University Startups and Spin-Offs: Guide for Entrepreneurs in Academia (2015)

Part I. Strategies for University Startup Entrepreneurs

Chapter 10. Communication Skills and Meetings

Talking about their project with outsiders is an important skill that entrepreneurs often overlook. How difficult can it be to present something to a visitor? Presentation skills are often taken for granted, but in reality, good communication is the lifeblood of entrepreneurship. Because startups rarely take off in isolation, it is worth spending some time mastering communication skills. Students and researchers may find tactics related to communication too salesy or otherwise unfit for academics. Overcoming that hurdle is one of the points of this book: leave the ivory tower, and get feedback from the real market. The sooner university entrepreneurs warm up to this concept, the better.

PowerPoint

Researchers are used to presenting their findings to other academics, so they naturally assume that they already know how to give talks to third parties. What they fail to consider is that non-academics are used to a different presentation style and format than academics. A startup entrepreneur should avoid addressing potential partners and investors as if they were faculty. I have sat through hour-long presentations of 200 mostly unreadable PowerPoint slides, most of which the presenter skipped with the remark “I don’t have enough time to show this here.” Many of the slides were brimming with justified 12-point type, intricate diagrams, and tables of even smaller type. In addition to being utterly boring, such feature-laden demonstrations lack any actionable steps to engage the audience. Presenters simply beam data down to the listener, and when the time or the information runs out, they stop. This may be OK when you are presenting to a specialist who has an interest in such detail, or anyone unfamiliar with a better presentation style. However, when pitching a potential joint venture partner or investor, such a practice may reflect badly on you. It shows that you are going through the motions with little understanding of how the business and investing world works.

To be fair, it is not only individuals from universities who lack presentation skills. Most presentations given by startups and multinational corporations are rather dismal. There is a lot room for improvement in all domains. Effective communication is never a one-way street. It is not just a question of telling but also of listening. Entrepreneurs are hardly the only people who must learn this.

So how can a startup make its presentations more palatable? Let’s establish a few ground rules and technical parameters that make it much easier to tailor your presentations to diverse audiences and applications.

The 10/20/30 Rule

A framework often used in Silicon Valley is the 10/20/30 rule put forward by author Guy Kawasaki: 10 slides, 20 minutes, minimum font size of 30 points.1 This technique is daunting for most people on first sight. However, it works. You must fit all the essential information on ten slides, excluding the title slide. What information, you ask? Most third parties want to see the following points:

1. Problem

2. Your solution

3. Sales and business model

4. Technology

5. Marketing and sales

6. Competition

7. Team

8. Projections and milestones

9. Status and timeline

10.Short summary and call to action (next steps)

When you pitch to a joint venture partner, you may adjust some of the slides. Instead of a sales and business model, at point 3, you may put the partnership model that you imagine. You may omit point 5, marketing and sales, and replace it with distribution channels. 10/20/30 is open and malleable, as long as you follow the iron rule of a maximum of 10 slides with a minimum font size of 30.

The most important slide is number 10: the call to action. Only with this last step will you engage your audience. Never leave your audience with the task of coming up with the next steps to take. If lunchtime is five minutes away, they will rarely spend much effort on this. As an entrepreneur, you need to do the thinking for other people and tell them what you want them to do for you. This is also where your one-page proposal fits, as an extension of this final slide.

The large font size is paramount for several reasons. First, when you present with a projector, the contrast in the room may be weak, and small fonts will be unreadable. You could darken the room, but then people will fall asleep. It is best to avoid this problem by using at least a 30-point font size. Second, when you print a presentation and show it on paper, the people you are presenting to may have bad eyesight. Most of them will skip unreadable tiny print and will politely nod, so you will never know that most of the information went over their head. And finally, because a large font acutely limits the space available per slide, it forces you to condense. Cut out anything that is unnecessary. Producing a lot of text is easy; the magic lies in making your presentation concise. People have gotten used to reading 140-character Twitter messages that include a lot of information, so you will be at an advantage if you master the skill of keeping it short. (By the way: the same goes for e-mails and any other written documents. The shorter, the better.) You can still make a long version and include links to your in-depth publications, should anyone ask for them. Most people have little time and just want to find out the overall gist of your project.

