University Startups and Spin-Offs: Guide for Entrepreneurs in Academia (2015)

APPENDIX A. Additional Considerations

The following articles and resources are related to startup entrepreneurship but go beyond the practical steps presented in this book so far. Sometimes a single sentence can bring about the solution to a specific problem you are wrestling with. Who knows? Perhaps you’ll find this sentence somewhere in this appendix.

How Your Startup Could Make a Billion Dollars

Most entrepreneurs say money is not a motivation for them. I believe this is true. Financial reward alone is insufficient to instill in you the entrepreneurial fire that will push you forward in rough times. A paycheck will motivate you enough to complete a certain task and then leave the office at five o’clock, but you will rarely compete on a global scale this way. At the same time, it would be nice if your entrepreneurial efforts paid off as well. If you have been working 100-hour weeks for several years without much to show for it, you will undoubtedly ask yourself if this is worth doing. If you have a PhD, you will wonder whether your friends who took cushy jobs at a university or consultancy made the better choice. In such cases, you may briefly think of other entrepreneurs for whom such toil paid off handsomely. The prime example is Mark Zuckerberg, who is now worth about $28 billion.1 Many others exist, and not only in the tech space. How did they get there? Which forces did they leverage to attract such massive wealth? Here is an attempt at an explanation.

Overcome Social Norms

Mark Zuckerberg earned about $3 billion on average each year over the last ten years. Is this possible by playing nice, obeying all the rules, and making many friends along the way? Author Martin Fridson finds that the two primary obstacles to amassing a billion-dollar fortune are the menace of competition and the obstacle of social conventions. To enter the billion-dollar club, entrepreneurs must overcome market forces and conventional wisdom. Walmart founder Sam Walton violated the age-old convention of cordial relationships with sellers. He went around the wholesalers and bought directly from manufacturers. Not only this, but Walton publicly stated that he stole all his good ideas from competitors. He broke the social norms expected of a business person, and Walmart pulled away from the pack.2

Social conventions come in many forms. They often brand becoming wealthy as a crime. Ask anyone if they believe it is ethical to travel by private jet. They may consider this snobbish and wasteful, which is the expected answer that most people are comfortable with. But will being compatible with the majority help you if your goal is a billion-dollar company? You will never be able to attract this kind of money with conventional wisdom. This is by no means a value judgment about people’s personal opinions, just a simple statement of the mindset needed to earn a massive fortune.

Do Something Old, and Do It Better

Many startup entrepreneurs think they have to do something no one else has ever done before. They believe that success comes down to creating an entirely new product that serves a new market. Coming up with a disruptive invention may be one path to a billion-dollar company. But Twitter founder Evan Williams disagrees. He believes that success comes down to fulfilling age-old needs, but in a better way. In a speech, he mentioned the example of car-sharing service Uber, which is valued at $18 billion at the time of this writing.3 The need to get from A to B is by no means original, yet the popular app manages to connect passengers and drivers more effectively. Compared to hailing a cab the old-fashioned way, Uber took out several steps in the process and streamlined the experience. In Williams’ view, the Internet is just a machine that gives people what they want. Instead of a utopian world, it is simply a tool to do old things in a better way.4

