Tax Insight: For Tax Year 2014 and Beyond, 3rd ed. Edition (2015)

Part I. The Foundation

Chapter 5. The Tax Code Is Rigged

It Enforces, Enhances, and Enshrines the Wealth Gap–but It Can Be Beat

For centuries, economists and social scientists have recognized that people’s actions, no matter how well thought through, have unintended and un-anticipated consequences. At times the unintended consequence is minimal, such as the temperature in a freezer getting temporarily warmer when you place a new item inside of it. At other times the unintended consequence is so significant that instead of bringing a solution to a problem, it actually makes it worse.

![]() Example Mack and Jessica were at a dinner party with several other couples. During the meal, Mack noticed that Jessica had a piece of food on her cheek. Hoping to help her remove the food before others noticed, Mack tried to signal to Jessica that she needed to wipe her face. However, he did it in such a way that all of the other people at the table saw him and then looked at Jessica to see what the matter was. In trying to save her embarrassment and take care of the problem before others noticed, he actually drew attention to it—the opposite of what he intended to do.

Example Mack and Jessica were at a dinner party with several other couples. During the meal, Mack noticed that Jessica had a piece of food on her cheek. Hoping to help her remove the food before others noticed, Mack tried to signal to Jessica that she needed to wipe her face. However, he did it in such a way that all of the other people at the table saw him and then looked at Jessica to see what the matter was. In trying to save her embarrassment and take care of the problem before others noticed, he actually drew attention to it—the opposite of what he intended to do.

The phenomenon I am describing is known as the Law of Unintended Consequences. It is fascinating to learn about it and become aware of the innumerable examples of its occurrence in everyday life. Perhaps nowhere is its existence more apparent than in the acts of government, where continuous efforts are made to control people and the world around them, with limited ability to foresee all of the consequences that will result.

Unintended consequences are pervasive in the tax code. There are dozens of examples. In my mind, the most damaging and misunderstood of these unintended consequences in the tax code is found in the attempts to tailor the tax code to help the poor and extract more from the rich.

![]() Note It can be argued that these consequences are not unintended, but rather they are intentionally placed in the tax code to benefit the rich. In calling them “unintended” I am giving Congress the benefit of the doubt. When the purposes of individual provisions of the tax code are explained, especially at the time they are voted on in Congress, the noblest reasons are given for each law—often based on bringing benefits to the lower and middle class while disallowing these benefits for the rich. Based on these stated reasons, the resulting consequences could only be seen as unintended. However, many people believe that ulterior motives are at work.

Note It can be argued that these consequences are not unintended, but rather they are intentionally placed in the tax code to benefit the rich. In calling them “unintended” I am giving Congress the benefit of the doubt. When the purposes of individual provisions of the tax code are explained, especially at the time they are voted on in Congress, the noblest reasons are given for each law—often based on bringing benefits to the lower and middle class while disallowing these benefits for the rich. Based on these stated reasons, the resulting consequences could only be seen as unintended. However, many people believe that ulterior motives are at work.

Though they may have short-term benefits to those with lower incomes, the very attempts to help those in the lower and middle classes through tax incentives have the opposite effect when those individuals are trying to climb into a higher economic class. At the same time, those same tax rules end up working to the benefit of the truly rich.

These Three Things

This “greatest” of the unintended tax consequences is caused by the combination of three factors of the tax code. Together these three factors form a potent formula to prevent upward movement in economic status:

· Unequal treatment of income (certain types of income being taxed at higher rates than others)

· Progressive tax rates (increasingly higher rates with higher income)

· Phase-outs of deductions and credits (reducing or eliminating tax benefits for those with higher incomes)

While the first of the three factors is not directly intended to help the poor and middle class (its intent is to spur business investment and job growth), the full focus and purpose of the second and third factors is to reduce the tax burden on those with lower incomes and increase it on those with higher incomes—to help the poor and tax the rich. However, the way the tax code is written actually brings about a totally different result.

The problem lies in the fact that our primary taxing system is an income tax, not a wealth tax. Because of that, when we place a higher burden on the “rich” we are actually placing the burden on a higher income. The more your income increases, the greater the burden you bear. The reality, though, is that the truly “rich,” or wealthy, may not have (or need) a high employment income—they can live off of their wealth. What the tax code actually does is make it very hard to accumulate wealth, or move from one economic class to the next. Once you have accumulated wealth, the tax code does not exact any great burden on you—in fact its burden is lifted. It is in getting to that point where the real weight of our tax code is felt. In other words, our tax code is written in a perfect way to keep the lower and middle classes down.

