University Startups and Spin-Offs: Guide for Entrepreneurs in Academia (2015)

Part I. Strategies for University Startup Entrepreneurs

When did you choose to become an entrepreneur? In early childhood, or just yesterday? Or are you still on the fence? Whatever the case, you should have some idea about what it is like to start your own business before you take the plunge—an idea based on the entrepreneurial experience of someone who has done this before.

If you study or do research at a university, take a step back and observe your environment from 50,000 feet in the air. You see a fail-safe system where you acquire deep knowledge without much distraction. It does not matter whether the economy is in a boom or in a slump; learning always has priority. Now think about what this environment could do for you as a startup entrepreneur. You have a strong community, an excellent network, diversity of ideas and opinions, fully equipped workshops and labs, and tech support at your disposal—all for free. Your university may have a strong reputation. It may attract powerful external parties such as governments and corporations that want to be involved in one form or another. All these advantages are unique, and they exist only for students and researchers. In this walled garden, you can test and experiment. If you fail, there is almost no consequence. Companies seldom have such luxury. University startups have a leg up on anyone else. When you know how to use this environment to your benefit, you can compete with companies anywhere in the world from a strong base that supports you all the way. Why not give it a shot and make the most of your university experience?

Most of the time, your university or government will have some startup advice for you. This is the conventional advice that others have diligently followed: apply for this or that grant, participate in the business-plan competition, and get some MBA students from another faculty to create a business model for you. The startup consultant from the university or the government has never launched a startup, so how can they be experts to guide you toward success? Out of ignorance about what entrepreneurship really entails, startups give away much of the control over their destiny.

Part 1 of this book will empower you with actual, practical steps that you can apply today. Of course, this is no guarantee that your venture will succeed. Nevertheless, it is much better than having no clue about how to begin, in the process relying on non-entrepreneurs to call the shots for you. I have included a few episodes from my own startup journey. They have little in common with the success stories you would read in a Donald Trump book, but they paint a picture of what most entrepreneurs may go through to eventually turn their companies profitable. To make the point that successful startups are not created overnight, let me recount how my first company came to pass in a little more detail.

When I started out as an entrepreneur, I had the odds stacked firmly against me. Nobody from my family had ever started their own business. None of my friends had, either. Because I thought I wanted to be a medical doctor from a very young age, I never seriously looked at any other professions. Not only that, I never investigated what it really meant to be employed in a hospital. After the first year at medical school, I terminated my studies with the vague idea of doing something with the Internet and multimedia. All of my old friends from school reacted to the decision with disbelief and criticism. The same was the case with the new friends I had made during my freshman year. Nobody could quite understand why this guy was dissatisfied with what worked so well for them. Why did he decide to give it all up to try to do the impossible? My parents were obviously less than thrilled when they heard of my latest plans. They were not particularly supportive of this new direction, yet they had no other choice than to let me try.

Because I was not independently wealthy, I had to take on some humbling, menial jobs—just menial enough that I had enough time to develop my vision and skill set in my free time. The first was part-time work as an usher in a movie theatre. Occasionally some old classmates would see me vacuuming popcorn from the floor; they must have chuckled at the sight of the valedictorian of their class from the prestigious high school, the former medical student, who was now laboring side by side with shady characters, some of whom you would rather not face at night in a dark alley. This was a difficult time, no doubt. But in retrospect, it was an essential test of my dedication to make it work.

With the little money I had saved, I bought a desktop computer and picked up some programming on my own. After a brief stint at a copy shop (where I learned to use Adobe Photoshop), I took a part-time job at a TV station (where I learned about marketing and using multimedia software). A few more interludes followed, most of them hardly worth recounting. However, after about a year, I felt I had enough knowledge to launch my first startup. The Internet was just beginning to take off, and there was a fast-growing demand for flash web sites with audio and CD-ROMs with sound effects and narration. This is what I offered to produce as a service. I was 22 years old, with no experience, let alone a track record. As you might expect, I blundered my way through many embarrassing episodes. One of them was the brilliant idea of making a big marketing splash by sending 100 potential clients little boxes of chocolate with my business card inside. After a few days, I called the clients and asked whether I could come by for a meeting to show my services. It turned out to be an unusually hot summer. Someone at the post office must have parked their delivery truck in the roasting sun. You can imagine what those well-intentioned presents looked like when they arrived at the clients by mail. It was an expensive marketing stunt gone wrong.

