Tax Insight: For Tax Year 2014 and Beyond, 3rd ed. Edition (2015)

Part I. The Foundation

Chapter 2. Key Components Defined

A Better Understanding

Now that you are familiar with the tax formula, it is important that you understand how each of the key components works, and how each will affect your tax. This chapter will give you a deeper understanding of the following components:

· Income

· Deductions (Adjustments to Income) and AGI

· Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

· Exemptions

· Taxable Income

· Income Tax, Tax Brackets, and Marginal Rates vs. Effective Rates

· The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT)

· Credits (Non-Refundable)

· Other Taxes

· Credits (Refundable)

Income

My client, Jim, called me on the phone one day and said he would be making about $200,000 more that year than in the previous year. He wanted to know how much he should save for taxes. My answer was, “Somewhere between 0 and 50%.” Now, in reading my response you might think that Jim needed another tax advisor. But what he really needed was to tell me how he was earning that extra income. The tax consequences really could have been anywhere in that range. Once I knew the source of that income, I was able to tell him how much to save.

Taxable income includes nearly all income, from whatever source it is derived. Other than a few types of income that are specifically excluded in the tax code, all other types of income are taxable. However, not all income is equal in the eyes of the law. Some types of income receive beneficial tax rates, some have punitive tax rates, some are not taxed, and some are taxed only in certain circumstances. This varying treatment of how different income sources are taxed is just one reason why a few people love tax planning and the rest avoid it like a plague. Nothing is simple or straightforward in the tax code . . . nothing.

Total gross income is the first key component of the tax formula. Nearly all sources of income (taxable and non-taxable) are reported on your tax return, and all of the taxable sources are added together to arrive at your total gross income. Here is a list of the categories of income sources, each of which has a unique method of taxation:

· Ordinary income

· Tax-exempt income (no tax)

· Preferred income (lower than normal tax rates)

· Deferred income (eventually taxed, but not currently)

· Potentially or partially taxed income (including Social Security)

· Penalized income (higher than normal tax rates)

· Earned and unearned income

· Passive income

Each of these types of income is analyzed in Chapter 3. For now, you should focus on three important points. First, nearly every source of income (or increase in wealth) is taxable. There are very few exceptions to this rule, and even those exceptions do not apply 100% of the time. The purpose of the tax code is to enable the government to take your money. Exceptions and exemptions are counterproductive to the very purpose of the code.

Second, the tax code is used to influence, punish, reward, and guide your decisions. This is the reason that there are so many different ways that income sources are taxed.

Third, it is to your advantage to learn how each type of income is taxed and then use that knowledge to adjust your income sources over time to reduce your taxes. Ultrawealthy individuals often pay taxes at a lower rate than middle-class individuals because they have shifted their sources of income to those that are taxed lightly or not taxed at all. Over time you can do the same.

Deductions (Adjustments to Income) and AGI

AGI is an incredibly important acronym. It stands for Adjusted Gross Income. You’ll find it on the last line of the first page of Form 1040 (see Figure 1-1). It is arguably the most important line on your tax return. It can significantly affect the amount of tax you owe. It can also affect your ability to get loans, tuition assistance, and other types of financial support. Your AGI has a far-reaching effect on your financial life.

Remember where adjustments to income enter into the tax formula:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

To understand AGI, you must first understand the meaning of the word “deduction.” A deduction is an expense the government allows you to subtract from your income before you are taxed. It reduces your taxable income to an amount that is lower than your total income.

![]() Example Ted has a total income of $80,000 from taxable sources. However, he contributed $5,000 to his IRA account, paid $4,500 in alimony, and paid $500 in student loan interest. Because each of these expenses is considered deductible in the tax code, Ted has a total of $10,000 in deductions ($5,000 + 4,500 + 500 = $10,000). Thus Ted’s taxable income will be $10,000 less than his actual income, or $70,000 ($80,000 – 10,000 = $70,000).