![]()

![]() Illustration Imagine a three-story building. Each story represents a level of wealth: the ground floor is for the poor, the second floor is for the middle-class, and the third floor is for the rich. Each of the floors has an opening between it and the next floor so that a person has the opportunity to move up from the first to the second and, finally, to the third floor. To move from one floor to the next, however, that person must build a stairway out of blocks to climb up to the next floor.

Illustration Imagine a three-story building. Each story represents a level of wealth: the ground floor is for the poor, the second floor is for the middle-class, and the third floor is for the rich. Each of the floors has an opening between it and the next floor so that a person has the opportunity to move up from the first to the second and, finally, to the third floor. To move from one floor to the next, however, that person must build a stairway out of blocks to climb up to the next floor.

On the first floor the government provides several blocks to the poor, free of charge, to help them get started building their staircase. Once a person begins to create additional blocks beyond those that the government offered, however, the government begins to take back the person’s blocks and give them to others in need. The more blocks a person creates on his or her own, the more blocks the government takes away. In fact, the government will even begin to taking away the person’s own blocks once all of the original government blocks have been removed. The person is left working furiously to accumulate blocks at a faster rate than the government takes them away until he or she manages to reach the third floor (if ever).

Once he or she reaches the third floor, however, the rules for that individual change. Once on the third floor it no longer matters if the blocks in your staircase are removed because you are already on the third floor—you don’t need them anymore. In fact, when you are sufficiently rich you can structure your income sources in such a way that they are significantly protected from the government’s ability to take them away, allowing you to maintain your status on the top floor, unscathed by the government’s attack on earned income (the blocks).

This imaginary scenario is a demonstration of what truly happens to people as they encounter the three potent factors of the tax code. Though phase-outs and progressive tax rates may protect the poor and middle class, it is true only as long as the individuals are content to stay poor or middle-class. As soon as they begin to make enough money to move from poor to middle class or from the middle class to rich, those phase-outs and tax rates will kick in and make it very difficult for them to accumulate enough wealth to climb to the next higher class. On the other hand, the different ways in which income sources are taxed works to protect the wealthy from losing their status.

To help you visualize the dramatic effects that these three factors working together can have on a person who is trying to get ahead, I want to walk you through some illustrative specific numbers.

First, assume that the cost of living for a family of four is $100,000 per year. Second, $50,000 of the family’s income is not taxable, due to deductions, exemptions, and credits. Third, all of the income that remains after taxes and living expenses will be put toward savings in order to accumulate wealth. Fourth, we will assume that a family is wealthy once it accumulates $3,000,000 in savings. At that point the family could cover its $100,000 in living expenses by living off of the interest from a tax-free municipal bond earning 3.5% and allowing some of the interest to compound in order to keep up with inflation.

Next, I will apply each of the three factors to this family’s situation, one at a time, in order to see how long it will take them to become wealthy under each circumstance. As the illustration progresses, the compounding effect of this trio will become obvious—as will the reality that the tax code is written very effectively to penalize wealth accumulation.