Finally landing my first paid project put the gears in motion. The Internet was rocket fuel to the economy, so more projects followed in swift succession. All in all, I have to admit I was lucky that this first startup was successful. Many other entrepreneurs went under in the first dot.com crash. Their founders had come from much more privileged backgrounds than me. Some were MBAs; others were launching their second company with powerful joint venture partners and ample funding. Because none of that was available to me, I had to be creative and resourceful from day one. Had I relied on my surroundings and waited until someone took me under their wing to make things happen for me, I would not be writing this book today. Through trial and error, I found an approach that helped my company become profitable fast, with products that clients paid money for from the start. This trial phase is something I still draw from today. Some of the startup advice in this book is directly related to it.

Fortunately, it got easier over time. With more experience, I put less trust in those who insisted that starting a successful company without funding was impossible, perhaps because I knew that it could be accomplished. Not all my ventures were profitable, but the failures were just as valuable as the successes.

An iron will and common sense go a long way. Unfortunately, these are what I see lacking with many of today’s startup entrepreneurs. A flood of recent business literature gives founders the impression that they have to study entrepreneurship before they can do it. Grant programs, government initiatives, and startup workshops saturate them with theory, taught by people who have never started a company themselves. Media stories about recently minted billionaire founders are selling the Hollywood version of entrepreneurship. Please do not buy into this hype.

Entrepreneurs have always existed, and to launch a thriving business is doable with little theory if you put your mind to it. It was possible before any government grants existed and before venture capital and seed accelerators arrived on the scene. You need the determination to succeed and a few simple strategies. Most important, you have to take action, sooner rather than later. The simplicity of entrepreneurship is its power. This power lies with the entrepreneur alone. As soon as you take matters into your own hands, you will start making real progress toward your own success story.

If you come from an entrepreneurial family, then you have a better chance of making it. But if not, what will you do? Not even try because nobody is helping you? Quietly agree with the opinion of the mainstream that startup success is a lottery or requires an MBA and millions of dollars in venture capital? If your university or government has programs available, then take full advantage of them. But do not let them distract you. If you get on the wrong trajectory early, reaching your destination will be a challenge.

A recurring theme of this book is taking matters into your own hands to move your startup forward step by step. On the way, take advantage of all the synergies you can get. Learn from your mistakes. Pick yourself up and keep walking. Take initiative, and never wait for opportunities to come to you. This is the defining characteristic of a successful entrepreneur.

Chapter 1. The Status Quo: How Do Startups Fit into Universities?

Students and researchers have always founded their own companies right out of universities. This is not new. Just as in any other venture, some of those companies thrive, while others falter. Some entrepreneurs have a natural talent for running a business, whereas others are less skilled. In recent years, there has been a huge surge of interest in entrepreneurship, both inside and outside universities. Researchers are beginning to realize that running their own company may be more adventurous and rewarding than a lifetime teaching position in higher education. Students converge on popular fields such as computer science to launch their own companies while working on their degree or after graduation. News stories abound about 20-year-olds turning into billionaires with virtual reality startups.1

Entrepreneurship has attracted global buzz. However, when it comes to practical know-how about launching a startup, universities have much catching up to do. To fill the void, incubators and seed accelerators have sprung up as startup schools that offer crash courses in entrepreneurship, infrastructure, mentoring, and financial aid.

Before you jump in and learn about the practical guidelines for entrepreneurs, you first need to understand the place of startups in universities today. This chapter explains the components that enable startup success, how they interact with each other and how universities currently put them to use. It also outlines the launch sequence of academic startups and the roadblocks entrepreneurs encounter, Later in this book, we will look into some of the support systems available for startups, such as entrepreneurship programs, technology transfers, and startup grants. The discussion would be incomplete without deliberating on why some of these programs are useful and others less so. This chapter also introduces the main obstacles that stand in the way of setting up effective startup programs at universities, and common misconceptions about startup entrepreneurship in general. This groundwork sets the tone for the rest of this book. Without it, I feel entrepreneurs have only half the picture of what it means to launch a company. Examples for upgrading a university’s startup program are in the second part of this book.

