Digital Shift: The Cultural Logic of Punctuation (2015)

3

# Logic

Hashtaggery

The preceding chapter marks a transitional parenthesis in this book’s larger account of textual shift, with the parenthesis’s grammatical, symmetrical, and in-between allure. Regarding punctuation and digital textuality, too, it is transitional within this book’s flow. Unlike the period examined before it, the parenthesis relies on the computer’s shift key for its inscription. In this chapter I turn our attention to a character that relies on the shift key as well but that, unlike the period and the parenthesis, is less strictly a punctuation mark in the conventional sense, though some historical accounts in this chapter’s purview have explicitly and implicitly referred to the # symbol as punctuation in suggestive ways. Just as the preceding chapters mobilized characters as reading lenses for comparative media analyses, this chapter also examines a string of texts, technologies, and phenomena that the # symbol calls our attention to and that in turn expand our understanding of the cultural logic of the symbol — and ultimately of punctuation more generally. Precisely insofar as the # mark straddles conceptual boundaries of punctuation more than the period and the parenthesis, this chapter will allow us to home in on and conclude the book’s broader inquiry by interrogating and refining our understandings of what punctuation even is, particularly as it intersects with and is informed by media history, visual culture, and the digitization of the world.

It seems only appropriate to pick up after the book’s parenthesis with a character (of the nontypographical sort) who was central to the ending of the preceding chapter on the period: Susan Orlean, the New Yorker writer who penned The Orchid Thief, the basis for Adaptation. Shifting focus from orchids to the hashtag, she published a piece titled “Hash” on the topic in June 2010 for the magazine’s blog. She muses at the outset, “The semiology and phenomenology of hashtaggery intrigues me.” Orlean observes in the piece with trademark New Yorker wit and cultural insight,

Hashtags have also undergone mission creep, and now do all sorts of interesting things. Frequently, they are used to set apart a commentary on tweets, sort of like those little mice in the movie “Babe” who appear at the bottom of the frame and, in their squeaky little mouse voices, comment on what you’ve just seen and what you’re about to see. A typical commentary-type hashtag might look like this:

“Sarah Palin for President??!? #Iwouldratherhaveamoose”

This usage totally subverts the original purpose of the hashtag, since the likelihood of anyone searching the term “Iwouldratherhaveamoose” is next to zero. But that isn’t the point. This particular hashtaggery is weirdly amusing, because, for some reason, starting any phrase with a hashtag makes it look like it’s being muttered into a handkerchief; when you read it you feel like you’ve had an intimate moment in which the writer leaned over and whispered “I would rather have a moose!” in your ear.1

Orlean’s blog contribution productively begins to critically unpack the unique tone that belongs to hashtag-preceded tweets, a form of textuality that has spread far beyond Twitter and seeped into all forms of writing, and even into speech and music — culminating in a popular subgenre of hip hop, “hashtag rap” and a pattern of speech frequently embraced and parodied by Jimmy Fallon in late night television. Orlean’s humorous comparison of tweets to Babe’s mice recalls the “audience within the text” that we considered in the previous chapter’s discussion of the laugh track’s parentheticality. Indeed, the “whisper” of a tweet that Orlean describes in many ways suggests a striking affinity with the parenthetical, where both instances of inscription articulate an author’s personal and often humorous response to the more official language that precedes it. In this sense, the hashtag and the parenthesis both serve to set textuality off, indicating to the reader the presence of a personal reflection from the writer.

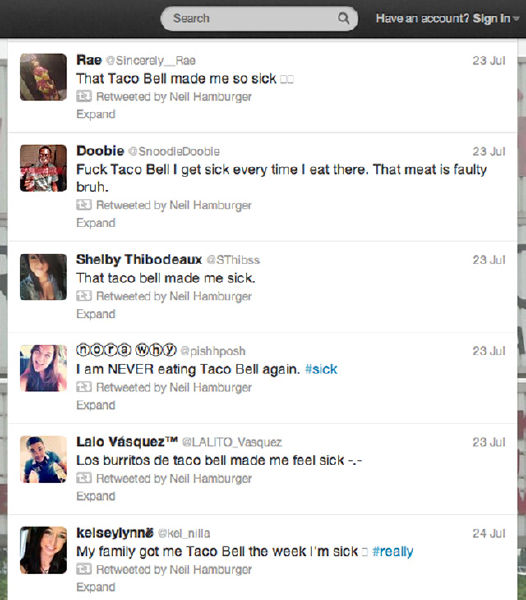

But the difference between them is crucial. The intimate, handkerchief-muffled tone of the tweet is projected in a forum that by its nature is anything but intimate. It is public, and in practice the hashmark makes the message it accompanies accessible to a large audience of friends, followers, and digital strangers. The hash’s tagging function is a key characteristic of the mark’s shifted textual circulation in digital contexts. The symbol indexes whatever phrase follows it alongside all other tweets that contain the same phrase, allowing users to group and locate information that belong to a common topic, theme, or mood —hence facilitating everything from the recent trend in marketing and quantitative studies to conduct “sentiment analyses” of the networked community at any given moment to the ability of comedian Gregg Turkington’s Neil Hamburger character to retweet hundreds of messages about Taco Bell food poisoning from a myriad of users and dates at once to create a comedic but also trenchant glimpse into American society.

Figure 20. Taco Bell food poisoning joke on Neil Hamburger’s Twitter page

The American Dialect Society voted the word hashtag to be 2012’s “word of the year,” signaling the pervasiveness of the term not only in Twitter but across the Internet and in everyday life. Voicing widespread sentiments, Lindy West writes of the mark’s hold on popular culture, “Just a couple of years ago, our little friend # was nearly irrelevant, relegated to the lonely domains of foam fingers (we’re #1!) and robocalls (press # for more options). But these days, along with its boyfriend @, # is leading the charge in the Twitter Revolution (#SorryISaidTwitterRevolution). Hashtags have changed the way we think, communicate, process information. In all likelihood you’re hash-tagging something right now. # is everywhere. # is inside you.”2

A particularly instructive moment occurred in early 2013 when France’s Commission générale de terminologie et de néologie officially banned the English word in official documentation and replaced it with mot-dièse, the French equivalent for “sharp word,” referring to the musical sharp key’s sign. The commission’s objective, since 1996, has been to preserve the French language’s purity, largely by keeping English words out of the language as much as possible. As such, one of their tasks is to encourage “the presence of the French language on social media networks.”3 Though the effort to not passively step aside and watch as global English imperializes the world’s other languages is admirable, it is also worth tuning in to the skepticism registered by those who have suggested that this political commission’s energies are misguided and out of touch. Will official banning of the language in documents truly have sway over vernacular that has already existed for several years? Does the slightly inaccurate translation, since the musical sign and the hashtag slant in different directions, demonstrate a disconnect with digital culture? Perhaps more crucially, to what extent is such an effort denying the reality of Global English and the way it constitutes and structures the languages and logics of networked communication? That a national governmental organization went to the trouble to ban the use of the word hashtag indicates the extent to which the phenomenon is “everywhere” and “inside” us.

