Tax Insight: For Tax Year 2014 and Beyond, 3rd ed. Edition (2015)

Part IV. Business Income and Deductions

Chapter 22. Depreciation

Very Complex Tax Rules Boiled Down into Fairly Simple Terms

The rules governing depreciation are very complex, complicated, and convoluted. To give you an idea of how complex they really are, one of the premier guides on depreciation written for tax professionals, the U.S. Master Depreciation Guide, by CCH, is more than 1,000 pages long! Because of the vast number of details and nuances regarding depreciation, I am not going to attempt to give you 1,000 pages worth of information summed up into a 10-page chapter. Instead, this chapter will help you understand the general concept of depreciation and then focus on three key things that you will need to understand as you pursue your tax strategy. The subjects covered in this chapter will be:

· What depreciation is and how it works

· Bonus depreciation

· The Section 179 Deduction

· What happens when you sell a depreciated item

What Depreciation Is and How It Works

My hope in this section is to give you an overarching idea of how depreciation works in the tax code. I will try to make it as simple and general as possible, but that still may not be enough. If you begin to go cross-eyed or feel like your brain is going to burst, just skip to the remaining three sections of this chapter. They are very important for you to understand and I don’t want you to just give up on this chapter before you even get to them. With that said, let’s begin.

There is a general principle in accounting that states that expenses and income should be recognized in the year in which they bring benefit to the business. For example, if you rented a warehouse for a five-year period, but decided to pay the entire rent the day you moved in, this principle dictates that you should recognize only one year’s worth of rent each year for five years (even though the entire amount was paid in one year). The reason for this treatment is that the true benefit of the total expense is enjoyed over five years, and so it is a more accurate reflection of what is really happening in the business to spread the recognition of the expenses over the period of time that is benefited, regardless of the actual cash outflow that occurred, in order to match the expenses with the income that is generated over that same period.

You will find that, most of the time, the tax code follows this principle. To be more accurate, tax laws almost always follow this principle when it benefits the government to do so, and the laws stray from the principle when doing so brings in tax revenue at a more rapid pace. Depreciation is one example of the tax laws following this general principle.

Anytime you purchase an item for your business that has lasting value (of more than a year), that item is most likely subject to the rules of depreciation. Examples of such things are computers, vehicles, furniture, and equipment. If you buy a truck, for example, you would expect it to benefit your business for several years, and so does the IRS.

Every item that you might buy falls under a predefined category for its expected lifespan. All of the items within a certain range of expected lifespans are then assigned a set number of years over which the depreciation should be taken (in other words, a set number of years over which the expense can be recognized). For example, all assets with an expected useful lifetime between four and nine years will be depreciated over a five-year period. Some of the items that fall in this category are cars, most trucks, technology equipment, and office machinery. If you purchased a computer for $1,000 you would recognize one fifth of that cost ($200) each year for five years (assuming a basic, “straight-line” depreciation method is used).

To keep accountants and attorneys in business, Congress has made the depreciation methods a little more complicated than the preceding scenario. The tax code does not simply divide the cost evenly over the stated number of years. Instead, it uses an “accelerated” method of depreciation.

An example of accelerated depreciation is the 200% declining balance method. In this method, 200% of one year’s portion of depreciation is taken each year, based on the value of the item that has yet to be depreciated. For example, if you purchased a $1,000 computer it would be depreciated over five years. Under the simple version of depreciation you would recognize one-fifth of the cost each year, or $200. Under the accelerated method you would recognize 200% of that amount in the first year, or $400. The next year you would divide the remaining un-depreciated balance, or $600 ($1,000 original cost – $400 first-year depreciation = $600 remaining un-depreciated) by the number of years left in the asset’s lifetime—in this case four years (5-year depreciation – the first year = 4 years remaining). The $600 remaining value divided by the four years remaining equals $150 per year. Then, 200% of the year’s amount is taken, or $300. This process continues until the entire value of the asset has been depreciated to $0.