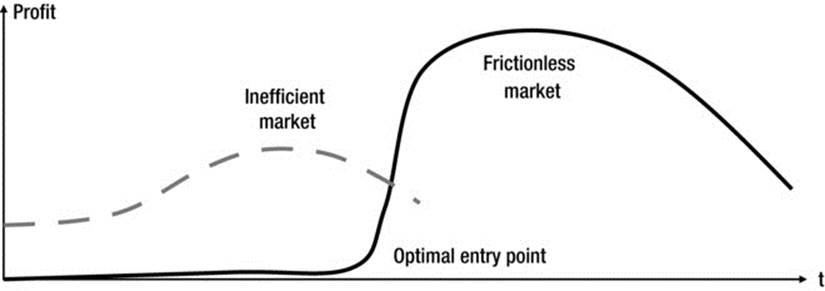

Create Frictionless Markets

Software, technology, and automation have removed much friction from processes that were previously cumbersome. Authors Eric Brynjolffson and Andrew McAfee find that the most radical progress in robotics and 3D printing happened in the last few years, after a frustratingly long period of slow development. The advances are opening the door to near-frictionless markets in various applications that were previously safe from automation. The authors point toward middle-class jobs like medical diagnostics and low-skilled manual labor like picking fruit, which computers and robots could soon automate away.5 Technology reduces inefficiencies and cost, and increases transparency. The same goes for the rapid digitization that is taking place today. Sharing digital files is much easier than distributing physical product. This happens online, where file sharing disrupted the music industry to the core. The communication industry also took a hit: worldwide video conferencing is now freely available to anyone through Skype. When technology takes over, network effects kick in, and change speeds up even more. This allows the newly emerging frictionless market to produce more profits than the market it replaced (see Figure A-1).

Figure A-1. Higher profits in technology-enabled frictionless markets

If your company replaces established processes with new technology, it could potentially earn billion-dollar revenues. Timing is obviously crucial, because the old market may be too powerful to suppress the new technology, or people may be unwilling to give up their established habits. The technology may also still be on the flat part of the curve, not yet ready to deliver the promised gains in efficiency. But when you hit the right entry point to launch a disruptive product in the market just where the exponential curve takes off, then chances are high you will succeed. Hitting this ideal entry point is probably more an art than a science, and it is easy to spot in hindsight.

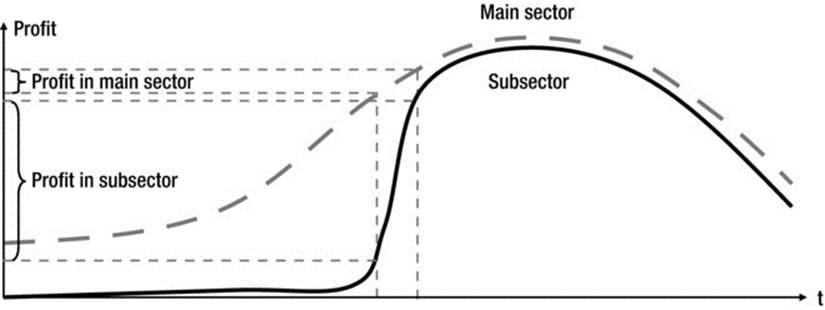

Ride the Market Expansion in a Subsector

Addressing an existing market and riding its current growth rate has a small chance of making you a billion dollars over night. It may allow your company to become profitable over a long period of time. But unconventional returns require massive leverage. Author and venture capitalist Damir Perge reminds us that in certain subsectors of an existing market, the rate of change is much higher than in the main market. Just like in frictionless markets, if you catch the right entry point, your company can surf a large expansion of that subsector, which happens very quickly.

Compare the social media sector with the mobile social media sector, which has witnessed an explosion in the past two years. Social media grew rapidly, but the newly emerging subsector grew much faster.6 An example is the mobile social messaging app WhatsApp, which Facebook bought in 2012 for $19 billion in cash and stock.7

Tesla Motors is another example. After becoming an innovator in the hybrid automobile sector, a subsector of the automobile industry, the company went public and now has a market cap of close to $30 billion (Q3, 2014).8 Riding the market expansion in a subsector looks something likeFigure A-2.

Figure A-2. Comparison of profit in the main sector and a subsector

If your product exists in an established market but serves a newly emerging subcategory of the existing base of customers, then explosive growth is possible. This is incredibly hard to engineer and plan but always easy to explain in retrospect. One thing is certain, though: if you find out your product serves a declining established market, then the chance for explosive growth is small.

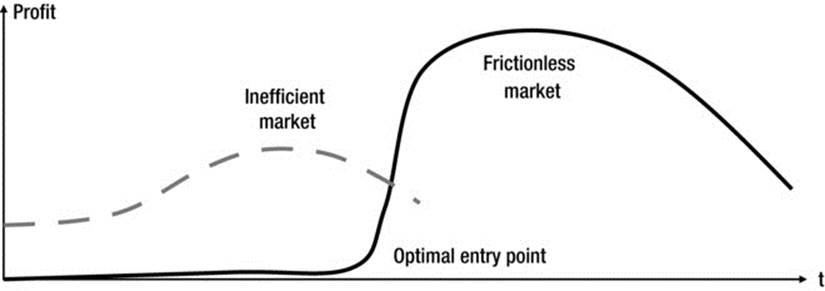

Take Advantage of Disruption

A common case of market disruption takes place when governments privatize certain sectors. After the Cold War, the energy industry in Russia underwent rapid privatization, in the process minting many billionaires. Legitimate or not, the privatization process explains how immense wealth can flow to a single person. Whenever a legacy market becomes stale and inefficient, after a sustained decline in profitability, new players come in through deregulation or privatization. These new players introduce free-market thinking into the former state-owned enterprise and bring it back up to speed. The following recovery of the market is profitable. Market A in Figure A-3 serves as an example.