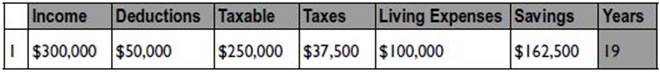

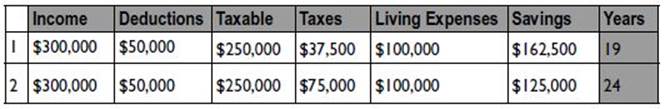

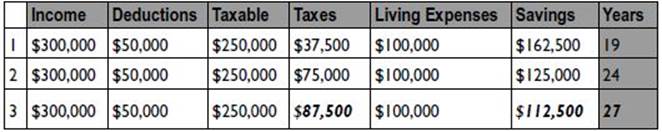

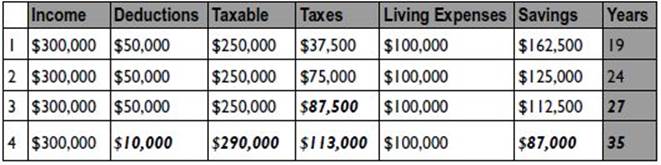

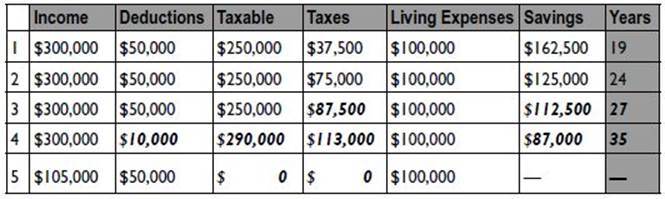

We’ll start with a baseline scenario in which none of the three factors exist. In this scenario a family earns $300,000 per year; has $50,000 in deductions, exemptions, and credits; and spends $100,000 in living expenses. For the baseline, we will assume that there is a 15% flat tax on all types of income and at all income levels. In this scenario the family is left with $162,500 to put toward savings. At this savings rate it would take 19 years for the family to arrive at the goal of $3,000,000. This baseline scenario is illustrated below.

For the second scenario we’ll introduce the first of the three factors: the tax rate is increased by an extra 15% (for a total of 30%), based on the fact that the source of the $300,000 of income is considered “earned” income (which is subject to Medicare and Social Security taxes, or payroll taxes). In this second scenario it would take 24 years to achieve the goal, as illustrated in line 2 below.

Now, in the third scenario we will introduce the progressive tax system, or tax rates that get higher as your taxable income increases. For this illustration we will assume that the family’s tax rate at their income level is 33%, making an effective tax rate of 20% (because the tax is progressive), bringing the total tax (including payroll taxes) to 35%. As you can see on line 3 below, it will now take 27 years for them to achieve their goal of $3,000,000 in savings.

For the fourth scenario we will also include phase-outs on their deductions and credits. We will assume that at an income level of $300,000 the family has 80% of its deductions and credits phased out, allowing only $10,000 in deductions instead of the $50,000 that would have been allowed without the phase-outs. In addition, having fewer deductions increases the taxable income, which in turn increases the amount of income taxed in the highest bracket, bumping the family’s effective tax rate up to 39%. As this third factor compounds with the previous two, it will take the family 35 years to achieve its goal—nearly twice as long as it would have taken in the original scenario and very difficult to achieve by the time the parents reach a normal retirement age (they would need to be earning this high income from an early age).

Now, let’s compare this unfortunate family with a family who has already achieved $3,000,000 of wealth. Because the already-wealthy family has no need for earned income (the members have invested their $3,000,000 in tax-free bonds and are able to cover all of their living expenses from the interest, paying $0 tax), it is not subjected to progressive tax rates or higher rates on earned income. What is more, the family also has $50,000 in deductions that are going unused because its income is from tax-free sources. The members could go out and earn an additional $50,000 without paying any additional income tax because the income would be offset by those unused deductions. They could then put the full $50,000 to work building their wealth even further (virtually free of the burden of taxes). See how the incomes of the two families compare below.

As you can see from this illustration, these three potent factors in the tax code (progressive tax rates, phase-outs, and differences in how income sources are taxed) work together to make it extremely difficult to move from one economic status to a higher one (in this case from middle-class to rich). In similar fashion, those who are trying to move from poor to middle class have many tax credits pulled out from under them, making their progress up the economic ladder difficult as well (as you will see illustrated in the example below about a client named Maggie). The very tools that are used in the tax code to ease the burden on low- and middle-income earners and increase it on high incomes benefit the lower and middle classes only if the individuals stay put. If they attempt to improve their situation they are faced with very stiff headwinds that, for most, won’t ever be overcome.

Phase-Outs: The Devil in Disguise

In Chapter 3 you learned about how different income sources are taxed at different rates, and in Chapter 2 you learned about the progressive structure of the tax code, meaning tax rates become increasingly higher as taxable income increases. However, the third factor in the rigging of the tax code is phase-outs, and it merits a thorough discussion to ensure that you fully understand how they work and their implications.

When Congress creates a tax deduction or credit, it usually limits its availability to a certain group of people (usually to those within a certain range of income). Congress most commonly accomplishes this through a technique known as phase-outs. Though the intent of these phase-outs is clear (and perhaps justifiable), the unintended consequences can sometimes be unbelievable.

