense has an air of the narcissistic affect Piper Marshall has written about in relation to the widespread use of the hashtag, where “our current climate is dominated by pithy punch lines that summarize the solipsist’s always already uploaded narrative.”33 Trecartin’s repeated comma effectively becomes the very mark of the ability to be redefined and recontextualized, to turn against language. Whether it is a “winking eye torn from a smiling face,” a command against interpretation, or Trecartin’s misshapen hashmark, the comma represents a structuring logic of popular culture in Trecartin’s poetic video art.

Notes on the Book’s Organization

In each of this book’s primary chapters, I aim not only to narrate comparative media histories of a distinct punctuation mark — the period, the parenthesis, and the hashmark — but also to develop discussions and launch rethinkings of theoretical concepts to which the typographical marks in question give rise. I mobilize these concepts to stage nested readings in which the ideas they generate shed light on specific texts and cultural practices and at the same time cross-pollinate one another. I aim to explain how various marks reanimate nexuses of conversations in critical theory to in fact offer fresh perspectives on the cultural histories and aesthetic practices associated with “new media” and the “digital,” and especially how they also offer us ways to problematize these categories.

I am therefore not only suggesting that punctuation marks will help anchor an understanding of cultural aesthetics and our specific textual condition, but in effect also allowing punctuation marks to carve out space in which we can reflect on how we write (and do not write) about and across media. In this sense, I build on Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann’s notion of “deformative criticism” as a mode of “engaging imaginative work.” They write that this “alternative moves to break beyond conceptual analysis into the kinds of knowledge involved in performative operation[s].”34 All acts of interpretation necessarily change a work and “dig ‘behind’ the text,” as Susan Sontag famously declared in “Against Interpretation,” and as Trecartin works through in a more roundabout way in Comma Boat.35 Samuels and McGann foreground this very inevitability of critical work, suggesting we apply strategies of literally rewriting and taking apart a text’s composition, or isolating parts of it so as to forge connections and discover what new forms of knowledge such procedures might create.

Punctuation as a topic of study in particular seems to invite us to engage in critical play: what if we switch a period with a colon, replace a pair of parentheses with a pair of dashes, or, as the JFK-Stalin-stripper meme pictured earlier suggests, leave out an Oxford comma? Indeed, to understand how punctuation matters, consider doing without it. What if we remove it from text altogether? How would such a move alter meaning? A glance in nearly any book or guide about punctuation will almost certainly include a rhetorical demonstration that juxtaposes two pieces of text containing the same words but punctuated differently so as to demonstrate the significant (and often humorous) semantic differences punctuation registers when used differently.

Parkes offers the following on the first page of his history of punctuation, for example, explaining that punctuation’s “primary function is to resolve structural uncertainties in a text.” To illustrate this point, he removes punctuation from a brief passage in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House:

out of the question says the coroner you have heard the boy cant exactly say wont do you know we cant take that in a court of justice gentlemen its terrible depravity put the boy aside.

Parkes then suggests, “When punctuation is restored ambiguities are resolved:

‘Out of the question,’ says the Coroner. ‘You have heard the boy. “Can’t exactly say” won’t do, you know. We can’t take that in a Court of Justice, gentlemen. It’s terrible depravity. Put the boy aside.’ ”36

Another common example that illustrates the strong semantic effect punctuation has and the dangerous consequences of misusing it is in the juxtaposition of two differently punctuated sentences:

A woman, without her man, is nothing.

A woman: without her, man is nothing.

The title of Lynne Truss’s Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation also refers to one of these instructional devices, a bad joke about a panda that walks into a café and shoots a gun because of a wildlife manual’s badly punctuated description of his behavior that inserts a comma after eats in the description “Eats shoots and leaves.”37

Several popular image macros raise such questions effectively, too. The series of macros pictured earlier might themselves be viewed as deformative critique, particularly in responding to the tendency to abandon punctuation discussed at the beginning of the introduction, which as these artifacts suggest, we might more accurately rethink as a tendency to misuse punctuation.