Example Ted has a total income of $80,000 from taxable sources. However, he contributed $5,000 to his IRA account, paid $4,500 in alimony, and paid $500 in student loan interest. Because each of these expenses is considered deductible in the tax code, Ted has a total of $10,000 in deductions ($5,000 + 4,500 + 500 = $10,000). Thus Ted’s taxable income will be $10,000 less than his actual income, or $70,000 ($80,000 – 10,000 = $70,000).

Deductions come in two varieties. They can be considered “above-the-line” or “below-the-line” deductions. “The line” refers to the bottom line of the first page of the tax return—your AGI. Above-the-line deductions (or adjustments to income) are subtracted from your total income, directly reducing that income when you arrive at AGI.

AGI is a very important number because it determines your eligibility to utilize below-the-line deductions and credits (discussed in the next section). The tax code limits the availability of many deductions and credits to those who have lower- or middle-income levels. (These limits are referred to as phase-outs.) If your AGI is too high, you can lose the ability to use a deduction or credit. For this reason, above-the-line deductions have a very important place in your tax planning. Some examples of above-the-line deductions include:

· Retirement plan contributions

· Student loan interest

· Tuition and fees

· Health savings account contributions

· Self-employed health insurance premiums

· Educator expenses

· Moving expenses

· Alimony

· Self-employment taxes

· Penalties from early withdrawals from savings

Understanding the portion of the tax formula that determines your AGI may be the most important thing that you can do to reduce your total tax liability.

Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

Once you have calculated your AGI it is time to turn to page 2 of your tax return (see Figure 1-1b) in order to complete the remaining items in the tax formula. The next piece of the tax return contains the below-the-line deductions. Here is the formula to this point:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

Just as with the above-the-line deductions, below-the-line deductions reduce your total taxable income. However, your ability to claim the below-the-line deductions may be limited or eliminated by your AGI.

When determining your below-the-line deductions you are given two options. The first option is to use the standard deduction. The standard deduction is a fixed dollar amount, adjusted for inflation by the IRS each year, that a taxpayer can claim regardless of his or her actual expenses. It is not based on any real deductible expenses incurred during the year. Rather, it is based on your filing status (single, married filing jointly, head of household, etc.). You can always choose to claim the standard deduction, regardless of what your true itemized deductions add up to (except for special rules applying to those who are married and filing separately).

As an alternative to the standard deduction, you may add together all of your actual deductible expenses, known as “itemized” deductions. If the sum of itemized deductions is higher than the standard deduction, you will usually achieve a better tax result by itemizing.

Expenses eligible to be claimed as itemized deductions are familiar to most taxpayers. Some of the more common ones are:

· Medical expenses

· Mortgage interest (and certain other interest)

· State income and sales taxes

· Property taxes

· Charitable contributions

· Employee expenses (not reimbursed)

· Investment expenses

· Tax preparation fees

Nearly all of the itemized deductions have limitations placed on them based on your AGI. For example, you only can deduct medical expenses that are greater than 10% of your AGI (or greater than 7.5% if you are over age 65 and not subject to the Alternative Minimum Tax). The list of reductions and limitations on itemized deductions is long, but each can serve to reduce or eliminate the benefit of the deductible expenses.

It is also important to understand that itemized deductions will do you no good if they do not add up to more than the Standard Deduction (after they have been reduced by the AGI limitations). It is not uncommon for a client to have a sudden increase in his itemized deductions, such as a large medical expense or a new mortgage, and then be confused because it did not make a difference in his taxes or even show up on his tax return. All of the deductions must be subjected to their AGI limitations and then still add up to more than the Standard Deduction in order to be of any benefit to your taxes. Don’t be caught spending money on “deductible” expenses, only to realize that you won’t be able to deduct them. (In contrast, the usefulness of above-the-line deductions is not affected by the standard deduction.)

Deductions cannot reduce your taxable income below zero. Put another way, if all of your deductions add up to more than your taxable income, any additional deductions will do you no good. The benefits of those deductions are lost when you have no corresponding taxable income to reduce.