The tax law then adds in one more wrinkle, just to make it interesting. With the accelerated depreciation method you do not actually deduct a full year’s worth of depreciation in the first year. Depending on the type of item that you purchase and the overall timing of all of your purchases during the year, you may need to deduct one-half of the yearly amount, or another amount based on the month or quarter in which it is purchased.

If the computer used in the example above were depreciated using the half-year method of accelerated depreciation, the first year’s depreciation would actually be $200 (200% value was $400, then divided in half for the half-year method). Because of this, the second year would actually be $320 ($1,000 cost – $200 = $800 remaining, $800 × 20% = $160 depreciation × 200% = $320).

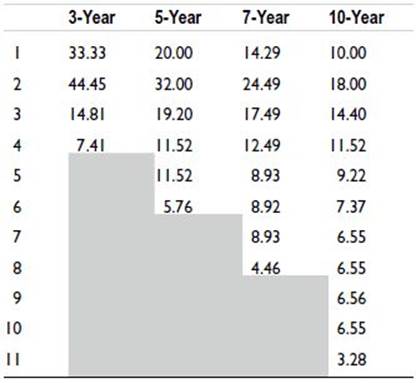

The IRS has published official charts that show the amount of the original cost that should be depreciated each year. As an example I have included one of these charts, Table 22-1 below, which shows the depreciation that should be taken on 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-year items under the half-year convention of the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery (MACRS) system of depreciation that is commonly used on a tax return.

Table 22-1. Depreciation Table for 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-Year Recovery Periods—Half-Year Convention

The take-away from all of this is that many things that you purchase in your business will have to be depreciated, meaning that you will not be allowed to use the full cost of the item as an expense against your income in the year you buy it. It is important to know this because it can dramatically affect your expected taxable income. Based on the item you bought, and the timing of your purchase, varying amounts will be deducted each year until the full cost of the item has been recovered.

However, there are two opportunities within the tax code for you to take a much larger portion of that expense as a current-year deduction: bonus depreciation and the Section 179 deduction. Each of these is described in detail in the following two sections of this chapter.

Bonus Depreciation

Bonus depreciation is a measure that Congress will use occasionally as a way to stimulate the economy by encouraging businesses to buy assets in the current year that they may have otherwise waited to purchase. Bonus depreciation allows business owners to depreciate a significant portion of the purchased price of an asset in the year they buy it, instead of spreading the cost out over many years. In 2013, the tax code allowed for 50% bonus depreciation, which means that 50% of the cost of the asset is depreciated in the first year and the remaining 50% will be subject to the normal depreciation schedules. It is very likely that this provision will be extended into 2014 and 2015, but as of the publication deadline for this book, the law has yet to be passed. Check with your tax advisor or online to verify whether it is available in 2014 and beyond.

There is no limit on the total dollar amount of assets that can receive this special treatment. The assets must be tangible but have a normal depreciable life of 20 years or less, or be computer software (an exception to the “tangible” rule). The asset must also be new (the buyer is the first to use it), and it must be purchased and placed in service by the last day of the year.

To receive bonus depreciation, the asset must be used primarily (more than 50%) for business purposes. If a portion of its use is for non-business purposes then only the pro-rated ratio of business use can be deducted. For example, an item that costs $1,000 and is used 75% for business purposes can receive only a $375 bonus depreciation ($1,000 × 75% business use = $750 is depreciable, $750 depreciable × 50% = $375 bonus depreciation). If during the lifetime of the asset its business use ever drops below 50%, a portion of the asset’s value will be recaptured and treated as income in that year.

![]() Tip Bonus depreciation is often allowed during difficult economic times. However, during these same times many businesses are not very profitable. If your business is in a slump but you expect it to improve in the future, it may be wise to elect out of bonus depreciation. If your income is low, then your tax bracket is low also, which means that the bonus depreciation may not bring much benefit. If you choose normal depreciation methods instead there will be larger amounts of depreciation available from those items to offset income in years when you are in a higher tax bracket.