Figure A-3. Disruptions of a market

A crash is another example of market disruption (market B in Figure A-3). Prominent market crashes occurred at the beginning of the Great Depression in 1929, the Asian financial crisis in 1997, and the global financial crisis in 2007/8. In a market crash, a fire sale of distressed assets takes place. Newly available assets often look unattractive at first sight, because they are rundown, deep in debt, or otherwise considered worthless. However, what could be easier than buying an asset that nobody wants, and later selling it when everybody is clamoring for it? Not every disruption scheme ends in billion-dollar success. But it is a mechanism that has enough leverage to enable it. Anyone with sufficient courage and liquid funds can potentially buy low and sell high when a market crash occurs. If they pick the right assets and play it smart, they make headlines and the Forbes list a few years later.

Launching a startup in times of crisis is a good strategy. If the venture is agile, it can take advantage of market disruption and inexpensive assets in the crash. While everybody else is scrambling to keep their existing operations running, startup entrepreneurs can build theirs from the ground up. They can incorporate lean principles and low overhead into the company from day one. When the economy inevitably picks up again, they are in an ideal position to reap the rewards with high profit margins.

These concepts explain only a few of the mechanics that underlie billionaire wealth. It is obvious that becoming a billionaire is no small feat. These examples make it apparent that there is much more to it than working hard and paying your dues. Most of all, achieving massive success forces you to become an extreme individual. A group thinker has never achieved great wealth. Nor has someone too concerned with what others think about them. Making up your mind to become successful and super-rich subordinates all else. Whether this is advisable is another question. It requires intense focus that dominates your entire life. This will inevitably alienate some of your old friends, and it will make you a target for envy and ridicule—until, of course, you have achieved your goal.

Where Does Entrepreneurial Success Come From?

What primes startups for success is a matter of heated debate. There is obviously no sure-fire recipe, no ten-step plan that makes a fledgling venture the next Google. Here are some thoughts about what may cause a startup to gravitate toward success or failure. This may be helpful for entrepreneurs, universities, and investors alike.

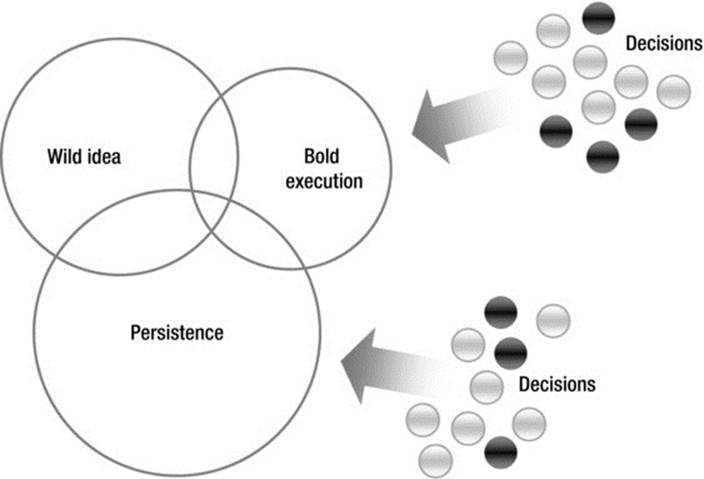

On their journey, successful entrepreneurs need three main ingredients as fuel in their tank: a wild idea, bold execution, and persistence. These three ingredients combined make or break the project. By a wild idea, I mean a slightly controversial hypothesis. If the idea is so mainstream that everyone will accept it, then chances are high that someone else is already working on it. As explained by author Derek Sivers, a brilliant idea with weak execution may still yield profits, as may a weak idea with strong execution.9 To find a superstar, all three ingredients have to be of top pedigree. The quality of execution and persistence are in turn influenced by an entrepreneur’s decisions about how to approach them. As illustrated in Figure A-4, these decisions can be good (light gray dots) or bad (black dots), and they influence execution and persistence.