To write that the symbol is “inside you” is suggestive of the manner in which the # sign harnesses a cultural logic, of how it represents a way of thinking that has deeply penetrated cultural consciousness. One might reflect a bit further on the ontological nature and phenomenological consequences of this strong impact. Does it mean that we now think in keywords — and that we previously did not? Does expressing our thought in keywords or hashtag punchlines come at the expense of other forms of expression that have different dimensions and textures of experience? It might at first seem tempting to associate the # sign’s cultural hold with a bad turn — a decline, a lack of sophistication, a loss of literary complexity, or even of literariness itself.

“#Hashtag,” the most popular skit in the history of Late Night with Jimmy Fallon, as measured by its online viewership with over 23 million views in its six months on YouTube as of early April 2014, offers an illustrative mise en scène of these cultural anxieties. This skit imitates — and exaggerates — the incorporation and interpenetration of social media discourse into everyday discourse. Fallon and regular guest Justin Timberlake perform a conversation in which hashtag discourse feels like it outweighs nonhashtagged discourse, so that, for every phrase spoken, there seem to be two or three hashtags the performers offer. The effect of this is, of course, irritating, as confirmed by Questlove’s closing quip, telling them to “hashtag shut the F up.” The skit’s overwhelming popularity certainly indicates that viewers identify with this irritation. Indeed it was so popular that Fallon did a very similar sequel to the skit in his first week hosting The Tonight Show a few months later with guest Jonah Hill, which featured a cameo by Martin Scorcese.

Figure 21. Jimmy Fallon and Justin Timberlake making hashtag finger gestures on Late Night with Jimmy Fallon (September 2013)

Both scenes’ ratios of tags to nontags register anxieties about the impoverishment of communication — how meaningful statements and thoughts now seem to be drowned in a sea of keywords, accompanied by a shortened attention span and a paradoxical mode where people seem connected but not really — one strand of conversation hardly builds on the previous one, and rather language just seems to accumulate, go nowhere, punctuated and emphasized by the finger pound, crossing the index and middle fingers of both hands to visualize the hashmark. The deterioration of the conversation in the original skit is most fully realized when the final exchange between Timberlake and Fallon is just composed of sounds, nonwords to the tune of a Missy Elliott song, interrupted by Questlove, with his own finger pound.

Figure 22. Martin Scorcese making a cameo (and a hashmark) on a reprised hashtag skit on The Tonight Show (February 2014)

These skits provocatively lay bare, to quote Marquard Smith’s recent claim, that in our current moment, “all content has become largely irrelevant. What matters,” he writes, “is not what is gathered, arranged, and transmitted, but how such gathering, arranging, and transmitting works. ‘What’ is supplanted by ‘how.’ ”4 The Fallon-Timberlake exchange and particularly discussions about it illustrates this perfectly: cultural commentators and various casual conversations I have overheard about it in public do not mention what Fallon and Timberlake actually talk about — cookies, Mona Lisa, Miley Cyrus, or Orange Is the New Black. Rather it is a vessel for metadiscourse, for talking about how we talk with hashtags in popular culture. This is why the skit resonates.

A regular viewer of Fallon’s shows might find that the host’s critique of this habit is undermined by his frequent use of the hashtag as a means to engage with the audience: every week on Late Night, for example, he orchestrated the “Hashtag Game,” for which he would coin a hashtag and invite home audiences online to contribute the preceding statement to which the hashtag belonged, reading a handful of his favorites on air. However, it makes sense to read this as consistent with the Timberlake skit’s critique, as an attempt by Fallon to cultivate thoughtfulness about how to use the mark properly and wittily. Indeed, Fallon is often admired and distinguished above and beyond his late night peers for integrating digital trends and social media into television.

Contributing to the chorus of conviction that we are deeply under the influence of the symbol found across popular texts to more highbrow cultural criticism, Piper Marshall writes for Artforum,

The temperament of our generation can be summed up by the hashmark. If the ‘90s were full of “quotation marks” indicating irony, a decisive sarcasm and a distance from the opinion of norms, our current climate is dominated by pithy punch lines that summarize the solipsist’s always already uploaded narrative. The hashtag is the redemption of Internet statements — written to be read by everyone you know, obviously. Until they are recycled via a chaotic circuit of retweets, reposts, and reblogs, eventually rendered as vapid as that ubiquitous Facebook prompt: “What’s on your mind?”5

Marshall suggestively takes as an assumption that the hashmark is punctuation, situating its affective trajectory as following on the heels of another generation’s signature marks — 1990s’ quotation marks —foregrounding their analogous inscription of cultural zeitgeist.

One might note that the four fingers used to figure the hashmark, as the five performers in Fallon’s two hashtag parody skits all gesture, are the same pairs of fingers used by speakers to indicate quotation marks. In her 2003 book Quotation Marks, which is very much about and symptomatic of the prior decade’s cultural fascination with quotation, Marjorie Garber discusses the tendency to “flex the first two fingers of each hand, miming the look of (American-style double) quotation marks on the page,” observing that “the two-finger flex has become conventional rather than strictly mimetic, a sign of quoting rather than a quote-sign.”6 Her subsequent reference to this gesture as “digital quotation” is a useful reminder of the close etymological and historical ontological relationship of fingers-as-digits, our bodily counting organs, to the digital, the numerical, computerized infrastructure of our media systems. Both hand movements notably involve the two index fingers, quite literally figuring a shift in digital indexicality, where the index (finger) no longer points to a referent but in fact gestures to an absent, metaphorical text.

This continuity from quotation marks to hashmarks is surprisingly generative to consider. Social media’s hashtags have in a sense become repositories of quotations. Think for example of what happens when a celebrity dies. Various other celebrities tweet their responses and condolences, and journalists then draw on these remarks, turning them into quotations used in longer-form obituaries. The same goes with reportage of current events: politicians’ tweets become sound bytes used to texture coverage of current events and in effect construct historical narrative. In other words, a distinctly late-twentieth-century cultural fascination with quotation, which was just as much about truth and authority as an ironic skepticism in them, finds its social media outlet in Twitter, where these same issues are still felt but transfigured. Namely, the voice and position of authority have become diluted, the iterations of the story have been amplified and more quickly replaced by the latest trending topic — indexed by hashmarks.

