University Startups and Spin-Offs: Guide for Entrepreneurs in Academia (2015)

Part I. Strategies for University Startup Entrepreneurs

Chapter 4. Engaging Others with Actionable Next Steps

How many times has this happened to you? A businessperson you meet at a networking event finds your research project interesting and wants to learn more about it. You exchange cards and set up a meeting in the coming week. The person comes to your lab, signs the NDA, and approvingly nods at your technology, which you present in much detail. When the hour is up, your guest thanks you for the time and suggests keeping in touch, especially when you have advanced the technology more and it is closer to implementation. The person then departs, never to be heard from again. You assume this person was not all that interested after all and chalk it up as one more pointless meeting.

In reality, you failed to engage the visitor properly. You were most likely unclear about what you wanted from the interaction in the first place. You showed your work, but you missed the chance to gain insight into the business of your visitor and the person’s challenges, expansion plans, or product innovations. When making a new contact, most people never research who that person really is, let alone read up on their present and past job history or personal interests. Every person has a valuable network, and when you meet someone, you can get access to their network. It may not be the initial contact you do business with, but rather someone on the edge of that person’s network. Entrepreneurs must know how to use others to advance their cause. This is a cornerstone of entrepreneurship.

In your dealings with those outside your university, you should begin thinking about engaging them with actionable next steps. They may be government agencies, financiers, insurance companies, businesspeople, successful entrepreneurs, or others. At a large public university I worked with, several banks scheduled visits to show the impressive infrastructure of the world-renowned institution to their C-level staff and wealthy clients. After the first few tours, the managing director decided to stop the visits with the argument that his facility was not a zoo. With this only half-joking statement, he and his staff got rid of the annoying visitors, but they threw out the baby with the bathwater. Imagine what a good relationship with banks and their wealthy clients could have done for the university’s startups. Many other universities and public companies act the same way every day. Few people know how to engage others with actionable next steps to gain leverage.

By means of “build, measure, learn,” you already know that frequent market testing is required in order to get feedback about your products and services so you can incrementally improve them. You can use interactions with the real world for the same purpose. Instead of giving visitors a feature-laden lecture, why not engage them in a fun experiment that helps your startup collect data about its product or service? Why not ask them questions to learn more about their opinions and interests? It is often possible to turn the situation around and derive a constructive learning session from engagements that at first seem dull and boring.

Know What You Want

You have gained clarity about your startup, your process, some of your first MVPs, and other insights. Now you have a good picture of who to engage for the cause of your startup. In the world of the startup entrepreneur, everybody becomes a potential MVP tester, client, partner, or advisor. Is someone telling you about their children at a networking event? If your startup works on an electric scooter, ask them to bring the kids to the lab to test how it feels to be the underage copilot. Are you programming software for traffic flow, and someone mentions that they know an operator at the transport authority? Ask them to set up a meeting so you can MVP test your prototype. Even if your MVP is still under construction when you set the meeting, whip up something overnight. Has a bank announced a visit to show high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) around the campus? Design a questionnaire for them relating to your project, and make sure you’re the center of attention during the visit. Does a government agency want to see in action some of your university’s technology that holds promise for the future? Engage them in the discussion, and get as much feedback as you can. Don’t resort to simply giving them the old shtick of your academic, top-down presentation, leaving them with nothing to act on after the visit. Engage them wherever you can. Collect their business cards, ask for referrals to other agencies, and ask for one-on-one sessions to gain a better understanding of their problems. You will learn invaluable lessons this way.

All this may sound grossly opportunistic and slightly crazy. It is not, when you begin thinking like a startup entrepreneur who has to make do with whatever presents itself. You will learn that you can be quite aggressive with your ideas and questions before anyone turns you down. As a startup entrepreneur, the world is your MVP testing lab.

The One-Page Proposal

A more formal approach to engaging people with actionable next steps is the one-page proposal, as described by author Patrick Riley.1 It spells out a target or goal, background information about your request, financial details, status quo, and next actions. Thinking in terms of one-page proposals is a helpful exercise to approach business with others. If you know exactly what you want, you can test how serious the other party is about collaborating with you. It is in your interest as an entrepreneur to find those who can help you get your venture off the ground and avoid wasting time with those who cannot or will not.

Here are the individual elements of the one-page proposal:

· Title

· Target

· Secondary targets

· Rationale (the pitch)

· Financial

· Status

· Action

· Name and date

Let’s go through each of them, one by one.

Title

Obviously, this is what your proposal is about. Make sure the title fits on one line. Make it bold, a few points bigger than the other type. “Proposal of XYZ for [company] to investigate potential for joint venture” is a workable title.

Target

The target is what you want—the outcome of what you propose. For example, “Merging synergies with XYZ, complementing product line Z, establishing cost leadership in market X”.

Secondary Targets

These are other effects of the outcome you propose: increasing market share over competitors, a first-of-its-kind project or product, opening the door to a new customer group, and so on. List three secondary targets in bullet form.

Rationale

This section is slightly longer—one or two paragraphs. It outlines your background, some history, how you got started, what you are seeking to do, and some biographical information about the founders and their expertise.

Financial

If you ask for money, or if any other cost is involved (for example, to put on a special event or conference), list what you need. You can also break down the cost of components or anything else that may be relevant to finances in the proposal.

Status

Describe the project’s status quo. For instance, “The concept phase of project X is complete, and the project is ready to go. Prototype X is 80% complete and expected to be ready for testing next week”.

Action

This is the call to action to the other party. For example, “For company XYZ to internally discuss possibilities of a joint venture, then to schedule a follow-up meeting for clarification and questions about the road ahead.”