Figure A-4. Main ingredients of a startup and forces that influence them

Once an entrepreneur has an idea, they must transform it into reality. This is where execution and persistence come in. Startup success often boils down to why and how founders do something, rather than what they are doing. This book has addressed the what sufficiently up to this point. Instead of locking onto the words execution and persistence, let’s examine the forces that influence them (the how and why).

Success Parameters

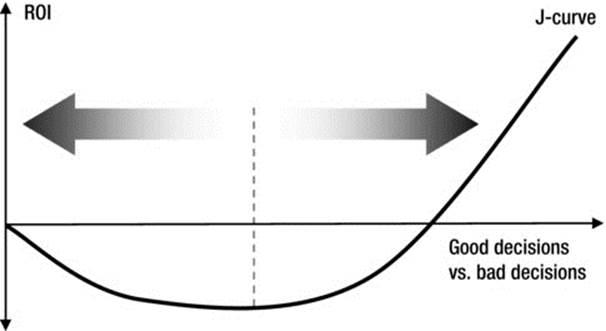

Startups move along a so-called J-curve, where we expect a return on investment down the road after early losses. The pace at which they move along the x-axis depends on a tug-of-war between the entrepreneurs’ good and bad decisions (along the large arrows in Figure A-5). As described by author Jeff Olson, a series of small good decisions, followed up persistently, will yield good results in the long term, whereas small bad decisions, followed up persistently, will yield weak results.10

Figure A-5. Impact of decisions on return on investment (ROI)

Every entrepreneur and investor will of course prefer good decisions, which I believe are a result of the following underlying factors: strong intrinsic motivation, an open mind, and a can-do attitude. What exactly does this mean?

Strong Intrinsic Motivation

In contrast to extrinsic motivation, where external factors like reward and punishment are the driving forces behind taking action, intrinsic motivation comes from within a person. It is a burning desire to reach a goal, no matter what it takes. There is a difference between wanting to succeed and committing yourself to success. If you have the motivation to achieve a goal, there is no reason you cannot make it happen. A desire to prove yourself or a competitive drive for excellence may push you to aim for the gold. Entrepreneurs give themselves every reason to get up in the morning. The desire to do and achieve always trumps a feeling of obligation or fear.

An Open Mind

Invariably, a startup will encounter roadblocks. The technology on which the main idea builds may flounder. There may be legal hassles, or blatant flaws in the original business model may emerge after you work on your startup for a while. To admit you were wrong and to change your mind is easier said than done, because most humans feel they must be consistent with whatever rules they have set up for themselves. But this is definitely not the case for a successful entrepreneur: if the entrepreneur has a change of heart, pivoting will move the startup forward. Resisting the pivot will set the startup on a negative trajectory. Keeping an open mind will allow you to look past conventions and strict rules. You will see what others don’t. If you can only get there with a pivot, then embrace it despite conventions or prior commitments.

Can-Do Attitude

This is the entrepreneur’s hallmark. Strongly related to keeping an open mind, the can-do attitude takes it one step further. Suppose an employee has volunteered to do a task over the weekend and shows up on Monday with the task uncompleted. The excuse is that he really tried but simply could not finish. This is such a normal event in most organizations that it may not even register. However, this mindset is incompatible with startups and entrepreneurship. “No” means “maybe,” and “maybe” means “yes”: that is the way entrepreneurs approach things. If you have been an employee, then this shift may not come naturally. You must take full responsibility for all your actions. Henry Ford knew that “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t—you’re right.” You are thinking anyway, so it is better to think you can.

Some of these success factors may seem impractical to you on first sight. Nevertheless, be aware that entrepreneurs compete with other entrepreneurs, not with other employees, and not with other university students or researchers. The two worlds require different mindsets to succeed.

Regardless, even if you follow the recommendations for the three success factors, there are still roadblocks that can prevent success from taking place. You must avoid those. What puts the brakes on startup success? Financial desperation, analysis paralysis, and a can’t-do attitude.