Universities Can Build the Optimal Startup Ecosystem

Universities are still the undisputed centers of excellence when it comes to knowledge and scientific research. But using their assets in the marketplace is not their strength, and, unfortunately, the impact of scientific research on the lives of people outside of academia is small. This is unnecessary, because universities occupy an important space at the intersection between science, business, and public policy. They connect many stakeholders from different domains in their daily activities. Some universities have a high pedigree and an international reputation that draw attention from financial investors and the media. They participate in summits such as the World Economic Forum (WEF), world city summits, and climate conferences. Universities often interact with multinational companies that sponsor their research. And the government is also on board as principal financier.

Despite the fact that opportunities for network building and cooperations are readily available to them, universities hardly use them enough for their own benefit. They actively communicate with many third parties, but the energy this creates often evaporates, unused. If universities channeled this energy, they could help create a robust ecosystem for startups, to the advantage of students and researchers interested in entrepreneurship. Such an ecosystem would prepare participants for the journey ahead and would eventually build a bridge between scientific research and millions of people who stand to gain from it in their everyday lives. It would anchor the university in the public image as a force for real-world impact. And it would motivate staff and professors to discover a deeper meaning in their work. Let’s examine what such an ecosystem could look like.

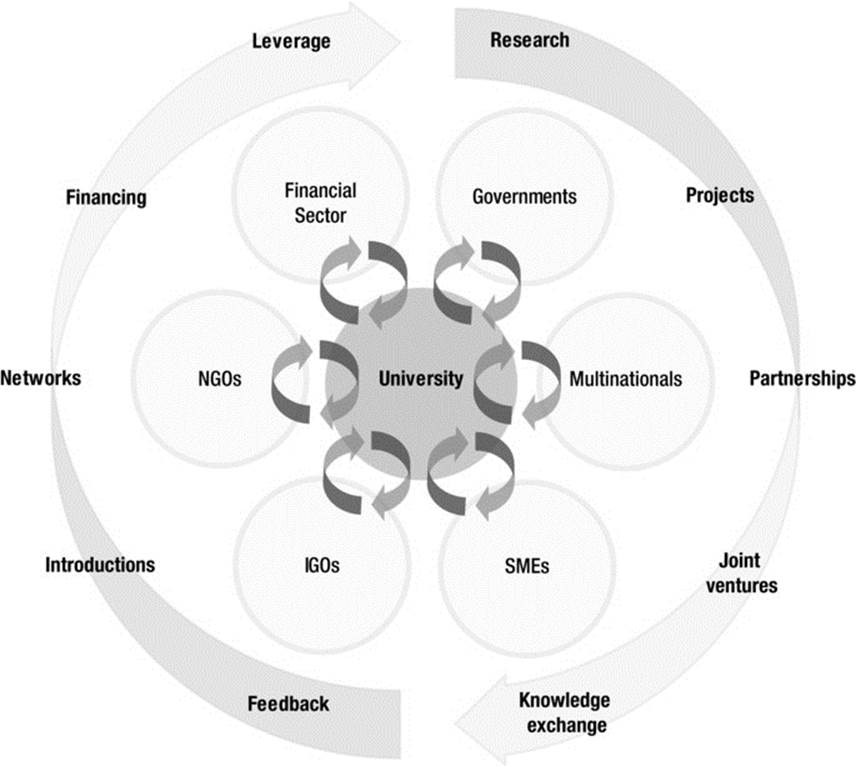

Universities are platforms. Many different stakeholders exchange ideas and energy with universities daily, creating vast potential resources that are just sitting there, unused. As soon as universities focus and channel energy toward their startups, synergies emerge. Dynamic knowledge exchange, collaborations, constant feedback, and engaged discussions grow a ring of network effects around the institution (the large arrows in Figure 1-1).