These images humorously play with punctuation, demonstrating the ways in which slight misuses of marks can drastically change intended meaning, continuing a popular cultural investment in punctuation that was evidenced by the big success of Truss’s 2003 best seller. Due to the digitally generated and circulating nature of these macros, they inscribe an added dimension of self-reflexivity on the shifting uses of language that coincide with digital contexts. While they tap into fears older generations have about abuses of the English language, at the same time, through their very reliance on a popular form of new media, they seem to acknowledge the possibility that rather than viewing this situation as symptomatic of the deterioration of culture, we might instead consider it a shift, a less judgmental view asserted by this book’s title.

This book offers multiple, but complementary, views on “shift” as a concept. One approach to viewing this shift is to understand the writing in this book itself as a performance of a textual shift, as an extended exercise in deformative criticism. In effect, I read culture as a vast media-textual fabric and isolate, or to recall Flusser’s metaphor, fish for, a series of punctuation marks from it. What, I ask, might these textual isolations teach us about their broader contexts: culture and everyday life? This line of inquiry certainly has its place; it favors knowledge generated by associative logics, close reading, formal observations and speculations, intuitions and counterintuitions, historical coincidences and contingencies. It creates a space that allows us to think about the sets of relations at play with typographical structures in cultures of writing and how we might read similar sets of relations in other nontypographical contexts. But it does not aim to forge a repeatable path, or to launch a definitive argument about contemporary society. While the period is examined in detail in the next chapter, the punctuation mark that guides my thought across the chapters is more the ?, not the . or the !.

The book’s chapters can each be read individually and out of order, and readers should be able to enter at multiple points with hopefully little confusion. However, the chapters are also organized in a sequential order, posing a sustained question that itself shifts, closely analyzing punctuational trajectories, allowing us to read a series of textual shifts related to new media and the aesthetics of digital screen cultures.

On one level, one can read the movement of the book’s chapters as enacting a sustained, playful reference to the literal shift function of a computer keyboard — a key that, when pressed in conjunction with any alphanumeric or punctuational character’s key, achieves an alternative inscription effect, often capitalizing a given letter or transforming a number into a punctuation mark. The shift key is, after the space bar (which itself inscribes the originary mark of punctuation — empty space), the largest key on the computer keyboard, often appearing in two symmetrical positions. Quite literally, the shift key makes the electronic writing of punctuation possible.

The second chapter begins with the period: the most elemental of marks, which gets its own place on the QWERTY keyboard, just to the right of the M and the comma keys. Interestingly, as I will soon explain, in the original design for the typewriter’s — which was later borrowed for the computer’s — QWERTY layout, the period was supposed to occupy an even more central position, where the R currently resides. But it was subsequently moved so that all the letters of TYPEWRITER could be found along the top row. Embedded within our contemporary keyboards is this earlier history of punctuational shift.

Thus we start with a mark whose inscription does not require the use of the computer’s shift key but that represents a historical shift in design that positioned punctuation in general on the sides of our technological interfaces. The next chapter follows trails of parentheses, symmetrical pairs of punctuation marks that work together and both of which rely on the shift key for inscription, in and out of new media. The fourth chapter takes Twitter’s hashtag as a starting point to think about the history of the # symbol, the sign alternately known as number, pound, hashtag, octothorpe, and even by some (somewhat mistakenly) as the musical sharp sign. This character, dependent upon the shift function as well, is, however and importantly, not conventionally or in a literary sense understood to be a mark of punctuation. Rather, this character, like the equal sign, could be understood as what I refer to as loose punctuation. By reading the #’s media history within the book’s larger framework, however, I in effect aim to “shift” our very understanding of what punctuation is and can be to include such “loose” characters. This move is productive because this shift is paralleled throughout the logic of digital culture itself, and thinking on its borders will allow us to refine our understanding of the ontological parameters of punctuation in the present context. It seems clear to me that today the # is a form of punctuation and, moreover, that this is significant.

In order to understand the broader significance of punctuation’s own shift and relational logics beyond the written text and into the images of our visual culture, I draw on several examples from cinematic media to help illustrate this more culturally pervasive shift. Methodologically, this offers the advantage of extending questions that might normally be exclusively of interest to literary scholars and bringing them more centrally into the purview of film and media scholarship. Cinematic media in particular pose further conceptual advantages. As many film theorists have noted, film is in effect a combinatory media form, which is not to subscribe to claims that it is a superior medium, but simply to say that it formally integrates literature’s narrativity and temporal unfolding with photography’s visuality.38 Since a critical component of this book’s approach to punctuation is that, in the context of the emergence of networked computing especially, punctuation indexes a distinct reconfiguration of image and language, cinematic works offer an opportunity to draw attention to both of these punctuational dimensions at once and to their changing relationships with each other.

