Tax Insight: For Tax Year 2014 and Beyond, 3rd ed. Edition (2015)

Part II. Ordinary Income

Chapter 9. Tax-Free “Unordinary” Income from Non-Investment Sources

What Name Do We Give It?

There are several sources of income that don’t fit nicely into a particular category, such as employment income, investment income, or business income. These sources don’t really even fit into the “other ordinary income” category, in large part because these sources of income are often tax-free and don’t come as a result of normal income-generating activities. Thus I group all of these sources into one chapter and called them “unordinary” income. Included in this newly named category are:

· Workers’ Compensation

· Disability income

· Gifts and inheritance

· Scholarships and grants

· Insurance proceeds

· Lawsuit proceeds

The first two items on the list, Workers’ Compensation and Disability Income, are pretty simple. In nearly all cases the entire amount of income received from these sources is tax-free. The last four items on the list, however, have nuances and stipulations to the “tax-free” title that they bear, and so I focus on these four sources for the remainder of this chapter.

Gifts and Inheritance

When you receive a gift or an inheritance you do not need to worry about being taxed. If the value of a gift or inheritance is large enough to trigger a tax, the tax is levied on the giver (or the estate of the deceased) and not on the receiver. Each year I have clients call to find out how much they will owe on money that they have inherited. The answer is always the same—they owe nothing.

![]() Caution There is one important exception to this rule. If the administrator or trustee of an estate distributes the assets of the estate to the heirs before paying the IRS any gift or estate tax owed, the IRS does have the right to get the money back from the heirs. This is not a tax on the receiver as much as it is a recovery of money from the estate that belongs to the government and was improperly distributed.

Caution There is one important exception to this rule. If the administrator or trustee of an estate distributes the assets of the estate to the heirs before paying the IRS any gift or estate tax owed, the IRS does have the right to get the money back from the heirs. This is not a tax on the receiver as much as it is a recovery of money from the estate that belongs to the government and was improperly distributed.

However, taxes do eventually come into the picture for the receiver. When the person who received the gift or inheritance sells part, or all, of the gift, then the sale of the asset becomes subject to tax. There are interesting rules that govern the sale of gifted and inherited assets.

Gifts

When a person receives a gift, the asset generally retains the giver’s cost basis. “Cost basis” in its most basic form is what a person paid for an item. Cost basis is what determines the taxable gain (or loss) on the sale of an asset—the difference between the cost and the sale price is the gain (or loss).

![]() Example Sylvester bought a work of art for $1,000 in celebration of his daughter’s birth. His cost basis is $1,000. Later, Sylvester gave his daughter the artwork as a present when she turned 18. Even though the art is now worth much more than the original $1,000 that he paid for it, his daughter’s cost basis for the art is still $1,000. If she were to sell it later for $10,000 she would have a $9,000 taxable gain on the sale of the art ($10,000 sale price – $1,000 cost basis = $9,000 taxable gain).

Example Sylvester bought a work of art for $1,000 in celebration of his daughter’s birth. His cost basis is $1,000. Later, Sylvester gave his daughter the artwork as a present when she turned 18. Even though the art is now worth much more than the original $1,000 that he paid for it, his daughter’s cost basis for the art is still $1,000. If she were to sell it later for $10,000 she would have a $9,000 taxable gain on the sale of the art ($10,000 sale price – $1,000 cost basis = $9,000 taxable gain).

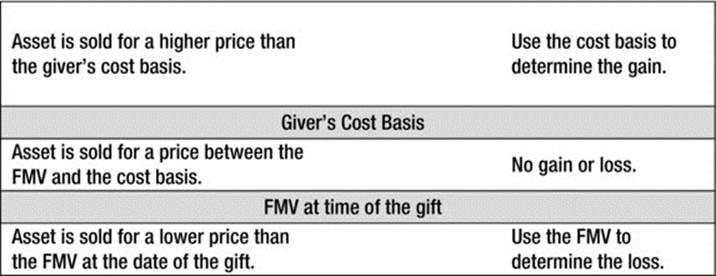

There is one important exception to this rule. If the fair market value (FMV) of the gift is lower than the cost basis at the time of the gift, a new set of rules kicks in when the asset is later sold. The rule that determines the gain or loss is based on the amount for which the asset was sold. If the asset was sold for less than the FMV at the date of the gift, the cost basis used to determine the loss is the FMV at the date of the gift. If the asset is sold for more than the original giver’s cost basis, then the cost basis that determines the gain is the original giver’s cost basis. If the asset is sold somewhere between the FMV at the date of the gift and the original giver’s cost basis, then no gain or loss is recognized. Study Figure 9-1 for a visual illustration of this concept:

Figure 9-1. The sale price, in comparison to the giver’s cost basis and the FMV at the date of the gift, determines whether there is a gain or loss on the sale

![]() Example If the artwork that Sylvester had given his daughter was worth only $500 at the time of the gift, a new set of rules would kick in because the FMV is less than his $1,000 cost basis in the gift. If she later sold the art for $400 she would claim a loss of $100 ($400 sale price – $500 FMV when gifted = $100 loss). If, on the other hand, she sold the art for $1,500 she would have a $500 gain on the sale ($1,500 sale price – $1,000 cost basis of giver = $500 gain). Finally, if she sold the art for $700 there would be no gain or loss because the sale price was higher than the FMV but lower than the cost basis.