![]() Example Suppose that Congress creates a new credit called the “Gas Purchase Assistance Credit (GPAC).” The purpose of this credit is to help low-income workers afford the increasing cost of gas for their vehicles. The credit gives a $1,000 tax refund for the first $2,000 of fuel purchased during the year. However, to keep wealthy individuals from also claiming this credit, Congress stipulates that the GPAC credit be available only to those individuals with an Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) below $35,000. This limitation is called a phase-out.

Example Suppose that Congress creates a new credit called the “Gas Purchase Assistance Credit (GPAC).” The purpose of this credit is to help low-income workers afford the increasing cost of gas for their vehicles. The credit gives a $1,000 tax refund for the first $2,000 of fuel purchased during the year. However, to keep wealthy individuals from also claiming this credit, Congress stipulates that the GPAC credit be available only to those individuals with an Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) below $35,000. This limitation is called a phase-out.

Phase-outs come in three varieties, differing in how quickly or dramatically the phase-out occurs. One variety is an absolute cutoff, as in the preceding example. With the GPAC credit, if your AGI were $34,999 you could receive up to $1,000 in tax credits. If it were $1 higher, you would get nothing. This type of phase-out does not make a lot of sense, is not really equitable, and leads to a great temptation for dishonesty for those who are near the threshold of the cutoff. There is a lot of incentive to fudge the numbers in order to get the credit—$1 more in reported income could cost you $1,000 in taxes. Nevertheless, this type of phase-out is found in several places in the tax code. An awareness of these types of “cutoff” phase-outs in your tax planning can make for a dramatic difference in your taxes.

The second type of phase-out offers more of a smooth transition between receiving and not receiving the benefits of the deduction or credit. If the GPAC example were written to be this type of phase-out, it would reduce the benefit over a range of incomes, such as reducing the available credit by $1 for every $5 of AGI over $35,000. In this way the credit would get smaller and smaller until it disappeared completely at an AGI level of $40,000. This type of phase-out does a much better job at meeting its intended purpose by not making such a dramatic distinction between taxpayers whose incomes may differ by only a few dollars.

The third and least common type of phase-out is a tiered or stepped version. It has distinct cutoff points, but those cutoffs remove only a portion of the deduction or credit available. The GPAC credit under this type of phase-out might look like this: $1,000 credit available for an AGI below $35,000, $500 available for an AGI below $37,500, and $0 available for an AGI above $40,000.

Why does all of this matter?

It matters because, if you are not aware of phase-outs, they can easily take you by surprise on your tax return and they often come with a powerful punch. They must be watched very closely as you engage in tax planning, because they can have a far more significant effect on your taxes than you would experience by simply entering into a new marginal tax bracket. Every year I find instances where the effective tax rate on a client’s marginal income is 80% or more, due to the compounding effects of phase-outs.

![]() Example I have prepared the tax return for Maggie and her husband for several years. Each year things are pretty much the same—a little W-2 income, a side business, and a rental. Each year they have about the same income and receive a similar refund. However, this year was different. While their income did not really change, their tax bill shot up by nearly $6,000! I was really surprised (as were they), until I looked into the details. What I found was that they had crossed a particularly important (and unpleasant) phase-out limit. Their rental income had increased only a little (about $1,000), but that increase pushed their allowable rental income $854 over the phase-out limit for the Earned Income Credit. That $854 cost them an additional $5,751 in taxes because of the lost credit. In essence they were being charged a 673% tax on the $854! This is a real-life example of the dramatic effects that fixed-dollar phase-out limits can have on the tax liabilities of individuals.

Example I have prepared the tax return for Maggie and her husband for several years. Each year things are pretty much the same—a little W-2 income, a side business, and a rental. Each year they have about the same income and receive a similar refund. However, this year was different. While their income did not really change, their tax bill shot up by nearly $6,000! I was really surprised (as were they), until I looked into the details. What I found was that they had crossed a particularly important (and unpleasant) phase-out limit. Their rental income had increased only a little (about $1,000), but that increase pushed their allowable rental income $854 over the phase-out limit for the Earned Income Credit. That $854 cost them an additional $5,751 in taxes because of the lost credit. In essence they were being charged a 673% tax on the $854! This is a real-life example of the dramatic effects that fixed-dollar phase-out limits can have on the tax liabilities of individuals.