Name and Date

Print the proposal, and sign and date it at the bottom. This is important and introduces some urgency. All your contact data, including e-mail and phone numbers, goes in the footer of the page.

An Example Proposal

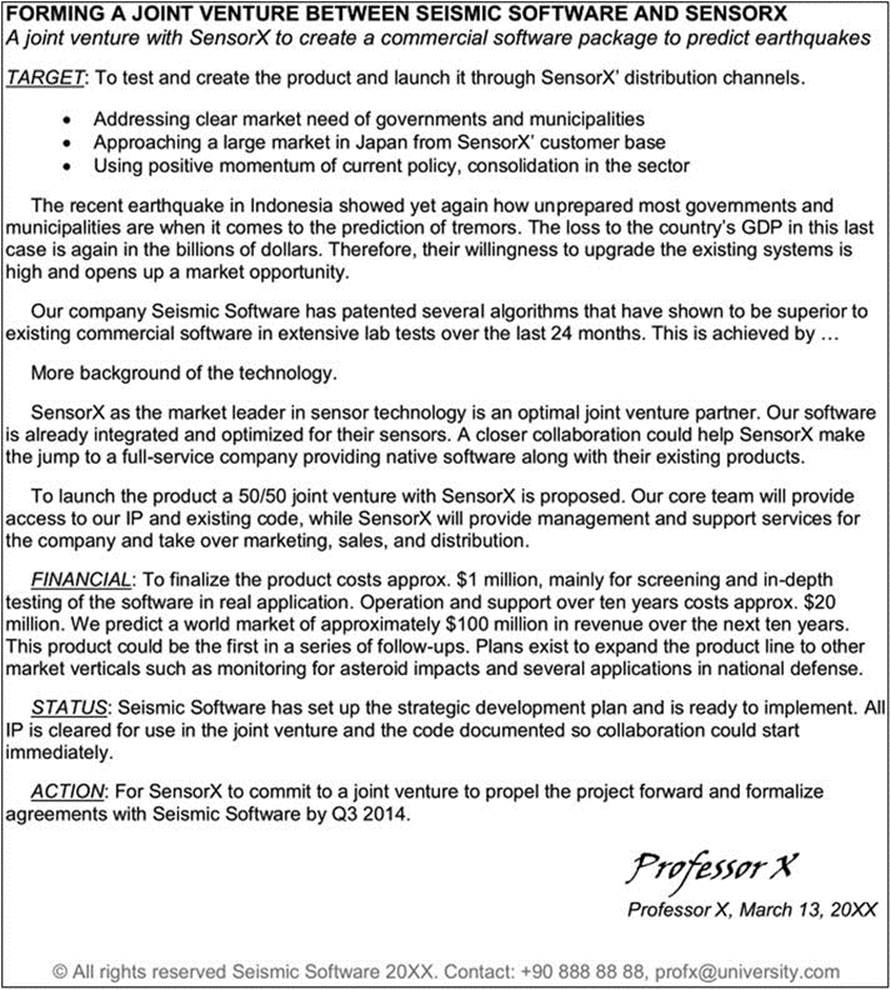

This may all sound abstract. To clarify, Figure 4-1 shows a sample proposal by a fictitious research startup for a joint venture.

Figure 4-1. Sample of a one-page proposal

In general, proposals are more convincing when you deliver them in person instead of via e-mail. Make an appointment, and say that you would like to schedule a meeting to talk about a proposal for a project. Then go to the appointment and take the printed proposal with you, neatly stored in a clear folder. If the recipient insists that you send it, or if they are located in another country, still steer clear of sending a pdf via e-mail. Print it on good paper stock, sign it, and send it to the company via FedEx, addressed to the office of the CEO. This is too significant to be sitting in an e-mail inbox, next to unimportant spam. Make your proposals special.

It may look short and simple, but such a document can take a week to complete. Remember that this is a one-pager, not a one-and-a-half pager. Keep it to one page not only because it is more accessible and elegant, but also because it forces you to strip all the bulk from your presentation and express it concisely. The font size should be at least 10 or 11, and the page should not look cramped.

Getting used to asking directly what you want takes a little while. At first sight it often seems too straightforward, especially to those in academia, where interactions are informal but hesitant. In business, people appreciate your getting to the point and putting your cards on the table. Working with written, actionable proposals shows that you are sincere in your undertaking. Even when you meet potential partners informally, you will sharpen your thinking toward engaging them in your process, rather than just providing entertainment or a good show in the lab.

Prepare a few proposals for mundane things, as practice. Perhaps even write one for the managing director of the university where you conduct your research, proposing certain actions to help you with your startup. Get into the habit of presenting the proposal, and learn as you go.

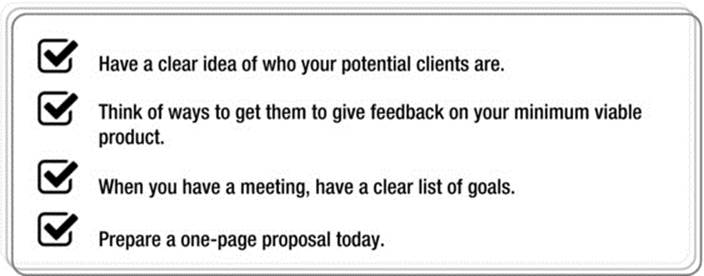

To begin engaging others with actionable next steps, use the checklist in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-2. Checklist for actionable next steps

____________________

1Patrick Riley, The One-Page Proposal: How to Get Your Business Pitch onto One Persuasive Page (New York: HarperBusiness, 2002).