To read the quotation mark as a predecessor of sorts to the hashmark thus affords a useful opportunity to remember the historical and cultural contexts that it seems so often tend to be elided in conversations about new media that focus on the nowness of the present, or what Wendy Chun calls the “enduring ephemeral.”7 Marshall’s comments — emphasizing “retweets,” “reposts,” and “reblogs” — also point to the impossibility of making sense of the hashtag’s significance outside of the context of textual proliferation. According to Marshall, the marks offer the promise of the possibility for our tiny words to seem significant and clever when they might otherwise seem lost in an endless flow of discourse. This significance relies on being indexed and on the possibility of being found.

If periods and parentheses draw attention to the proliferation of textuality in digital contexts, then hashmarks continue to do so, while at the same time, like the others, demonstrating how this proliferation is managed bypunctuation marks as well. Indeed, this managerial feature is one of the striking roles the period and the parenthesis play in digital culture — from the period’s structuring of domain names to parenthetical bibliographic references. If in print culture punctuation helps manage semantically, clarifying textual meaning, then in digital culture there is a distinct shift whereby punctuation now helps manage more syntactically. While punctuation in human languages certainly has syntactic functions, the important distinction is the loosening of its semantic functions. Semantic displacement represents a more general textual shift that punctuation is metonymical for: to an informational, instrumental, and short-form computer-oriented textuality from a narrative, expressive, and long-form book-oriented textuality.

The hashmark’s popular use on Twitter, a social microblogging website composed of updates famously limited to a maximum of 140 characters, provides an opportunity to further condense the most salient topic of an already short message into a keyword, a phrase, or a string of keywords and phrases. In this sense, the hashtag represents what is arguably the single most pronounced feature of new textual practices: the brevity of communication and expression.

This textual condensation is further highlighted by the elimination of spacing between words that come after a hashmark. Spacing is itself ontologically and historically bound to punctuation. As pure but deliberate textual emptiness, spacing could be considered punctuation’s most basic manifestation. Writing before around 1000 AD was conventionally in scriptio continua, meaning that texts were presented in a continuous stream of letters, with no word separation or punctuation. As M. B. Parkes explains, text presented in this style “required careful preparation before it could be read aloud with appropriate pronunciation and expression. Rendering a text in scriptio continuaproceeded from identification of the different elements — letters, syllables, words — through further stages to comprehension of the whole work. Reading at first sight was thus unusual and unexpected.” He elaborates further,

The merit of scriptio continua was that it presented the reader with a neutral text. To introduce graded pauses while reading involved an interpretation of the text, an activity requiring literary judgment and therefore one properly reserved to the reader. In ancient Rome readers of literary texts were mostly a social elite, whereas full-time scribes were usually freedmen or slaves (Atticus kept slaves to publish Cicero’s work). Quintilian observed that many things to do with reading could only be taught in actual practice: when a pupil should take a breath . . . , at what point he should introduce a pause into a line of verse . . . and where the sense ends or begins. . . . All of these are situations which we would expect to be indicated by punctuation as we understand it now; then, a reader had to analyse the phrasing of a text before he could read it properly.8

Thus the return to the elimination of textual space that occurs with increasing frequency in digital culture (routine in web addresses for example, but culminating par excellence in hashtags) foregrounds provocative affinities with ancient textual practices, bringing into focus the relationships among literacy, clarity, social status, textual neutrality, and perhaps most interestingly — on an ontological level — a reintroduction of an increased level of interpretation that takes place while reading. To what extent, for example, does being able to read a tweet depend on a technological literacy that has been cultivated to know how to insert pauses between words? The brevity of a tweet is mostly not comparable in terms of textual complexity to a story conveyed on ancient scroll, but such a comparison is worth considering if only to weigh the nature of the continuities and discontinuities digital textuality presents against previous forms of writing. Like scriptio continua, the tweet demands mental activity of separating on one’s own to make sense.

Of course with hashtagged script, unlike scriptio continua, nonspacing coexists with spacing. As such it is discourse that visibly inscribes the simultaneity of machine and natural languages. One could thus read the elimination of spacing in the digital context as registering an antagonism between the human and the machine, a result of the human being forced by technical protocol to confine text to a limited space. Condensation becomes an almost frantic response to pressure, cramming in what one needs to say while one has the chance, without taking a breath, so to speak.

If the management of textual proliferation and the brevity of digital communication practices mark two primary features composing the cultural logic of the hashmark, then a third central feature of its logic could be conceptualized as a changing multidimensionality of language throughout digital textualities, characterized by a simultaneous interaction of the horizontality of human languages with the verticality of computer languages. The intersecting horizontal and vertical lines of the symbol could be understood to visualize this condition. On one hand, an overwhelming number of Internet users know how to use the mark. Yet on the other hand the hash symbol’s function of indexing metadata, of collecting and hyperlinking all other expressions that contain the word or phrase tagged, points to a computational process that the majority of us understand the effect of but which depends on our reliance upon a series of computational operations that are largely invisible, inscrutable, and too technical for the majority of Internet users to understand — or to want to understand.

Viewed from a more distant vantage point, this procedural logic represents an extension of the principle of apparatus theories of cinema that were popularized (and more recently popularly criticized) in 1970s film theories inspired by a particular confluence of Marxism, psychoanalysis, poststructuralism, and feminism. One’s encounter with a website such as Twitter, like one’s encounter with a given cinematic text, is facilitated by a range of technical processes invisible to the eyes and “smoothed” over; these processes facilitate experiences with the media interface and our psychological immersion into its platform. (Or, in describing the Internet, “immersion” might be better substituted by passing, browsing glances.) Indeed, if film theory’s point was that our encounters with cinema are shaped by ideologies inscribed in the structural situation of the cinema and the material, technical components that constitute cinematic spectatorship, then so too one could think of the ways in which our encounters with new media texts are shaped by ideologies inscribed in computing systems and software.

In the more specific context of digital textuality, the operative principle of the hashmark can be viewed as exemplary of what Espen Aarseth has identified as the “dual nature of the cybernetic sign.” Mobilizing semiotic vocabulary to describe this duality, Aarseth identifies the scripton as designating the sign’s surface image and texton as referring to its underlying code.9 Implicitly or explicitly, a range of observations by textual scholars echo the logic of this distinction, whose contradictions are forcefully channeled into the hashmark’s singular character. N. Katherine Hayles, for example, coins what could be reappropriated as the catchphrase for this situation in arguing for media-specific analysis: “print is flat, code is deep.”10 Though Hayles means to draw attention to the differential nature of the printed page and the electronic text, one might also make sense of this difference as constituting a differential dimensionality within all digital texts, as they remain visual like the printed page but contain an added, “deep” dimension of code.