Exemptions

Generally, each taxpayer is allowed to reduce his or her taxable income by an additional amount known as an exemption. An exemption is a fixed dollar amount, adjusted for inflation, that a taxpayer can claim as a reduction to his or her taxable income in addition to the standard or itemized deductions. Here is a look at the placement of exemptions in the tax formula:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

The theoretical reasoning for the exemption is to protect a minimal amount of income from taxes, approximately the amount that is needed to cover the most basic of life’s necessities, such as food. In addition to claiming a personal exemption, each person is also allowed to claim an additional exemption for every individual who qualifies as a dependent, since the costs of those basic necessities increase with each dependent.

![]() Example Mike and Julie are married and have three young children who qualify as their dependents. Mike and Julie can claim five exemptions on their tax return (one for Mike, one for Julie, and one for each of their three dependent children). If the individual exemption amount happened to be $4,000 in a given year, Mike and Julie could claim $20,000 in exemptions as a reduction to their taxable income for that year (5 exemptions x $4,000 each = $20,000).

Example Mike and Julie are married and have three young children who qualify as their dependents. Mike and Julie can claim five exemptions on their tax return (one for Mike, one for Julie, and one for each of their three dependent children). If the individual exemption amount happened to be $4,000 in a given year, Mike and Julie could claim $20,000 in exemptions as a reduction to their taxable income for that year (5 exemptions x $4,000 each = $20,000).

These exemptions help to reduce taxable income further. Beginning in 2013, exemptions are reduced or eliminated for taxpayers with a high AGI. The rules regarding personal and dependency exemptions and specific dollar amounts are discussed in detail in Chapter 4.

Taxable Income

Once you have determined the proper amounts to report for AGI, deductions, and exemptions, you are able to complete the most significant portion of the tax formula:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

= Taxable Income

After reducing your total income by claiming all allowable adjustments, deductions, and exemptions, you arrive at your taxable income. Taxable income is the amount of your income that is actually subjected to the income tax. It is also the figure that determines your marginal tax bracket (the tax rate at which your next dollar of income is taxed).

Income Tax, Tax Brackets, and Marginal Rates vs. Effective Tax Rates

The next step in the tax formula is to determine your initial income tax liability, based on the rates in the income tax brackets:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

= Taxable Income

× Tax Rates

= Income Tax (or AMT)

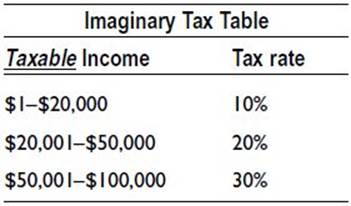

Our income tax system is progressive, which means that as your taxable income increases, the increased amounts are taxed at increasing rates. Your total income is broken into pieces and each group, or segment of that income, is taxed at a different rate. For the sake of simplicity, let’s imagine that the tax bracket tables look like this:

In this scenario, if Mary had a taxable income of $60,000 during the year, she would have an income tax obligation of $11,000. This is so because the first $20,000 of her taxable income is taxed at a rate of 10%, or a $2,000 tax ($20,000 x 10% = $2,000). The next $30,000 of her taxable income (the income between $20,001 and $50,000) will be taxed at a 20% rate, or a $6,000 tax ($30,000 x 20% = $6,000). The remaining $10,000 of her taxable income (the amount over $50,000) will be taxed at a rate of 30%, or a $3,000 tax. Adding each of those taxes together ($2,000 + $6,000 + $3,000) brings us to a total tax of $11,000.

This illustration brings us to another important distinction: the difference between marginal and effective tax rates. When you hear a person say something like, “I am in the 25% tax bracket,” what they are referring to is their marginal tax rate. Your marginal rate is the amount of tax that you pay on your last dollar earned. In the illustration above, Mary’s marginal tax rate is 30%, because that is the rate that she paid on her last portion of income. Had she stopped earning money $10,000 sooner, she would have had a lower marginal rate (20%).

On the other hand, Mary’s effective tax rate is 18.33% (as compared to her marginal tax rate of 30%). The effective tax rate is the average rate that you pay on all of your income combined. While Mary paid 30% on the last part of her income, she also paid 10% on a different portion of it and 20% on another part of it. When taken as a whole, her effective rate would be 18.33% ($11,000 tax/$60,000 taxable income = 18.33%).