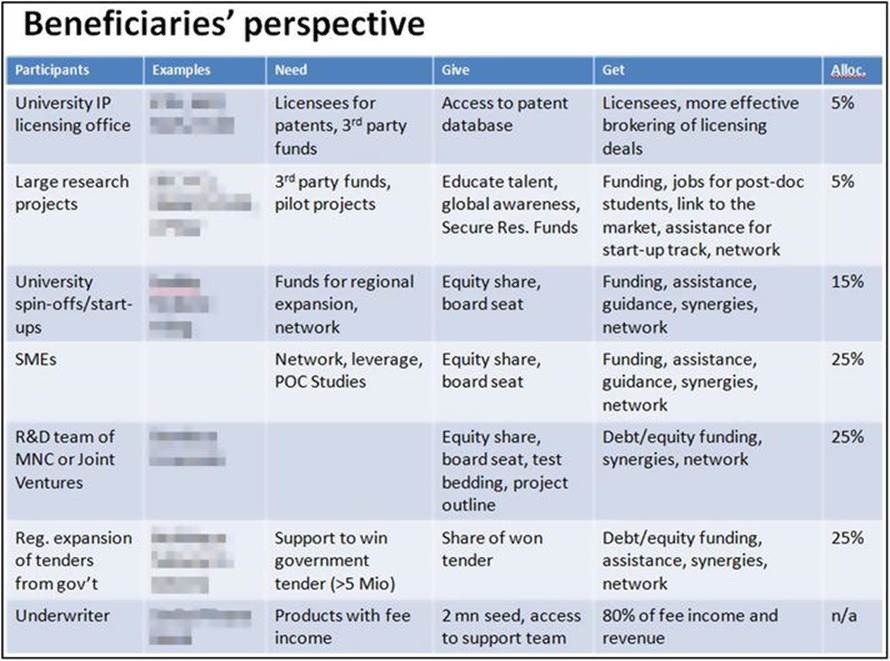

What about tables, which need to use a much smaller font size to fit on the slide? What does not fit has to go. Simply omit anything that is incompatible with the 10/20/30 framework. You can always convey the same information with fewer words. Figure 10-1 is an example from an actual project I was working on: this is the original slide with some names obscured. It contains information about the benefits of a certain platform for patent-licensing offices. The 15-point font is difficult to read, especially from a distance. The colored table format provided by PowerPoint looks good in print, but the contrast is too weak for an overhead presentation. The audience starts reading at top left, makes their way down to the second line, and then gives up. You may be talking or explaining what you mean to say with this table, but the slide and your words will be incongruent. As you may have guessed, this slide is unpresentable.

Figure 10-1. PowerPoint slide before applying 10/20/30

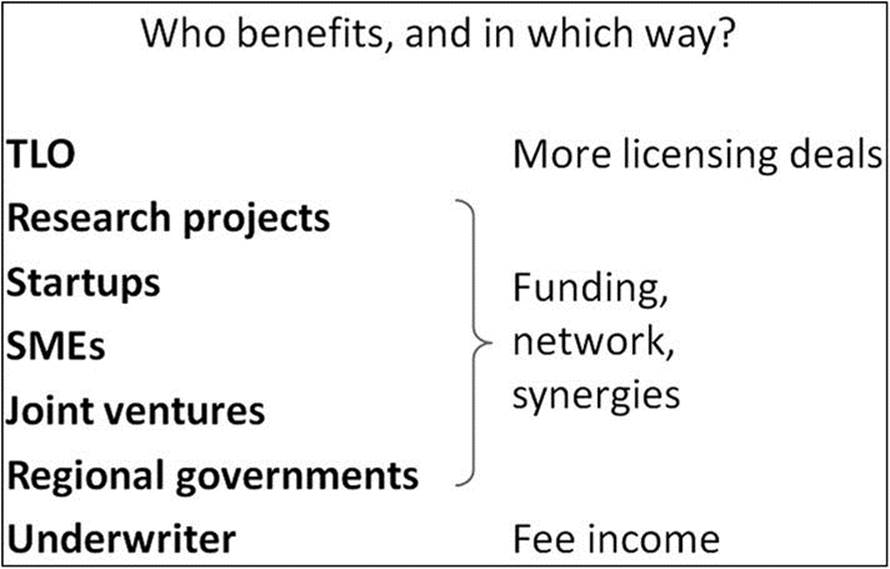

Figure 10-2 shows how to improve this slide. Even though it contains more or less the same information, this version looks clean and makes sense at a glance. There is no fancy formatting: just clear information. On the left you see the beneficiaries, and on the right, the benefits. The columns for the motivation and contribution of each party are unnecessary to drive home the point that the platform has value, so you eliminate them.

Omit all information that confuses the story or makes it difficult to understand. If anyone has specific questions, they can ask after your presentation, which only lasts 20 minutes. This leaves the audience with enough energy to follow up if something is important. If the missing details are key for the overall story, you can print the table and make it available to those who wish to know more.

Assume you are in a day-long workshop to hammer out the terms of a potential project. Each speaker has one hour to make a presentation. Instead of fretting about how to fit your 200 slides into 60 minutes, stick to the 10/20/30 rule. Speak for 20 minutes, and then get feedback from the other attendees. What exactly is their problem? How have they addressed it in the past? Has this worked for them? Why or why not? What happens if they keep doing what they have been doing? How could your solution better solve their problem? Use the SPIN technique described in Chapter 5 to link the benefits you can bring to the table to the needs of the other parties. Your presentation becomes a platform for discussion, and you engage others in your project.

Figure 10-2. PowerPoint slide after applying 10/20/30

Communication about your startup goes far beyond PowerPoint. It is a skill and a mindset that applies to all your interactions with others. Once you have internalized a few ground rules, you can apply them to various situations.