Alexander Galloway pinpoints this logic of the digital inscription in his response to Wendy Chun’s reflections on software and ideology. He asserts, “Language wants to be overlooked. But it wants to be overlooked precisely so that it can more effectively ‘over look,’ that is, so that it can better function as a syntactic and semantic system designed to specify and articulate while remaining detached from the very processes of specificity and articulation.” “This,” he goes on to explain, “is one sense in which language, which itself is not necessarily connected to optical sight, can nevertheless be visual.”11 Galloway thus suggests that the digital situation is one in which language looks at us — we in a sense are the objects of visual culture, of the text’s gaze — in a structural inversion of cinematic apparatus theory. This potential is perhaps most fully realized when one stops to think about the highly technical and legal language of agreements on applications and software we sign off to with virtual signatures by clicking “accept” in order to become “users.” This language, too, we could surely say, wants to be “overlooked” to “look over” us. The “language” one then inputs on popular social media websites like Facebook, via status updates, because we have probably not fully thought through the consequences of these agreements if one even does take the time to read them, provides endless data for intelligence agencies and corporations who use personal information for monetary gain and social control.

One could articulate the quality of the textual condition that I am describing as follows. If Marquard Smith claims that how today supplants what, I would slightly revise this formulation: increasingly, that supplants what. We know that the system works and we know how to use it, but we don’t know how it works. The formulation usefully posits a replacement of a different linguistic order: rather than one question replacing another (from what to how), that suggests a uniquely removed relation to knowledge, where we do not question it — perhaps the question mark is, as Michel Gondry’s Is The Man Who Is Tall Happy? implied per the book’s introduction, not digital after all. Similarly, we know that information is accessible via the Internet, but we do not know the actual information it holds without it. Alongside social media relatives like the Google search and the Facebook status update, the Twitter hashtag represents this new relation to information, knowledge, and memory, part of what Bernard Stiegler would characterize as the “informaticization” of knowledge, whereby digital media’s “memory industries” are supplanting the primacy of human consciousness — and even “life itself.”12 We do not need to remember details, we only need a keyword to lead us through a chain of links and to the specific details that we can browse through, doing our best to determine what information we need or want and what information is disposable. The cognitive practices associated with this have been studied widely and seem to characterize a significant shift in the life of the mind in the “information age.” Information moves from being stored in our minds to being stored in our machines, while we refine our skills for searching, indexing, and knowing where to find stored data. The full extent of the ideological consequences of this shift — and the exact extent to which it characterizes a shift — remain to be witnessed and understood. Our fingertips, typing on our keyboards, mediate our access to knowledge.

One of the most provocative theorists to discuss and forecast this situation is perhaps the Czech writer Vilém Flusser, who presciently observed the emerging historical consequences of computer memory upon members of a computerized society. Consider for example his remarks in “The Non-Thing 2”:

Until quite recently, one was of the opinion that the history of humankind is the process whereby the hand gradually transforms nature into culture. This opinion, this “belief in progress,” now has to be abandoned. . . . The hands have become redundant and can atrophy. This is not true, however, of the fingertips. On the contrary: They have become the most important organs of the body. Because in the situation of being without things, it is a matter of producing and benefiting from information without things. The production of information is a game of permutations using symbols. To benefit from information is to observe symbols. In the situation of being without things, it is a matter of playing with symbols and observing them. To program and benefit from programs. And to play with symbols, to program, one has to press keys. One has to do the same to observe symbols, to benefit from programs. Keys are devices that permutate symbols and make them perceptible: viz. the piano and the typewriter. Fingertips are needed to press keys. The human being in the future without things will exist by means of his fingertips.

Hence one has to ask what happens existentially when I press a key. What happens when I press a typewriter key, a piano key, a button on a television set or on a telephone. What happens when the President of the United States presses the red button or the photographer the camera button. I choose a key, I decide on a key. I decide on a particular letter of the alphabet in the case of a typewriter, or on a particular note in the case of a piano, on a particular channel in the case of a television set, or on a particular telephone number. The President decides on a war, the photographer on a picture. Fingertips are organs of choice, of decision.13

Flusser conceptualizes a non-thing as that which cannot be held by the hand, and so in a computer-based society, the information contained within our machines is untouchable and non-thing. He argues therefore that we are increasingly “without things.” While some of his remarks stand to be complicated by a more nuanced understanding of digital media’s material conditions and coded infrastructures, Flusser’s comments nevertheless register the importance of attending to what one might think of as the surface effects of digital media, configured in the interactions of materiality, the body, keys, symbols, and computing technologies. Flusser’s early interest in such surface effects are particularly relevant (and also poetic) for understanding a punctuational symbol like the hashmark, a character that appears on buttons millions of people press everyday. What “happens existentially” when on our computers we hold down the combination of the shift and 3 keys to inscribe the # sign or when we scroll our mouse over a hashtag to click on it and uncover related themes? What “decisions” do we make?

The use of the shift key takes for granted, for example, a certain familiarity with the keyboard, insofar as in its current design, there is no intuitive means to discern that the characters written directly on top of the number keys are inscribed by pushing the keys in conjunction with shift. The current keyboard thus relies on a (relatively basic) socialization process and learning curve whereby one gets accustomed to “playing” it like a musical instrument, learning the correct combination of buttons to achieve desired effects. I call attention to this practice more for rhetorical effect than to offer definitive answers or claims about phenomenology and digital media, but these questions provide an opportunity to think comparatively and historically about various media forms, technologies, and their relationships: from the soundscapes created by musical instruments and the telephone through the letterscapes of the typewriter and the computer.