Figure 1-1. Ideal university ecosystem and resulting synergies

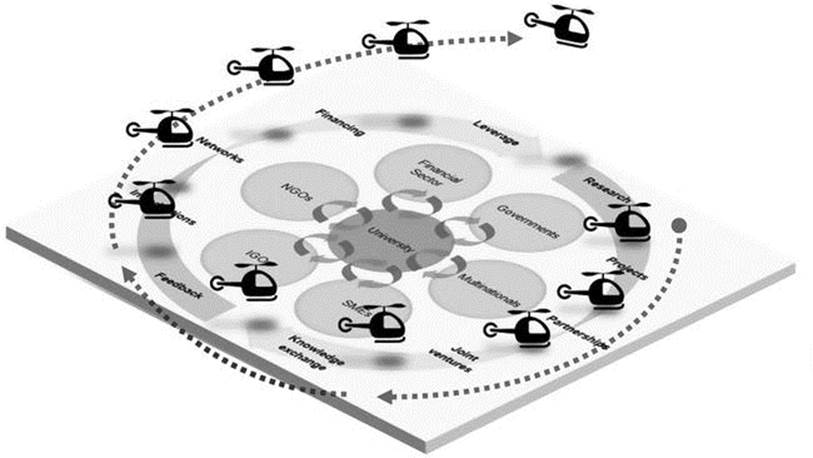

With the energy and momentum available on this supercharged platform, startups load their batteries and eventually lift off like helicopters. Figure 1-2 shows what the ideal situation looks like. A university with a strong entrepreneurial ecosystem is the ideal launch pad for startups founded by students and researchers. Most universities have all the components to build it right in their backyard. They just need to remove the blockages that prevent the ecosystem from growing. Academia is a natural magnet for smart people and interested external stakeholders. As soon as their energy is channeled toward a common goal, startups in this environment draw on much stronger resources than the private sector alone can provide.

Figure 1-2. The university ecosystem turns into the ideal startup launch pad

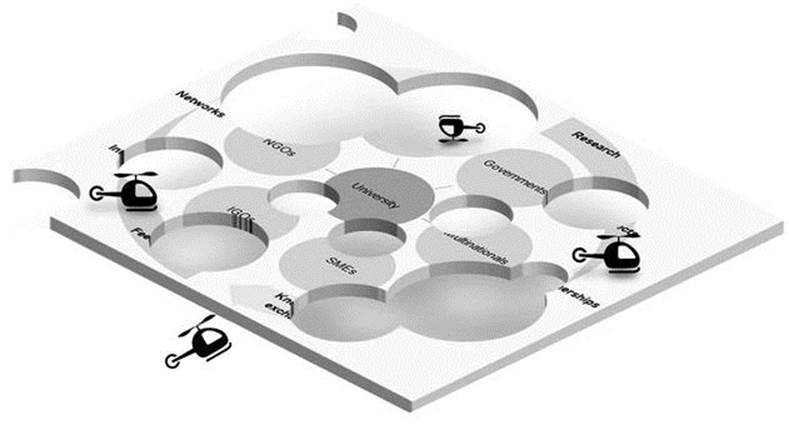

However, such ecosystems are still nascent or nonexistent. A few global hotspots have managed to create them over the last couple of decades, but one can count them on the fingers of one hand. At present, most synergies lie dormant, and startup launch pads are not fully formed. To understand what this does to university entrepreneurship, look at Figure 1-3, which illustrates the current, incomplete version of the launch pad.

Figure 1-3. Startups on the incomplete launch pad

The status quo looks much less inviting. A weak entrepreneurial ecosystem leads to a weak startup launch pad. The ring of network effects around the university is interrupted, and no ecosystem can grow. Synergistic interaction with third parties is almost entirely missing, which leads to roadblocks and gaps in the structure. Far fewer startups are possible on an incomplete platform. That is obvious, because there simply is not enough room and energy for them to thrive. Serious pitfalls can hamper startups at any stage of their evolution. Looking at it from this perspective, it is evident why so few successful startups come from academia.