Have a Backup Plan Ready

It goes without saying that if you need to hook your computer to a projector, you should do this before the presentation to make sure everything works. If the projector fails to link up with your laptop, have the presentation available on a USB stick and use another machine. As a last resort, bring a printout of the presentation that you can photocopy if all else fails. When the presentation begins, you should have checked that everything works and should have taken all possible steps to make it work. Blaming the technology or the technician and shrugging your shoulders will only reflect badly on you, so do not go there. It is your full responsibility to make your presentation work.

Elevator Pitch and Micro-Scripts

It can always happen that you meet someone in the proverbial elevator, and they ask you what you are currently working on. As a startup entrepreneur, be ready to pitch your project at all times. Who knows? Perhaps the other person can help you with something, or works on a similar project, or can introduce you to an influential contact. This is when your elevator pitch comes in handy. It is a highly condensed synopsis of what your startup is about and why it matters. This pitch should come across naturally without sounding rehearsed. Keep it simple, and focus on the most prominent points of your venture.

The following practice to craft your elevator pitch comes from advertising. Yes, you heard right: you are creating an advertising slogan for your university startup. Before you decide that this is too cheesy and un-scientific, remind yourself that you are not publishing your elevator pitch inNature. It is just a brief summary of the benefits your startup delivers to a client. Businesspeople are used to such pitches, and when you apply them intelligently, they work great in academia.

Micro-script rules, developed by author Bill Schley, are excellent building blocks for elevator pitches.2 “It’s not what other people hear, it’s what they want to repeat,” as he puts it. The following set of simple rules helps create a short, memorable message that drives home the main point about what you want to communicate. In creating your micro-script, stick to the following guidelines:

1. One attribute.

2. The narrower your focus, the wider the message goes.

3. Simple always wins. The average length of successful scripts is less than six words.

4. Be specific.

There are further rules, but these are the ones I find most workable.

Now you have a recipe to cook up your elevator pitch. Let’s see how this works with an example. For this, we go back to the battery startup from Chapter 2. What is their product’s one quality? Potential candidates are “rechargeable in ten minutes” and “biodegradable.” Because “rechargeable” did not make the cut in MVP testing, this is easy: we focus on “biodegradable.” The narrow focus means the startup’s first product is a car battery, as they found out in MVP testing. Specificity means the battery is not just “good for the environment”: it is so many times better, or it saves so many lives or so much soil or water from contamination. For illustration purposes, some possible micro-scripts for the battery startup are as follows:

“The biodegradable car battery that reduces water pollution from heavy metals by 50%.”

“Each car battery helps protect one acre of farmland from heavy metal pollution.”

“The car battery that dissolves to compost.”

It is helpful to avoid touting the features of your technology, but rather the benefits. A feature would be the chemical composition of the battery acid. It’s better to speak about the benefit of biodegradability, which listeners can then repeat to other people after they hear the micro-script.

This is just an example to show that you need to be creative with your micro-scripts. Write down several of them, and test which ones work best. These short sentences can be the building blocks of your elevator pitch.

So how do you use your elevator pitch? Let’s find out with a fictitious example. Assume the following situation: Ben and Christine from the battery startup are waiting at a taxi stand. In line right behind them, Ben notices the CEO of Big Battery Corporation (BBC) waiting for a cab. Ben recognizes the CEO from a news article he saved—he wanted to write a letter to BBC about a potential joint venture. The taxi line is barely moving, and Ben figures he has three minutes to speak with the CEO. He seizes the opportunity and introduces himself.

Ben: “Hi, Mr. CEO. I recognized you from the article in The Business Post last month. My name is Ben, and this is Christine. We just founded a battery company. Here is my card.”

CEO: “OK …”

Ben: “We are working on a biodegradable car battery that can reduce water pollution from heavy metals by 50%. We’re testing the battery now in the market with very good results.’

CEO: “Hm.”

Ben: “Yes. I planned to write to your R&D department and introduce our company. We are currently looking for a joint venture partner to raise some funding. We are actually raising $250,000 right now, which should be enough for the next six months to refine the technology, and I would like to ask your company if …”

CEO: (Interrupting Ben) “Listen, it’s 10 p.m., and I had a busy day. We already work on similar technology and have no headroom for another joint venture.”

Ben: “Oh, really!?” (Long pause.) “Uhm, OK. Well, good luck with the technology you are working on …”

Did this go well? Not at all. But that happens when you forget to rehearse your elevator pitch and are unclear about what you want from the other party as the actionable next step. Even though Ben started out fine with his micro-script, the rest of his elevator pitch was much too straightforward. Begging others for money is the last thing that should come across in your elevator pitch. Instead, focus on what you can do for the other party. Move the conversation just one step forward by breaking down your goals into smaller steps. If you move ahead steadily in interactions with others, you will reach the goal faster than if you try for a home run every time. Let’s rewind and see how the situation could have played out better:

Ben: “Hi, Mr. CEO. I recognized you from the article in the The Business Post last month. My name is Ben, and this is Christine. We just founded a battery company. Here is my card.”

CEO: “OK …”

Ben: “We are working on a biodegradable car battery that can reduce water pollution from heavy metals by 50%. We’re testing the battery now in the market with very good results.”