As you can see, being caught unaware of the phase-outs that affect you can really hurt. Had Maggie and her husband engaged in tax planning with me during the year they could have forgone the extra income and saved a great deal of money in the process, not to mention having a happier renter (by receiving lower rents or nice improvements). Phase-outs are ever looming and you must be actively aware of them to fend off the damage that they could inflict.

It is important to understand that phase-outs affect people at nearly all income levels, not just those who have a high income. In fact, at times they can have their most dramatic effect on low-income individuals.

![]() Example Becky’s husband, Mike, died at an early age, leaving her to care for their daughter on her own. Becky receives Social Security survivor benefits of $18,000 per year, but must supplement that income with other work to pay the bills. Last year her income from employment came to $25,000, giving her a total of $43,000. In an effort to get into a better financial position, Becky found a way to do some extra work from home this year, earning an additional $3,000. However, because Becky’s income fell within the ranges of two phase-outs (Social Security taxation and Earned Income Credit), she will not be able to keep very much of that additional $3,000. In fact, even though she is in the 15% marginal tax bracket, the phase-outs actually create an effective tax of 58% on that additional income. Once you also account for payroll taxes on that income, Becky will actually keep only 44% of the $3,000, or $1,320!

Example Becky’s husband, Mike, died at an early age, leaving her to care for their daughter on her own. Becky receives Social Security survivor benefits of $18,000 per year, but must supplement that income with other work to pay the bills. Last year her income from employment came to $25,000, giving her a total of $43,000. In an effort to get into a better financial position, Becky found a way to do some extra work from home this year, earning an additional $3,000. However, because Becky’s income fell within the ranges of two phase-outs (Social Security taxation and Earned Income Credit), she will not be able to keep very much of that additional $3,000. In fact, even though she is in the 15% marginal tax bracket, the phase-outs actually create an effective tax of 58% on that additional income. Once you also account for payroll taxes on that income, Becky will actually keep only 44% of the $3,000, or $1,320!

This same scenario plays out again and again throughout the tax code. Phase-outs can begin negatively affecting a taxpayer with an income as low as $8,000, and will continue to wreak havoc on his or her income all the way up to $450,000. Littered throughout that range of income are numerous opportunities for the tax code to extract extremely high effective rates of tax on additional income—much higher than the tax brackets would lead you to believe. While the phase-outs are intended to reduce the tax benefits available to the rich, they actually extract their greatest toll on the poor and middle class who are trying to break out of their current financial status.

Making this worse still, these phase-outs often take effect on taxpayers at the same time as their marginal tax rates have increased, giving a solid one–two punch. So, not only do they lose the benefits of their deductions and credits, but they are also paying a higher marginal tax rate on their income. It is not uncommon for me to see a person’s effective marginal tax rates be 80% or greater as he or she crosses over the thresholds of these phase-outs.

Turn It on Its Head

We need to significantly change and simplify the tax code in order to fully overcome these obstacles. However, the only power that most of us have to bring a complete restructuring to pass is through our educated vote. In the meantime, there are still things that you can do to make the best of the situation that we’ve be given.

Understanding how these three factors work together to keep people down is the key to knowing how to overcome them. The wealthy don’t pay very much in taxes (relative to their wealth and income) because they understand these three factors well, and have adjusted their incomes accordingly. They have shifted their income sources to those that are taxed at lower rates or are not taxed at all. They have also adjusted their income needs downward so that their taxable income for the year does not put them into higher tax brackets or subject them to phase-outs.

As you build your wealth you can do the same things, in order for that wealth to accumulate more quickly. Be vigilantly aware of the phase-outs that go into effect in the range of income that is near your current AGI. Use that to your advantage as you work to time your income and deductions in a way that will keep you from being affected by those phase-outs. Also, be aware of the income brackets and how close you are to crossing into a higher (or lower) bracket. Finally, as quickly as you can, begin shifting your sources of income to those that are subject to lower or no taxation.

As you come to understand these factors it will be more clear to you how and when to implement the strategies that are contained in the remainder of this book. You will be able to effectively plan and structure your financial life in such a way as to take maximum advantage of the tax code, helping you build wealth instead of giving it up to the IRS.