Financial Desperation

As you already know, intrinsic motivation always trumps extrinsic motivation. If you desperately need to earn an income fast, this may be to the disadvantage of your startup. When you have heavy impending overhead or debt payments, you should find a high-paying job and follow entrepreneurship on the side. The same goes for partnering with co-founders: if one of them has money woes, stay clear. This advice may not sound sensible, but ignoring it has led to trouble for many founders.

A startup needs considerable goodwill along the way to succeed. There is of course nothing wrong with following a profitable idea just for the sake of profit. But if a founder displays money-mindedness as their leading motivation, this will alienate honest backers and attract people with questionable motives. Here is a simple rule: only if you would trade places with somebody, ask them for advice or work with them. Those with money woes will automatically fall through this screen.

Analysis Paralysis

Especially in academic circles, analysis paralysis runs rampant. Have you already spent so much time analyzing a situation that you have lost sight of what to do next? How many more PowerPoint presentations and data visualizations do you need to convince yourself and take action? Academics often confuse a startup with a thought experiment. However, entrepreneurship has little to do with writing an academic paper, where at the end of the process a group of experts either approvingly nod or reject the idea. Startups are often irrational endeavors whose fate is decided by volatile market forces, not all-knowing gatekeepers.

Most worthwhile ideas were at some point rejected by experts. If you must convince others, then let them be people on the same wavelength as you. If you lack conviction and feel you must convince yourself to the degree that it hampers your ability to take action, then check whether you are really on board with the idea. You may find that you hold doubts about it that prevent you from moving along. However, if your environment has dragged you into a negative feedback loop, read the next point.

Can’t-Do Attitude

If you think it cannot be done, then you will prove yourself and your peers right. This belief may have grown in you over the years. Be aware that it is hard to thrive as an entrepreneur in an unsupportive environment. Influence is a subtle process: peers are rarely outright hostile. Slight criticism, a raised eyebrow, or a smug remark here and there when you speak about your ideas can have enough cumulative abrasive force over the years to grind away your entrepreneurial spirit. This happens without your knowing it. Be selective about your associations, and make sure they are encouraging and positive.

If a startup begins working on a wild idea and follows up with strong execution and dogged persistence, the main ingredients for success are in place. If an entrepreneur repeatedly makes good decisions, the gears are set in motion to reach escape velocity. To understand how the entrepreneur is thinking, find out whether they display a strong intrinsic motivation to make the idea succeed, an open mind to pivot when necessary, and a can-do attitude to combat adversity. Look at factors that may hamper success: whether there are extrinsic motivators that are misaligned with entrepreneurship, a lack of conviction to run with the idea, or a negative attitude that turns the entrepreneur into their own worst enemy.

Use this checklist to assess your own situation. Also be aware that venture capitalists look at similar factors to assess you and your idea. Of course, making better decisions is desirable for more than just startup success. If you can enable positive forces in your life that automatically guide you toward making better decisions, both you and your startup will be happier.

Stop Pitching Ideas

In the past, I have heard pitches of “the next big disruptive idea,” “the future of social networking,” and an idea “ten times better than Facebook” (seriously, I am not making this up). Entrepreneurs seek to attract capital with these claims (venture capital or angel funding), to make their projects reality. The point they often miss is that pitching ideas is a waste of time and a huge turnoff to experienced investors. Pitches may be amusing, but they can shut investors’ doors before the first MVP has been tested.

By pitching ideas I do not mean talking about a fresh idea with a friend and asking for their feedback. I mean the belief that an idea alone is enough to attract investment. You learned throughout this book what it takes to engage third parties with confirmed value propositions. If you stick to what this book suggests you do, you will never feel compelled to pitch ideas.

During the dot.com boom ten years ago, the story was a little different: getting an online presence required making an upfront investment in server infrastructure, paying database license fees, and hiring an experienced staff that was hard to find. The initial costs of an Internet startup could amount to $1 million. Luckily, we face an entirely different reality today: cloud and scalable VPS hosting, even designated servers, can be had for less than $100 per month. CMSs and databases are a dime a dozen; most businesses can pick from a wide offering of free open source or inexpensive solutions. Relevant experience is also much easier to find: basic coding and front-end user experience are simple with WYSIWYG and widget programming. Job fairs like elance.com and odesk.com offer competitive skills for hire. Rapid prototyping is quickly becoming the norm, with workable prototypes available for less than $50.