CEO: “Hm.”

Ben: “Yes. I planned to write to your R&D department and introduce our technology. It could be in line with your new sustainable product line Z. Would it be possible for us to make a presentation?”

CEO: “Listen, it’s 10 p.m., and I had a busy day. Why don’t you call the office and set something up with R&D?”

Ben: “Great, I will do that. Oh, here’s a cab. Why don’t you go ahead of us? Have a safe drive home, and we’ll be in touch tomorrow.”

Was this interaction successful? I think so. Even though the CEO was still grumpy, Ben got to the next base. He of course still has a long way to go to secure funding and a joint venture, but he is one step closer to a potential partner. The CEO has no reason to reject him. Ben can contact BBC tomorrow and refer to the CEO’s recommendation to call the office. He may even send a greeting card to the CEO and thank him for his time and his suggestion to call. Thereby he has set up a link to a potential partner that may be of much value to both of them down the road.

Prepare and Rehearse Your Pitch

Your message has to be clear and refined, and this never comes overnight. Most important, whenever you give your elevator pitch to someone, do not ramble. This is a sure deal-breaker. Keep it simple and short, and use memorable phrases like your micro-scripts. Make sure you give the other person enough space to breathe, and take breaks between your sentences. To deliver your messages with perfection, make sure you have rehearsed them properly. It is more difficult than you think to bring across your information confidently and still make it sound unrehearsed. This needs practice. But it is well worth doing and will go a long way.

Get your team together, and start pitching to each other. See which micro-scripts work well by testing them frequently in casual conversations. Practice does not always have to be in front of the mirror. Get in the habit of obtaining feedback about your ideas everywhere you go. Over time, this prepares you to get it right and make it sound natural at the same time.

Unless you practice your elevator pitch, the right words will elude you under stress. As the example of Ben and the CEO shows, always think in terms of next steps. If you can advance the dialogue, it is successful. Interactions that linger in indecision are unsuccessful and a huge time waster. If you fail to pay attention, you may not notice this is the case, with actionable steps postponed from one meeting to the next. When you are setting up a meeting, clearly think about what you want from it.

What Is the Actionable Next Step?

Being too straightforward right away is a turnoff. The first contact should just be about getting to next base, in this case a formal meeting to present your technology. It could also be MVP testing with a company already active in the marketplace. Or general feedback about your approach and your assumed target market. When you meet a person in the elevator, refrain from pushing your entire PowerPoint pitch deck on them. The actionable next step is to organize a meeting where you and your team present the entire pitch. Whatever it is you want, be clear to approach it in small steps.

With the SPIN questions (situation, problem, implication, need-payoff), it is much easier to frame the discussion around the benefits of your products instead of their features. Going into the meeting to “just get to know” the other party is not enough and will rarely move the interaction forward. With this, you are depriving yourself and the other party of potential value that could come out of a potential collaboration down the road.

Note how all the techniques and the work done on your startup so far build on each other. With MVP testing and the business model canvas, you found your unique value propositions, which you highlight in your elevator pitch. With your financial model, you can lead an informed discussion about pricing and your needs when it comes to forming a joint venture or raising investment. And the right communication skills tie it all together. Without them, nothing else would matter because you would be unable to bring it across when you meet a decision maker. The strategies outlined in this book are straightforward and may even seem simplistic at times. However, putting them all together, you will end up with a workable approach to entrepreneurship that has been successful for many startups. Only when you have a clear picture of your startup can you express the exact next steps you want others to take on your behalf.

Take Control of Unexpected Situations

Have you ever given an interview to the news media? They are usually very short, sometimes just 30 seconds. The interviewer asks a generic question, and you answer the best you can until the next question rolls around or the interview is over. Most people are in a reactive mode during an interview, and this is not how an entrepreneur should use this opportunity. Instead of nicely answering the interviewer’s questions, have your pitch ready, and be prepared with the story that you want the world to know.

Let’s see how this works with another fictitious example. Assume there was a volcanic eruption in Indonesia yesterday, and a news team is now filming an interview at your university. As the team lead on the volcanic-eruption module, you are slated for the interview. Let’s see how this unfolds:

Interviewer: “As a leading expert in volcanic-eruption modeling, what is your prediction for future volcanic activity in Indonesia?”

If you are like most people, you will respond the best you can to the question about volcanic activity in Indonesia. After all, that’s what the interviewer wanted to know, right? Perhaps you say that no models could predict what happened and that we do not know when the next eruption will be. Or perhaps you speak about the history of eruptions and note that this one was actually long overdue. You play nice with the interviewer and tell her what she needs for her news bite. She will politely thank you and move on to the next news item. This is how most such interviews progress.