Example If the artwork that Sylvester had given his daughter was worth only $500 at the time of the gift, a new set of rules would kick in because the FMV is less than his $1,000 cost basis in the gift. If she later sold the art for $400 she would claim a loss of $100 ($400 sale price – $500 FMV when gifted = $100 loss). If, on the other hand, she sold the art for $1,500 she would have a $500 gain on the sale ($1,500 sale price – $1,000 cost basis of giver = $500 gain). Finally, if she sold the art for $700 there would be no gain or loss because the sale price was higher than the FMV but lower than the cost basis.

The holding period for the recipient of the gift (to determine whether the sale constitutes long- or short-term gains) is the same as the holding period of the giver. The only exception to this is if the FMV of the gift is lower than the giver’s cost basis and the sale price is lower than the FMV was on the date of the gift, in which case the holding period starts on the date of the gift.

Inherited Assets

In general, the cost basis for an asset that you inherit is the FMV of that asset on the date that the decedent died. That basis could be higher or lower than the original owner’s cost basis—whatever it is on the date of death is the new basis for the new owner.

In addition to the new cost basis, the new owner is also given an automatically assumed long-term holding period for the asset. Even if the decedent bought the asset a week before dying, and the new owner sold it a week after the decedent’s death, the holding period is considered long-term and, as such, is given the benefit of long-term capital gains rates.

![]() Caution The rules governing the basis for inherited assets from people who died in 2010 were very different. If you inherited assets from an individual who died in 2010, be sure to check with the preparer of the estate return to ensure that you have the correct basis of those assets.

Caution The rules governing the basis for inherited assets from people who died in 2010 were very different. If you inherited assets from an individual who died in 2010, be sure to check with the preparer of the estate return to ensure that you have the correct basis of those assets.

![]() Note Inherited assets are different than income from estate or trust. Income that is distributed from an estate or trust is taxable to the beneficiary as if it were his or her own income.

Note Inherited assets are different than income from estate or trust. Income that is distributed from an estate or trust is taxable to the beneficiary as if it were his or her own income.

Scholarships and Grants

Scholarships, grants, and fellowships are tax-free to the extent that they pay for tuition, fees, books, and supplies. Amounts given for room and board are taxable and treated as income.

In addition, these funds cannot be given based on services that the student provides to the institution—in other words, they cannot be given in place of wages for services performed. Graduate assistants who receive a reduction in tuition are taxed on that reduction if it is their only compensation, but not if it is in addition to other taxable compensation (such as wages).

Finally, these benefits are tax-free only if the student is actively seeking a degree. There is no pretending that an employee is an eternal student in order to compensate him or her with tax-free income.

Insurance Proceeds

Most insurance proceeds are tax-free. The reason for this is that the money that comes from insurance is seen not as income, but as a replacement for something that was lost.

Life insurance proceeds are usually not taxable. In nearly all cases the money paid from an insurance policy goes to the beneficiary free of tax. However, there are two exceptions to this rule. The first exception is if the deceased person’s estate (including the insurance) is large enough to be subject to the estate tax, in which case the insurance proceeds will be taxed as part of the estate (even worse than income tax). The second exception is if the life insurance policy owner is a business, and the business has deducted the insurance premiums as an expense, in which case the proceeds are considered income.

![]() Tip There are two ways to keep the proceeds of your life insurance policy from being included in your estate. The first is to create an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT). You cannot be the trustee of the trust, but through the language of the trust and the choice of trustee you will be able to control the end results of where and how the insurance proceeds are distributed.

Tip There are two ways to keep the proceeds of your life insurance policy from being included in your estate. The first is to create an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT). You cannot be the trustee of the trust, but through the language of the trust and the choice of trustee you will be able to control the end results of where and how the insurance proceeds are distributed.

The second way to keep life insurance proceeds out of your estate is to have a person other than yourself be the owner. Once you do so you will no longer have control over important things relating to the insurance (such as naming beneficiaries and paying premiums), so there is some risk involved in this decision. However, if there is a person whom you can trust to be the owner and follow through on your wishes, this will allow you to get the insurance out of your estate. In addition, you can give the owner a gift of the money needed for the premiums without tax implications, as long as the amount is less than the annual gift tax exclusion for the year.

There are fairly complicated rules that come into play when you receive insurance proceeds for a damaged or destroyed asset that is a business asset, or that has been depreciated. If this occurs, it is worth taking your situation to a tax professional to ensure that you treat those insurance proceeds the proper way.

Lawsuit Proceeds

Court awards and damages received can be taxable or tax-free, depending on their nature. The best way to determine whether the money received is taxable is to consider what the proceeds are intended to replace. If the money is meant to replace income or wages then it is taxable (just as the income or wages would have been). Other taxable proceeds include punitive damages, attorney’s fees, and damages related to a business or pension.

Proceeds awarded pursuant to a court hearing for a personal injury or sickness are not taxable. This would include damages for emotional distress that is a result of physical injury or illness. However, damages for emotional distress not caused by a physical injury or sickness—such as emotional distress caused by discrimination—are taxable.