It is important to acknowledge that punctuation’s digital dimensions are being explored quite provocatively in a range of electronic writing practices, most notably in the domain of codework, practiced by artists and writers like Florian Cramer, John Cayley, Mez, Talan Memmott, and Alan Sondheim, as has been studied by scholars such as Rita Raley, Katherine Hayles, and Cayley himself.39 In order to demonstrate how in the digital age punctuation’s reach extends beyond literary practices, I take as an assumption that it is worth devoting attention here to other media forms, where punctuation has been less studied and foregrounded. Moreover, I hope the book’s cinematic throughline will be useful to those invested in literary concerns, offering insights about the literary by virtue of its being articulated in and represented ekphrastically by another media form — one that is arguably more constitutive of the fabric of popular culture and thus might represent more widespread ways of thinking about and culturally imagining textuality.

Thus in each chapter that follows, the book throws the textual shift it explores into perspective via a cinematic lens. The cinematic work examined inscribes the mark in question on a literal level, but on an even deeper level also enriches a consideration of punctuation’s particular cultural logic that each chapter parses out. Viewed together, the specific movies — Adaptation. (directed by Spike Jonze, U.S., 2002), Me and You and Everyone We Know (directed by Miranda July, U.S., 2005), and I Love Alaska (directed by Sander Plug and Lernert Engelberts, Netherlands, 2009) — form a parallel picture of a shift toward the digital that mirrors the punctuation marks I read them in relation to (the period, parenthesis, and hashmark, respectively). Coming from three distinct historical points in a decade that saw rapid transformations in the influences and uses of digital technologies within popular culture and media, these films index a shifting digital consciousness that begins with anxieties over the dot-com crash that opened the decade and moves toward anxieties about new ways that digitally mediated technologies reshape human intimacy, privacy, information, consciousness, and creative expression — issues whose stakes and consequences only seem to be increasing in magnitude as we settle into the mid-2010s.

Formally and thematically, each film’s own relation to the idea of the digital itself also increases as the book proceeds. Adaptation., the second chapter’s cinematic text, upon first consideration might seem to be a postmillennial analog anomaly. The film was shot on 35 mm film and features a main character — a screenwriter named after the film’s own screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, played by Nicholas Cage — who types his screenplay on a typewriter. Yet Kaufman is tormented by a fictional twin brother also played by Cage, and thus the digital creeps in as an anxiety: materially, as the actor’s ability to act with himself is made possible by digital trick effects in postproduction; and narratively, as I will argue, one can read the film allegorically as representing broader anxieties about the digital in the cultural context of dotcommania ideologies.

If in Adaptation. the digital is merely a threat the film tries to keep under control, in Me and You and Everyone We Know there is no turning away from it, and Miranda July, like Adaptation.’s Kaufman character, maintains a semi-autobiographical presence in the movie. The movie is shot digitally and directly thematizes digital media and art, whimsically yet thoughtfully approaching the kinds of intimacy, connections, and creative possibilities new media lend to contemporary life while also interweaving these digital themes — and in a sense even interrupting them — with a tender, old-fashioned romantic comedy. This narrative strand centers on a love story between two young adults who meet in a mall’s shoe shop, and the couple’s greatest mark of technological advance is July’s occasional use of a cell phone to reach her shoe clerk love interest on a landline. July’s film, I argue in the second chapter, moves parenthetically in and out of old and new.

The book’s cinematic infrastructure becomes most fully digital in the third chapter with its consideration of I Love Alaska, an online episodic mini-movie about an AOL search leak. Distributed online, about the Internet, and with a “script” made only of search queries, this movie’s documentary ethics raise questions about the ways in which we have become posthuman data bodies, defined by our identification numbers and dependent upon search epistemologies for navigating contemporary life. These readings thus provide a cinematic throughline to the book’s larger argument, reinforcing and distilling the claims I make about shift, punctuation’s cultural logic, and digital media, while at the same time figuring as textual counterpoints to them, posing their own complicated questions about narrative, storytelling, postmodernism, and life in our digital era.

Outro: Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?