Assume, however, that in addition to being a leading expert on volcanic activity in Indonesia, you are also a startup entrepreneur. The startup you incorporated two days ago, let’s call it Seismic Software, already has a tentative joint venture pact with a multinational sensor company, SensorX.You have worked on a model that has in lab tests outperformed other models. You feel it has a wide variety of applications not only in eruption modeling but also for earthquakes, tsunamis, terrestrial explosions, and so on. By chance, you find yourself standing in front of a camera for the national news media, and a reporter asks you about the volcano in Indonesia. What do you do? You can play along with the interviewer and give the generic answer that 99% of all other researchers would give because they are excited to be on TV. Or you can hijack this opportunity and take matters into your own hands:

Interviewer: “As a leading expert in volcanic-eruption modeling, what is your prediction for future volcanic activity in Indonesia?”

You: “Thanks for asking me this question. This latest activity in Indonesia has been largely a surprise, which is mainly because most models date back ten years. My team and I at Seismic Software are working on an advanced model that holds much promise. We predict not only eruptions like the one we have just seen, but also earthquakes and tsunamis up to ten minutes earlier than current systems in use. We’re currently testing our model in Japan with SensorX, our joint venture partner. The first tests are promising, and it will be exciting to see how we can improve prediction in the future. In fact, this short simulation video shows how we predict future eruptions with our software.” (Shows 20-second video clip on a laptop.) “You see here how we get a clear signal of seismic activity about ten minutes before the felt impact on land. This is mainly thanks to the way our software communicates with the SensorX sensors. In this video, you see our team from Seismic Software at a test site in Indonesia.” (Shows other 20-second video clip.) And so on, and so forth.

What just happened? The interview is now about your company and your product and not about Indonesia. If the interviewer has time for another question, she will most likely follow up on your model, your tests, or your company. Or she may want to show your videos with the credit of your company in the news bit. Do not worry about talking too long—the news team can always edit your interview. The elevator pitch should be short, that’s true. But that applies when you pitch under time constraints. When you have the chance to tell your story to the world on the news, you should have a lot of interesting material to talk about. In the example, you made a powerful pitch that put your own company and also your joint venture partner in the spotlight on the national news. Make sure to exchange business cards with the film crew and anyone else on the set. You could double up and invite the news crew to your lab to film a special report about prediction software.

You never know what these encounters may lead to. The most important thing to remember is that entrepreneurs first and foremost have the benefit of their own company in mind. When there is a chance to get a platform, make the platform your own. You could not possibly buy the visibility you get from these opportunities.

A Word about NDAs and Confidentiality

Attorneys advise you to have third parties sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) when you show those parties confidential information about a technology and want to discourage them from copying or stealing your invention. If you have a patent (pending), then your invention is somewhat protected from plagiarism, but you still have to enforce against potential infringement. This can be time-consuming and expensive. An NDA should, in theory, protect you from intellectual property theft. The reality is that NDAs are impractical. Better than relying on NDAs and patent protection is keeping the crucial parts of your invention under wraps. My experience has shown that an NDA often frames a discussion in a negative light, because it presupposes the other party will naturally steal your intellectual property. Many venture capitalists will tell you straight out that they never sign NDAs. If you insist, the meeting is over.

A better strategy than an NDA is incremental disclosure. First, by focusing mostly on the benefits of your technology and not the features, you avoid revealing the secrets behind your invention. In the example of the battery startup, they should avoid disclosing their product’s chemical composition in the first meeting. But they should highlight all the benefits it brings: biodegradable up to X%, contains no heavy metals, protects water and soil, and so forth. When the potential joint venture partner asks sensitive questions, you sidestep with the answer that you can discuss those in a later meeting. If your invention is obvious—for example, if one glimpse at the battery immediately tells the other party about the technology behind it—then leave it in your top secret lab. Bring a mock-up or a diagram with the sensitive parts obscured. The more the relationship progresses, the more you show. When you have signed a joint venture agreement, then all the intellectual property is shared, and there are no more secrets. Only when you think in terms of features, not benefits, will you be afraid of intellectual property theft.

What Should You Bring to a Meeting?

Let’s say you have a first presentation with a potential joint venture partner. How do you approach it? Let’s revisit the collateral you have produced so far and see how they are put to good use. This is what you should bring to a meeting:

1. Short summary for the meeting, with points to discuss

2. PowerPoint presentation on a laptop or printed

3. Business model canvas

4. Financial model

5. One-page proposal, if you have something to propose

6. Additional materials

Let’s look at each item in more detail.

Points to Discuss

When you go to a meeting, make sure you are coming from a position of preparedness and strength, not from a stance of begging for sponsorship or capital. The grant track focuses startups exclusively on securing funding from day one, but capital is hardly the most important asset others can provide. When you approach others, their experience and the synergies they bring are the most valuable assets for your startup.

Make it a point to lead the meeting with confidence. As an entrepreneur, you want to come across as goal-oriented and determined. When you communicate this way and the other party reacts strangely or withdraws, then you may have found out that they are not up to speed to work with you. Be glad you recognized this early. Use the meeting to show your worth and to test the other party regarding their ability and commitment.

Business Model Canvas or Lean Canvas

Whichever canvas you choose (I recommend the lean canvas), you should tailor it to the other party in each presentation. Parts of the canvas will flow into your PowerPoint presentation: for example, the slides where you explain the problem, solution, business model, and so forth. You may bring several canvases to address specific situations, such as your joint venture partner’s market and also the global market. Because you open the meeting with the PowerPoint presentation, the canvases are just backups in case the discussion progresses beyond the most obvious points.