Why don’t universities repair their incomplete startup launch pads? They would first have to grow stronger entrepreneurial ecosystems, and the need to do that is not yet dire enough. In many universities, the opinion prevails that entrepreneurship workshops, business plan competitions, and grant funding will fix the underlying structural problems. However, without a fundamental shift in the way academics and institutions approach entrepreneurship, current efforts will bring mostly cosmetic improvements that only go so far. This is unfortunate. As education becomes increasingly globalized, it will be critical for universities to adopt entrepreneurial thinking and have something to show for it. It will no longer be sufficient to point to key performance indicators (KPIs) that show a certain number of spin-off companies or patent applications per year. Uncomfortable questions about the measurable impact of such startups will surface. This may not happen immediately, but the day will come. Academia will have a lot of catching up to do then.

The good news is that many ideas coming out of universities are groundbreaking. They have the potential to make a difference in the lives of millions of people. With a mind shift, it will be possible to transform the status quo at universities into thriving ecosystems for startups. It will take much effort to put the gears in motion. How universities can do this is the subject of part 2 of this book. Let’s first discuss the necessary steps and the roadblocks on the way to startup success.

The Startup Launch Process

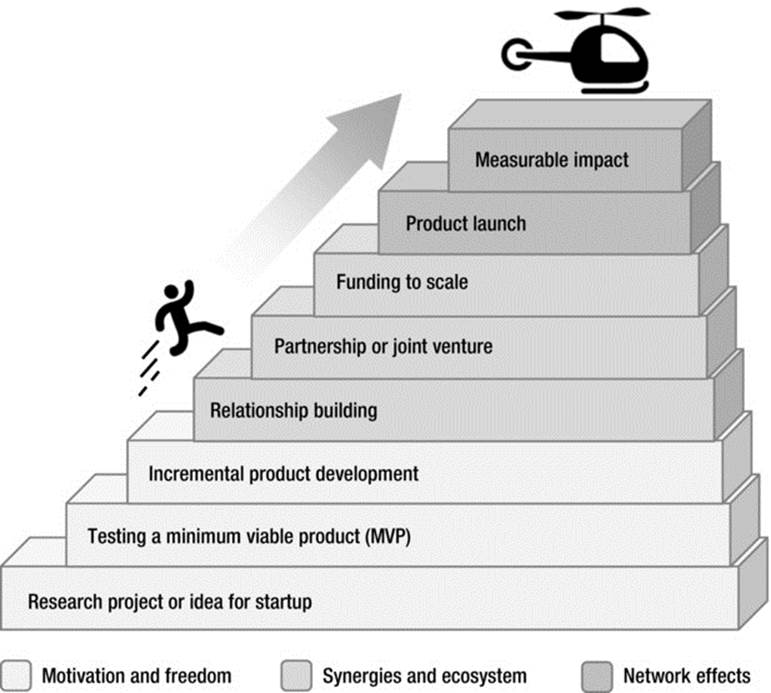

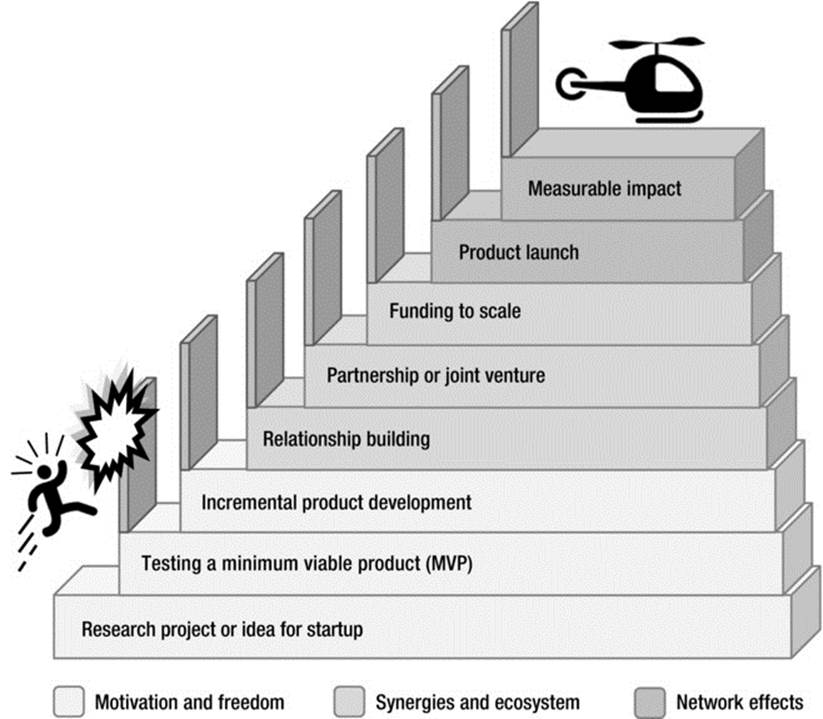

With their natural wealth of resources and synergies, universities should be hotbeds of startup success. Let’s pretend for a few minutes that everything is perfect and universities make the most of the opportunities available to them. Figure 1-4 shows the ideal launch sequence for startups.

Figure 1-4. Ideal startup launch sequence

The underlying forces that enable startup success are as follows:

· Motivation and freedom: Students and researchers have a strong motivation and the freedom to follow through on their ideas for startups.

· Synergies and ecosystem: The university has cleared roadblocks to synergies and has allowed an entrepreneurial ecosystem to grow. Startups draw massive energy from that.

· Network effects: Once enough synergies are in place, network effects kick in. Launching additional startups becomes increasingly easy, and startups stand a better chance of making an impact in the market.