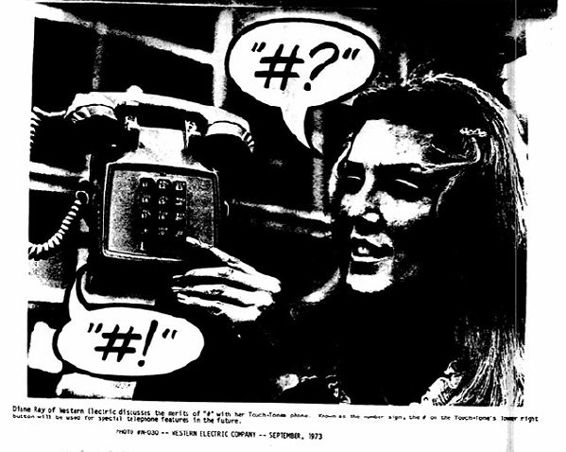

Indeed, Flusser’s comments here and elsewhere about textuality, design, the body, playing with symbols, and the necessity and significance of fingers pressing keys can form a transition to delve into another moment that more closely coincides with his own, staging a juncture of continuities and ruptures with the hash symbol’s present pervasiveness. The symbol’s logic can be radicalized by juxtaposing it with an earlier moment of “new” media — when the number sign was introduced to touch-tone telephones in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The Telephone’s Octothorpe

According to a Western Electric document on file at the Bell Laboratories archives, the company manufactured 6,700,000 # buttons in 1972 alone.14 This number of number signs is a useful reminder that the button and the symbol on it have substantial presence throughout the history of media technologies and their audiovisual cultures. Is it possible that the sign’s uses in previous technological contexts such as the telephone’s made possible a cultural context in which it could be redefined and popularized by Twitter? How and what, in other words, might the mark be able to illuminate about cycles of culture — how and when certain practices ebb and flow, how and when certain ways of thinking congeal and are reconditioned? As Flusser’s comparative perspective reminds us, we use buttons to make decisions on telephones and computers alike.

The operator’s recorded voice instructing the caller on the line to “press pound” is now a commonplace feature of our uses of telephones, but, of course, it was not always. A Bell Labs News article, “New Phone Buttons Offer Instant Banking, Cooking,” announces in March 1968 the Bell System’s plan to add two buttons to its touch-tone telephones “to get ready for the push-button world of tomorrow.”15 Until that point, their telephones contained ten numbered and lettered push buttons for dialing. The two new buttons introduced were of course the asterisk in the lower left and the number sign in the lower right of the keypad, sandwiching the zero, provocatively situating them as if they are nonsignifying characters like the zero, unlike numbers and letters with positive values.

At the time the buttons were introduced, they would have indeed seemed to be nonsignifying. As the article’s author explains, “For the time being, they have no function. But when some of the future TOUCH-TONE services become available, the two new buttons will be functional.” It would be too easy to equate the buttons’ nonfunctionality with nonsignification, however. Not only could the buttons be viewed as signifying nonfunctionality itself (which must be understood as distinct from nonsignification) but, more accurately, they signified the promise of innovation in an unknown future. The announcement proudly declares that “a businessman will be able to check computerized inventories of his merchandise, or a bank clerk can adjust accounts by tapping out information that his TOUCH-TONE set will feed into a centralized store of bank data.” Enthusiastically anticipating a future in which “many more custom-designed services will be available,” the author writes, “The two new buttons will be used to operate these new services. The shopping housewife, for example, might dial her home number and then push the asterisk button to start her electric oven.” The asterisk was of course never developed for “instant cooking,” but the two buttons did take their place as telephone keypads’ eleventh and twelfth buttons, taking on routine uses in various automated services on telephone calls.

One thus encounters a historically recurring assumption that punctuational characters serve as floating signifiers, easily adaptable to a range of situations in which designers and cultural innovators might wish to put them to use. The flip side of this semiotic flexibility is that their context-dependence also threatens their value, rendering them nearly ontologically void. However, a more specific phenomenon comes into play as well: as the marks become standardized into digital contexts, they are increasingly able to signify in isolation, thereby losing a semantic flexibility but gaining in return an increased visual mobility.

Moreover, we see here how the telephone’s potential is marketed to a wide audience, while drawing on heavily gendered discourses and expectations prevalent in the 1960s, imagining a male businessman or banker and a female housewife. One might think of the female operator’s voice that, as the sign’s function did historically develop, instructs callers to follow data commands by pressing the pound key, receiving and processing commands from an implicit male, helping make the service provided more efficient. Such a gendered dynamic is continuous with a long-standing structuring dynamic of women as professional “computers” or “programmers” since the very first computing systems were configured in the 1940s, which seamlessly extends into the continued imagination of the near future.16 In 2013’s Academy Award-winning Her (directed by Spike Jonze, as if to substantiate the presence of Adaptation.’s digital subconscious discussed in the first chapter), for example, Scarlett Johansson voices Samantha, the disembodied, Siri-like operating system with whom Joaquin Phoenix’s character falls in love. As so many critics have noted explicitly and viral parodies implicitly suggest, Her is resolutely not Him.

Figure 23. Her (directed by Spike Jonze, 2013): continuing the fantasy of the feminized machine

Figure 24. Introducing the number sign to the touch-tone telephone. Courtesy of AT&T Archives and History Center

The pound sign, in other words, could be contextualized within this gendered history of new media and punctuation, where the user tells the automated female voice that his command is complete, and she can take over, helping him get whatever he needs to get. Pressing the pound sign is an authoritative command, coming at the end of a data transfer, signaling the transmission’s completion, of often important and often private information, such as a password or a credit card number. The expectation of entrusting this kind of personal information with a feminized machine signals the ways in which, historically, women have been assumed to be more reliable and trustworthy than men.

In a note addressed in 1991 to William Safire on file at the AT&T Archives, which one could infer to be a direct response to his New York Times Magazine “On Language” entry “Hit the Pound Sign” of the same year, James Harris, a Bell Laboratories employee who was part of the team that introduced the two symbols to the touch-tone telephone, attempts to “put a bit of history on the record” about the # button. He explains that he and others at the Laboratories wanted to take “advantage of the fact that a touchtone ‘pad’ could be made to produce twelve different signals almost as easily as the ten that were in common use; the two extra signals (buttons) would be identifiers and punctuation for the data message.”17 Harris’s references to the symbols as punctuation usefully invite us to consider an expanded notion of punctuation that approaches a range of typographic symbols as behaving like punctuation, what I call loose punctuation, a conceptual invitation that the number sign instantiates. His use of the term might simply refer to the mark’s status as a nonalphanumerical character, but more than that, it also seems to register a sense of stopping and starting, of making data more readable, the way punctuation does in natural languages.

Harris recalls,

It was fairly easy to agree on the asterisk. . . . The great problem was the naming of the lower right button. . . . I would have preferred a simple dot or period, but our professional human-factors people held strongly that a dot could be confused with an asterisk and did not have sufficient distinctiveness. Way back then the many names we were aware of for “#” included octothorp(e) and lumberyard and, of course, pound mark and number sign. I was reluctant to go with the number sign (as I think of it) for three reasons: First, its name is a source of undesirable confusion. Second, for those people who do think of it as a number sign, the mind is pre-programmed to use it as a number sign; this may be different from the meaning in the particular protocol that is in use. Finally, thirty years ago I was deeply concerned with worldwide standardization, and I was concerned that some typewriters and keyboards around the world lacked the “#” symbol, thus denying their users the ability to type out the DIVA format.18

Given the symbol’s eventual frequent use as finalizing the transmission of a code, it is interesting that Harris wanted to make the key a period. He points to ways the two symbols are in a sense kindred spirits, where the pound is the period’s less linguistic cousin — since it does not have a linguistically traditional role as punctuation in human languages, something which, after Twitter, is now changing. Along these lines, the symbol repeated three times is also used to mark the document’s end in press releases or typed manuscripts.