Financial Model

Even though a joint venture partner will value your company on their own terms, the financial model is important to show the assumptions under which you operate. Do you project $1 million in sales or $100 million? Does your product cost one dollar or one cent? What is the potential profit margin, and what are the effects of scale economies?

The underlying logic of your startup and the market are more important than the numbers in the model. They show others how you think and operate. Make sure you explain your assumptions concisely as well. Bring the financial model with the output printed on one page for easy discussion.

One-Page Proposal

This document condenses onto a single page the entire discussion about your proposal for a joint venture or other proposition: your status quo, what you can do for the other party, and what you want them to do for you. Of course, never break out a joint venture proposal at the first meeting, before you even know the other party and have an understanding about how you could work together. This proposal makes sense when you have met the other party several times and are ready to extend or receive an offer. You can also prepare several different proposals.

In any event, before you go into a meeting, know what you want out of it. In a first meeting, you should ask for a follow-up meeting to discuss other parts of the technology, or get feedback on an MVP, or look at the joint venture partner’s processes to learn something new.

Technical Drawings, Sketches, Photographs

You should bring anything to the meeting that makes the point of your product being valuable to the other party, unless it gives away your intellectual property. If you have photographs of people using the technology, or drawings, or certain statistics that make a point, then bring those printed on separate pages. You will rarely need to show everything; just have more material ready as a backup.

What Should You Leave After the Meeting?

Print out the ten-page PowerPoint presentation and leave it there, unless it contains confidential information. Do not leave the lean canvas, the financial model, or any of your technical drawings. If you have presented a one-page proposal, leave that also, because you want a reply in the next few days regarding the next steps. Other than that, avoid flooding the other party with paper. You should make a sharp impression with your presentation and leave them wanting more.

Business Cards

Do you need your own business cards? Well, of course. When you are out and about as an entrepreneur, avoid giving people the card from your university. Print your own business cards at a professional copy center. They should include the following information:

· Your name and degree: for example, Dr. X, MBA.

· Your title at the company: for example, CEO.

· The name of the company.

· The address of the university lab where your startup is hopefully based in the beginning.

· Your personal mobile phone number.

· Your personal e-mail address. Get your own dot-com domain for your startup at a web-hosting company like Godaddy.com. This costs about $15 per year and comes with free e-mail accounts. Setting up your page and e-mail address takes ten minutes. This looks infinitely better than a faculty e-mail or Gmail address.

Your title is important. First-time entrepreneurs are often unsure about their role in the company. Are they the founder, the chief executive officer (CEO), the chief scientist, or all of the above? Avoid using the title Founder. If you are the boss of your team, then use the title CEO, or Managing Director, or President. If you are working more in the background on technical issues, put CTO (chief technical officer) or CIO (chief information officer). Read about these abbreviations on Wikipedia, and choose the one that best fits what you are doing. Use only one title, even if you have several roles.

The Business Lunch

A business lunch is distinctly different from getting together with your friends and family at a restaurant. The focus is on business, not on lunch. Eating together and sharing food is a gesture of goodwill among humans today just as it was in ancient times. It is more informal and cordial to meet over pizza than in a conference room. The topics discussed during the lunch are also different from those in a meeting, but they are still based on the premise of benefits over features, asking instead of telling, and actionable next steps.

I discuss the business lunch in a little more detail than the other skills in this chapter. This is because it is easy to spot a beginner during a business lunch. A great number of entrepreneurs blunder their way through lunches and lose much previously gained respect as a result of their amateurish behavior. I have no intention to micromanage your business lunches; this discussion simply shows you the moving parts that come together in this meeting ritual that looks so simple on the surface.

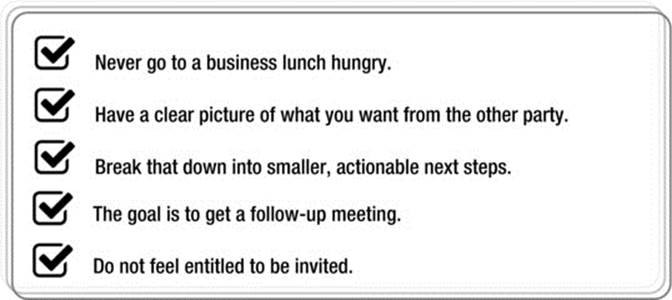

Let’s assume you had a brief meeting at a science summit with the CEO of a company that you may want to partner with later. You exchange cards, and he suggests that you get together for lunch sometime. You set up a meeting next week at a restaurant close to the CEO’s office. How do you make the most of this meeting (see Figure 10-3)?