To stage some recurring themes that surface in the book’s attention to punctuation’s role in visual culture via cinema, one final illustrative example provides an opportune transition into the next chapter. Michel Gondry’s Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? (France, 2013) is an animated conversation between an unlikely pair: the filmmaker and renowned linguist, philosopher, and activist Noam Chomsky.

Gondry filmed two conversations with Chomsky at MIT in 2010, which he presents embellished with beautiful, hand-drawn animations made with neon-colored Sharpies, illustrating and interpreting the stories and ideas Chomsky discusses on the soundtrack. Framed as an effort to race against time and record meetings with Chomsky while he is still alive and well (he is in his early eighties at the time of filming), Gondry focuses their conversations on the philosopher’s personal life and his linguistic and scientific theories, rather than politics, about which Chomsky is known to be equally if not more publicly vocal. The title of the film refers to a discussion between the two that closes the film, about Chomsky’s theory of generative grammar. It involves the phenomenon of children intuitively knowing how to construct a question out of a sentence in a complex, counterintuitive way. So they consider an example: to transform the sentence “The man who is tall is happy” into a question, it is necessary to move the sentence’s second “is,” not the first, to the front of the formation: “Is the man who is tall happy?” rather than “Is the man who tall is happy?” Children always know this, suggesting that to some extent complex linguistic rules appear to be biologically hardwired in our minds.

Interestingly, in the conversation this example starts with, Gondry provides Chomsky with a slightly different sentence to use: “A man who is tall is in the room.” Chomsky, however, innocently changes it to “The man who is tall is happy” in explaining his theory. The slight difference is suggestive of the ways in which Gondry and Chomsky, despite their best intentions and generous engagement with one another, do not always quite follow each other (though usually as Gondry humbly presents it, it is he who struggles to express himself clearly to Chomsky). Their subtle miscommunications, and their effort to work past them to understand each other, become one of the movie’s charming themes, a fascinating effect of watching them communicate. This simultaneous connection and disconnection is very effectively captured by Gondry’s frame-by-frame animations, which assiduously try to keep up with Chomsky’s fast-moving associations and deep knowledge, rendering Chomsky’s ideas paradoxically abstract yet concrete.

Among the most recurrent images Gondry draws in the film is a question mark, which has the effect of both referring to the more specific linguistic phenomenon of the syntax of the question posed in the film’s title but also undoubtedly becoming a more general representation of the mood of the encounter between Gondry and Chomsky — and of Gondry’s own modest positioning of himself in relation to the great mind of the philosopher. Over the course of the film, hundreds of question marks move through Gondry’s drawings. They proliferate around the words of the film’s title in one of the film’s closing sequences, and in another (pictured in Figure 6b), we see a question mark climbing up repetitions of the word WHY, spelled out on their sides and ascending like stairs. Question marks are often not surrounded by other words and letters at all, figuring as characters operating on their own. For example, in another sequence, Chomsky discusses psychic continuity and then the importance of again being willing to be “puzzled by what seems obvious,” as the earliest scientists were, such as not taking for granted why a ball goes down rather than up. He says about the simple question “Why?”: “As soon as you’re willing to ask that question, you get the beginnings of modern science.” In an abstract visual sequence accompanying this, a three-dimensional, neon-blue question mark becomes connected to another block-faced, neon-blue question mark on its side and behind it, until there are over fifteen identical question marks, each connected to the others and extending in different directions on the black screen. Eventually about a dozen almost parallel squiggly orange lines with pink dots on the end repeatedly run from the left of the screen to the right, through this question-mark configuration. To the spectator, Gondry then laments in response to Chomsky’s discussion that he did not express himself clearly enough: “Once again I had posed my question the wrong way.” Gondry had been curious to know whether humans are hardwired to build societies (“cities, art, cars, and so on”) the way bees construct hives, but Chomsky had apparently not realized that is what the filmmaker was trying to ask.

Adam Schartoff notes in an interview with the filmmaker, connecting Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? to Gondry’s previous films, “It’s as though you’ve almost created a language problem for yourself, and that you’re making movies in another language in a way, and you find this other, third language almost — it’s like an alternative reality component to almost every film you’ve made.” Gondry seems intrigued by Schartoff’s observation, thinking back to Chomsky and his 2005 film Block Party with Dave Chappelle in particular: “in both cases, it’s hard for me to understand them, it’s hard for them to understand me, so we have to connect on a different level, and that really describes this level.”40