Tip Bonus depreciation is often allowed during difficult economic times. However, during these same times many businesses are not very profitable. If your business is in a slump but you expect it to improve in the future, it may be wise to elect out of bonus depreciation. If your income is low, then your tax bracket is low also, which means that the bonus depreciation may not bring much benefit. If you choose normal depreciation methods instead there will be larger amounts of depreciation available from those items to offset income in years when you are in a higher tax bracket.

The Section 179 Deduction

There is a provision in the tax code that allows businesses to treat certain assets to be expensed in the year they are purchased instead of requiring them to be depreciated over time. This provision is commonly known as a Section 179 Deduction (so named because it is found in Section 179 of the Internal Revenue Code—accountants aren’t very creative with such things). It can make a very significant difference on your tax liability in a given year if you make a large purchase and can write the entire amount off in that year, rather than depreciating the item over a number of years.

Of course, there are certain limitations attached to the use of this deduction. First, it could be used only by individuals and business entities (not estates or trusts, or certain lessors). Second, in 2013 it can only be used for up to $500,000 of assets purchased during the year. Any additional assets must be subjected to the other depreciation rules. Third, the Section 179 Deduction can be used only if you have purchased less than $2,000,000 of new assets during the year. If you have exceeded that limit the amount of assets that can be expensed is reduced, dollar for dollar, by the amount that your purchases exceeded $2,000,000. If you have purchased more than $2,500,000 then you would not be able to use the deduction and all assets would fall under regular depreciation guidelines. As of the publication deadline of this book the Section 179 Deduction limits have been reduced dramatically in 2014 to $25,000 of assets being deducted and $200,000 of total equipment purchased. However, it is very likely that Congress will retroactively reinstate the higher 2013 limits for 2014 and 2015 by the end of the year.

![]() Example Vince purchased $2,040,000 in new equipment for his construction company during the year. Vince would be able to use the Section 179 Deduction for $1,960,000 of that equipment because the total equipment purchase of $2,040,000 exceeded the purchase limit of $2,000,000 by $40,000. That $40,000 excess in purchases reduces the $2,000,000 maximum 179 Deduction dollar for dollar, making Vince’s maximum available deduction $1,960,000 ($2,000,000 max deduction – $40,000 over spending limit = $1,960,000 available deduction for Vince).

Example Vince purchased $2,040,000 in new equipment for his construction company during the year. Vince would be able to use the Section 179 Deduction for $1,960,000 of that equipment because the total equipment purchase of $2,040,000 exceeded the purchase limit of $2,000,000 by $40,000. That $40,000 excess in purchases reduces the $2,000,000 maximum 179 Deduction dollar for dollar, making Vince’s maximum available deduction $1,960,000 ($2,000,000 max deduction – $40,000 over spending limit = $1,960,000 available deduction for Vince).

An additional limitation placed on the Section 179 Deduction is that it cannot exceed the total taxable income for the business or individual from all business sources (including employment income) during that tax year. Any additional amount would be carried forward to a future year.

![]() Example Duncan is a software engineer for a startup tech company and receives an annual salary of $80,000. He also runs a side business that offers off-site backup systems for computer data, which nets an annual profit of $20,000. This year Duncan purchased a new set of servers for the side business to expand his capacity for growth in clientele. The new servers cost $120,000. Duncan will be able to use the Section 179 deduction for $100,000 of that expense, but the remaining $20,000 will have to be carried over to future years because the total deduction cannot exceed the combined net income from all of his business and employment income sources [($80,000 salary + $20,000 business income = $100,000 total net income, which would also be the maximum deduction).

Example Duncan is a software engineer for a startup tech company and receives an annual salary of $80,000. He also runs a side business that offers off-site backup systems for computer data, which nets an annual profit of $20,000. This year Duncan purchased a new set of servers for the side business to expand his capacity for growth in clientele. The new servers cost $120,000. Duncan will be able to use the Section 179 deduction for $100,000 of that expense, but the remaining $20,000 will have to be carried over to future years because the total deduction cannot exceed the combined net income from all of his business and employment income sources [($80,000 salary + $20,000 business income = $100,000 total net income, which would also be the maximum deduction).