![]() Note There is one more way to look at the true tax rate that Mary paid. Marginal and effective tax rates are both based on taxable income. Mary actually had a gross income of $88,000, but $10,000 of that income came from non-taxable sources and she had $18,000 in deductions and exemptions ($88,000 gross income – $10,000 non-taxable income – $18,000 deductions and exemptions = $60,000 taxable income). If you look at the amount of tax that Mary paid as a percentage of her gross income, it would be only 12.5% ($11,000 tax $88,000 gross income = 12.5%). So, Mary’s marginal tax rate is 30%, her effective tax rate is 18.33% and her tax as a percentage of her gross income is 12.5%.

Note There is one more way to look at the true tax rate that Mary paid. Marginal and effective tax rates are both based on taxable income. Mary actually had a gross income of $88,000, but $10,000 of that income came from non-taxable sources and she had $18,000 in deductions and exemptions ($88,000 gross income – $10,000 non-taxable income – $18,000 deductions and exemptions = $60,000 taxable income). If you look at the amount of tax that Mary paid as a percentage of her gross income, it would be only 12.5% ($11,000 tax $88,000 gross income = 12.5%). So, Mary’s marginal tax rate is 30%, her effective tax rate is 18.33% and her tax as a percentage of her gross income is 12.5%.

I received a call from a client one day who was trying to decide whether to accept a promotion at work (and the increased income that would come with it). He knew from our previous conversations that he was on the cusp of entering the next tax bracket—a 10% jump from his current one. He was worried that earning extra money because of the promotion would suddenly push him into a new tax bracket and he would be stuck paying 10% more on all of his taxable income.

This, of course, was not the case. If it were, the increased taxes from the higher tax bracket would effectively cancel out his raise or possibly make him worse off than before. What he did not understand was that only the new income would be subject to the higher tax rates. I have found this to be a very common misconception.

The Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT)

Up to this point in the chapter, I imagine everything has been fairly straightforward. You have been able to follow and understand the terminology, principles, and formulas that determine how much tax you must pay. Don’t get caught thinking anything in the tax code is straightforward, though! Remember, nothing is simple or straightforward in the tax code . . . nothing.

A prime example of complication in the tax code is the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). Once you have completed the first portion of the tax formula and have computed your total income tax, the government reserves the right to determine that the income tax you owe is not high enough. To ensure that your tax is at least as high as it “should” be, you may be required to recalculate your tax using a different (or alternative) formula. This alternative formula calculates the tax that you would owe if they were to take away some of your deductions, add in some of your tax-exempt income, and then calculate a tax based on a new (higher) set of tax brackets.

Once you have completed the second formula, you then compare your new tax figure with the original income tax. If the alternative tax is higher than the original tax, you must pay the additional amount. This new, higher tax is appropriately named the Alternative Minimum Tax. You see, there is a minimum amount you should pay, in their eyes, and so you are not allowed to use the standard rules if it results in a tax that is too low.

The AMT is becoming an increasingly important area of tax planning because it is affecting more and more people each year. Many people who are far from “rich” are finding out the hard way that the AMT is a part of their tax formula. It can have a significant financial impact on people with relatively modest incomes. You will find a more in-depth discussion of the AMT and the strategies available to reduce it in Part 7 of this book.

Credits (Non-Refundable)

Now we have arrived at the good stuff. Credits are the biggest, juiciest berries on the bush. If they are available to you (determined by your AGI), they can bring a lot of “bang for your buck.” Here is how non-refundable credits fit into the tax formula:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

= Taxable Income

× Tax Rates

= Income Tax (or AMT)

– Credits (Non-Refundable)

= Cannot equal less than $0 at this point

It is important to understand the difference between a credit and a deduction: they are not one and the same. In fact, they are dramatically different. Deductions reduce your taxable income. That means that your tax savings from a deduction is equal to your marginal tax rate multiplied by the amount of the deduction.