The status and etymology of the term octothorpe itself is shrouded in a bit of mystery. Some writers claim that thorpe means village, and the symbol visually represents eight (octo) fields surrounding a village. Whatever its true origins, it seems to have been a jokingly and internally used nickname at Bell for the number sign. While some writers claim that the proper term for the sign is “octothorpe,” various employees in the telecommunications industry insist that the symbol’s name is emphatically not “octothorpe” but “number sign.”

A Western Electric news memo titled “A Story about #” seems to in fact be a memo that plays into the company’s internal joke about the sign. Its author references a quote from a nonexistent poem by Shelley B. Percey, “To a Number Sign”: “Hail to thee, blithe Symbol / Octothorp though never wert,” riffing on the line in the poet’s “To a Skylark”: “Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert.” The document also discusses a man, Charles Octothorp, who “decided one day to find a way of making his family name famous. His strategy was simple, but effective. He’d approach anyone with a Touch-Tone phone, stop, look closely and say admiringly: ‘Golly, that’s a remarkably handsome octothorp you’ve got there.’ ” After detailing an elaborate story about this man’s effort to deceive a gullible public, the author asserts to the reader, “When you encounter these people and hear their misusage, correct them. Tell them the truth — that the ‘#’ on the Touch-Tone button made by Western Electric is called a ‘number sign.’ ”19 This is accompanied by a cartoon illustration of a personified number sign with an angry face in the middle of repeating for a fourth time on a chalkboard the phrase “MY NAME IS NUMBER SIGN” (figure 25). Reading the exact tone of this memo is difficult: it does not read straightly as an instructional memo, nor is it entirely a joke. Somewhere between the two, it captures a certain geeky, technophilic attitude that nevertheless reflects a serious concern.

Figure 25. “MY NAME IS NUMBER SIGN.” Courtesy of AT&T Archives and History Center

For Harris, the stakes of naming the sign include historical accuracy, which would also seem to be the stakes inscribed in Western Electric’s documents, though in a roundabout way, via its perversion of history with the fictional character Charles Octothorp. One could thus read this fiction as playing provocatively with the symbol’s mysterious and debated history, and its ongoing shifting status in technological contexts.

It is also worth considering further what Harris refers to as “worldwide standardization,” since various international keyboards were not equipped with number signs. The sheer variety of terminology for the symbol speaks to the ways in which the number sign in particular registers national differences. It has been called the lumberyard in Sweden, the cross in Chinese, a hex in Singapore and Malaysia, hash in Britain, and pound and number in the United States and Canada, just to name a few. Harris’s concern was not treated as significant cause for choosing an alternate symbol, suggesting that those (Western) nations with the symbol on their keyboards would likely find themselves at a technological advantage when services provided by touch-tones would become more widespread. The recent decision by the French government to replace all official mention of the word hashtag with mot-dièse thus presents a provocative continuity with concerns over uses and naming of the symbol favoring English-language operating systems. In both cases, what might seem to be trivial worries over naming the symbol in fact channel broader concerns over what could be viewed as the spread of Global English that accompany the expanding empires encompassed by American technological services.

With this history put in perspective, one might begin to view the issues surrounding computing culture not as radically new but as continuous with recurring anxieties we can locate across multiple histories of new media that settle into standardized procedures as technologies become more everyday and less “new.” In this frame, the octothorpe/number sign/hashmark, like the period and parenthesis before it, becomes an instructive reading lens, which — as media historical text that is semiotically loose enough to be redefined with new technologies — is synechdochical. That is to say, it both ontologically shifts on a textual level and is also representative of much larger shifts under way in operating systems, media ecologies, and visual culture.

The Human behind the Number: I Love Alaska, Search Logic, and Narrative Desire

In keeping with the spirit of this book’s inquiry into the cultural logic of punctuation, which turns our attention not only to the ways marks circulate and indeed pervade visual culture, but to the ways thinking associated with these marks also circulates more broadly across media and culture — thus suggesting an even greater pervasiveness of punctuational logics and aesthetics — I conclude this chapter with an analysis of a text, I Love Alaska, which triangulates other technological iterations of the symbol, synthesizes its cultural logic, and in the process also returns us to the question of the broader status of semiotics in the digital age.

In particular, this work draws our attention to the # symbol’s role as a number sign and how it not only structures information in databases via its role as hashmark but organizes subjects as data bodies in digital ecosystems. The symbol-as-number sign also closes in on the very idea of the digital as that which is structured by discreet numbers. Isolated, the symbol, not itself a typographical number, helps throw the relationship between punctuation and numbers into relief, inviting one to speculate on the visualization of data in starkly different ways than how this topic is generally broached in digital humanities scholarship.

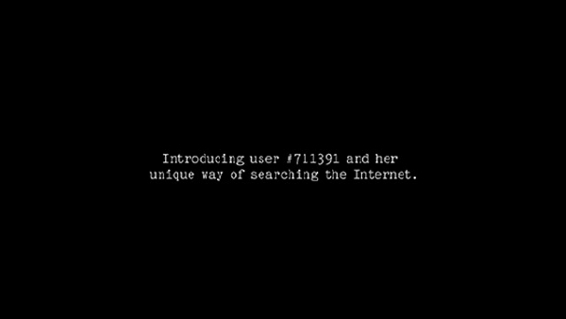

I Love Alaska is a fifty-minute-long online mini-movie divided into thirteen episodes and was made by Dutch artists Sander Plug and Lernert Engelberts. The movie draws on the residue of an event in media history: when AOL leaked over 650,000 users’ search histories from a three-month period, which was intended to be made available for academic researchers but was accidentally leaked publicly online for three days in August 2006. The filmmakers focus on one user’s search history: #711391, identified by a number sign. The movie features a woman’s voice narrating a selection of the user’s search keywords over images of Alaska —ironically evoking one strand of the search that eventually suggests the user is planning a family vacation to Alaska. The irony is all the more biting when juxtaposed with other components of the user’s search history, about marital infidelity, explicitly sexual curiosities, celebrity gossip, and anxieties about illness.