If these forces are in place, the stage is set for startups to take off. How universities may develop these forces is the subject of the second part of this book. For the time being, let’s assume they exist already. In the ideal environment, all that students and researchers need is a practical approach to entrepreneurship. Unless they mismanage their venture in the launch process, they automatically achieve the right trajectory.

To illustrate how the launch sequence works, let’s start with a research project at a university. Assume the team had an idea about a potential commercial product and decides to launch a startup. Empowered to do so, they first test their assumptions. Without testing, the startup would be flying blind. Serious entrepreneurs cannot afford to do that; they need to know if their intended product meets a demand in the market. If enough people are ready and willing to pay money for the product, then there is a business. The startup can charge ahead full-steam and develop the product incrementally. The founders test and re-test their upgrades often with potential customers in the market. In parallel, they begin building relationships with third parties. These may be companies in the same field or other experienced entrepreneurs who have already launched successful startups. The financial sector and wealthy individuals should also be part of entrepreneurs’ networks. The startup engages them all for frequent feedback on their progress and a dynamic exchange of ideas.

Because the founders communicate effectively and professionally, they have a clear understanding of who to approach. They also understand the benefits they provide to third parties. With actionable next steps, they keep them involved and direct all the energy they can into the development of their product. Because stakeholders outside of the university see a value in what the startup produces, they inspire the founders with ideas. When the product has evolved to the point that the startup can launch it in the market, the team brings their connections to venture capital firms to the table. The entrepreneurs can scale rapidly when they need to. Their product serves an existing need in the market, and their business model is strong enough to drive a profitable company. Because they always had an ear to the ground, the launch is a success. The startup transformed university research into a useful product that improves the lives of people. It has a measurable impact on the real world.

Universities and their entrepreneurs should continue to strive for this ideal process. As you already learned, universities can build powerful ecosystems for startups. Once they have achieved that, reality will be closer to the ideal scenario we just described.