![]() Example If your marginal tax rate is 15%, you will pay $15 in taxes for every additional $100 you earn (until you reach the next tax bracket). Conversely, for every $100 you have in deductions, you will save $15 in taxes. Deductions reduce your taxes proportionate to your tax bracket—so the higher your tax bracket is, the more valuable deductions can be.

Example If your marginal tax rate is 15%, you will pay $15 in taxes for every additional $100 you earn (until you reach the next tax bracket). Conversely, for every $100 you have in deductions, you will save $15 in taxes. Deductions reduce your taxes proportionate to your tax bracket—so the higher your tax bracket is, the more valuable deductions can be.

Credits, on the other hand, reduce your taxes (not taxable income) directly. For every $100 you have in credits, you will save $100 in taxes. Credits reduce your taxes dollar for dollar, whereas deductions reduce your taxes only by the percentage of your marginal tax rate. This gives credits a very important role in your tax formula.

The first credits available on the tax return are non-refundable. In other words, these credits can reduce your tax to $0, but no less (they can’t create a refund greater than the amount of tax you have paid or withheld—hence the term non-refundable). Even though they cannot create a surplus refund, reducing your tax to $0 is still really good. Some of the more common non-refundable credits are:

· Child Tax Credit

· Child and Dependent Care Credit

· Education Credits

· Residential Energy Credits

· Elderly and Disabled Credits

· Foreign Tax Credit

· Retirement Savings Contribution Credit

· Adoption Credit

· Prior Year AMT Credit

· General Business Credits

Understanding which of these credits apply to your situation can make a significant difference in the taxes that you owe.

Other Taxes

In addition to the regular income tax and the Alternative Minimum Tax, there are a few other taxes that enter the picture in the next portion of the formula:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

= Taxable Income

× Tax Rates

= Income Tax (or AMT)

– Credits (Non-Refundable)

= Cannot equal less than $0 at this point

+ Other Taxes

For some people the “other” group of taxes can be more significant than the income tax and AMT. Two factors contribute to this. The first is that these “other” taxes are determined without regard to adjustments, deductions, exemptions, or credits. Therefore, you can’t reduce these additional taxes through traditional methods. Second, these additional taxes do not count toward minimum tax calculation to reduce the gap between the regular and minimum tax. The “other” taxes are in addition to the regular tax and the AMT.

A good illustration of this is in the tax return of a client I’ll call Bob. Bob has an above-average income. He also has a lot of personal expenses that qualify as deductions. In fact, by the time you subtract all of his deductions from his income, Bob has zero taxable income—no tax!

Unfortunately for Bob, however, most of his income comes from owning a business. Even though he has no income tax liability, he is on the hook for an “other” tax—the self-employment tax. The self-employment tax is calculated separately from income taxes, without regard to personal adjustments, deductions, exemptions, or credits. It is a flat 15.3% tax of his net business income. As a result, he pays several thousand dollars in taxes each year that he wouldn’t have owed if his income had come from another source, such as from investments.

Included in the group of “other” taxes are:

· Self-employment tax

· Additional Medicare Tax (from the Affordable Care Act)

· Net Investment Income Tax (from the Affordable Care Act)

· Penalties for early withdrawal of retirement funds

· Taxes on tips

· Taxes on household employees (such as a maid or nanny)

· Repayment of the homebuyer credit

Just when you think you have made it safely through the tax maze and are aware of what you owe, these other taxes can jump out and get you. This is an area of the tax return where careful planning can make a big difference for business owners.

Credits (Refundable)

In the world of taxes, it doesn’t get any better than this. If the “other taxes” section of Form 1040 were to be named the “devil of the tax return,” refundable credits would be the “guardian angel,” ready to save you in the end. If you qualify for these special credits, they will be the best part of your tax return. Here they are, near the end of the calculation:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

= Taxable Income

× Tax Rates

= Income Tax (or AMT)

– Credits (Non-Refundable)

= Cannot equal less than $0 at this point

+ Other Taxes

– Credits (Refundable)

There are two reasons why the refundable credits play such an angelic role. First, these credits come after the “other taxes” section on the tax return. This means that, unlike the non-refundable credits, these credits can reduce your entire tax bill, including penalties and the self-employment tax. Second, these credits are refundable. What this really means is that even if your tax bill is zero, these credits can take your tax bill into negative territory. In other words, these credits can make the government owe you money. Even if you haven’t paid one dime in taxes, you could get a “refund.” These credits are treated the same as if they were “payments” that you had made.