![]() Tip If your total Section 179 Deduction will be limited to a smaller amount that you spent on asset purchases during the year, take care in deciding which assets to use the deduction for because the normal depreciable life of each asset will affect the overall outcome of your return. For example, if you purchased an asset that requires seven-year depreciation and another that requires three-year depreciation, use the seven-year asset for the 179 Deduction so that you can expense it immediately and the other asset will depreciate fairly quickly as well (three years) so that the total deductions taken in the first and subsequent years will be higher and use up the depreciation faster.

Tip If your total Section 179 Deduction will be limited to a smaller amount that you spent on asset purchases during the year, take care in deciding which assets to use the deduction for because the normal depreciable life of each asset will affect the overall outcome of your return. For example, if you purchased an asset that requires seven-year depreciation and another that requires three-year depreciation, use the seven-year asset for the 179 Deduction so that you can expense it immediately and the other asset will depreciate fairly quickly as well (three years) so that the total deductions taken in the first and subsequent years will be higher and use up the depreciation faster.

To be expensed under the Section 179 rules, the asset must be used primarily (more than 50%) for business purposes. If a portion of its use is for non-business purposes then only the pro-rated ratio of business use can be deducted (e.g., an item that costs $1,000 and is used 75% for business purposes can receive only a $750 Section 179 deduction). If during the lifetime of the asset its business use ever drops below 50%, a portion of the asset’s value will be recaptured and treated as income in that year. If you think there is a likelihood of an asset being used more than 50% for personal reasons it may be best not to use this deduction on the asset.

Nearly every depreciable asset that you would buy for your business is eligible for the Section 179 Deduction. Unlike bonus depreciation, the 179 Deduction is allowed for both new and used assets (bonus depreciation can only be taken for new items). However, to qualify for the deduction, the asset must be tangible (meaning you can touch it) and used in the United States. In addition, there are certain items such as heaters and air conditioners, as well as items purchased for long-term dwelling buildings (such as apartments), that cannot be expensed. There are also special limitations placed on the purchase of vehicles. The specific rules in this regard are too complex for the purposes of this book, but if you will be making a substantial purchase and are counting on this deduction, it would be worthwhile to check with a professional to know whether the item qualifies.

![]() Tip Under current law, the Section 179 Deduction will not allow intangible items, such as software, to be expensed, unless Congress acts to modify the 2014 law to match the way it has been from 2003 through 2013.

Tip Under current law, the Section 179 Deduction will not allow intangible items, such as software, to be expensed, unless Congress acts to modify the 2014 law to match the way it has been from 2003 through 2013.

What Happens When You Sell a Depreciated Item

Every item, or asset, that you purchase has something called a tax basis. The “basis” is a way of tracking the value of the item for tax purposes so that when you sell or dispose of the item it can be determined whether you have done so for a gain or a loss. The basis is nothing more than a running total of all of the money you have actually spent on the item netted against the amount that you have taken as an expense on your tax return.

![]() Example Frank purchased a box trailer for his landscaping business. He paid the dealer $20,000 for the trailer, plus $1,000 in taxes. At that point the tax basis of Frank’s trailer is $21,000—the total amount that he had to spend to buy the trailer.

Example Frank purchased a box trailer for his landscaping business. He paid the dealer $20,000 for the trailer, plus $1,000 in taxes. At that point the tax basis of Frank’s trailer is $21,000—the total amount that he had to spend to buy the trailer.

Frank immediately drove the trailer to a neighboring business where it was outfitted with an array of tool boxes and racks for all of his landscaping equipment. The cost of this upgrade was $4,000, bringing his total cost for the trailer (as well as his tax basis) to $25,000.

At the end of the year, Frank’s accountant reported $5,000 of depreciation on the trailer on his tax return. The new tax basis of the trailer, after taking depreciation, is $20,000 ($25,000 basis – $5,000 depreciation = $20,000 new basis).