We talked about the importance of the minimum viable product throughout this book. If you are an entrepreneur, you need a prototype today. If you are still pitching ideas to attract investment, no matter how sophisticated your pitch deck and the financials look, it will be hard to obtain funding. More important than putting together that killer presentation is getting started and leaving the building to test your hypothesis in the market. Once you have a couple of prospective clients for your product, you can begin to iterate, tweak, and jumpstart grassroots marketing efforts. It is not rocket science to put an idea on the ground and test it, and investors want to see entrepreneurs do exactly that.

Expertise Is the New Venture Capital

Because almost no investment is required to found a startup, it has become more critical for young companies to focus on finding advice about product development, scalability, and marketing. An experienced entrepreneur or investor can provide you with a professional network. This is usually more important than funding. If your MVP shows initial traction, you have much more leverage to attract qualified advice. To come across as a doer, not a talker, you must prove you can deliver. And when you do that, you are no longer pitching ideas. Only then can you engage others to get on board with you who can help your startup.

Why You Cannot Replicate Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is the nickname for Santa Clara Valley, the South Bay portion of the San Francisco Bay area in northern California. In the last years, the term has become a synonym for innovation. Research parks often dream out loud of copying Silicon Valley. Occasionally, someone makes the mistake of publicly declaring that they will take it on head to head, only to silently fade into oblivion a few short years later. Moscow’s Skolkovo innovation center is a legendary example. Billions of rubles flowed into an entrepreneurship and research hub dubbed the “Silicon Valley of Moscow,” with little certainty of success.11

Even the residents of Silicon Valley struggle to explain how its success came about. According to author Deborah Perry Piscione, we have to go back to the year 1884, when Leland Stanford thought about what a university in his son’s honor could look like. Piscione goes on to explain several ingredients of the success story that is Silicon Valley.12 Let’s look at some of them and examine the three main building blocks that made Silicon Valley what it is today.

Stanford University, the “MIT of the West”

Stanford University, located in the north part of the valley, has been one of its defining elements. Its founder, Leland Stanford, insisted that “science provide direct usefulness in life,” which put the university in a league of its own. Stanford now runs its own industrial park, which over 150 companies call home. Most other universities ignored the relevance of science at the time, and, unfortunately, not much has changed in the meantime.

After World War I, the U.S. military granted $450 million (in 1945 dollars) to weapons R&D. Several universities on the East Coast (such as Harvard and MIT) shared this money. But only $50,000 found its way to Stanford University, which at the time lacked the reputation of being a credible research center. Frederick Terman, then Stanford’s chair of engineering, felt so personally offended that he vowed to recruit away from East Coast universities the best research talent available. He transformed Stanford into the “MIT of the West,” as author Steve Blank puts it. When the Cold War intensified after 1950, Stanford University became a full partner with the military, the CIA, and the NSA.

Stanford researchers routinely work with industry as paid consultants. This not only ensures that the latest technological know-how finds its way into the market, but also channels insight about business and industry trends back to students and researchers. So far, the university has spawned more than 6,000 companies.13 Some of them include Charles Schwab & Company, Cisco Systems, Dolby Laboratories, eBay, E*Trade, Electronic Arts, Gap, Google, Hewlett-Packard, IDEO, Intuit, LinkedIn, Logitech, MathWorks, Netflix, Nike, NVIDIA, Odwalla, Orbitz, Rambus, Silicon Graphics, Sun Microsystems, Tesla Motors, Varian, VMware, Yahoo!, Zillow, and Instagram. Together they amount to hundreds of billions of dollars of market capitalization.

U.S. Military Funding Started a Chain Reaction

Most people believe the United States is leading the technology sector because of fiercely independent entrepreneurial minds. In reality, the government created all these sectors with a heavy hand that had a big influence on the destiny of Silicon Valley. By transforming hundreds of acres of farmland into a hub of cutting-edge military technology, the U.S. Navy built Moffett Federal Airfield at the southern tip of San Francisco Bay in the 1930s. Large-scale subsidies from the military enabled the thriving electronics and semiconductor industry. The Internet emerged from a military research project. Heavy military funding started a chain reaction that led to the Silicon Valley we know today.