The first episode begins with a fast left-to-right swipe of white text across a black screen, accompanied by a machinic sound that signifies the presence of an advanced, efficient recording technology, that reads: “On August 4, 2006, AOL accidentally published a text file on its website containing three months’ worth of search keywords submitted by over 650,000 users.” After a few seconds, we then hear wind blowing, sonically bridging the image track’s transition to a shot of Alaska, where the frame of the image is adjusted and we hear the sound of a computerized surveillance system accompanying the adjustment, giving the viewer the feeling of approaching the film from the perspective of spies, zeroing in on our target. After we settle on an image of a snowy mountain, the film presents us with another textual swipe: “The keywords in this file were typed into AOL’s search engine by users who never suspected that their private queries would be revealed to the public.” We return to our positions as voyeurs, looking at a snowy landscape, and the film plays with the image’s brightness. Another textual swipe: “After three days, AOL pulled the file from public access, but not before it had been copied widely on the Internet.” Another image adjustment of a scene in Alaska, and then we see: “This movie presents the true and heartbreaking search history of user #711391.” The title credits then come on the screen; we are informed that this is Episode 1, dated March 1-7, 2006, and a final textual swipe reads: “Introducing user #711391 and her unique way of searching the Internet.” We then cut to what looks like a curtain being lifted from a window, accompanied by an exaggerated sound effect of the curtain being lifted, revealing a scenic view of Alaska, with mountains in the background and pine trees surrounding tiny buildings in the foreground. We hear a bell ding, white text in the lower left of the frame reveals that this is Wednesday, March 1, 2006, and over the still image we hear a woman’s voice: “Cannot sleep with snoring husband.” A few seconds later, “How to sleep with snoring husband.” We hear a dog barking in the background. “How to kill mockingbirds.” “How to kill annoying birds in your yards.” We hear a bird sound. “Online friendships can be very special.” Another ding, and then we move on to the next day’s searches.

Some other queries eventually revealed include the following:

“adults with nervous tic,”

“gay churches in houston tx,”

“pimple that gets white head on it and never goes away,”

“how many online romances lead to sex in person,”

“things for kids to do in alaska,”

“how can you tell if he used you for sex,”

“christian women caught in extramarital affairs,”

“poems about friendship,”

“adults with nervous tic,”

“how does a person get over internet addiction,” and

“nicole richie is a bitch.”

The filmmakers’ project raises ethical questions that, in light of subsequent events — from WikiLeaks’ unveiling the contents of diplomatic cables in 2010 to Eric Snowden’s release of documents revealing the National Security Agency’s massive surveillance programs in 2013 — are increasingly pertinent in culture today about access to information, privacy, security, and the Internet. When the AOL leak occurred, many researchers felt that using the leaked information violated their ethical commitments. Jon Kleinberg, a computer scientist at Cornell, stated in response to the leak, “The number of things it reveals about individual people seems too much. In general, you don’t want to do research on tainted data.”20 Christopher Manning, a computer scientist and linguist at Stanford, felt that the possible advantages to using the information for research outweighed the ethical stance that it should not be treated as a valid data set. Despite acknowledging “genuine privacy concerns,” he believed that “having the AOL data available is a great boon for research.”21 Through its own artistic entry point to and reliance on this leaked data, I Love Alaska provocatively refracts this ethical conundrum, obliging its spectator to consider the extent to which the filmmakers themselves are complicit with AOL’s breach of privacy and engage in an ethically inappropriate act. An unavoidable question that I Love Alaska raises, in other words, is whether it is an ethically sound documentary project. Without any metacommentary, is it able to pass as a critique of AOL? Do the filmmakers violate the user’s right to privacy and intimacy by drawing attention to her search history? Or, viewed from a more redemptive perspective, could I Love Alaska be interpreted to function as a critique of the very ideology of privacy — that our data belongs to us?

Twitter and the AOL search leak temporally coevolved: Twitter launched in July 2006, AOL’s search leak occurred one month later in August, Chris Messina introduced the # sign on Twitter in 2007, and I Love Alaska was completed by 2009. The two phenomena, I would argue, are part and parcel of a broader cultural “hash logic” of searchability and distributability, of hoping that the answers to our questions can be both archived and provided by outsourcing our uncertainties to networked computing machines. I Love Alaska’s textual dynamics seemingly strictly adhere to data and, by extension, legitimate its truth claims. Significantly, the movie’s protagonist is identified as “#711391.” This identification by number sign speaks to the film’s larger relationship to fact, giving the impression that the filmmakers are simply relaying content from a database, without veering into subjective interpretation. Along with the numbers provided by the movie’s reliance on episodic divisions by weeks and individual sequences by date, the number sign evokes a sense of mathematical precision and historical accuracy; semiotically speaking, it carries what Roland Barthes might have called the “dream of scientificity.”22 The character indicates also semianonymity: it is a precise identification number belonging to and serving to identify only one person as a highly specific data-collecting and -generating body yet at the same time renders the person unnamed, faceless, and dehumanized.

In this sense, I Love Alaska is suggestive of the # sign’s allegorical potential for describing the condition of digital culture: as part of a system for organizing, communicating, and differentiating what Helen Nissenbaum refers to as our “personal information flow” in an increasingly networked and information-based society.23 From this perspective, the sign’s function is in fact quite continuous with the hashmark and the telephone’s number sign: an iteration for managing information, organizing data. To recall the discussion of the Human Rights Campaign’s equal sign in the introduction, on AOL — like so many other contemporary services — we are data bodies, encoded in and represented by mathematical symbols. We are, in short, the digital’s digits.

By presenting information contained in leaked search histories, and without relying on extracontextual content, I Love Alaska plays with our desire to infer narrative from data. In the first day alone, we encounter an exposition that hints at the protagonist’s dissatisfaction with domestic life — bothered by her husband’s snoring and birds in the backyard — and curiosity about a virtual life beyond her home that her computer connects her to, with either the possibility of or an already forming “online friendship.” As the days proceed, the viewer infers from the data presented a narrative featuring a character we might imagine to be a married, middle-aged, neurotic Christian woman living in Texas who has fantasies of extramarital and alternative forms of sex, and, in the three-month span of the movie’s plot, has an affair with someone she meets online and regrets it.