When you sell a depreciated asset you will be required to report the net-sales revenue that you received from the asset on your tax return. The sales price is compared to the basis of the asset to determine whether you have sold it for a gain or a loss. If you sell the item for more than its basis, you will have to “recapture” some, or all, of the depreciation that you have taken. The depreciation tables are intended to follow the decline in value of the item as it ages. If you sell the item for more than its depreciated basis it means that it was depreciated more than it should have been (which means that you have paid less tax than you should have because of the excess depreciation). The government wants that tax back, so you must recapture (or give back) the excess depreciation on your return.

![]() Example Soon after Frank purchased the new trailer, he lost one of his biggest clients. Because of the significant decrease in his workload, Frank didn’t need to use the new trailer—the work could be handled comfortably with his other equipment. Frank parked the trailer in his garage so that it would be protected from damage until such time that he needed to use it. After three years, it became apparent to Frank that he was not gaining new clients very quickly and would not need the trailer any time soon. He decided to sell the trailer to raise some much-needed cash.

Example Soon after Frank purchased the new trailer, he lost one of his biggest clients. Because of the significant decrease in his workload, Frank didn’t need to use the new trailer—the work could be handled comfortably with his other equipment. Frank parked the trailer in his garage so that it would be protected from damage until such time that he needed to use it. After three years, it became apparent to Frank that he was not gaining new clients very quickly and would not need the trailer any time soon. He decided to sell the trailer to raise some much-needed cash.

Because the trailer was in near-perfect condition Frank was able to sell it for a pretty good price for a used, customized trailer—$20,000. During the three years that he owned the trailer, Frank’s accountant had reported depreciated (according to the schedules) of $17,800, making the tax basis of the trailer $7,200 ($25,000 original basis – $17,800 depreciation taken = $7,200 remaining basis).

Frank will have to recapture $12,800 of the previous depreciation because of the $20,000 he received on the sale ($20,000 sales price – $7,200 tax basis = $12,800 depreciation recapture).

For non–real estate assets, depreciation recapture is treated as ordinary income (since this was the type of income that was offset when the depreciation was taken). There’s a potential catch in this scenario if the recapture is significant enough to push you into a higher tax bracket. In this case you could actually end up paying more for the recapture than you saved from the depreciation.

The possibility of a large recapture is much greater when you have used the Section 179 Deduction or bonus depreciation. In these cases the asset has likely been depreciated at a much faster rate than the asset has actually gone down in value. Selling an asset within a few years of taking one of these special deductions could result in a significant recapture (and tax) in the year you sell it.

If you actually sell an asset for more than the price you originally paid for it (a true gain), you must first recapture all of the depreciation that you have claimed on the asset, and then any remaining gain is treated as a capital gain and taxed at capital-gains rates. If you sell an asset for less than its tax basis you can claim the difference between the sale price and the basis as a loss.

Real estate that is used in a business (including business use of a home) has one additional recapture rule. For any asset that has been appreciated at accelerated rates you must calculate the difference between straight-line depreciation and the accelerated depreciation. The amount of depreciation that would have been taken under the straight-line method is taxed under its own brackets, with a maximum rate of 25%. The remaining depreciation that was taken is taxed at ordinary rates and any remaining gain falls under the capital-gains rules.

![]() Caution I have spoken with clients who want to avoid the possibility of recapturing depreciation. Often it is because they intend to sell the asset within a few years and would rather forgo the yearly benefit to avoid the big hit from the recapture in the year that they sell. For some this strategy makes even more sense because their overall tax picture receives no benefit from claiming the depreciation (because they already have an overall loss, or they are not allowed to claim it because of the passive loss rules). This is a great idea.

Caution I have spoken with clients who want to avoid the possibility of recapturing depreciation. Often it is because they intend to sell the asset within a few years and would rather forgo the yearly benefit to avoid the big hit from the recapture in the year that they sell. For some this strategy makes even more sense because their overall tax picture receives no benefit from claiming the depreciation (because they already have an overall loss, or they are not allowed to claim it because of the passive loss rules). This is a great idea.

However, the tax laws are heartless when it comes to this strategy. When an asset is sold you must recapture all of the depreciation that you could have claimed, regardless of whether you actually claimed it. So, you might as well claim the depreciation and get what benefit you can from it so that you are not hit with a double-whammy in the end.