Figure 10-3. Checklist for a business lunch

First, be sure you are early. Familiarize yourself with the place, and then wait for the other party to arrive. Do not arrive at the restaurant starving. Make sure you ate a good breakfast and perhaps a little snack just before lunch to avoid arriving at the restaurant undernourished, only thinking about food. Wolfing down your lunch seldom makes a good impression. In general, let the other party order first, and then order something similar. If it turns out the other person is a vegetarian, then refrain from ordering a bloody steak; order a small soup dish or salad. Always order a small plate so you have more time to address the issues you would like to discuss. Definitely avoid messy food, such as crab legs or anything similar, unless the other party orders the same and insists that you join them.

It is a good practice to stay away from alcohol at lunch, even if the other person orders a beer or glass of wine. You are not drinking buddies just yet. If it happens that the two of you become friends, then it is of course OK to go out drinking, but the first lunch meeting is hardly the time to drink together. Apply common sense. Make sure your lunch does not interfere with the business part of the meeting.

When it comes to paying the bill, the CEO will most likely invite you, but have enough cash on hand to cover your part. Offer to split the check. Be as persistent as you must, depending on your local customs. When you are invited, thank the other party for the lunch. However, never assume because somebody is richer or older than you that they must pay your bill. A sense of entitlement can be a deal breaker.

You need to have your business agenda planned in your head when you go to the lunch. Do not bring any paper, such as bound prints of PowerPoint presentations, unless the other person expressly asked you to bring them. Remember, you want to move each interaction to the next one. If the CEO wants to see more, then set up the next meeting where you will show your full presentation. Most first-time entrepreneurs make the mistake of wanting to hit a home run right out of the gate. That is hardly how relationship building works. Move step by step. The business lunch is a good opportunity to suss out the other party informally, get to know their opinion, and then present actionable next steps. What those are should be clear to you before you go to the lunch.

Let’s assume you want to ask the CEO if he can sponsor your product development with hardware. In a first meeting, such a commitment might be a stretch. What would the CEO get out of it: perhaps access to your other testing data, or insight you gained in developing prototypes? Present something of value before you ask for anything. Try to find out whether the CEO already has the data you collected. See if it would be helpful if you shared your findings. Ask him how his team approached a certain problem that you are struggling with. Offer the insight you gained from solving a similar problem. As the actionable next step, offer to show him some of your results directly at his company’s R&D lab. In that next meeting, you can begin inquiring about the possibility of potentially working together, perhaps by using their lab or some of their hardware.

Every meeting exists to lay the groundwork for the next one. Look at your meetings this way, and you will see them in a whole new light.

You Can Always Ask

As an entrepreneur, you must let go of your fear of asking other people to do things for you. Of course, I am not suggesting you bum out your friends with silly requests to buy dinner for you or let you crash on their couch for free with no end in sight. Those kinds of favors only go so far and end up alienating everyone around you. I mean well-researched requests that you may want to ask others to fulfill.

Let’s assume you want to meet the CEO of a company with which you would eventually like to form a joint venture. You have no personal connection to this CEO yet, nor does anyone in your network. At the same time, you think it would be good to get on the radar of her firm and hear her feedback about your MVP. What do you do? You should make contact with the CEO and ask her for a meeting to get her feedback about your early-stage product. Most people are open to giving their opinion about your work. They want to help others, especially if they can identify with them in one form or another. But remember that all relationships are give and take.

How do you contact somebody you have never met? Luckily, there is the Internet, which solves many of our problems. Most CEOs have an account on LinkedIn; make sure you connect there first. But a hurdle comes up: to connect with a person on LinkedIn, you often need to know their e-mail address or show that you have some other connection with them.

You can often guess e-mail addresses from the URL of a company. Most of them use the format first-name.last-name@company.com. Try that and see if it works. You can also say that you are a friend of the CEO. Sometimes you can choose a LinkedIn group that you are both a member of: join the same group as the CEO, and off you go. Try a few times, and see what happens. Eventually it will be possible to connect.

Why not simply send an e-mail to the company? E-mails from strangers fall by the wayside: most decision-makers receive hundreds of them each day. It is better to use alternative channels, if they are available.

Of course, you can also call the company and ask for a meeting. I recommend this only if you are well advanced on the path of MVP testing and can make the case for providing value to the company. Only go into a meeting if you are prepared and ready with actionable next steps for the other party. Never go “just to get to know them.” This will annoy the other party and make the next meeting more difficult to get when you need it.

With that in mind, you can meet anybody you desire in this world. Celebrities, billionaires, Nobel laureates—they are all just people in the end. If you appreciate their time and engage them in the right way with something they perceive to be of value, you will eventually prevail.

I once wanted to meet a famed investor to get his feedback on a project of mine in Asia. Because he ran several investment funds that had been active in Southeast Asia and China for over two decades, I was sure he would have some insight about these markets based on his experience. He often appears on CNBC and Bloomberg TV, speaks at various investment conferences, and is generally perceived as a jet setter, so chances were slim that this man would ever lend his time to me. So how did I approach this challenge?