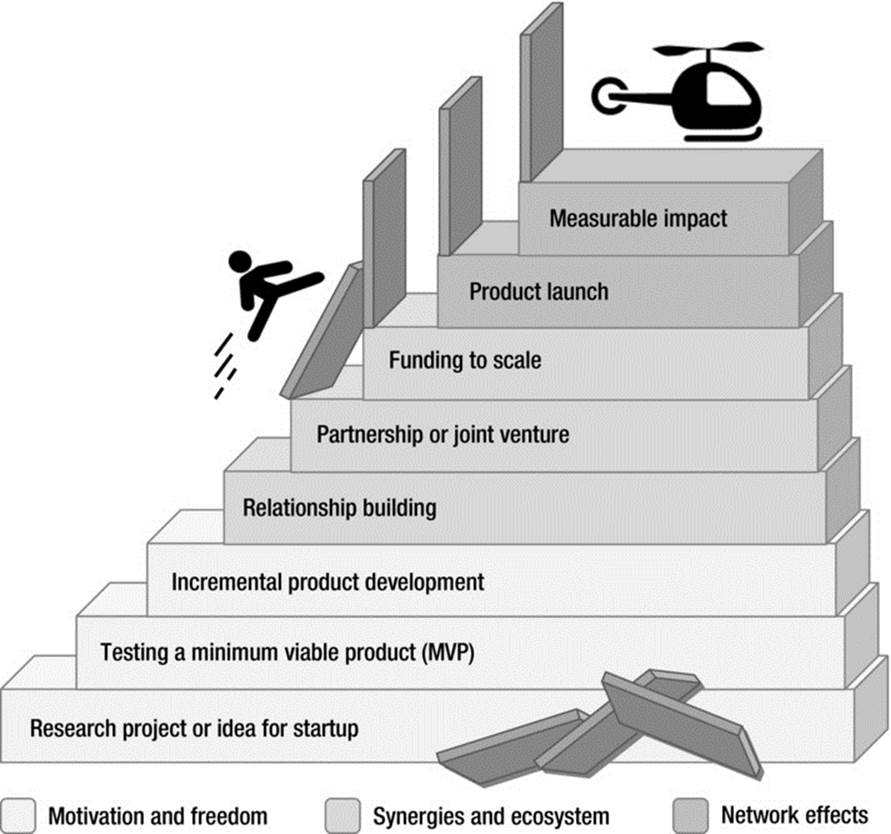

Let’s now take off the rose-colored glasses. Unfortunately, the reality for startups at universities is less than ideal. The experience for entrepreneurs can often feel similar to the illustration in Figure 1-5.

Figure 1-5. Startup launch sequence with roadblocks

Numerous roadblocks prevent startups from moving from one step to the next. Entrepreneurs cannot skip any of the steps of the launch sequence—they are all necessary to build a solid foundation for the startup. Some of the hurdles are external: they exist within universities that are unprepared to give startups what they need. Synergies, the ecosystem, and network effects may be missing. Other hurdles are internal: students and researchers may not know how to advance from one level to the next. They linger in analysis paralysis or lack constructive strategies to express and develop their ideas. They often struggle to define their own value for third parties, let alone engage them in a mutual knowledge exchange. As a result, their networks are not strong enough to help them reach escape velocity. Despite good ideas, many startups are trapped on the ground level. They never launch a useful product, so they fail to attract a joint venture partner or venture capital. Such startups and spin-off companies do show up in the university’s KPIs, but their measurable impact is zero.

So what is there to do? It will take a while for universities to get their ecosystems up to speed. In the meantime, it is up to the entrepreneurs to overcome the roadblocks. More often than not, the prevailing thought is that more money fixes all problems. But instead of paying the roadblocks to go away, startup entrepreneurs need to know practical strategies to overcome them (see Figure 1-6).

Figure 1-6. Overcoming roadblocks with practical strategies

In a less-than-perfect world, students and researchers must take matters into their own hands. Whenever they encounter roadblocks, they should know how to kick them away with the right karate moves. With entrepreneurial thinking at their disposal, they develop products with the lean method. They learn how to articulate their business ideas to third parties outside of the university. This gives them a clear understanding of their value proposition and helps identify the right partners, which helps them to build strong networks with established companies and the financial sector.

When they have to fend for themselves, startups may advance more slowly than in the ideal launch sequence, but they do so steadily nevertheless. They move forward step by step and eventually take off on their own terms. By developing their own powers, entrepreneurs can thrive in today’s less-than-perfect ecosystem. What these powers are and how to acquire them is up next in this book.

____________________

1Alexei Oreskovic and Malathi Nayak, “Facebook to Buy Virtual Reality Goggles Maker for $2 Billion,” Reuters, March 26, 2014, www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/25/us-facebook-acquisition-idUSBREA2O1WX20140325.