![]() Example After taking into account all of Nancy’s income, adjustments, deductions, exemptions, and non-refundable credits, her tax liability is $0. During the year she had $500 withheld from her paycheck. Nancy also qualifies for $1,000 of Earned Income Credit (a refundable credit). Under normal circumstances, if she owed no taxes she would get a refund of the $500 that was withheld from her paycheck. However, because the Earned Income Credit is refundable, she will also receive an additional $1,000 “refund” because of the credit, for a total refund of $1,500—even though she paid only $500 in taxes during the year!

Example After taking into account all of Nancy’s income, adjustments, deductions, exemptions, and non-refundable credits, her tax liability is $0. During the year she had $500 withheld from her paycheck. Nancy also qualifies for $1,000 of Earned Income Credit (a refundable credit). Under normal circumstances, if she owed no taxes she would get a refund of the $500 that was withheld from her paycheck. However, because the Earned Income Credit is refundable, she will also receive an additional $1,000 “refund” because of the credit, for a total refund of $1,500—even though she paid only $500 in taxes during the year!

I’m not sure that “refund” is the appropriate word for this scenario, but whatever you call it, this is a great tax break for those who qualify. The most common refundable credits are:

· Earned Income Credit

· Additional Child Tax Credit

· American Opportunity Credit

· Adoption Expenses

· Health Coverage Tax Credit

In addition to the credits listed above, there are a few other refundable credits available for taxes that you were required to pay but should not have been. These are:

· Excess Social Security Tax Withheld

· Tax on Fuels (for off-road use)

· Minimum Tax

The old adage of “save the best for last” definitely applies here. The best part of the tax formula comes at the end in the form of refundable credits.

The Calculation Is Complete

As you can see, each section of the tax return plays an integral part in the formula that determines your tax. Understanding each part is the foundation of successful tax planning. The final piece of the formula is to subtract any payments that you have made, which will give you the final determination of whether you owe the government money or they owe you. Here is one last look at the complete formula:

+ Income

– Deductions (Adjustments to Income)

= Adjusted Gross Income (AGI)

– Deductions (Standard or Itemized)

– Exemptions

= Taxable Income

× Tax Rates

= Income Tax (or AMT)

– Credits (Non-Refundable)

= Cannot equal less than76.5 pt $0 at this point

+ Other Taxes

– Credits (Refundable)

– Payments

= Taxes Due or Refund

No longer need you be confused by all of the lingo and jargon of the tax world. No longer should you be intimidated by the complexity of the code. With this solid foundation under your belt, you are more prepared to move forward and take control of one of the biggest and most complex expenses in your life.

![]() Note Be sure to read the remaining chapters in Part 1 before going on to the rest of this book in order to gain a deeper understanding of the different types of income, the effects of filing status, the role of dependency exemptions, and some of ways that the tax code is rigged against you. Once you have a firm grasp of the information presented in Part 1, the remaining chapters and appendices of the book will help you discover strategies you can use within each section of the tax return, as well as recognize what value they may have in your individual circumstances. You will be ready to recognize and harvest the juiciest berries on your unique taxberry bush.

Note Be sure to read the remaining chapters in Part 1 before going on to the rest of this book in order to gain a deeper understanding of the different types of income, the effects of filing status, the role of dependency exemptions, and some of ways that the tax code is rigged against you. Once you have a firm grasp of the information presented in Part 1, the remaining chapters and appendices of the book will help you discover strategies you can use within each section of the tax return, as well as recognize what value they may have in your individual circumstances. You will be ready to recognize and harvest the juiciest berries on your unique taxberry bush.