First I sent an e-mail to his investment company in Hong Kong, not sure whether an executive assistant would screen them. For three weeks, I sent an e-mail each Tuesday morning with the request for a meeting in either of the two locations where he has homes. These e-mails went unanswered. So I switched to LinkedIn, as mentioned earlier. But there were several accounts with his name, some obviously fake. I connected with the two that looked real. To do that, I used the Classmate feature with my alma mater, for lack of a better alternative. Surprisingly, a few days later, both connection requests were approved. Once you connect on LinkedIn, you can see your new friend’s full profile and send them messages. That is what I did:

Dear X,

I would like to introduce myself in person to you. Would you be available for ten minutes this or next week by phone or in person? I am happy to meet you either in Y or in Z, at your leisure.

Notice that my first message contained no flattery about that person’s achievements. There was no word about admiring his work. Such statements put you in the position of a fan. Nobody wants to be friends with a fan. They only want to be friends with people on the same wavelength. There was also no time lost explaining who I was. That information was visible on my LinkedIn profile. Keep these introductory e-mails as short as you possibly can. Omit all fluff, and get right to the point. What did I want as the first action? I could have written that I wanted feedback about an idea, but this would have been an immediate turn-off. I just wanted to get face time. Afterward, I could bring forth my request for a follow-up meeting to present my project. You cannot force others to interact with you, but you can lead them gently with patience and persistence.

The answer I received was brief:

Sorry, I’m traveling.

At least there was a direct line now. What do you do when someone obviously has no time and no motivation to meet with you? Do you become a nuisance and pepper them with requests until they give in? They never will. You will brand yourself a spammer and will end up on their blocked list. Or do you put the ball in their court, sending your phone number and asking them to connect when they have time? You will never hear from them. Instead, be politely persistent, yet respectful of their time. You can always ask—but ask the right thing at the right time. This is a delicate skill that takes time to master.

It took two months until my first meeting with the investor came to pass. The first meeting took place in a “gentlemen’s bar.” I introduced myself and told the investor that I was an entrepreneur, and that some of my ventures had been in the Internet space. Before the meeting, I had prepared several suggestions for the investor’s personal blog, which could have used a makeover. I had also mapped out a strategy for a mobile app and a podcast that he might consider to reach a wider audience. All this I gave away without asking anything in return. This was about providing value to the other party and establishing the notion that this was not to be a one-sided interaction. I noticed that he relaxed slightly. He had probably expected an investment proposal, or a request for advice. Instead, most of this discussion circled around digital strategy and how he could use it to his advantage. This meeting was engaging and lasted several hours.

After that first meeting, it took another two months to set up the next. This time I asked for the investor’s opinion about an idea I had been working on. About five one-sentence e-mails later, mostly stating that he had no time or was abroad, the get-together was finally organized. Printed PowerPoint presentation in hand, I arrived at that same bar. Two hours later, all the bar girls had introduced themselves to me, but the investor had not shown himself. It dawned on me that this would most likely not happen today. When I returned to the hotel, I wrote a short e-mail asking whether everything was OK and whether a meeting in the next few days might be more convenient. The temptation to give up is strong in such a situation, and so is the danger of choosing the wrong words. Never write an e-mail when you’re angry or disappointed. Keeping it simple and to the point is the way to go.

Long story short, I eventually got what I wanted. The investor gave valuable feedback about the idea and even introduced a contact of his to help develop it further. This interaction was two-sided, and that is why it was productive. Few startup entrepreneurs I meet are thinking about first providing value to others. You can of course only provide value to others if you have something to say that cannot be read in a book. This is another reason to develop skills beyond your area of expertise: you never know when you or something else can use them.

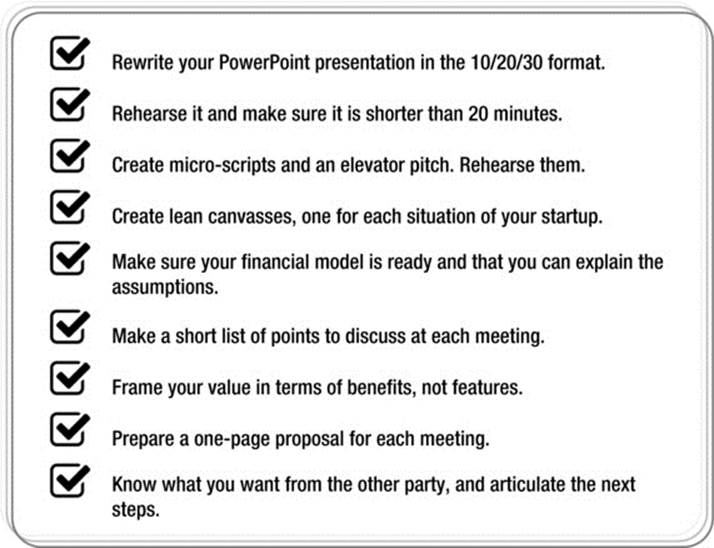

Figure 10-4 sums up the most important points about meetings and communication skills.

Figure 10-4. Checklist for communication skills

____________________

1Guy Kawasaki, The Art of the Start: The Time-Tested, Battle-Hardened Guide for Anyone Starting Anything (New York: Portfolio, 2004).

2Bill Schley, The Micro-Script Rules (New York: N. W. Widener, 2010).