It is instructive to contrast the movie’s staging of the desire for narrative and character with a New York Times cover story that gives in to it, tracking down a violated woman behind one of AOL’s user numbers. Within a few days of the information leak, the newspaper published a piece on its front page titled “A Face Is Exposed for AOL Searcher No. 4417749.” It was accompanied by a photograph, also on the front page, of Thelma Arnold, an older woman with a small black dog standing on her lap and kissing her face, with a caption reading: “Thelma Arnold’s identity was betrayed by AOL records for her Web searches, like ones for her dog, Dudley, who clearly has a problem.”24This caption’s joke is a reference to one of Arnold’s searches identified in the article for “dog that urinates on everything.” This front-page story serves as a counterpoint to Alaska, providing the absent “face” behind the semianonymous user number. Even though the New York Times piece in a sense reveals more — the name and private searches of the user as well —within Helen Nissenbaum’s framework of “contextual integrity” for discussing privacy and digital media, it would likely be viewed to be more ethically sound, largely because the piece interviews Arnold and we can therefore presume that she has willingly consented to the information’s publication.25 I Love Alaska, on the other hand, offers no such consolation: the woman remains unnamed, and there is no evidence suggesting the user approves of the artistic appropriation of her personal information flow, particularly given its dark, private, and likely embarrassing nature.

A second way to frame the distinction between these two texts is in narrative terms: the New York Times story not only offers a character’s name and face, but it offers one of the most attractive and necessary features that narrative has to offer: closure. A woman’s personal information was wrongly revealed, AOL fixed their mistake, she was identified, she spoke to reporters, and now readers see her dog happily kissing her. By contrast, the movie is steadfastly resistant to cleaning up the messes of digital culture. It confronts its viewers with them — and with a pessimistic paradox. On one hand it stands as a reminder of the public’s weak historical memory that new media and its outlets are in the business of making us forget (who recounts or even recalls this search leak anymore?), but at the same time that the event is impossible to remember, it is also impossible to forget. In recirculating leaked data, I Love Alaska is suggestive of the historical event’s impossibility to achieve closure, drawing on the inevitable residual consequences of the AOL leak: though the company removed users’ search histories from the Web, that did not stop others, during the three days when the information was publicly available, from downloading and storing the information elsewhere. Years later, #711391’s data, along with many other users’ search histories, can still be easily accessed.

Figure 26. I Love Alaska (directed by Sander Plug and Lernert Engelberts, 2009)

I Love Alaska could be understood to stage what media theorist Lev Manovich describes as the crucial antagonism between narrative and database, which he claims new media in general throw into relief. He observes that with literature and cinema, “the database of choices from which narrative is constructed (the paradigm) is implicit; while the actual narrative (the syntagm) is explicit. New media reverses this relationship. Database (the paradigm) is given material existence while narrative (the syntagm) is de-materialised. Paradigm is privileged, syntagm is downplayed. Paradigm is real, syntagm is virtual.”26

What I thus want to suggest is how this movie, digital through and through — from its subject matter to its critique, from its mode of production to its mode of distribution — might be impossible to fully understand outside of what this chapter has been considering as hash logic. Hash logic is in other words a logic of keywords, searchability, and informaticization; it strips down language to basic elements, to bits of information. From this data, the reader or Internet user is set on a task of inference and filling in gaps, or as Manovich would say, of deducing syntagm from paradigm. A text such as I Love Alaska, whose language is reduced to only keywords, precisely through its textual restraint, demonstrates how narrative desire is structurally fetishized by this logic.

At the same time, this movie stages the problematic status of indexicality in the digital age, whereby our access to reality relies less on the presumed authority of the photographic image and increasingly on a presumed authority of the algorithms used to access information. Its content, composed of search terms, not only points to our investment in the belief of a universal index, but, presented in a moving image medium, it also reminds us of indexicality’s other side. The identification number points indexically, after all, to a person with thoughts and intentions who exists in the real world. The proof of this reality, however, is not photographic or visual. Indeed, the images of Alaska that the film provides adamantly insist that we are operating outside the logics of visual indexicality. We have no proof that user #711391 ever made it to Alaska with her family. Maybe in the end her extramarital affair destroyed her marriage, or maybe a family vacation to Alaska was just another fantasy she was addicted to imagining, an escape from Texas’s stifling heat. Or, maybe user #711391 does not even correspond to a single person, as the movie’s narration slyly wants us to believe. In reality, there is a fair possibility that multiple members of the household were sharing one account — hence the range of sexual fantasies explored and also the paranoia not only about cheating but about accessing Internet search histories as well (one query reads, for example, “how can you tell if a spouse has spyware on your computer”). Even if #711391 is a she, and even if she did make it to Alaska, we can rest assured that the film’s own images of Alaska do not belong to her.

Without a face behind the user, we are, it would seem, only left with fingertips, if here they are implicit. As a return to Vilém Flusser’s poetics, one might sense a series of fingers playing with computers: whether it is AOL user #711391 exploring a new intimacy with her computer or whether it is the filmmakers, ultimately editors, using their fingers manipulatively, to match images with sounds that have no inherent, indexical connection. The false indexicality of the image, in other words, is exposed, while we are confronted with an index of what would seem to be of an altogether different nature. The index as digit as number sign. All conflated by a sort of hash logic into Jimmy Fallon’s late night finger-pounding shenanigans.

Emmanuel Levinas’s well-known reflections on the face in Totality and Infinity are instructive to remember in this context. In a key passage, he writes, “[T]he face speaks to me and thereby invites me to a relation incommensurate with a power exercised, be it enjoyment or knowledge.” Levinas suggestively posits the face as a rubric for ethical engagement, using the extreme case of murder as an example: “The epiphany of the face brings forth the possibility of gauging the infinity of the temptation to murder, not only as a temptation to total destruction, but also as the purely ethical impossibility of this temptation and attempt.”27 Another way to make sense of Levinas’s point would be to understand the claim as follows: it is when we are face to face with the Other (to hold on to Levinas’s terminology) that we are in effect able to determine what our ethical relation to the Other is. In the absence of this face, our ethical compass is tumultuous and less grounded; we are not reminded of the human being for whom our decisions have consequence. This notion hinges on the assumption, as so many writers have claimed in various contexts — to take an example from classical film theory, one might recall Béla Bálazs’s writings on the close-up — that the face is an expressive landscape upon which one can read the range of human emotions.28 Extended into the 2010s, this phenomenon of course surely contributes to Facebook’s enormous success as a social networking site: a virtual sea of profile pictures of faces connected to each other, communicating, and sharing information. Levinas’s point also, I would contend, accounts for I Love Alaska’s ethical ambiguity: without a face behind the user and only her number, a viewer has difficulty assessing his or her ethical engagement with the text.

In a sense, we return full circle to where this book began: staring into the strange everydayness of the Facebook profile picture, and with a new reading of the equality sign phenomenon. Perhaps it is the massive facelessness this event staged that confronts us with an ethical ambiguity similar to what we find in I Love Alaska. Many users of the site believed that uploading an image of an equal sign in the place where they normally show their face was the “right” thing to do, to show their support for marriage equality. But when datasets or typographical characters replace human faces, the effect throws us out of the regime of right and wrong or good and bad —and into a loop of floating signification.