The electronics industry transformed the valley into a hotbed of innovation with Hewlett-Packard (HP) and Varian as its biggest success stories. They went public in 1956 and 1957 as the first Silicon Valley companies in history. Shockley Labs, set up in the heart of the valley, was the first company to work on silicon semiconductor devices and gave the region the nickname Silicon Valley. Its eight leading scientists later left Shockley together to create a joint venture with Fairchild Semiconductor, which revolutionized the chip-manufacturing industry. Many of the original founders of Fairchild Semiconductor set out to start their own companies in Silicon Valley: for example, Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore started Intel, and Jerry Sanders and John Carey started Advanced Micro Devices (AMD). These new companies had inclusive cultures with flat hierarchies and in many ways created a new generation of companies.

The Growth and Profitability of Venture Capital

Wealthy investors became interested in Silicon Valley after the first successful IPOs in the electronics and semiconductor industry. The passage of the Small Business Investment Act in 1958 enabled the large-scale financing of small entrepreneurial businesses in America. Another milestone was the establishment of the limited partnership as a business structure in the 1970s. This provided an opportunity for general partners of venture capital funds to legally charge a 1–2.5% management fee of the investment capital raised. In addition, they charged a 20% fee on all profits of the fund. This is the venture capital model still in existence today.

It becomes apparent that the birth of Silicon Valley was not an overnight affair. In fact, it took more than 100 years to transform an area of farmland into the epicenter of innovation we know today. Not only were large-scale military funding and government protectionism a big part of it, but much luck and serendipity played into this success story. When a government announces that it will build “the Silicon Valley of XYZ,” then we must assume they turn a blind eye on history. Many puzzle pieces fell into place over decades to make it happen. None of them would have worked out of context in a different environment to quickly force the same ecosystem into existence.

If you have ever been in Mountain View, you notice that there is a certain energy in the air. A few millions, even billions, cannot buy this energy. It cannot be summoned by willpower. No government can legislate it into existence. And no university can just say it would like to have this energy and make it magically appear.

Forget about comparing universities or research parks with Silicon Valley. By aiming at the Sun, you may end up on the Moon, this is true. But there are other proven ways to make startup entrepreneurship work. Simple, practical steps have led to success in hundreds of startups, and some of them are outlined in this book. Begin applying them one by one, without trying to reinvent the wheel. Then your university and your startups will succeed.

____________________

1Forbes, The World’s Billionaires: Mark Zuckerberg Profile, www.forbes.com/profile/mark-zuckerberg.

2Martin S. Fridson, How to Be a Billionaire: Proven Strategies from the Titans of Wealth (New York: Wiley, 2009).

3Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Why Uber Might Well Be Worth $18 Billion,” New York Times Dealbook, June 9, 2014, http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/06/09/how-uber-pulls-in-billions-all-via-iphone.

4Ryan Tate, “Twitter Founder Reveals Secret Formula for Getting Rich Online,” Wired, September 30, 2013, www.wired.com/2013/09/ev-williams-xoxo.

5Eric Brynjolffson and Andrew McAfee, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2014).

6Damir Perge, “Build a Billion Dollar Startup Almost Overnight,” video series, entrepreneurdex, July 25, 2013, www.entrepreneurdex.com/video/how-to-build-a-billion-dollar-startup-almost-overnight-pt-1.

7Facebook, “Facebook to Acquire WhatsApp,” Facebook Newsroom, February 19, 2014, http://newsroom.fb.com/news/2014/02/facebook-to-acquire-whatsapp.

8Yahoo Finance, “Tesla Motors, Inc. (TSLA)”, http://finance.yahoo.com/q?s=TSLA.

9Derek Sivers, Anything You Want: 40 Lessons for a New Kind of Entrepreneur (The Domino Project, 2011).

10Jeff Olson, The Slight Edge: Turning Simple Disciplines into Massive Success and Happiness (Atlanta: Success Books, 2005).

11Isabel Gorst, “Massive Funds for a ‘Silicon Valley’ Lookalike, Financial Times; October 18, 2012, www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/67850d9c-1480-11e2-8cf2-00144feabdc0.html.

12Deborah Perry Piscione, Secrets of Silicon Valley: What Everyone Else Can Learn from the Innovation Capital of the World (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

13Stanford University, Wellspring of Innovation, www.stanford.edu/group/wellspring.